Why Do Patients Leave against Medical Advice? Reasons, Consequences, Prevention, and Interventions

Abstract

1. Introduction

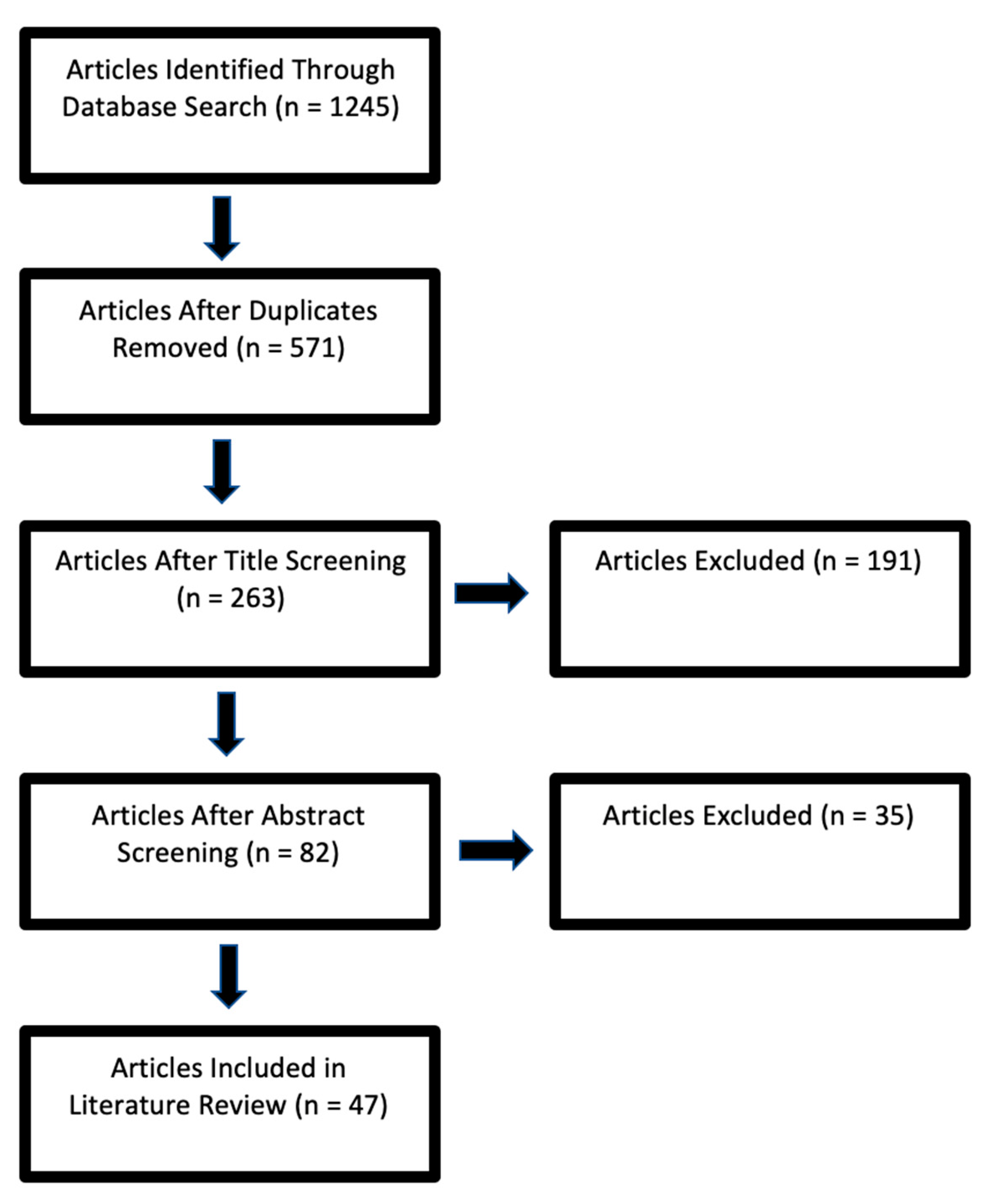

2. Materials and Methods

3. Discussion

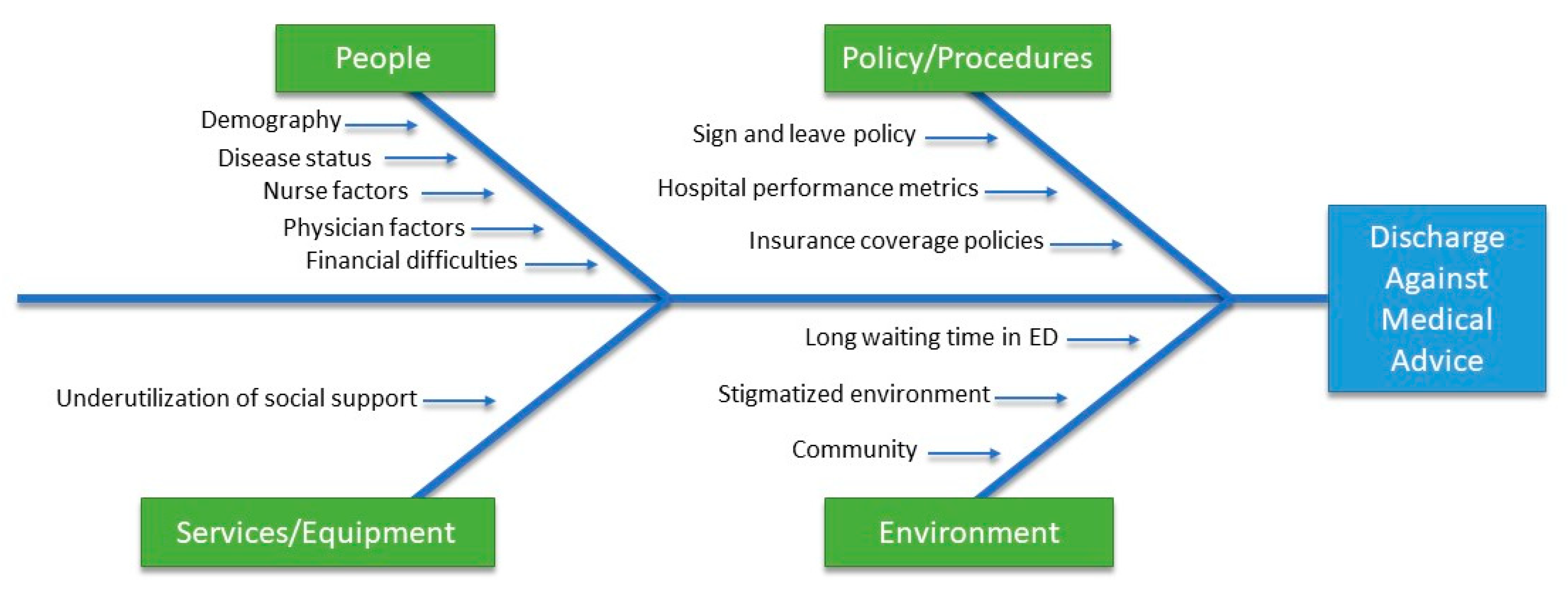

3.1. Reasons

3.1.1. People Factors

Physicians’ Factors

3.1.2. Nurses’ Factors

3.1.3. Demographic Characteristics

3.1.4. Associated Diseases

3.1.5. Financial Burden

3.2. Services/Equipment Factors

Underutilization of Social Support

3.3. Policy/Procedures Factors

3.3.1. Sign-Leave Policy

3.3.2. Hospital Performance Metric

Insurance Coverage Policies

3.4. Environmental Factors

3.4.1. Emergency Department Waiting

3.4.2. Community

3.5. Consequences of Leaving AMA

3.5.1. Readmission

3.5.2. Length of Stay

3.5.3. Cost of Readmission

3.5.4. Increased Mortality

3.6. Prevention Strategies for AMA

3.6.1. At the Provider Level

3.6.2. At the Hospital Level

3.6.3. At the Policymaker Level

3.6.4. Suggested Interventions to Ameliorate AMA

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alfandre, D.J. “I’m going home”: Discharges against medical advice. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2009, 84, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spooner, K.K.; Salemi, J.L.; Salihu, H.M.; Zoorob, R. Discharge against Medical Advice in the United States, 2002–2011. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2017, 92, 525–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfandre, D.; Brenner, J.; Onukwugha, E. Against medical advice discharges. J. Hosp. Med. 2017, 12, 836–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, S.W.; Li, J.; Gupta, R.; Chien, V.; Martin, R.E. What happens to patients who leave hospital against medical advice? Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2003, 168, 417–420. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, M.; Kim, H.; Qian, H.P.A. Readmission rates of patients discharged against medical advice: A matched cohort study. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e24459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harel, Z.; Silver, S.A.; McQuillan, R.F.; Weizman, A.V.; Thomas, A.; Chertow, G.M.; Nesrallah, G.; Chan, C.T.; Bell, C.M. How to Diagnose Solutions to a Quality of Care Problem. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2016, 11, 901–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Health Quality Ontario. Quality Improvement Guide; Queen’s Printer for Ontario: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2012.

- Pfuntner, A.; Wier, L.M.; Stocks, C. Most Frequent Conditions in U.S. Hospitals, 2011; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sayed, M.E.L.; Jabbour, E.; Maatouk, A.; Bachir, R.; Dagher, G.A. Discharge Against Medical Advice from the Emergency Department. Medicine 2016, 95, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noohi, K.; Komsari, S.; Nakhaee, N.; Feyzabadi, V.Y. Reasons for discharge against medical advice: A case study of emergency departments in Iran. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2013, 1, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohseni, M.; Alikhani, M.; Tourani, S.; Azami-Aghdash, S.; Royani, S.; Moradi-Joo, M. Rate and causes of discharge against medical advice in Iranian hospitals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Iran. J. Public Health 2015, 44, 902–912. [Google Scholar]

- Ti, L.; Ti, L. Leaving the hospital against medical advice among people who use illicit drugs: A systematic review. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, e53–e59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manouchehri, J.; Goodarzynejad, H.; Khoshgoftar, Z.; Fathollahi, M.S.; Abyaneh, M.A. Discharge against medical advice among inpatients with heart disease in Iran. J. Tehran Univ. Heart Cent. 2012, 7, 72–77. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, G.; Gautam, N.; Gautam, P.L.; Mahajan, R.K.; Ragavaiah, S. Patients Leaving Against Medical Advice—A National Survey. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 23, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, S.A.; Kwoh, C.K.; Krishnan, E. Factors Associated With Patients Who Leave Acute-Care Hospitals against Medical Advice. Am. J. Public Health 2007, 97, 2204–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labbé, E.; Herbert, D.; Haynes, J. Physicians’ attitude and practices in sickle cell disease pain management. J. Palliat. Care 2005, 21, 246–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.P.; Haywood Jr, C.; Beach, M.C.; Guidera, M.; Lanzkron, S.; Valenzuela-Araujo, D.; Rothman, R.E.; Dugas, A.F. Improving Emergency Providers’ Attitudes Toward Sickle Cell Patients in Pain. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2016, 51, 628–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, B.S.; Benjamin, L.J.; Payne, R.; Heidrich, G. Sickle cell-related pain: Perceptions of medical practitioners. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 1997, 14, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, J.; Feinglass, J.; Artz, N.; Hafner, J.; Tanabe, P. Sickle cell disease patients’ perceptions of emergency department pain management. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2012, 104, 449–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartley, M.K. Against medical advice. J. Trauma Nurs. 2014, 21, 314–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, J.; Joslin, J.; Goulette, A.; Grant, W.D.; Wojcik, S.M. Against Medical Advice: A Survey of ED Clinicians’ Rationale for Use. J. Emerg. Nurs. 2016, 42, 408–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliyu, Z.Y. Discharge against medical advice: Sociodemographic, clinical and financial perspectives. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 1997, 56, 325–327. [Google Scholar]

