Antiviral Activity of Origanum vulgare ssp. hirtum Essential Oil-Loaded Polymeric Micelles

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

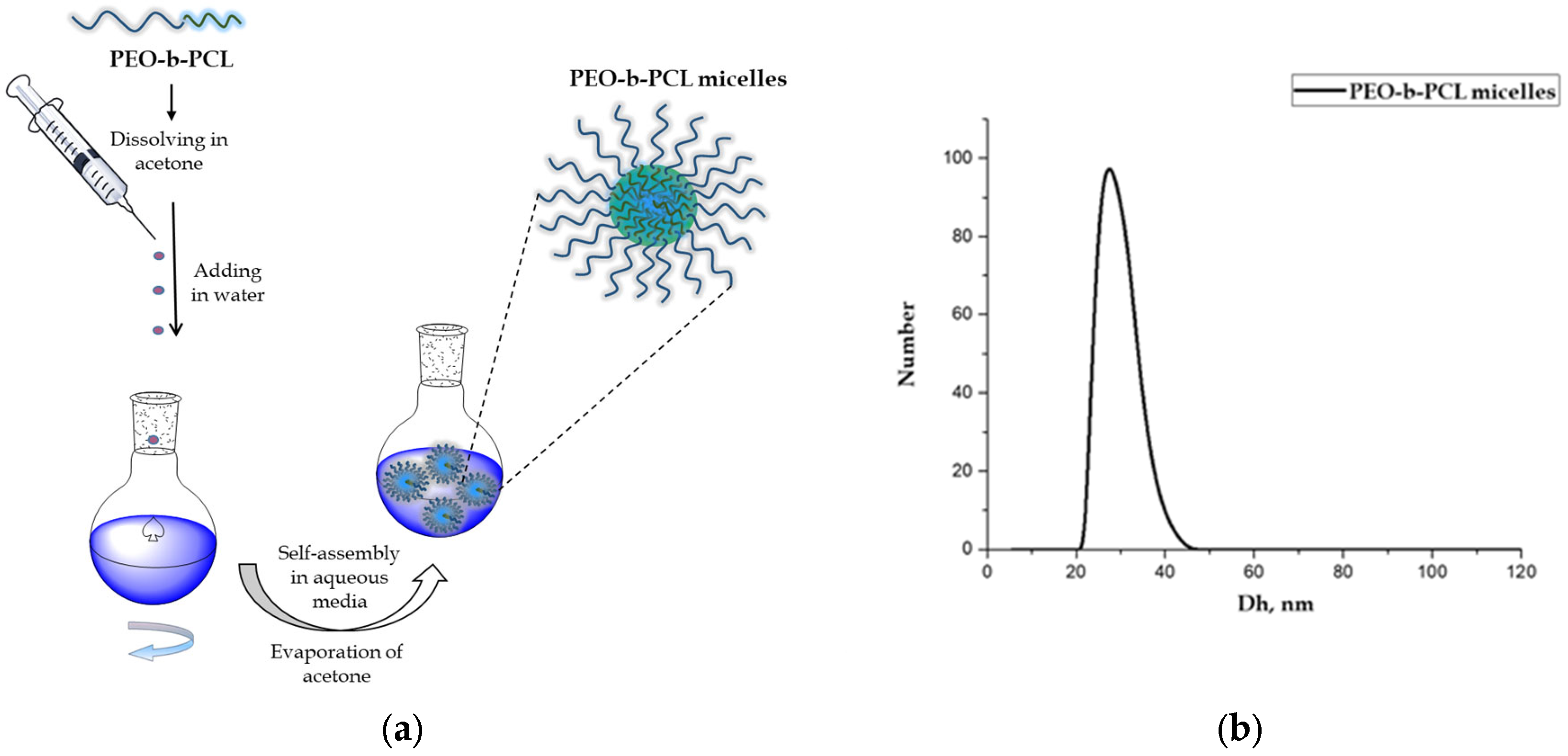

2.2. Preparation of PEO-b-PCL Block Copolymer Micelles

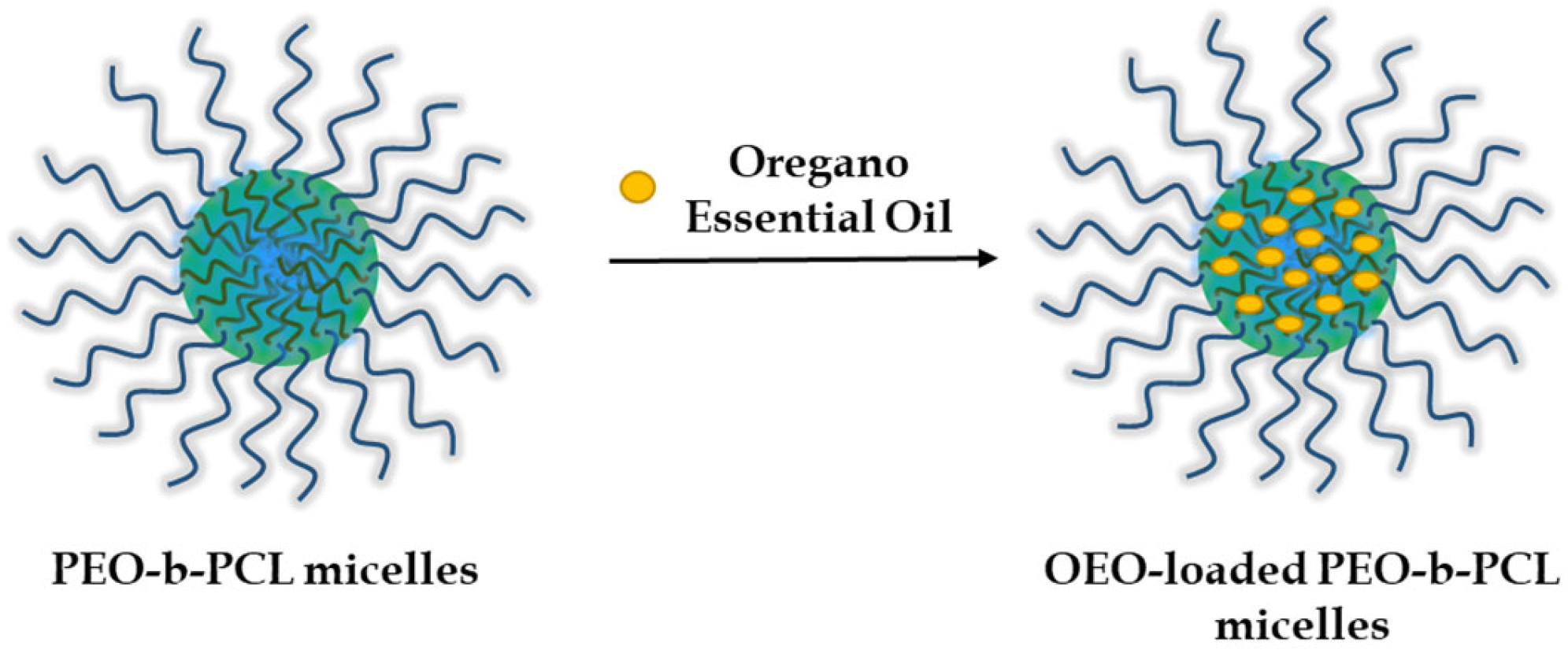

2.3. Preparation of OEO-Loaded PEO-b-PCL Block Copolymer Micelles

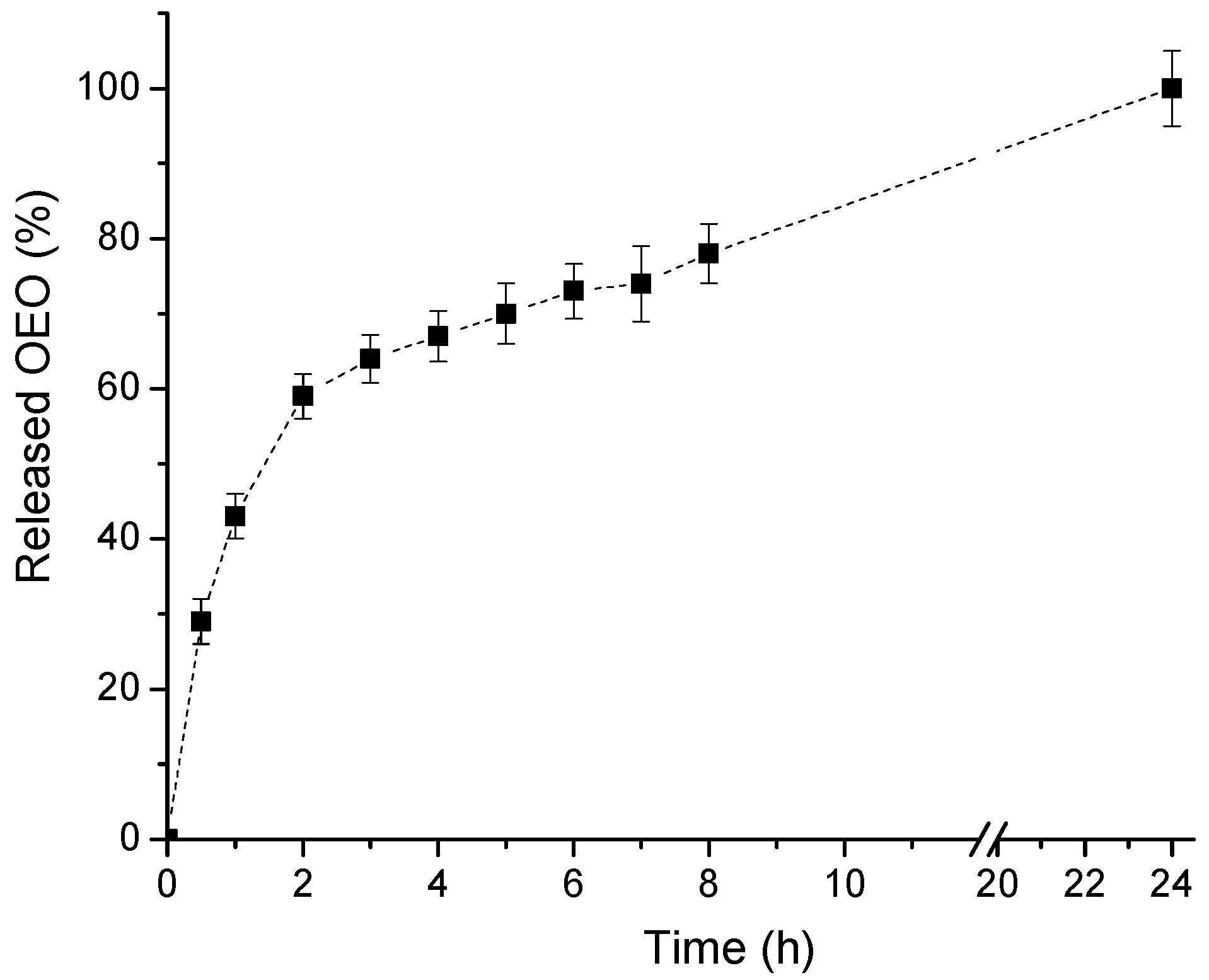

2.4. In Vitro Release of OEO

2.5. Analysis

2.6. Host Cell Lines

2.7. Viruses

2.8. Reference Compound

2.9. In Vitro Safety Testing

2.10. Cytotoxicity Assay

2.11. Determination of Infectious Viral Titers

2.12. Antiviral Activity Assay

2.13. Effect on Viral Adsorption

2.14. Virucidal Assay

2.15. Pre-Treatment of Healthy Cells

2.16. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Preparation and Characterization of PEO-b-PCL Block Copolymer Micelles

