Perception of Medical Professionalism among Medical Residents in Spain

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

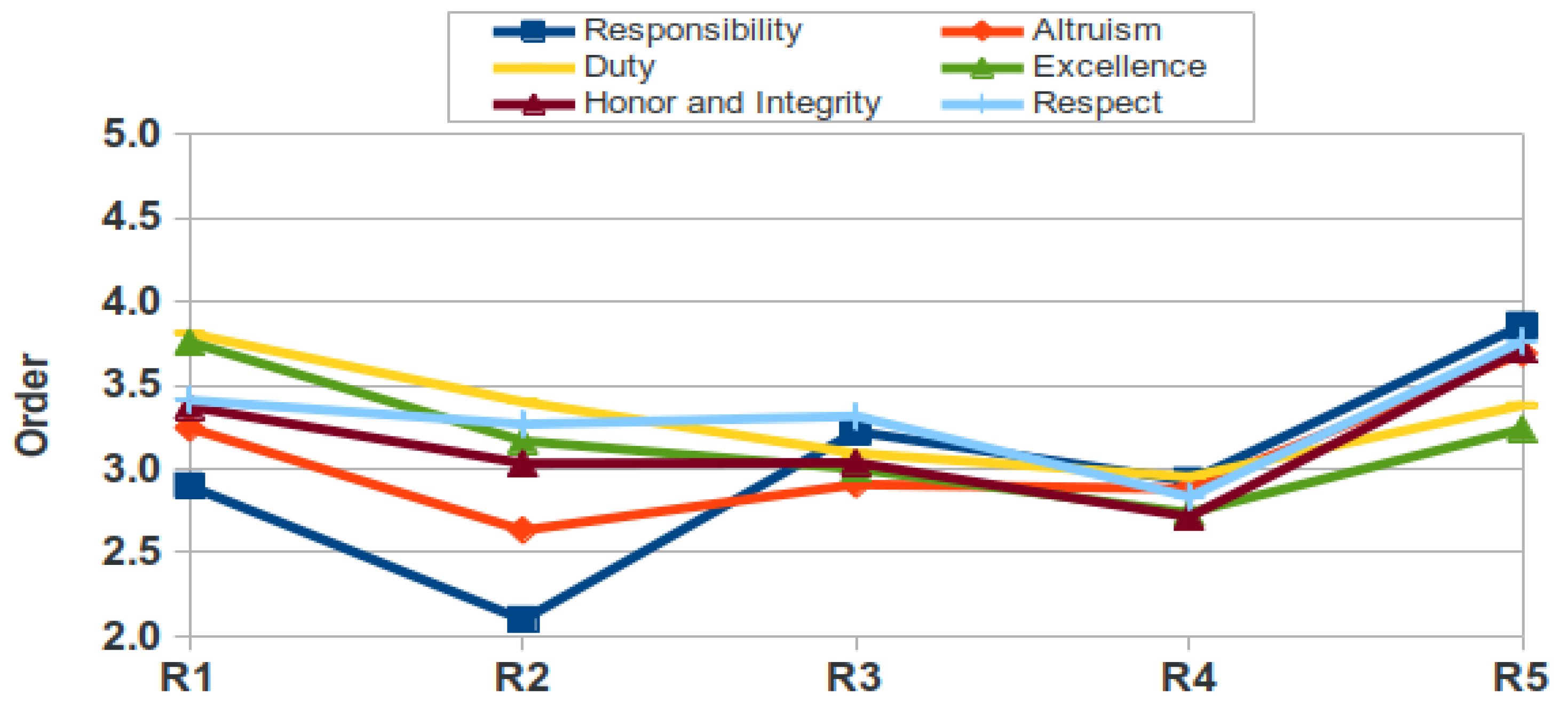

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huelmos, A.I. El Renacer Del Profesionalismo Medico. Available online: https://secardiologia.es/comunicacion/noticias-sec/10978-el-renacer-del-profesionalismo-medico (accessed on 10 December 2020). (In Spanish).

- Giménez, N.; Alcaraz, J.; Gavagnach, M.; Kazan, R.; Arévalo, A.; Rodríguez-Carballeira, M. Profesionalismo: Valores y competencias en formación sanitaria especializada. Rev. Calid. Asist. 2017, 32, 226–233. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacomantone, O.; Suárez, I. Medical professionalism, its relationship to 21st century medical education. Educ. Médica Perm. 2009, 1, 4–18. Available online: http://sedici.unlp.edu.ar/bitstream/handle/10915/8517/profesionalismo_medico.pdf; (accessed on 11 November 2021). (In Spanish).

