Abstract

Background: Conventional treatments for cancers of the head and neck region are often associated with high recurrence rates and impaired quality of life. Photodynamic therapy (PDT) has emerged as a promising alternative, leveraging photosensitizers such as hypericin to selectively target tumour cells with minimal damage to surrounding healthy tissues. Objectives: We aimed to evaluate the efficacy and underlying mechanisms of hypericin-mediated PDT (HY-PDT) in treating head and neck cancers. Methods: Adhering to PRISMA 2020 guidelines, a systematic search was conducted across PubMed/Medline, Embase, Scopus, and the Cochrane Library for studies published between January 2000 and December 2024. Inclusion criteria encompassed preclinical in vitro and in vivo studies and clinical trials focusing on HY-PDT for head and neck malignancies and its subtypes. Results: A total of 13 studies met the inclusion criteria, comprising both in vitro and in vivo investigations. HY-PDT consistently demonstrated significant cytotoxicity against squamous cell carcinoma cells through apoptotic and necrotic pathways, primarily mediated by ROS generation. Hypericin exhibited selective uptake in cancer cells over normal keratinocytes. Additionally, HY-PDT modulated the tumour microenvironment by altering cytokine profiles, such as by increasing IL-20 and sIL-6R levels, which may enhance antitumor immunity and reduce metastasis. Conclusions: HY-PDT emerges as a highly promising and minimally toxic treatment modality for head and neck cancers, demonstrating efficacy in inducing selective tumour cell death and modulating the immune microenvironment. Despite the encouraging preclinical evidence, significant methodological variability and limited clinical data necessitate further large-scale, standardized and randomized controlled trials.

1. Introduction

1.1. Rationale

Head and neck cancers represent a heterogeneous group of malignancies in anatomically complex and functionally critical regions, such as the oral cavity, pharynx, and larynx [1]. These cancers pose significant clinical and therapeutic challenges, often leading to impaired speech, swallowing difficulties, and disfigurement, substantially affecting patients’ quality of life [2]. Conventional treatment options, such as surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy, although often effective at controlling or reducing the burden associated with tumours, are frequently associated with long-term complications, high recurrence rates, and considerable morbidity [3]. Consequently, there is an ongoing need to explore more selective, and less invasive, treatments that can improve clinical outcomes and maintain or restore function for individuals suffering from these diseases [4]. Photodynamic therapy (PDT) has emerged as a promising treatment for various cancers, including those of the head and neck region [5]. PDT involves the administration of a photosensitizing agent that preferentially accumulates in tumour cells, followed by irradiation with a specific wavelength of light [6]. This interaction generates reactive oxygen species (ROS) that cause oxidative damage to cellular components, ultimately leading to tumour cell death [6]. Moreover, beyond the direct cytotoxic damage resulting from ROS generation, PDT also exerts its therapeutic effects by acting on the tumour vasculature that causes vascular shutdown, reduced blood flow, and consequent ischemic cell death and by triggering a range of immunomodulatory mechanisms. These include the release of tumour-associated antigens, recruitment of immune effector cells, and alteration of cytokine profiles, all of which can collectively enhance systemic anti-tumour immunity [7].

Unlike traditional cancer treatments, PDT offers the advantage of spatial selectivity—light can be directed precisely to the tumour site—thereby minimizing harm to surrounding healthy tissues [4,5,6]. Additionally, PDT has been reported to provoke immunomodulatory effects, potentially enhancing anti-tumour immunity and reducing the likelihood of metastasis and recurrence [7]. Within the spectrum of available photosensitizers, hypericin has gathered significant attention for its unique chemical and photophysical properties [8,9]. Brancaleon and Moseley have demonstrated that endoscopy, combined with light irradiation, can effectively excite photosensitizers [10]. Lasers are widely used for superficial and interstitial PDT due to their monochromatic nature, coherent light, high optical power, and ability to tune wavelengths to match specific photosensitizers [11]. Their narrow, collimated beams are often coupled with optical fibres for endoscopic or interstitial applications [11].

Hypericin is a naturally occurring compound primarily isolated from Hypericum perforatum (St. John’s Wort), a plant with a long history of therapeutic applications [8]. Its ability to accumulate within cellular compartments, such as mitochondria and the endoplasmic reticulum, makes it highly effective in disrupting critical cellular functions [9]. Preclinical studies have shown that hypericin-based PDT can induce apoptosis, necrosis, and other forms of cell death in malignant cells [12]. Additionally, hypericin-mediated PDT (HY-PDT) has demonstrated potential advantages over certain conventional treatments, including reduced systemic toxicity and a more favourable safety profile [13]. As research into HY-PDT has grown, investigations have extended into its immunomodulatory effects. Beyond direct cytotoxicity, hypericin’s photoactivated state may influence cytokine production, affect tumour-associated immune cells, and modulate inflammatory responses [14]. These immunological alterations could enhance tumour control, reduce metastatic potential, and improve long-term clinical outcomes [14,15,16,17,18].

