Exosome-Based Proteomic Profiling for Biomarker Discovery in Pediatric Fabry Disease: Insights into Early Diagnosis Monitoring

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient and Specimen Information

2.2. Exosome Extraction and Detection

2.3. Exosomal Protein Analysis via Mass Spectrometry

2.4. Cell Culture

2.5. Immunofluorescence (IF)

2.6. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

2.7. Quantitative Reverse Transcription PCR (qPCR)

2.8. Bioinformatics Analysis

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Information

3.2. Renal and Cardiac Function in Fabry Patients

3.3. Correlation Analysis of Clinical Indicators

3.4. Exosome Characterization

3.5. Protein Analysis of Exosomes from FD and Control Groups

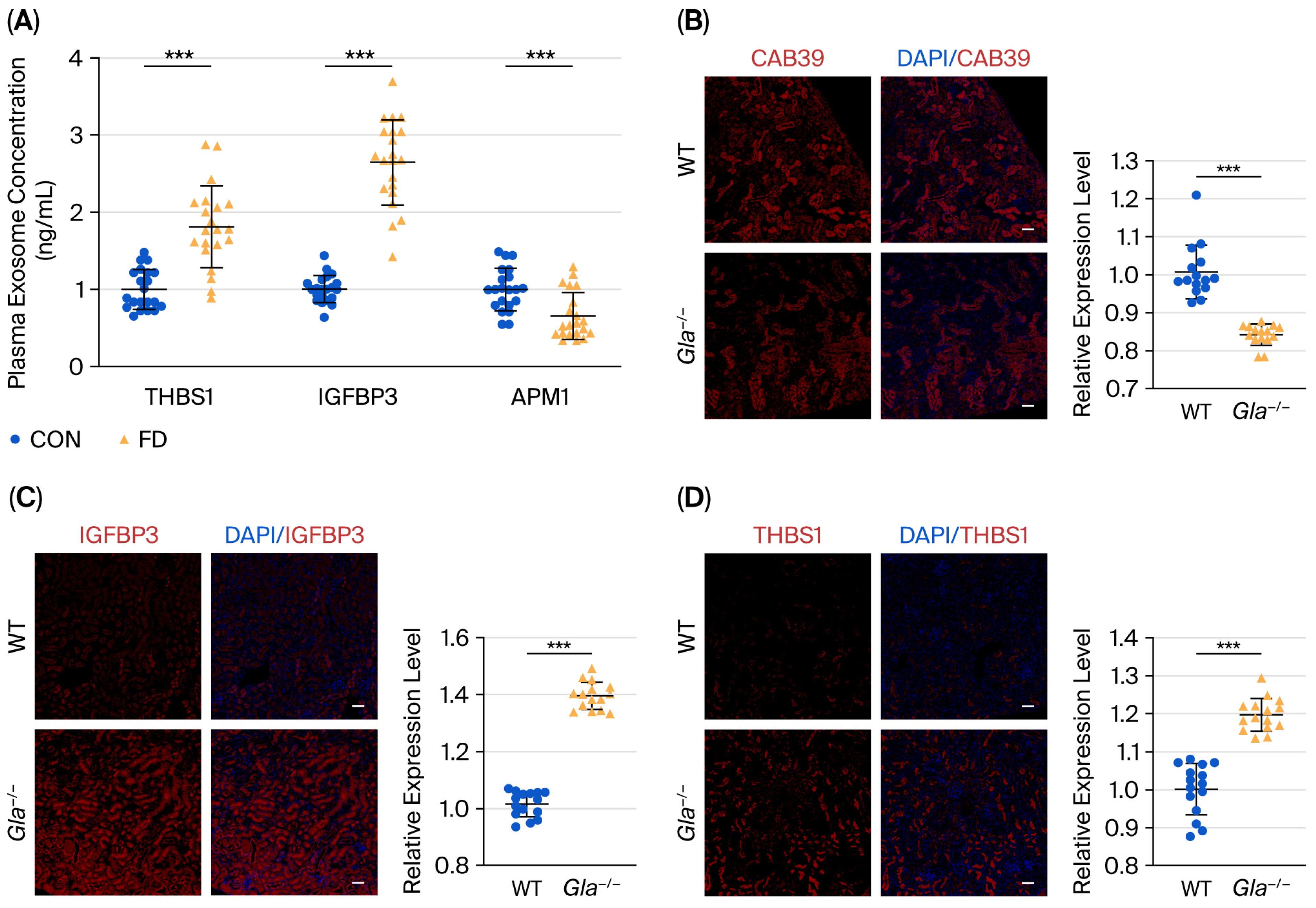

3.6. Validation of Differential Proteins

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FD | Fabry disease |

| α-Gal A | α-galactosidase A |

| GL-3 | globotriaosylceramide |

| Lyso-GL-3 | glycosphingolipids |

References

- Toyooka, K. Fabry disease. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2011, 24, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soloway, S.; Lister, D. Fabry’s Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borisch, C.; Thum, T.; Bär, C.; Hoepfner, J. Human in vitro models for Fabry disease: New paths for unravelling disease mechanisms and therapies. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenders, M.; Brand, E. Precision medicine in Fabry disease. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2021, 36, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponleitner, M.; Gatterer, C.; Bsteh, G.; Rath, J.; Altmann, P.; Berger, T.; Graf, S.; Sunder-Plassmann, G.; Rommer, P.S. Investigation of serum neurofilament light chain as a biomarker in Fabry disease. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 23033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuertes Kenneally, L.; García-Álvarez, M.I.; Feliu Rey, E.; García Barrios, A.; Climent-Payá, V. Fabry Disease Cardiomyopathy: A Review of the Role of Cardiac Imaging from Diagnosis to Treatment. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 23, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puspita, R.; Jusuf, A.A. Systematic review of exosomes derived from various stem cell sources: Function and therapeutic potential in disease modulation. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2025, 52, 842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Wang, W.; Li, N.; Garcia-Lezana, T.; Che, C.; Wang, X.; Losic, B.; Villanueva, A.; Cunningham, B.T. Digital-resolution and highly sensitive detection of multiple exosomal small RNAs by DNA toehold probe-based photonic resonator absorption microscopy. Talanta 2022, 241, 123256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.J.; Chau, Z.L.; Chen, S.Y.; Hill, J.J.; Korpany, K.V.; Liang, N.W.; Lin, L.H.; Lin, Y.H.; Liu, J.K.; Liu, Y.C.; et al. Exosome Processing and Characterization Approaches for Research and Technology Development. Adv. Sci. Weinh. 2022, 9, e2103222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonetta, I.; Tuttolomondo, A.; Daidone, M.; Pinto, A. Biomarkers in Anderson-Fabry Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieroni, M.; Namdar, M.; Olivotto, I.; Desnick, R.J. Anderson-Fabry disease management: Role of the cardiologist. Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, 1395–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkin, R.J.; Laney, D.; Kazemi, S.; Walter, A. Fabry disease in females: Organ involvement and clinical outcomes compared with the general population (103/150 characters). Orphanet. J. Rare Dis. 2025, 20, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riccio, E.; Pisani, A. Real-World Migalastat Use in Fabry Disease: Comparative Insights from the Pisani and Hughes Studies. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2025, 48, e70080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weissman, D.; Dudek, J.; Sequeira, V.; Maack, C. Fabry Disease: Cardiac Implications and Molecular Mechanisms. Curr. Heart Fail Rep. 2024, 21, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burlina, A.; Brand, E.; Hughes, D.; Kantola, I.; Krämer, J.; Nowak, A.; Tøndel, C.; Wanner, C.; Spada, M. An expert consensus on the recommendations for the use of biomarkers in Fabry disease. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2023, 139, 107585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsborne, C.; Black, N.; Naish, J.H.; Woolfson, P.; Reid, A.B.; Schmitt, M.; Jovanovic, A.; Miller, C.A. Disease-specific therapy for the treatment of the cardiovascular manifestations of Fabry disease: A systematic review. Heart 2023, 110, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellaway, C. Paediatric Fabry disease. Transl. Pediatr. 2016, 5, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruyama, H.; Miyata, K.; Mikame, M.; Taguchi, A.; Guili, C.; Shimura, M.; Murayama, K.; Inoue, T.; Yamamoto, S.; Sugimura, K.; et al. Effectiveness of plasma lyso-Gb3 as a biomarker for selecting high-risk patients with Fabry disease from multispecialty clinics for genetic analysis. Genet. Med. 2019, 21, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.H.; Wang, X.F.; Wu, X.; Yan, P.; Liu, Q.; Wu, T.; Duan, S.B. Differential renal proteomics analysis in a novel rat model of iodinated contrast-induced acute kidney injury. Ren. Fail. 2023, 45, 2178821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimaru, T.; Mori, T.; Chiga, M.; Mandai, S.; Kikuchi, H.; Ando, F.; Mori, Y.; Susa, K.; Nakano, Y.; Shoji, T.; et al. Genetic Diagnosis of Adult Hemodialysis Patients with Unknown Etiology. Kidney Int. Rep. 2024, 9, 994–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, M.; Lian, D.; Wu, M.; Zhou, Y.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, W.; Yang, Y.; Li, R.; Chen, H.; et al. Isoliensinine Attenuates Renal Fibrosis and Inhibits TGF-β1/Smad2/3 Signaling Pathway in Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2023, 17, 2749–2762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julovi, S.M.; Trinh, K.; Robertson, H.; Xu, C.; Minhas, N.; Viswanathan, S.; Patrick, E.; Horowitz, J.D.; Meijles, D.N.; Rogers, N.M. Thrombospondin-1 Drives Cardiac Remodeling in Chronic Kidney Disease. JACC Basic Transl. Sci. 2024, 9, 607–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, T.H.; Gitterman, D.P.; Lavin, D.P.; Lomax-Browne, H.J.; Hiemeyer, E.C.; Moran, L.B.; Boroviak, K.; Cook, H.T.; Gilmore, A.C.; Mandwie, M.; et al. Gain-of-function factor H-related 5 protein impairs glomerular complement regulation resulting in kidney damage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2022722118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biddeci, G.; Spinelli, G.; Colomba, P.; Duro, G.; Giacalone, I.; Di Blasi, F. Fabry Disease Beyond Storage: The Role of Inflammation in Disease Progression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaipov, A.; Makhammajanov, Z.; Dauyey, Z.; Markhametova, Z.; Mussina, K.; Nogaibayeva, A.; Kozina, L.; Auganova, D.; Tarlykov, P.; Bukasov, R.; et al. Urinary Protein Profiling for Potential Biomarkers of Chronic Kidney Disease: A Pilot Study. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, H.M.; Liang, X.; Xin, J.; Lu, Y.; Cai, Q.; Shi, D.; Ren, K.; Li, J.; Chen, Q.; Li, J.; et al. Thrombospondin 1 enhances systemic inflammation and disease severity in acute-on-chronic liver failure. BMC Med. 2024, 22, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kwak, H.B. Role of adiponectin in metabolic and cardiovascular disease. J. Exerc. Rehabil. 2014, 10, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, R.; Von Ende, A.; Schmidt, L.E.; Yin, X.; Hill, M.; Hughes, A.D.; Pechlaner, R.; Willeit, J.; Kiechl, S.; Watkins, H.; et al. Apolipoprotein Proteomics for Residual Lipid-Related Risk in Coronary Heart Disease. Circ. Res. 2023, 132, 452–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jønck, S.; Adamsen, M.L.; Rasmussen, I.E.; Lytzen, A.A.; Løk, M.; Vonsild Lund, M.A.; Dreyer, L.; Jørgensen, P.G.; Vejlstrup, N.; Køber, L.; et al. IL-6 Inhibitors and TNF Inhibitors: Impact on Exercise-induced Cardiac Adaptations in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. JACC Basic Transl. Sci. 2025, 10, 551–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, K.; Maeda, N.; Sonoda, M.; Ohashi, K.; Hibuse, T.; Nishizawa, H.; Nishida, M.; Hiuge, A.; Kurata, A.; Kihara, S.; et al. Adiponectin protects against angiotensin II-induced cardiac fibrosis through activation of PPAR-α. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2008, 28, 863–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, W.; Zhu, M.; Wen, X.; Jin, J.; Wang, H.; Lv, D.; Zhao, S.; Wu, X.; Jiao, J. Myokines and Biomarkers of Frailty in Older Inpatients with Undernutrition: A Prospective Study. J. Frailty Aging 2024, 13, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mecatti, G.C.; Messias, M.C.F.; de Oliveira Carvalho, P. Lipidomic profile and candidate biomarkers in septic patients. Lipids Health Dis. 2020, 19, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.J.; Choi, S.; Cheon, D.H.; Kim, K.Y.; Cheon, E.J.; Ann, S.J.; Noh, H.M.; Park, S.; Kang, S.M.; Choi, D.; et al. Effect of two lipid-lowering strategies on high-density lipoprotein function and some HDL-related proteins: A randomized clinical trial. Lipids Health Dis. 2017, 16, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botoseneanu, A.; Markwardt, S.; Quiñones, A.R. Multimorbidity and Functional Disability among Older Adults: The Role of Inflammation and Glycemic Status—An Observational Longitudinal Study. Gerontology 2023, 69, 826–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Diagnosis Age | Diagnosis Years (Years) | Gender | GLA Gene Mutation | Exon | α-Gal A Mutation | Mutation Origin | ACMG Classification * | α-Gal A Levels ☆ | Lyso-GL-3 Levels ▲ | Acroparesthesia | Hypohidrosis or Anhidrosis | Skin Vascular Keratomas | Gastrointestinal Symptoms | Screening Method | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 14Y | 3 | Male | c.424T>C | E3 | p.Cys142Arg | Mother | Pathogenic | 0.32 | 80.45 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | High-risk screening |

