Prematurity and Epigenetic Regulation of SLC6A4: Longitudinal Insights from Birth to the First Month of Life

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Study Population and Ethics

2.2. Study Variables

2.3. Biological Material Collection

2.4. SLC6A4 Methylation Analysis

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Epidemiological and Clinical Characteristics of the Study Population

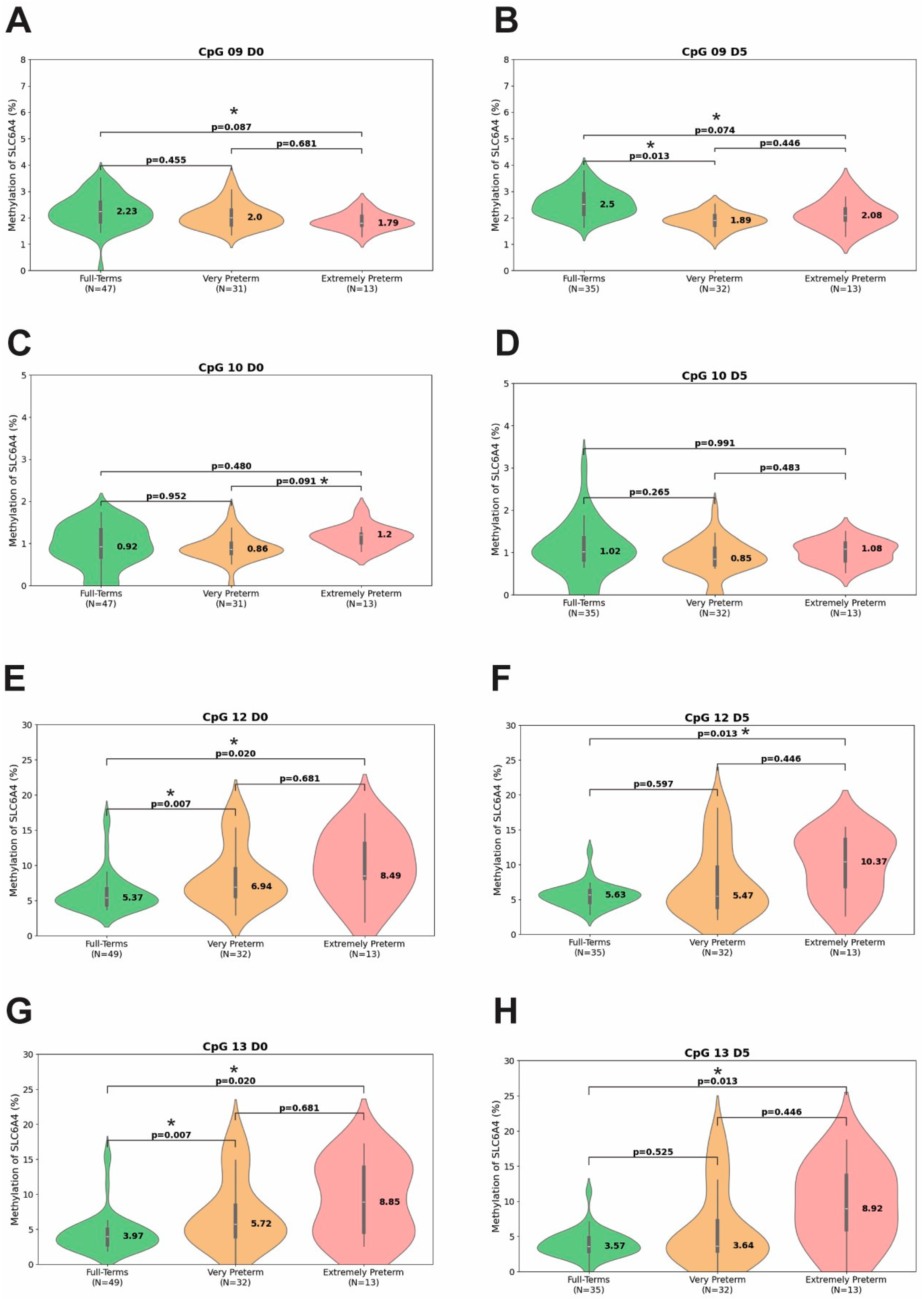

3.2. Methylation Percentage at Different Time Points

3.3. Longitudinal Dynamics of SLC6A4 Methylation in Preterm Infants

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADHD | Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder |

| CBCL | Child Behavior Checklist |

| CNS | Central Nervous System |

| COMT | Catechol-O-Methyltransferase |

| CpG | Cytosine–phosphate–Guanine dinucleotide |

| DAG | Directed Acyclic Graph |

| D0 | Day of birth |

| D5 | Fifth day of life |

| D30 | Thirtieth day of life |

| EDTA | Ethylenediaminetetraacetic Acid |

| EPT | Extremely Preterm |

| FDR | False Discovery Rate |

| FT | Full-Term |

| gDNA | Genomic DNA |

| HPA | Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (axis) |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| LGA | Large for Gestational Age |

| LMP | Last Menstrual Period |

| MAO | Monoamine Oxidase |

| NICU | Neonatal Intensive Care Unit |

| NISS | Neonatal Infant Stressor Scale |

| NR3C1 | Nuclear Receptor Subfamily 3 Group C Member 1 (Glucocorticoid Receptor Gene) |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| SAS | Statistical Analysis System |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SGA | Small for Gestational Age |

| SLC6A4 | Solute Carrier Family 6 Member 4 (Serotonin Transporter Gene) |

| USG | Ultrasound |

| VPT | Very Preterm |

References

- United Nations Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation (UN IGME). Levels & Trends in Child Mortality: Report 2024–Estimates Developed by the United Nations Inter-Agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation; United Nations Children’s Fund: New York, NY, USA, 2025; ISBN 9789280656367. [Google Scholar]

