The Role of Mitochondrial Genome Stability and Metabolic Plasticity in Thyroid Cancer

Abstract

1. Introduction

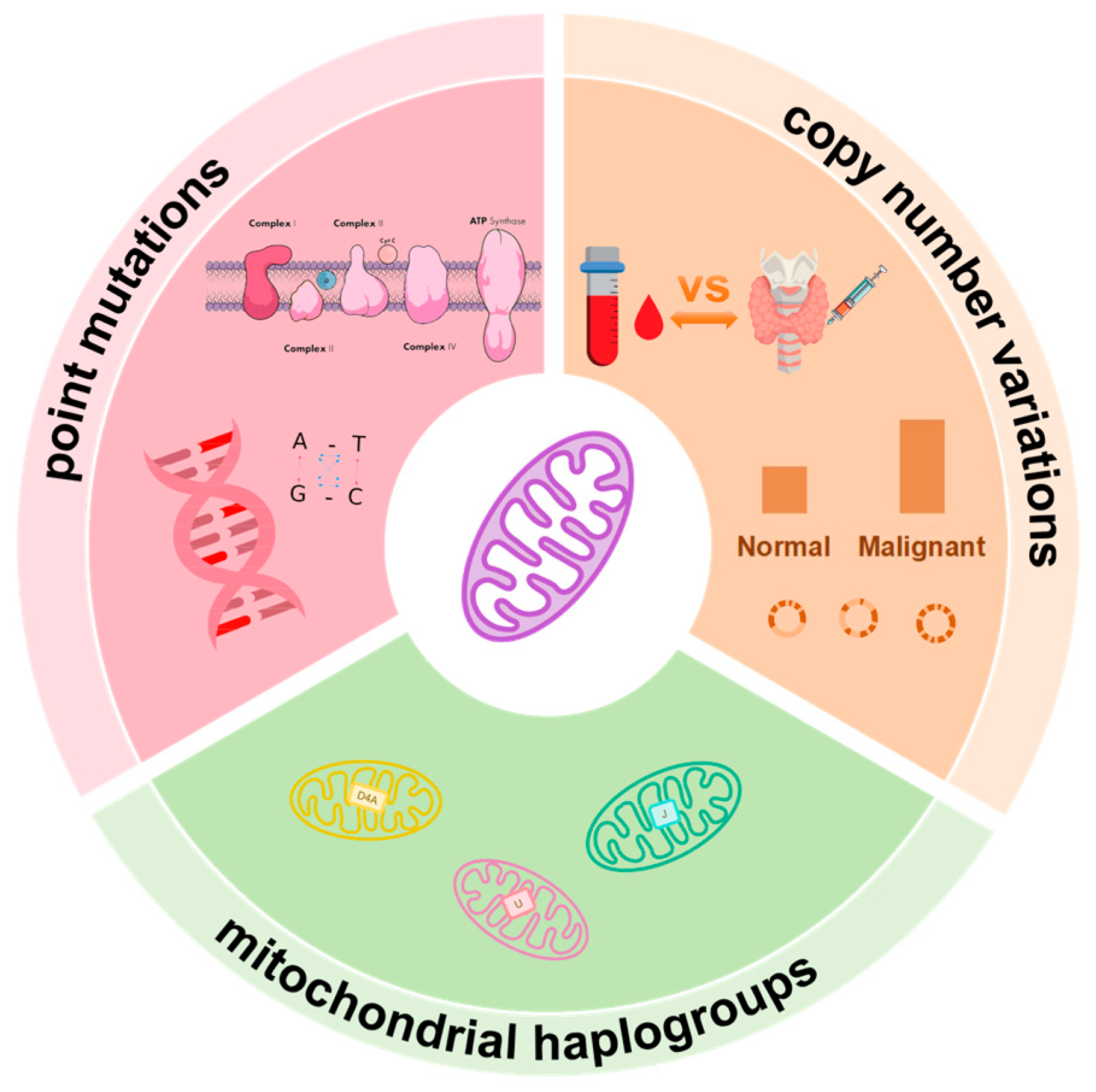

2. Mitochondrial Genome Instability and Malignant Progression of Thyroid Cancer

2.1. Molecular Characteristics of mtDNA

2.2. mtDNA Point Mutations in Thyroid Cancer

| Gene/Region | Variation | Type | Amino Acid (aa) Change | Cancer Type | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ND1/CI | 3308 T→C | Transition | M1T | PTC | [23] |

