Deconstructing Therapeutic Failure with Inhaled Therapy in Hospitalized Patients: Phenotypes, Risk Profiles, and Clinical Inertia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Study Population and Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Data Collection and Measurement

2.4. Variable Selection and Operational Definitions

- Primary Exposure: The primary exposure was the patient phenotype, which was derived empirically from the data using the unsupervised cluster analysis detailed in Section 2.6.

- Primary Patient-Level Outcome: The main clinical outcome was the presence of at least one device-specific critical error, identified via validated checklists.

- Process-of-Care Outcomes (Clinical Inertia): Three distinct, non-mutually exclusive forms of clinical inertia were defined. These domains were selected a priori to capture the three complementary mechanisms of suboptimal care: behavioral barriers (Device-Level), therapeutic decision-making (Therapeutic Class), and regimen implementation (Adherence-Related).

- (a)

- Device-Level Inertia (DLI): Defined as the failure to change the inhaler device type at discharge for a patient with a documented, device-specific critical inhalation error with their home device. This unbiased, technique-focused definition was used to ensure a methodologically consistent comparison of clinical inertia across all device classes.

- (b)

- Therapeutic Class Inertia (TCI): Defined as the failure to escalate inhaled therapy at discharge for a high-risk patient. High-risk status was determined by evidence of significant healthcare resource utilization in the preceding year (≥1 respiratory-related hospitalization or emergency department visit, or ≥2 courses of systemic antibiotics).

- (c)

- Adherence-Related Inertia (ARI): Defined as the failure to simplify the inhaler regimen (e.g., reducing the number of devices) at discharge for a patient with documented poor adherence, defined as a Test of Adherence to Inhalers (TAI) score < 50.

