Overcoming Obstacles to Develop High-Performance Teams Involving Physician in Health Care Organizations

Abstract

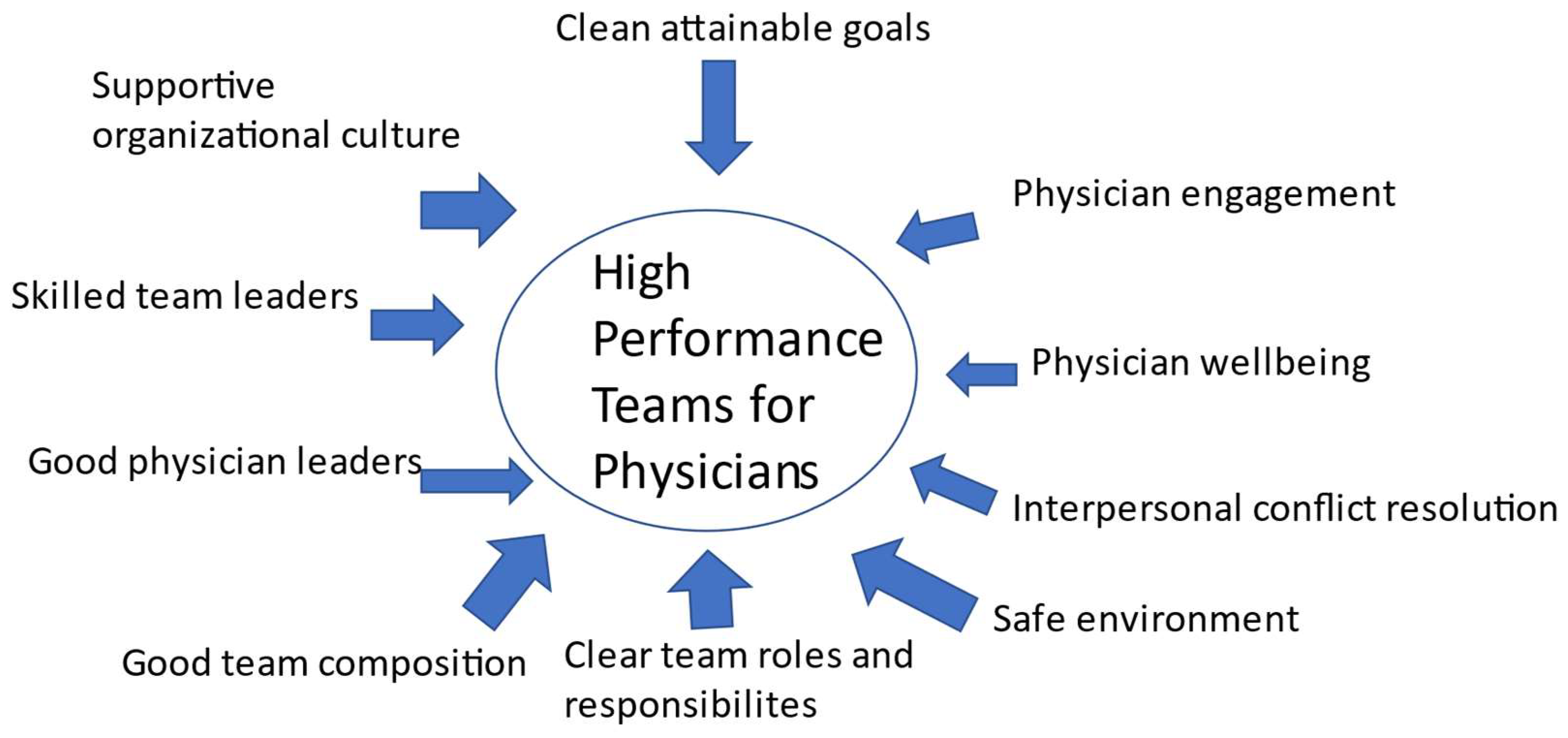

:1. Introduction

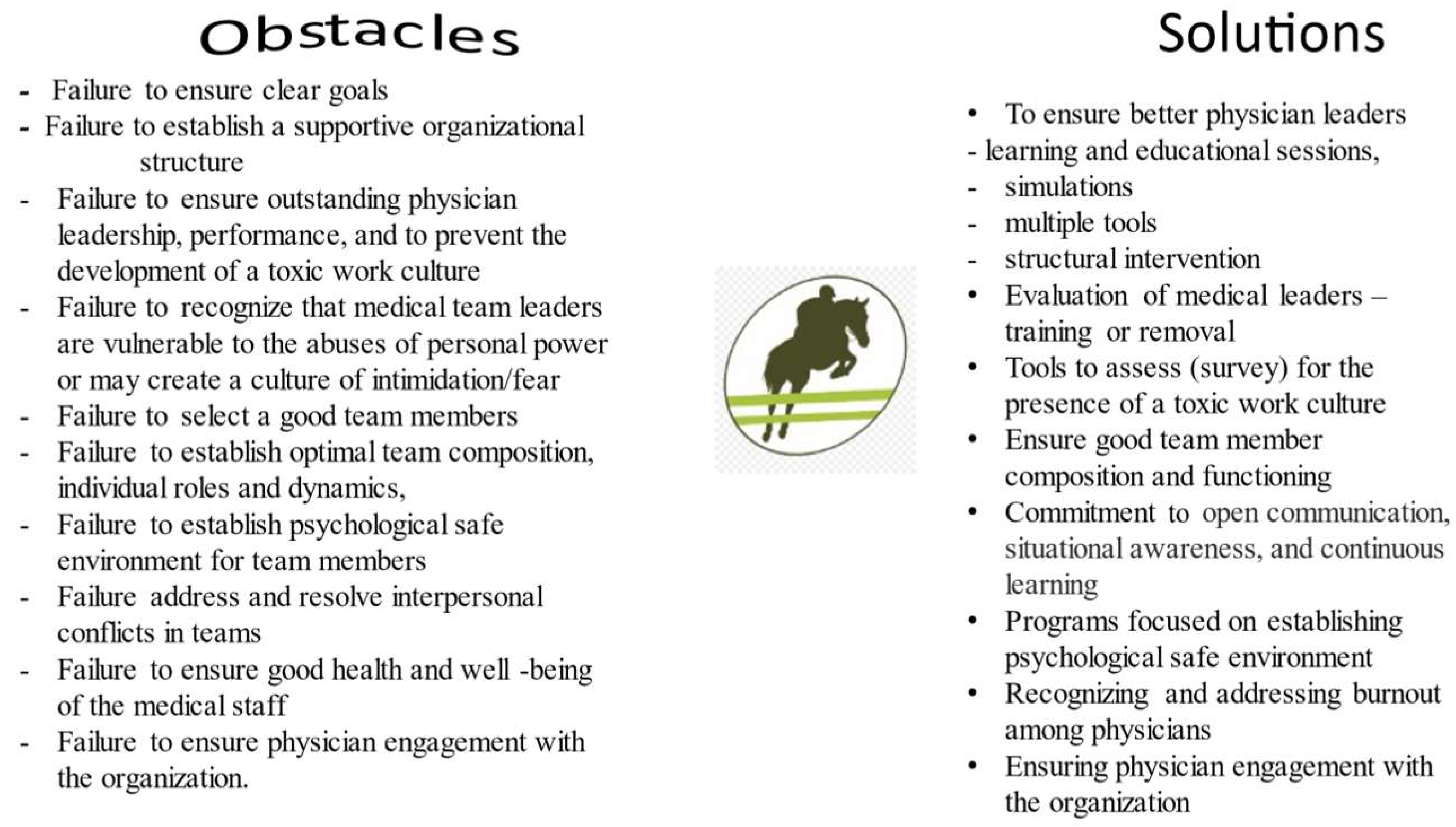

2. Obstacles to Develop High-Performance Teams Involving Physicians

2.1. Failure to Ensure That the Goals, Purpose, Mission, and Vision Are Clearly Defined

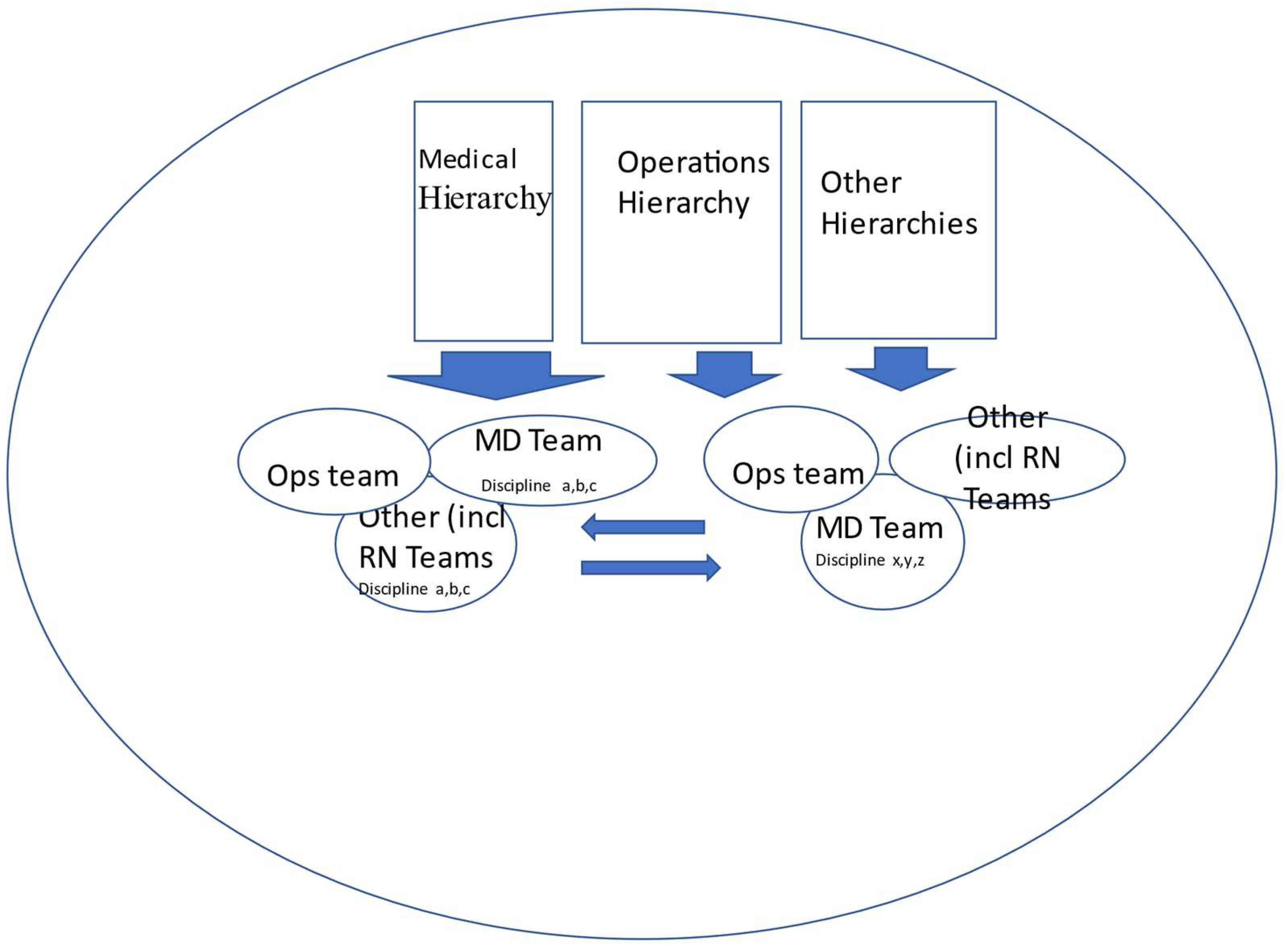

2.2. Failure to Establish a Supportive Organizational Structure That Encourages High-Performance Teams

2.3. Failure to Ensure Outstanding Physician Leadership

2.4. Failure to Recognize That Team Leaders Are Vulnerable to the Abuses of Personal Power or May Create a Culture of Intimidation/Fear with the Development of a Toxic Work Culture