- Ream, M.A.; Lehwald, L. Neurologic Consequences of Preterm Birth. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2018, 18, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, E.H.; Chou, J.; Brown, K.A. Neurodevelopmental Outcomes of Preterm Infants: A Recent Literature Review. Transl. Pediatr. 2020, 9, S3–S8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, L.; Nivins, S.; Chen, X.; Liang, Y.; Gissler, M.; Lavebratt, C. Association of Preterm Birth and Birth Size Status with Neurodevelopmental and Psychiatric Disorders in Spontaneous Births. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2025, 34, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnett, A.; Axford, S.B.; Seid, A.M.; Anderson, P.J.; Waterland, J.L.; Gilchrist, C.P.; Olsen, J.; Nguyen, N.; Spittle, A.; Doyle, L.W.; et al. Predicting Long-Term Neurodevelopmental Outcomes for Children Born Very Preterm: A Systematic Review. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinall, J.; Grunau, R.E. Impact of Repeated Procedural Pain-Related Stress in Infants Born Very Preterm. Pediatr. Res. 2014, 75, 584–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranger, M.; Chau, C.M.Y.; Garg, A.; Woodward, T.S.; Beg, M.F.; Bjornson, B.; Poskitt, K.; Fitzpatrick, K.; Synnes, A.R.; Miller, S.P.; et al. Neonatal Pain-Related Stress Predicts Cortical Thickness at Age 7 Years in Children Born Very Preterm. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e76702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provenzi, L.; Fumagalli, M.; Sirgiovanni, I.; Giorda, R.; Pozzoli, U.; Morandi, F.; Beri, S.; Menozzi, G.; Mosca, F.; Borgatti, R.; et al. Pain-Related Stress during the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Stay and SLC6A4 Methylation in Very Preterm Infants. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brummelte, S.; Grunau, R.E.; Chau, V.; Poskitt, K.J.; Brant, R.; Vinall, J.; Gover, A.; Synnes, A.R.; Miller, S.P. Procedural Pain and Brain Development in Premature Newborns. Ann. Neurol. 2012, 71, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eckstein Grunau, R. Neonatal Pain in Very Preterm Infants: Long-Term Effects on Brain, Neurodevelopment and Pain Reactivity. Rambam Maimonides Med. J. 2013, 4, e0025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Born Too Soon: Decade of Action on Preterm Birth. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240073890 (accessed on 7 December 2024).