| 4216 T→C | Transition | Y303H | PTC, IC, FA | [23] | |

| 4225 A→G | Transition | M306V | PTC | [23] | |

| 4248 T→C | Transition | - | PTC | [23] | |

| 3842 G→A | Transition | W179X | FTC | [21,36] | |

| 3910 G→A | Transition | E202K | FTC | [23] | |

| 3594 C→T | Transition | - | PTC | [27] | |

| 3526 G→A | Transition | A74T | PTC | [27] | |

| 3571 ins C | Insertion | Frameshift | PTC-TCV | [31] | |

| 3955 G→C | Transversion | A217P | PTC-TCV | [31] | |

| 3380 G→A | Transition | R25Q | PTC-TCV | [31] | |

| ND2/CII | 4917 A→G | Transition | N149D | PTC, IC, FA | [23] |

| 4883 C→T | Transition | - | PTC | [23] | |

| 5298 A→G | Transition | I-V | PTC | [26] | |

| 5408 del A | Deletion | Frameshift | PTC | [23] | |

| 4940 C→T | Transition | - | PTC | [27] | |

| 4611–4612 del A | Deletion | Frameshift | PTC | [25] | |

| 4605 del A | Deletion | Frameshift | PTC-TCV | [31] | |

| 4611 del A | Deletion | Frameshift | PTC-TCV | [31] | |

| ND3/CI | 10,398 A→G | Transition | T113A | PTC, FTC, HT | [23] |

| 10,116 del AT | Deletion | 31X | PTC | [21] | |

| 10,320 G→A | Transition | V88I | PTC | [27] | |

| ND4/CI | 11,812 A→G | Transition | - | PTC, IC, FA | [23] |

| 11,126 G→A | Transition | E-K | PTC | [26] | |

| 11,736 T→C | Transition | L326P | PTC | [21] | |

| 11,840 C→T | Transition | - | PTC | [27] | |

| 11,179–11,180 ins T | Insertion | Frameshift | PTC | [25] | |

| 11,873 ins C | Insertion | Frameshift | PTC-TCV | [31] | |

| 11,038 del A | Deletion | Frameshift | PTC-TCV | [31] | |

| 11,364 C→T | Transition | A202V | PTC-TCV | [31] | |

| 10,946 ins C | Insertion | Frameshift | PTC-TCV | [31] | |

| 11,475 G→A | Transition | G239D | PTC-TCV | [31] | |

| ND4L/CI | 10,691 C→G | Transversion | - | FTC | [27] |

| ND5/CV | 13,617 T→C | Transition | - | PTC | [23] |

| 13,514 A→G | Transition | D-G | PTC | [26] | |

| 13,943 C→T | Transition | T536M | PTC | [27] | |

| 12,967 A→C | Transversion | T211P | FTC | [27] | |

| 13,805 C→T | Transition | A490V | PTC-TCV | [31] | |

| ND6 | 14,512 T→C | Transition | L121P | HT | [23] |

| 14,417 A→G | Transition | V-A | PTC | [26] | |

| 14,451–14,452 ins T | Insertion | Frameshift | PTC | [25] | |

| 14,660–14,661 del | Deletion | Frameshift | PTC-TCV | [31] | |

| 14,584 del T | Deletion | Frameshift | PTC-TCV | [31] | |

| CYTB/CIII | 15,326 A→G | Transition | T193A | PTC, FTC | [23] |

| 15,179 G→A | Transition | V144M | PTC | [23] | |

| 15,301 G→A | Transition | - | FTC | [23] | |

| 15,262 T→C | Transition | - | PTC | [23] | |

| 15,280 C→T | Transition | - | PTC | [27] | |

| 14,864 T→A | Transversion | C40S | PTC-TCV | [31] | |

| COI/CIV | 7389 T→C | Transition | Y495H | PTC | [23] |

| 7444 G→A | Transition | Ter496K | PTC | [23] | |

| 7424 A→G | Transition | - | FTC | [23] | |

| 7441 C→A | Transversion | S513Y | PTC | [21] | |

| 5979 G→A | Transition | A26T | PTC-TCV | [31] | |

| COII/CpIV | 7705 T→C | Transition | - | PTC | [23] |

| 8251 G→A | Transition | - | PTC | [23] | |

| 7785 T→ C | Transition | I67T | PTC | [27] | |

| 7658 G→A | Transition | D25N | PTC-TCV | [31] | |

| COIII/CpIV | 9380 G→A | Transition | - | HT | [23] |

| 9755 G→A | Transition | - | PTC | [23] | |

| 9932 G→A | Transition | - | PTC | [23] | |

| 9899 T→C | Transition | - | PTC | [23] | |

| 9948 G→A | Transition | V-I | PTC | [26] | |

| ATPase 6/CpV | 8725 A→G | Transition | T67A | PTC | [21] |

| ATPase 8/CpV | 8414 C→T | Transition | L16F | PTC | [23] |

| 12S rRNA | 663 A→G | Transition | PTC | [23] | |

| 709 G→A | Transition | PTC, IC, FA | [23] | ||

| 710 T→C | Transition | PTC | [23] | ||

| 16S rRNA | 3197 T→C | Transition | PTC | [23] | |

| tRNA Asp | 7521 G→A | Transition | PTC, IC | [23] | |

| tRNA Arg | 10,463 T→C | Transition | PTC, IC, FA | [23] | |

| tRNA Leu1 | 3244 G→A | Transition | PTC-TCV | [31] | |

| tRNA Leu2 | 12,308 A→G | Transition | PTC | [23] | |

| tRNA Ser | 7476 C→T | Transition | PTC | [26] |

2.3. Association of Mitochondrial Haplogroups with Clinical Phenotypes

2.4. mtDNA Copy Number Variations and Tumor Behavior

3. Role of Mitochondrial Metabolic Plasticity in Thyroid Cancer

3.1. Core Features and Manifestations of Metabolic Plasticity

3.2. Regulatory Mechanisms of Metabolic Plasticity

4. Interaction Mechanisms Between Mitochondrial Genome Variations and Thyroid Tumor Metabolic Plasticity

4.1. Interaction Between mtDNA Point Mutations and Metabolic Remodeling

4.2. Mitochondrial Haplogroups and Metabolic Tendencies

4.3. mtDNA Copy Number Variation and Metabolic Adaptation

5. Clinical Applications of mtDNA in Thyroid Cancer Diagnosis and Therapy

6. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Cancer Institute. Cancer Stat Facts: Thyroid Cancer. Available online: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/thyro.html (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Forma, A.; Klodnicka, K.; Pajak, W.; Flieger, J.; Teresinska, B.; Januszewski, J.; Baj, J. Thyroid Cancer: Epidemiology, Classification, Risk Factors, Diagnostic and Prognostic Markers, and Current Treatment Strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloch, Z.W.; Asa, S.L.; Barletta, J.A.; Ghossein, R.A.; Juhlin, C.C.; Jung, C.K.; LiVolsi, V.A.; Papotti, M.G.; Sobrinho-Simoes, M.; Tallini, G.; et al. Overview of the 2022 WHO Classification of Thyroid Neoplasms. Endocr. Pathol. 2022, 33, 27–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thanas, C.; Ziros, P.G.; Chartoumpekis, D.V.; Renaud, C.O.; Sykiotis, G.P. The Keap1/Nrf2 Signaling Pathway in the Thyroid—2020 Update. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massart, C.; Hoste, C.; Virion, A.; Ruf, J.; Dumont, J.E.; Van Sande, J. Cell biology of H2O2 generation in the thyroid: Investigation of the control of dual oxidases (DUOX) activity in intact ex vivo thyroid tissue and cell lines. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2011, 343, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Chang, J.Y.; Kang, Y.E.; Yi, S.; Lee, M.H.; Joung, K.H.; Kim, K.S.; Shong, M. Mitochondrial Energy Metabolism and Thyroid Cancers. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 30, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schon, E.A.; DiMauro, S.; Hirano, M. Human mitochondrial DNA: Roles of inherited and somatic mutations. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2012, 13, 878–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, X.; Wang, W.; Ruan, G.; Liang, M.; Zheng, J.; Chen, Y.; Wu, H.; Fahey, T.J.; Guan, M.; Teng, L. A Comprehensive Characterization of Mitochondrial Genome in Papillary Thyroid Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehuede, C.; Dupuy, F.; Rabinovitch, R.; Jones, R.G.; Siegel, P.M. Metabolic Plasticity as a Determinant of Tumor Growth and Metastasis. Cancer Res. 2016, 76, 5201–5208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Li, G.; Cui, G.; Duan, S.; Chang, S. Reprogramming of Thyroid Cancer Metabolism: From Mechanism to Therapeutic Strategy. Mol. Cancer 2025, 24, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burrows, N.; Resch, J.; Cowen, R.L.; von Wasielewski, R.; Hoang-Vu, C.; West, C.M.; Williams, K.J.; Brabant, G. Expression of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha in thyroid carcinomas. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2010, 17, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Borkhuu, O.; Bao, W.; Yang, Y.-T. Signaling Pathways in Thyroid Cancer and Their Therapeutic Implications. J. Clin. Med. Res. 2016, 8, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franco, A.T.; Malaguarnera, R.; Refetoff, S.; Liao, X.H.; Lundsmith, E.; Kimura, S.; Pritchard, C.; Marais, R.; Davies, T.F.; Weinstein, L.S.; et al. Thyrotrophin receptor signaling dependence of Braf-induced thyroid tumor initiation in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 1615–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, S.; Bankier, A.T.; Barrell, B.; Debruijn, M.; Coulson, A.; Drouin, J.; Eperon, I.; Nierlich, D.; Roe, B.; Sanger, F.; et al. Sequence and organization of the human mitochondrial genome. Nature 1981, 290, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexeyev, M.; Shokolenko, I.; Wilson, G.; LeDoux, S. The maintenance of mitochondrial DNA integrity—Critical analysis and update. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2013, 5, a012641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, D.C. Mitochondrial Genetics: A Paradigm for Aging and Degenerative Diseases? Science 1992, 256, 628–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ericson, N.G.; Kulawiec, M.; Vermulst, M.; Sheahan, K.; O’Sullivan, J.; Salk, J.J.; Bielas, J.H. Decreased mitochondrial DNA mutagenesis in human colorectal cancer. PLoS Genet. 2012, 8, e1002689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Ju, Y.S.; Kim, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Yoon, C.J.; Yang, Y.; Martincorena, I.; Creighton, C.J.; Weinstein, J.N.; et al. Comprehensive molecular characterization of mitochondrial genomes in human cancers. Nat. Genet. 2020, 52, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asa, S.L.; Mete, O. Oncocytic Change in Thyroid Pathology. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 678119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasparre, G.; Porcelli, A.M.; Bonora, E.; Pennisi, L.F.; Toller, M.; Iommarini, L.; Ghelli, A.; Moretti, M.; Betts, C.M.; Martinelli, G.N.; et al. Disruptive mitochondrial DNA mutations in complex I subunits are markers of oncocytic phenotype in thyroid tumors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 9001–9006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, L.; Wang, Q.; Song, S.; Li, L.; Zhou, H.; Li, M.; Jiang, Z.; Zhou, C.; Chen, G.; Lyu, J.; et al. Oncocytic tumors are marked by enhanced mitochondrial content and mtDNA mutations of complex I in Chinese patients. Mitochondrion 2019, 45, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, J.J.; Lunetta, K.L.; van Orsouw, N.J.; Moore, F.D., Jr.; Mutter, G.L.; Vijg, J.; Dahia, P.L.; Eng, C. Somatic mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) mutations in papillary thyroid carcinomas and differential mtDNA sequence variants in cases with thyroid tumours. Oncogene 2000, 19, 2060–2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maximo, V.; Lima, J.; Soares, P.; Botelho, T.; Gomes, L.; Sobrinho-Simoes, M. Mitochondrial D-Loop instability in thyroid tumours is not a marker of malignancy. Mitochondrion 2005, 5, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, F.A.; Neureiter, D.; Sperl, W.; Mayr, J.A.; Kofler, B. Alterations of Oxidative Phosphorylation Complexes in Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma. Cells 2018, 7, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu-Amero, K.K.; Alzahrani, A.S.; Zou, M.; Shi, Y. High frequency of somatic mitochondrial DNA mutations in human thyroid carcinomas and complex I respiratory defect in thyroid cancer cell lines. Oncogene 2005, 24, 1455–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maximo, V.; Soares, P.; Lima, J.; Cameselle-Teijeiro, J.; Sobrinho-Simoes, M. Mitochondrial DNA somatic mutations (point mutations and large deletions) and mitochondrial DNA variants in human thyroid pathology: A study with emphasis on Hurthle cell tumors. Am. J. Pathol. 2002, 160, 1857–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulaziz Binobead, M.; Al-Qahtani, W.H.; Alhumaidi Alotaibi, M.; Al-Shamarni, S.M.S.; Alghamdi, H.S.; Mostafa Domiaty, D.; Ahmed Safhi, F.; Abdullah Alduwish, M.; Abdulla Alwail, M.; Abdallah Al-Ghamdi, N.; et al. Impact of iodine supplementation and mtDNA mutations on papillary thyroid cancer in saudi women following a vegetarian diet. Cell. Mol. Biol. 2023, 69, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, B.C.; Ha, P.K.; Dhir, K.; Xing, M.; Westra, W.H.; Sidransky, D.; Califano, J.A. Mitochondrial DNA alterations in thyroid cancer. J. Surg. Oncol. 2003, 82, 170–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bircan, R.; Gözü, H.I.; Esra, U.; Sarikaya, Ş.; Gül, A.E.; Yaşar Şirin, D.; Özçelik, S.; Aral, C. The Mitochondrial DNA Control Region Might Have Useful Diagnostic and Prognostic Biomarkers for Thyroid Tumors. bioRxiv 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsybrovskyy, O.; De Luise, M.; de Biase, D.; Caporali, L.; Fiorini, C.; Gasparre, G.; Carelli, V.; Hackl, D.; Imamovic, L.; Haim, S.; et al. Papillary thyroid carcinoma tall cell variant shares accumulation of mitochondria, mitochondrial DNA mutations, and loss of oxidative phosphorylation complex I integrity with oncocytic tumors. J. Pathol. Clin. Res. 2022, 8, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Cheng, W.; Liu, C.; Li, J. Tall cell variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma: Current evidence on clinicopathologic features and molecular biology. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 40792–40799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissanka, N.; Moraes, C.T. Mitochondrial DNA heteroplasmy in disease and targeted nuclease-based therapeutic approaches. EMBO Rep. 2020, 21, e49612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Ji, J.; Chen, G.; Fang, H.; Yan, S.; Shen, L.; Wei, J.; Yang, K.; Lu, J.; Bai, Y. Analysis of mitochondrial DNA mutations in D-loop region in thyroid lesions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2010, 1800, 271–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragoszewski, P.; Kupryjanczyk, J.; Bartnik, E.; Rachinger, A.; Ostrowski, J. Limited clinical relevance of mitochondrial DNA mutation and gene expression analyses in ovarian cancer. BMC Cancer 2008, 8, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Bao, X.; Chen, H.; Jia, M.; Li, W.; Zhang, L.; Fan, R.; Fang, H.; Jin, L. Thyroid Cancer-Associated Mitochondrial DNA Mutation G3842A Promotes Tumorigenicity via ROS-Mediated ERK1/2 Activation. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 9982449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Fu, Q.; Xu, B.; Zhou, H.; Gao, J.; Shao, X.; Xiong, J.; Gu, Q.; Wen, S.; Li, F.; et al. Breast cancer-associated mitochondrial DNA haplogroup promotes neoplastic growth via ROS-mediated AKT activation. Int. J. Cancer 2018, 142, 1786–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, D.C. Mitochondrial DNA variation in human radiation and disease. Cell 2015, 163, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Shen, L.; Chen, T.; He, J.; Ding, Z.; Wei, J.; Qu, J.; Chen, G.; Lu, J.; Bai, Y. Cancer type-specific modulation of mitochondrial haplogroups in breast, colorectal and thyroid cancer. BMC Cancer 2010, 10, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocos, R.; Schipor, S.; Badiu, C.; Raicu, F. Mitochondrial DNA haplogroup K as a contributor to protection against thyroid cancer in a population from southeast Europe. Mitochondrion 2018, 39, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorelick, A.N.; Kim, M.; Chatila, W.K.; La, K.; Hakimi, A.A.; Berger, M.F.; Taylor, B.S.; Gammage, P.A.; Reznik, E. Respiratory complex and tissue lineage drive recurrent mutations in tumour mtDNA. Nat. Metab. 2021, 3, 558–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosgood, H.D., 3rd; Liu, C.S.; Rothman, N.; Weinstein, S.J.; Bonner, M.R.; Shen, M.; Lim, U.; Virtamo, J.; Cheng, W.L.; Albanes, D.; et al. Mitochondrial DNA copy number and lung cancer risk in a prospective cohort study. Carcinogenesis 2010, 31, 847–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thyagarajan, B.; Wang, R.; Nelson, H.; Barcelo, H.; Koh, W.P.; Yuan, J.M. Mitochondrial DNA copy number is associated with breast cancer risk. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e65968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, S.; Nomoto, S.; Fujii, T.; Kaneko, T.; Takeda, S.; Inoue, S.; Kanazumi, N.; Nakao, A. Correlation between copy number of mitochondrial DNA and clinico-pathologic parameters of hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2006, 32, 303–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, L.M.; Baccarelli, A.; Shu, X.O.; Gao, Y.T.; Ji, B.T.; Yang, G.; Li, H.L.; Hoxha, M.; Dioni, L.; Rothman, N.; et al. Mitochondrial DNA copy number and risk of gastric cancer: A report from the Shanghai Women’s Health Study. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2011, 20, 1944–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwehaidah, M.S.; Al-Awadhi, R.; Roomy, M.A.; Baqer, T.A. Mitochondrial DNA copy number and risk of papillary thyroid carcinoma. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2024, 24, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caglar Cil, O.; Metin, O.K.; Cayir, A. Evaluation of Mitochondrial Copy Number in Thyroid Disorders. Arch. Med. Res. 2022, 53, 711–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Chen, L.; Li, J.; Ma, J.; Luo, J.; Lv, Q.; Xiao, J.; Gao, P.; Chai, W.; Li, X.; et al. Mitochondrial DNA Copy Number and Risk of Diabetes Mellitus and Metabolic Syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2023, 109, e406–e417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stejskal, P.; Goodarzi, H.; Srovnal, J.; Hajduch, M.; van ’t Veer, L.J.; Magbanua, M.J.M. Circulating tumor nucleic acids: Biology, release mechanisms, and clinical relevance. Mol. Cancer 2023, 22, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; Huang, T.; Zhang, D.; Li, G.; Wei, L.; Liu, J. Elevated mitochondrial DNA copy number in euthyroid individuals with impaired peripheral sensitivity to thyroid hormones. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1635820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, R.G.; Fortunato, R.S.; Carvalho, D.P. Metabolic Reprogramming in Thyroid Carcinoma. Front. Oncol. 2018, 8, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vander Heiden, M.G.; Cantley, L.C.; Thompson, C.B. Understanding the Warburg effect: The metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science 2009, 324, 1029–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suh, H.Y.; Choi, H.; Paeng, J.C.; Cheon, G.J.; Chung, J.-K.; Kang, K.W. Comprehensive gene expression analysis for exploring the association between glucose metabolism and differentiation of thyroid cancer. BMC Cancer 2019, 19, 1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Shen, M.; Li, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhou, K.U.N.; Hu, W.; Xu, B.O.; Xia, Y.; Tang, W.E.I. GC-MS-based metabolomic analysis of human papillary thyroid carcinoma tissue. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2015, 36, 1607–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.Q.; Xi, C.; Ju, N.T.; Shen, C.T.; Qiu, Z.L.; Song, H.J.; Luo, Q.Y. Targeting glutamine metabolism exhibits anti-tumor effects in thyroid cancer. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 2024, 47, 1953–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abooshahab, R.; Hooshmand, K.; Razavi, F.; Dass, C.R.; Hedayati, M. A glance at the actual role of glutamine metabolism in thyroid tumorigenesis. EXCLI J. 2021, 20, 1170–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tufail, M.; Jiang, C.