1.2. Objectives

The primary aim of this systematic review is to provide a synthesis of the existing literature on HY-PDT for head and neck cancers. We seek to determine the efficacy of HY-PDT in reducing tumour burden as well as improving survival. It is important to also explore the underlying mechanisms of action, including the generation of ROS and subsequent immunological responses that may contribute to enhanced therapeutic outcomes as well as to compare HY-PDT to alternative or established therapies, evaluating its potential clinical applications. In doing so, this review will identify knowledge gaps, highlight areas for future research, and provide evidence-based guidance for clinicians and researchers aiming to advance the treatment of head and neck cancers through HY-PDT.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Focused Question and Null Hypothesis

A systematic review was conducted using the PICO framework to evaluate the efficacy of hypericin-mediated photodynamic therapy for head and neck cancers [19]. The research focused on patients diagnosed with cancer of the head and neck region (Population). The review examined whether treatment with HY-PDT (Intervention), in comparison with other approaches such as light irradiation alone, use of hypericin without light activation, or alternative cancer therapies (Comparison), results in improved tumour reduction, immunomodulatory effects, or cell viability reduction (Outcome). The null hypothesis is that there is no significant difference in the effectiveness of HY-PDT compared with alternative treatments for reducing tumour size, modulating the immune response, or inducing cellular apoptosis.

2.2. Search Strategy

This systematic review, registered in the PROSPERO database under ID CRD42024627236, was conducted in adherence to the PRISMA 2020 guidelines [20]. A comprehensive electronic search was carried out across PubMed/Medline, Embase, Scopus, and the Cochrane Library (details of search terms provided in Table 1). Three authors (J.F.-R., N.Z. and R.T.) independently searched four databases using predefined standardized terms. The results were filtered to include studies published in English between 1 January 2000 and 3 December 2024. The authors chose to include older studies, as their conclusions were deemed relevant to this day and no similar research had been carried out since that time. Initial screening was performed by reviewing titles and abstracts in order to identify studies meeting the inclusion criteria (outlined in Table 2). The inclusion and exclusion criteria for study selection were rigorously applied to ensure the relevance and quality of the reviewed literature. Subsequently, two authors (J.F.-R. and N.Z.) conducted an in-depth review of the full texts to extract relevant data. A snowballing technique was also applied, examining reference lists of eligible articles to identify additional relevant studies, but no additional articles were found.

Table 1.

Search syntax used in the study.

Table 2.

Selection criteria for papers included in the systematic review.

2.3. Selection of Studies

In the study selection phase of this systematic review, three reviewers (J.F.-R., N.Z. and R.W.) conducted independent assessments of the titles and abstracts from the identified articles to reduce potential bias. Discrepancies in study eligibility were addressed through thorough deliberation among the reviewers until consensus was reached. By following a process aligned with the PRISMA guidelines, the review prioritized the inclusion of highly relevant and methodologically robust studies, enhancing the overall reliability and replicability of the findings [20].

2.4. Risk of Bias in Individual Studies

In the initial phase of study selection, three reviewers (J.F.-R., N.Z. and M.M.) independently assessed the titles and abstracts of the identified articles to mitigate potential bias. To ensure consistency in evaluations, inter-reviewer agreement was quantified using Cohen’s kappa statistic [21]. Any conflicts regarding the inclusion or exclusion of studies were resolved through comprehensive discussions among the authors, ultimately reaching a unanimous consensus.

2.5. Quality Assessment

The quality of the included studies on HY-PDT for head and neck carcinomas was independently assessed by three reviewers (J.F.-R., N.Z. and M.M.). The evaluation focused on critical aspects of PDT design, execution, and reporting, specifically regarding the use of hypericin. The objectivity and reproducibility of the results were prioritized. The risk of bias was assessed using the following criteria, with a score of 1 for “yes” and 0 for “no”, as follows:

- Was the specific concentration of hypericin as the photosensitizer clearly indicated?

- Was the origin or source of the hypericin provided?

- Was the incubation time for the hypericin clearly stated?

- Were detailed light source parameters (type, wavelength, energy density, fluence, and power density) reported?

- Was a power meter used to verify the light parameters?

- Was a negative control group included in the experimental design?

- Were numerical results reported with relevant statistical analyses?

- Was there a clear method for addressing missing outcome data?

- Was the study free from potential conflicts of interest related to its source of funding?

Studies were categorized based on the total number of affirmative (“yes”) responses to the following criteria: high risk of bias: 0–3; moderate risk of Bias: 4–6; low risk of bias: 7–9. Each study’s results were analysed to assign a corresponding bias classification—low, moderate, or high. The methodology for assessing the risk of bias adhered to the recommendations outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [22]. This framework ensures a comprehensive and systematic evaluation of the included studies.