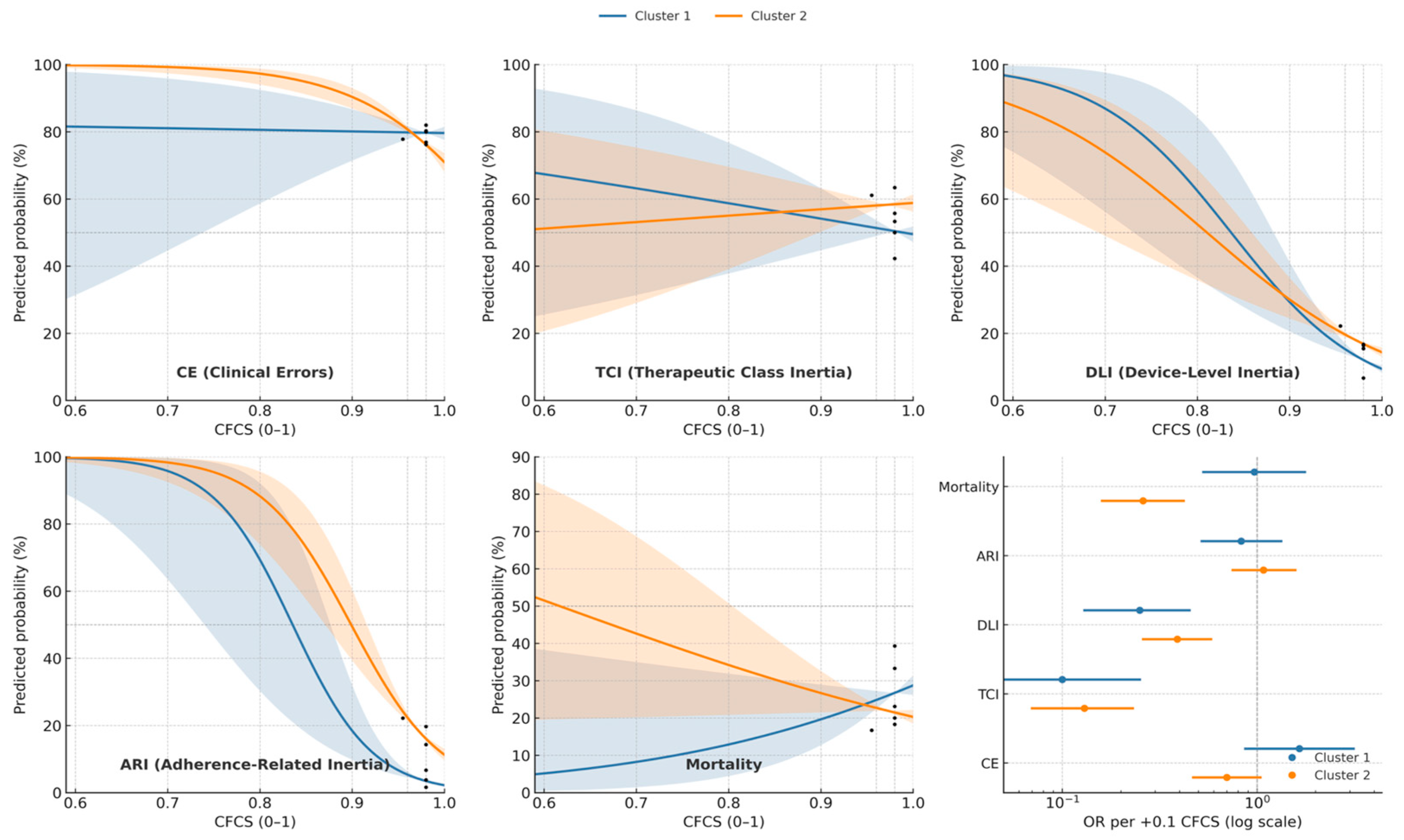

- Composite indicators: Finally, to quantify the patient’s objective capability to use their device, a composite Clinical Frailty and Competence Score (CFCS) was developed a priori. As detailed in the Methodological Analysis—Supplementary Materials File S2 (Section G), this score was constructed by averaging three rescaled domains directly related to inhaler use: (a) peak inspiratory flow, (b) a knowledge composite, and (c) TAI adherence. The score was normalized to a 0–1 scale (higher values = greater capability). The robustness of the CFCS as a predictor was validated through extensive sensitivity analyses (also provided in Supplementary Materials Section G, Table S10).

