Antibody-Mediated In Vitro Activation and Expansion of Blood Donor-Derived Natural Killer Cells with Transient Anti-Tumor Efficacy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cells and Animals

2.2. Isolation and Expansion of NK Cells

2.3. Flow Cytometry

2.4. Luc-Based Cytotoxicity Assays

2.5. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

2.6. Animal Grouping and Intervention

2.7. RNA Sequencing

2.8. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Anti-CD16 and Anti-CD137 Antibodies Induce Robust Activation and Expansion of Donor-Derived Human PBMCs

3.2. Elevated Expression of Activating and Inhibitory Receptors in SNK Cells

3.3. SNK Cells Exhibited Enhanced Cytotoxicity and Effector Molecule Secretion In Vitro

3.4. SNK Cells Demonstrated Enhanced Anti-Tumor Efficacy In Vivo

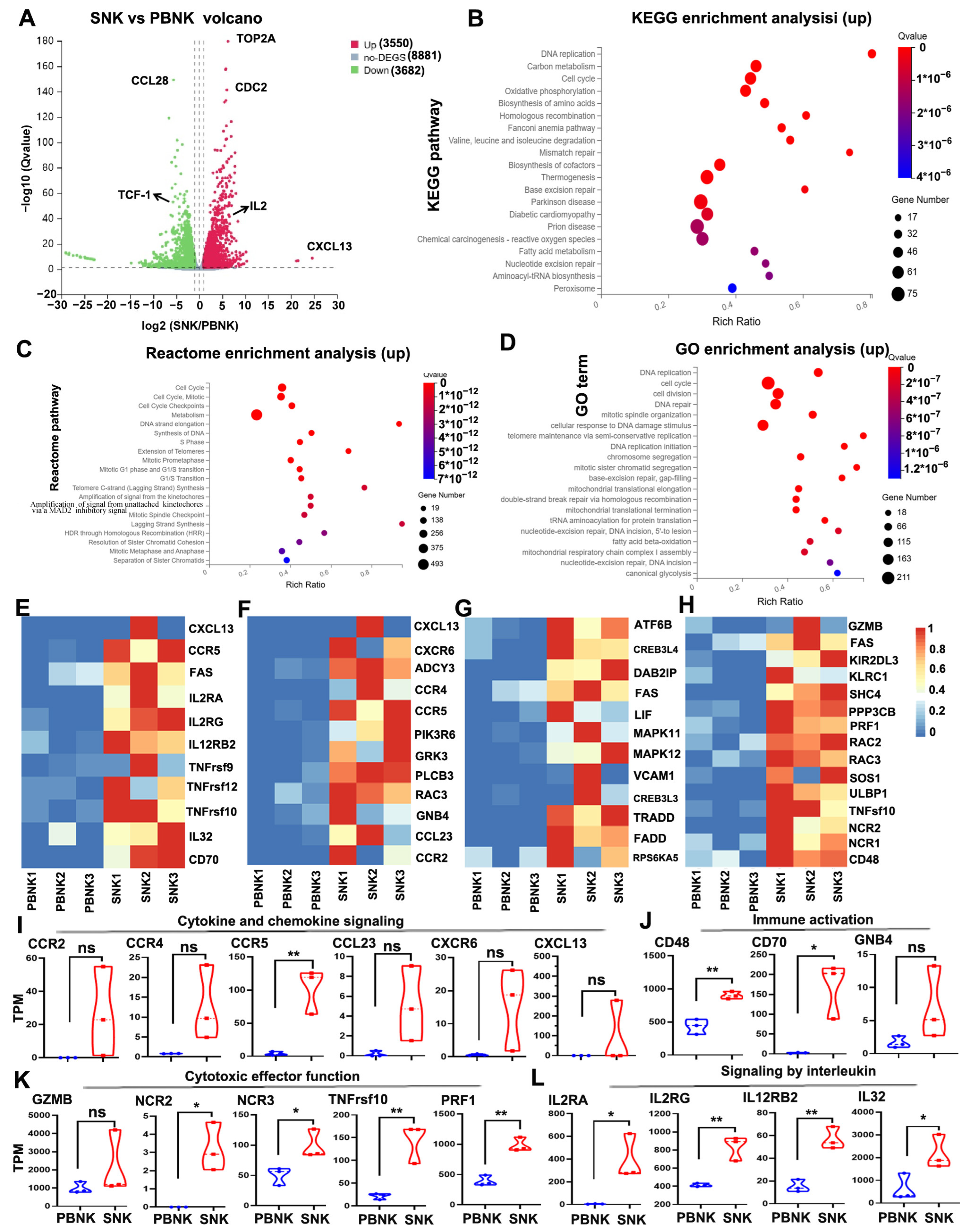

3.5. Enhanced Cytokine Signaling and Immune Activation Signatures in SNK Cells

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Becker, P.S.A.; Suck, G.; Nowakowska, P.; Ullrich, E.; Seifried, E.; Bader, P.; Tonn, T.; Seidl, C. Selection and expansion of natural killer cells for NK cell-based immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2016, 65, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Z.; Wu, S.; Zhang, Z.; Ding, S. Mechanism of tumor cells escaping from immune surveillance of NK cells. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 2020, 42, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, K.; Hu, S.; Mei, X.; Cheng, M. Innate Immune Cells in the Esophageal Tumor Microenvironment. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 654731, Erratum in Front Immunol. 2021, 12, 708705. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.708705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- André, P.; Denis, C.; Soulas, C.; Bourbon-Caillet, C.; Lopez, J.; Arnoux, T.; Bléry, M.; Bonnafous, C.; Gauthier, L.; Morel, A.; et al. Anti-NKG2A mAb Is a Checkpoint Inhibitor that Promotes Anti-tumor Immunity by Unleashing Both T and NK Cells. Cell 2018, 175, 1731–1743.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhou, L.; Gu, L.; Gu, Y.; Chen, L.; Lian, Y.; Huang, Y. Veritable antiviral capacity of natural killer cells in chronic HBV infection: An argument for an earlier anti-virus treatment. J. Transl. Med. 2017, 15, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamers-Kok, N.; Panella, D.; Georgoudaki, A.-M.; Liu, H.; Özkazanc, D.; Kučerová, L.; Duru, A.D.; Spanholtz, J.; Raimo, M. Natural killer cells in clinical development as non-engineered, engineered, and combination therapies. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2022, 15, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieto, Y.; Banerjee, P.; Kaur, I.; Basar, R.; Li, Y.; Daher, M.; Rafei, H.; Kerbauy, L.N.; Kaplan, M.; Marin, D.; et al. Allogeneic NK cells with a bispecific innate cell engager in refractory relapsed lymphoma: A phase 1 trial. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 1987–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heipertz, E.L.; Zynda, E.R.; Stav-Noraas, T.E.; Hungler, A.D.; Boucher, S.E.; Kaur, N.; Vemuri, M.C. Current Perspectives on “Off-The-Shelf” Allogeneic NK and CAR-NK Cell Therapies. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 732135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, S.; De Angelis, B.; Del Bufalo, F.; Ciccone, R.; Donsante, S.; Volpe, G.; Manni, S.; Guercio, M.; Pezzella, M.; Iaffaldano, L.; et al. Safe and effective off-the-shelf immunotherapy based on CAR.CD123-NK cells for the treatment of acute myeloid leukaemia. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2022, 15, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velasco-de-Andrés, M.; Català, C.; Carrillo-Serradell, L.; Planells-Romeo, V.; Aragón-Serrano, L.; Español-Rego, M.; Pérez-Amill, L.; Puerta-Alcalde, P.; García-Vidal, C.; Juan, M.; et al. Adoptive transfer of NK cells engineered with a CD5-based chimeric antigen receptor (SRCD5CAR) to treat invasive fungal infections. Mol. Ther. 2025, 33, 5442–5452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teng, K.Y.; Mansour, A.G.; Zhu, Z.; Li, Z.; Tian, L.; Ma, S.; Xu, B.; Lu, T.; Chen, H.; Hou, D.; et al. Off-the-Shelf Prostate Stem Cell Antigen-Directed Chimeric Antigen Receptor Natural Killer Cell Therapy to Treat Pancreatic Cancer. Gastroenterology 2022, 162, 1319–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Hu, M.; Wang, H.; Lu, S.; Li, Z.; Dilimulati, D.; Jiao, S.; Lu, S.; et al. Sufficiently activated mature natural killer cells derived from peripheral blood mononuclear cells substantially enhance antitumor activity. Immun. Inflamm. Dis. 2024, 12, e1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang, Q.; Yu, X.; Xu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Han, T.; Zhang, Y.; Lv, M.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xu, L.; et al. Expanded clinical-grade NK cells exhibit stronger effects than primary NK cells against HCMV infection. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2023, 20, 895–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prager, I.; Watzl, C. Mechanisms of natural killer cell-mediated cellular cytotoxicity. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2019, 105, 1319–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez-Silerio, G.Y.; Bueno-Topete, M.R.; Vega-Magaña, A.N.; Bastidas-Ramirez, B.E.; Gutierrez-Franco, J.; Escarra-Senmarti, M.; Pedraza-Brindis, E.J.; Peña-Rodriguez, M.; Ramos-Marquez, M.E.; Delgado-Rizo, V.; et al. Non-fitness status of peripheral NK cells defined by decreased NKp30 and perforin, and increased soluble B7H6, in cervical cancer patients. Immunology 2023, 168, 538–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Cen, D.; Gan, H.; Sun, Y.; Huang, N.; Xiong, H.; Jin, Q.; Su, L.; Liu, X.; Wang, K.; et al. Adoptive Transfer of NKG2D CAR mRNA-Engineered Natural Killer Cells in Colorectal Cancer Patients. Mol. Ther. 2019, 27, 1114–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oth, T.; Habets, T.H.P.M.; Germeraad, W.T.V.; Zonneveld, M.I.; Bos, G.M.J.; Vanderlocht, J. Pathogen recognition by NK cells amplifies the pro-inflammatory cytokine production of monocyte-derived DC via IFN-γ. BMC Immunol. 2018, 19, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, Q.; Rückert, T.; Romagnani, C. Natural killer cell specificity for viral infections. Nat. Immunol. 2018, 19, 800–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Blum, R.H.; Bernareggi, D.; Ask, E.H.; Wu, Z.; Hoel, H.J.; Meng, Z.; Wu, C.; Guan, K.