-H.; Li, N. Altered metabolism in cancer: Insights into energy pathways and therapeutic targets. Mol. Cancer 2024, 23, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Xing, Y.; Si, D.; Wang, S.; Lin, J.; Li, C.; Zhang, J.; Yin, D. Combined metabolomic and lipidomic analysis uncovers metabolic profile and biomarkers for papillary thyroid carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 17666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.H.; Yoon, S.J.; Kim, M.; Kim, H.H.; Song, Y.S.; Jung, J.W.; Han, D.; Cho, S.W.; Kwon, S.W.; Park, Y.J. Integrative Multi-omics Analysis Reveals Different Metabolic Phenotypes Based on Molecular Characteristics in Thyroid Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 30, 883–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denko, N.C. Hypoxia, HIF1 and glucose metabolism in the solid tumour. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2008, 8, 705–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, H.; Qiu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Xi, C.; Zhang, G.; Sun, Z.; Luo, Q.; Shen, C. HIF-1α/YAP Signaling Rewrites Glucose/Iodine Metabolism Program to Promote Papillary Thyroid Cancer Progression. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2023, 19, 225–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Chen, X.; Jiao, Q.; Qiu, Z.; Shen, C.; Zhang, G.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, H.; Luo, Q.-Y. HIF-1α-Mediated Telomerase Reverse Transcriptase Activation Inducing Autophagy Through Mammalian Target of Rapamycin Promotes Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma Progression During Hypoxia Stress. Thyroid 2021, 31, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podolski, A.; Castellucci, E.; Halmos, B. Precision medicine: BRAF mutations in thyroid cancer. Precis. Cancer Med. 2019, 2, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagarajah, J.; Ho, A.L.; Tuttle, R.M.; Weber, W.A.; Grewal, R.K. Correlation of BRAFV600E Mutation and Glucose Metabolism in Thyroid Cancer Patients: An (1)(8)F-FDG PET Study. J. Nucl. Med. 2015, 56, 662–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, S.-S.; Wu, Y.-J.; Wang, J.-Y.; Ni, Z.-X.; Dong, S.; Xie, X.-J.; Wang, Y.-T.; Wang, Y.; Huang, N.-S.; Ji, Q.-H.; et al. BRAFV600E/p-ERK/p-DRP1(Ser616) Promotes Tumor Progression and Reprogramming of Glucose Metabolism in Papillary Thyroid Cancer. Thyroid 2024, 34, 1246–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, C.; Gao, Y.; Wang, C.; Yu, X.; Zhang, W.; Guan, H.; Shan, Z.; Teng, W. Aberrant overexpression of pyruvate kinase M2 is associated with aggressive tumor features and the BRAF mutation in papillary thyroid cancer. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 98, E1524–E1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; Xi, Z.; Xiao, Y.; Zhao, X.; Li, J.; Feng, N.; Hu, L.; Zheng, R.; Zhang, N.; Wang, S.; et al. TSH-TSHR axis promotes tumor immune evasion. J. Immunother. Cancer 2022, 10, e004049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Ren, J.; Jing, Q.; Lu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yu, C.; Gao, P.; Zong, C.; Li, X.; et al. TSH/TSHR Signaling Suppresses Fatty Acid Synthase (FASN) Expression in Adipocytes. J. Cell. Physiol. 2015, 230, 2233–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, T.; Namba, H.; Takamura, N.; Yang, T.T.; Nagayama, Y.; Fukata, S.; Kuma, K.; Ishikawa, N.; Ito, K.; Yamashita, S. Thyrotropin Regulates c-Jun N-Terminal Kinase (JNK) Activity through Two Distinct Signal Pathways in Human Thyroid Cells. Endocrinology 1999, 140, 1724–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Guo, W.; Liu, Y.; Ji, X.; Guo, S.; Xie, F.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, K.; Zhang, H.; Peng, F.; Wu, D.; et al. Mutational signature of mtDNA confers mechanistic insight into oxidative metabolism remodeling in colorectal cancer. Theranostics 2023, 13, 324–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li-Harms, X.; Lu, J.; Fukuda, Y. Somatic mtDNA mutation burden shapes metabolic plasticity in leukemogenesis. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eads8489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonora, E.; Porcelli, A.M.; Gasparre, G.; Biondi, A.; Ghelli, A.; Carelli, V.; Baracca, A.; Tallini, G.; Martinuzzi, A.; Lenaz, G.; et al. Defective oxidative phosphorylation in thyroid oncocytic carcinoma is associated with pathogenic mitochondrial DNA mutations affecting complexes I and III. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 6087–6096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.S.; Sharma, L.K.; Li, H.; Xiang, R.; Holstein, D.; Wu, J.; Lechleiter, J.; Naylor, S.L.; Deng, J.J.; Lu, J.; et al. A heteroplasmic, not homoplasmic, mitochondrial DNA mutation promotes tumorigenesis via alteration in reactive oxygen species generation and apoptosis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2009, 18, 1578–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Guo, W.; Gu, X.; Guo, S.; Zhou, K.; Su, L.; Yuan, Q.; Liu, Y.; Guo, X.; Huang, Q.; et al. Mutational profiling of mtDNA control region reveals tumor-specific evolutionary selection involved in mitochondrial dysfunction. EBioMedicine 2022, 80, 104058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harino, T.; Tanaka, K.; Motooka, D.; Masuike, Y.; Takahashi, T.; Yamashita, K.; Saito, T.; Yamamoto, K.; Makino, T.; Kurokawa, Y.; et al. D-loop mutations in mitochondrial DNA are a risk factor for chemotherapy resistance in esophageal cancer. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 31653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishikawa, K.; Takenaga, K.; Akimoto, M.; Koshikawa, N.; Yamaguchi, A.; Imanishi, H.; Nakada, K.; Honma, Y.; Hayashi, J.-I. ROS-Generating Mitochondrial DNA Mutations Can Regulate Tumor Cell Metastasis. Science 2008, 320, 661–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetterman, J.L.; Ballinger, S.W. Mitochondrial genetics regulate nuclear gene expression through metabolites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 15763–15765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, W.P.; Chen, Y.L.; Luo, J.J.; Wang, C.; Xie, S.L.; Pei, D.S. Knock-In Strategy for Editing Human and Zebrafish Mitochondrial DNA Using Mito-CRISPR/Cas9 System. ACS Synth. Biol. 2019, 8, 621–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moraes, C.T. Tools for editing the mammalian mitochondrial genome. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2024, 33, R92–R99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shelton, S.D.; House, S.; Martins Nascentes Melo, L.; Ramesh, V.; Chen, Z.; Wei, T.; Wang, X.; Llamas, C.B.; Venigalla, S.S.K.; Menezes, C.J.; et al. Pathogenic mitochondrial DNA mutations inhibit melanoma metastasis. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadk8801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavadas, B.; Pereira, J.B.; Correia, M.; Fernandes, V.; Eloy, C.; Sobrinho-Simoes, M.; Soares, P.; Samuels, D.C.; Maximo, V.; Pereira, L. Genomic and transcriptomic characterization of the mitochondrial-rich oncocytic phenotype on a thyroid carcinoma background. Mitochondrion 2019, 46, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, C.W.; Qiu, R.Y.; Hu, N.Q.; Lü, J.X. Effect of Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroup M8a on Mitochondrial Energy Metabolism of Transmitochondrial Cybrids. Chin. J. Cell Biol. 2017, 39, 607–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghezzi, D.; Marelli, C.; Achilli, A.; Goldwurm, S.; Pezzoli, G.; Barone, P.; Pellecchia, M.T.; Stanzione, P.; Brusa, L.; Bentivoglio, A.R.; et al. Mitochondrial DNA haplogroup K is associated with a lower risk of Parkinson’s disease in Italians. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2005, 13, 748–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, X.; Qu, H.Q.; Liu, Y.; Glessner, J.T.; Hakonarson, H. Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroup K Is Protective Against Autism Spectrum Disorder Risk in Populations of European Ancestry. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2024, 63, 835–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caporali, L.; Moresco, M.; Pizza, F.; La Morgia, C.; Fiorini, C.; Strobbe, D.; Zenesini, C.; Hooshiar Kashani, B.; Torroni, A.; Pagotto, U.; et al. The role of mtDNA haplogroups on metabolic features in narcolepsy type 1. Mitochondrion 2022, 63, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunham-Snary, K.J.; Sandel, M.W.; Sammy, M.J.; Westbrook, D.G.; Xiao, R.; McMonigle, R.J.; Ratcliffe, W.F.; Penn, A.; Young, M.E.; Ballinger, S.W. Mitochondrial–nuclear genetic interaction modulates whole body metabolism, adiposity and gene expression in vivo. EBioMedicine 2018, 36, 316–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lechuga-Vieco, A.V.; Latorre-Pellicer, A.; Johnston, I.G.; Prota, G.; Gileadi, U.; Justo-Méndez, R.; Acín-Pérez, R.; Martínez-de-Mena, R.; Fernández-Toro, J.M.; Jimenez-Blasco, D. Cell identity and nucleo-mitochondrial genetic context modulate OXPHOS performance and determine somatic heteroplasmy dynamics. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaba5345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinker, A.E.; Vivian, C.J.; Beadnell, T.C.; Koestler, D.C.; Teoh, S.T.; Lunt, S.Y.; Welch, D.R. Mitochondrial haplotype of the host stromal microenvironment alters metastasis in a non-cell autonomous manner. Cancer Res. 2020, 80, 1118–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reznik, E.; Miller, M.L.; Senbabaoglu, Y.; Riaz, N.; Sarungbam, J.; Tickoo, S.K.; Al-Ahmadie, H.A.; Lee, W.; Seshan, V.E.; Hakimi, A.A.; et al. Mitochondrial DNA copy number variation across human cancers. Elife 2016, 5, e10769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-C.; Yin, P.-H.; Chi, C.-W.; Wei, Y.-H. Increase in mitochondrial mass in human fibroblasts under oxidative stress and during replicative cell senescence. J. Biomed. Sci. 2002, 9, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.C.; Wei, Y.H. Mitochondrial biogenesis and mitochondrial DNA maintenance of mammalian cells under oxidative stress. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2005, 37, 822–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.C.; Wei, Y.H. Mitochondrial DNA instability and metabolic shift in human cancers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2009, 10, 674–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doolittle, W.K.L.; Park, S.; Lee, S.G.; Jeong, S.; Lee, G.; Ryu, D.; Schoonjans, K.; Auwerx, J.; Lee, J.; Jo, Y.S. Non-genomic activation of the AKT-mTOR pathway by the mitochondrial stress response in thyroid cancer. Oncogene 2022, 41, 4893–4904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabane, P.; Correa, C.; Bode, I.; Aguilar, R.; Elorza, A.A. Biomarkers in Thyroid Cancer: Emerging Opportunities from Non-Coding RNAs and Mitochondrial Space. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M.A.; Yan-fang, L.; Jiang, L.; Di, X.; Wei, Q. Significance of mitochondrial DNA D-loop region gene mutation in human papillary thyroid carcinoma. J. Jiangsu Univ. (Med. Ed.) 2017, 27, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdas, E.; Stawski, R.; Kaczka, K.; Nowak, D.; Zubrzycka, M. Altered levels of circulating nuclear and mitochondrial DNA in patients with Papillary Thyroid Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 14438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codrich, M.; Biasotto, A.; D’Aurizio, F. Circulating Biomarkers of Thyroid Cancer: An Appraisal. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cote, G.J.; Evers, C.; Hu, M.I.; Grubbs, E.G.; Williams, M.D.; Hai, T.; Duose, D.Y.; Houston, M.R.; Bui, J.H.; Mehrotra, M.; et al. Prognostic Significance of Circulating RET M918T Mutated Tumor DNA in Patients With Advanced Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2017, 102, 3591–3599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Peng, F.; Wang, S.; Jiao, H.; Dang, M.; Zhou, K.; Guo, W.; Guo, S.; Zhang, H.; Song, W.; et al. Aberrant fragmentomic features of circulating cell-free mitochondrial DNA as novel biomarkers for multi-cancer detection. EMBO Mol. Med. 2024, 16, 3169–3183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, P.; Liu, L.; Bancaro, N.; Troiani, M.; Cali, B.; Li, Y.; Chen, J.; Singh, P.K.; Arzola, R.A.; Attanasio, G.; et al. Mitochondrial DNA released by senescent tumor cells enhances PMN-MDSC-driven immunosuppression through the cGAS-STING pathway. Immunity 2025, 58, 811–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, Y.D.; Chen, W.T.; Lin, W.R.; Lai, M.W.; Yeh, C.T. Mitochondrial echoes in the bloodstream: Decoding ccf-mtDNA for the early detection and prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Biosci. 