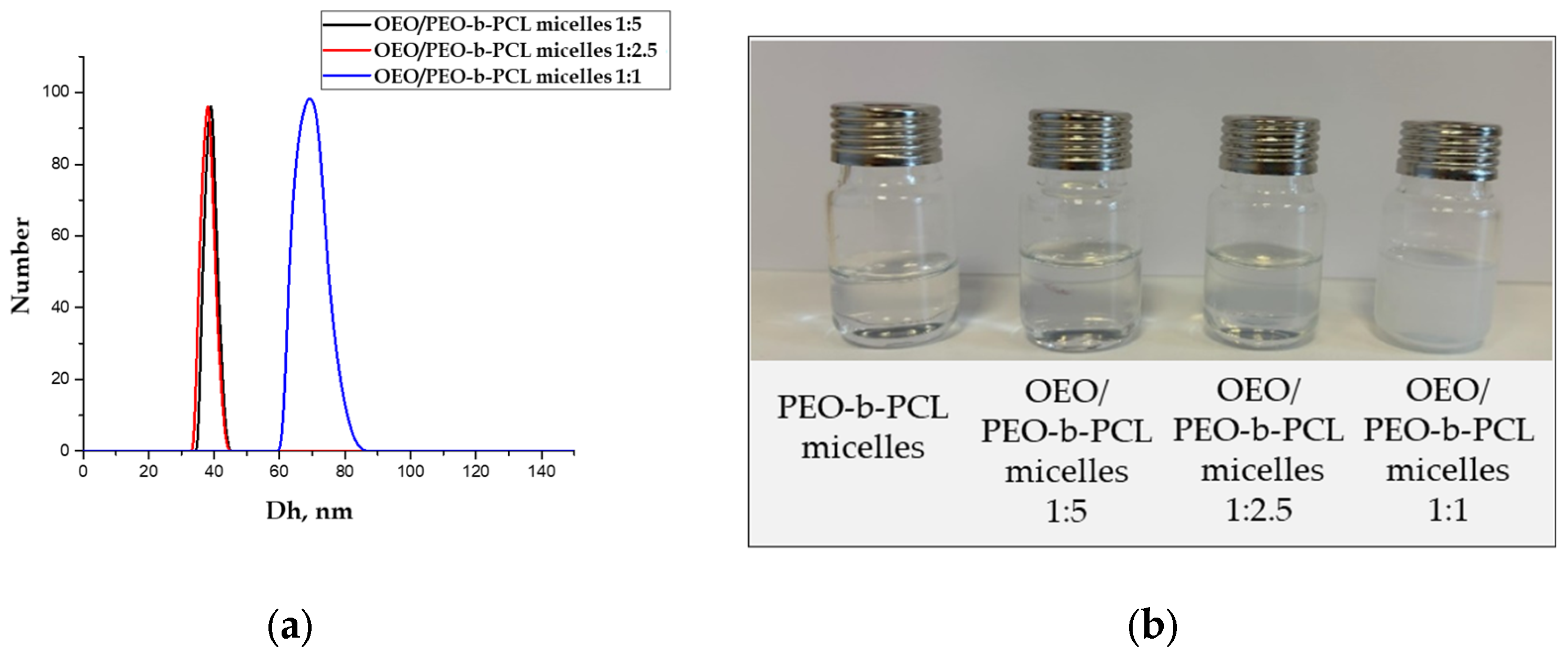

3.2. Preparation and Characterization of OEO-Loaded PEO-b-PCL Block Copolymer Micelles

3.3. Biological Assessment

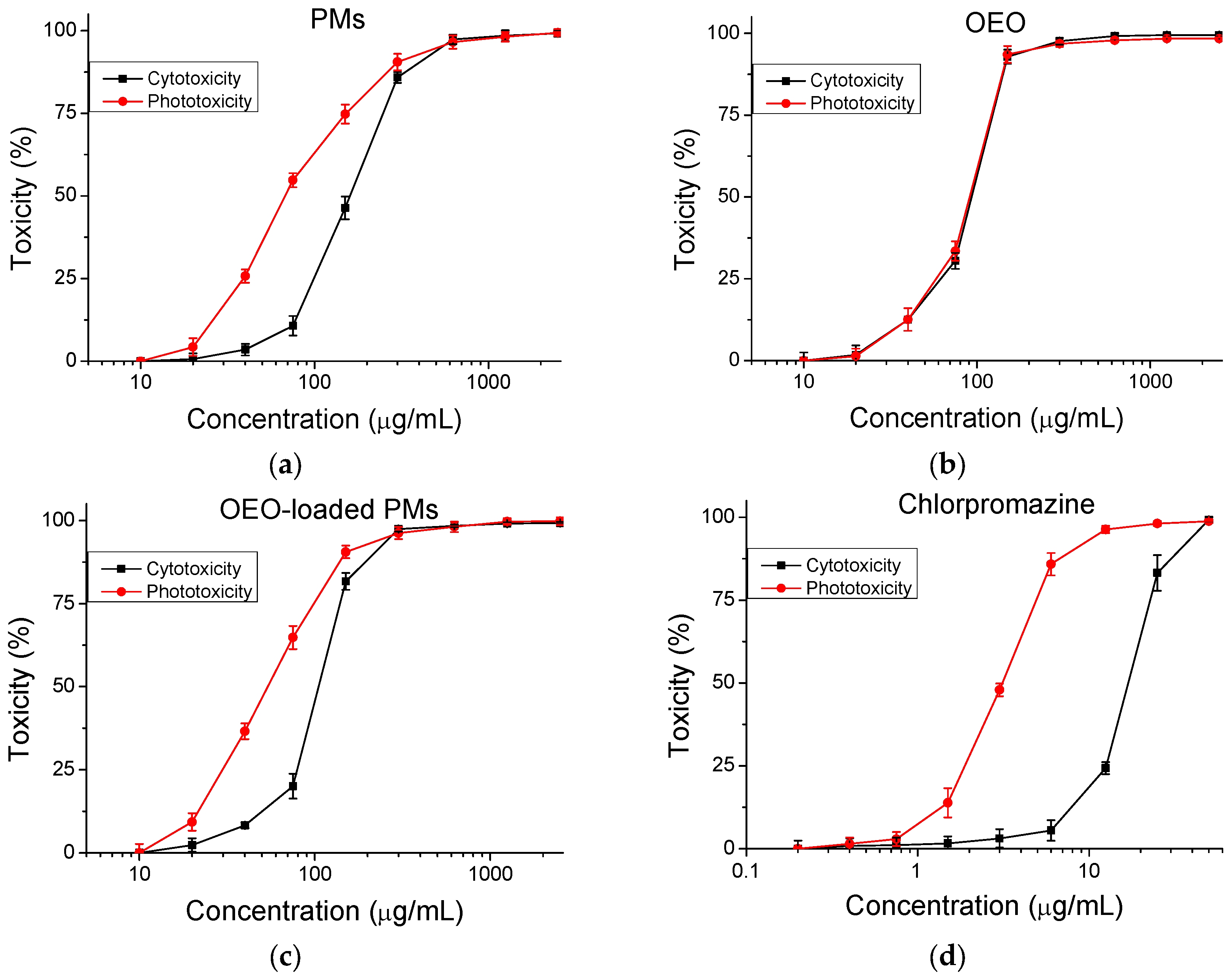

3.3.1. Cytotoxicity

3.3.2. Antiviral Activity

4. Discussion

- Extracellular virions. Reducing the ability of virions to infect susceptible cells is based on the ability of some chemical compounds to non-specifically inactivate virions outside the cell by denaturing viral proteins and/or causing structural changes in the lipids of the supercapsid.

- Attachment (adsorption), in which the binding of viral structures and cellular receptors responsible for recognizing the susceptible cell by the viral particle is disrupted.

- Virus fusion—preventing the fusion of the viral supercapsid with the cell membrane. This stops the virus from entering the cell.

- Intracellular replicative cycle (includes transcription of viral genes, translation of viral proteins, and replication of the viral genome). Viruses induce a large number of virus-specific enzymes in the infected cell. They duplicate the action of analogous cellular enzymes but differ from them in a number of physicochemical characteristics: molecular mass, requirement for certain cations, sensitivity to inhibitors, and substrate specificity.

- Assembly of new virus particles—if this step is affected, defective virus particles can be formed that cannot infect other cells.

- Release from the infected cell—if this step is blocked, new cells will not be able to be infected [60].

