Tacrolimus Inhibits Human Tenon’s Fibroblast Migration, Proliferation, and Transdifferentiation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. HTF Cell Culture

2.2. WST-1 Cell Viability and Proliferation Assay System

2.3. Experiment Procedures

2.4. Scratch-Induced Directional Wounding (Migration) Assay

2.5. Western Blot for Cell Proliferation and Transdifferentiation

2.6. Western Blot Assay

2.7. Relevance to the TGF-β Pathway

2.8. Statistics Analysis

3. Results

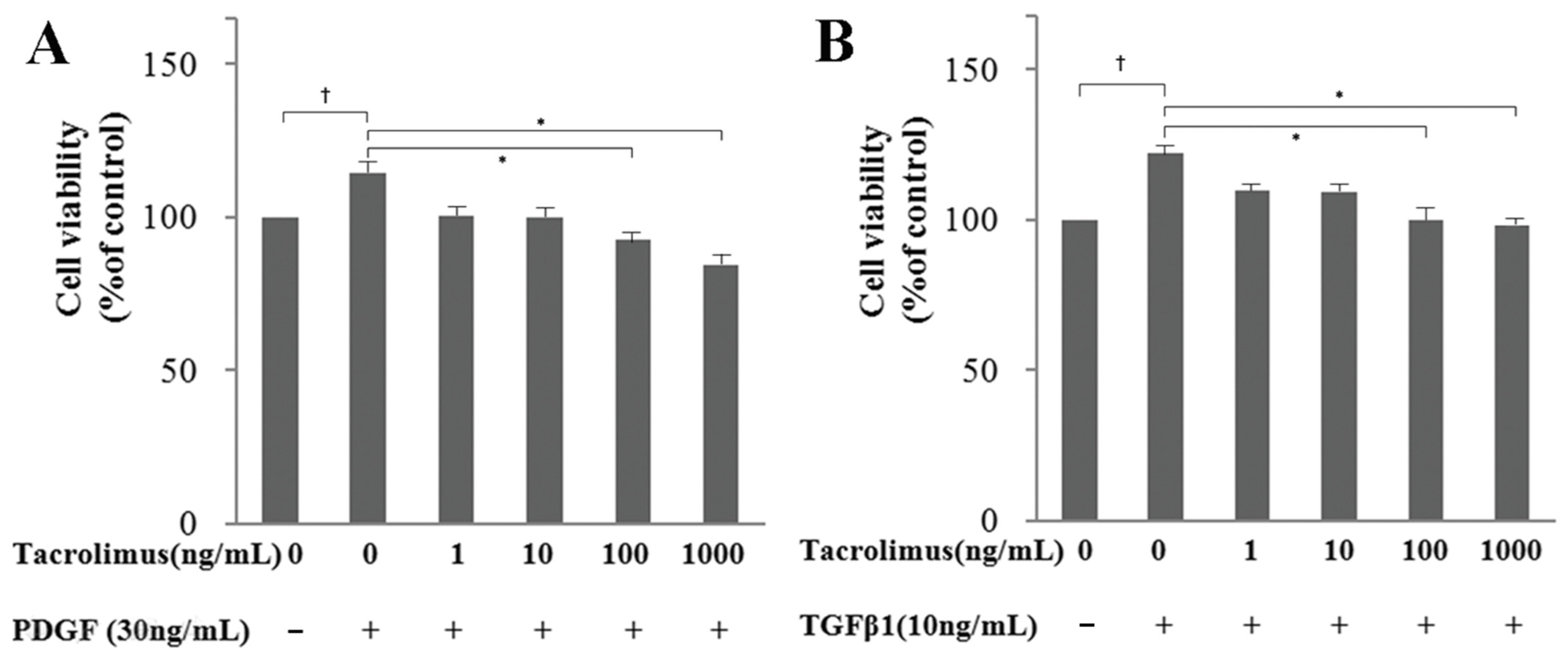

3.1. WST-1 Assay: Cell Viability and Proliferation

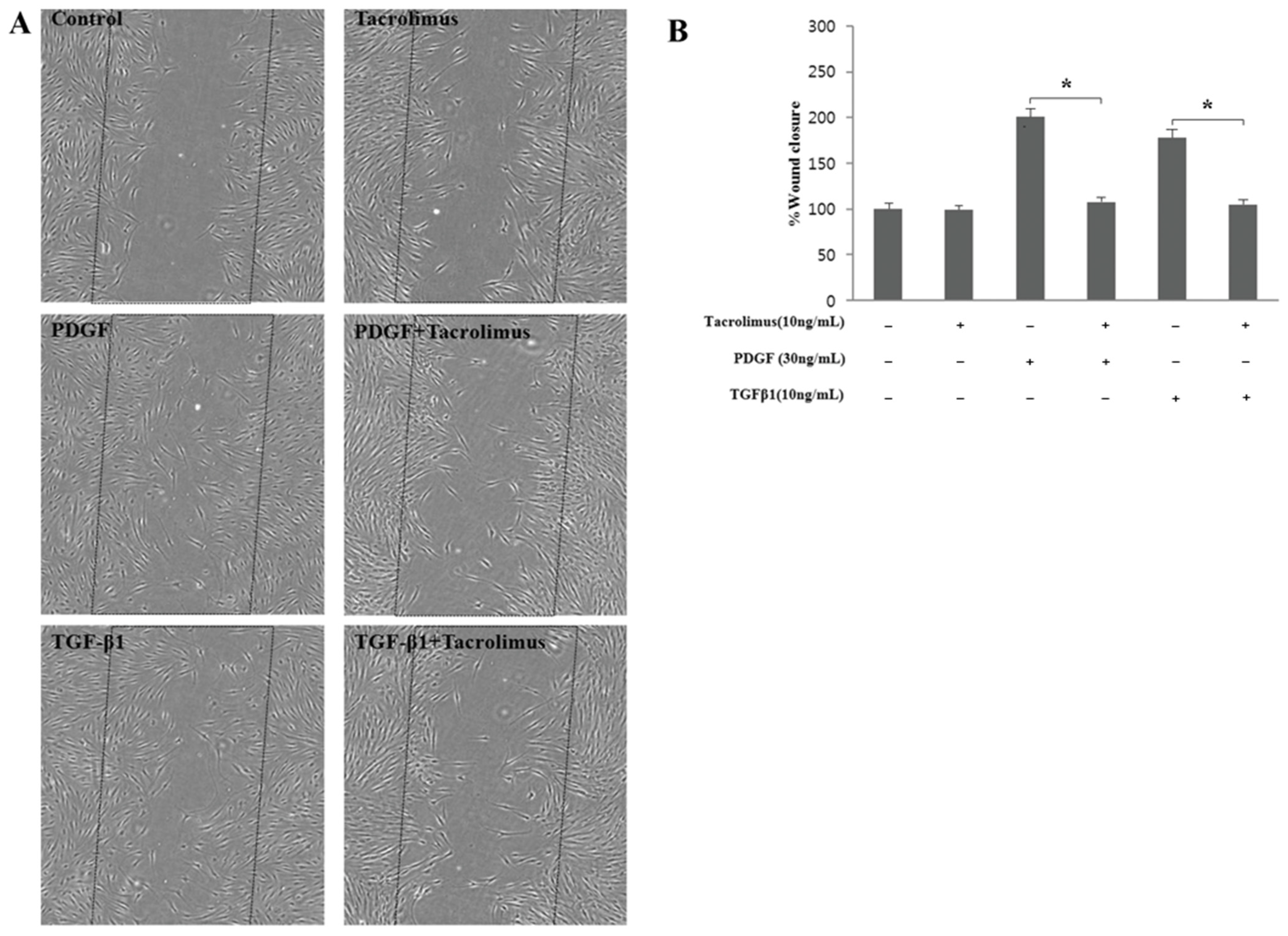

3.2. Cell Migration

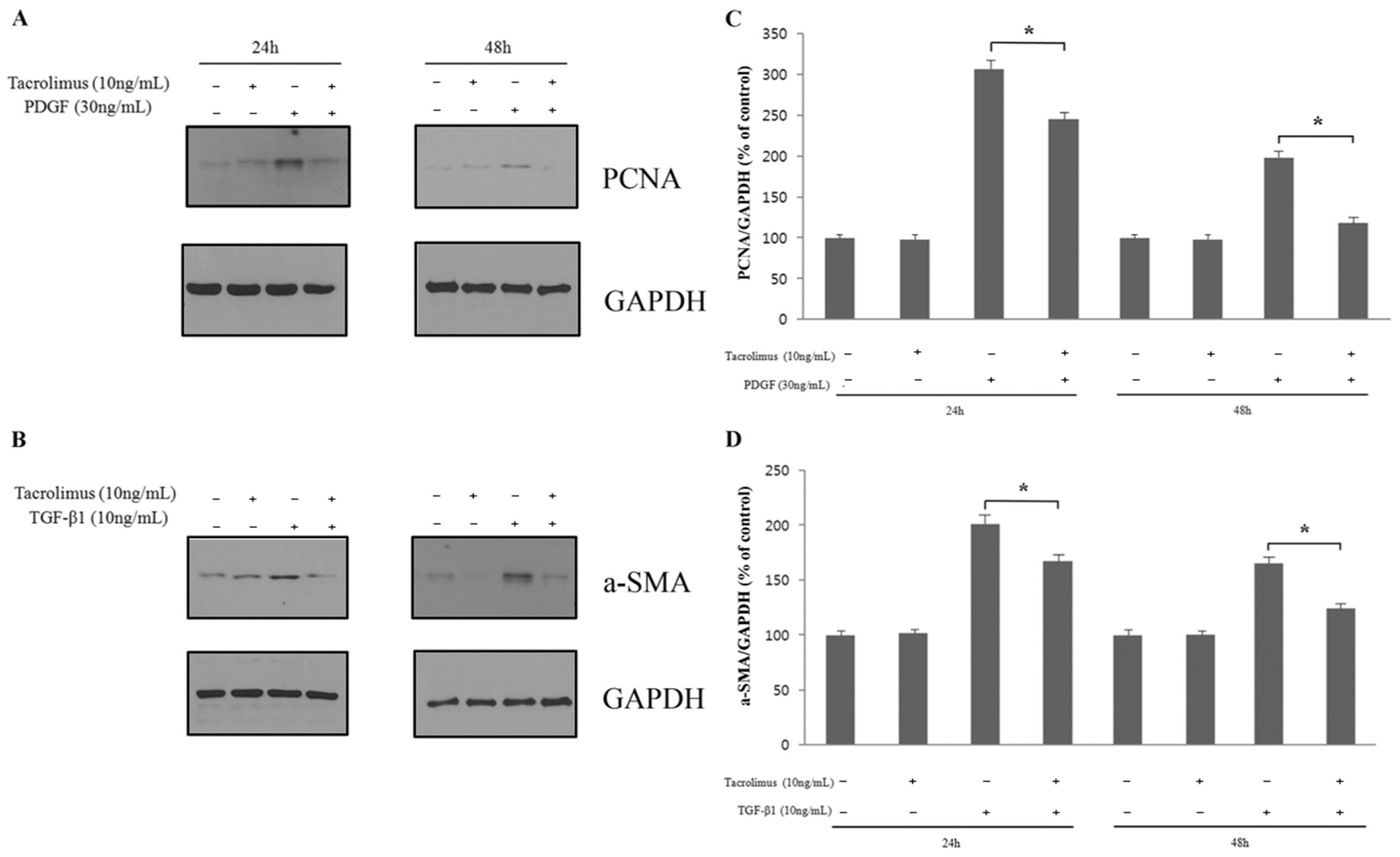

3.3. Cell Proliferation and Transdifferentiation