2025, 15, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Pol, Y.; Moldovan, N.; Ramaker, J.; Bootsma, S.; Lenos, K.J.; Vermeulen, L.; Sandhu, S.; Bahce, I.; Pegtel, D.M.; Wong, S.Q.; et al. The landscape of cell-free mitochondrial DNA in liquid biopsy for cancer detection. Genome Biol. 2023, 24, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.L. Correlation Analysis Between Mitochondrial DNAComplexlV Mutation and Thyroid Tumors; Wenzhou Medical University: Wenzhou, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Francesco, M.E.D.; Marszalek, J.R.; McAfoos, T.; Carroll, C.L.; Kang, Z.; Liu, G.; Theroff, J.P.; Bardenhager, J.P.; Bandi, M.L.; Molina, J.R.; et al. Abstract 1655: Discovery and development of IACS-010759, a novel inhibitor of Complex I currently in phase I studies to exploit oxidative phosphorylation dependency in acute myeloid leukemia and solid tumors. Cancer Res. 2018, 78, 1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuji, A.; Akao, T.; Masuya, T.; Murai, M.; Miyoshi, H. IACS-010759, a potent inhibitor of glycolysis-deficient hypoxic tumor cells, inhibits mitochondrial respiratory complex I through a unique mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 7481–7491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baran, N.; Molina, J.; Cavazos, A.; Harutyunyan, K.; Feng, N.; Gay, J.; Piya, S.; Shanmuga Velandy, S.; Jabbour, E.J.; Andreeff, M.; et al. Mitochondrial Complex I Inhibition with Iacs-010759 in T-ALL Preclinical Models. Blood 2016, 128, 4028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, M.; Zhang, W.; Bennett, M.; Emberley, E.; Gross, M.; Janes, J.; MacKinnon, A.; Pan, A.; Steggerda, S.; Works, M.; et al. Abstract 4711: CB-839, a selective glutaminase inhibitor, synergizes with signal transduction pathway inhibitors to enhance anti-tumor activity. Cancer Res. 2015, 75, 4711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouda, M.A.; Voss, M.H.; Tawbi, H.; Gordon, M.; Tykodi, S.S.; Lam, E.T.; Vaishampayan, U.; Tannir, N.M.; Chaves, J.; Nikolinakos, P.; et al. A phase I/II study of the safety and efficacy of telaglenastat (CB-839) in combination with nivolumab in patients with metastatic melanoma, renal cell carcinoma, and non-small-cell lung cancer. ESMO Open 2025, 10, 104536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timofeeva, N.; Ayres, M.L.; Baran, N.; Santiago-O’Farrill, J.M.; Bildik, G.; Lu, Z.; Konopleva, M.; Gandhi, V. Preclinical investigations of the efficacy of the glutaminase inhibitor CB-839 alone and in combinations in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1161254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, P.; Zhou, C.; Lu, L.; Liu, B.; Ding, Y. Elesclomol: A copper ionophore targeting mitochondrial metabolism for cancer therapy. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 41, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Wu, X.; Huang, S.; Zhao, Z.; He, W.; Song, M. Novel insights into anticancer mechanisms of elesclomol: More than a prooxidant drug. Redox Biol. 2023, 67, 102891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y.; Tang, L.; Wang, X.; Ji, Y.; Tu, Y. Nrf2 in human cancers: Biological significance and therapeutic potential. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2024, 14, 3935–3961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panieri, E.; Saso, L. Inhibition of the NRF2/KEAP1 Axis: A Promising Therapeutic Strategy to Alter Redox Balance of Cancer Cells. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2021, 34, 1428–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Wang, X.; Zhou, M.; Fei, H. A mitochondria-targeting gold-peptide nanoassembly for enhanced cancer-cell killing. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2013, 2, 1638–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kodiha, M.; Wang, Y.M.; Hutter, E.; Maysinger, D.; Stochaj, U. Off to the organelles—Killing cancer cells with targeted gold nanoparticles. Theranostics 2015, 5, 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, Y.; Peng, A.; Yang, J.; Cheng, Z.; Yue, Y.; Liu, F.; Li, F.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Q. Precisely Activating cGAS-STING Pathway with a Novel Peptide-Based Nanoagonist to Potentiate Immune Checkpoint Blockade Cancer Immunotherapy. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, e2309583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacman, S.R.; Kauppila, J.H.K.; Pereira, C.V.; Nissanka, N.; Miranda, M.; Pinto, M.; Williams, S.L.; Larsson, N.G.; Stewart, J.B.; Moraes, C.T. MitoTALEN reduces mutant mtDNA load and restores tRNA(Ala) levels in a mouse model of heteroplasmic mtDNA mutation. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 1696–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoop, W.K.; Lape, J.; Trum, M.; Powell, A.; Sevigny, E.; Mischler, A.; Bacman, S.R.; Fontanesi, F.; Smith, J.; Jantz, D.; et al. Efficient elimination of MELAS-associated m.3243G mutant mitochondrial DNA by an engineered mitoARCUS nuclease. Nat. Metab. 2023, 5, 2169–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Lee, H.; Baek, G.; Kim, J.S. Precision mitochondrial DNA editing with high-fidelity DddA-derived base editors. Nat. Biotechnol. 2023, 41, 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mok, B.Y.; de Moraes, M.H.; Zeng, J.; Bosch, D.E.; Kotrys, A.V.; Raguram, A.; Hsu, F.; Radey, M.C.; Peterson, S.B.; Mootha, V.K.; et al. A bacterial cytidine deaminase toxin enables CRISPR-free mitochondrial base editing. Nature 2020, 583, 631–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.; Jin, M.; Huang, S.; Yao, F.; Ren, N.; Xu, K.; Li, S.; Gao, P.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; et al. Enhanced C-To-T and A-To-G Base Editing in Mitochondrial DNA with Engineered DdCBE and TALED. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, e2304113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, J.; Du, K. Mitochondrial base editing: From principle, optimization to application. Cell Biosci. 2025, 15, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Alteration/Target | Mechanism/Observation | Potential Clinical Application | Limitations | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic | mtDNA D-loop mutations | Regulatory hotspot; frequent in PTC but also in benign lesions | Early detection, risk stratification | Limited specificity; occurs in benign lesions; heteroplasmy complicates interpretation | [24,95] |