2.5. Failure to Select a Good Team and Team Members—Team Members Who Like to Work in Teams or Are Willing and Able to Learn How to Work in a Team and Ensure a Well-Balanced Team Composition

2.6. Failure to Establish Optimal Team Composition, Individual Roles and Dynamics, and Clear Roles for Members of the Team

2.7. Failure to Establish Psychological Safe Environment for Team Members

2.8. Failure to Address and Resolve Interpersonal Conflicts in Teams

2.9. Failure to Ensure Good Health and Well-Being of Physician Staff

2.10. Failure to Ensure Physician Engagement with the Organization

3. Overcoming Obstacles to Develop High-Performance Teams—Solutions

3.1. Overcoming the Failure to Ensure That the Goals, Purpose, Mission, and Vision Are Clearly Defined

3.2. Overcoming the Failure to Establish a Supportive Organizational Structure That Encourages High-Performance Teams

3.3. Overcoming the Failure to Ensure Outstanding Physician Leadership

3.4. Overcoming the Failure to Recognize That Team Leaders Are Vulnerable to the Abuses of Personal Power or May Create a Culture of Intimidation/Fear, and a Toxic Work Culture

3.5. Overcoming the Failure to Select a Good Team and Team Members—Team Members Who Like to Work in Teams or Are Willing and Able to Learn How to Work in a Team and Ensure a Well-Balanced Team Composition