- Rodriguez Sendin, J.J. Definition of “Medical Profession”, “Medical Professional” and “Medical Professionalism”. Educ. Med. 2010, 13, 63–66, (In Spanish and English). [Google Scholar]

- Merino, J. Profesionalismo o profesionalidad médica. Educ. Med. 2015, 16, 29–32. Available online: https://www.elsevier.es/es-revista-educacion-medica-71-articulo-profesionalismo-o-profesionalidad-medica-X1575181315352408 (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- Millán Núnez-Cortés, J. Physician’s values for quality practice: Professionalism. FEM 2014, 17 (Suppl. 1), S23–S25. Available online: http://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2014-98322014000500003 (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- Prieto-Miranda, S.; Jiménez-Bernardino, C.A.; Monjaraz-Guzmán, E.G.; Esparza-Pérez, R.I. Professionalism in physicians in a second-level hospital. In Rev. Médica Inst. Mex. Seguro Soc.; 2017; 55, pp. 264–272. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28296379 (accessed on 11 November 2021). (In Spanish)

- Gutiérrez, C.I. Percepción de Internos y Residentes de Aspectos del Profesionalismo Médico en Establecimientos de Salud. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Católica Santo Toribio De Mogrovejo, Chiclayo, Perú, 2013. Available online: http://tesis.usat.edu.pe/xmlui/bitstream/handle/20.500.12423/552/tm_gutierrez_gutierrez_carmenisabel.pdf? (accessed on 11 November 2021). (In Spanish).

- Serrano-Costa, B.; Flores-Funes, D.; Botella-Martínez, C.; Atucha, N.M.; García-Estañ, J. Medical professionalism perception of medical students in spain. Med. Univ. 2020, 3, 119–126. Available online: https://www.um.es/documents/1935287/7834098/Medical+Professionalism+Perception+of+Medical+Students+in+Spain.pdf/982d4a3e-7e3c-a56a-a8c6-882d829a24b5?t=1637225729700 (accessed on 11 November 2021). [CrossRef]

- Working Party of the Royal College of Physicians. Doctors in society. Medical professionalism in a changing world. Clin. Med. (Lond.) 2005, 5 (Suppl. 1), S5–S40. [Google Scholar]

- García-Estañ, J. Studying Medicine and being a doctor in Spain. MedEdPublish 2018, 7, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante, E.; Sanabria, A. Evaluation of attitudes towards professionalism in medical students. Rev. Colomb. Cir. 2014, 29, 222–229. Available online: http://www.scielo.org.co/pdf/rcci/v29n3/v29n3a7.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2021). (In Spanish).

- ABIM Foundation. American Board of Internal Medicine; ACP–ASIM Foundation. American College of Physicians–American Society of Internal Medicine; European Federation of Internal Medicine. Medical professionalism in the new millennium: A physician charter. Ann. Intern. Med. 2002, 136, 243–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphries, N.; McDermott, A.M.; Creese, J.; Matthews, A.; Conway, E.; Byrne, J.-P. Hospital Doctors in Ireland and the Struggle for Work-Life Balance. Eur. J. Public Health 2020, 30, iv32–iv35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanafelt, T.D.; West, C.P.; Sinsky, C.; Trockel, M.; Tutty, M.; Satele, D.V.; Carlasare, L.E.; Dyrbye, L.N. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life integration in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2017. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2019, 94, 1681–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goyal, R.C. Research Methodology for Health Professionals Including Proposal, Thesis and Article Writing; Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers: New Delhi, India, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan, N.; Corrigan, O.; Allard, J.; Archer, J.; Barnes, R.; Bleakley, A.; Collett, T.; De Bere, S.R. The transition from medical student to junior doctor: Today’s experiences of Tomorrow’s Doctors. Med. Educ. 2010, 44, 449–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kebede, S.; Gebremeskel, B.; Yekoye, A.; Menlkalew, Z.; Asrat, M.; Medhanyie, A.A. Medical professionalism: Perspectives of medical students and residents at Ayder Comprehensive and Specialized Hospital, Mekelle, Ethiopia—A cross-sectional study. Adv. Med. Educ. Pract. 2018, 9, 611–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Govindaraja, C.; Ramachandran, G.; Ko Ko Min, A. The Ecology of Medical Professionalism: Perceived and Emulated, What matters? MedEDPublish 2016, 2. Available online: https://www.mededpublish.org/manuscripts/590 (accessed on 10 November 2020). [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wynia, M.K.; Latham, S.R.; Kao, A.C.; Berg, J.W.; Emanuel, L.L. Medical Professionalism in Society. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 341, 1612–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Ruiz, J. Comprehensive training and medical professionalism: A proposal for work in the classroom. Educ. Med. 2009, 12, 73–82. Available online: http://scielo.isciii.es/pdf/edu/v12n2/colaboracion2.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2021). (In Spanish).