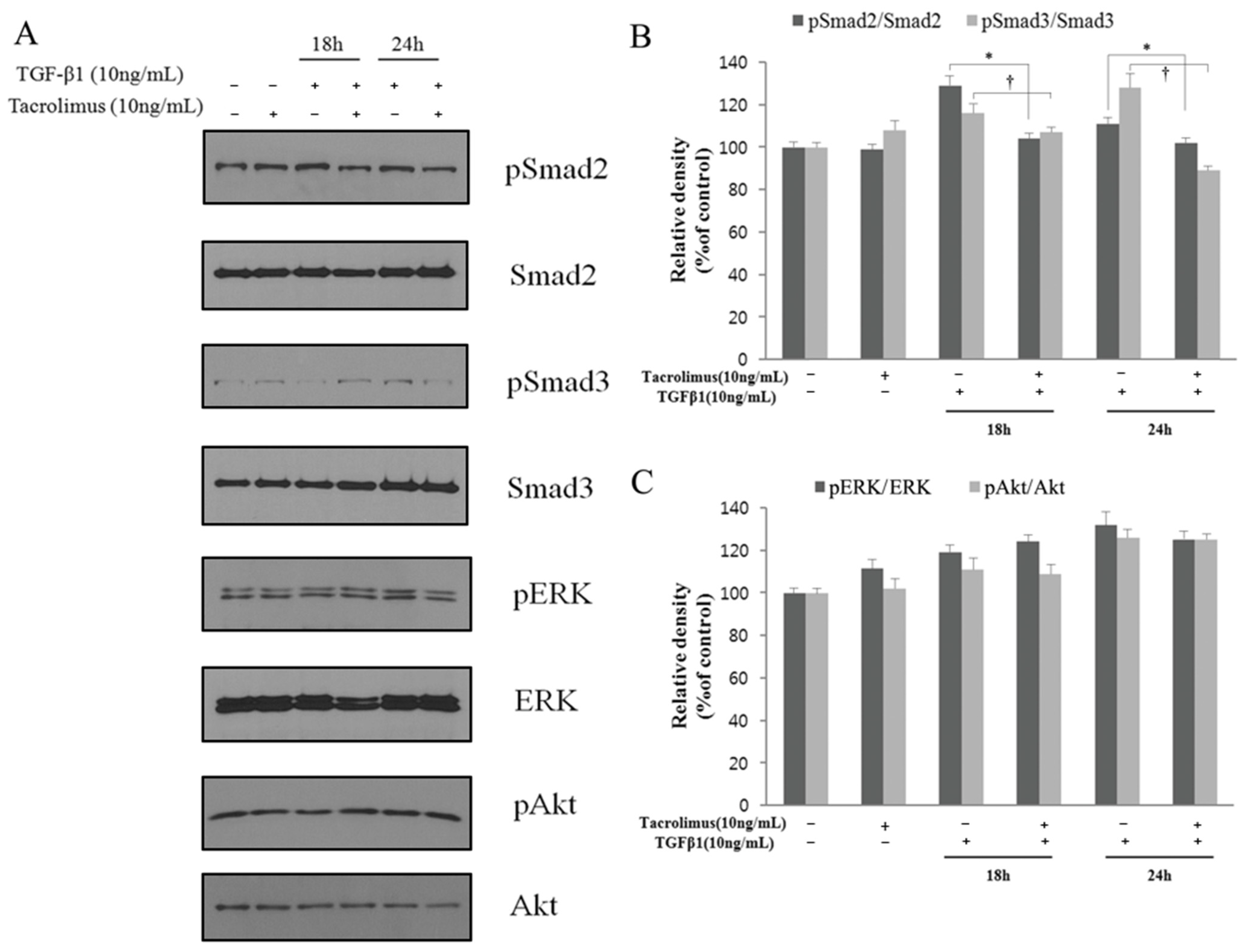

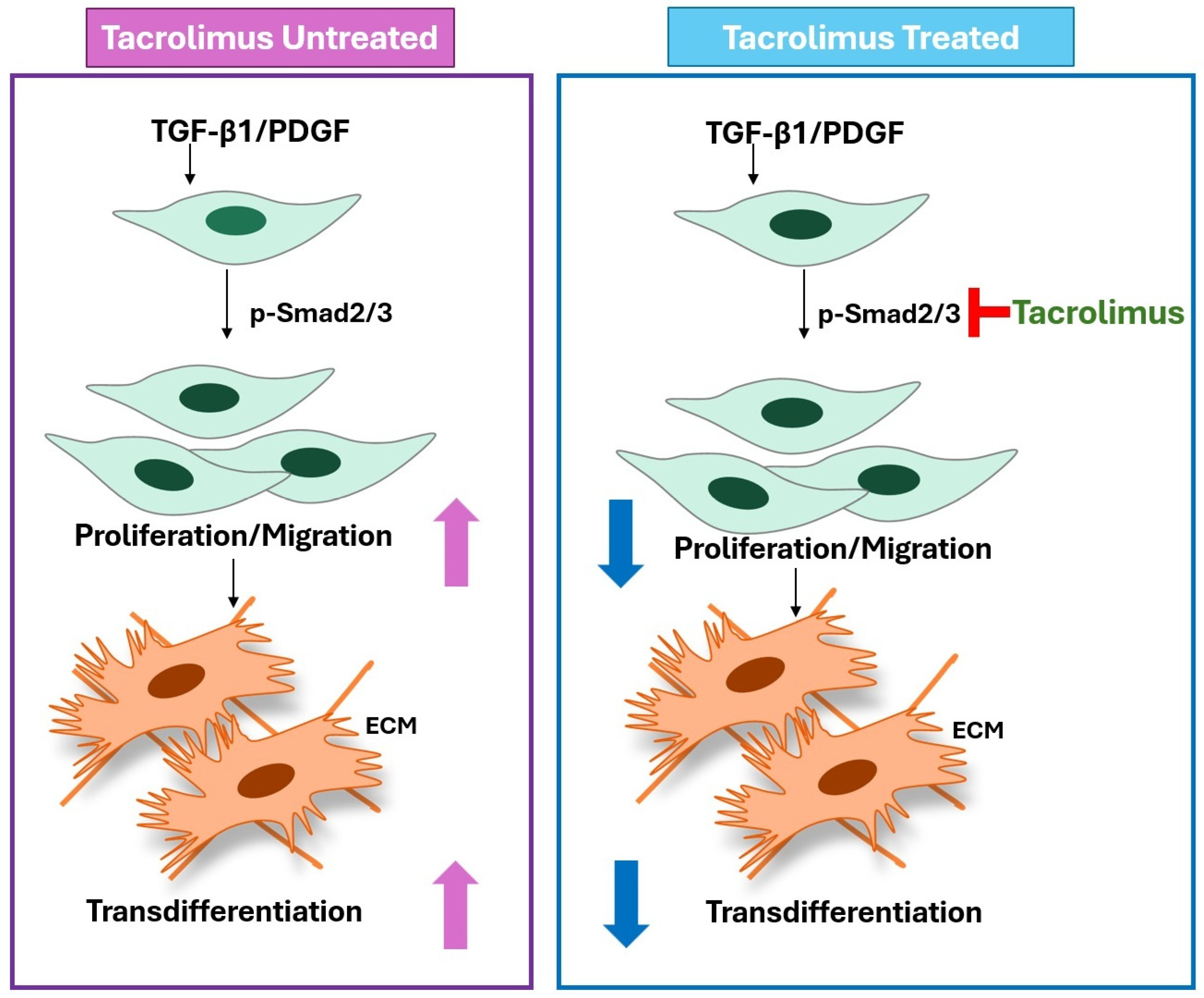

3.4. Relevance to TGF-β Signaling Transduction Pathway

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Francis, B.A.; Du, L.T.; Najafi, K.; Murthy, R.; Kurumety, U.; Rao, N.; Minckler, D.S. Histopathologic features of conjunctival filtering blebs. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2005, 123, 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fuller, J.R.; Bevin, T.H.; Molteno, A.C.; Vote, B.J.; Herbison, P. Anti-inflammatory fibrosis suppression in threatened trabeculectomy bleb failure produces good long term control of intraocular pressure without risk of sight threatening complications. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2002, 86, 1352–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas-Prato, M.; Assalian, A.; Mehdi, A.Z.; Duperré, J.; Thompson, P.; Brazeau, P. Inhibition by rapamycin of PDGF- and bFGF-induced human tenon fibroblast proliferation in vitro. J. Glaucoma 1996, 5, 54–59. [Google Scholar]