- Anis, A.H.; Sun, H.; Guh, D.P.; Schechter, M.T.; Shaughnessy, M.V.O. From the British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2002, 167, 633–637. [Google Scholar]

- Alfandre, D. Reconsidering against medical advice discharges: Embracing patient-centeredness to promote high-quality care and a renewed research agenda. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2013, 28, 1657–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeremiah, J.; O’Sullivan, P.S.M. Who leaves against medical advice? J. Gen. Intern. Med. 1995, 10, 403–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brook, M.; Hilty, D.M.; Liu, W.; Hu, R.; Frye, M.A. Discharge against medical advice from inpatient psychiatric treatment: A literature review. Psychiatr. Serv. 2006, 57, 1192–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, T.P.; Hartman, C.; Gifford, A.L.; Backus, L.I.; Morgan, R.O. Predictors of retention in HIV care among a national cohort of U.S. veterans. HIV Clin. Trials 2009, 10, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mugavero, M.J. Improving engagement in HIV care: What can we do? Top. HIV Med. Publ. Int. AIDS Soc. USA 2008, 16, 156. [Google Scholar]

- Torian, L.V.; Wiewel, E.W. Continuity of HIV-related medical care, New York City, 2005–2009: Do patients who initiate care stay in care? AIDS Patient Care STDS 2011, 25, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southern, W.N.; Nahvi, S.A.J. Increased risk of mortality and readmission among patients discharged against medical advice. Am. J. Med. 2012, 125, 594–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptist, A.P.; Warrier, I.; Arora, R.; Ager, J.; Massanari, R.M. Hospitalized patients with asthma who leave against medical advice: Characteristics, reasons, and outcomes. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2007, 119, 924–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, O.; Samad, M.A.; Khan, H.; Sarfraz, M.; Noordin, S.; Ahmad, T.; Nowshad, G. Leaving Against Medical Advice From In-patients Departments Rate, Reasons and Predicting Risk Factors for Re-visiting Hospital Retrospective Cohort From a Tertiary Care Hospital. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2019, 8, 474–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephen, W.; Hwang, M.D.M. Discharge against Medical Advice [Internet]. Patient Safety Network. 2005. Available online: https://psnet.ahrq.gov/web-mm/discharge-against-medical-advice#references (accessed on 28 November 2020).

- Opioid Abuse. Available online: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/287790-overview (accessed on 28 November 2020).