2.6. Risk of Bias Across Studies and Quality Assessment Presentation

Table 3 presents the results of the risk of bias assessment for each of the 13 studies included after full-text review. To qualify for inclusion, studies needed to have achieved a minimum score of 6. All selected studies were determined to have a low or moderate risk of bias, with three achieving the highest possible score of 9 [23,24,25].

Table 3.

The results of the quality assessment and risk of bias across the studies.

2.7. Data Extraction

Once the selection of articles was finalized through consensus, three reviewers (J.F.-R., M.M. and R.W.) systematically extracted data on multiple parameters. These included citation details (author names and year of publication), study design, type of cancer examined, characteristics of the experimental and control groups, follow-up durations, reported outcomes, specifications of the light source, concentrations of hypericin, laser parameters, as well as details on incubation and irradiation durations.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

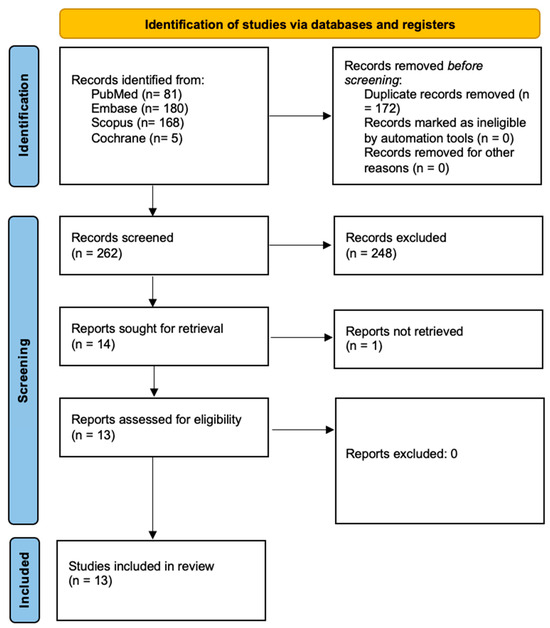

Figure 1 outlines the research process conducted in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines [20]. The initial database search identified 434 articles, which were reduced to 262 after removing duplicates. Screening the titles and abstracts resulted in 14 studies being deemed eligible for full-text assessment. Of these, one study was excluded, as the full text had been removed by the authors. Ultimately, 13 studies, all published within the past 25 years, were included in the final analysis. A detailed summary of these studies is provided in Table 4.

Figure 1.

Prisma 2020 flow diagram [20].

Table 4.

A general overview of the studies.

3.2. General Characteristics of the Included Studies

Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7 provide a detailed summary of the data extracted from the studies that fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were incorporated into the review. The summaries include key information on the overall characteristics of the studies, technical details of the light sources utilized, and the properties of hypericin as photosensitizer in photodynamic therapy protocols.

Table 5.

Main outcomes and details from each study.

Table 6.

Physical parameters of light sources.

Table 7.

Characteristics of PS used in studies meeting eligibility criteria.

3.3. Main Study Outcomes

HY-PDT has shown potential in cancer treatment due to its ability to generate ROS upon activation by specific wavelengths of light, leading to tumour cell death through apoptosis, necrosis, or both. Studies by Bhuvaneswari et al. (2007) explored hypericin’s efficacy in various cancer types, including nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC), head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, oral squamous cell carcinoma, melanoma, and other solid tumours [26]. With regard to NPC, Bhuvaneswari et al. have demonstrated that PDT triggers hypoxia within tumours, leading to vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) upregulation via the HIF-1α pathway. This effect can be mitigated with celebrex, a COX-2 inhibitor, which downregulates VEGF expression, potentially preventing tumour regrowth and enhancing PDT outcomes. Blank et al. (2001) highlighted HY-PDT’s effectiveness in inducing extensive tumour necrosis and inflammation in highly invasive solid tumours, although systemic immune antitumoral responses remain limited [27]. Research into the biodistribution and phototoxicity of hypericin, as investigated by Du et al. (2003), demonstrates its optimal activation at wavelengths around 593 nm, corresponding to its absorption peaks [29,30,31]. Hypericin accumulates predominantly in tumour cells, with localization in organelles such as the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus [31]. Tumour regression is most effective when light irradiation is applied at peak tumour uptake times, such as six hours post-hypericin injection, as shown in Du et al. (2003) [29,30,31].

