Preliminary Effect and Acceptability of an Intervention to Improve End-of-Life Care in Long-Term-Care Facilities: A Feasibility Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Method

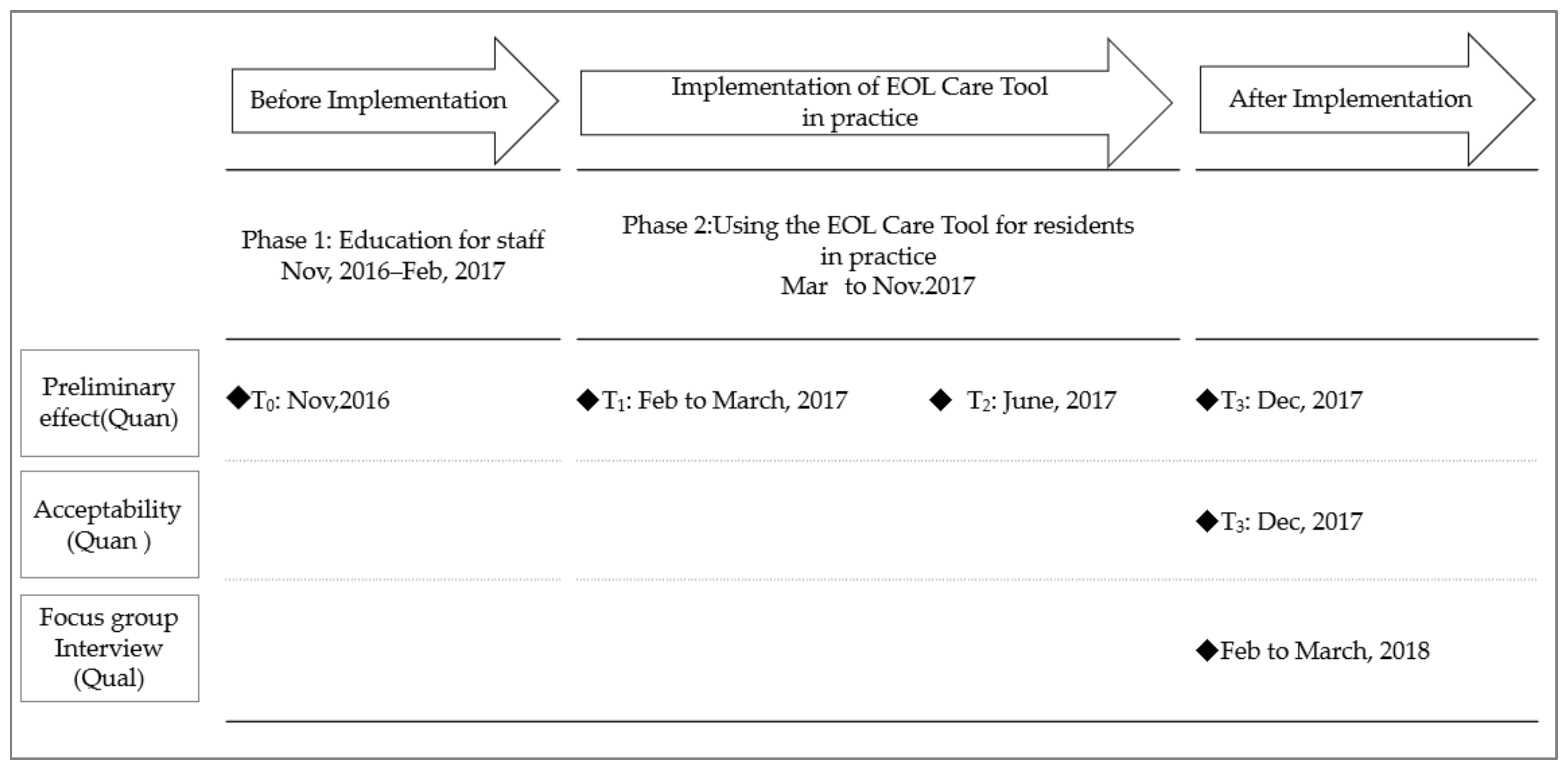

2.1. Design

2.2. Setting

- A low-support section (approximately 400 residents): Most residents here were living independently or with assistance. Nurses and care workers supported residents mainly in IADLs. Residents’ health was relatively stable.

- A high-support section (approximately 40 residents): Similar to a nursing home, many residents here were provided care mainly in ADLs, were bedridden, and/or were approaching death.

- A facility-attached clinic (approximately 20 residents): This accepts residents from the other two sections as outpatients or inpatients for medical treatment or advanced care. More residents were approaching death here than in the other two sections.