-L.; Malmberg, K.-J.; et al. Metabolic Reprograming via Deletion of CISH in Human iPSC-Derived NK Cells Promotes In Vivo Persistence and Enhances Anti-tumor Activity. Cell Stem Cell 2020, 27, 224–237.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dotiwala, F.; Mulik, S.; Polidoro, R.B.; Ansara, J.A.; Burleigh, B.A.; Walch, M.; Gazzinelli, R.T.; Lieberman, J. Killer lymphocytes use granulysin, perforin and granzymes to kill intracellular parasites. Nat. Med. 2016, 22, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feehan, D.D.; Jamil, K.; Polyak, M.J.; Ogbomo, H.; Hasell, M.; Li, S.; Xiang, R.F.; Parkins, M.; Trapani, J.A.; Harrison, J.J.; et al. Natural killer cells kill extracellular Pseudomonas aeruginosa using contact-dependent release of granzymes B and H. PLoS Pathog. 2022, 18, e1010325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, M.; Chen, M.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, W.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, X.; Guan, Y.; Liu, J.; Feng, K.; et al. Manganese is critical for antitumor immune responses via cGAS-STING and improves the efficacy of clinical immunotherapy. Cell Res. 2020, 30, 966–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amer, J.; Salhab, A.; Safadi, R. Rosuvastatin restores liver tissue-resident NK cell activation in aged mice by improving mitochondrial function. Biomed Pharmacother. 2025, 186, 118000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gokhale, S.G.; Gokhale, S.S. Transfusion-associated graft versus host disease (TAGVHD)--with reference to neonatal period. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015, 28, 700–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.H.; Lim, E.J.; Kim, S.W.; Moon, Y.W.; Park, K.S.; An, H.-J. IL-27 enhances IL-15/IL-18-mediated activation of human natural killer cells. J. Immunother. Cancer 2019, 7, 168, Erratum in J Immunother. Cancer 2019, 7, 211. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40425-019-0688-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Guo, M.; Huang, M.; Liu, Y.; Qian, Y.; Liu, Q.; Cao, X. Neoleukin-2/15-armored CAR-NK cells sustain superior therapeutic efficacy in solid tumors via c-Myc/NRF1 activation. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Caligiuri, M.A.; Yu, J. Harnessing IL-15 signaling to potentiate NK cell-mediated cancer immunotherapy. Trends Immunol. 2022, 43, 833–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Meng, Y.; Zhang, L.; Han, Z.; Feng, X. High-efficient generation of natural killer cells from peripheral blood with preferable cell vitality and enhanced cytotoxicity by combination of IL-2, IL-15 and IL-18. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2021, 534, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, M.; Jeong, H.; Noh, I.; Park, J. Recent advances in feeder-free NK cell expansion as a future direction of adoptive cell therapy. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1675353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thangaraj, J.L.; Phan, M.T.; Kweon, S.; Kim, J.; Lee, J.-M.; Hwang, I.; Park, J.; Doh, J.; Lee, S.-H.; Vo, M.-C.; et al. Expansion of cytotoxic natural killer cells in multiple myeloma patients using K562 cells expressing OX40 ligand and membrane-bound IL-18 and IL-21. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2022, 71, 613–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandani, B.; Movahedin, M. Learning Towards Maturation of Defined Feeder-free Pluripotency Culture Systems: Lessons from Conventional Feeder-based Systems. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2024, 20, 484–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jo, H.; Jo, Y.; Koh, S.K.; Lee, M.; Kim, J.; Kweon, S.; Park, J.; Kim, H.-Y.; Cho, D. Optimization of Natural Killer Cell Expansion with K562-mbIL-18/-21 Feeder Cells and Assurance of Feeder Cell-free Products. Ann. Lab. Med. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kweon, S.; Phan, M.T.; Chun, S.; Yu, H.; Kim, J.; Kim, S.; Lee, J.; Ali, A.K.; Lee, S.-H.; Kim, S.-K.; et al. Expansion of Human NK Cells Using K562 Cells Expressing OX40 Ligand and Short Exposure to IL-21. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amand, M.; Iserentant, G.; Poli, A.; Sleiman, M.; Fievez, V.; Sanchez, I.P.; Sauvageot, N.; Michel, T.; Aouali, N.; Janji, B.; et al. Human CD56dimCD16dim Cells As an Individualized Natural Killer Cell Subset. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Federicis, D.; Capuano, C.; Ciuti, D.; Molfetta, R.; Galandrini, R.; Palmieri, G. Nutrient transporter pattern in CD56dim NK cells: CD16 (FcγRIIIA)-dependent modulation and association with memory NK cell functional profile. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1477776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidard, L.; Dureuil, C.; Baudhuin, J.; Vescovi, L.; Durand, L.; Sierra, V.; Parmantier, E. CD137 (4-1BB) Engagement Fine-Tunes Synergistic IL-15- and IL-21-Driven NK Cell Proliferation. J. Immunol. 2019, 203, 676–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Luo, S.; Zeng, F.; Deng, Q.; Luo, Y.; Chen, D.; Ren, H.; Xia, W.; Ye, X.; Huang, S.; Li, T.; et al. Antibody-Mediated In Vitro Activation and Expansion of Blood Donor-Derived Natural Killer Cells with Transient Anti-Tumor Efficacy. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2934. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122934

Luo S, Zeng F, Deng Q, Luo Y, Chen D, Ren H, Xia W, Ye X, Huang S, Li T, et al. Antibody-Mediated In Vitro Activation and Expansion of Blood Donor-Derived Natural Killer Cells with Transient Anti-Tumor Efficacy. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(12):2934. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122934

Chicago/Turabian StyleLuo, Shengxue, Feifeng Zeng, Qitao Deng, Yalin Luo, Dawei Chen, Hui Ren, Wenjie Xia, Xin Ye, Shuxin Huang, Tingting Li, and et al. 2025. "Antibody-Mediated In Vitro Activation and Expansion of Blood Donor-Derived Natural Killer Cells with Transient Anti-Tumor Efficacy" Biomedicines 13, no. 12: 2934. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122934

APA StyleLuo, S., Zeng, F., Deng, Q., Luo, Y., Chen, D., Ren, H., Xia, W., Ye, X., Huang, S., Li, T., Fu, Y., Rong, X., & Liang, H. (2025). Antibody-Mediated In Vitro Activation and Expansion of Blood Donor-Derived Natural Killer Cells with Transient Anti-Tumor Efficacy. Biomedicines, 13(12), 2934. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122934