The Experiences of People with Dementia and Informal Carers Related to the Closure of Social and Medical Services in Poland during the COVID-19 Pandemic—A Qualitative Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Recruitment Process

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Demographics

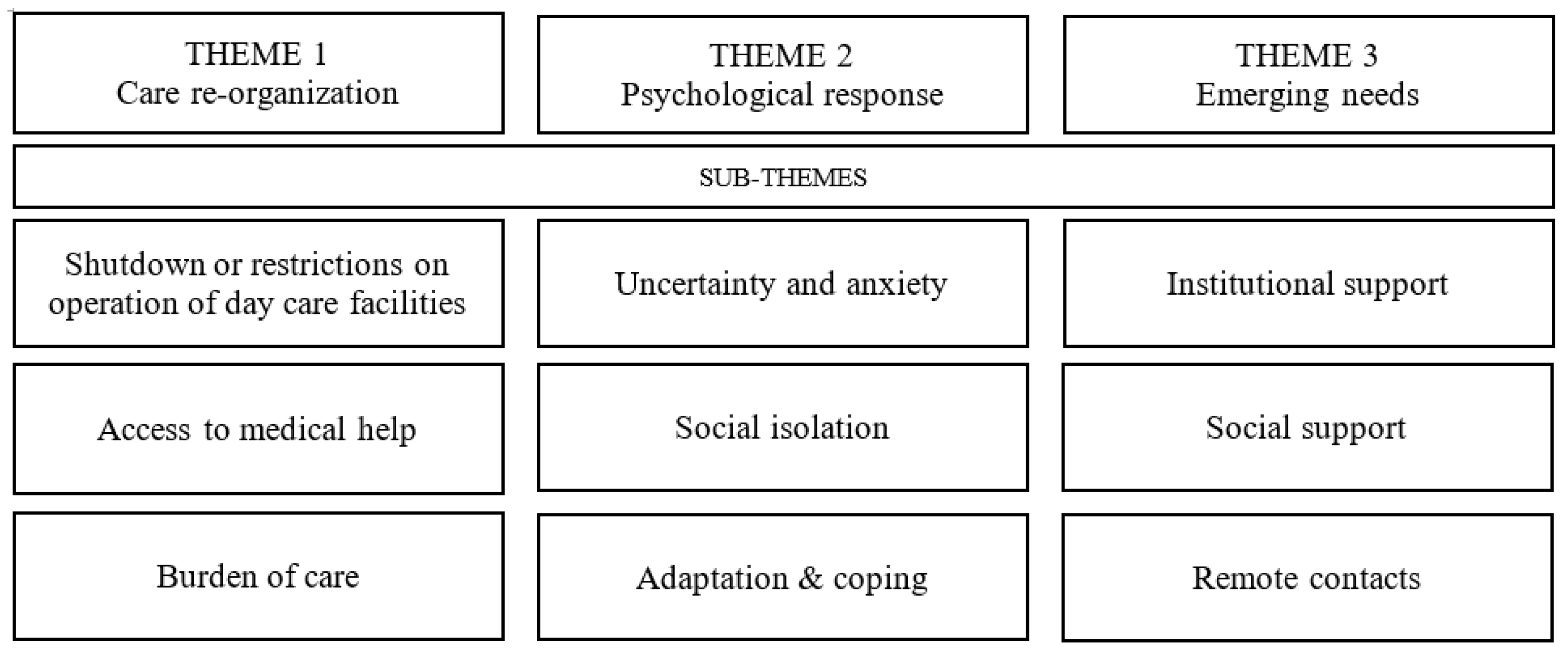

3.2. Qualitative Themes

3.3. Theme 1: Care Re-Organization

3.3.1. Shutdown or Restrictions on Operation of Day Care Facilities

“What I felt when they closed the day care facility? It was stress. And it still is. We had to organize something that worked well again. I didn’t know when it would end, how we should work with mum, so that what was achieved in Senior Plus [daily care home] wouldn’t be wasted. We share the care with our sister, but it can be difficult.” [Female Informal Carer, 65, Daughter, Interview 7]

“As we were closed and not able to meet with others, it just felt like prison. It was hard to handle.” [Female, Person with dementia, 82, Interview 1]

3.3.2. Access to Medical Help

“I haven’t had any revolution in my life because there are telephones and I could always call for help and ask. We also have clinics here, the health care team, which is very dynamic. They are even so determined to help patients that they took us in during a pandemic when my husband’s blood sugar was too high.” [Female Informal Carer, 77, Wife, Interview 19]