3.6. Overcoming the Failure to Establish Optimal Team Composition, Individual Roles and Dynamics, and Clear Roles for Members of the Team

3.7. Overcoming the Failure to Establish Psychological Safe Environment for Team Members

3.8. Overcoming the Failure to Address and Resolve Interpersonal Conflicts in Teams

3.9. Overcoming the Failure to Ensure Good Health and Well-Being of Physician Staff

3.10. Overcoming the Failure to Ensure Physician Engagement with the Organization

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Heinemann, G. Teams in Health Care Settings. In Team Performance in Health Care. Assessment and Development; Heinman, G., Zeiss, A., Eds.; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Colenso, M. High Performing Teams; Butterworth & Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Kyle, M.; Aveling, E.-L.; Singer, S.-J. Establishing High-Performing Teams: Lessons From Health Care. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2020, 61, 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- Thiagarajan, P.; McKimm, J. Mapping transactional analysis to clinical leadership models. Br. J. Hosp. Med. Lond 2019, 80, 600–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leggat, S.G.; Bartram, T.; Stanton, P. High performance work systems: The gap between policy and practice in health care reform. J. Health Organ. Manag. 2011, 25, 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Majmudar, A.; Jain, A.K.; Chaudry, J.; Schwartz, R.W. High-Performance Teams and the Physician Leader: An Overview. J. Surg. Educ. 2010, 67, 205–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Committee on Development of High Performance Teamwork; American College of Surgeons. Statement on high-performance teams. Bull. Am. Coll. Surg. 2010, 95, 23–24. [Google Scholar]

- Edmondson, A.; Higgins, M.; Singer, S.; WeineR, J. Understanding Psychological Safety in Health Care and Education Organizations: A Comparative Perspective. Res. Hum. Dev. 2016, 13, 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicotte, C.; Champagne, F.; Contandriopoulos, A.P.; Barnsley, J.; Beland, F.; Leggat, S.G.; Denis, J.L.; Bilodeau, H.; Langley, A.; Bremond, M.; et al. A conceptual framework for the analysis of health care organizations’ performance. Health Serv. Manag. Res. 1998, 11, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katzenbach, J.; Smith, D. The Wisdom of Teams: Creating the High Performance Organization; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Losada, M. The Complex Dynamics of High Performance Teams. Math. Comput. Model. 1999, 30, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunham, N.C.; Kindig, D.A.; Schulz, R. The value of the physician executive role to organizational effectiveness and performance. Health Care Manag. Rev. 1994, 19, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, R.W.; Pogge, C. Physician leadership: Essential skills in a changing environment. Am. J. Surg. 2000, 180, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mickan, S.; Rodger, S. Characteristics of effective teams:a literature review. Aust. Health Rev. 2000, 23, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- The Center for Organizational Design Developing High Performance Teams. What They Are and How to Make Them Work. Available online: http://www.centerod.com/developing-high-performance-teams/ (accessed on 10 June 2021).

- Heineman, G.; Zeiss, A. A model of team performance. In Team Performance in Health Care. Assessment and Development; Springer Science: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ogbeiiwi, O. General concepts of goals and goal-setting in healthcare: A narrative review. J. Manag. Organ. 2018, 27, 324–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McDonald, A.; Sarfraz, A. Failing hospitals: Mission statements to drive service improvement? Leadersh. Health Serv. 2015, 28, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmidt, S.; Prinzie, A. The organization’s mission statement: Give up hope or resuscitate? A search for evidence-based recommendations. Adv. Health Care Manag. 2011, 10, 25–41. [Google Scholar]