- Montirosso, R.; Provenzi, L. Implications of Epigenetics and Stress Regulation on Research and Developmental Care of Preterm Infants. JOGNN-J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2015, 44, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.Z.; Nusslock, R. How Stress Gets Under the Skin: Early Life Adversity and Glucocorticoid Receptor Epigenetic Regulation. Curr. Genom. 2017, 19, 653–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalfun, G.; Reis, M.M.; de Oliveira, M.B.G.; de Araújo Brasil, A.; dos Santos Salú, M.; da Cunha, A.J.L.A.; Prata-Barbosa, A.; de Magalhães-Barbosa, M.C. Perinatal Stress and Methylation of the NR3C1 Gene in Newborns: Systematic Review. Epigenetics 2021, 17, 1003–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Padua Andrade Campanha, P.; de Magalhães-Barbosa, M.C.; de Araújo Brasil, A.; Paravidino, V.B.; Soares-Lima, S.C.; de Souza Almeida Lopes, M.; dos Santos, P.V.B.E.; Milone, L.T.V.; dos Santos Salú, M.; de Oliveira Saide, S.C.A.; et al. Methylation of the Glucocorticoid Receptor Gene (NR3C1) in Preterm Infants Undergoing Kangaroo Mother Care Method. Epigenet. Rep. 2025, 3, 2545608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, I.C.G.; Cervoni, N.; Champagne, F.A.; D’Alessio, A.C.; Sharma, S.; Seckl, J.R.; Dymov, S.; Szyf, M.; Meaney, M.J. Epigenetic Programming by Maternal Behavior. Nat. Neurosci. 2004, 7, 847–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, R.A.; Kochanska, G.; Philibert, R.A. G x E Interaction in the Organization of Attachment: Mothers’ Responsiveness as a Moderator of Children’s Genotypes. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 2008, 49, 1313–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conradt, E.; Ostlund, B.; Guerin, D.; Armstrong, D.A.; Marsit, C.J.; Tronick, E.; LaGasse, L.; Lester, B.M. DNA Methylation of NR3c1 in Infancy: Associations between Maternal Caregiving and Infant Sex. Infant Ment. Health J. 2019, 40, 513–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krol, K.M.; Moulder, R.G.; Lillard, T.S.; Grossmann, T.; Connelly, J.J. Epigenetic Dynamics in Infancy and the Impact of Maternal Engagement. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaay0680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, C.; Marasca, F.; Provitera, L.; Mancinelli, S.; Pesenti, N.; Sinha, S.; Passera, S.; Abrignani, S.; Mosca, F.; Lodato, S.; et al. Early Maternal Care Restores LINE-1 Methylation and Enhances Neurodevelopment in Preterm Infants. BMC Med. 2021, 19, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani Wigley, I.L.C.; Mascheroni, E.; Fontana, C.; Giorda, R.; Morandi, F.; Bonichini, S.; McGlone, F.; Fumagalli, M.; Montirosso, R. The Role of Maternal Touch in the Association between SLC6A4 Methylation and Stress Response in Very Preterm Infants. Dev. Psychobiol. 2021, 63, e22218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hood, S.D.; Hince, D.A.; Robinson, H.; Cirillo, M.; Christmas, D.; Kaye, J.M. Serotonin Regulation of the Human Stress Response. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2006, 31, 1087–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanswijk, S.I.; Spoelder, M.; Shan, L.; Verheij, M.M.M.; Muilwijk, O.G.; Li, W.; Liu, C.; Kolk, S.M.; Homberg, J.R. Gestational Factors throughout Fetal Neurodevelopment: The Serotonin Link. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canli, T.; Lesch, K.P. Long Story Short: The Serotonin Transporter in Emotion Regulation and Social Cognition. Nat. Neurosci. 2007, 10, 1103–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauli-Pott, U.; Friedl, S.; Hinney, A.; Hebebrand, J. Serotonin Transporter Gene Polymorphism (5-HTTLPR), Environmental Conditions, and Developing Negative Emotionality and Fear in Early Childhood. J. Neural Transm. 2009, 116, 503–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mueller, A.; Armbruster, D.; Moser, D.A.; Canli, T.; Lesch, K.P.; Brocke, B.; Kirschbaum, C. Interaction of Serotonin Transporter Gene-Linked Polymorphic Region and Stressful Life Events Predicts Cortisol Stress Response. Neuropsychopharmacology 2011, 36, 1332–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, B.B.; Hunter, R.G. Neuroepigenetics of Stress. Neuroscience 2014, 275, 420–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beach, S.R.H.; Brody, G.H.; Todorov, A.A.; Gunter, T.D.; Philibert, R.A. Methylation at SLC6A4 Is Linked to Family History of Child Abuse: An Examination of the Iowa Adoptee Sample. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2010, 153, 710–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fumagalli, M.; Provenzi, L.; De Carli, P.; Dessimone, F.; Sirgiovanni, I.; Giorda, R.; Cinnante, C.; Squarcina, L.; Pozzoli, U.; Triulzi, F.; et al. From Early Stress to 12-Month Development in Very Preterm Infants: Preliminary Findings on Epigenetic Mechanisms and Brain Growth. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0190602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Dai, Z.; Yu, J.; Xiao, M. CpG-Island-Based Annotation and Analysis of Human Housekeeping Genes. Brief. Bioinform. 2021, 22, 515–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younesian, S.; Yousefi, A.M.; Momeny, M.; Ghaffari, S.H.; Bashash, D. The DNA Methylation in Neurological Diseases. Cells 2022, 11, 3439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefi, P.D.; Suderman, M.; Langdon, R.; Whitehurst, O.; Davey Smith, G.; Relton, C.L. DNA Methylation-Based Predictors of Health: Applications and Statistical Considerations. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2022, 23, 369–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koetsier, J.; Cavill, R.; Reijnders, R.; Harvey, J.; Homann, J.; Kouhsar, M.; Deckers, K.; Köhler, S.; Eijssen, L.M.T.; van den Hove, D.L.A.; et al. Blood-Based Multivariate Methylation Risk Score for Cognitive Impairment and Dementia. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2024, 20, 6682–6698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.H.; Bo, H.H.; Liu, B.P.; Jia, C.X. The Associations between DNA Methylation and Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 327, 439–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidovič, E.; Pelikan, S.; Atanasova, M.; Kouter, K.; Pileckyte, I.; Oblak, A.; Novak Šarotar, B.; Videtič Paska, A.; Bon, J. DNA Methylation Patterns in Relation to Acute Severity and Duration of Anxiety and Depression. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2023, 45, 7286–7303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakusic, J.; Ghosh, M.; Polli, A.; Bekaert, B.; Schaufeli, W.; Claes, S.; Godderis, L. Role of NR3C1 and SLC6A4 Methylation in the HPA Axis Regulation in Burnout. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 295, 505–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provenzi, L.; Fumagalli, M.; Giorda, R.; Morandi, F.; Sirgiovanni, I.; Pozzoli, U.; Mosca, F.; Borgatti, R.; Montirosso, R. Maternal Sensitivity Buffers the Association between SLC6A4 Methylation and Socio-Emotional Stress Response in 3-Month-Old Full Term, but Not Very Preterm Infants. Front. Psychiatry 2017, 8, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provenzi, L.; Fumagalli, M.; Scotto di Minico, G.; Giorda, R.; Morandi, F.; Sirgiovanni, I.; Schiavolin, P.; Mosca, F.; Borgatti, R.; Montirosso, R. Pain-Related Increase in Serotonin Transporter Gene Methylation Associates with Emotional Regulation in 4.5-Year-Old Preterm-Born Children. Acta Paediatr. Int. J. Paediatr. 