“I wish the access to medical care was better.” [Female, Person with dementia, 76, Interview 4]

3.3.3. Burden of Care

“If the carer has an institution where parents spend their time and suddenly this institution closes, then it has a negative effect on their organization of life, right?” [Female Informal Care, 58, Daughter, Interview 16]

“My daughter always said: ‘Mum, you are going out-don’t go out!’ So as to avoid this event.” [Female, Person with dementia, 70, Interview 5]

3.4. Theme 2: Psychological Response

3.4.1. Uncertainty and Anxiety

“It was very sad. I was lying on my bed and staring at the wall. Every day. How many people died and where? It was very sad. It lasted for so long.” [Female Informal Carer, 58, Daughter in-law, Interview 10]

“Well, I got a little stressed [with the lockdown], because it is a kind of burden. If I need something, some help, there is no way to get it. If I call a doctor, it is also impossible to get to him. And it’s even hard to get a prescription.” [Female, Person with dementia, 76, Interview 4]

3.4.2. Social Isolation

Literally, very soon after the day care facility was closed, my mother started to deteriorate in her health, especially the mental one. Her behaviours started to change, a lot of problems grew and for me it was a very big problem. I had to hire a private carer very quickly.” [Female Informal Carer, 58, Daughter, Interview 1]

“I am used to being lonely. Even before that virus I lived a life of a lonely person as I had been caring for my wife for 25 years.” [Male, Person with dementia, 87, Interview 2]

3.4.3. Adaptation and Coping

“If it weren’t for the optimism, we couldn’t deal with such problems.” [Female Carer, 75, Wife, Interview 9]

“I don’t mind wearing masks if it’s required.” [Male, Person with dementia, 87, Interview 2]

3.5. Theme 3: Emerging Needs

3.5.1. Institutional Support

“Regarding the psychosocial interventions, unfortunately it was very poor. It is true that from time to time, personnel [of daily care home] sent some links to on-line exercises, but my mother cannot use it. She can’t handle something like that, so it was unfortunately useless for her.” [Male, Informal Carer, 58, Son, Interview 15]

3.5.2. Social Support

“Of course, we are supported by friends and family. It would be hard without it. Or even hopeless.” [Female Informal Carer, 77, Wife, Interview 19]

“I have had thoughts how it’s going to be like and if I can handle it. But what turns out is that there are people who remember me. And they help. And this is very important for me. And that’s what they tell me: if you needed help, we would help you, just tell us.” [Female, Person with dementia, 75, Interview 3]

3.5.3. Remote Contacts

“It [on-line support for carers via communicators such as Zoom, Skype] is important. Because if there is no direct possibility, then you just have to look for a solution and undoubtedly some social media or some platforms that allow you to contact, (and see another person, because it is the human face that has the power), it is important. It is a form that may not be perfect, but it is good enough to be used.” [Female, Informal Carer, 60, Daughter, Interview 17]

“These teleconsultations… well, maybe they don’t quite meet my expectations. Actually, mine and my husband’s. Because we have a cold, for example, we want the doctor to see us, but to auscultate the throat, to take care of the patient in such a professional way.” [Female, Person with dementia, 70, Interview 5]

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data availability statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Theme 1: Care Re-Organization | |

| Shutdown or restrictions on operation of day care facilities | Dad used to commute [to the day care facility] himself, now he doesn’t leave the house alone… He had friends, he played cards, now he doesn’t… Male Informal Carer, 55, Son, Interview 20 Now we are divided into three groups, five-six people each. Our is 6 people. We are the artistic one. Generally, we are isolated.” Female, Person with dementia, 82, Interview 1 |

| Access to medical help | I would like to be able to call the clinic, because the pharmacist said that my father was given the same drug twice, under different names. I would like to consult a psychiatrist, but it is impossible, the phone is still busy… Male Informal Carer, 55, Son, Interview 20 During the coronavirus pandemic access to doctors’ care is extremely reduced as well as treating patients with anything different from coronavirus. Female Informal Carer, 75, Wife, Interview 9 There are problems because you have to wait a long time for registration: for an appointment or a prescription. You have to wait 4–5 days for a prescription. It takes four days to get a call from the doctor. So, there are troubles. Female, Person with dementia, 76, Interview 4 And this telemedicine… maybe it doesn’t quite meet my expectations. Actually, they are mine and my husband’s. For example, when we have a cold, we want the doctor to see us, we want him to listen, to examine our throats, to take care of the patient. Female, Person with dementia, 70, Interview 5 |