2.3. Participants

2.4. Intervention

2.4.1. Development of the Intervention

2.4.2. The EOL Care Tool Intervention

2.5. Data Collection

2.5.1. Characteristics of Participants

2.5.2. Quantitative Data

Preliminary Effect

Acceptability

2.5.3. Qualitative Data

2.6. Data Analysis

2.6.1. Quantitative Data

2.6.2. Qualitative Data

2.7. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Results

3.2. Characteristics

3.3. Preliminary Effect

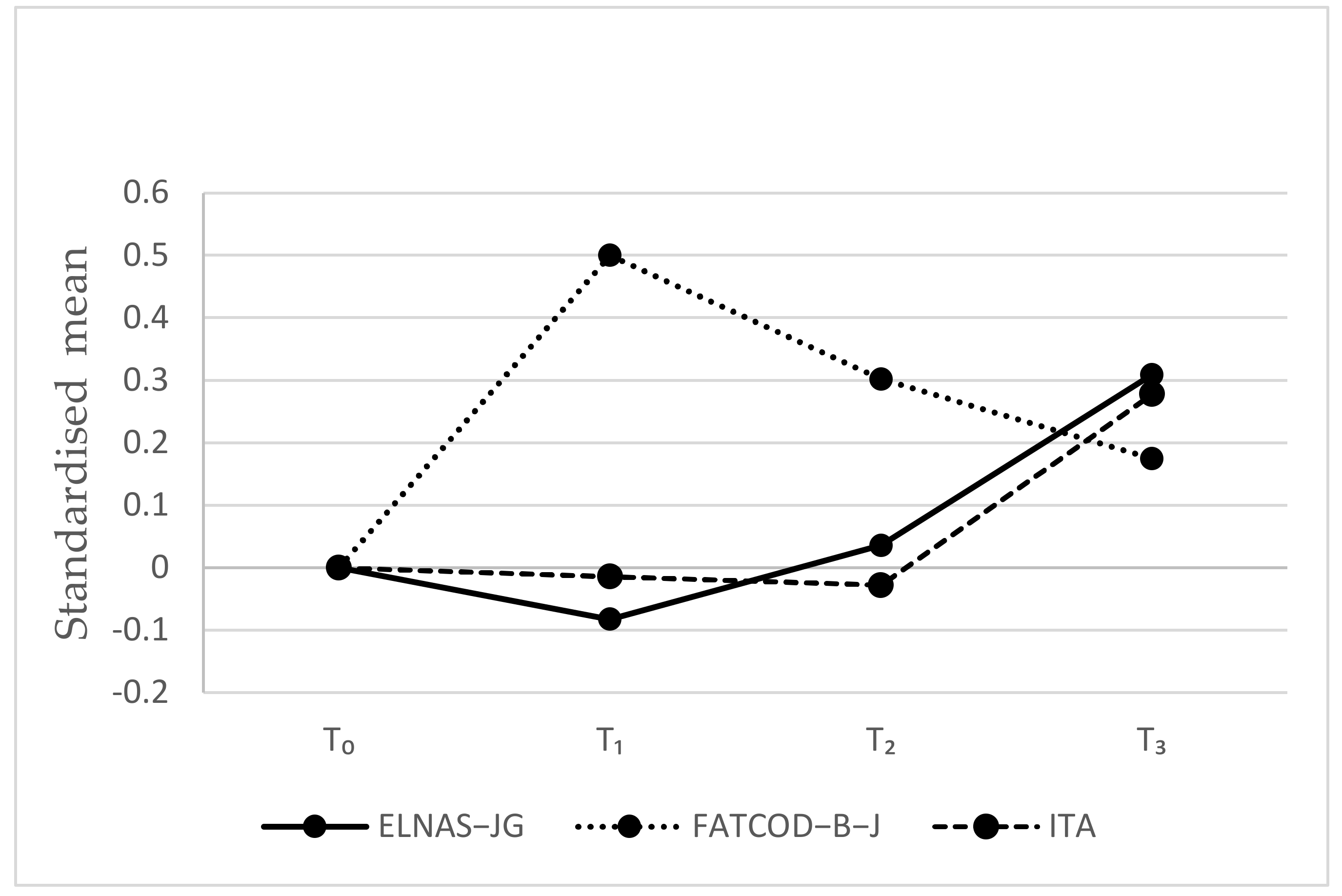

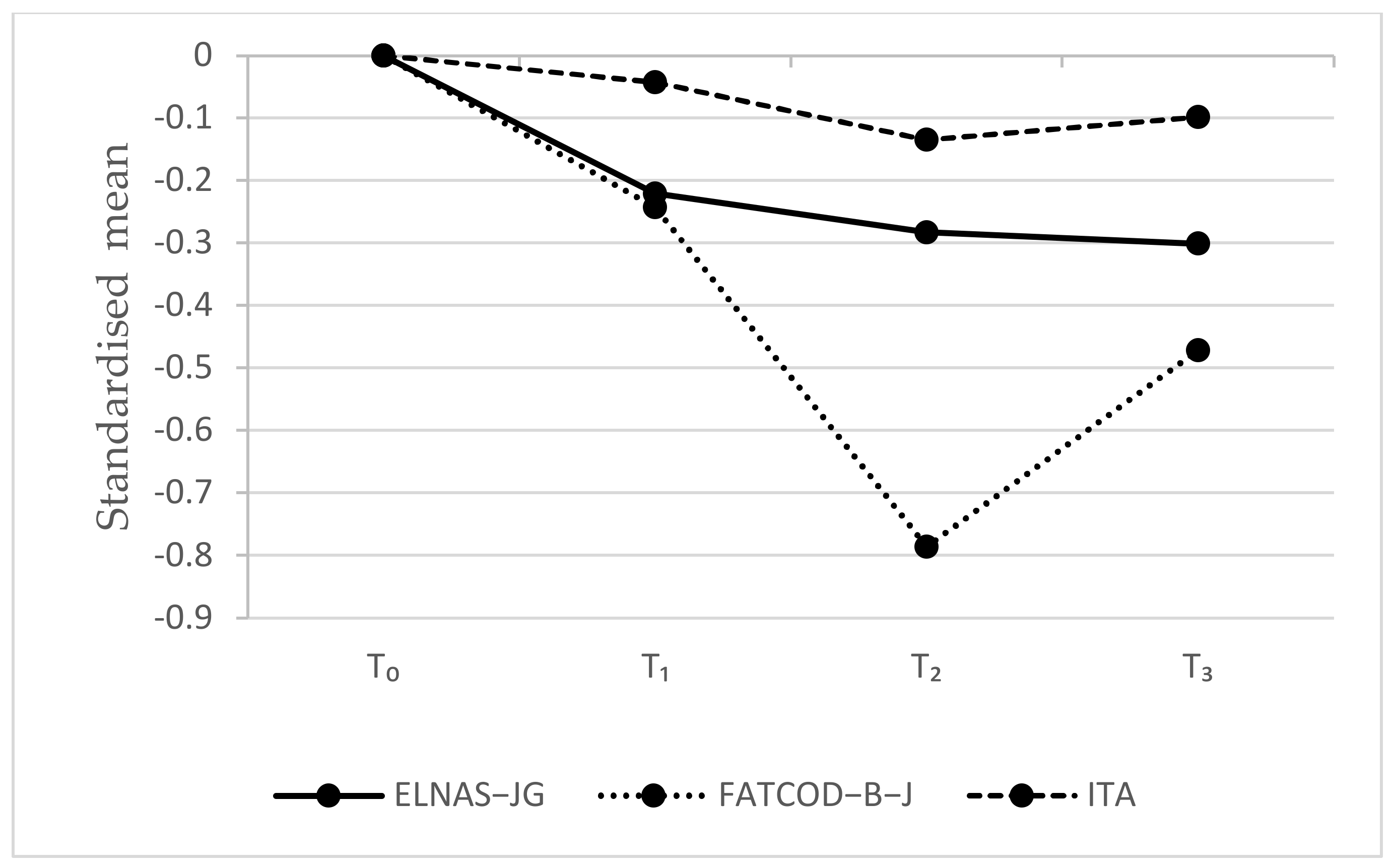

3.4. Acceptability

3.5. Qualitative Results

“We should provide care in consideration of what we can do for residents. I feel that such awareness among staff is probably increasing [by the tool].”(Nurse C, clinic)

“By looking at one resident’s [structured] document [including previous information from when the resident was more independent], I was able to know what the family had thought at that time.”(Nurse D, clinic)

“It is hard for care workers like me to ask [residents and families] such [sensitive] things (talking about end-of-life). I’m not in a managerial position; I just write [what I hear] on [the structured document].”(Care worker F, high-support section)

4. Discussion

4.1. Preliminary Effect

4.2. Acceptability

4.3. Implications for Further Research

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

UMIN Clinical Trial Registry

Appendix A

| Category | Subcategory | Interview Excerpts |

|---|---|---|

| Improvement in commitment to and practices for end-of-life care | Improving staff’s awareness of and commitment to end-of-life care | “I think [that the] awareness among staff [toward end-of-life care for residents] was less before. I think that as a resident approaches death, we should give him or her more comfort. Or we should provide care taking into consideration what we can do for the residents. I feel that such awareness among staff is probably increasing.” (Nurse C, clinic) |

| Improving staff’s daily-care practices (e.g., symptom management, supporting daily life, looking back at residents’ care goals) | “In the care [for residents] at the end of life, for example, when the rubber sheets [water-repellent sheets] were wrinkled…because the wrinkles might make them feel uncomfortable, I was careful [not to wrinkle the sheets]. In that way, I thought about caring for residents.” (Care worker G, high-support section) | |