In vitro studies by Laffers et al. (2015) confirm hypericin’s ability to induce apoptosis at low concentrations and short light exposures, while in vivo applications show significant tumour regression in smaller tumours and partial responses in larger ones [34]. However, the therapy’s efficacy is challenged by limited light penetration, particularly in larger tumours, and potential off-target effects, as noted by Olek et al. (2023), who have reported cytotoxicity in healthy fibroblasts and keratinocytes [23]. PDT’s immunomodulatory effects have been highlighted by Olek et al. (2024), with reports of alterations in cytokine secretion [24]. For example, HY-PDT increases pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-8 and IL-6 in cancer cells, while reducing immunosuppressive factors such as PTX3. Despite these effects, systemic immune responses remain underwhelming, with limited activation of antitumoral immunity, as suggested by Du et al. (2002) [29]. Furthermore, studies investigating hypericin-mediated PDT in cell lines, such as those by Xu et al. (2010), reveal varying responses depending on the tumour microenvironment, emphasizing the need for tailored therapeutic approaches [25]. Selectivity for cancer cells has been observed, particularly in melanoma and squamous cell carcinoma, where Wozniak et al. (2023) have demonstrated hypericin’s preferential accumulation in malignant cells [35]. However, hypericin’s poor solubility and sensitivity to environmental factors remain significant barriers to clinical application [35]. Advances in laser technology, combination therapies, and drug delivery systems, as noted by Sharma et al. (2012), are critical to addressing current limitations, such as suboptimal light penetration, off-target effects, and inadequate immune responses [33]. Future research, as recommended by Head et al. (2006) and others, must focus on optimizing dosing regimens, light parameters, and drug formulations to enhance therapeutic efficacy and minimize adverse effects, paving the way for hypericin-based PDT to become a more reliable and widely adopted cancer treatment modality [32]. Table 5 summarises the outcomes of each study.

Hypericin preferentially accumulates in tumours due to increased vascular permeability and active cellular uptake of hydrophobic molecules [30,31,35]. Studies show peak tumour uptake occurs hours post-injection, guiding irradiation timing to maximize tumour-to-healthy tissue concentration ratios [30,31,35]. Immune cells, especially neutrophils, may internalize hypericin in the tumour microenvironment, potentially enhancing antitumor activity or sensitizing them to oxidative stress [27]. Hypericin localizes to organelles like the ER, Golgi, and mitochondria, triggering apoptosis or necrosis [22,31,34]. Hypericin’s advantages over other photosensitizers include strong absorption peaks (545–595 nm), high singlet oxygen quantum yield, low dark toxicity, and immunomodulatory effects like cytokine profile modulation (e.g., IL-8, IL-20, TNF-α receptors) [24,27,28,35]. These features make hypericin promising for photodynamic therapy (PDT), particularly in head and neck cancers [28,35]. Hypericin retains characteristic absorption (~470, 545, 595 nm) and fluorescence (~590, 640 nm) spectra in cells and tumours, enabling fluorescence imaging for localization and efficacy monitoring [28,30,32]. Effective PDT is achieved with micromolar hypericin concentrations (0.5–5 µM) and moderate light fluences (3–20 J/cm2), favouring apoptosis over necrosis [25,34,35]. Excessive hypericin or light doses shift responses toward necrosis, highlighting the need for parameter optimization [34,35]. During hypericin-mediated PDT, reactive oxygen species, like singlet oxygen, superoxide, and hydroxyl radicals, induce oxidative damage in organelles, driving apoptosis or necrosis [28,31,35]. Hypericin-mediated PDT also disrupts tumour vasculature, creating transient hypoxia. Combining hypericin-mediated PDT with celecoxib blocks the COX-2/HIF-1α/VEGF pathway, mitigating hypoxia-driven VEGF rebound and improving tumour control [26].

3.4. Characteristics of Light Sources Used in PDT

4. Discussion

4.1. Results in the Context of Other Evidence

This systematic review provides enough evidence to reject the null hypothesis. HY-PDT demonstrates significant preclinical promise as a selective and minimally toxic therapeutic option for head and neck cancers, showing efficacy in inducing tumour cell death (via apoptosis and necrosis), modulating the immune microenvironment, and offering potential advantages over conventional therapies. HY-PDT generates ROS that induces both apoptotic and necrotic cell death in head and neck cancer cells [25,26,34]. Cancer cells such as SCC-25 demonstrate enhanced sensitivity to hypericin compared with normal cells, emphasizing the selective cytotoxic potential of HY-PDT [31,33,35]. This therapy also influences the tumour microenvironment by altering cytokine production, including IL-8 and IL-20, which can modulate immune responses and impact tumour progression [23,24,29]. When combined with agents like celecoxib, HY-PDT can significantly downregulate pro-angiogenic factors such as VEGF, potentially preventing tumour regrowth [26,27]. Optimal therapeutic outcomes depend on the precise control of parameters, including wavelength, intensity, and duration of light exposure, while treatment efficacy decreases with larger tumour sizes due to limitations in light penetration [25,28,32,33]. Despite these challenges, HY-PDT maintains relatively localized cytotoxicity with minimal systemic toxicity, and its immunomodulatory effects—stemming from altered cytokine expression and influences on tumour-associated immune cells—further support its role as a promising treatment modality [23,24,27,30,34,35]. Mechanistically, hypericin localizes within cellular organelles such as mitochondria, causing substantial structural damage and promoting tumour cell death [28,34]. Although further clinical studies are necessary, the accumulating evidence suggests that HY-PDT holds considerable promise as a therapeutic approach for head and neck cancers [24,30,33]. Numerous studies have come to similar conclusions. Several studies have evaluated the application of PDT in other malignancies. Dong et al. have demonstrated that HY-PDT holds considerable potential as a precision cancer therapy by engaging molecular pathways to initiate apoptosis, necrosis, and autophagy. However, further inquiry is necessary in order to address obstacles, such as limited bioavailability, and to enhance its clinical implementation [36].