| Burden of care | When the pandemic broke out, the paid carer simply left, only me remained. I mean, the neighbours helped us and someone else from the family. But at this moment everything is on me. Male Informal Carer, 80, Husband, Interview 18 I was very burdened, I must say, both temporally and emotionally. Because I had to think about my household, to buy everything I needed, and about a household of my mother-in-law, because she did not always manage. It certainly had a negative impact on me, on my psyche as a carer… somehow negatively. Female Informal Carer, 60, Daughter-in-law, Interview 6 |

| Theme 2: Psychological response | |

| Uncertainty and anxiety | I felt that I would be burdened again. My sleep got worse and my GP gave me sleeping pills. Male Informal Carer, 55, Son, Interview 12 Now there is a relapse of this coronavirus. There are many cases. And the fear of going to the store, there it is. Female, Person with dementia, 70, Interview 5 |

| Social isolation | I was better, but my husband [person with dementia] felt he was locked in the house. He thought we were infected. Because of the TV news… he interpreted it that way. Even later, when you [the psychiatrist] said not to broadcast the news over and over again. Because, unfortunately, my husband learned that if he doesn’t come out, it means he has the coronavirus. But it must be said that the husband was emotionally disturbed that he could not go outside. He didn’t want to get out of bed. He still doesn’t want to. He acts as if he was sick… Female Informal Carer, 80, wife, Interview 5 Well, we were stuck indoors, we were staring at these four walls… Female, Person with dementia, 70, Interview 5 |

| Adaptation and coping | I don’t have negative [emotions]. I just had a task: not to let senior person to contact with other people. And I did it. Female Informal Carer, 58, Daughter, Interview 14 I very rarely went outside. If I went out, I would go out into the yard. Because I had such an opportunity that I could go out to my garden and sit, you know, in a nice surrounding. Female, Person with dementia, 75, Interview 3 |

| Theme 3: Emerging needs | |

| Institutional support | It would be very valuable if there were additional care at home, for example additional exercises, so that the father-in-law would start… Because I can see that it is getting harder and harder to get him out and lead to a bus stop. He feels so tired that I just drag him out. And I have no other choice, I don’t drive, my husband goes to work. So, I just bring him to my flat with just enough effort to keep an eye on him here. To keep him awake all the time, to exercise with him or something. A little bit of extra care at home would certainly come in handy. Informal Carer, 60 years old, daughter-in-law, Interview 6 |

| Social support | Sometimes it happens that I have some moments of weakness, but my sister puts me upright, sometimes I put her upright and we support each other somehow. Female Informal Carer, 60, Daughter, Interview 17 I went to get a newspaper, something like that, but I wasn’t shopping. My children were doing it for me. I didn’t even cook because they brought me dinners. So, I had a luxury!” Female, Person with dementia, 82, Interview 1 |

| Remote contacts | [Teleconsultations] are quite difficult to put into everyday practice, as, firstly, she is not fluent in it and moreover she does not like remote options. Male Informal Carer, 57, Son, Interview 8 We had more time for ourselves, more time for the garden. In fact, I missed Easter the most, so we spent our time at the laptop. We also shared eggs virtually for Easter. Reunited into three families. Well, we made it! Female Informal Carer, 77, Wife, Interview 19 |

References

- Vernooij-Dassen, M.; Verhey, F.; Lapid, M. The risks of social distancing for older adults: A call to balance. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2020, 32, 1235–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzheimer Europe Board. Alzheimer Europe Recommendations on Promoting the Wellbeing of People with Dementia and Carers during the COVID-19 Pandemic n.d. Available online: https://www.alzheimer-europe.org/Policy/Our-opinion-on/2020-Wellbeing-of-people-with-dementia-during-COVID-19-pandemic (accessed on 23 January 2021).