| Improving staff’s end-of-life care practices (e.g., providing care that reflects the wishes and preferences of residents and their family members) | “I think we were able to do what we could until the end, in consideration of the things valued by residents and their families.” (Care worker C, high-support section) | |

| Learning end-of-life care and improving skills | “How to care for residents who are approaching death… I felt I had improved the level [of care]. I also believe I learned things.” (Care worker G, high-support section) | |

| Improvement in interdisciplinary collaboration | Consolidating information about residents’ and family members’ wishes, care, and conditions | “There were residents…who were approaching death when this [tool implementation] began. Now, everyone can see what kind of care we should provide for such residents. The staff can see the direction of care just by looking at the documents.” (Care worker E, high-support section) |

| Sharing information about residents’ and family members’ wishes, care, and conditions through documents and conferences | “By looking at a resident’s document [structured document including information from when the resident was more independent], I was able to know what the family had thought at that time. I was able to know what I had not previously known [about the family’s attitudes].” (Nurse D, clinic) | |

| Conducting frequent conferences where nurses and care workers can have discussions from the same perspective regarding residents’ care | “About sharing [information] between nurses and care workers…it’s great to be able to discuss things together while sharing documents.” (Care worker E, high-support section) | |

| Increasing communication among nurses and care workers in care practice | “When I couldn’t ask a resident for information but had to gather it…I developed relationships with staff from other sections, as well as families…and had conversations with them.” (Nurse G, clinic) | |

| Cooperating well within the section | “The negative side was that we couldn’t really share information [with another section]. [But] in the clinic, we can share [information].” (Nurse C, clinic) | |

| Unity between staff, residents, and their families with a common goal for better end-of-life care. | Increasing communication and closeness among staff, residents, and their families | “Staff can enhance their closeness with the residents. In that sense, I thought it [the EOL Care Tool] was good.” (Nurse G, clinic) |