- Self, D.J.; Baldwin, D.C., Jr. Does medical education inhibit the development of moral reasoning in medical students? A cross-sectional study. Acad. Med. 1998, 73 (Suppl. 10), S91–S93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, S.; Farnan, J.; Yoon, J.; Leo, T.; Upadhyay, G.A.; Humphrey, H.J.; Arora, V.M. Third year medical students and unprofessional behaviors. Acad. Med. 2007, 82 (Suppl. 10), 535–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, B.W.; Barber, L.; Clardy, J.; Leveland, E.C.; O’Sullivan, P. Is there a hardening of the heart during medical school? Acad. Med. 2008, 83, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, S.; Howard, B.; Schlussel, Y.R.; Herrigel, D.; Smolarz, B.G.; Gable, B.; Vasquez, J.; Grigo, H.; Kaufman, M. Humanism at heart: Preserving empathy in third-year medical students. Acad. Med. 2011, 86, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birden, H.; Glass, N.; Wilson, I.; Harrison, M.; Usherwood, T.; Nass, D. Teaching professionalism in medical education: A Best Evidence Medical Education (BEME) systematic review. Med. Teach. 2013, 35, e1252–e1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Eraky, M.M. Twelve Tips for teaching medical professionalism at all levels of medical education. Med. Teach. 2015, 37, 1018–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadakis, M.A.; Hodgson, C.S.P.; Teherani, A.P.; Kohatsu, N. Unprofessional behavior in medical school is associated with subsequent disciplinary action by a state medical board. Acad. Med. 2004, 79, 244–249. Available online: https://journals.lww.com/academicmedicine/Fulltext/2004/03000/%20Our_Compact_with_Tomorrow_s_Doctors.11.aspx (accessed on 11 November 2021). [CrossRef]

- Hafferty, F.W.; Franks, R. The hidden curriculum, ethics teaching, and the structure of medical education. Acad. Med. 1994, 69, 861–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coulehan, J.; Williams, P.C. Vanquishing virtue: The impact of medical education. Acad. Med. 2001, 76, 598–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, C.S.; Delgado, E.M.; Barg, F.K.; Posner, J.C. Resident perspectives on professionalism lack common consensus. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2014, 63, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krain, L.P.; Lavelle, E. Residents’ perspectives on professionalism. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2009, 1, 221–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mahood, S.C. Medical education: Beware the hidden curriculum. In Can. Fam. Physician; 2011; 57, pp. 983–985. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3173411/ (accessed on 11 November 2021). [PubMed]

- Jauregui, J.; Gatewood, M.O.; Ilgen, J.S.; Schaninger, C.; Strote, J. Emergency Medicine Resident Perceptions of Medical Professionalism. West. J. Emerg. Med. 2016, 17, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratanawongsa, N.; Bolen, S.; Howell, E.E.; Kern, D.E.; Sisson, S.D.; Larriviere, D. Residents’ perceptions of professionalism in training and practice: Barriers, promoters, and duty hour requirements. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2006, 21, 758–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghari, F.; Fard, N.N.; Atabaki, A. Are we proper role models for students? Interns’ perception of faculty and residents’ professional behaviour. Postgrad. Med. J. 2011, 87, 519–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brissette, M.D.; Johnson, K.A.; Raciti, P.M.; McCloskey, C.B.; Gratzinger, D.A.; Conran, R.M.; Domen, R.E.; Hoffman, R.D.; Post, M.D.; Roberts, C.A.; et al. Perceptions of Unprofessional Attitudes and Behaviors: Implications for Faculty Role Modeling and Teaching Professionalism During Pathology Residency. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2017, 141, 1394–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Ding, N.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wen, D. Assessing medical professionalism: A systematic review of instruments and their measurement properties. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0177321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, T.E. Teaching, learning and evaluating professionalism: The greatest challenge of all. FEM 2017, 20. Available online: http://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_abstract&pid=S2014-98322017000200002 (accessed on 11 November 2021). (In Spanish).