- Numbers, K.; Brodaty, H. The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on people with dementia. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2021, 17, 69–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curnow, E.; Rush, R.; Maciver, D.; Górska, S.; Forsyth, K. Exploring the needs of people with dementia living at home reported by people with dementia and informal caregivers: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. Aging Ment. Health 2019, 25, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Azarpazhooh, M.R.; Amiri, A.; Morovatdar, N.; Steinwender, S.; Rezaei Ardani, A.; Yassi, N.; Biller, J.; Stranges, S.; Belasi, M.T.; Neya, S.K.; et al. Correlations between COVID-19 and burden of dementia: An ecological study and review of literature. J. Neurol. Sci. 2020, 416, 117013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łuc, M.; Szcześniak, D.; Trypka, E.; Mazurek, J.; Rymaszewska, J. SARS-CoV-2 pandemic and the population with dementia. Recommendations under the auspices of the Polish Psychiatric Association. Psychiatr. Pol. 2020, 54, 421–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-González, A.; Rajagopalan, J.; Livingston, G.; Alladi, S. The effect of COVID-19 isolation measures on the cognition and mental health of people living with dementia: A rapid systematic review of one year of quantitative evidence. EClinicalMedicine 2021, 39, 101047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, G.; Russo, M.J.; Campos, J.A.; Allegri, R.F. Living with dementia: Increased level of caregiver stress in times of COVID-19. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2020, 32, 1377–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernooij-Dassen, M.; Moniz-Cook, E.; Jeon, Y.H. Social health in dementia care: Harnessing an applied research agenda. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2018, 30, 775–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Vugt, M.; Dröes, R.M. Social health in dementia. Towards a positive dementia discourse. Aging Ment. Health 2017, 21, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huber, M.; André Knottnerus, J.; Green, L.; Van Der Horst, H.; Jadad, A.R.; Kromhout, D.; Leonard, B.; Lorig, K.; Loureiro, M.I.; van der Meer, J.W.M.; et al. How should we define health? BMJ 2011, 343, d4163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dröes, R.M.; Chattat, R.; Diaz, A.; Gove, D.; Graff, M.; Murphy, K.; Verbeek, H.; Vernooij-Dassen, M.; Clare, L.; Johannessen, A.; et al. Social health and dementia: A European consensus on the operationalization of the concept and directions for research and practice. Aging Ment. Health 2017, 21, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vernooij-Dassen, M.; Moniz-Cook, E.; Verhey, F.; Chattat, R.; Woods, B.; Meiland, F.; Franco, M.; Holmerova, I.; Orrell, M.; De Vugt, M. Bridging the divide between biomedical and psychosocial approaches in dementia research: The 2019 INTERDEM manifesto. Aging Ment. Health 2021, 25, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadowska, A. Organizacja opieki nad chorymi na chorobę Alzheiemre w Polsce [Orgaization of care for patients with Alzheimer’s disease in Poland]. In Sytuacja Osób Chorych na Chorobę Alzheimera w Polsce. Raport RPO [The Situation of People with Alzheimer’s Disease in Poland. Report of the Ombudsman], 2nd ed.; Szczudlik, A., Ed.; Biuro Rzecznika Praw Obywatelskich: Warsaw, Poland, 2016; pp. 42–46. [Google Scholar]

- Szcześniak, D.; Dröes, R.M.; Meiland, F.; Brooker, D.; Farina, E.; Chattat, R.; Evans, S.B.; Evans, S.C.; Saibene, F.L.; Urbańska, K.; et al. Does the community-based combined Meeting Center Support Programme (MCSP) make the pathway to day-care activities easier for people living with dementia? A comparison before and after implementation of MCSP in three European countries. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2018, 30, 1717–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mazurek, J.; Szcześniak, D.; Lion, K.M.; Dröes, R.M.; Karczewski, M.; Rymaszewska, J. Does the meeting centres support programme reduce unmet care needs of community-dwelling older people with dementia? A controlled, 6-month follow-up Polish study. Clin. Interv. Aging 2019, 14, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miranda-Castillo, C.; Woods, B.; Galboda, K.; Oomman, S.; Olojugba, C.; Orrell, M. Unmet needs, quality of life and support networks of people with dementia living at home. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2010, 8, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Durda, M. Organizacja opieki nad osobami z demencją w Polsce na tle krajów rozwiniętych i rozwijających się. Gerontol Pol. 2010, 18, 76–85. [Google Scholar]

- Rusowicz, J.; Pezdek, K.; Szczepańska-Gieracha, J. Needs of alzheimer’s charges’ caregivers in poland in the COVID-19 pandemic—An observational study. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miejskie Centrum Usług Socjalnych we Wrocławiu, n.d. Available online: https://www.mcus.pl/projekty/projekt-moj-drugi-dom/aktualnosci.html (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Advice for the Public n.d. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public (accessed on 23 February 2021).