Kamuhabwa et al. have provided evidence that HY-PDT can trigger either apoptosis or necrosis in AY-27 urinary bladder carcinoma cells, depending on the concentration used. These findings suggest that hypericin-based photodynamic therapy may play a crucial role in treating superficial bladder carcinoma [37]. Zupko et al. have demonstrated that, in AY-27 tumours, the primary mechanism of HYP-PDT involves altering the tumour vasculature rather than causing direct cellular damage [38]. Huygens et al. have demonstrated that the combination of hypericin and hyperoxygenation can nearly eradicate RT-112 bladder cancer cells through apoptotic mechanisms [39]. In another study, Blank et al. investigated the impact of varying wavelengths in HYP-PDT for C26 colon carcinoma cells and found that in vitro irradiation of hypericin-sensitized cells reduced cell viability in a dose-dependent manner [40]. Ferenc et al. have reported that employing HYP-PDT together with genistein impaired the proliferation of MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells and promoted their apoptosis [41]. Furthermore, Delaey et al. were the first to establish that hypericin-induced photocytotoxicity in HeLa cells is influenced by cell density, as sparse cultures displayed greater sensitivity to PDT compared with confluent cell layers [42]. Photodynamic therapy offers a means of controlling the proliferation of glioma cells, a notably invasive category of cancers. In a groundbreaking study, Miccoli et al. found that photoactivation of hypericin disrupted the energy metabolism of SNB-19 glioma cells by preventing hexokinase from anchoring to the mitochondria [43]. These findings indicate that hypericin may serve as a potent phototoxic agent against glioma tumours [43,44]. Lavie et al. have demonstrated that the photoactivation of HYP and dimethyl tetrahydroxyhelianthrone (DTHe) induces both apoptotic and necrotic cell death in HL-60 and K-562 cells, accompanied by nucleolar chromatin condensation [45]. Liu’s work has revealed that HYP-PDT markedly inhibits the proliferation of MiaPaCa-2 and PANC-1 pancreatic cancer cells both in vivo and in vitro, suggesting that hypericin-based photodynamic therapy could be an effective treatment strategy for this malignancy [46]. In related research, Chen et al. have shown that HYP-PDT can induce vascular damage and apoptosis within a radiation-induced fibrosarcoma-1 mouse tumour model [47]. These findings highlight the broad therapeutic promise of hypericin-based photodynamic therapy as a versatile and effective treatment modality against a wide spectrum of malignancies.

Beyond direct cytotoxicity, HY-PDT influences antitumor immunity by modulating inflammatory pathways. Studies report changes in cytokine profiles, such as IL-8 and soluble TNF receptors, in tumour microenvironments, impacting local inflammation and systemic immune responses [23,24,27,29]. While HY-PDT triggers tumour necrosis and inflammation, systemic immune activation remains limited, reflecting the complexity of immune responses across tumour models. These findings highlight HY-PDT’s ability to reshape tumour-related immune pathways, enhancing its therapeutic potential. Picosecond pulsed laser irradiation enhances HY-PDT efficacy compared with nanosecond pulses by increasing ROS generation and improving the subcellular targeting of organelles like mitochondria and the ER [28,34,35]. Shorter pulse durations enable deeper tissue penetration, reduce thermal diffusion, and minimize damage to healthy tissues, improving selectivity and safety. Picosecond pulses also amplify vascular disruption and immunomodulatory effects, further boosting antitumor immune responses.

Optimizing pulse duration is an important parameter when maximizing therapeutic outcomes in HY-PDT. Hypericin presents several advantages over conventional photosensitizers, such as photofrin and aminolevulinic acid in PDT, which include stronger absorption peaks, higher singlet oxygen quantum yields, lower dark toxicity, and selective tumour accumulation, and which increase cytotoxicity to the cells while minimizing off-target effects [28,31,34,35]. Additionally, hypericin’s immunomodulatory properties, such as cytokine modulation, contribute to antitumor immunity, unlike many traditional photosensitizers [23,24,27]. While hypericin faces challenges, like poor solubility, chemical modifications and delivery systems address these limitations, solidifying its role as a promising alternative in PDT [23,24,25,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35]. Chemical modifications to hypericin improve solubility, stability, and targeting capabilities. Strategies include conjugation with antibodies or peptides for selective uptake, encapsulation in nanoparticles for controlled release, and PEGylation to enhance bioavailability [28,35].