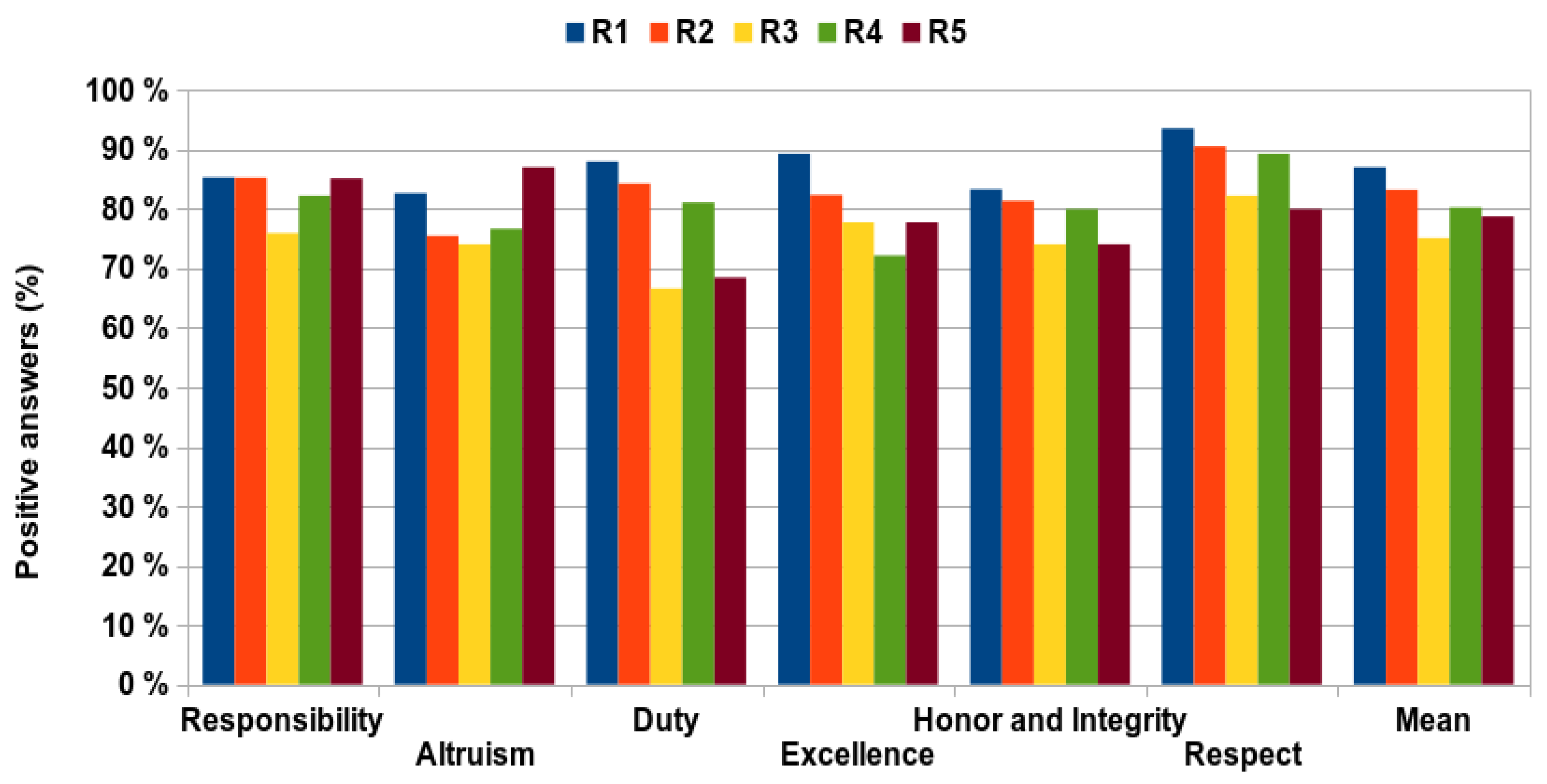

| Categories | Students | Residents |

|---|---|---|

| Responsibility | 84.97% ± 0.04 | 82.79% ± 0.04 |

| Altruism | 89.17% ± 0.04 | 79.19% ± 0.05 |

| Duty | 76.77% ± 0.05 | 77.72% ± 0.08 |

| Excellence | 74.61% ± 0.06 | 79.89% ± 0.04 |

| Honor and Integrity | 82.51% ± 0.07 | 78.57% ± 0.03 |

| Respect | 90.08% ± 0.05 | 87.15% ± 0.05 |

| Mean | 83.02% ± 0.05 | 80.89% ± 0.05 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

García-Estañ, J.; Cabrera-Maqueda, J.M.; González-Lozano, E.; Fernández-Pardo, J.; Atucha, N.M. Perception of Medical Professionalism among Medical Residents in Spain. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1580. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9111580

García-Estañ J, Cabrera-Maqueda JM, González-Lozano E, Fernández-Pardo J, Atucha NM. Perception of Medical Professionalism among Medical Residents in Spain. Healthcare. 2021; 9(11):1580. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9111580

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcía-Estañ, Joaquín, Jose María Cabrera-Maqueda, Eduardo González-Lozano, Jacinto Fernández-Pardo, and Noemí M. Atucha. 2021. "Perception of Medical Professionalism among Medical Residents in Spain" Healthcare 9, no. 11: 1580. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9111580

APA StyleGarcía-Estañ, J., Cabrera-Maqueda, J. M., González-Lozano, E., Fernández-Pardo, J., & Atucha, N. M. (2021). Perception of Medical Professionalism among Medical Residents in Spain. Healthcare, 9(11), 1580. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9111580