L-Dopa Comparably Improves Gait and Limb Movements in Parkinson’s Disease: A Wearable Sensor Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects and Clinical Evaluation

2.2. Experimental Procedures

2.3. Wearable Sensors and Instrumental Outcome Measures

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Features

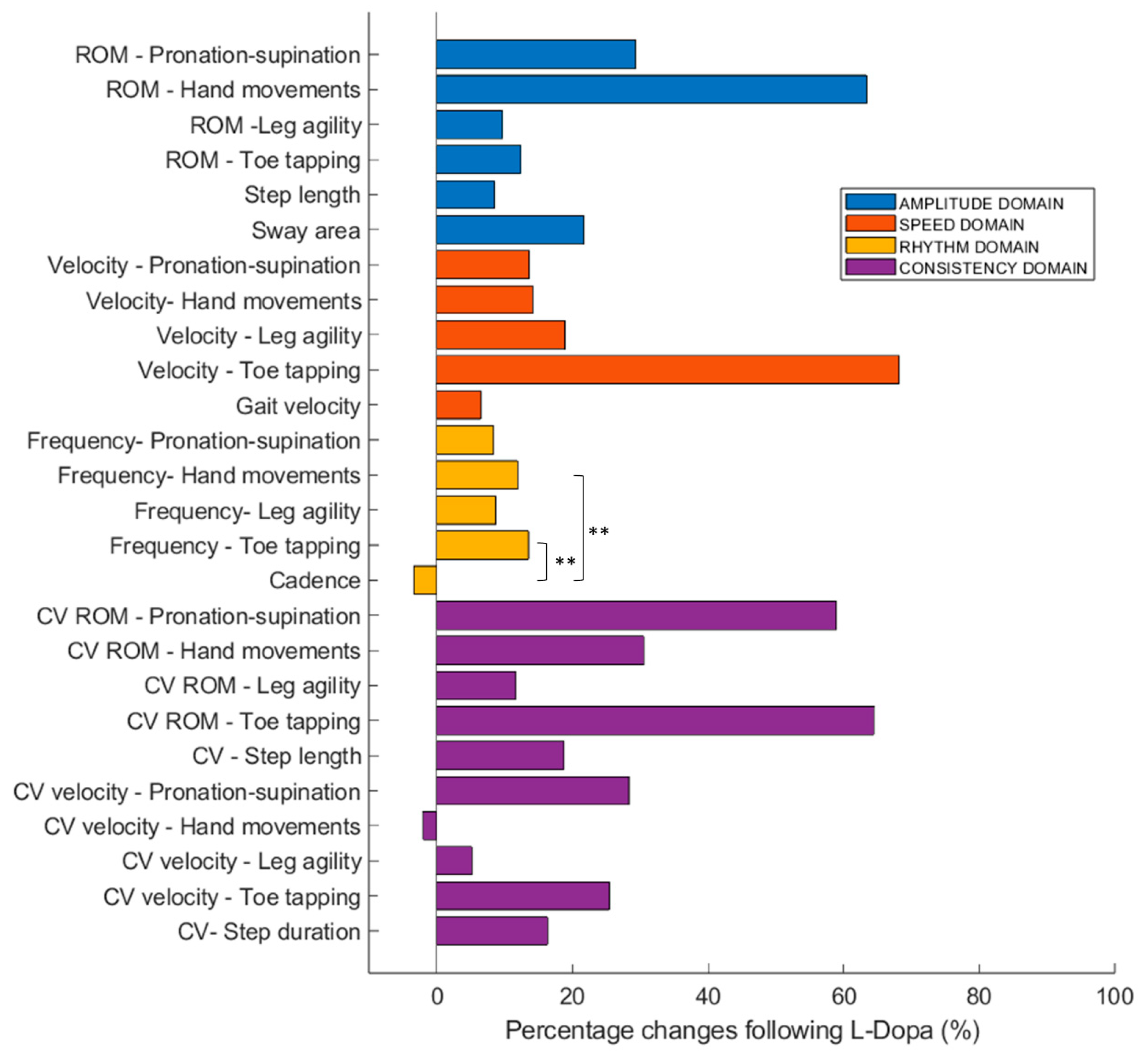

3.2. Sensor-Derived Measures

3.3. Clinical-Behavioral Correlations

4. Discussion

4.1. L-Dopa Comparably Improves Gait and Limb Movements in PD

4.2. Gait as a Clinical Biomarker of Disease State

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CV | Coefficient of Variation |