| mtDNA copy number alterations | Increased in PTC and adenomas vs. nodular goiter | Potential biomarker to distinguish benign vs. malignant nodules | Conflicting results between tissue and blood; methodological variability; lack of standard thresholds | [46] | |

| Circulating cf-mtDNA | Reduced in PTC plasma | Minimally invasive detection; prognostic assessment | Low abundance; detection sensitivity limited; blood origin may include non-tumor cells; inter-study variability | [96,98,99,100,101,102] | |

| Therapeutic—Metabolic Targeting | Complex I/ND subunits, COX1/2 mutations | OXPHOS dysfunction, ROS accumulation | Complex I inhibitors (IACS-010759), glutaminase inhibitors (CB-839) | Mostly preclinical; unclear efficacy and safety in patients; heterogeneity in tumor metabolic profiles | [103,104,105,106,107,108,109] |

| Therapeutic—Redox Modulation | ROS imbalance/antioxidant pathways | Excessive ROS, metabolic remodeling | Elesclomol, NRF2 inhibitors | Early stage; systemic toxicity possible; context-dependent efficacy | [110,111,112,113] |

| Therapeutic—Nanoparticles | KLA-Au systems | Mitochondrial accumulation, oxidative damage, mtDNA release | Induction of innate immunity, potential anti-tumor effect | Preclinical; pharmacokinetics, targeting efficiency, and safety not fully established | [114,115,116] |

| Therapeutic—Genetic Editing | mtDNA mutations | Targeted mutation reduction or base editing | mitoTALENs, mitoARCUS, DdCBEs | Early stage; delivery efficiency, off-target effects, and nuclear-mitochondrial interaction concerns | [117,118,119,120,121,122] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ren, L.; Liu, W.; Zheng, J.; Wu, Q.; Ai, Z. The Role of Mitochondrial Genome Stability and Metabolic Plasticity in Thyroid Cancer. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2599. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13112599

Ren L, Liu W, Zheng J, Wu Q, Ai Z. The Role of Mitochondrial Genome Stability and Metabolic Plasticity in Thyroid Cancer. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(11):2599. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13112599

Chicago/Turabian StyleRen, Lingyu, Wei Liu, Jiaojiao Zheng, Qiao Wu, and Zhilong Ai. 2025. "The Role of Mitochondrial Genome Stability and Metabolic Plasticity in Thyroid Cancer" Biomedicines 13, no. 11: 2599. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13112599

APA StyleRen, L., Liu, W., Zheng, J., Wu, Q., & Ai, Z. (2025). The Role of Mitochondrial Genome Stability and Metabolic Plasticity in Thyroid Cancer. Biomedicines, 13(11), 2599. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13112599