- Campos, M.; Takahashi, R.; Tanaka, H.; Chamon, W.; Allemann, N. Inflammation-related scarring after photorefractive keratectomy. Cornea 1998, 17, 607–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, I.C.; Lee, S.M.; Hwang, D.G. Late-onset corneal haze and myopic regression after photorefractive keratectomy (PRK). Cornea 2004, 23, 350–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porges, Y.; Ben-Haim, O.; Hirsh, A.; Levinger, S. Phototherapeutic keratectomy with mitomycin C for corneal haze following photorefractive keratectomy for myopia. J. Refract. Surg. 2003, 19, 40–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fourman, S. Scleritis after glaucoma filtering surgery with mitomycin C. Ophthalmology 1995, 102, 1569–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oram, O.; Gross, R.L.; Wilhelmus, K.R.; Hoover, J.A. Necrotizing keratitis following trabeculectomy with mitomycin. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1995, 113, 19–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, S.W. Early corneal edema following topical application of mitomycin-C. J. Cataract. Refract. Surg. 2004, 30, 1742–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, L.; Jing, W.; Young, A.L. Sodium hyaluronate gel as mitomycin C vehicle to reduce potential endothelial toxicity in pterygium surgery. Cornea 2011, 30, 1286–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.R.; Gregório, E.A. Mitomycin C toxicity in rabbit corneal endothelium. Arq. Bras. Oftalmol. 2009, 72, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, K.; Suh, W.; Kee, C. Comparative study of encapsulated blebs following Ahmed glaucoma valve implantation and trabeculectomy with mitomycin-C. Korean J. Ophthalmol. 2012, 26, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memarzadeh, F.; Varma, R.; Lin, L.T.; Parikh, J.G.; Dustin, L.; Alcaraz, A.; Eliott, D. Postoperative use of bevacizumab as an antifibrotic agent in glaucoma filtration surgery in the rabbit. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2009, 50, 3233–3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Neill, E.C.; Qin, Q.; Van Bergen, N.J.; Connell, P.P.; Vasudevan, S.; Coote, M.A.; Trounce, I.A.; Wong, T.T.; Crowston, J.G. Antifibrotic activity of bevacizumab on human Tenon’s fibroblasts in vitro. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2010, 51, 6524–6532. [Google Scholar]

- Greaves, N.S.; Ashcroft, K.J.; Baguneid, M.; Bayat, A. Current understanding of molecular and cellular mechanisms in fibroplasia and angiogenesis during acute wound healing. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2013, 72, 206–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahdavian Delavary, B.; van der Veer, W.M.; van Egmond, M.; Niessen, F.B.; Beelen, R.H. Macrophages in skin injury and repair. Immunobiology 2011, 216, 753–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werner, S.; Grose, R. Regulation of wound healing by growth factors and cytokines. Physiol. Rev. 2003, 83, 835–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, S.; Clipstone, N.; Timmermann, L.; Northrop, J.; Graef, I.; Fiorentino, D.; Nourse, J.; Crabtree, G.R. The mechanism of action of cyclosporin A and FK506. Clin. Immunol. Immunopathol. 1996, 80, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siekierka, J.J. Probing T-cell signal transduction pathways with the immunosuppressive drugs, FK-506 and rapamycin. Immunol. Res. 1994, 13, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, M.; Montezano, A.C.; Touyz, R.M. Angiotensin II signalling and calcineurin in cardiac fibroblasts: Differential effects of calcineurin inhibitors FK506 and cyclosporine A. Ther. Adv. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2012, 6, 5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Adachi, T.; Fukuda, K.; Kondo, Y.; Nishida, T. Inhibition by tranilast of the cytokine-induced expression of chemokines and the adhesion molecule VCAM-1 in human corneal fibroblasts. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2010, 51, 3954–3960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sieb, J.P. Myasthenia gravis: An update for the clinician. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2014, 175, 408–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagi, Y.; Sanjo, N.; Yokota, T.; Mizusawa, H. Tacrolimus monotherapy: A promising option for ocular myasthenia gravis. Eur. Neurol. 2013, 69, 344–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.J.; Kim, S.W.; Seo, K.Y. Application for tacrolimus ointment in treating refractory inflammatory ocular surface diseases. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2013, 155, 804–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rikkers, S.M.; Holland, G.N.; Drayton, G.E.; Michel, F.K.; Torres, M.F.; Takahashi, S. Topical tacrolimus treatment of atopic eyelid disease. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2003, 135, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryu, E.H.; Kim, J.M.; Laddha, P.M.; Chung, E.S.; Chung, T.Y. Therapeutic effect of 0.03% tacrolimus ointment for ocular graft versus host disease and vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Korean J. Ophthalmol. 2012, 26, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, G.; Tzamalis, A.; Tsinopoulosm, I.; Ziakas, N. Topical Use of Tacrolimus in Corneal and Ocular Surface Pathologies: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 5347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trelford, C.B.; Denstedt, J.T.; Armstrong, J.J.; Hutnik, C.M.L. The Pro-Fibrotic Behavior of Human Tenon’s Capsule Fibroblasts in Medically Treated Glaucoma Patients. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2020, 14, 1391–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, J.; Cassidy, H.; Slattery, C.; Ryan, M.P.; McMorrow, T. Tacrolimus Modulates TGF-β Signaling to Induce Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Human Renal Proximal Tubule Epithelial Cells. J. Clin. Med. 2016, 5, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, S.Y.; Kim, E.-S.; Han, G.S.; Suh, L.H.; Jung, H.S.; Tchah, H.; Kim, J.Y. Safety and efficacy of tacrolimus-coated silicone plates as an alternative to mitomycin C in a rabbit model of conjunctival fibrosis. PLoS ONE 2019, 5, e0219194. [Google Scholar]