4.2. Limitations of the Evidence

While the review synthesizes compelling evidence for HY-PDT, several limitations in the available literature were identified. Most studies are preclinical, with limited in vivo and clinical data, restricting the ability to generalize findings to human populations. Furthermore, methodological heterogeneity—such as variations in hypericin concentration, light source parameters, and treatment protocols—complicates direct comparisons and meta-analytic assessments. The relatively small sample sizes and short follow-up periods in many studies further constrain the ability to evaluate long-term outcomes, including survival rates and recurrence. Studies lacked comprehensive data on the safety profile and adverse effects of HY-PDT.

4.3. Limitations of the Review Process

The significant variability among the included studies necessitated a narrative approach to synthesizing the findings. Differences in study designs, intervention strategies, and outcome measures may have introduced bias into the overall evaluation of HY-PDT. Additionally, the substantial heterogeneity in parameters precluded the use of the GRADE framework, making it challenging to formulate robust, evidence-based recommendations. Future investigations should prioritize well-structured randomized controlled trials featuring direct comparisons of key parameters and standardized treatment protocols. Excluding non-English publications and grey literature likely narrowed the scope of this review, potentially omitting valuable insights. These constraints highlight the pressing need for more standardized and harmonized research to enable systematic comparisons and comprehensive quantitative analyses.

4.4. Implications for Practice, Policy, and Future Research

Clinicians may consider integrating HY-PDT into treatment protocols, especially for patients who are poor candidates for surgery or systemic therapies. However, careful parameter optimization is critical to ensure effective tumour targeting while minimizing harm to healthy tissues. Policymakers and professional organizations could consider developing preliminary guidelines for HY-PDT use in head and neck cancers. Such guidelines would benefit from standardized reporting of treatment parameters and outcomes, ultimately shaping future clinical trials and informing evidence-based policies that encourage broader adoption once safety and efficacy are conclusively demonstrated. Regulatory agencies and research bodies should support efforts to standardize HY-PDT protocols, including photosensitizer concentrations, light delivery methods, and treatment schedules. Establishing uniform standards will facilitate meaningful comparisons across studies, accelerate the generation of high-quality evidence, and streamline the regulatory approval process for HY-PDT-based interventions. Further research should focus on large-scale, multicentre, and well-controlled randomized clinical trials that incorporate consistent treatment parameters and long-term follow-up. It is important to note that most of these studies are preclinical, and implementing laser technology in the nasopharynx presents significant logistical challenges. Studies exploring combination strategies with immunomodulatory agents, improved photosensitizer formulations for enhanced tissue penetration, and advanced imaging techniques for treatment guidance will be critical. Additionally, investigating biomarkers predictive of response could help tailor HY-PDT to individual patient profiles, ultimately improving treatment efficacy and patient outcomes. While the reviewed studies have generally reported minimal systemic toxicity, the observed cytotoxicity to healthy fibroblasts and the potential for inflammatory responses from necrotic cell death underscore the need for careful parameter optimization and detailed adverse event reporting in future studies.