| FAB | Frontal Assessment Battery |

| IMU | Inertial Measurement Unit |

| LEDD | L-Dopa Equivalent Daily Dose |

| MDS-UPDRS | Movement Disorder Society—Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale |

| MoCA | Montreal Cognitive Assessment |

| PD | Parkinson’s Disease |

| ROM | Range of Motion |

| STROBE | Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology |

References

- Tanner, C.M.; Ostrem, J.L. Parkinson’s Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 442–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aradi, S.D.; Hauser, R.A. Medical Management and Prevention of Motor Complications in Parkinson’s Disease. Neurotherapeutics 2020, 17, 1339–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regensburger, M.; Csoti, I.; Jost, W.H.; Kohl, Z.; Lorenzl, S.; Pedrosa, D.J.; Lingor, P. Motor and Non-Motor Fluctuations in Parkinson’s Disease: The Knowns and Unknowns of Current Therapeutic Approaches. J. Neural Transm. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonini, A.; Martinez-Martin, P.; Chaudhuri, R.K.; Merello, M.; Hauser, R.; Katzenschlager, R.; Odin, P.; Stacy, M.; Stocchi, F.; Poewe, W.; et al. Wearing-off Scales in Parkinson’s Disease: Critique and Recommendations. Mov. Disord. 2011, 26, 2169–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amanzio, M.; Monteverdi, S.; Giordano, A.; Soliveri, P.; Filippi, P.; Geminiani, G. Impaired Awareness of Movement Disorders in Parkinson’s Disease. Brain Cogn. 2010, 72, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papapetropoulos, S.S. Patient Diaries as a Clinical Endpoint in Parkinson’s Disease Clinical Trials. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2012, 18, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, C.; Rouaud, T.; Grabli, D.; Benatru, I.; Remy, P.; Marques, A.-R.; Drapier, S.; Mariani, L.-L.; Roze, E.; Devos, D.; et al. Overview on Wearable Sensors for the Management of Parkinson’s Disease. npj Park. Dis. 2023, 9, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zampogna, A.; Manoni, A.; Asci, F.; Liguori, C.; Irrera, F.; Suppa, A. Shedding Light on Nocturnal Movements in Parkinson’s Disease: Evidence from Wearable Technologies. Sensors 2020, 20, 5171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zampogna, A.; Mileti, I.; Palermo, E.; Celletti, C.; Paoloni, M.; Manoni, A.; Mazzetta, I.; Dalla Costa, G.; Pérez-López, C.; Camerota, F.; et al. Fifteen Years of Wireless Sensors for Balance Assessment in Neurological Disorders. Sensors 2020, 20, 3247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, M.; Lazzaro, G.D.; Errico, V.; Pisani, A.; Giannini, F.; Saggio, G. The Impact of Wearable Electronics in Assessing the Effectiveness of Levodopa Treatment in Parkinson’s Disease. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2022, 26, 2920–2928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobo, P.; Morais, P.; Murray, P.; Vilaça, J.L. Trends and Innovations in Wearable Technology for Motor Rehabilitation, Prediction, and Monitoring: A Comprehensive Review. Sensors 2024, 24, 7973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rast, F.M.; Labruyère, R. Systematic Review on the Application of Wearable Inertial Sensors to Quantify Everyday Life Motor Activity in People with Mobility Impairments. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2020, 17, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Martín, D.; Pérez-López, C. Commercial Symptom Monitoring Devices in Parkinson’s Disease: Benefits, Limitations, and Trends. Front. Neurol. 2024, 15, 1470928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zampogna, A.; Borzì, L.; Rinaldi, D.; Artusi, C.A.; Imbalzano, G.; Patera, M.; Lopiano, L.; Pontieri, F.; Olmo, G.; Suppa, A. Unveiling the Unpredictable in Parkinson’s Disease: Sensor-Based Monitoring of Dyskinesias and Freezing of Gait in Daily Life. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zampogna, A.; Borzì, L.; Soares, C.; Demrozi, F. Editorial: High-Tech Personalized Healthcare in Movement Disorders. Front. Neurol. 2024, 15, 1452612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, S.H.; Soangra, R.; Frames, C.W.; Lockhart, T.E. Three Days Monitoring of Activities of Daily Living among Young Healthy Adults and Parkinson’s Disease Patients. Biomed. Sci. Instrum. 2021, 57, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, M.; Afshari, M.; Almeida, Q.; Amundsen-Huffmaster, S.; Balfany, K.; Camicioli, R.; Christiansen, C.; Dale, M.L.; Dibble, L.E.; Earhart, G.M.; et al. Digital Gait Biomarkers in Parkinson’s Disease: Susceptibility/Risk, Progression, Response to Exercise, and Prognosis. npj Park. Dis. 2025, 11, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Filippo, F.; De Biasi, G.; Russo, M.; Ricciardi, C.; Pisani, N.; Volzone, A.; Aiello, M.; Cuoco, S.; Calabrese, M.; Romano, M.; et al. Dual-Task-Related Gait Patterns as Possible Marker of Precocious and Subclinical Cognitive Alterations in Parkinson Disease. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 3371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Din, S.; Godfrey, A.; Mazzà, C.; Lord, S.; Rochester, L. Free-Living Monitoring of Parkinson’s Disease: Lessons from the Field. Mov. Disord. 2016, 31, 1293–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raschka, T.; To, J.; Hähnel, T.; Sapienza, S.; Ibrahim, A.; Glaab, E.; Gaßner, H.; Steidl, R.; Winkler, J.; Corvol, J.-C.; et al. Objective Monitoring of Motor Symptom Severity and Their Progression in Parkinson’s Disease Using a Digital Gait Device. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 25541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suppa, A.; Kita, A.; Leodori, G.; Zampogna, A.; Nicolini, E.; Lorenzi, P.; Rao, R.; Irrera, F. L-DOPA and Freezing of Gait in Parkinson’s Disease: Objective Assessment through a Wearable Wireless System. Front. Neurol. 2017, 8, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtze, C.; Nutt, J.G.; Carlson-Kuhta, P.; Mancini, M.; Horak, F.B. Levodopa Is a Double-Edged Sword for Balance and Gait in People with Parkinson’s Disease. Mov. Disord. 2015, 30, 1361–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vila, M.H.; Pérez, R.; Mollinedo, I.; Cancela, J.M. Analysis of Gait for Disease Stage in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brognara, L.; Palumbo, P.; Grimm, B.; Palmerini, L. Assessing Gait in Parkinson’s Disease Using Wearable Motion Sensors: A Systematic Review. Diseases 2019, 7, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marano, M.; Tinkhauser, G.; Anzini, G.; Leogrande, G.; Ricciuti, R.; Paniccia, M.; Belli, A.; Pierleoni, P.; Di Lazzaro, V.; Raggiunto, S. Subthalamic Beta Power and Gait in Parkinson’s Disease during Unsupervised Remote Monitoring. Park. Relat. Disord. 2025, 6, 107903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: Guidelines for Reporting Observational Studies. Lancet 2007, 370, 1453–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhidayasiri, R.; Tarsy, D. (Eds.) Parkinson’s Disease: Hoehn and Yahr Scale. In Movement Disorders: A Video Atlas; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 4–5. ISBN 978-1-60327-426-5. [Google Scholar]