- Peltier, J.W.; Kleimenhagen, A.K.; Naidu, G.M. Integrating multiple publics into the strategic plan. The best plans can be derailed without comprehensive up-front research. J. Health Care Mark. 1996, 16, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Silva, A.; Araújo, B.; Serrão, D. The mission, vision and values in hospital management. J. Hosp. Adm. 2015, 5, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mickan, S.; Rodger, S. The organisational context for teamwork: Comparing health care and business literature. Aust. Health Rev. 2000, 23, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Leggat, S.G.; Balding, C. Bridging existing governance gaps: Five evidence-based actions that boards can take to pursue high quality care. Aust. Health Rev. 2019, 43, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perreira, T.A.; Perrier, L.; Prokopy, M. Hospital Physician Engagement: A Scoping Review. Med. Care 2018, 56, 969–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leggat, S. Effective healthcare teams require effective team members: Defining teamwork competencies. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2007, 7, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leggat, S.G.; Balding, C. Achieving organisational competence for clinical leadership: The role of high performance work systems. J. Health Organ. Manag. 2013, 27, 312–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, T.; Fowler-Davis, S.; Nancarrow, S.; Ariss, S.M.B.; Enderby, P. Leadership in interprofessional health and social care teams: A literature review. Leadersh. Health Serv. Bradf. Engl. 2018, 31, 452–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Caldwell, D.F.; Chatman, J.; O’Reilly, C.A., 3rd; Ormiston, M.; Lapiz, M. Implementing strategic change in a health care system: The importance of leadership and change readiness. Health Care Manag. Rev. 2008, 33, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodall, A. Physician-Leaders and Hospital Performance: Is There an Association? Soc. Sci. Med. 2011, 73, 535–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tasi, M.C.; Keswani, A.; Bozic, K.J. Does physician leadership affect hospital quality, operational efficiency, and financial performance? Health Care Manag. Rev. 2019, 44, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoller, J.; Goodal, A.; Baker, A. Why the Best Hospitals Are Managed by Doctors. Available online: https://hbr.org/2016/12/why-the-best-hospitals-are-managed-by-doctors (accessed on 30 August 2021).

- Berghout, M.; Fabbricotti, I.; Buljac-Samardžić, M.; Hilders, C. Medical leaders or masters?-A systematic review of medical leadership in hospital settings. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0184522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Clay-Williams, R.; Ludlow, K.; Testa, L.; Li, Z.; Braithwaite, J. Medical leadership, a systematic narrative review: Do hospitals and healthcare organisations perform better when led by doctors? BMJ Open 2017, 7, e014474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Egger, C.; Kimatian, S. Lessons Learned: From a C-130 to the C-Suite in Health Care. Int. Anesth. Clin. 2019, 57, 144–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vainieri, M.; Ferre, F.; Giacomelli, G.; Nuti, S. Explaining performance in health care: How and when top management competencies make the difference. Health Care Manag. Rev. 2019, 44, 306–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, M.; Lopez, J.; Messman, A.; Xu, K.T.; McLaughlin, T.; Richman, P. Emergency Medicine Resident Perception of Abuse by Consultants: Results of a National Survey. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2020, 76, 814–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Wei, L.; Mao, J.; Jia, H.; Li, P.; Li, Y.; Fu, Y.; Zhao, S.; Liu, H.; Jiang, K.; et al. Extent and risk factors of psychological violence towards physicians and Standardised Residency Training physicians: A Northern China experience. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2020, 18, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubairi, A.J.; Ali, M.; Sheikh, S.; Ahmad, T. Workplace violence against doctors involved in clinical care at a tertiary care hospital in Pakistan. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2019, 69, 1355–1359. [Google Scholar]

- Llewellyn, A.; Karageorge, A.; Nash, L.; Li, W.; Neuen, D. Bullying and sexual harassment of junior doctors in New South Wales, Australia: Rate and reporting outcomes. Aust. Health Rev. 2019, 43, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosta, J.; Aasland, O.G. Perceived bullying among Norwegian doctors in 1993, 2004 and 2014–2015: A study based on cross-sectional and repeated surveys. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e018161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Clements, J.M.; King, M.; Nicholas, R.; Burdall, O.; Elsey, E.; Bucknall, V.; Awopetu, A.; Mohan, H.; Humm, G.; Nally, D.M.; et al. Bullying and undermining behaviours in surgery: A qualitative study of surgical trainee experiences in the United Kingdom (UK) & Republic of Ireland (ROI). Int. J. Surg. 2020, 84, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ogunsemi, O.O.; Alebiosu, O.C.; Shorunmu, O.T. A survey of perceived stress, intimidation, harassment and well-being of resident doctors in a Nigerian Teaching Hospital. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2010, 13, 183–186. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shabazz, T.; Parry-Smith, W.; Oates, S.; Henderson, S.; Mountfield, J. Consultants as victims of bullying and undermining: A survey of Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists consultant experiences. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e011462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hu, Y.; Ellis, R.; Hewitt, D.; Yang, A.; Cheung, E.; Moskowitz, J.; Potts, J.; Buyske, J.; Hoyt, D.; Nasca, T.; et al. Discrimination, Abuse, Harassment, and Burnout in Surgical Residency Training. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 1741–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, L. Culture of bullying in medicine starts at the top. CMAJ 2018, 190, E1459–E1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pei, K.Y.; Cochran, A. Workplace Bullying Among Surgeons-the Perfect Crime. Ann. Surg. 2019, 269, 43–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, R.F.; Buljac-Samardzic, M.; Akdemir, N.; Hilders, C.; Scheele, F. What do we really assess with organisational culture tools in healthcare? An interpretive systematic umbrella review of tools in healthcare. BMJ Open Qual. 2020, 9, e000826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez, L.; Bernet, P. Diversity improves performance and outcomes. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2019, 111, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Triandis, H.C. Cross-Cultural Industrial and Organizational Psychology. In Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology; Triandis, H., Dunnette, M., Hough, L., Eds.; Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1994; pp. 103–172. [Google Scholar]