| Having more personal conversations regarding end-of-life care with residents and their families | “I thought it was good for me to be able to talk deeply with residents’ families.” (Nurse F, high-support section) | |

| Uniting staff, residents, and their families for end-of-life care | “By having common goals, we were able to join forces to provide end-of-life care for residents using this [the structured document].” (Nurse E, clinic) | |

| Inspiring residents and their families to be interested in end-of-life care | Providing opportunities to discuss end-of-life care | “I think it [the tool] provided an opportunity for families to think [about end-of-life wishes and so on].” (Care worker J, low-support section) |

| Improving residents’ and families’ interest in residents’ end-of-life | “One family member said, ‘I think I have to talk things over with my brothers. Could you provide us with relevant materials if there [are any]?’” (Care worker J, low-support section) | |

| Preventing omission of end-of-life care for nurses and care workers. | Preventing oversight in care practice and symptom observation | “The checklist items help us to avoid missing anything.” (Nurse G, clinic) |

| Unifying care practices among staff | “What we have to do now is unification, I think. Perhaps [we will proceed] by doing what is written in the [structured] documents.” (Nurse B, clinic) | |

| Reluctance to address the work regarding end-of-life care | Belief that having conversations related to dying is not the job of care workers | “It is hard for care workers like me to ask [residents and families] such [sensitive] things (talking about end-of-life). I’m not in a managerial position; I just write [what I hear] on [the structured document].” (Care worker F, high-support section) |

| Resistance to end-of-life care conversations that might worsen relationships with residents and their families or create a psychological burden for them | “We called the resident’s family and asked about their hopes for the resident’s end-of-life. But I really didn’t want to do it at first. We already had a relationship [with the resident and his/her family], and the resident was well [in good health]. So, why do I have to talk with them about end-of-life? I thought [about] it. I felt very resistant [at that time].” (Care worker D, high-support section) | |

| Facing difficulties and lacking confidence in addressing medical matters regarding end-of-life care | “Care workers will also communicate [medical information to residents or families], but I think it is difficult [for care workers].” (Care worker E, high-support section) | |

| Barriers to talking about end-of-life care in ways other than face-to-face conversations with family members | “I thought it was painful and difficult for staff to talk to families about such serious topics over the phone.” (Care worker F, high-support section) | |

| Psychological burden of residents and their families toward end-of-life care communication | Residents and family members are resistant to end-of-life care communication | “The topic of life and death is a sensitive issue, isn’t it? Some residents who said they were well [in good health] wondered why they now had to talk about such things [end-of-life topics].” (Care worker M, low-support section) |

| Residents and family members sense a psychological burden related to end-of-life care communication | “When the staff talk about such things [end-of-life], the residents would have negative thoughts. One person asked, ‘Will I die soon?’” (Care worker F, high-support section) | |

| Increased workload | Increased workload owing to the documentation and conferences | “Documentation must be made easier. There are too many records to create.” (Nurse B, clinic) |

| Finding it troublesome to create extra records and/or organize conferences | “The number of conferences is gradually increasing. I found it a bit troublesome because we talk with residents and their families about the same topics repeatedly.” (Nurse C, clinic) |

References

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Population Prospects. 2019. Available online: https://population.un.org/wpp/Download/Standard/Population (accessed on 15 May 2020).

- Bone, A.E.; Gomes, B.; Etkind, S.N.; Verne, J.; Murtagh, F.; Evans, C.J.; Higginson, I.J. What is the impact of population ageing on the future provision of end-of-life care? Population-based projections of place of death. Palliat. Med. 2018, 32, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Community Comprehensive Care System. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/hukushi_kaigo/kaigo_koureisha/chiiki-houkatsu/ (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Welfare Statistics Handbook. 2018. Available online: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/youran/indexyk_1_2.html (accessed on 15 June 2021). (In Japanese)

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Survey on Attitudes toward Medical Care in the End Stages of Life. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/list/dl/saisyuiryo_a_h29.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2021).

- Hirakawa, Y.; Kuzuya, M.; Uemura, K. Opinion survey of nursing or caring staff at long-term care facilities about end-of-life care provision and staff education. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2009, 49, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. Research Project Report on the Current State of Medical Care in Nursing Homes for Older People. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/05-Shingikai-12601000-Seisakutoukatsukan-Sanjikanshitsu_Shakaihoshoutantou/0000158749.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2021).

- Latta, L.E.; Ross, J. Exploring the impact of palliative care education for care assistants employed in residential aged care facilities in Otago, New Zealand. Sites A J. Soc. Anthr. Cult. Stud. 2010, 7, 30–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nasu, K.; Konno, R.; Rn, H.F. End-of-life nursing care practice in long-term care settings for older adults: A qualitative systematic review. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2019, 26, 12771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hockley, J.; Watson, J.; Oxenham, D.; Murray, S. The integrated implementation of two end-of-life care tools in nursing care homes in the UK: An in-depth evaluation. Palliat. Med. 2010, 24, 828–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandervoort, A.; Block, L.V.D.; van der Steen, J.; Volicer, L.; Stichele, R.V.; Houttekier, D.; Deliens, L. Nursing Home Residents Dying With Dementia in Flanders, Belgium: A Nationwide Postmortem Study on Clinical Characteristics and Quality of Dying. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2013, 14, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, Y.; Sekiya, M. Licensing and Training Requirements for Direct Care Workers in Japan. J. Aging Soc. Policy 2003, 15, 113–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Overview of Care Service at Facilities and Offices Surveys. 2016. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/kaigo/service16/;20162016; (accessed on 15 May 2020). (In Japanese)