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lozano, R.; Naghavi, M.; Foreman, K.; Lim, S.; Shibuya, K.; Aboyans, V.; Abraham, J.; Adair, T.; Aggarwal, R.; Ahn, S.Y.; et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012, 380, 2095–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Civitelli, L.; Panella, S.; Marcocci, M.E.; De Petris, A.; Garzoli, S.; Pepi, F.; Vavala, E.; Ragno, R.; Nencioni, L.; Palamara, A.; et al. In vitro inhibition of herpes simplex virus type 1 replication by Mentha suaveolens essential oil and its main component piperitenone oxide. Phytomedicine 2014, 21, 857–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orhan, I.E.; Özçelik, B.; Kartal, M.; Kan, Y. Antimicrobial and antiviral effects of essential oils from selected Umbelliferae and Labiatae plants and individual essential oil components. Turk. J. Biol. 2012, 36, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, K.; Obossou, E.K.; Suwa, S.; Miura, S.; Oh, S.; Jinbo, N.; Ishibashi, Y.; Shikamoto, Y.; Hosono, T.; Toda, T. Human Immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) reverse transcriptase inhibitory effect of Cymbopogon nardus essential oil. Int. J. Adv. Res. 2016, 2, 7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, A.D.; Kaur, I. Eucalyptol (1,8-cineole) from eucalyptus essential oil: A potential inhibitor of COVID-19 coronavirus infection by molecular docking studies. EuropePMC 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelli, I.; Hassani, F.; Brikci, S.B.; Ghalem, S. In silico study of the inhibition of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 receptor of COVID-19 by Ammoides verticillata components harvested from western Algeria. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020, 39, 3263–3276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vimalanathan, S.; Hudson, J. The activity of cedar leaf oil vapor against respiratory viruses: Practical applications. J. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 3, 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Pilau, M.R.; Alves, S.H.; Weiblen, R.; Arenhart, S.; Cueto, A.P.; Lovato, L.T. Antiviral activity of Lippia graveolens (Mexican oregano) essential oil and its main compound carvacrol against human and animal viruses. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2011, 42, 1616–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, L.A.; Stashenko, E.E.; Ocazionez, R.E. Comparative study on in vitro activities of citral, limonene and essential oils from Lippia citriodora and L. alba on yellow fever virus. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2013, 8, 249–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, J.G.; Picard, M.; Bénard, S.; Desvignes, C.; Desprès, P.; Diotel, N.; El Kalamouni, C. Ayapana triplinervis essential oil and its main component thymohydroquinone dimethyl ether inhibit Zika virus at doses devoid of toxicity in zebrafish. Molecules 2019, 24, 3447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camero, M.; Lanave, G.; Catella, C.; Capozza, P.; Gentile, A.; Fracchiolla, G.; Britti, M.; Martella, V.; Buonavoglia, C.; Tempesta, M. Virucidal activity of ginger essential oil against caprine alphaherpesvirus-1. Veter. Microbiol. 2019, 230, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Yao, L. Antiviral effects of plant-derived essential oils and their components: An updated review. Molecules 2020, 25, 2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Mokni, R.; Youssef, F.S.; Jmii, H.; Khmiri, A.; Bouazzi, S.; Jlassi, I.; Jaidane, H.; Dhaouadi, H.; Ashour, M.L.; Hammami, S. The essential oil of Tunisian Dysphania ambrosioides and its antimicrobial and antiviral properties. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants 2019, 22, 282–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elaissi, A.; Rouis, Z.; Ben Salem, N.A.; Mabrouk, S.; Ben Salem, Y.; Salah, K.B.H.; Aouni, M.; Farhat, F.; Chemli, R.; Harzallah-Skhiri, F.; et al. Chemical composition of 8 eucalyptus species’ essential oils and evaluation of their antibacterial, antifungal and antiviral activities. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2012, 12, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilling, D.; Kitajima, M.; Torrey, J.; Bright, K.R. Antiviral efficacy and mechanisms of action of oregano essential oil and its primary component carvacrol against murine norovirus. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2014, 116, 1149–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, C.; Aznar, R.; Sanchez, G. The effect of carvacrol on enteric viruses. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2015, 192, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi-Rad, J.; Salehi, B.; Schnitzler, P.; Ayatollahi, S.A.; Kobarfard, F.; Fathi, M.; Eisazadeh, M.; Sharifi-Rad, M. Susceptibility of herpes simplex virus type 1 to monoterpenes thymol, carvacrol, p-cymene and essential oils of Sinapis arvensis L., Lallemantia royleana Benth and Pulicaria vulgaris Gaertn. Cell Mol. Biol. 2017, 63, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakkas, H.; Papadopoulou, C. Antimicrobial activity of basil, oregano, and thyme essential oils. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 27, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bekut, M.; Brkić, S.; Kladar, N.; Dragović, G.; Gavarić, N.; Božin, B. Potential of selected Lamiaceae plants in anti(retro)viral therapy. Pharmacol. Res. 2018, 133, 301–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mediouni, S.; Jablonski, J.A.; Tsuda, S.; Barsamian, A.; Kessing, C.; Richard, A.; Biswas, A.; Toledo, F.; Andrade, V.M.; Even, Y.; et al. Oregano oil and its principal component, carvacrol, inhibit HIV-1 fusion into target cells. J. Virol. 2020, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Deng, Y.; Song, T.; Pang, L.; Zhu, S.; Ren, Z.; Guo, H.; Xu, Z.; Zhu, L.; Geng, Y.; et al. Evaluation of the activity and mechanisms of oregano essential oil against PRV in vivo and in vitro. Microb. Pathog. 2024, 194, 106791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preuss, H.G.; Aruoma, O.I. Suggestions for combatting COVID-19 by natural means in absence of standard medical regimens. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2020, 40, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, S.M.; Crowe, S.M.; Mak, J. Virion-associated cholesterol is critical for maintenance of HIV-1 structure and infectivity. AIDS 2002, 16, 2253–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundaram, R.V.K.; Li, H.; Bailey, L.; Rashad, A.A.; Aneja, R.; Weiss, K.; Huynh, J.; Bastian, A.R.; Papazoglou, E.; Abrams, C.; et al. Impact of HIV-1 membrane cholesterol on cell-independent lytic inactivation and cellular infectivity. Biochemistry 2016, 55, 447–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aizaki, H.; Morikawa, K.; Fukasawa, M.; Hara, H.; Inoue, Y.; Tani, H.; Saito, K.; Nishijima, M.; Hanada, K.; Matsuura, Y.; et al. Critical role of virion-associated cholesterol and sphingolipid in hepatitis C virus infection. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 5715–5724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Whittaker, G.R. Role for influenza virus envelope cholesterol in virus entry and infection. J. Virol. 2003, 77, 12543–12551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajimaya, S.; Frankl, T.; Hayashi, T.; Takimoto, T. Cholesterol is required for stability and infectivity of influenza A and respiratory syncytial viruses. Virology 2017, 510, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husain, I.; Ahmad, R.; Siddiqui, S.; Chandra, A.; Misra, A.; Srivastava, A.; Ahamad, T.; Khan, M.F.; Siddiqi, Z.; Trivedi, A.; et al. Structural interactions of phytoconstituent(s) from cinnamon, bay leaf, oregano, and parsley with SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein: A comparative assessment for development of antiviral nutraceuticals. J. Food Biochem. 2022, 46, e14262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maus, A.; Strait, L.; Zhu, D. Nanoparticles as delivery vehicles for antiviral therapeutic drugs. Eng. Regen. 2021, 2, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stan, D.; Enciu, A.M.; Mateescu, A.L.; Ion, A.C.; Brezeanu, A.C.; Stan, D.; Tanase, C. Natural compounds with antimicrobial and antiviral effect and nanocarriers used for their transportation. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 723233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lembo, D.; Cavalli, R. Nanoparticulate delivery systems for antiviral drugs. Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 2010, 21, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurunathan, S.; Qasim, M.; Choi, Y.; Do, J.T.; Park, C.; Hong, K.; Kim, J.H.; Song, H. Antiviral potential of nanoparticles—Can nanoparticles fight against coronaviruses? Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoncheva, K.; Benbassat, N.; Zaharieva, M.M.; Dimitrova, L.; Kroumov, A.; Spassova, I.; Kovacheva, D.; Najdenski, H.M. Improvement of the antimicrobial activity of oregano oil by encapsulation in chitosan–alginate nanoparticles. Molecules 2021, 26, 7017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Liu, P.; Ye, K.; He, Y.; Chen, S.; Yuan, A.; Chen, F.; Yang, W. Preparation, characterization, in vitro release, and antibacterial activity of oregano essential oil chitosan nanoparticles. Foods 2022, 11, 3756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vehapi, M.; Yilmaz, A.; Özçimen, D. Fabrication of oregano-olive oil loaded PVA/chitosan nanoparticles via electrospraying method. J. Nat. Fibers 2021, 18, 1359–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, J.R.; Bonfim, K.S.; Lorevice, M.V.; Correa, D.S.; Mattoso, L.H.C.; de Moura, M.R. Antibacterial properties of oregano essential oil encapsulated in poly(ε-caprolactone) nanoparticles. Adv. Sci. Eng. Med. 2020, 12, 864–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radeva, L.; Zaharieva, M.M.; Naydenska, S.; Foka, P.; Karamichali, E.; Koufogeorgou, E.I.; Georgopoulou, U.; Philipov, S.; Kroumov, A.; Najdenski, H.; et al. Loading of oregano oil in natural nanogel and preliminary studies on its antiviral activity on betacoronavirus 1. Molecules 2025, 30, 1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiriac, A.P.; Rusu, A.G.; Nita, L.E.; Chiriac, V.M.; Neamtu, I.; Sandu, A. Polymeric carriers designed for encapsulation of essential oils with biological activity. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, R.R.; Souza, A.G.; Rosa, D.S. Essential oil-loaded nanocapsules and their application on PBAT biodegradable films. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 337, 116488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldawsari, M.F.; Foudah, A.I.; Rawat, P.; Alam, A.; Salkini, M.A. Nanogel-based delivery system for lemongrass essential oil: A promising approach to overcome antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. Gels 2023, 9, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, A.; Jarak, I.; Santos, A.; Veiga, F.; Figueiras, A. Polymeric micelles: A promising pathway for dermal drug delivery. Materials 2021, 14, 7278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuperkar, K.; Patel, D.; Atanase, L.I.; Bahadur, P. Amphiphilic block copolymers: Their structures, and self-assembly to polymeric micelles and polymersomes as drug delivery vehicles. Polymers 2022, 14, 4702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyemi, S.B.; Akere, A.M.; Orege, J.I.; Ejeromeghene, O.; Orege, O.B.; Akolade, J.O. Polymeric nanoparticles for enhanced delivery and improved bioactivity of essential oils. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chountoulesi, M.; Selianitis, D.; Pispas, S.; Pippa, N. Recent advances on PEO-PCL block and graft copolymers as nanocarriers for drug delivery applications. Materials 2023, 16, 2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, R.; Farah, A.; Binkhathlan, Z. Development and characterization of methoxy poly(ethylene oxide)-block-poly(ε-caprolactone) (PEO-b-PCL) micelles as vehicles for the solubilization and delivery of tacrolimus. Saudi Pharm. J. 2017, 25, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Haddadi, A.; Molavi, O.; Lavasanifar, A.; Lai, R.; Samuel, J. Micelles of poly(ethylene oxide)-b-poly(ε-caprolactone) as vehicles for the solubilization, stabilization, and controlled delivery of curcumin. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2007, 86A, 300–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roizman, B.; Sears, A.E. Herpes simplex viruses and their replication. In The Human Herpesviruses; Roizman, B., Whitley, R.J., Lopez, C., Eds.; Raven Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 11–68. [Google Scholar]