- Sutcliffe, C.; Giebel, C.; Bleijlevens, M.; Lethin, C.; Stolt, M.; Saks, K.; Soto, M.E.; Meyer, G.; Zabalegui, A.; Chester, H.; et al. Caring for a Person With Dementia on the Margins of Long-Term Care: A Perspective on Burden From 8 European Countries. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2017, 18, 967–973.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Y.; Connell, L.S.M.; Rajpara, A.R.; Hodgson, N.A. Impact of COVID-19 on Dementia Caregivers and Factors Associated With their Anxiety Symptoms. Am. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. Other Demen 2021, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzheimer Europe. COVID-19—Living with Dementia n.d. Available online: https://www.alzheimer-europe.org/Living-with-dementia/COVID-19 (accessed on 29 January 2021).

- Hughes, M.C.; Liu, Y.; Baumbach, A. Impact of COVID-19 on the Health and Well-being of Informal Caregivers of People with Dementia: A Rapid Systematic Review. Gerontol. Geriatr. Med. 2021, 7, 7728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinquart, M.; Sörensen, S. Spouses, Adult Children, and Children-in-Law as Caregivers of Older Adults: A Meta-Analytic Comparison. Psychol. Aging 2011, 26, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brodaty, H.; Donkin, M. Family caregivers of people with dementia. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2009, 11, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.T. Dementia Caregiver Burden: A Research Update and Critical Analysis. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2017, 19, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Keng, A.; Brown, E.E.; Rostas, A.; Rajji, T.K.; Pollock, B.G.; Mulsant, B.H.; Kumar, S. Effectively Caring for Individuals With Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 573367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, D.; Paul, G.; Fahy, M.; Dowling-Hetherington, L.; Kroll, T.; Moloney, B.; Duffy, C.; Fealy, G.; Lafferty, A. The invisible workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic: Family carers at the frontline [version 1; peer review: 2 approved]. HRB Open Res. 2020, 3, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altieri, M.; Santangelo, G. The Psychological Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic and Lockdown on Caregivers of People With Dementia. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2021, 29, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aledeh, M.; Habib Adam, P. Caring for Dementia Caregivers in Times of the COVID-19 Crisis: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Nurs. Res. 2020, 8, 552–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giebel, C.; Lord, K.; Cooper, C.; Shenton, J.; Cannon, J.; Pulford, D.; Shaw, L.; Gaughan, A.; Tetlow, H.; Butchard, S.; et al. A UK survey of COVID-19 related social support closures and their effects on older people, people with dementia, and carers. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2020, 36, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Cruz, M.; Banerjee, D. Caring for Persons Living With Dementia During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Advocacy Perspectives From India. Front Psychiatry 2020, 11, 603231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Li, T.; Barbarino, P.; Gauthier, S.; Brodaty, H.; Molinuevo, J.L.; Xie, H.; Sun, Y.; Yu, E.; Tang, Y.; et al. Dementia care during COVID-19. Lancet 2020, 395, 1190–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giebel, C.; Cannon, J.; Hanna, K.; Butchard, S.; Eley, R.; Gaughan, A.; Komuravelli, A.; Shenton, J.; Callaghan, S.; Tetlow, H.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 related social support service closures on people with dementia and unpaid carers: A qualitative study. Aging Ment. Health 2020, 25, 1281–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giebel, C.; Hanna, K.; Cannon, J.; Eley, R.; Tetlow, H.; Gaughan, A.; Komuravelli, A.; Shenton, J.; Rogers, C.; Butchard, S.; et al. Decision-making for receiving paid home care for dementia in the time of COVID-19: A qualitative study. BMC Geriatr 2020, 20, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- King, N. Using Templates in the Thematic Analysis of Text. In Essential Guide to Qualitative Methods in Organizational Research; Cassels, C., Symon, G., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2004; pp. 256–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, D.L. From themes to hypotheses: Following up with quantitative methods. Qual. Health Res. 2015, 25, 789–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Population Stat—World Statistical Data: Wroclaw, Poland Population n.d. Available online: https://populationstat.com/poland/wroclaw (accessed on 23 February 2021).

- World Health Organisation: Process of Translation and Adaptation of Instruments n.d. Available online: https://www.who.int/substance_abuse/research_tools/translation/en/ (accessed on 23 February 2021).