2.5. Sample Size and Power Considerations

2.6. Statistical Analysis

2.7. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

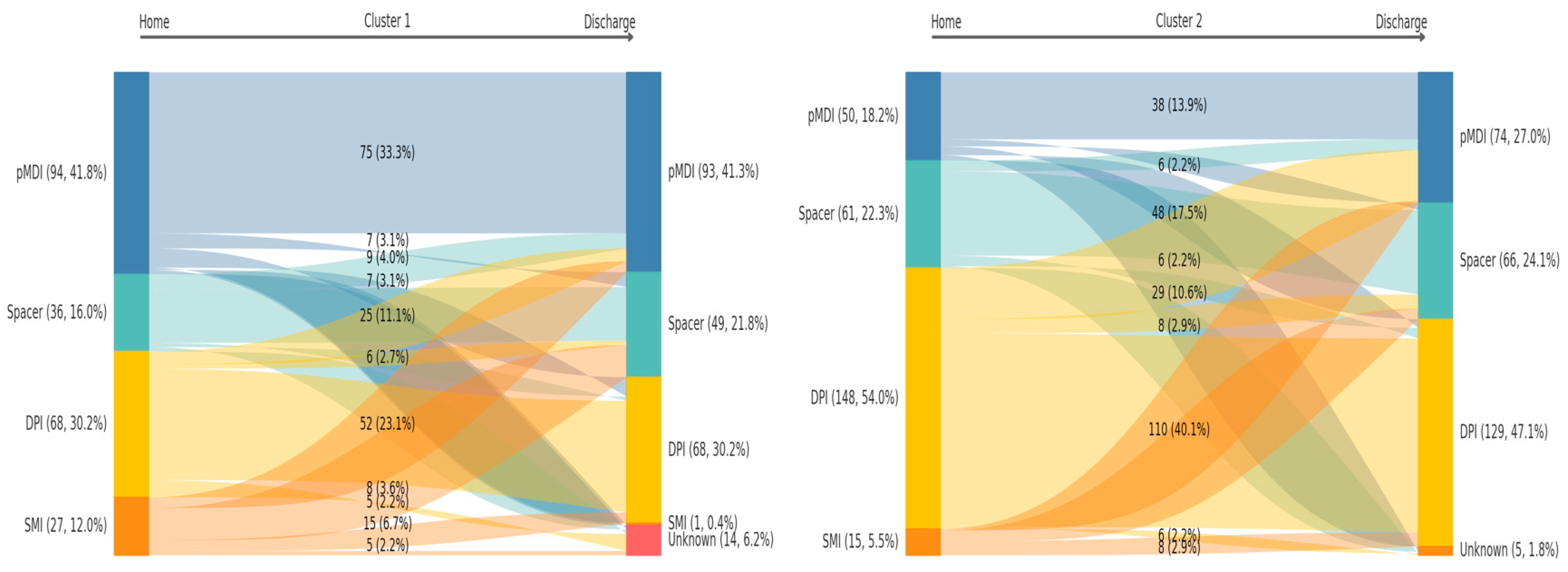

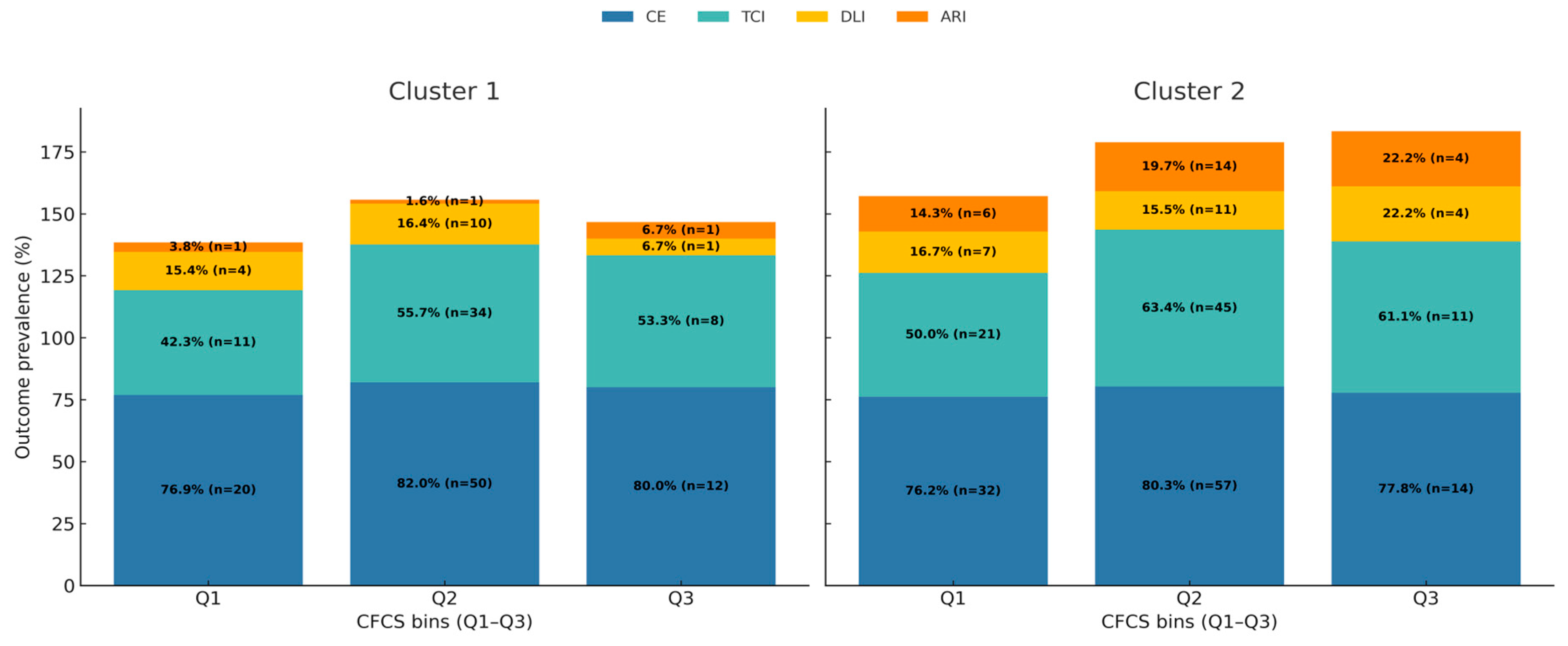

3.1. Characterization of Clinical Phenotypes, Therapeutic Inertia, and Prognostic Relevance

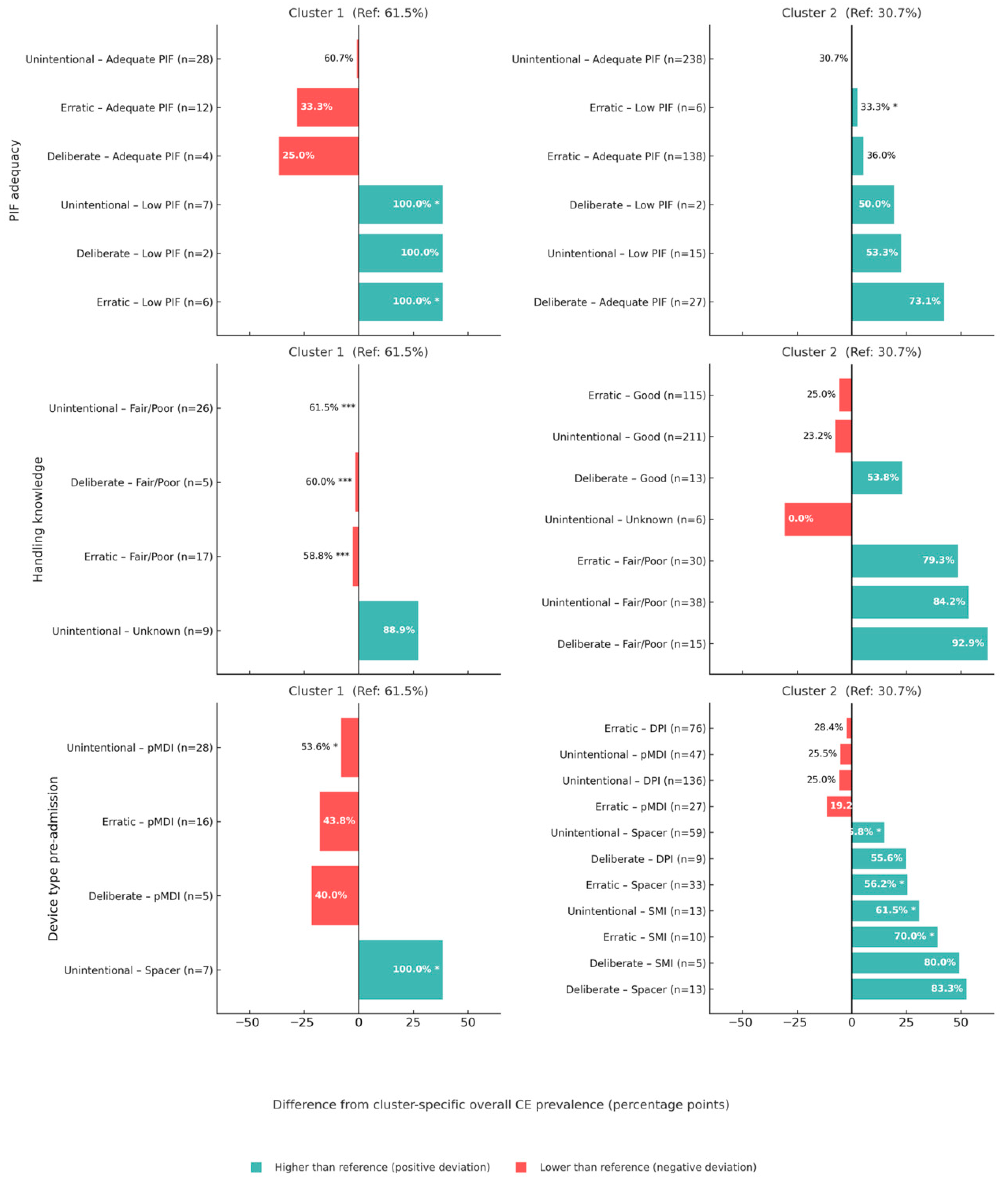

3.2. Deconstruction of Therapeutic Failure: Predictors of Inhaler Misuse

3.3. Synthesis of Dynamic Risk, Effect Modification, and Levers for Corrective Action

4. Discussion

4.1. Patient Phenotypes as Proxies for In-Hospital Care Pathways

4.2. The Anatomy of Clinical Inertia: Context-Specific Drivers of Inaction

4.3. Reframing Inhaler Misuse: It Is Competence, Not Reported Compliance

4.4. A Dynamic Risk Model: How Phenotype Modifies the Relationship Between Function and Failure

4.5. Limitations

4.6. Clinical Implications and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TCI | Therapeutic Class |

| DLI | Device-Level |

| ARI | Adherence-Related |

| CFCS | Clinical Frailty and Competence Score |

| TAI | Test of Adherence to Inhalers |

| DPI | Dry powder inhaler |

| pMDI | Pressurized metered-dose inhaler |

| SMI | Soft mist inhaler |

References

- Safiri, S.; Carson-Chahhoud, K.; Noori, M.; Nejadghaderi, S.A.; Sullman, M.J.M.; Heris, J.A.; Ansarin, K.; Mansournia, M.A.; Collins, G.S.; Kolahi, A.-A.; et al. Burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and its attributable risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: Results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. BMJ 2022, 378, e069679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, S.; Atkins, P.; Bäckman, P.; Cipolla, D.; Clark, A.; Daviskas, E.; Disse, B.; Entcheva-Dimitrov, P.; Fuller, R.; Gonda, I.; et al. Inhaled medicines: Past, present, and future. Pharmacol. Rev. 2022, 74, 48–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodcock, A.; Boucot, I.; Leather, D.A.; Crawford, J.; Collier, S.; Bakerly, N.D.; Hilton, E.; Vestbo, J. Effectiveness versus efficacy trials in COPD: How study design influences outcomes and applicability. Eur. Respir. J. 2018, 51, 1701531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchis, J.; Gich, I.; Pedersen, S. Systematic review of errors in inhaler use: Has patient technique improved over time? Chest 2016, 150, 394–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usmani, O.S.; Lavorini, F.; Marshall, J.; Dunlop, W.C.N.; Heron, L.; Farrington, E.; Dekhuijzen, R. Critical inhaler errors in asthma and COPD: A systematic review of impact on health outcomes. Respir. Res. 2018, 19, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Press, V.G.; Arora, V.M.; Shah, L.M.; Lewis, S.L.; Charbeneau, J.; Naureckas, E.T.; Krishnan, J.A. Teaching the use of respiratory inhalers to hospitalized patients with asthma or COPD: A randomized trial. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2012, 27, 1317–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turégano-Yedro, M.; Trillo-Calvo, E.; Ros, F.N.; Maya-Viejo, J.D.; Villaescusa, C.G.; Sustaeta, J.M.E.; Doña, E.; Navarrete, B.A. Inhaler adherence in COPD: A crucial step towards the correct treatment. Int. J. Chronic Obst. Pulm. Dis. 2023, 18, 2887–2893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavoie, K.L.; Rash, J.A.; Campbell, T.S. Changing provider behavior in the context of chronic disease management: Focus on clinical inertia. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2017, 57, 263–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Hermosa, J.L.; Esmaili, S.; Esmaili, I.; Calle Rubio, M.; Novoa García, C. Decoding diagnostic delay in COPD: An integrative analysis of missed opportunities, clinical risk profiles, and targeted detection strategies in primary care. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calle Rubio, M.; Esmaili, S.; Esmaili, I.; Gómez Martín-Caro, L.; Ayat Ortiz, S.; Rodríguez Hermosa, J.L. Sex-Based Disparities in Clinical Burden and Diagnostic Delay in COPD: Insights from Primary Care. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahler, D.A.; Halpin, D.M.G. Consideration and assessment of patient factors when selecting an inhaled delivery system in COPD. Chest 2024, 165, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, L.; Khoa, N.D.; Chi, L.T.K.; Anh, N.T. Prevalence and factors affecting appropriate inhaler use in elderly patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A prospective study. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 4420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubio, M.C.; Teppa, P.J.A.; Hermosa, J.L.R.; Carro, M.G.; Martínez, J.C.T.; Rubio, C.R.; Cortés, L.F.; Dueñas, M.M.; del Barrio, V.C.; Hoyo, R.S.-D.; et al. Insights from real-world evidence on the use of inhalers in clinical practice. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlson, M.E.; Pompei, P.; Ales, K.L.; MacKenzie, C.R. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J. Chronic Dis. 1987, 40, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaza, V.; Fernández-Rodríguez, C.; Melero, C.; Cosío, B.G.; Entrenas, L.M.; de Llano, L.P.; Gutiérrez-Pereyra, F.; Tarragona, E.; Palomino, R.; López-Viña, A.; et al. Validation of the ‘Test of the Adherence to Inhalers’ (TAI) for asthma and COPD patients. J. Aerosol Med. Pulm. Drug Deliv. 2016, 29, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pankovitch, S.; Frohlich, M.; AlOthman, B.; Marciniuk, J.; Bernier, J.; Paul-Emile, D.; Bourbeau, J.; Ross, B.A. Peak inspiratory flow and inhaler prescription strategies in a specialized COPD clinical program: A real-world observational study. Chest 2025, 167, 736–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.H.; Rockwood, K. Frailty in older adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 538–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlson, M.E.; Carrozzino, D.; Guidi, J.; Patierno, C. Charlson comorbidity index: A critical review of clinimetric properties. Psychother. Psychosom. 2022, 91, 8–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddocks, M.; Brighton, L.J.; Alison, J.A.; ter Beek, L.; Bhatt, S.P.; Brummel, N.E.; Burtin, C.; Cesari, M.; Evans, R.A.; Ferrante, L.E.; et al. Rehabilitation for people with respiratory disease and frailty: An official American Thoracic Society workshop report. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2023, 20, 767–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echevarria, C.; Steer, J.; Bourke, S.C. Coding of COPD exacerbations and the implications on clinical practice, audit and research. COPD 2020, 17, 706–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Campos, J.L.; Carrasco Hernández, L.; Ruiz-Duque, B.; Reinoso-Arija, R.; Caballero-Eraso, C. Step-up and step-down treatment approaches for COPD: A holistic view of progressive therapies. Int. J. Chronic Obst. Pulm. Dis. 2021, 16, 2065–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savarese, G.; Lindberg, F.; Cannata, A.; Chioncel, O.; Stolfo, D.; Musella, F.; Tomasoni, D.; Abdelhamid, M.; Banerjee, D.; Bayes-Genis, A.; et al. How to tackle therapeutic inertia in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: A scientific statement of the Heart Failure Association of the ESC. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2024, 26, 1278–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodcock, A.; Beeh, K.M.; Sagara, H.; Aumônier, S.; Addo-Yobo, E.; Khan, J.; Vestbo, J.; Tope, H. The Environmental Impact of Inhaled Therapy: Making Informed Treatment Choices. Eur. Respir. J. 2022, 60, 2102106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loh, C.H.; Ohar, J.A. Utility of peak inspiratory flow measurement for dry powder inhaler use in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 2024, 30, 174–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnestein-Fonseca, P.; Vázquez-González, N.; Martín-Montañez, E.; Leiva-Fernández, J.; Cotta-Luque, V.; Leiva-Fernández, F. The clinical relevance of inhalation technique in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients. Med. Clin. 2022, 158, 472–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brusselle, G.; Himpe, U.; Fievez, P.; Leys, M.; Bogerd, S.P.; Peché, R.; Vanderhelst, E.; Lins, M.; Capiau, P. Evolving to a single inhaler extrafine LABA/LAMA/ICS—Inhalation technique and adherence at the heart of COPD patient care (TRIVOLVE). Respir. Med. 2023, 218, 107368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrychova, T.; Svoboda, M.; Maly, J.; Vlcek, J.; Zimcikova, E.; Dvorak, T.; Zatloukal, J.; Volakova, E.; Plutinsky, M.; Brat, K.; et al. Self-reported overall adherence and correct inhalation technique discordance in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease population. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 860270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaiman, I.; Cushen, B.; Greene, G.; Seheult, J.; Seow, D.; Rawat, F.; MacHale, E.; Mokoka, M.; Moran, C.N.; Bhreathnach, A.S.; et al. Objective assessment of adherence to inhalers by patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2017, 195, 1333–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, D.; Keininger, D.L.; Viswanad, B.; Gasser, M.; Walda, S.; Gutzwiller, F.S. Factors associated with appropriate inhaler use in patients with COPD—Lessons from the REAL survey. Int. J. Chronic Obst. Pulm. Dis. 2018, 13, 695–702, Erratum in Int. J. Chronic Obst. Pulm. Dis. 2018, 13, 2253–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgari, S.; Khalili, D.; Zayeri, F.; Azizi, F.; Hadaegh, F. Dynamic prediction models improved the risk classification of type 2 diabetes compared with classical static models. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2021, 140, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agusti, A.; Bel, E.; Thomas, M.; Vogelmeier, C.; Brusselle, G.; Holgate, S.; Humbert, M.; Jones, P.; Gibson, P.G.; Vestbo, J.; et al. Treatable traits: Toward precision medicine of chronic airway diseases. Eur. Respir. J. 2016, 47, 410–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, A.J.; Ram, S.; Labaki, W.W.; Murray, S.; Kazerooni, E.A.; Galban, S.; Martinez, F.J.; Hatt, C.R.; Wang, J.M.; Ivanov, V.; et al. Temporal exploration of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease phenotypes: Insights from the COPDGene and SPIROMICS cohorts. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2025, 211, 569–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janjua, S.; Pike, K.C.; Carr, R.; Coles, A.; Fortescue, R.; Batavia, M. Interventions to improve adherence to pharmacological therapy for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD). Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 9, CD013381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Domain/Variable | Overall (n = 499) | Cluster 1 (n = 225) | Cluster 2 (n = 274) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics & Comorbidity | ||||