- van Knippenberg, D.; Schippers, M.C. Work group diversity. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2007, 58, 515–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shaikh, U.; Acosta, D.A.; Freischlag, J.A.; Young, H.M.; Villablanca, A.C. Developing Diverse Leaders at Academic Health Centers: A Prerequisite to Quality Health Care? Am. J. Med. Qual. 2018, 33, 440–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dotson, E.; Nuru-Jeter, A. Setting the Stage for a Business Case for Leadership Diversity in Healthcare: History, Research, and Leverage. J. Healthc. Manag. 2012, 57, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gill, G.K.; McNally, M.J.; Berman, V. Effective Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Practices. In Healthcare Management Forum; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2018; Volume 31, pp. 196–199. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Prieto, P.; Bellard, E.; Schneider, S.C. Experiencing diversity, conflict, and emotions in teams. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 52, 413–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.; Boyle, B. A theoretical model of transformational leadership’s role in diverse teams. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2009, 30, 455–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, R.; Kozlowski, S.W.; Shapiro, M.; Salas, E. Toward a Definition of Teamwork in Emergency Medicine. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2008, 15, 1104–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crozier, M.S.; Ting, H.Y.; Boone, D.C.; O’Regan, N.B.; Bandrauk, N.; Furey, A.; Hogan, M.P. Use of human patient simulation and validation of the team situation awareness global assessment technique (TSAGAT): A multidisciplinary team assessment tool in trauma education. J. Surg. Educ. 2015, 72, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, B. Physician and nurse practitioner: Conflict and reward. Ann. Intern. Med. 1975, 82, 702–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mark, A. Developing the doctor manager: Reflecting on the personal costs. Health Serv. Manag. Res. 1995, 8, 252–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargeant, J.; Loney, E.; Murphy, G. Effective interprofessional teams: “contact is not enough” to build a team. J. Contin. Educ. Health Prof. 2008, 28, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kravitz, D.; Martin, B. Ringelmann rediscovered: The original article. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 50, 936–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midwinter, M.J.; Mercer, S.; Lambert, A.W.; de Rond, M. Making difficult decisions in major military trauma: A crew resource management perspective. BMJ Mil. Health 2011, 157, S299–S304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, M.A.; Borrill, C.S.; Dawson, J.F.; Brodbeck, F.; Shapiro, D.A.; Haward, B. Leadership clarity and team innovation in health care. Leadersh. Q. 2003, 14, 393–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendrick, M.; Kendrick, K.; Morton, P.; Taylor, N.F.; Leggat, S.G. Hospital Staff Report It Is Not Burnout, but a Normal Stress Reaction to an Uncongenial Work Environment: Findings from a Qualitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doctors of BC Policy Statement Promoting Psychological Safety for Physicians. Available online: https://www.doctorsofbc.ca/sites/default/files/2017-06-promotingpsychologicalsafetyforphysicians_id_113100.pdf (accessed on 3 October 2020).

- Swensen, S.; Gorringe, G.; Caviness, J.; Peters, D. Leadership by design: Intentional organization development of physician leaders. J. Manag. Dev. 2016, 35, 549–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, H.W. Dysfunctional health service conflict: Causes and accelerants. Health Care Manag. Frederick 2012, 31, 178–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carelton, J.; Craig, G. Initial Briefing on the Results of the NRGH Cultural Assessment. Available online: Shawglobalnews.files.wordpress.com (accessed on 28 January 2020).