- Lee, C.A.; Cho, J.P.; Choi, S.C.; Kim, H.H.; Park, J.O. Patients who leave the emergency department against medical advice. Clin. Exp. Emerg. Med. 2016, 3, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weingart, S.N.; Davis, R.B.; Phillips, R.S. Patients discharged against medical advice from a general medicine service. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 1998, 13, 568–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lekas, H.M.; Alfandre, D.; Gordon, P.; Harwood, K.; Yin, M.T. The role of patient-provider interactions using an accounts framework to explain hospital discharges against medical advice. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 156, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yong, T.Y.; Fok, J.S.; Hakendorf, P.; Ben-Tovim, D.; Thompson, C.H.L.J. Characteristics and outcomes of discharges against medical advice among hospitalized patients. Intern. Med. J. 2013, 43, 798–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palepu, A.; Sun, H.; Kuyper, L.; Schechter, M.T.; Shaughnessy, M.V.O.; Anis, A.H. Predictors of early hospital readmission in HIV-infected patients with pneumonia. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2003, 18, 242–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devitt, P.J.; Devitt, A.C.; Dewan, M. An examination of whether discharging patients against medical advice protects physicians from malpractice charges. Psychiatr. Serv. 2000, 51, 899–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Mula, J.; González-Trujillo, A.; Simonet-Bennassar, M. Emergency and Mental Health Nurses’ Perceptions and Attitudes towards Alcoholics. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, V.H.J. Inpatient staff perceptions in providing care to individuals with co-occurring mental health problems and illicit substance use. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2010, 17, 862–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, R.; Snow, R.; Wakeman, S. Understanding why patients with substance use disorders leave the hospital against medical advice: A qualitative study. Subst. Abus. 2020, 41, 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Y.-F.; Tsai, M.-C.; Lin, Y.-P.; Weng, C.-E.; Chou, Y.-L.; Chen, C.-Y. An Alcohol Training Program Improves Chinese Nurses’ Knowledge, Self-Efficacy, and Practice: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2011, 35, 976–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerace, L.M.; Hughes, T.L.; Spunt, J. Improving nurses’ responses toward substance-misusing patients: A clinical evaluation project. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 1995, 9, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzyk, A.; Mullan, P.; Andolsek, K.M.; Derouin, A.; Smothers, Z.P.; Sanders, C.; Holmer, S. An Interprofessional Substance Use Disorder Course to Improve Students’ Educational Outcomes and Patients’ Treatment Decisions. Acad. Med. 2019, 94, 1792–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, F.; Mareiniss, D.P.; Iacovelli, C. The Importance of a Proper Against-Medical-Advice (AMA) Discharge: How Signing Out AMA May Create Significant Liability Protection for Providers. J. Emerg. Med. 2012, 43, 516–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jerrard, D.A.; Chasm, R.M. Patients Leaving Against Medical Advice [AMA] from the Emergency Department-Disease Prevalence and Willingness to Return. J. Emerg. Med. 2011, 41, 412–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beauchamp, T.L.; Childress, J.F. Principles of Biomedical Ethics; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Sayah, A.; Rogers, L.; Devarajan, K.; Kingsley-Rocker, L.; Lobon, L.F. Minimizing ED Waiting Times and Improving Patient Flow and Experience of Care. Emerg. Med. Int. 2014, 2014, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edmunds, M.; Sloan, F.A.; Steinwald, A.B. Geographic Adjustment in Medicare Payment: Phase II: Implications for Access, Quality, and Efficiency; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Haines, K.; Freeman, J.; Vastaas, C.; Rust, C.; Cox, C.; Kasotakis, G.; Fuller, M.; Krishnamoorthy, V.; Siciliano, M.; Alger, A.; et al. “I’m Leaving”: Factors That Impact Against Medical Advice Disposition Post-Trauma. J. Emerg. Med. 2020, 58, 691–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Albayati, A.; Douedi, S.; Alshami, A.; Hossain, M.A.; Sen, S.; Buccellato, V.; Cutroneo, A.; Beelitz, J.; Asif, A. Why Do Patients Leave against Medical Advice? Reasons, Consequences, Prevention, and Interventions. Healthcare 2021, 9, 111. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9020111

Albayati A, Douedi S, Alshami A, Hossain MA, Sen S, Buccellato V, Cutroneo A, Beelitz J, Asif A. Why Do Patients Leave against Medical Advice? Reasons, Consequences, Prevention, and Interventions. Healthcare. 2021; 9(2):111. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9020111

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlbayati, Asseel, Steven Douedi, Abbas Alshami, Mohammad A. Hossain, Shuvendu Sen, Vito Buccellato, Anamarrie Cutroneo, Jason Beelitz, and Arif Asif. 2021. "Why Do Patients Leave against Medical Advice? Reasons, Consequences, Prevention, and Interventions" Healthcare 9, no. 2: 111. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9020111

APA StyleAlbayati, A., Douedi, S., Alshami, A., Hossain, M. A., Sen, S., Buccellato, V., Cutroneo, A., Beelitz, J., & Asif, A. (2021). Why Do Patients Leave against Medical Advice? Reasons, Consequences, Prevention, and Interventions. Healthcare, 9(2), 111. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9020111