- Kalfoss, M. Translation and Adaption of Questionnaires: A Nursing Challenge. SAGE Open Nurs. 2019, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Talbot, C.V.; Briggs, P. “Getting back to normality seems as big of a step as going into lockdown”: The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on People with Early-Middle Stage Dementia. Age Ageing 2021, 50, 657–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thyrian, J.R.; Kracht, F.; Nikelski, A.; Boekholt, M.; Schumacher-Schönert, F.; Rädke, A.; Michalowsky, B.; Christian, H.V.; Hoffmann, W.; Rodriguez, F.S.; et al. The Situation of Elderly with Cognitive Impairment Living at Home during Lockdown in the Corona-Pandemic in Germany. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roach, P.; Zwiers, A.; Cox, E.; Fischer, K.; Charlton, A.; Josephson, C.B.; Patten, S.B.; Seitz, D.; Ismail, Z.; E Smith, E. Understanding the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on well-being and virtual care for people living with dementia and care partners living in the community. Dementia 2020, 20, 2007–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giebel, C.; Pulford, D.; Cooper, C.; Lord, K.; Shenton, J.; Cannon, J.; Shaw, L.; Tetlow, H.; Limbert, S.; Callaghan, S.; et al. COVID-19-related social support service closures and mental well-being in older adults and those affected by dementia: A UK longitudinal survey. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e045889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koronawirus. Rzecznik Wskazuje MZ Najważniejsze Problemy Systemu Ochrony Zdrowia do Rozwiązania n.d. Available online: https://www.rpo.gov.pl/pl/content/koronawirus-rpo-najwazniejsze-problemy-systemu-ochrony-zdrowia (accessed on 23 February 2021).

- Savla, J.; Roberto, K.A.; Blieszner, R.; McCann, B.R.; Hoyt, E.; Knight, A.L. Dementia caregiving during the “stay-at-home” phase of COVID-19 pandemic. J. Gerontol. Ser. B. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mok, V.C.T.; Pendlebury, S.; Wong, A.; Alladi, S.; Au, L.; Bath, P.M.; Biessels, G.J.; Chen, C.; Cordonnier, C.; Dichgans, M.; et al. Tackling challenges in care of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias amid the COVID-19 pandemic, now and in the future. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2020, 16, 1571–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Beyond Containment: Health systems responses to COVID-19 in the OECD. Tackling Coronavirus Contrib a Glob Effort. Available online: https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=119_119689-ud5comtf84&title=Beyond_Containment:Health_system_responses_to_COVID-19_in_the_OECD (accessed on 23 September 2021).