2020, 109, 1166–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalfun, G.; de Araújo Brasil, A.; Paravidino, V.B.; Soares-Lima, S.C.; de Souza Almeida Lopes, M.; dos Santos Salú, M.; Barbosa E dos Santos, P.V.; da Cunha Trompiere, A.C.P.; Vieira Milone, L.T.; Rodrigues-Santos, G.; et al. NR3C1 Gene Methylation and Cortisol Levels in Preterm and Healthy Full-Term Infants in the First 3 Months of Life. Epigenomics 2023, 14, 1545–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capurro, H.; Konichezky, S.; Fonseca, D.; Caldeyro-Barcia, R. A Simplified Method for Diagnosis of Gestational Age in the Newborn Infant. J. Pediatr. 1978, 93, 120–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballard, J.L.; Khoury, J.C.; Wang, L.; Eilers-Walsman, B.L.; Lipp, R.; Ballard, J.L. New Ballard Score, expanded to include extremely premature infants. J. Pediatr. 1991, 119, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klaus-Peter, L.; Dietmar, B.; Armin, H.; Sabol Sue, Z.; Muller Clemes, R.; Hamer Dean, H.; Murphy Dennis, L. Association of Anxiety-Related Traits a Polymorphism in the Serotonin Transporter Gene Regulatory Region. Science 1996, 274, 1527–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, S.L.; Dodelzon, K.; Sandhu, H.K.; Philibert, R.A. Relationship of Serotonin Transporter Gene Polymorphisms and Haplotypes to MRNA Transcription. Am. J. Med. Genet.-Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2005, 136, 58–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Goldberg, J.; Bremner, J.D.; Vaccarino, V. Association between Promoter Methylation of Serotonin Transporter Gene and Depressive Symptoms: A Monozygotic Twin Study. Psychosom. Med. 2013, 75, 523–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendland, J.R.; Martin, B.J.; Kruse, M.R.; Lesch, K.P.; Murphy, D.L. Simultaneous Genotyping of Four Functional Loci of Human SLC6A4, with a Reappraisal of 5-HTTLPR and Rs25531. Mol. Psychiatry 2006, 11, 224–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iurescia, S.; Seripa, D.; Rinaldi, M. Looking Beyond the 5-HTTLPR Polymorphism: Genetic and Epigenetic Layers of Regulation Affecting the Serotonin Transporter Gene Expression. Mol. Neurobiol. 2017, 54, 8386–8403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, M.K. Molecular Pathways Linking the Serotonin Transporters (SERT) to Depressive Disorder: From Mechanisms to Treatments. Neuroscience 2025, 584, 2–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suktas, A.; Ekalaksananan, T.; Aromseree, S.; Bumrungthai, S.; Songserm, N.; Pientong, C. Genetic Polymorphism Involved in Major Depressive Disorder: A Systemic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2024, 24, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Provenzi, L.; Giorda, R.; Beri, S.; Montirosso, R. SLC6A4 Methylation as an Epigenetic Marker of Life Adversity Exposures in Humans: A Systematic Review of Literature. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2016, 71, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provenzi, L.; Guida, E.; Montirosso, R. Preterm Behavioral Epigenetics: A Systematic Review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2018, 84, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provenzi, L.; Mambretti, F.; Villa, M.; Grumi, S.; Citterio, A.; Bertazzoli, E.; Biasucci, G.; Decembrino, L.; Falcone, R.; Gardella, B.; et al. The Hidden Pandemic: COVID-19-Related Stress, SLC6A4 Methylation, and Infants’ Temperament at 3 Months. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2021, 131, 105508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazzari, S.; Grumi, S.; Mambretti, F.; Villa, M.; Giorda, R.; Provenzi, L.; Borgatti, R.; Biasucci, G.; Decembrino, L.; Giacchero, R.; et al. Maternal and Infant NR3C1 and SLC6A4 Epigenetic Signatures of the COVID-19 Pandemic Lockdown: When Timing Matters. Transl. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbosa Eleutério dos Santos, P.V.; de Araújo Brasil, A.; Vieira Milone, L.T.; Chalfun, G.; Alves de Oliveira Saide, S.C.; dos Santos Salú, M.; Genuíno de Oliveira, M.B.; Robaina, J.R.; Lima-Setta, F.; Rodrigues-Santos, G.; et al. Impact of Prematurity on LINE-1 Promoter Methylation. Epigenomics 2024, 16, 1253–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dokkum, N.H.; Bao, M.; Verkaik-Schakel, R.N.; Reijneveld, S.A.; Bos, A.F.; de Kroon, M.L.A.; Plösch, T. Neonatal Stress Exposure and DNA Methylation of Stress-Related and Neurodevelopmentally Relevant Genes: An Exploratory Study. Early Hum. Dev. 2023, 186, 105868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Szyf, M.; Benkelfat, C.; Provençal, N.; Turecki, G.; Caramaschi, D.; Côté, S.M.; Vitaro, F.; Tremblay, R.E.; Booij, L. Peripheral SLC6A4 DNA Methylation Is Associated with in Vivo Measures of Human Brain Serotonin Synthesis and Childhood Physical Aggression. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e39501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philibert, R.A.; Sandhu, H.; Hollenbeck, N.; Gunter, T.; Adams, W.; Madan, A. Rapid Publication: The Relationship of 5HTT (SLC6A4) Methylation and Genotype on MRNA Expression and Liability to Major Depression and Alcohol Dependence in Subjects from the Iowa Adoption Studies. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2008, 147, 543–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vijayendran, M.; Beach, S.R.H.; Plume, J.M.; Brody, G.H.; Philibert, R.A. Effects of Genotype and Child Abuse on DNA Methylation and Gene Expression at the Serotonin Transporter. Front. Psychiatry 2012, 3, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, N.; Wankerl, M.; Hennig, J.; Miller, R.; Zänkert, S.; Steudte-Schmiedgen, S.; Stalder, T.; Kirschbaum, C. DNA Methylation Profiles within the Serotonin Transporter Gene Moderate the Association of 5-HTTLPR and Cortisol Stress Reactivity. Transl. Psychiatry 2014, 4, e443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, C.M.Y.; Ranger, M.; Sulistyoningrum, D.; Devlin, A.M.; Obertander, T.F.; Grunau, R.E. Neonatal Pain and Comt Val158Met Genotype in Relation to Serotonin Transporter (SLC6A4) Promoter Methylation in Very Preterm Children at School Age. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dannlowski, U.; Kugel, H.; Redlich, R.; Halik, A.; Schneider, I.; Opel, N.; Grotegerd, D.; Schwarte, K.; Schettler, C.; Ambrée, O.; et al. Serotonin Transporter Gene Methylation Is Associated with Hippocampal Gray Matter Volume. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2014, 35, 5356–5367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boggini, T.; Pozzoli, S.; Schiavolin, P.; Erario, R.; Mosca, F.; Brambilla, P.; Fumagalli, M. Cumulative Procedural Pain and Brain Development in Very Preterm Infants: A Systematic Review of Clinical and Preclinical Studies. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 123, 320–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Primer | Sequence (5′-3′) a | Sequence to Analyze b | CpG Sites | Product Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forward | GGTTTTTATATGGTTTGATTTTTAGA | TYGTYGTTAA AGAGTTTTTG AAGAATTTTT G | 1–2 | 70 bp |