- Nomura Research Institute. Survey of Residences for Older People. 2017. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/06-Seisakujouhou-12300000-Roukenkyoku/71_nomura.pdf;2017 (accessed on 6 December 2020). (In Japanese)

- Schell, E.S.; Kayser-Jones, J. “Getting into the skin”: Empathy and role taking in certified nursing assistants’ care of dying residents. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2007, 20, 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, J.; Hockley, J.; Dewar, B. Barriers to implementing an integrated care pathway for the last days of life in nursing homes. Int. J. Palliat. Nurs. 2006, 12, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hockley, J.; Pace, O.B.O.; Froggatt, K.; Block, L.V.D.; Onwuteaka-Philipsen, B.; Kylänen, M.; Szczerbińska, K.; Gambassi, G.; Pautex, S.; Payne, S.A. A framework for cross-cultural development and implementation of complex interventions to improve palliative care in nursing homes: The PACE steps to success programme. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Di Giulio, P.; Finetti, S.; Giunco, F.; Basso, I.; Rosa, D.; Pettenati, F.; Bussotti, A.; Villani, D.; Gentile, S.; Boncinelli, L.; et al. The Impact of Nursing Homes Staff Education on End-of-Life Care in Residents with Advanced Dementia: A Quality Improvement Study. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2019, 57, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Froggatt, K.; Patel, S.; Algorta, G.P.; Bunn, F.; Burnside, G.; Coast, J.; Dunleavy, L.J.; Goodman, C.; Hardwick, B.; Kinley, J.; et al. Namaste Care in nursing care homes for people with advanced dementia: Protocol for a feasibility randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e026531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppitz, A.; Bosshard, G.; Blanc, G.; Hediger, H.; Payne, S.; Volken, T. Pain Intervention for people with Dementia in nursing homes (PID): Study protocol for a quasi-experimental nurse intervention. BMC Palliat. Care 2017, 16, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota-Romero, E.; Esteban-Burgos, A.A.; Puente-Fernández, D.; García-Caro, M.P.; Hueso-Montoro, C.; Herrero-Hahn, R.M.; Montoya-Juárez, R. NUrsing Homes End of Life care Program (NUHELP): Developing a complex intervention. BMC Palliat. Care 2021, 20, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, K.; Ersek, M.; Virani, R.; Malloy, P.; Ferrell, B. End-Of-Life Nursing Education Consortium Geriatric Training Program: Improving Palliative Care in Community Geriatric Care Settings. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 2008, 34, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hockley, J.; Dewar, B.; Watson, J. Promoting end-of-life care in nursing homes using an ‘integrated care pathway for the last days of life’. J. Res. Nurs. 2005, 10, 135–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reymond, L.; Israel, F.J.; Charles, M.A. A residential aged care end-of-life care pathway (RAC EoLCP) for Australian aged care facilities. Aust. Health Rev. 2011, 35, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smets, T.; PACE Trial Group; Onwuteaka-Philipsen, B.B.D.; Miranda, R.; Pivodic, L.; Tanghe, M.; van Hout, H.; Pasman, R.H.R.W.; Oosterveld-Vlug, M.; Piers, R.; et al. Integrating palliative care in long-term care facilities across Europe (PACE): Protocol of a cluster randomized controlled trial of the ‘PACE Steps to Success’ intervention in seven countries. BMC Palliat. Care 2018, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Verhofstede, R.; Smets, T.; Cohen, J.; Costantini, M.; Noortgate, N.V.D.; Deliens, L. Implementing the care programme for the last days of life in an acute geriatric hospital ward: A phase 2 mixed method study. BMC Palliat. Care 2016, 15, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ellershaw, J. Care of the dying patient: The last hours or days of life * Commentary: A “good death” is possible in the NHS. BMJ 2003, 326, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, J.; Marshall, B.; Sheward, K.; Allan, S. Staff perceptions of the impact of the Liverpool Care Pathway in aged residential care in New Zealand. Int. J. Palliat. Nurs. 2012, 18, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuberger, J.G.C.; Aaronovitch, D.; Bonser, T.; Charlesworth-Smith, D.; Cox, D.; Guthrie, C. More Care, Less Pathway: A Review of the Liverpool Care Pathway; Williams Lea: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ohr, S.; Jeong, S.; Saul, P. Cultural and religious beliefs and values, and their impact on preferences for end-of-life care among four ethnic groups of community-dwelling older persons. J. Clin. Nurs. 2017, 26, 1681–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Guidelines Regarding the Decision Process about Medical and Long-Term Care in End-of-Life Care in Japan. 2018. Available online: http://xn--mhlw-z63cqbymyj.go.jp/file/06-Seisakujouhou-10800000-Iseikyoku/0000197721.pdf (accessed on 27 April 2021).