- Zwerling, J.L.; Cohen, J.A.; Verghese, J. Dementia and caregiver stress. Neurodegener Dis. Manag. 2016, 6, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dening, K.H.; Lloyd-Williams, M. Minimising long-term effect of COVID-19 in dementia care. Lancet 2020, 396, 957–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz-Dant, K.; Comas-Herrera, A. The impacts of COVID-19 on unpaid carers of adults with long-term care needs and measures to address these impacts: A rapid review of the available evidence up to November 2020. J. Long-Term Care 2021, 2021, 124–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duggan, S.; Blackman, T.; Martyr, A.; Van Schaik, P. The impact of early dementia on outdoor life: A “shrinking world”? Dementia 2008, 7, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brittain, K.; Corner, L.; Robinson, L.; Bond, J. Ageing in place and technologies of place: The lived experience of people with dementia in changing social, physical and technological environments. Sociol. Health Illn. 2010, 32, 272–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yates, L.; Csipke, E.; Moniz-Cook, E.; Leung, P.; Walton, H.; Charlesworth, G.; Spector, A.; Hogervorst, E.; Mountain, G.; Orrell, M. The development of the promoting independence in dementia (PRIDE) intervention to enhance independence in dementia. Clin. Interv. Aging 2019, 14, 1615–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Von Kutzleben, M.; Schmid, W.; Halek, M.; Holle, B.; Bartholomeyczik, S. Community-dwelling persons with dementia: What do they need? What do they demand? What do they do? A systematic review on the subjective experiences of persons with dementia. Aging Ment. Health 2012, 16, 378–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schölzel-Dorenbos, C.J.M.; Meeuwsen, E.J.; Olde Rikkert, M.G.M. Integrating unmet needs into dementia health-related quality of life research and care: Introduction of the Hierarchy Model of Needs in Dementia. Aging Ment. Health 2010, 14, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monahan, C.; Macdonald, J.; Lytle, A.; Apriceno, M.B.; Levy, S.R. COVID-19 and Ageism: How positive and negative responses impact older adults and society. Am. Psychol. 2020, 75, 887–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manca, R.; De Marco, M.; Venneri, A. The Impact of COVID-19 Infection and Enforced Prolonged Social Isolation on Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in Older Adults With and Without Dementia: A Review. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 585540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, G.; Peri, K. Challenges to dementia care during COVID-19: Innovations in remote delivery of group Cognitive Stimulation Therapy. Aging Ment. Health 2020, 25, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simonetti, A.; Pais, C.; Jones, M.; Cipriani, M.C.; Janiri, D.; Monti, L.; Landi, F.; Bernabei, R.; Liperoti, R.; Sani, G. Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in Elderly With Dementia During COVID-19 Pandemic: Definition, Treatment, and Future Directions. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 579842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanna, K.; Giebel, C.; Tetlow, H.; Ward, K.; Shenton, J.; Cannon, J.; Komuravelli, A.; Gaughan, A.; Eley, R.; Rogers, C.; et al. Emotional and Mental Wellbeing Following COVID-19 Public Health Measures on People Living With Dementia and Carers. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 2021, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canevelli, M.; Valletta, M.; Toccaceli Blasi, M.; Remoli, G.; Sarti, G.; Nuti, F.; Sciancalepore, F.; Ruberti, E.; Cesari, M.; Bruno, G. Facing Dementia During the COVID-19 Outbreak. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2020, 68, 1673–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerritsen, D.L.; Voshaar, R.C.O. The effects of the COVID-19 virus on mental healthcare for older people in the Netherlands. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2020, 32, 1353–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muntsant, A.; Giménez-Llort, L. Impact of Social Isolation on the Behavioral, Functional Profiles, and Hippocampal Atrophy Asymmetry in Dementia in Times of Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19): A Translational Neuroscience Approach. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 572583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziggi, I.S.; EJose, P.; Cornwell, E.Y.; Madsen, K.R.; Koushede, V.; MD, A.K.; Nielsen, L.; Koyanagi, A.; Koushede, V. Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and symptoms of depression and anxiety among older Americans (NSHAP): A longitudinal mediation analysis. Lancet Public Health 2020, 5, e62–e70. [Google Scholar]

- Lara, B.; Carnes, A.; Dakterzada, F.; Benitez, I.; Piñol-Ripoll, G. Neuropsychiatric symptoms and quality of life in Spanish patients with Alzheimer’s disease during the COVID-19 lockdown. Eur. J. Neurol. 2020, 27, 1744–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, T.J.; Rabheru, K.; Peisah, C.; Reichman, W.; Ikeda, M. Loneliness and social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2020, 32, 1217–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Shea, E. Remembering people with dementia during the COVID-19 crisis. HRB Open Res. 2020, 3, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Giebel, C.; Hanna, K.; Rajagopal, M.; Komuravelli, A.; Cannon, J.; Shenton, J.; Eley, R.; Gaughan, A.; Callaghan, S.; Tetlow, H.; et al. The potential dangers of not understanding COVID-19 public health restrictions in dementia: “It’s a groundhog day—Every single day she does not understand why she can’t go out for a walk” n.d. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arlt, S.; Lindner, R.; Rösler, A.; Von Renteln-Kruse, W. Adherence to medication in patients with dementia: Predictors and strategies for improvement. Drugs Aging 2008, 25, 1033–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long-Term Senior Policy in Poland for the Years 2014–2020 in Outline n.d. Available online: https://das.mpips.gov.pl/source/Long-termSeniorPolicy.pdf (accessed on 23 February 2021).