- Cherry, J.; Demmler-Harrison, G.J.; Kaplan, S.L.; Steinbach, W.J.; Hotez, P.J. Feigin and Cherry’s Textbook of Pediatric Infectious Diseases 2017, PT6615.

- Pesavento, P.A.; Chang, K.O.; Parker, J.S. Molecular virology of feline calicivirus. Vet. Clin. North Am. Small Anim. Pract. 2008, 38, 775–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atanasova, M.-D.; Grancharov, G.; Petrov, P.D. Poly(ethylene oxide)-block-poly(α-cinnamyl-ε-caprolactone-co-ε-caprolactone) diblock copolymer nanocarriers for enhanced solubilization of caffeic acid phenethyl ester. J. Polym. Sci. 2021, 59, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borenfreund, E.; Puerner, J.A. Toxicity determined in vitro by morphological alterations and neutral red absorption. Toxicol. Lett. 1985, 24, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamenova, K.; Iliev, I.; Prancheva, A.; Tuleshkov, P.; Rusanov, K.; Atanassov, I.; Petrov, P.D. Hydroxypropyl cellulose hydrogel containing Origanum vulgare ssp. hirtum essential-oil-loaded polymeric micelles for enhanced treatment of melanoma. Gels 2024, 10, 627. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, L.J.; Muench, H. A simple method of estimating fifty percent endpoints. Am. J. Hyg. 1938, 27, 493–497. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Test No. 432: In Vitro 3T3 NRU Phototoxicity Test. In OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Section 4; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cytopathic Effect Inhibition Assay. Creative Diagnostics. 2025. Available online: https://antiviral.creative-diagnostics.com/cc50-ic50-assay.html (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Avram, Ș.; Bora, L.; Vlaia, L.L.; Muț, A.M.; Olteanu, G.-E.; Olariu, I.; Magyari-Pavel, I.Z.; Minda, D.; Diaconeasa, Z.; Sfirloaga, P.; et al. Cutaneous polymeric-micelles-based hydrogel containing Origanum vulgare L. essential oil: In vitro release and permeation, angiogenesis, and safety profile in ovo. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boskovic, M.; Zdravkovic, N.; Ivanovic, J.; Janjic, J.; Djordjevic, J.; Starcevic, M.; Baltic, M.Z. Antimicrobial activity of thyme (Thymus vulgaris) and oregano (Origanum vulgare) essential oils against some food-borne microorganisms. Procedia Food Sci. 2015, 5, 18–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begnini, K.R.; Nedel, F.; Lund, R.G.; Carvalho, P.H.D.A.; Rodrigues, M.R.A.; Beira, F.T.A.; Del-Pino, F.A.B. Composition and antiproliferative effect of essential oil of Origanum vulgare against tumor cell lines. J. Med. Food 2014, 17, 1129–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarikurkcu, C.; Zengin, G.; Oskay, M.; Uysal, S.; Ceylan, R.; Aktumsek, A. Composition, antioxidant, antimicrobial and enzyme inhibition activities of two Origanum vulgare subspecies (subsp. vulgare and subsp. hirtum) essential oils. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 70, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prusoff, W.H.; Lin, T.S.; Zucker, M. Potential targets for antiviral chemotherapy. Antiviral Res. 1986, 6, 311–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, P.; Bergmann, T.; Cuellar-Camacho, J.L.; Ehrmann, S.; Chowdhury, M.S.; Zhang, M.; Dahmani, I.; Haag, R.; Azab, W. Multivalent flexible nanogels exhibit broad-spectrum antiviral activity by blocking virus entry. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 6429–6442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Canady, T.D.; Zhou, Z.; Tang, Y.; Price, D.N.; Bear, D.G.; Chi, E.Y.; Schanze, K.S.; Whitten, D.G. Cationic phenylene ethynylene polymers and oligomers exhibit efficient antiviral activity. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2011, 3, 2209–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Mass Ratio | Dh (nm) | ζ-Potential (mV) | Transmittance (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEO-b-PCL micelles | - | 27 ± 5 | −8.78 ± 0.62 | 90.76 |