| Reverse | /5Biosg/CAAAATAACCCAAAAATTCTTCAAAAACT | |||

| Sequencing | TTTATATGGTTTGATTTTTAGATAG | |||

| Forward | ATATGGTTTGATTTTTAGATAGTAGT | TTTTGYGTTA TTTTGAGGYG AATAAATTTA ATGTTTTTT YGYGGTYGYG GTTTYGYGTT TTYGTT | 3–11 | 128 bp |

| Reverse | /5Biosg/AACCCAACCCCATCCAAC | |||

| Sequencing | GTTAAAGAGTTTTTGAAGAAT | |||

| Forward | TGAGGCG4AATAAATTTAATGTT | TTGYGTTYGT TAGGGAGGGG TYGYGTTAYG GGGYGGGGTG YGYGTTYGAT TTTAGA | 12–13 | 132 bp |

| Reverse | /5Biosg/CCCCTCCTAACTCTAAAAT | |||

| Sequencing | GTTTTAGTTGGATGGGG |

| Characteristics | Preterm (n = 46) | Full-Term (n = 49) |

|---|---|---|

| Maternal Age (years): median (IQR) | 31 (25.2–34) | 27 (23.5–33.5) |

| Maternal Education (years): n (%) | ||

| 1–4 | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0) |

| 5–8 | 7 (15.2) | 9 (18.4) |

| 9–11 | 8 (17.4) | 13 (26.5) |

| >12 | 30 (65.2) | 27 (55.1) |

| a Family Income (national minimum wage): n (%) | ||

| <1 | 13 (28.3) | 4 (8.2) |

| 1–2 | 17 (37) | 28 (57.1) |

| >2 | 16 (34.8) | 15 (30.6) |

| Ethnicity: n (%) | ||

| White | 19 (41.3) | 22 (44.9) |

| Black | 12 (26.1) | 5 (10.2) |

| Brown-skinned (mixed-race ancestry) | 15 (32.6) | 22 (44.9) |

| Health Conditions | ||

| Smokers: n (%) | ||

| No | 43 (93.5) | 46 (93.9) |

| Yes | 3 (6.5) | 3 (6.1) |

| Alcohol Consumption: n (%) | ||

| No | 42 (91.3) | 48 (98) |

| Yes | 4 (8.7) | 1 (2) |

| Perinatal Consultations: median (IQR) | 5 (4–7) | 9 (7–10) |

| Gestational Age (weeks): median (IQR) | 28 (27–30) | 39 (38–40) |

| Apgar Score (1 min): median (IQR) | 7 (4.2–8) | 8 (8–9) |

| Apgar Score (5 min): median (IQR) | 8.5 (8–9) | 9 (9–9) |

| Sex: n (%) | ||

| Male | 25 (54.3) | 25 (51) |

| Female | 20 (43.5) | 24 (49) |

| Undetermined | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0) |

| Birth Weight (g) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 1074.2 (289.9) | 3393.6 (385.0) |

| Median (IQR) | 1075 (860–1345) | 3320 (3150–3575) |

| Length (cm) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 35.9 (1.8) | 48.9 (3.4) |

| Median (IQR) | 36.35 (34–37.5) | 49 (47.5–49.6) |

| Head Circumference (cm) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 26 (2.4) | 34.4 (1.5) |

| Median (IQR) | 26 (24.7–28) | 34 (33.5–35) |

| CpG | Full-Term (%) (IQR) | Preterm (%) (IQR) | p-Value a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D0 Full-term (n = 49) Preterm (n = 46) | 1 | 2.28 (1.76–2.81) | 2.36 (1.62–2.85) | 0.983 |

| 2 | 2.14 (1.70–2.86) | 2.47 (1.97–3.29) | 0.263 | |

| 3 | 1.96 (1.74–2.35) | 2.14 (1.70–2.65) | 0.953 | |

| 4 | 2.16 (1.70–2.41) | 2.08 (1.85–2.40) | 0.983 | |

| 5 | 2.57 (2.18–2.93) | 2.65 (2.32–3.08) | 0.953 | |

| 6 | 1.01 (0.84–1.27) | 1.11 (0.89–1.26) | 0.709 | |

| 7 | 1.32 (1.00–1.59) | 1.37 (1.10–1.66) | 0.709 | |

| 8 | 0.81 (0.57–1.14) | 0.86 (0.71–1.09) | 0.953 | |

| 9 | 2.23 (1.85–2.58) | 1.91 (1.71–2.20) | 0.126 | |

| 10 | 0.92 (0.68–1.33) | 0.92 (0.81–1.20) | 0.983 | |

| 11 | 1.46 (1.03–1.95) | 1.44 (1.14–1.84) | 0.983 | |

| 12 | 5.37 (4.39–6.64) | 7.64 (5.58–12.35) | 0.007 | |

| 13 | 3.97 (2.78–5.01) | 6.03 (4.01–12.59) | 0.007 | |

| D5 Full-term (n = 35) b Preterm (n = 45) b | 1 | 2.38 (1.94–3.07) | 2.09 (1.71–3.24) | 0.594 |