- Dewa, C.S.; Loong, D.; Bonato, S.; Trojanowski, L. The relationship between physician burnout and quality of healthcare in terms of safety and acceptability: A systematic review. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e015141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotenstein, L.S.; Torre, M.; Ramos, M.A.; Rosales, R.C.; Guille, C.; Sen, S.; Mata, D.A. Prevalence of Burnout Among Physicians: A Systematic Review. JAMA 2018, 320, 1131–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- West, C.P.; Dyrbye, L.N.; Shanafelt, T.D. Physician burnout: Contributors, consequences and solutions. J. Intern. Med. 2018, 283, 516–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- LeNoble, C.A.; Pegram, R.; Shuffler, M.L.; Fuqua, T.; Wiper, D.W., 3rd. To Address Burnout in Oncology, We Must Look to Teams: Reflections on an Organizational Science Approach. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2020, 16, e377–e383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, M.; Willard-Grace, R.; Knox, M.; Larson, S.A.; Magill, M.K.; Grumbach, K.; Peterson, L.E. Team Configurations, Efficiency, and Family Physician Burnout. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2020, 33, 368–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, B.; Ahmad, F.; Stewart, D.E. Physician health, stress and gender at a university hospital. J. Psychosom. Res. 2003, 54, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markos, S.; Sridevi, M. Employee Engagement: The Key to Improving Performance. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2010, 5, 89–96. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, M.; Chumney, F.; Wright, C.; Buckingham, M. Global Study of Engagement The Technical Repor. Available online: https://www.adp.com/-/media/adp/ResourceHub/pdf/ADPRI/ADPRI0102_2018_Engagement_Study_Technical_Report_ (accessed on 30 August 2021).

- Spurgeon, P.; Mazelan, P.M.; Barwell, F. Medical engagement: A crucial underpinning to organizational performance. Health Serv. Manag. Res. 2011, 24, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, K.; Eggers, J.; Keller, S.; McDonald, A. The imperative of culture: A quantitative analysis of the impact of culture on workforce engagement, patient experience, physician engagement, value-based purchasing, and turnover. J. Healthc. Leadersh. 2017, 9, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- The King’s Fund Leadership and Engagement for Improvement in the NHS. Available online: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/leadership-engagement (accessed on 8 August 2019).

- Kaissi, A. Enhancing physician engagement: An international perspective. Int. J. Health Serv. 2014, 44, 567–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taitz, J.M.; Lee, T.H.; Sequist, T.D. A framework for engaging physicians in quality and safety. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2012, 21, 722–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabkin, S.W.; Dahl, M.; Patterson, R.; Mallek, N.; Straatman, L.; Pinfold, A.; Charles, M.K.; van Gaal, S.; Wong, S.; Vaghadia, H. Physician engagement: The Vancouver Medical Staff Association engagement charter. Clin. Med. 2019, 19, 278–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shanafelt, T.D.; Dyrbye, L.N.; Sinsky, C.; Hasan, O.; Satele, D.; Sloan, J.; West, C.P. Relationship Between Clerical Burden and Characteristics of the Electronic Environment With Physician Burnout and Professional Satisfaction. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2016, 91, 836–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perreira, T.A.; Perrier, L.; Prokopy, M.; Neves-Mera, L.; Persaud, D.D. Physician engagement: A concept analysis. J. Healthc. Leadersh. 2019, 11, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hockey, P.M.; Bates, D.W. Physicians’ identification of factors associated with quality in high- and low-performing hospitals. Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Patient Saf. 2010, 36, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grol, R.; Mokkink, H.; Smits, A.; Van Eijk, J.; Beek, M.; Mesker, P.; Mesker-Niesten, J. Work satisfaction of general practitioners and the quality of patient care. Fam. Pract. 1985, 2, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begun, J.; Zimmerman, B.; Dooley, K. Health Care Organizations as Complex Adaptive Systems. In Advances in Health Care Organization Theory; Mick, S., Wyttenbach, M., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2003; pp. 253–288. [Google Scholar]

- Buljac-Samardzic, M.; Doekhie, K.D.; van Wijngaarden, J.D.H. Interventions to improve team effectiveness within health care: A systematic review of the past decade. Hum. Resour. Health 2020, 18, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aggarwal, R.; Mytton, O.T.; Derbrew, M.; Hananel, D.; Heydenburg, M.; Issenberg, B.; MacAulay, C.; Mancini, M.E.; Morimoto, T.; Soper, N.; et al. Training and simulation for patient safety. Qual. Saf. Health Care 2010, 19 (Suppl. 2), i34–i43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rothkrug, A.; Mahboobi, S.K. Simulation Training and Skill Assessment in Anesthesiology; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard, M.; Graham, S.; Bonacum, D. The human factor: The critical importance of effective teamwork and communication in providing safe care. Qual. Saf. Health Care 2004, 13 (Suppl. 1), i85–i90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Agency for Health Care Research and Quality The CUSP Method. Available online: https://www.ahrq.gov/hai/cusp/index.html (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- Baker, D.; Gustafson, S.; Beaubien, J.; Salas, E.; Bara, P. Medical Team Training Programs in Health Care. Adv. Patient Saf. 2005, 4, 253–267. [Google Scholar]

- Leggat, S.G.; Dwyer, J. Improving hospital performance: Culture change is not the answer. Healthc. Q. 2005, 8, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoller, J. Developing physician leaders: Does it work? BMJ Lead. 2020, 4, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Council of Academic Hospitals of Ontario 360-Degree Physician Performance Review Toolkit. Available online: http://caho-hospitals.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/CAHO-360-Degree-Physician-PerformToolkit2009.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2020).