| OEO/PEO-b-PCL micelles | 1:5 | 39 ± 2 | −6.41 ± 1.17 | 89.95 |

| OEO/PEO-b-PCL micelles | 1:2.5 | 38 ± 5 | −6.51 ± 1.55 | 85.27 |

| OEO/PEO-b-PCL micelles | 1:1 | 69 ± 4 | −8.68 ± 0.43 | 15.07 |

| Compounds | CC50 ± SD (µg/mL) | PIF | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Irradiated | Irradiated | ||

| Blank polymer micelles | 159.59 ± 9.27 | 67.66 ± 2.91 | 2.4 |

| Oregano oil | 93.25 ± 2.02 | 90.70 ± 2.27 | 1.0 |

| Oregano oil-loaded polymer micelles | 105.05 ± 2.05 | 54.17 ± 3.22 | 1.9 |

| Chlorpromazine | 18.23 ± 0.68 | 3.17 ± 0.52 | 5.8 |

| Viral Strain | Time | Samples Concentration (µg/mL) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OEO | PMs | OEO-Loaded PMs | Acyclovir | Remdesivir | ||

| MDBK | CC50 | 294.6 ± 5.7 * | 530.4 ± 6.3 *** | 340.7 ± 5.4 *** | 291.0 ± 9.4 | nd |

| MTC | 50 | 100 | 100 | nd | nd | |

| Vero E6 | CC50 | 228.3 ± 4.6 *** | 500.0 ± 5.3 *** | 310.0 ± 4.9 *** | nd | 245.0 ± 5.6 |

| MTC | 50 | 100 | 100 | nd | nd | |

| CRFK | CC50 | 262.4 ± 4.2 | 520.5 ± 6.4 | 324.6 ± 4.4 | nd | nd |

| MTC | 50 | 100 | 100 | nd | nd | |

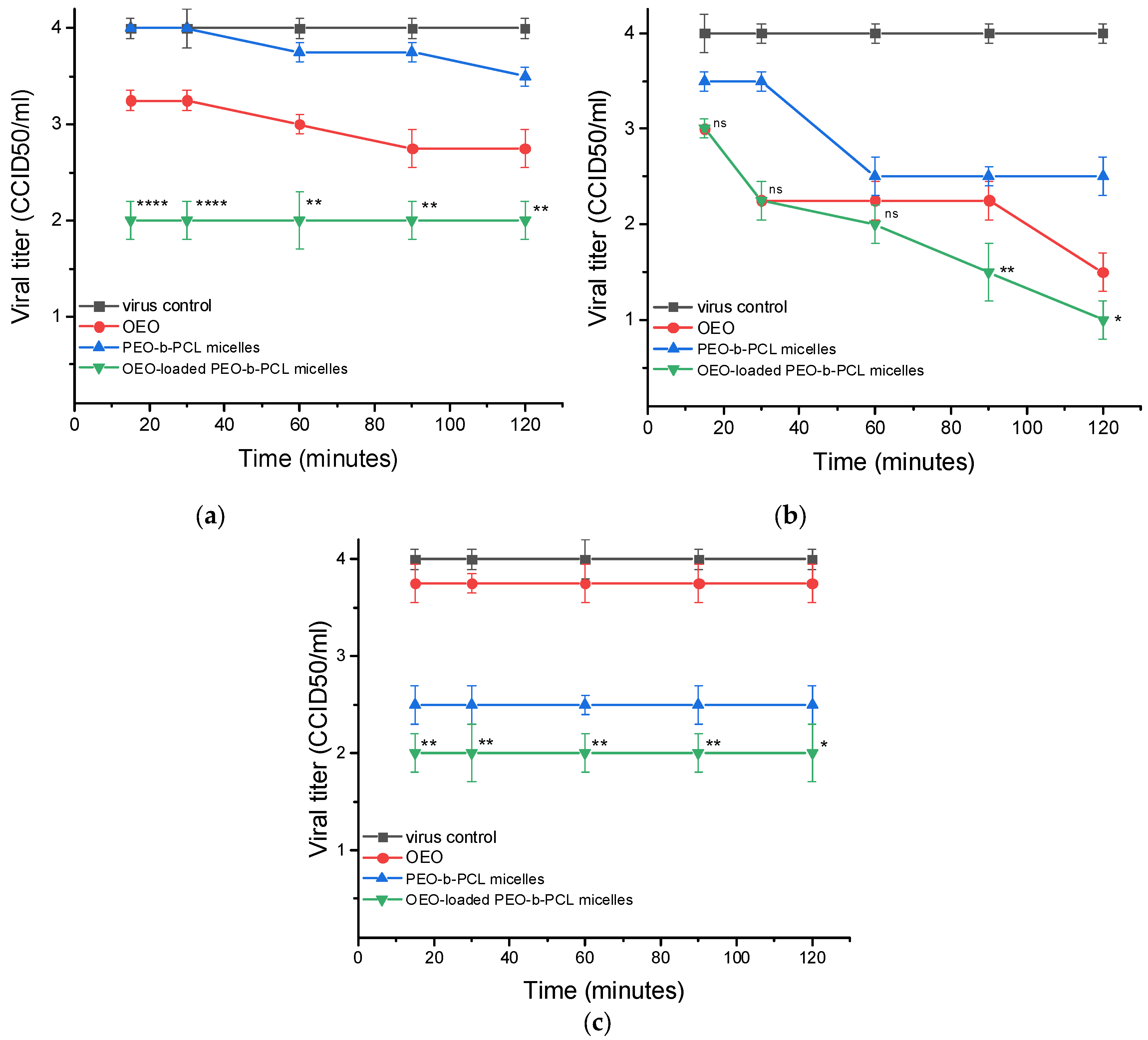

| Viral Strain | Time | Δlg ± SD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OEO | PEO-b-PCL Micelles | OEO-Loaded PEO-b-PCL Micelles | ||

| HSV-1 | 15 min | 1.75 ± 0.2 | 0.75 ± 0.1 | 2.0 ± 0.2 ns |

| 30 min | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 1.25 ± 0.1 | 2.25 ± 0.3 ns | |