| 2 | 16Y9M | - | Female | c.335G>A | E2 | p.vArg112His | Father | Pathogenic | 2.1 | 0.55 | No | No | No | No | Familial screening |

| 3 | 6Y | - | Female | c.335G>A | E2 | p.Arg112His | Father | Pathogenic | 1.31 | 0.51 | No | No | No | No | Familial screening |

| 4 | 11Y10M | 6 | Male | c.644A>G | E5 | p.Asn215Ser | Mother | Pathogenic | 0.6 | 7.01 | No | Yes | No | No | High-risk screening |

| 5 | 11Y5M | 1 | Male | c.140G>A | E1 | p.Trp47Ter | Mother | Likely pathogenic | 0.4 | 92.98 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | High-risk screening |

| 6 | 13Y6M | 1 | Male | c.3G>A | E1 | p.Met1? | Spontaneous mutation | Likely pathogenic | 0.34 | 74.02 | Yes | Yes | No | No | High-risk screening |

| 7 | 9Y9M | 1 | Male | c.100A>G | E1 | p.Asn34His | Mother | Pathogenic | 0.33 | 64.05 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Familial screening |

| 8 | 9Y9M | 0.7 | Male | c.100A>G | E1 | p.Asn34His | Mother | Pathogenic | 0.4 | 65.03 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Familial screening |

| 9 | 11Y11M | - | Female | c.100A>G | E1 | p.Asn34His | Mother | Pathogenic | 1.64 | 2.77 | No | No | No | No | Familial screening |

| 10 | 8Y1M | 1 | Male | c.776C>T | E5 | p.Pro259Leu | Mother | VUS | 0.35 | 75.16 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Familial screening |

| 11 | 12Y9M | 5 | Male | c.334C>T | E2 | p.Arg112Cys | Mother | Pathogenic | 0.35 | 59.73 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | High-risk screening |

| 12 | 10Y10M | 1.5 | Male | c.334C>T | E2 | p.Arg112Cys | Mother | Pathogenic | 0.45 | 69.44 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Familial screening |

| 13 | 8Y2M | 0.7 | Male | c.782G>T | E5 | p.Gly261Val | Mother | Pathogenic | 0.28 | 71.33 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | High-risk screening |

| 14 | 7Y11M | - | Female | c.782G>T | E5 | p.Gly261Val | Mother | Pathogenic | 1.6 | 4.52 | No | Yes | No | No | Familial screening |

| 15 | 12Y9M | 4.1 | Male | c.72G>A | E1 | p.Trp24Ter | Mother | Pathogenic | 0.32 | 115.63 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | High-risk screening |

| 16 | 9Y8M | 1 | Female | c.640–801G>A | I4 | - | Father | Pathogenic | 3.7 | 1.69 | Yes | No | No | Yes | High-risk screening |

| 17 | 13Y9M | 2 | Male | C.486 G>A | E3 | p.Trp162 Ter | Mother | Pathogenic | 0.67 | 72.6 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Familial screening |

| 18 | 17Y | 7 | Male | c.1072_1074delGAG | E7 | p.Glu358del | Mother | Pathogenic | 0.26 | 65.57 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High-risk screening |

| 19 | 8Y6M | 1 | Male | c.454_456dupTAC | E3 | p.Tyr152dup | Mother | Pathogenic | 0.86 | 66.96 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Familial screening |

| 20 | 10Y10M | - | Female | c.1197G>A | E1 | p.Trp399Ter | Father | Pathogenic | 1.49 | 3.73 | Yes | No | No | No | Familial screening |

| 21 | 8Y6M | - | Female | c.187T>C | E1 | p.Cys63Arg | Father | Likely pathogenic | 0.49 | 11.96 | No | No | No | No | Familial screening |

| Scr (μmol/L) | eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | UACR (mg/g·Cr) | RBC/HPF | 24 h UP (mg) | cTnI (ng/mL) | LVMI (g/m2.7) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 85 | 74.7 | 26.7 | >200 | 209 | 0.09 | 44.1 |