- Dalrymple-Alford, J.C.; MacAskill, M.R.; Nakas, C.T.; Livingston, L.; Graham, C.; Crucian, G.P.; Melzer, T.R.; Kirwan, J.; Keenan, R.; Wells, S.; et al. The MoCA. Neurology 2010, 75, 1717–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monaghan, A.S.; Ragothaman, A.; Harker, G.R.; Carlson-Kuhta, P.; Horak, F.B.; Peterson, D.S. Freezing of Gait in Parkinson’s Disease: Implications for Dual-Task Walking. J. Park. Dis. 2023, 13, 1035–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bezdicek, O.; Růžička, F.; Fendrych Mazancova, A.; Roth, J.; Dušek, P.; Mueller, K.; Růžička, E.; Jech, R. Frontal Assessment Battery in Parkinson’s Disease: Validity and Morphological Correlates. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2017, 23, 675–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucas McKay, J.; Goldstein, F.C.; Sommerfeld, B.; Bernhard, D.; Perez Parra, S.; Factor, S.A. Freezing of Gait Can Persist after an Acute Levodopa Challenge in Parkinson’s Disease. npj Park. Dis. 2019, 5, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbri, M.; Coelho, M.; Abreu, D.; Guedes, L.C.; Rosa, M.M.; Costa, N.; Antonini, A.; Ferreira, J.J. Do Patients with Late-Stage Parkinson’s Disease Still Respond to Levodopa? Park. Relat. Disord. 2016, 26, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saranza, G.; Lang, A.E. Levodopa Challenge Test: Indications, Protocol, and Guide. J. Neurol. 2021, 268, 3135–3143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, C.L.; Stowe, R.; Patel, S.; Rick, C.; Gray, R.; Clarke, C.E. Systematic Review of Levodopa Dose Equivalency Reporting in Parkinson’s Disease. Mov. Disord. 2010, 25, 2649–2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saggio, G.; Tombolini, F.; Ruggiero, A. Technology-Based Complex Motor Tasks Assessment: A 6-DOF Inertial-Based System Versus a Gold-Standard Optoelectronic-Based One. IEEE Sens. J. 2021, 21, 1616–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, M.; Terribili, M.; Giannini, F.; Errico, V.; Pallotti, A.; Galasso, C.; Tomasello, L.; Sias, S.; Saggio, G. Wearable-Based Electronics to Objectively Support Diagnosis of Motor Impairments in School-Aged Children. J. Biomech. 2019, 83, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwak, S.; Park, S.-H. Normality Test in Clinical Research. J. Rheum. Dis. 2019, 26, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, M.R.; Fillyaw, M.J.; Thompson, W.D. The Use and Interpretation of the Friedman Test in the Analysis of Ordinal-Scale Data in Repeated Measures Designs. Physiother. Res. Int. 1996, 1, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedgwick, P. Spearman’s Rank Correlation Coefficient. BMJ 2014, 349, g7327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Loon, W. The Power of the Benjamini-Hochberg Procedure. Master’s Thesis, Leiden University, Leiden, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolcheva, T.; Pagano, G.; Pross, N.; Simuni, T.; Marek, K.; Postuma, R.B.; Pavese, N.; Stocchi, F.; Seppi, K.; Monnet, A.; et al. A Phase 2b, Multicenter, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of Intravenous Prasinezumab in Early-Stage Parkinson’s Disease (PADOVA): Rationale, Design, and Baseline Data. Park. Relat. Disord. 2025, 132, 107257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lazzaro, G.; Ricci, M.; Saggio, G.; Costantini, G.; Schirinzi, T.; Alwardat, M.; Pietrosanti, L.; Patera, M.; Scalise, S.; Giannini, F.; et al. Technology-Based Therapy-Response and Prognostic Biomarkers in a Prospective Study of a de Novo Parkinson’s Disease Cohort. npj Park. Dis. 2021, 7, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pringsheim, T.; Day, G.S.; Smith, D.B.; Rae-Grant, A.; Licking, N.; Armstrong, M.J.; de Bie, R.M.A.; Roze, E.; Miyasaki, J.M.; Hauser, R.A.; et al. Dopaminergic Therapy for Motor Symptoms in Early Parkinson Disease Practice Guideline Summary. Neurology 2021, 97, 942–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stinear, C.M.; Byblow, W.D. Predicting and Accelerating Motor Recovery after Stroke. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2014, 27, 624–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinu, K.; Nagano-Saito, A.; Fogel, S.; Monchi, O. Asymmetrical Effect of Levodopa on the Neural Activity of Motor Regions in PD. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e111600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, M.H.; Simieli, L.; Rietdyk, S.; Penedo, T.; Santinelli, F.B.; Barbieri, F.A. (A)Symmetry during Gait Initiation in People with Parkinson’s Disease: A Motor and Cortical Activity Exploratory Study. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2023, 15, 1142540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, K.J.M.; Singhal, A.; Leung, A.W.S. The Lateralized Effects of Parkinson’s Disease on Motor Imagery: Evidence from Mental Chronometry. Brain Cogn. 2024, 178, 106181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.L.; Dinesh, K.; Snyder, C.W.; Xiong, M.; Tarolli, C.G.; Sharma, S.; Dorsey, E.R.; Sharma, G. A Real-World Study of Wearable Sensors in Parkinson’s Disease. npj Park. Dis. 2021, 7, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monje, M.H.G.; Sánchez-Ferro, Á.; Pineda-Pardo, J.A.; Vela-Desojo, L.; Alonso-Frech, F.; Obeso, J.A. Motor Onset Topography and Progression in Parkinson’s Disease: The Upper Limb Is First. Mov. Disord. 2021, 36, 905–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halliday, G.; Hely, M.; Reid, W.; Morris, J. The Progression of Pathology in Longitudinally Followed Patients with Parkinson’s Disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2008, 115, 409–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryant, M.S.; Rintala, D.H.; Hou, J.G.; Lai, E.C.; Protas, E.J. Effects of Levodopa on Forward and Backward Gait Patterns in Persons with Parkinson’s Disease. NeuroRehabilitation 2011, 29, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasano, A.; Mazzoni, A.; Falotico, E. Reaching and Grasping Movements in Parkinson’s Disease: A Review. J. Park. Dis. 2022, 12, 1083–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maillet, A.; Krainik, A.; Debû, B.; Troprès, I.; Lagrange, C.; Thobois, S.; Pollak, P.; Pinto, S. Levodopa Effects on Hand and Speech Movements in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease: A fMRI Study. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e46541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Syeda, H.B.; Glover, A.; Pillai, L.; Kemp, A.S.; Spencer, H.; Lotia, M.; Larson-Prior, L.J.; Virmani, T. Amplitude Setting and Dopamine Response of Finger Tapping and Gait Are Related in Parkinson’s Disease. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 4180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinoda, Y.; Sugiuchi, Y.; Izawa, Y.; Hata, Y. Long Descending Motor Tract Axons and Their Control of Neck and Axial Muscles. Prog. Brain Res. 2006, 151, 527–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thijssen, E.; Makai-Bölöni, S.; van Brummelen, E.; den Heijer, J.; Yavuz, Y.; Doll, R.; Groeneveld, G.J. A Placebo-Controlled Study to Assess the Sensitivity of Finger Tapping to Medication Effects in Parkinson’s Disease. Mov. Disord. Clin. Pract. 2022, 9, 1074–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.H.; Mestre, T.A.; Fox, S.H.; Taati, B. Vision-Based Assessment of Parkinsonism and Levodopa-Induced Dyskinesia with Pose Estimation. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2018, 15, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, A.; Cantú, H.; Côté, J.N.; Nantel, J. Reaching and Stepping Respond Differently to Medication and Cueing in Parkinson’s Disease. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 24461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Workman, C.D.; Thrasher, T.A. The Influence of Dopaminergic Medication on Gait Automaticity in Parkinson’s Disease. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2019, 65, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herz, D.M.; Brown, P. Moving, Fast and Slow: Behavioural Insights into Bradykinesia in Parkinson’s Disease. Brain 2023, 146, 3576–3586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanardi, A.P.J.; da Silva, E.S.; Costa, R.R.; Passos-Monteiro, E.; dos Santos, I.O.; Kruel, L.F.M.; Peyré-Tartaruga, L.A. Gait Parameters of Parkinson’s Disease Compared with Healthy Controls: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramdhani, R.A.; Watts, J.; Kline, M.; Fitzpatrick, T.; Niethammer, M.; Khojandi, A. Differential Spatiotemporal Gait Effects with Frequency and Dopaminergic Modulation in STN-DBS. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2023, 15, 1206533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F.; Benarroch, E. What Is the Brainstem Control of Locomotion? Neurology 2022, 98, 446–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takakusaki, K.; Chiba, R.; Nozu, T.; Okumura, T. Brainstem Control of Locomotion and Muscle Tone with Special Reference to the Role of the Mesopontine Tegmentum and Medullary Reticulospinal Systems. J. Neural Transm. 2016, 123, 695–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, R.S.; Desmurget, M. Basal Ganglia Contributions to Motor Control: A Vigorous Tutor. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2010, 20, 704–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spraker, M.B.; Yu, H.; Corcos, D.M.; Vaillancourt, D.E. Role of Individual Basal Ganglia Nuclei in Force Amplitude Generation. J. Neurophysiol. 2007, 98, 821–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.H.; Patel, S.; Gavine, B.; Buchanan, T.; Bogdanovic, M.; Sarangmat, N.; Green, A.L.; Bloem, B.R.; FitzGerald, J.J.; Antoniades, C.A. Deep Brain Stimulation and Levodopa Affect Gait Variability in Parkinson Disease Differently. Neuromodulation Technol. Neural Interface 2023, 26, 382–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierleoni, P.; Raggiunto, S.; Belli, A.; Paniccia, M.; Bazgir, O.; Palma, L. A Single Wearable Sensor for Gait Analysis in Parkinson’s Disease: A Preliminary Study. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 5486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sica, M.; Tedesco, S.; Crowe, C.; Kenny, L.; Moore, K.; Timmons, S.; Barton, J.; O’Flynn, B.; Komaris, D.-S. Continuous Home Monitoring of Parkinson’s Disease Using Inertial Sensors: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0246528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- di Biase, L.; Di Santo, A.; Caminiti, M.L.; De Liso, A.; Shah, S.A.; Ricci, L.; Di Lazzaro, V. Gait Analysis in Parkinson’s Disease: An Overview of the Most Accurate Markers for Diagnosis and Symptoms Monitoring. Sensors 2020, 20, 3529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fay-Karmon, T.; Galor, N.; Heimler, B.; Zilka, A.; Bartsch, R.P.; Plotnik, M.; Hassin-Baer, S. Home-Based Monitoring of Persons with Advanced Parkinson’s Disease Using Smartwatch-Smartphone Technology. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.L.; Kangarloo, T.; Gong, Y.; Khachadourian, V.; Tracey, B.; Volfson, D.; Latzman, R.D.; Cosman, J.; Edgerton, J.; Anderson, D.; et al. Using a Smartwatch and Smartphone to Assess Early Parkinson’s Disease in the WATCH-PD Study over 12 Months. npj Park. Dis. 2024, 10, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farabolini, G.; Baldini, N.; Pagano, A.; Andrenelli, E.; Pepa, L.; Morone, G.; Ceravolo, M.G.; Capecci, M. Continuous Movement Monitoring at Home Through Wearable Devices: A Systematic Review. Sensors 2025, 25, 4889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Participants (N) | Age | Disease Duration | Hoehn and Yahr | MDS-UPDRS III | Clinical Phenotype | MoCA | FAB | LEDD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OFF | ON | ||||||||