- Erdinest, N.; Ben-Eli, H.; Solomon, A. Topical tacrolimus for allergic eye diseases. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2019, 19, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.Y.; Liu, H.Y.; Chu, H.S.; Chen, W.L.; Hu, F.R.; Wang, I.J. Dermatologic tacrolimus ointment on the eyelids for steroid-refractory vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Graefe’s Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2019, 257, 967–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyazaki, D.; Fukushima, A.; Ohashi, Y.; Ebihara, N.; Uchio, E.; Okamoto, S.; Shoji, J.; Takamura, E.; Nakagawa, Y.; Namba, K.; et al. Steroid-Sparing Effect of 0.1% Tacrolimus Eye Drop for Treatment of Shield Ulcer and Corneal Epitheliopathy in Refractory Allergic Ocular Diseases. Ophthalmology 2017, 124, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoji, J.; Ohashi, Y.; Fukushima, A.; Miyazaki, D.; Uchio, E.; Takamura, E.; Fujishima, H.; Namba, K.; Kumagai, N.; Ebihara, N.; et al. Topical Tacrolimus for Chronic Allergic Conjunctival Disease with and without Atopic Dermatitis. Curr. Eye Res. 2019, 44, 796–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquezan, M.C.; Nascimento, H.; Vieira, L.A.; Serapião, M.; Ghanem, R.C.; Belfort, R., Jr.; Freitas, D. Effect of Topical Tacrolimus in the Treatment of Thygeson’s Superficial Punctate Keratitis. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2015, 160, 663–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoughy, S.S.; Tabbara, K.F. Topical Tacrolimus in Thygeson Superficial Punctate Keratitis. Cornea 2020, 39, 742–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffari, R.; Ghassemi, H.; Zarei-Ghanavati, M.; Latifi, G.; Dehghani, S.; Haq, Z.; Djalilian, A.R. Tacrolimus Eye Drops as Adjunct Therapy in Severe Corneal Endothelial Rejection Refractory to Corticosteroids. Cornea 2017, 36, 1195–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakassegawa-Naves, F.E.; Ricci, H.M.M.; Moscovici, B.K.; Miyamoto, D.A.; Chiacchio, B.B.; Holzchuh, R.; Santo, R.M.; Hida, R.Y. Tacrolimus Ointment for Refractory Posterior Blepharitis. Curr. Eye Res. 2017, 42, 1440–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, F.; Westcott, M.; Rees, A.; Robson, A.G.; Kapoor, B.; Holder, G.; Pavesio, C. Safety profile and efficacy of tacrolimus in the treatment of birdshot retinochoroiditis: A retrospective case series review. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2018, 102, 983–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, M.C.; Fialho, S.L.; Souza, P.A.; Fulgêncio, G.O.; Da Silva, G.R.; Silva-Cunha, A. Tacrolimus-loaded PLGA implants: In vivo release and ocular toxicity. Curr. Eye Res. 2014, 39, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahiner, N.; Kravitz, D.J.; Qadir, R.; Blake, D.A.; Haque, S.; John, V.T.; Margo, C.E.; Ayyala, R.S. Creation of a drug-coated glaucoma drainage device using polymer technology: In vitro and in vivo studies. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2009, 127, 448–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Yoon, C.H.; Kim, M.K.; Oh, J.Y. Topical Tacrolimus 0.03% for Maintenance Therapy in Steroid-Dependent, Recurrent Phlyctenular Keratoconjunctivitis. Cornea 2018, 37, 168–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.-C.; Wang, T.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.-L.; Zhao, R.