| 2 | 2.48 (2.16–2.86) | 2.05 (1.84–3.06) | 0.318 | |

| 3 | 2.23 (1.84–2.32) | 2.07 (1.74–2.44) | 0.594 | |

| 4 | 2.11 (1.84–2.46) | 2.01 (1.75–2.22) | 0.318 | |

| 5 | 2.74 (2.41–3.05) | 2.72 (2.29–3.01) | 0.594 | |

| 6 | 1.12 (0.95–1.35) | 1.1 (0.85–1.33) | 0.594 | |

| 7 | 1.49 (1.25–1.76) | 1.34 (1.12–1.59) | 0.318 | |

| 8 | 1.07 (0.71–1.24) | 0.88 (0.71–1.14) | 0.318 | |

| 9 | 2.5 (2.14–2.91) | 1.93 (1.72–2.14) | 0.013 | |

| 10 | 1.02 (0.83–1.34) | 0.88 (0.74–1.17) | 0.318 | |

| 11 | 1.57 (1.28–2.21) | 1.39 (1.21–1.73) | 0.318 | |

| 12 | 5.63 (4.6–6.27) | 6.94 (4.01–12.98) | 0.318 | |

| 13 | 3.57 (2.85–4.83) | 4.3 (3.11–11.9) | 0.312 | |

| D30 Full-term (n = 0) b Preterm (n = 36) b | 1 | N/A | 2.26 (1.77–2.75) | N/A |

| 2 | N/A | 2.60 (1.85–3.04) | N/A | |

| 3 | N/A | 2.28 (1.93–2.51) | N/A | |

| 4 | N/A | 2.18 (1.98–2.64) | N/A | |

| 5 | N/A | 2.95 (2.57–3.22) | N/A | |

| 6 | N/A | 1.20 (1.04–1.48) | N/A | |

| 7 | N/A | 1.40 (1.21–1.57) | N/A | |

| 8 | N/A | 0.98 (0.78–1.17) | N/A | |

| 9 | N/A | 2.10 (1.91–2.37) | N/A | |

| 10 | N/A | 1.06 (0.92–1.26) | N/A | |

| 11 | N/A | 1.53 (1.32–1.80) | N/A | |

| 12 | N/A | 7.21 (5.55–13.69) | N/A | |

| 13 | N/A | 6.24 (3.97–13.92) | N/A |

| CpG | Full-Term (%) (IQR) | Very Preterm (%) (IQR) | Extremely Preterm (%) (IQR) | FT vs. VPT p-Value c | FT vs. EPT p-Value c | VPT vs. EPT p-Value c | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D0 Full-term (n = 49) Very preterm (n = 33) Extremely preterm (n = 13) | 1 | 2.28 (1.76–2.81) | 2.40 (1.61–3.25) | 2.23 (1.71–2.63) | 0.952 | 0.749 | 0.681 |

| 2 | 2.14 (1.70–2.86) | 2.51 (1.96–3.36) | 2.42 (2.03–2.90) | 0.394 | 0.556 | 0.915 | |

| 3 | 1.96 (1.74–2.35) | 2.07 (1.61–2.52) | 2.32 (1.78–2.67) | 1.000 | 0.479 | 0.681 | |

| 4 | 2.16 (1.70–2.41) | 2.07 (1.85–2.30) | 2.24 (1.91–2.48) | 0.952 | 0.629 | 0.681 | |

| 5 | 2.57 (2.18–2.93) | 2.57 (2.32–3.08) | 2.74 (2.44–3.13) | 1.000 | 0.602 | 0.681 | |

| 6 | 1.01 (0.84–1.27) | 1.05 (0.88–1.22) | 1.20 (0.99–1.55) | 0.952 | 0.358 | 0.681 | |

| 7 | 1.32 (1.00–1.59) | 1.35 (1.15–1.50) | 1.54 (1.02–1.85) | 0.952 | 0.479 | 0.681 | |

| 8 | 0.81 (0.57–1.14) | 0.84 (0.69–1.05) | 0.88 (0.80–1.12) | 0.952 | 0.582 | 0.681 | |

| 9 | 2.23 (1.85–2.58) | 2.00 (1.72–2.29) | 1.79 (1.71–2.05) | 0.455 | 0.087 | 0.681 | |

| 10 | 0.92 (0.68–1.33) | 0.86 (0.77–1.01) | 1.20 (1.02–1.22) | 0.952 | 0.479 | 0.091 | |

| 11 | 1.46 (1.03–1.95) | 1.51 (1.14–1.81) | 1.27 (1.18–1.89) | 1.000 | 0.932 | 1.000 | |

| 12 | 5.37 (4.39–6.64) | 6.94 (5.58–9.50) | 8.49 (8.20–13.13) | 0.007 | 0.020 | 0.681 | |

| 13 | 3.97 (2.78–5.01) | 5.73 (3.95–8.44) | 8.85 (4.55–13.91) | 0.007 | 0.020 | 0.681 | |

| D5 Full-term (n = 35) Very preterm (n = 32) Extremely preterm (n = 13) | 1 | 2.38 (1.94–3.07) | 2.02 (1.69–3.03) | 2.41 (1.87–3.55) | 0.525 | 0.991 | 0.609 |

| 2 | 2.48 (2.16–2.86) | 2.07 (1.81–2.51) | 2.03 (1.93–3.79) | 0.264 | 0.991 | 0.598 | |

| 3 | 2.23 (1.84–2.32) | 2.08 (1.74–2.31) | 1.92 (1.75–2.45) | 0.656 | 0.991 | 0.950 | |

| 4 | 2.11 (1.84–2.46) | 2.02 (1.76–2.18) | 1.99 (1.58–2.22) | 0.264 | 0.982 | 0.950 | |