| 14 Males 8 Females | 70.4 ± 7.9 | 3.9 ± 3.5 | 2.1 ± 0.5 | 30.8 ± 9.7 | 19.4 ± 10.1 | 13 AR 6 Trem 3 Mixed | 25.5 ± 3.4 | 15.4 ± 2.5 | 513.2 ± 226.8 |

| Motor Tasks | Movement Amplitude | Movement Speed | Movement Rhythm | Movement Consistency | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appendicular functions (more affected side) | Hand movements | ROM: 63.4 ± 154.9 | Vel: 14.1 ± 34.6 | Freq: 11.9 ± 17.1 | CV ROM: 30.5 ± 136.7 CV vel: −2.0 ± 43.7 |

| Hand pronation–supination | ROM: 29.3 ± 83.8 | Vel: 13.6 ± 64.1 | Freq: 8.4 ± 35.7 | CV ROM: 58.9 ± 234.7 CV vel: 28.3 ± 74.9 | |

| Toe tapping | ROM: 12.4 ± 65.4 | Vel: 68.2 ± 324.4 | Freq: 13.5 ± 21.1 | CV ROM: 64.4 ± 245.6 CV vel: 25.5 ± 89.0 | |

| Leg agility | ROM: 9.7 ± 102.8 | Vel: 18.9 ± 63.2 | Freq: 8.7 ± 26.7 | CV ROM: 11.7 ± 64.9 CV vel: 5.2 ± 31.9 | |

| Axial functions | Gait | Step length: 3.9 ± 11.1 | Step vel: 6.5 ± 16.5 | Cad: −3.4 ± 5.4 | CV step length: 18.7 ± 104.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zampogna, A.; Pietrosanti, L.; Saggio, G.; Patera, M.; Falletti, M.; Bellia, V.; Fattapposta, F.; Costantini, G.; Suppa, A. L-Dopa Comparably Improves Gait and Limb Movements in Parkinson’s Disease: A Wearable Sensor Analysis. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2727. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13112727

Zampogna A, Pietrosanti L, Saggio G, Patera M, Falletti M, Bellia V, Fattapposta F, Costantini G, Suppa A. L-Dopa Comparably Improves Gait and Limb Movements in Parkinson’s Disease: A Wearable Sensor Analysis. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(11):2727. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13112727

Chicago/Turabian StyleZampogna, Alessandro, Luca Pietrosanti, Giovanni Saggio, Martina Patera, Marco Falletti, Valentina Bellia, Francesco Fattapposta, Giovanni Costantini, and Antonio Suppa. 2025. "L-Dopa Comparably Improves Gait and Limb Movements in Parkinson’s Disease: A Wearable Sensor Analysis" Biomedicines 13, no. 11: 2727. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13112727

APA StyleZampogna, A., Pietrosanti, L., Saggio, G., Patera, M., Falletti, M., Bellia, V., Fattapposta, F., Costantini, G., & Suppa, A. (2025). L-Dopa Comparably Improves Gait and Limb Movements in Parkinson’s Disease: A Wearable Sensor Analysis. Biomedicines, 13(11), 2727. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13112727