| Age (years) | 78.0 [69.0–85.0] | 80.0 [70.0–86.0] | 76.0 [67.0–84.0] | 0.010 |

| Charlson comorbidity index | 3.0 [1.0–4.0] | 3.0 [1.0–4.0] | 2.0 [1.0–4.0] | 0.218 |

| Sex | 0.046 | |||

| Female | 165 (33.1) | 66 (29.3) | 99 (36.1) | |

| Male | 243 (48.7) | 108 (48.0) | 135 (49.3) | |

| Not recorded | 91 (18.2) | 51 (22.7) | 40 (14.6) | |

| Respiratory Function & Adherence | ||||

| Peak flow (L/min) | 60.00 [45.00–70.00] | 55.00 [40.00–60.00] | 60.0 [50.0–70.0] | 0.001 |

| Peak flow adequacy | <0.001 | |||

| ≥30 L/min | 291 (58.3) | 39 (17.3) | 252 (92.0) | |

| Unknown | 182 (36.5) | 176 (78.2) | 6 (2.2) | |

| <30 L/min | 26 (5.2) | 10 (4.4) | 16 (5.8) | |

| TAI sum | 48.0 [47.0–48.0] | 48.0 [48.0–48.0] | 48.0 [45.0–50.0] | 0.613 |

| Adherence | <0.001 | |||

| Good | 84 (16.8) | 2 (0.9) | 82 (29.9) | |

| Intermediate | 89 (17.8) | 3 (1.3) | 86 (31.4) | |

| Poor | 106 (21.2) | 16 (7.1) | 90 (32.8) | |

| Unknown | 220 (44.1) | 204 (90.7) | 16 (5.8) | |

| Handling knowledge | <0.001 | |||

| Fair/Poor | 74 (14.8) | 30 (13.3) | 44 (16.1) | |

| Good | 226 (45.3) | 2 (0.9) | 224 (81.8) | |

| Unknown | 199 (39.9) | 193 (85.8) | 6 (2.2) | |

| Device Use | ||||

| Device before admission | <0.001 | |||

| DPI | 216 (43.3) | 68 (30.2) | 148 (54.0) | |

| SMI | 42 (8.4) | 27 (12.0) | 15 (5.5) | |

| Spacer | 97 (19.4) | 36 (16.0) | 61 (22.3) | |

| pMDI | 144 (28.9) | 94 (41.8) | 50 (18.2) | |

| In-hospital device | 0.575 | |||

| DPI only | 14 (2.8) | 7 (3.1) | 7 (2.6) | |

| Neb + pMDI + Spacer | 3 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (1.1) | |

| Neb only | 207 (41.5) | 99 (44.0) | 108 (39.4) | |

| SMI + pMDI | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | |

| SMI only | 11 (2.2) | 7 (3.1) | 4 (1.5) | |

| pMDI + DPI | 3 (0.6) | 1 (0.4) | 2 (0.7) | |

| pMDI only | 257 (51.5) | 109 (48.4) | 148 (54.0) | |

| pMDI + Spacer only | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | |

| Device changed at discharge | 0.038 | |||

| No | 348 (69.7) | 152 (67.6) | 196 (71.5) | |

| Unknown | 19 (3.8) | 14 (6.2) | 5 (1.8) | |

| Yes | 132 (26.5) | 59 (26.2) | 73 (26.6) | |

| Clinical Service & Diagnoses | ||||

| Admitting service (Pulmonology) | 123 (24.6) | 49 (21.8) | 74 (27.0) | 0.177 |

| Dementia diagnosis | 23 (4.6) | 10 (4.4) | 13 (4.7) | 0.874 |

| Heart failure diagnosis | 141 (28.3) | 62 (27.6) | 79 (28.8) | 0.753 |

| Outcomes | ||||

| 90-day mortality | 108 (21.6) | 58 (25.8) | 50 (18.3) | 0.055 |

| Predictor | Level/Contrast | aOR | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenotype | Cluster 2 vs. 1 | 0.45 | 0.20–1.01 | 0.053 |