| 5 | 2.74 (2.41–3.05) | 2.56 (2.14–2.93) | 2.77 (2.42–3.21) | 0.431 | 0.991 | 0.445 | |

| 6 | 1.12 (0.95–1.35) | 1.07 (0.85–1.33) | 1.11 (1.05–1.24) | 0.495 | 0.991 | 0.598 | |

| 7 | 1.49 (1.25–1.76) | 1.29 (1.12–1.58) | 1.55 (1.27–1.67) | 0.264 | 0.991 | 0.483 | |

| 8 | 1.07 (0.71–1.24) | 0.82 (0.66–1.14) | 0.94 (0.74–1.13) | 0.329 | 0.991 | 0.598 | |

| 9 | 2.50 (2.14–2.91) | 1.89 (1.72–2.08) | 2.08 (1.92–2.34) | 0.013 | 0.074 | 0.445 | |

| 10 | 1.02 (0.83–1.34) | 0.85 (0.71–1.10) | 1.08 (0.80–1.23) | 0.264 | 0.991 | 0.483 | |

| 11 | 1.57 (1.28–2.21) | 1.39 (1.17–1.72) | 1.49 (1.30–1.75) | 0.264 | 0.991 | 0.483 | |

| 12 | 5.63 (4.60–6.27) | 5.47 (3.87–9.67) | 10.37 (6.84–13.65) | 0.597 | 0.013 | 0.445 | |

| 13 | 3.57 (2.85–4.83) | 3.64 (2.91–7.21) | 8.92 (5.98–13.66) | 0.525 | 0.013 | 0.445 | |

| D30 Full-term (n = 0) Very preterm (n = 26) Extremely preterm (n = 10) | 1 | N/A | 2.57 (1.96–2.94) | 2.11 (1.75–2.60) | N/A | N/A | 0.965 |

| 2 | N/A | 2.70 (2.03–3.20) | 2.47 (1.83–2.67) | N/A | N/A | 0.967 | |

| 3 | N/A | 2.23 (1.97–2.52) | 2.34 (1.92–2.45) | N/A | N/A | 0.967 | |

| 4 | N/A | 2.18 (2.03–2.57) | 2.30 (1.88–2.81) | N/A | N/A | 0.967 | |

| 5 | N/A | 3.08 (2.83–3.29) | 2.57 (2.39–2.83) | N/A | N/A | 0.104 | |

| 6 | N/A | 1.20 (1.06–1.49) | 1.16 (1.02–1.43) | N/A | N/A | 0.967 | |

| 7 | N/A | 1.45 (1.18–1.63) | 1.36 (1.25–1.48) | N/A | N/A | 0.967 | |

| 8 | N/A | 0.95 (0.77–1.10) | 1.16 (0.90–1.27) | N/A | N/A | 0.936 | |

| 9 | N/A | 2.22 (2.02–2.38) | 1.90 (1.81–2.02) | N/A | N/A | 0.104 | |

| 10 | N/A | 1.06 (0.83–1.27) | 1.05 (0.96–1.22) | N/A | N/A | 0.972 | |

| 11 | N/A | 1.57 (1.29–1.80) | 1.40 (1.37–1.77) | N/A | N/A | 0.972 | |

| 12 | N/A | 6.83 (5.58–13.06) | 9.41 (5.56–14.31) | N/A | N/A | 0.967 | |

| 13 | N/A | 5.74 (3.93–13.06) | 8.24 (4.56–14.46) | N/A | N/A | 0.967 |

| CpG | Day | Full-Term | Very Preterm | Extremely Preterm | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predicted Values | Beta | EP | p-Value * | Predicted Values | Beta | EP | p-Value * | Predicted Values | Beta | EP | p-Value * | ||