| 2 | 73 | 82.0 | 10.3 | 6 | 81.2 | 0.01 | 39.4 |

| 3 | 51 | 88.7 | 8.7 | 4 | 46.3 | 0.01 | 40.4 |

| 4 | 51 | 114.5 | 9.6 | 6 | 159.9 | 0.08 | 42.3 |

| 5 | 35 | 152.3 | 22.2 | 6 | 81.8 | 0.05 | 42 |

| 6 | 31 | 175.4 | 11.4 | 5 | 54.1 | 0.06 | 32.2 |

| 7 | 37 | 127.3 | 10.6 | 2 | 81.6 | 0.02 | 39.5 |

| 8 | 46 | 123.8 | 9.3 | 2 | 36.2 | 0.01 | 34 |

| 9 | 38 | 154.6 | 8.3 | 0 | 41.8 | 0.04 | 26.5 |

| 10 | 30 | 176.4 | 30.3 | 7 | 101.8 | 0.05 | 51.7 |

| 11 | 46 | 119.0 | 7.7 | 4 | 91.9 | 0.15 | 39.6 |

| 12 | 34 | 141.7 | 7.9 | 4 | 80.3 | 0.03 | 51 |

| 13 | 34 | 138.4 | 8.21 | 4 | 65.2 | 0.04 | 43.3 |

| 14 | 38 | 135.4 | 9.0 | 0 | 74.5 | 0.01 | 26.9 |

| 15 | 56 | 102.3 | 3.9 | 0 | 83.4 | 0.07 | 30.8 |

| 16 | 38 | 125.8 | 2.7 | 0 | 61.1 | 0.08 | 24.7 |

| 17 | 54 | 105.4 | 2.2 | 0 | 106.1 | 0.02 | 52.3 |

| 18 | 64 | 103.2 | 19.0 | 0 | 86.7 | 0.19 | 26.9 |

| 19 | 38 | 142.2 | 6.0 | 0 | 104.8 | 0.01 | 40.1 |

| 20 | 38 | 152.7 | 5.4 | 0 | 79.6 | 0.06 | 25.5 |

| 21 | 41 | 119.3 | 10.6 | 0 | 144.1 | 0.13 | 23.6 |

| Variable | Group | Mean ± SD | Mean Difference (95% CI) | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α-GalA (μmol/L/h) | Male | 0.36 ± 0.03 | −1.41 (−2.31 to −0.51) | −3.82 | 0.01 ** |

| Female | 1.76 ± 0.98 | ||||

| Lyso-GL-3 (ng/mL) | Male | 73.06 ± 11.40 | 69.38 (56.03 to 82.74) | 12.71 | 0.00 ** |

| Female | 3.68 ± 3.96 | ||||

| cTnI (ng/mL) | Male | 0.05 ± 0.03 | 0.00 (−0.06 to −0.06) | 0.11 | 0.91 |

| Female | 0.05 ± 0.05 | ||||

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | Male | 134.91 ± 36.25 | 12.27 (−15.39 to −39.93) | 1.09 | 0.32 |

| Female | 122.64 ± 28.61 | ||||

| LVMI (g/m2.7) | Male | 40.83 ± 6.52 | 11.26 (2.92 to 19.60) | 3.30 | 0.02 * |

| Female | 29.57 ± 7.15 |

| Variable | α-GalA | Lyso-GL-3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | p | r | p | |

| α-GalA (μmoL/L/h) | - | - | −0.70 | 0.00 ** |

| Lyso-GL-3 (ng/mL) | −0.70 | 0.00 ** | - | - |

| cTnI (ng/mL) | −0.20 | 0.38 | 0.09 | 0.70 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | −0.08 | 0.75 | 0.11 | 0.65 |

| LVMI (g/m2.7) | −0.42 | 0.06 | 0.44 * | 0.04 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lu, Z.; Xia, Y.; Wang, B.; Jiang, P.; Mao, J. Exosome-Based Proteomic Profiling for Biomarker Discovery in Pediatric Fabry Disease: Insights into Early Diagnosis Monitoring. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2598. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13112598

Lu Z, Xia Y, Wang B, Jiang P, Mao J. Exosome-Based Proteomic Profiling for Biomarker Discovery in Pediatric Fabry Disease: Insights into Early Diagnosis Monitoring. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(11):2598. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13112598

Chicago/Turabian StyleLu, Zhihong, Yu Xia, Bingying Wang, Pingping Jiang, and Jianhua Mao. 2025. "Exosome-Based Proteomic Profiling for Biomarker Discovery in Pediatric Fabry Disease: Insights into Early Diagnosis Monitoring" Biomedicines 13, no. 11: 2598. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13112598

APA StyleLu, Z., Xia, Y., Wang, B., Jiang, P., & Mao, J. (2025). Exosome-Based Proteomic Profiling for Biomarker Discovery in Pediatric Fabry Disease: Insights into Early Diagnosis Monitoring. Biomedicines, 13(11), 2598. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13112598