-Y.; Tan, W. Tacrolimus inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis by decreasing survivin in scar fibroblasts after glaucoma surgery. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2018, 22, 2934–2940. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, C.S.; Viveiros, M.M.; Schellini, S.A.; Candeias, J.M.; Padovani, C.R. Fibroblasts from recurrent pterygium and normal Tenon’s capsule exposed to tacrolimus (FK-506). Arq. Bras. Oftalmol. 2007, 70, 235–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derynck, R.; Muthusamy, B.P.; Saeteurn, K.Y. Signaling pathway cooperation in TGF-beta-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2014, 31, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustakas, A.; Heldin, P. TGFbeta and matrix-regulated epithelial to mesenchymal transition. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1840, 2621–2634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varga, J.; Pasche, B. Transforming growth factor beta as a therapeutic target in systemic sclerosis. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2009, 5, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gijsen, V.M.; Hesselink, D.A.; Croes, K.; Koren, G.; de Wildt, S.N. Prevalence of renal dysfunction in tacrolimus-treated pediatric transplant recipients: A systematic review. Pediatr. Transplant. 2013, 17, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rebibo, L.; Tam, C.; Sun, Y.; Shoshani, E.; Badihi, A.; Nassar, T.; Benita, S. Topical tacrolimus nanocapsules eye drops for therapeutic effect enhancement in both anterior and posterior ocular inflammation models. J. Control. Release 2021, 10, 283–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunet, M.; van Gelder, T.; Åsberg, A.; Haufroid, V.; Hesselink, D.A.; Langman, L.; Lemaitre, F.; Marquet, P.; Seger, C.; Shipkova, M.; et al. Therapeutic Drug Monitoring of Tacrolimus-Personalized Therapy: Second Consensus Report. Ther. Drug Monit. 2019, 41, 261–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massoglia, G.; Ramnarine, M.; Schuh, M.J. Tacrolimus Therapeutic Drug Monitoring in Kidney Transplant Patients Before and After Pharmacist Post-transplant Consults. Innov. Pharm. 2021, 12, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hur, W.; Park, J.; Lee, J.-H.; Chung, H.-S.; Shin, J.-A.; Lee, H.; Tchah, H.; Kim, J.-Y. Tacrolimus Inhibits Human Tenon’s Fibroblast Migration, Proliferation, and Transdifferentiation. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2956. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122956

Hur W, Park J, Lee J-H, Chung H-S, Shin J-A, Lee H, Tchah H, Kim J-Y. Tacrolimus Inhibits Human Tenon’s Fibroblast Migration, Proliferation, and Transdifferentiation. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(12):2956. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122956

Chicago/Turabian StyleHur, Woojune, Jeongeun Park, Jae-Hyuck Lee, Ho-Seok Chung, Jin-A Shin, Hun Lee, Hungwon Tchah, and Jae-Yong Kim. 2025. "Tacrolimus Inhibits Human Tenon’s Fibroblast Migration, Proliferation, and Transdifferentiation" Biomedicines 13, no. 12: 2956. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122956

APA StyleHur, W., Park, J., Lee, J.-H., Chung, H.-S., Shin, J.-A., Lee, H., Tchah, H., & Kim, J.-Y. (2025). Tacrolimus Inhibits Human Tenon’s Fibroblast Migration, Proliferation, and Transdifferentiation. Biomedicines, 13(12), 2956. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122956