| Age | per 10-year increase | 1.51 | 1.20–1.89 | <0.001 |

| Sex | Male vs. Female | 1.09 | 0.72–1.65 | 0.682 |

| Charlson comorbidity index | per point | 1.14 | 1.03–1.27 | 0.013 |

| COPD diagnosis | Yes vs. No | 0.54 | 0.33–0.91 | 0.019 |

| Peak flow adequacy | Ref: >30 L/min | |||

| ≤30 L/min | 1.46 | 0.53–4.04 | 0.467 | |

| Unknown | 2.44 | 1.19–5.03 | 0.016 | |

| Admitting service | Ref: Internal Medicine | |||

| Pulmonology | 1.25 | 0.70–2.24 | 0.453 | |

| Other | 0.57 | 0.31–1.05 | 0.071 | |

| Knowledge—patient handling | Ref: Good | <0.001 | ||

| Fair | 0.40 | 0.21–0.76 | 0.005 | |

| Poor | 0.20 | 0.07–0.58 | 0.004 | |

| Very Poor | 0.00 * | 0.00–0.00 | <0.001 | |

| Undocumented | 0.00 * | 0.00–0.00 | <0.001 | |

| In-hospital device | Ref: Nebulizer only | <0.001 | ||

| pMDI only | 0.25 | 0.09–0.74 | 0.016 | |

| SMI only | 0.10 | 0.02–0.51 | 0.007 | |

| DPI only | 0.41 | 0.08–2.08 | 0.283 | |

| Mixed/Combo categories | ~0.00–0.30 | various | <0.05 | |

| Respiratory comorbidity | Ref: COPD | <0.001 | ||

| Asthma | 0.44 | 0.18–1.09 | 0.077 | |

| Bronchiectasis | 0.38 | 0.12–1.20 | 0.098 | |

| Others | 0.49 | 0.19–1.26 | 0.139 | |

| No respiratory comorbidity | 13.75 | 6.20–37.28 | <0.001 |

| Predictor | Adjusted Odds Ratio (aOR) | 95% Confidence Interval (CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Handling knowledge (worse vs. better) | 6.03 | 2.88–12.64 | <0.001 |

| PIF ≤ 30 L/min (vs. >30 L/min) | 3.11 | 1.06–9.12 | 0.038 |

| Deliberate non-adherence (Yes vs. No) | 2.24 | 0.86–5.87 | 0.100 |

| Erratic non-adherence (Yes vs. No) | 1.02 | 0.54–1.93 | 0.943 |

| Pre-Admission Device (Ref: DPI) | |||

| Spacer | 2.13 | 0.89–4.05 | 0.077 |

| SMI | 3.83 | 0.94–12.45 | 0.082 |

| pMDI | 0.95 | 0.45–2.02 | 0.902 |

| Predictor | B (SE) | Wald χ2 | df | aOR | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Therapeutic Class Inertia (TCI)—High-Risk Patients (n = 335) | ||||||

| Phenotype (Cluster 2 vs. 1) | −0.34 (0.67) | 0.27 | 1 | 0.71 | 0.18–2.72 | 0.613 |

| Age (per 10-year increase) | −0.51 (0.13) | 14.9 | 1 | 0.60 | 0.46–0.77 | <0.001 *** |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index (per point) | 0.64 (0.21) | 8.75 | 1 | 1.90 | 1.24–2.91 | 0.003 ** |

| Baseline Therapy Potency (per level) | 2.05 (0.39) | 28.0 | 1 | 7.80 | 3.65–16.64 | <0.001 *** |

| Admitting Service (Ref: Internal Medicine) | ||||||

| Pulmonology | 0.10 (0.83) | 0.02 | 1 | 1.10 | 0.26–4.61 | 0.891 |

| Other | 1.77 (0.82) | 4.67 | 1 | 5.88 | 1.17–29.44 | 0.031 * |

| B.1. Device-Level Inertia (DLI)—Baseline Model (n = 114) | ||||||

| Phenotype (Cluster 2 vs. 1) | −1.84 (1.05) | 3.07 | 1 | 0.16 | 0.02–1.24 | 0.080 |

| Age (per 10-year increase) | −0.58 (0.33) | 3.18 | 1 | 0.56 | 0.30–1.06 | 0.075 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index (per point) | −0.08 (0.12) | 0.43 | 1 | 0.92 | 0.73–1.17 | 0.513 |

| Admitting Service (Ref: Internal Medicine) | ||||||

| Pulmonology | −1.46 (0.76) | 3.67 | 1 | 0.23 | 0.05–1.03 | 0.055 |

| Other | −0.99 (1.33) | 0.55 | 1 | 0.37 | 0.03–5.02 | 0.457 |

| Respiratory Disease (Ref: None) | ||||||

| COPD | 1.51 (1.13) | 1.80 | 1 | 4.54 | 0.50–41.50 | 0.180 |

| Asthma | 1.80 (1.00) | 3.23 | 1 | 6.07 | 0.85–43.31 | 0.072 |

| Bronchiectasis | 0.66 (1.71) | 0.15 | 1 | 1.93 | 0.07–54.86 | 0.702 |

| Pre-admission Device (Ref: pMDI/SMI) | ||||||

| DPI | 0.30 (0.85) | 0.13 | 1 | 1.35 | 0.25–7.23 | 0.722 |

| Spacer | 0.56 (0.83) | 0.45 | 1 | 1.75 | 0.35–8.84 | 0.500 |

| B.2. Device-Level Inertia (DLI)—Expanded Model with Training Variables (n = 101) | ||||||