- Kawakami, Y.; Hamano, J.; Kotani, M.; Kuwata, M.; Yamamoto, R.; Kizawa, Y.; Shima, Y. Recognition of End-of-life Care by Nursing Care Staff, and Factors Impacting Their Recognition: An Exploratory Research Using Mixed Methods. Palliat. Care Res. 2019, 14, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawara, H.; Fukahori, H.; Hirooka, K.; Miyashita, M. Quality Evaluation and Improvement for End-of-life Care toward Residents in Long Term Care Facilities in Japan: A Literature Review. Palliat. Care Res. 2016, 11, 401–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tsuruwaka, M.; Semba, Y. Study on confirmation of intention concerning end-of-life care upon moving into welfare facilities for elderly requiring care. Jpn. Assoc. Bioeth. 2010, 20, 158–164. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, D.J.; Kreuter, M.; Spring, B.; Cofta-Woerpel, L.; Linnan, L.; Weiner, D.; Bakken, S.; Kaplan, C.P.; Squiers, L.; Fabrizio, C.; et al. How We Design Feasibility Studies. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2009, 36, 452–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Farquhar, M.C.; Ewing, G.; Booth, S. Using mixed methods to develop and evaluate complex interventions in palliative care research. Palliat. Med. 2011, 25, 748–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, C.T. Nursing Research: Generating and Assessing Evidence for Nursing Practice; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Yamagata, C.; Hirooka, K.; Kanno, Y.; Taguchi, A.; Matsumoto, S.; Miyashita, M.; Fukahori, H. Intervention and Implementation Studies on Integrated Care Pathway for End-of-Life Care in Long-term Care Facilities: A Scoping Review. Palliat. Care Res. 2018, 13, 313–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, N.; Staal, J.; van Ravensberg, C.; Hobbelen, J.; Rikkert, M.O.; der Sanden, M.N.-V. Outcome instruments to measure frailty: A systematic review. Ageing Res. Rev. 2011, 10, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumura-Hiroshige, A.; Fukahori, H.; Yoshioka, S.; Kuwata, M.; Nishiyama, M.; Takamichi, K. Development of the End-of-Life Care Nursing Attitude Scale for Japanese Geriatrics. J. Hosp. Palliat. Nurs. 2018, 20, 272–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakai, Y.; Miyashita, M.; Sasahara, T.; Koyama, Y.; Shimizu, Y.; Kawa, M. Factor structure and reliability of the Japanese version of the Frommelt Attitudes Toward Care of the Dying Scale (FATCOD-B-J). Jpn. J. Cancer Nurs. 2006, 11, 723–729. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugimoto, T.; Kamei, T. Developing an Assessment Scale of Health Care Professionals’ Recognition of a Successful Interdisciplinary Team Approach in Health Care Facilities for the Elderly: Analysis of Reliability and Validity. J. Jpn. Acad. Nurs. Sci. 2011, 31, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Holm, S. A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scand. J. Stat. 1979, 6, 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Elo, S.; Kyngäs, H. The qualitative content analysis process. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 62, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallory, J.L. The impact of a palliative care educational component on attitudes toward care of the dying in undergraduate nursing students. J. Prof. Nurs. 2003, 19, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Okumura-Hiroshige, A.; Fukahori, H.; Yoshioka, S.; Nishiyama, M.; Takamichi, K.; Kuwata, M. Effect of an end-of-life gerontological nursing education programme on the attitudes and knowledge of clinical nurses: A non-randomised controlled trial. Int. J. Older People Nurs. 2020, 15, e12309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, M.; Braun, K. Nurses’ and care workers’ attitudes toward death and caring for dying older adults in Japan. Int. J. Palliat. Nurs. 2010, 16, 593–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horey, D.; Street, A.; Sands, A.F. Acceptability and feasibility of end-of-life care pathways in Australian residential aged care facilities. Med. J. Aust. 2012, 197, 106–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Block, L.V.D.; Honinx, E.; Pivodic, L.; Miranda, R.; Onwuteaka-Philipsen, B.D.; Van Hout, H.; Pasman, H.R.W.; Oosterveld-Vlug, M.; Koppel, M.T.; Piers, R.; et al. Evaluation of a Palliative Care Program for Nursing Homes in 7 Countries. JAMA Intern. Med. 2020, 180, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izumi, S.; Nagae, H.; Sakurai, C.; Imamura, E. Defining end-of-life care from perspectives of nursing ethics. Nurs. Ethic 2012, 19, 608–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unroe, K.T.; Cagle, J.G.; Lane, K.A.; Callahan, C.M.; Miller, S.C. Nursing Home Staff Palliative Care Knowledge and Practices: Results of a Large Survey of Frontline Workers. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2015, 50, 622–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fryer, S.; Bellamy, G.; Morgan, T.; Gott, M. “Sometimes I’ve gone home feeling that my voice hasn’t been heard”: A focus group study exploring the views and experiences of health care assistants when caring for dying residents. BMC Palliat. Care 2016, 15, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Beernaert, K.; Smets, T.; Cohen, J.; Verhofstede, R.; Costantini, M.; Eecloo, K.; Noortgate, N.V.D.; Deliens, L. Improving comfort around dying in elderly people: A cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2017, 390, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Components | Implementation | |

|---|---|---|

| The lectures comprised the following six modules: (Each lecture lasted approximately 60 min.) “What is end-of-life care?” “Cultural and ethical issues” “Communication and loss, grief, and bereavement” “Pain management” “Symptom management” “Care in dying phase and death” “How to use structured documents?” | Lectures for staff were conducted as follows: Researchers provided lectures for staff. Each module was conducted several times, in face-to-face lectures and, DVD-recorded lectures, to facilitate the participation of all staff (nurses and care workers). |

| The document consists of four types of sheets: “Assessment sheet” (initial, ongoing) These two documents aimed to confirm and share the thoughts and wishes of residents and their families about their life and end-of-life between staff. The documents included the following information:

“Conference sheets” (1, 2) These documents were used to assess the residents’ physical/psychological condition and care process, and to discuss care for expected condition changes. They contained the following information to assess changes/decline in residents’ physical/psychological conditions: weight, activity, walking, depression, food intake, etc., based on existing literature on frailty. These sheets comprised three sections: discussion of physical and mental health assessment, information shared with family members, and physician’s judgment (if any). Shared information was important to promote shared decision-making with family members and to avoid conflict among staff and family members due to recognition gaps. “Daily records” This document aimed to standardize the assessment and care provided by nurses and care workers. It contained items for symptom management and a list of required care practices during the dying phase. Required care practices included daily support, information on treatment, and caring for family. This document was a sheet typically used for residents who were judged as being close to death in the regular conference. “Preparation sheet for imminent death” This document aimed to ensure that the required activities and rituals during the period of dying and after death are performed properly. It contained items such as procedures at dying and death and bereavement care. | The structured document was implemented as follows: Staff (nurses and care workers) started using structured documents for residents’ care. Both nurses and care workers used the structured documents, in parallel with existing records. Staff talked with residents and their families about the resident’s end-of-life care and recorded the information in the structured documents before the regular conference. |

| Regular conferences were conducted by nurses, care workers, and sometimes clerks in the long-term-care facility. In the conferences, discussions were to be conducted regarding the management of changes in residents’ wishes/anxieties and decline/recovery in their physical/psychological condition. The condition of their frailty or dying trajectory and the prospects of their health condition were to be discussed. | Implementation of the regular conferences was as follows: Staff conducted regular conferences for end-of-life care of residents, using the assessment sheet and conference sheet. The interval of discussion was decided by staff according to residents’ physical condition, in consultation with nurse/care worker managers and doctors: one week, one month, three months, or six months (considering the typical workflow in Japanese long-term care facilities). Usually, the interval was adjusted reversibly and shortened with resident deterioration, but it could also be extended if their condition improved. |

| To set up a support system for the implementation of the EOL Care Tool, researchers provided the managers of nurses and care workers an educator role and asked them to adjust the conference schedule and support the staff with clinical implementation. Educators supported staff using a manual created to implement the intervention (the manual included explanations of how to use this tool). Their roles included advising on how to gather and assess residents’ information using this tool, facilitating communication about end-of-life with staff and residents/their families, encouraging staff through face-to-face conversation and regular conferences, and helping the staff cope with anxiety. | Implementation of educational support was as follows: The nurse managers and care worker managers, as educators, supported the staff in clinical cases and in the use of structured documents through direct guidance and discussions in conferences and practice. |

| Nurses (n = 14) | Care Workers (n = 33) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Gender | Female | 14 (100.0) | 28 (84.8) |

| Male | 0 (0.0) | 5 (15.1) | |

| Age (years) | ≤29 | 0 (0.0) | 9 (27.3) |

| 30–39 | 1 (7.1) | 3 (9.1) | |

| 40–49 | 4 (28.6) | 12 (36.4) | |

| 50–59 | 8 (57.1) | 8 (24.2) | |

| ≥60 | 1 (7.1) | 1 (3.0) | |

| Occupation (multiple answers allowed) | RN | 13 | 0 |

| LPN | 1 | 0 | |

| Certified care worker | 0 | 27 | |

| Social worker | 0 | 2 | |

| Licensed home-helper | 0 | 9 | |

| Care manager | 0 | 4 | |

| Other | 0 | 1 | |

| Educational level | High school | 0 (0.0) | 6 (18.1) |

| Vocational school | 12 (85.7) | 11 (33.3) | |

| Junior college | 1 (7.1) | 7 (21.2) | |

| University | 1 (7.1) | 9 (27.3) | |

| Years of experience in their profession | ≤5 | 0 (0.0) | 10 (30.3) |

| 6–10 | 0 (0.0) | 11 (33.3) | |

| 11–15 | 3 (21.4) | 6 (18.2) | |

| ≥16 | 11 (78.5) | 6 (18.2) | |

| Years working in the current workplace | ≤5 | 8 (57.1) | 21 (63.6) |

| 6–10 | 4 (28.6) | 6 (18.1) | |

| 11–15 | 0 (0.0) | 4 (12.1) | |

| ≥16 | 2 (14.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 2 (6.1) | |

| Measure | T0 | T1 | T2 | T3 | Adjusted p-Value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | T0-T1 | T0-T2 | T0-T3 | |

| Nurses (n = 14) | |||||||||||

| ELNAS-JG | 14 | 82.4 (19.4) | 13 | 80.8 (17.0) | 14 | 83.1 (20.4) | 14 | 88.4 (20.5) | 0.99 | 0.74 | 0.02 * |

| FATCOD-B-J | 13 | 115.5 (12.6) | 12 | 121.8 (13.9) | 13 | 119.3 (14.0) | 14 | 117.7 (14.6) | 0.09 | 0.21 | 0.11 |

| ITA | 12 | 56.0 (14.4) | 13 | 55.8 (12.3) | 12 | 55.6 (13.9) | 14 | 60.0 (13.4) | 0.99 | 0.93 | 0.02 * |

| Care workers (n = 33) | |||||||||||

| ELNAS-JG | 33 | 77.2 (11.3) | 30 | 74.7 (11.4) | 28 | 74.0 (15.0) | 33 | 73.8 (15.2) | 0.25 | 0.22 | 0.27 |

| FATCOD-B-J | 31 | 114.5 (7.0) | 29 | 112.8 (7.6) | 29 | 109.0 (8.7) | 31 | 111.2 (9.2) | 0.11 | 0.00 ** | 0.07 |

| ITA | 31 | 58.8 (16.3) | 31 | 58.1 (15.1) | 30 | 56.6 (15.0) | 33 | 57.2 (14.9) | 0.73 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| Nurse (n = 14) | Care Worker (n = 33) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | |||||||