- Salas, E.; DiazGranados, D.; Klein, C.; Burke, C.S.; Stagl, K.C.; Goodwin, G.F.; Halpin, S.M. Does team training improve team performance? A meta-analysis. Hum. Factors 2008, 50, 903–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sax, H.C. Building high-performance teams in the operating room. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2012, 92, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.T.; Sexton, J.B.; Milne, J.; Frush, D.P. Practice and quality improvement: Successful implementation of TeamSTEPPS tools into an academic interventional ultrasound practice. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2015, 204, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, P.R.M. The use of concept maps for knowledge management: From classrooms to research labs. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2012, 402, 1979–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keats, J.P. Leadership and Teamwork: Essential Roles in Patient Safety. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 46, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehim, S.A.; DeMoor, S.; Olmsted, R.; Dent, D.L.; Parker-Raley, J. Tools for Assessment of Communication Skills of Hospital Action Teams: A Systematic Review. J. Surg. Educ. 2017, 74, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thylefors, I.; Persson, O.; Hellstrom, D. Team types, perceived efficiency and team climate in Swedish cross-professional teamwork. J. Interprof. Care 2005, 19, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, C.P.; Dyrbye, L.N.; Erwin, P.J.; Shanafelt, T.D. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2016, 388, 2272–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linzer, M.; Poplau, S.; Grossman, E.; Varkey, A.; Yale, S.; Williams, E.; Hicks, L.; Brown, R.L.; Wallock, J.; Kohnhorst, D.; et al. A Cluster Randomized Trial of Interventions to Improve Work Conditions and Clinician Burnout in Primary Care: Results from the Healthy Work Place (HWP) Study. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2015, 30, 1105–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sequeira, L.; Almilaji, K.; Strudwick, G.; Jankowicz, D.; Tajirian, T. EHR “SWAT” teams: A physician engagement initiative to improve Electronic Health Record (EHR) experiences and mitigate possible causes of EHR-related burnout. JAMIA Open 2021, 4, ooab018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeChant, P.F.; Acs, A.; Rhee, K.B.; Boulanger, T.S.; Snowdon, J.L.; Tutty, M.A.; Sinsky, C.A.; Thomas Craig, K.J. Effect of Organization-Directed Workplace Interventions on Physician Burnout: A Systematic Review. Mayo Clin. Proc. Innov. Qual. Outcomes 2019, 3, 384–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sexton, J.B.; Adair, K.C. Forty-five good things: A prospective pilot study of the Three Good Things well-being intervention in the USA for healthcare worker emotional exhaustion, depression, work-life balance and happiness. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e022695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kummerow, E.; Kirby, N. Organisational Culture; World Scientific Pub Co Inc.: Singapore, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- International Association for Public Participation IAP2 Spectrum. Available online: https://iap2canada.ca/Resources/Documents/0702-Foundations-Spectrum-MW-rev2%20(1).pdf (accessed on 30 August 2021).

- van de Riet, M.C.P.; Berghout, M.A.; Buljac-Samardzic, M.; van Exel, J.; Hilders, C.G.J.M. What makes an ideal hospital-based medical leader? Three views of healthcare professionals and managers: A case study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0218095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rabkin, S.W.; Frein, M. Overcoming Obstacles to Develop High-Performance Teams Involving Physician in Health Care Organizations. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1136. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9091136

Rabkin SW, Frein M. Overcoming Obstacles to Develop High-Performance Teams Involving Physician in Health Care Organizations. Healthcare. 2021; 9(9):1136. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9091136

Chicago/Turabian StyleRabkin, Simon W., and Mark Frein. 2021. "Overcoming Obstacles to Develop High-Performance Teams Involving Physician in Health Care Organizations" Healthcare 9, no. 9: 1136. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9091136

APA StyleRabkin, S. W., & Frein, M. (2021). Overcoming Obstacles to Develop High-Performance Teams Involving Physician in Health Care Organizations. Healthcare, 9(9), 1136. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9091136