| 45 min | 2.25 ± 0.3 | 1.75 ± 0.2 | 2.5 ± 0.2 ns | |

| 60 min | 2.5 ± 0.2 | 1.75 ± 0.1 | 3.0 ± 0.3 ns | |

| HCoV OC-43 | 15 min | 2.0 ± 0.3 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 2.25 ± 0.2 ns |

| 30 min | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 2.25 ± 0.2 ns | |

| 60 min | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 2.25 ± 0.2 ns | |

| 90 min | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 2.25 ± 0.3 ns | |

| 120 min | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 2.25 ± 0.2 ns | |

| FCV | 15 min | 2.5 ± 0.3 | 2.25 ± 0.2 | 2.5 ± 0.2 ns |

| 30 min | 2.75 ± 0.3 | 2.25 ± 0.3 | 2.5 ± 0.3 ns | |

| 45 min | 2.75 ± 0.2 | 2.25 ± 0.2 | 2.5 ± 0.2 ns | |

| 60 min | 2.75 ± 0.3 | 2.25 ± 0.2 | 2.75 ± 0.3 ns | |

| Viral Strain | Time | Δlg ± SD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OEO | PEO-b-PCL Micelles | OEO-Loaded PEO-b-PCL Micelles | 70% Ethanol | ||

| HSV-1 | 15 min | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 1.5 ± 0.1 ** | 5.0 ± 0.1 |

| 30 min | 1.25 ± 0.1 | 0.75 ± 0.1 | 1.5 ± 0.1 * | 5.0 ± 0.1 | |

| 60 min | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 2.0 ± 0.2 * | 5.0 ± 0.1 | |

| 90 min | 2.75 ± 0.3 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 3.5 ± 0.3 * | 5.0 ± 0.1 | |

| 120 min | 2.75 ± 0.3 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 3.5 ± 0.3 * | 5.0 ± 0.1 | |

| HCoV OC-43 | 15 min | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.75 ± 0.1 | 0.75 ± 0.1 * | 5.0 ± 0.1 |

| 30 min | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.25 ± 0.1 | 1.25 ± 0.1 * | 5.0 ± 0.1 | |

| 60 min | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 1.25 ± 0.2 | 1.75 ± 0.2 ns | 5.0 ± 0.1 | |

| 90 min | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 1.75 ± 0.2 ns | 5.0 ± 0.1 | |

| 120 min | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 2.0 ± 0.2 ** | 5.0 ± 0.1 | |

| FCV | 15 min | 2.5 ± 0.3 | 1.75 ± 0.2 | 2.0 ± 0.2 * | 5.0 ± 0.1 |

| 30 min | 2.5 ± 0.2 | 1.75 ± 0.2 | 2.0 ± 0.2 * | 5.0 ± 0.1 | |

| 60 min | 3.0 ± 0.3 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 2.25 ± 0.2 ** | 5.0 ± 0.1 | |

| 90 min | 3.0 ± 0.3 | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 2.25 ± 0.3 ** | 5.0 ± 0.1 | |

| 120 min | 3.0 ± 0.2 | 3.25 ± 0.3 | 3.5 ± 0.3 * | 5.0 ± 0.1 | |

| Viral Strain | Time | Δlg ± SD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OEO | PEO-b-PCL Micelles | OEO-Loaded PEO-b-PCL Micelles | ||

| HSV-1 | 15 min | 0.75 ± 0.1 | 0.0 | 2.0 ± 0.2 **** |

| 30 min | 0.75 ± 0.1 | 0.0 | 2.0 ± 0.2 **** | |

| 60 min | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 0.25 ± 0.1 | 2.0 ± 0.3 ** | |

| 90 min | 1.25 ± 0.2 | 0.25 ± 0.1 | 2.0 ± 0.2 ** | |

| 120 min | 1.25 ± 0.2 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 2.0 ± 0.2 ** | |

| HCoV OC-43 | 15 min | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.1 ns |

| 30 min | 1.75 ± 0.2 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 1.75 ± 0.2 ns | |

| 60 min | 1.75 ± 0.2 | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 2.0 ± 0.2 ns | |

| 90 min | 1.75 ± 0.2 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 2.5 ± 0.3 ** | |

| 120 min | 2.5 ± 0.2 | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 3.0 ± 0.2 * | |

| FCV | 15 min | 1.25 ± 0.2 | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 2.0 ± 0.2 ** |

| 30 min | 1.25 ± 0.1 | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 2.0 ± 0.3 ** | |

| 60 min | 1.25 ± 0.2 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 2.0 ± 0.2 ** | |

| 90 min | 1.25 ± 0.2 | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 2.0 ± 0.2 ** | |

| 120 min | 1.25 ± 0.2 | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 2.0 ± 0.3 * | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vilhelmova-Ilieva, N.; Iliev, I.; Kamenova, K.; Grancharov, G.; Rusanov, K.; Atanassov, I.; Petrov, P.D. Antiviral Activity of Origanum vulgare ssp. hirtum Essential Oil-Loaded Polymeric Micelles. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2417. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13102417

Vilhelmova-Ilieva N, Iliev I, Kamenova K, Grancharov G, Rusanov K, Atanassov I, Petrov PD. Antiviral Activity of Origanum vulgare ssp. hirtum Essential Oil-Loaded Polymeric Micelles. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(10):2417. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13102417

Chicago/Turabian StyleVilhelmova-Ilieva, Neli, Ivan Iliev, Katya Kamenova, Georgy Grancharov, Krasimir Rusanov, Ivan Atanassov, and Petar D. Petrov. 2025. "Antiviral Activity of Origanum vulgare ssp. hirtum Essential Oil-Loaded Polymeric Micelles" Biomedicines 13, no. 10: 2417. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13102417

APA StyleVilhelmova-Ilieva, N., Iliev, I., Kamenova, K., Grancharov, G., Rusanov, K., Atanassov, I., & Petrov, P. D. (2025). Antiviral Activity of Origanum vulgare ssp. hirtum Essential Oil-Loaded Polymeric Micelles. Biomedicines, 13(10), 2417. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13102417