- Arighi, A.; Fumagalli, G.G.; Carandini, T.; Pietroboni, A.M.; De Riz, M.A.; Galimberti, D.; Scarpini, E. Facing the digital divide into a dementia clinic during COVID-19 pandemic: Caregiver age matters. Neurol. Sci. 2021, 42, 1247–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kańtoch, E.; Kańtoch, A. What features and functions are desired in telemedical services targeted at polish older adults delivered by wearable medical devices?—Pre-COVID-19 flashback. Sensors 2020, 20, 5181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabbiadini, A.; Baldissarri, C.; Durante, F.; Valtorta, R.R.; De Rosa, M.; Gallucci, M. Together Apart: The Mitigating Role of Digital Communication Technologies on Negative Affect During the COVID-19 Outbreak in Italy. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 554678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canale, N.; Marino, C.; Lenzi, M.; Vieno, A.; Griffiths, M.D.; Gaboardi, M.; Girado, M.; Cervone, C.; Santinello, M. How communication technology fosters individual and social wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic: Preliminary support for a digital interaction model. J. Happiness Stud. 2021, 2021, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garfin, D.R. Technology as a coping tool during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: Implications and recommendations. Stress Health 2020, 36, 555–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuffaro, L.; Di Lorenzo, F.; Bonavita, S.; Tedeschi, G.; Leocani, L.; Lavorgna, L. Dementia care and COVID-19 pandemic: A necessary digital revolution. Neurol. Sci. 2020, 41, 1977–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doraiswamy, S.; Abraham, A.; Mamtani, R.; Cheema, S. Use of telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic: Scoping review. J. Med. Internet. Res. 2020, 22, e24087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moyle, W. The promise of technology in the future of dementia care. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2019, 15, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| N (%) | People with Dementia (n = 5) | Informal Carers (n = 21) | Total Sample (n = 26) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Female | 4 (80%) | 13 (61.9%) | 17 (65.4%) |

| Male | 1 (20%) | 8 (38.1%) | 9 (34.6%) |

| Relationship with PLWD | |||

| Spouse | - | 6 (28.6%) | - |

| Adult child | - | 15 (71.4%) | - |

| Living with PLWD | |||

| Yes | - | 13 (61.9%) | - |

| No | - | 8 (38.1%) | - |

| Dementia subtype | |||

| Alzheimer’s disease | 2 (40%) | 8 (38.1%) | 10 (38.5%) |

| Mixed dementia | 2 (40%) | 6 (28.6%) | 8 (30.8%) |

| Vascular dementia | 0 (0%) | 4 (19%) | 4 (15.4%) |

| Not specified | 1 (20%) | 2 (9.5%) | 3 (11.5%) |

| Dementia in Parkinson’s disease | 0 (0%) | 1 (4.8%) | 1 (3.8%) |

| Mean (SD), [Range] | |||

| Age | 78 (+/−6.6) (70–87) | * 81.5 (+/−4.7) (75–85) ** 63.1 (+/−9.9) (52–80) | 80.8 (+/−5.14) (70–87) |

| Years of education | 10.8 (+/−1.64) (9–12) | 12.9 (+/−2.92) (9–17) | 12.5 (+/−2.82) (9–17) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maćkowiak, M.; Senczyszyn, A.; Lion, K.; Trypka, E.; Małecka, M.; Ciułkowicz, M.; Mazurek, J.; Świderska, R.; Giebel, C.; Gabbay, M.; et al. The Experiences of People with Dementia and Informal Carers Related to the Closure of Social and Medical Services in Poland during the COVID-19 Pandemic—A Qualitative Study. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1677. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9121677

Maćkowiak M, Senczyszyn A, Lion K, Trypka E, Małecka M, Ciułkowicz M, Mazurek J, Świderska R, Giebel C, Gabbay M, et al. The Experiences of People with Dementia and Informal Carers Related to the Closure of Social and Medical Services in Poland during the COVID-19 Pandemic—A Qualitative Study. Healthcare. 2021; 9(12):1677. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9121677

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaćkowiak, Maria, Adrianna Senczyszyn, Katarzyna Lion, Elżbieta Trypka, Monika Małecka, Marta Ciułkowicz, Justyna Mazurek, Roksana Świderska, Clarissa Giebel, Mark Gabbay, and et al. 2021. "The Experiences of People with Dementia and Informal Carers Related to the Closure of Social and Medical Services in Poland during the COVID-19 Pandemic—A Qualitative Study" Healthcare 9, no. 12: 1677. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9121677

APA StyleMaćkowiak, M., Senczyszyn, A., Lion, K., Trypka, E., Małecka, M., Ciułkowicz, M., Mazurek, J., Świderska, R., Giebel, C., Gabbay, M., Rymaszewska, J., & Szcześniak, D. (2021). The Experiences of People with Dementia and Informal Carers Related to the Closure of Social and Medical Services in Poland during the COVID-19 Pandemic—A Qualitative Study. Healthcare, 9(12), 1677. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9121677