| Age (per 10-year increase) | 1.06 | 0.74–1.51 | 0.760 | |||

| Charlson (per point) | 0.99 | 0.81–1.20 | 0.900 | |||

| Service: Pulmonology (vs. Internal Medicine) | 1.00 | 0.25–4.00 | 1.000 | |||

| Service: Other (vs. Internal Medicine) | 1.00 | 0.25–4.00 | 1.000 | |||

| Pre-admission device: DPI (vs. pMDI/SMI) | 1.26 | 0.54–2.97 | 0.596 | |||

| Pre-admission device: Spacer (vs. pMDI/SMI) | 1.36 | 0.59–3.16 | 0.475 | |||

| In-hospital device: SMI only (vs. Nebulizer only) | 0.31 | 0.09–1.05 | 0.061 | |||

| In-hospital device: pMDI only (vs. Nebulizer only) | 1.00 | 0.46–2.17 | 1.000 | |||

| In-hospital device: Mixed (vs. Nebulizer only) | 1.00 | 0.29–3.39 | 1.000 | |||

| In-hospital device: DPI/Spacer only (vs. Nebulizer only) | 1.64 | 0.49–5.46 | 0.418 | |||

| Any inhaler training documented (vs. none/unknown) | 1.41 | 0.59–3.40 | 0.439 | |||

| Trainer = Pharmacy or Specialist | 1.00 | 0.41–2.42 | 1.000 | |||

| Training rating: Poor/Very poor | 1.00 | 0.37–2.70 | 1.000 | |||

| Training: Did not receive | 3.49 | 1.21–10.03 | 0.020 * | |||

| C. Adherence-Related Inertia (ARI)—Patients with Documented Poor Adherence (n = 106) | ||||||

| Phenotype (Cluster 2 vs. 1) | 1.19 (0.80) | 2.22 | 1 | 3.29 | 0.67–16.14 | 0.142 |

| Age (per 10-year increase) | 0.26 (0.18) | 2.18 | 1 | 1.29 | 0.92–1.82 | 0.140 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index (per point) | –0.14 (0.15) | 0.90 | 1 | 0.87 | 0.65–1.16 | 0.342 |

| Home Maintenance Inhalers (per device) | –2.81 (0.65) | 18.7 | 1 | 0.06 | 0.02–0.25 | <0.001 *** |

| Predictor | Adjusted Odds Ratio (aOR) | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (per 10-year increase) | 0.89 | 0.76–1.04 | 0.148 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index (per point) | 0.96 | 0.87–1.05 | 0.333 |

| Service (Ref: Internal Medicine) | |||

| Pulmonology | 1.00 | 0.25–4.00 | 1.000 |

| Other | 0.88 | 0.22–3.51 | 0.853 |

| Pre-admission device (Ref: DPI) | |||

| pMDI/SMI | 1.85 | 1.21–2.82 | 0.004 ** |

| Spacer | 1.00 | 0.58–1.72 | 1.000 |

| In-hospital device (Ref: Nebulizer only) | |||

| SMI only | 2.79 | 1.10–7.09 | 0.031 * |

| pMDI only | 1.02 | 0.68–1.52 | 0.926 |

| Mixed | 1.00 | 0.35–2.82 | 1.000 |

| DPI only/Spacer only | 0.22 | 0.07–0.68 | 0.009 ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Calle Rubio, M.; Esmaili, S.; Rodríguez Hermosa, J.L.; Esmaili, I.; Adami Teppa, P.J.; García Carro, M.; Tallón Martínez, J.C.; Nieto Sánchez, Á.; Riesco Rubio, C.; Fernández Cortés, L.; et al. Deconstructing Therapeutic Failure with Inhaled Therapy in Hospitalized Patients: Phenotypes, Risk Profiles, and Clinical Inertia. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2892. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122892

Calle Rubio M, Esmaili S, Rodríguez Hermosa JL, Esmaili I, Adami Teppa PJ, García Carro M, Tallón Martínez JC, Nieto Sánchez Á, Riesco Rubio C, Fernández Cortés L, et al. Deconstructing Therapeutic Failure with Inhaled Therapy in Hospitalized Patients: Phenotypes, Risk Profiles, and Clinical Inertia. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(12):2892. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122892

Chicago/Turabian StyleCalle Rubio, Myriam, Soha Esmaili, Juan Luis Rodríguez Hermosa, Iman Esmaili, Pedro José Adami Teppa, Miriam García Carro, José Carlos Tallón Martínez, Ángel Nieto Sánchez, Consolación Riesco Rubio, Laura Fernández Cortés, and et al. 2025. "Deconstructing Therapeutic Failure with Inhaled Therapy in Hospitalized Patients: Phenotypes, Risk Profiles, and Clinical Inertia" Biomedicines 13, no. 12: 2892. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122892

APA StyleCalle Rubio, M., Esmaili, S., Rodríguez Hermosa, J. L., Esmaili, I., Adami Teppa, P. J., García Carro, M., Tallón Martínez, J. C., Nieto Sánchez, Á., Riesco Rubio, C., Fernández Cortés, L., Morales Dueñas, M., Chamorro del Barrio, V., & Gao, X. (2025). Deconstructing Therapeutic Failure with Inhaled Therapy in Hospitalized Patients: Phenotypes, Risk Profiles, and Clinical Inertia. Biomedicines, 13(12), 2892. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122892