| Strongly Agree | Agree | Disagree | Strongly Disagree | Strongly Agree | Agree | Disagree | Strongly Disagree | |

| The frequency of symptom assessment for residents who are dying has increased since the introduction of the EOL Care Tool. | 7 (50.0) | 7 (50.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 11 (33.3) | 14 (42.4) | 8 (24.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| The EOL Care Tool has helped me understand appropriate care for residents who are dying. | 5 (35.7) | 8 (57.1) | 1 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (15.2) | 21 (63.6) | 6 (18.2) | 1 (3.0) |

| The overall care for those who are dying has improved since the implementation of the EOL Care Tool. | 2 (14.3) | 11 (78.6) | 1 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (15.2) | 16 (48.5) | 11 (33.3) | 1 (3.0) |

| The EOL Care Tool document is easy to use for staff. | 1 (7.1) | 5 (35.7) | 7 (50.0) | 1 (7.1) | 1 (3.0) | 12 (36.4) | 17 (51.5) | 3 (9.1) |

| Category | Subcategory | Nurse (n = 9) | Care Worker (n = 13) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Improvement in commitment to and practices for end-of-life care | Improving staff’s awareness of and commitment to end-of-life care | 77% | 46% |

| Improving staff’s daily-care practices (e.g., symptom management, supporting daily life, looking back at residents’ care goals) | 33% | 38% | |

| Improving staff’s end-of-life care practices (e.g., providing care that reflects the wishes and preferences of residents and their family members) | 66% | 76% | |

| Learning end-of-life care and improving skills | 22% | 38% | |

| Improvement in interdisciplinary collaboration | Consolidating information about residents’ and family members’ wishes, care, and conditions | 44% | 53% |

| Sharing information about residents’ and family members’ wishes, care, and conditions through documents and conferences | 55% | 46% | |

| Conducting frequent conferences where nurses and care workers can have discussions from the same perspective regarding residents’ care | 44% | 30% | |

| Increasing communication among nurses and care workers in care practice | 33% | 7% | |

| Cooperating well within the section | 44% | 23% | |

| Unity between staff, residents, and their families with a common goal for better end-of-life care | Increasing communication and closeness among staff, residents, and their families | 55% | 23% |

| Having more personal conversations regarding end-of-life care with residents and their families | 22% | 7% | |

| Uniting staff, residents, and their families for end-of-life care | 55% | 7% | |

| Inspiring residents and their families to be interested in end-of-life care | Providing opportunities to discuss end-of-life care | 11% | 46% |

| Improving residents’ and families’ interest in residents’ end-of-life | 11% | 23% | |

| Preventing omission of end-of-life care for nurses and care workers | Preventing oversights in care practice and symptom observation | 33% | 7% |

| Unifying care practices among staff | 22% | 7% | |

| Reluctance to address the work regarding end-of-life care | Belief that having conversations related to dying is not the job of care workers | 0% | 15% |

| Resistance to end-of-life care conversations that might worsen relationships with residents and their families or create a psychological burden for them | 11% | 46% | |

| Facing difficulties and lacking confidence in addressing medical matters regarding end-of-life care | 11% | 38% | |

| Barriers to talking about end-of-life care in ways other than face-to-face conversations with family members | 22% | 38% | |

| Psychological burden of residents and their families toward end-of-life care communication | Residents and family members are resistant to end-of-life care communication | 0% | 53% |

| Residents and family members sense a psychological burden related to end-of-life care communication | 11% | 15% | |

| Increased workload | Increased workload owing to the documentation and conferences | 22% | 15% |

| Finding it troublesome to create extra records and/or organize conferences | 33% | 23% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yamagata, C.; Matsumoto, S.; Miyashita, M.; Kanno, Y.; Taguchi, A.; Sato, K.; Fukahori, H. Preliminary Effect and Acceptability of an Intervention to Improve End-of-Life Care in Long-Term-Care Facilities: A Feasibility Study. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1194. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9091194

Yamagata C, Matsumoto S, Miyashita M, Kanno Y, Taguchi A, Sato K, Fukahori H. Preliminary Effect and Acceptability of an Intervention to Improve End-of-Life Care in Long-Term-Care Facilities: A Feasibility Study. Healthcare. 2021; 9(9):1194. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9091194

Chicago/Turabian StyleYamagata, Chihiro, Sachiko Matsumoto, Mitsunori Miyashita, Yusuke Kanno, Atsuko Taguchi, Kana Sato, and Hiroki Fukahori. 2021. "Preliminary Effect and Acceptability of an Intervention to Improve End-of-Life Care in Long-Term-Care Facilities: A Feasibility Study" Healthcare 9, no. 9: 1194. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9091194

APA StyleYamagata, C., Matsumoto, S., Miyashita, M., Kanno, Y., Taguchi, A., Sato, K., & Fukahori, H. (2021). Preliminary Effect and Acceptability of an Intervention to Improve End-of-Life Care in Long-Term-Care Facilities: A Feasibility Study. Healthcare, 9(9), 1194. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9091194