| D0 | 2.2840 | 0.2502 | 0.1255 | 0.1407 | 2.5276 | 0.0226 | 0.1212 | 0.8707 | 2.4159 | ||||

| CpG1 | D5 | 2.5342 | 2.5502 | 2.4147 | −0.0012 | 0.2485 | 0.9962 | ||||||

| D30 | 2.7844 | 2.5729 | 2.4135 | ||||||||||

| D0 | 2.2988 | 0.3901 | 0.1221 | 0.0195 | 2.7257 | −0.0437 | 0.1228 | 0.8549 | 2.7549 | ||||

| CpG2 | D5 | 2.6889 | 2.6820 | 2.7531 | −0.0017 | 0.2236 | 0.9962 | ||||||

| D30 | 3.0790 | 2.6383 | 2.7514 | ||||||||||

| D0 | 2.0700 | 0.0102 | 0.1010 | 0.9202 | 2.0492 | 0.0742 | 0.0639 | 0.4712 | 2.2538 | ||||

| CpG3 | D5 | 2.0802 | 2.1233 | 2.1974 | −0.0565 | 0.0839 | 0.9962 | ||||||

| D30 | 2.0904 | 2.1409 | 2.1409 | ||||||||||

| D0 | 2.1461 | 0.1095 | 0.0949 | 0.4167 | 2.7236 | 0.0756 | 0.0655 | 0.4712 | 2.1242 | ||||

| CpG4 | D5 | 2.2557 | 2.7991 | 2.2067 | 0.0825 | 0.1043 | 0.9962 | ||||||

| D30 | 2.3652 | 2.8747 | 2.2892 | ||||||||||

| D0 | 2.7022 | 0.1615 | 0.1628 | 0.4563 | 2.6272 | 0.1802 | 0.0676 | 0.1326 | 2.8331 | ||||

| CpG5 | D5 | 2.8637 | 2.8074 | 2.8410 | 0.0079 | 0.1271 | 0.9962 | ||||||

| D30 | 3.0252 | 2.9877 | 2.8488 | ||||||||||

| D0 | 0.9977 | 0.1300 | 0.1014 | 0.4082 | 1.0382 | 0.0744 | 0.0398 | 0.4349 | 1.2142 | ||||

| CpG6 | D5 | 1.1277 | 1.1126 | 1.2288 | 0.0146 | 0.0699 | 0.9962 | ||||||

| D30 | 1.2577 | 1.1870 | 1.2434 | ||||||||||

| D0 | 1.1674 | 0.2646 | 0.1226 | 0.1229 | 1.3246 | 0.0190 | 0.0481 | 0.8549 | 1.5331 | ||||

| CpG7 | D5 | 1.4320 | 1.3436 | 1.4474 | −0.0857 | 0.0787 | 0.9962 | ||||||

| D30 | 1.6966 | 1.3628 | 1.3617 | ||||||||||

| D0 | 0.7848 | 0.2572 | 0.1046 | 0.0828 | 0.8312 | 0.0537 | 0.0403 | 0.4712 | 0.9599 | ||||

| CpG8 | D5 | 1.0421 | 0.8850 | 0.9831 | 0.0232 | 0.0694 | 0.9962 | ||||||

| D30 | 1.2993 | 0.9387 | 1.0062 | ||||||||||

| D0 | 2.2437 | 0.3118 | 0.0903 | 0.0195 | 1.9935 | 0.0813 | 0.0565 | 0.4712 | 1.9423 | ||||

| CpG9 | D5 | 2.5555 | 2.0749 | 1.9525 | 0.0102 | 0.0796 | 0.9962 | ||||||

| D30 | 2.8673 | 2.1562 | 1.9626 | ||||||||||

| D0 | 0.9411 | 0.0702 | 0.1241 | 0.6796 | 0.8680 | 0.0673 | 0.0518 | 0.4712 | 1.1313 | ||||

| CpG10 | D5 | 1.0113 | 0.9353 | 1.0688 | −0.0626 | 0.0413 | 0.9962 | ||||||

| D30 | 1.0815 | 1.0027 | 1.0062 | ||||||||||

| D0 | 1.4758 | 0.2669 | 0.2067 | 0.4082 | 1.4357 | 0.0362 | 0.0576 | 0.7680 | 1.6116 | ||||

| CpG11 | D5 | 1.7427 | 1.4719 | 1.5489 | −0.0627 | 0.0748 | 0.9962 | ||||||

| D30 | 2.0096 | 1.4863 | 1.4863 | ||||||||||

| D0 | 6.0658 | 0.0852 | 0.2424 | 0.7879 | 7.9115 | −0.0367 | 0.2241 | 0.8707 | 10.5423 | ||||

| CpG12 | D5 | 6.1510 | 7.8748 | 10.7397 | 0.1974 | 0.6119 | 0.9962 | ||||||

| D30 | 6.2362 | 7.8381 | 10.9770 | ||||||||||

| D0 | 4.3856 | 0.2136 | 0.2259 | 0.4563 | 6.4420 | 0.2127 | 0.3016 | 0.7680 | 9.9944 | ||||

| CpG13 | D5 | 4.5992 | 6.6547 | 10.1319 | 0.1375 | 0.6956 | 0.9962 | ||||||

| D30 | 4.8128 | 6.8674 | 10.2693 | ||||||||||

| Total average methylation | D0 | 2.2632 | 0.2033 | 0.0471 | 0.0001 | 2.6559 | 0.0491 | 0.0555 | 0.3806 | 3.1807 | |||

| D5 | 2.4664 | 2.7050 | 3.1875 | 0.0068 | 0.1295 | 0.9583 | |||||||

| D30 | 2.6697 | 2.7541 | 3.1944 | ||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brasil, A.d.A.; Milone, L.T.V.; dos Santos, P.V.B.E.; Saide, S.C.A.d.O.; Paravidino, V.B.; Chalfun, G.; Ferreira, L.S.d.S.; Ferreira, M.B.C.; Ferreira, A.B.M.; de Farias, G.B.; et al. Prematurity and Epigenetic Regulation of SLC6A4: Longitudinal Insights from Birth to the First Month of Life. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2753. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13112753

Brasil AdA, Milone LTV, dos Santos PVBE, Saide SCAdO, Paravidino VB, Chalfun G, Ferreira LSdS, Ferreira MBC, Ferreira ABM, de Farias GB, et al. Prematurity and Epigenetic Regulation of SLC6A4: Longitudinal Insights from Birth to the First Month of Life. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(11):2753. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13112753

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrasil, Aline de Araújo, Leo Travassos Vieira Milone, Paulo Victor Barbosa Eleutério dos Santos, Stephanie Cristina Alves de Oliveira Saide, Vitor Barreto Paravidino, Georgia Chalfun, Letícia Santiago da Silva Ferreira, Mariana Berquó Carneiro Ferreira, Anna Beatriz Muniz Ferreira, Geovanna Barroso de Farias, and et al. 2025. "Prematurity and Epigenetic Regulation of SLC6A4: Longitudinal Insights from Birth to the First Month of Life" Biomedicines 13, no. 11: 2753. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13112753

APA StyleBrasil, A. d. A., Milone, L. T. V., dos Santos, P. V. B. E., Saide, S. C. A. d. O., Paravidino, V. B., Chalfun, G., Ferreira, L. S. d. S., Ferreira, M. B. C., Ferreira, A. B. M., de Farias, G. B., Robaina, J. R., de Oliveira, M. B. G., de Magalhães-Barbosa, M. C., Prata-Barbosa, A., & da Cunha, A. J. L. A. (2025). Prematurity and Epigenetic Regulation of SLC6A4: Longitudinal Insights from Birth to the First Month of Life. Biomedicines, 13(11), 2753. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13112753