5. Conclusions

This systematic review highlights the considerable potential of hypericin-mediated photodynamic therapy as a promising treatment modality for head and neck cancers. The preclinical and limited clinical data indicate that HY-PDT exerts potent cytotoxic effects on malignant cells, mediated through the generation of reactive oxygen species and leading to both apoptotic and necrotic cell death. Notably, hypericin displays preferential uptake and toxicity toward cancer cells compared with normal keratinocytes, suggesting a favourable therapeutic index. Beyond its direct cytotoxicity, HY-PDT can modulate the tumour microenvironment by influencing cytokine profiles and inflammatory mediators, thus potentially enhancing antitumor immune responses and reducing the likelihood of recurrence. Additionally, combination strategies—such as co-administration with COX-2 inhibitors—may improve treatment outcomes by downregulating pro-angiogenic factors like VEGF, potentially inhibiting tumour regrowth. Despite these encouraging findings, several challenges must be addressed before HY-PDT can be widely integrated into clinical practice. A key limitation is the anatomy of the pharynx and the associated difficult access.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.F.-R., N.Z., M.M. and R.W.; methodology, R.T. and M.M.; software, R.T. and J.F.-R.; formal analysis, J.F.-R., R.T. and N.Z.; investigation, J.F.-R., N.Z. and R.T.; writing—original draft preparation, J.F.-R., N.Z., R.T. and M.M.; writing—review and editing, N.Z., J.F.-R., R.T., R.W. and M.M.; supervision, R.W. and M.M.; funding acquisition, R.W. and M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this work the authors used Grammarly in order to improve the grammar and structure of the work. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Argiris, A.; Karamouzis, M.V.; Raben, D.; Ferris, R.L. Head and neck cancer. Lancet 2008, 371, 1695–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Raber-Durlacher, J.E.; Brennan, M.T.; Leeuw, I.M.V.-D.; Gibson, R.J.; Eilers, J.G.; Waltimo, T.; Bots, C.P.; Michelet, M.; Sollecito, T.P.; Rouleau, T.S.; et al. Swallowing dysfunction in cancer patients. Care Cancer 2012, 20, 433–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Baskar, R.; Lee, K.A.; Yeo, R.; Yeoh, K.W. Cancer and radiation therapy: Current advances and future directions. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2012, 9, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rueda, J.R.; Solà, I.; Pascual, A.; Subirana Casacuberta, M. Non-invasive interventions for improving well-being and quality of life in patients with lung cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2011, 2011, CD004282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kim, T.E.; Chang, J.E. Recent Studies in Photodynamic Therapy for Cancer Treatment: From Basic Research to Clinical Trials. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Correia, J.H.; Rodrigues, J.A.; Pimenta, S.; Dong, T.; Yang, Z. Photodynamic Therapy Review: Principles, Photosensitizers, Applications, and Future Directions. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Aebisher, D.; Woźnicki, P.; Bartusik-Aebisher, D. Photodynamic Therapy and Adaptive Immunity Induced by Reactive Oxygen Species: Recent Reports. Cancers 2024, 16, 967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiruppathi, J.; Vijayan, V.; Park, I.K.; Lee, S.E.; Rhee, J.H. Enhancing cancer immunotherapy with photodynamic therapy and nanoparticle: Making tumor microenvironment hotter to make immunotherapeutic work better. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1375767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang, X.; Wang, L.; Fekrazad, R.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, X.; He, G.; Wen, X. Polyphenolic natural products as photosensitizers for antimicrobial photodynamic therapy: Recent advances and future prospects. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1275859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Brancaleon, L.; Moseley, H. Laser and non-laser light sources for photodynamic therapy. Lasers Med. Sci. 2002, 17, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.M.; Darafsheh, A. Light Sources and Dosimetry Techniques for Photodynamic Therapy†. Photochem. Photobiol. 2020, 96, 280–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buytaert, E.; Callewaert, G.; Hendrickx, N.; Scorrano, L.; Hartmann, D.; Missiaen, L.; Vandenheede, J.R.; Heirman, I.; Grooten, J.; Agostinis, P. Role of endoplasmic reticulum depletion and multidomain proapoptotic BAX and BAK proteins in shaping cell death after hypericin-mediated photodynamic therapy. FASEB J. Off. Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. 2006, 20, 756–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansoori, B.; Mohammadi, A.; Amin Doustvandi, M.; Mohammadnejad, F.; Kamari, F.; Gjerstorff, M.F.; Baradaran, B.; Hamblin, M.R. Photodynamic therapy for cancer: Role of natural products. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2019, 26, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Deng, B.; Wang, K.; Zhang, L.; Qiu, Z.; Dong, W.; Wang, W. Photodynamic Therapy for Inflammatory and Cancerous Diseases of the Intestines: Molecular Mechanisms and Prospects for Application. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2023, 19, 4793–4810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kciuk, M.; Yahya, E.B.; Mohamed, M.M.I.; Rashid, S.; Iqbal, M.O.; Kontek, R.; Abdulsamad, M.A.; Allaq, A.A. Recent Advances in Molecular Mechanisms of Cancer Immunotherapy. Cancers 2023, 15, 2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cha, J.H.; Chan, L.C.; Song, M.S.; Hung, M.C. New Approaches on Cancer Immunotherapy. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2020, 10, a036863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Edwards, S.C.; Hoevenaar, W.H.M.; Coffelt, S.B. Emerging immunotherapies for metastasis. Br. J. Cancer 2021, 124, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mirza, F.N.; Khatri, K.A. The use of lasers in the treatment of skin cancer: A review. J. Cosmet. Laser Ther. 2017, 19, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schardt, C.; Adams, M.B.; Owens, T.; Keitz, S.; Fontelo, P. Utilization of the PICO Framework to Improve Searching PubMed for Clinical Questions. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2007, 7, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, P.F.; Petrie, A. Method Agreement Analysis: A Review of Correct Methodology. Theriogenology 2010, 73, 1167–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M. Welch Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.4; Cochrane: London, UK, 2023; Available online: www.training.cochrane.org/handbook (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- Olek, M.; Machorowska-Pieniążek, A.; Czuba, Z.P.; Cieślar, G.; Kawczyk-Krupka, A. Effect of hypericin-mediated photodynamic therapy on the secretion of soluble TNF receptors by oral cancer cells. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olek, M.; Machorowska-Pieniążek, A.; Czuba, Z.P.; Cieślar, G.; Kawczyk-Krupka, A. Immunomodulatory effect of hypericin-mediated photodynamic therapy on oral cancer cells. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.S.; Leung, A.W.N. Light-activated hypericin induces cellular destruction of nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells. Laser Phys. Lett. 2010, 7, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuvaneswari, R.; Gan, Y.Y.-Y.; Yee, K.K.L.; Soo, K.C.; Olivo, M. Effect of hypericin-mediated photodynamic therapy on the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in human nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2007, 20, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blank, M.; Lavie, G.; Mandel, M.; Keisari, Y. Effects of photodynamic therapy with hypericin in mice bearing highly invasive solid tumors. Oncol. Res. 2001, 12, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bublik, M.; Head, C.; Benharash, P.; Paiva, M.; Eshraghi, A.; Kim, T.; Saxton, R. Hypericin and pulsed laser therapy of squamous cell cancer in vitro. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2006, 24, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Bay, B.H.; Mahendran, R.; Olivo, M. Endogenous expression of interleukin-8 and interleukin-10 in nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells and the effect of photodynamic therapy. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2002, 10, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, H.Y.; Bay, B.H.; Olivo, M. Biodistribution and photodynamic therapy with hypericin in a human NPC murine tumor model. Int. J. Oncol. 2003, 22, 1019–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, H.Y.; Olivo, M.; Tan, B.K.; Bay, B.H. Photoactivation of hypericin down-regulates glutathione S-transferase activity in nasopharyngeal cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2004, 207, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Head, C.S.; Luu, Q.; Sercarz, J.; Saxton, R. Photodynamic therapy and tumor imaging of hypericin-treated squamous cell carcinoma. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2006, 4, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, K.V.; Davids, L.M. Hypericin-PDT-induced rapid necrotic death in human squamous cell carcinoma cultures after multiple treatments. Redox Lab. 2023, 12, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laffers, W.; Busse, A.-C.; Mahrt, J.; Nguyen, P.; Gerstner, A.O.H.; Bootz, F.; Wessels, J.T. Photosensitizing effects of hypericin on head neck squamous cell carcinoma in vitro. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2015, 272, 711–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wozniak, M.; Nowak-Perlak, M. Hypericin-based photodynamic therapy displays higher selectivity and phototoxicity towards melanoma and squamous cell cancer compared to normal keratinocytes in vitro. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, X.; Dong, X.; Zeng, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Fu, J.; Fu, J.; You, L.; You, L.; et al. Hypericin-mediated photodynamic therapy for the treatment of cancer: A review. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2021, 73, 425–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamuhabwa, A.R.; Agostinis, P.M.; D’Hallewin, M.-A.; Baert, L.; de Witte, P.A.M. Cellular photodestruction induced by hypericin in AY-27 rat bladder carcinoma cells. Photochem. Photobiol. 2001, 74, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zupko, I.; Kamuhabwa, A.R.; D’Hallewin, M.-A.; Baert, L.; De Witte, P.A. In vivo photodynamic activity of hypericin in transitional cell carcinoma bladder tumors. Int. J. Oncol. 2001, 18, 1099–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huygens, A.; Kamuhabwa, A.R.; Van Laethem, A.; Roskams, T.; Van Cleynenbreugel, B.; Van Poppel, H.; Agostinis, P.; De Witte, P.A. Enhancing the photodynamic effect of hypericin in tumour spheroids by fractionated light delivery in combination with hyperoxygenation. Int. J. Oncol. 2005, 26, 1691–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blank, M.; Kostenich, G.; Lavie, G.; Kimel, S.; Keisari, Y.; Orenstein, A. Wavelength-dependent properties of photodynamic therapy using hypericin in vitro and in an animal model. Photochem. Photobiol. 2002, 76, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferenc, P.; Solár, P.; Kleban, J.; Mikeš, J.; Fedoročko, P. Down-regulation of Bcl-2 and Akt induced by combination of photoactivated hypericin and genistein in human breast cancer cells. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2010, 98, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delaey, E.M.; Vandenbogaerde, A.L.; Agostinis, P.; De Witte, P.A. Confluence dependent resistance to photo-activated hypericin in HeLa cells. Int. J. Oncol. 1999, 14, 759–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miccoli, L.; Beurdeley-Thomas, A.; De Pinieux, G.; Sureau, F.; Oudard, S.; Dutrillaux, B.; Poupon, M.F. Light-induced photoactivation of hypericin affects the energy metabolism of human glioma cells by inhibiting hexokinase bound to mitochondria. Cancer Res. 1998, 58, 5777–5786. [Google Scholar]

- Uzdensky, A.B.; Ma, L.W.; Iani, V.; Hjortland, G.O.; Steen, H.B.; Moan, J. Intracellular localisation of hypericin in human glioblastoma and carcinoma cell lines. Lasers Med. Sci. 2001, 16, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavie, G.; Kaplinsky, C.; Toren, A.; Aizman, I.; Meruelo, D.; Mazur, Y.; Mandel, M. A photodynamic pathway to apoptosis and necrosis induced by dimethyl tetrahydroxyhelianthrone and hypericin in leukaemic cells: Possible relevance to photodynamic therapy. Br. J. Cancer 1999, 79, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.D.; Kwan, D.; Saxton, R.E.; McFadden, D.W. Hypericin and photodynamic therapy decreases human pancreatic cancer in vitro and in vivo. J. Surg. Res. 2000, 93, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, B.; Roskams, T.; Xu, Y.; Agostinis, P.; de Witte, P. Photodynamic therapy with hypericin induces vascular damage and apoptosis in the RIF-1 mouse tumor model. Int. J. Cancer 2002, 98, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).