Moral Distress in Community and Hospital Settings for the Care of Elderly People. A Grounded Theory Qualitative Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling

2.2. Structure of the Interviews

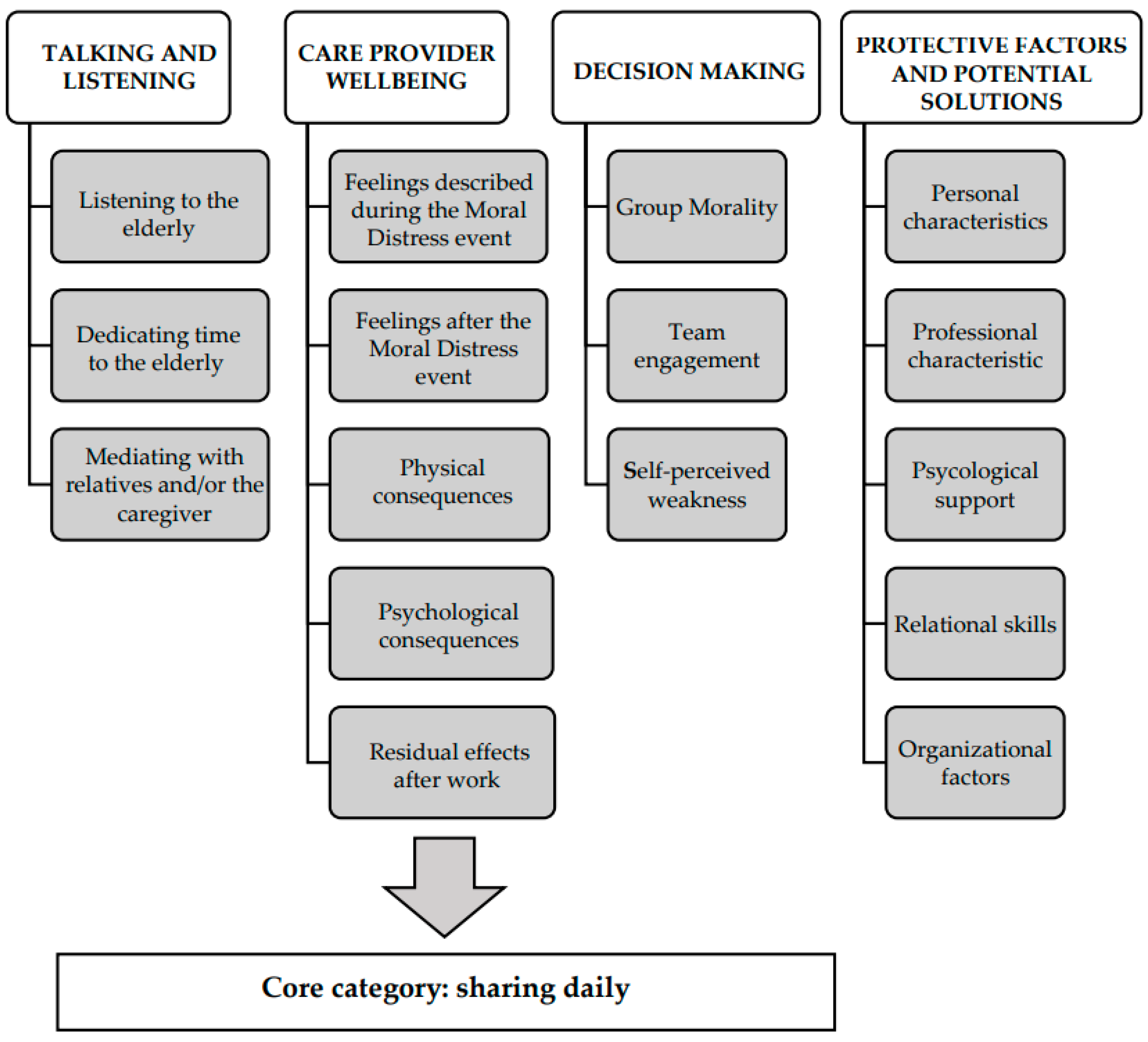

3. Results

3.1. Talking and Listening

3.1.1. Listening to the Elderly

“From the human point of view [older people] have relationship needs because often [they are] lonely people and so they often want to chat and to exchange ideas, opinions; to tell each other. And, they need attention.”[ID 6]

“Someone to explain to them how to cope with life with their illness.”[ID 3]

“Sometimes, for example, the patient would ask me to simply spend some time together, for some company.”[ID 2]

3.1.2. Dedicating Time to the Elderly

“An elderly man was, unfortunately, going to die, and I could not devote time to him. I was not close to him in such a delicate moment, when he was alone, no family and no caregiver.”[ID 1]

“My crisis is determined by the fact that the team in which I work, has many difficulties in treating people with these problems [aggressiveness]. However, I felt that in this case there was the possibility to do something more. In my opinion, if we had to go beyond the protocols that our company requires, I think we could have had better success. So, I feel a bit guilty that I was not able to make others understand that there are alternative ways of dealing with such serious problems.”[ID 11]

3.1.3. Mediating with Relatives and/or the Caregiver

“One of the situations in which we often find ourselves is having a relative who pressurizes us and says for example: ‘let’s do everything we can’, and then, the elderly person who tells you, for example, I don’t want to dialyze anymore, so you find yourself having the elderly person who is there, maybe rather weakened [by illness], that you have to tie him up, sedate him to do the dialysis session, because the patient anyway is dangerous if he tears out the needles, in the end, he bleeds to death.”[ID 3]

“It can happen that the patient’s daughter arrives, and she pretends that daddy comes down with her to have coffee, while there was a very precise program with a physiotherapist, then the patient had to have at 10 o’clock antibiotic and sometimes everything is a bit difficult for her to understand.”[ID 4]

“I also do the video calls. I have this appointment with a lady and her daughter on dementia, so two pathologies together. Over the months she has clearly worsened and therefore her daughter, unfortunately, on the phone, is often in difficulty, she cries, etc. and any talk, in short, is useless.”[ID 10]

3.2. Care Provider Well-Being

3.2.1. Feelings Described during the MD Event

“I felt the weight on my shoulders of what was happening, and I was alone. I was alone and he was alone. I mean he was alone in the sense that he didn’t have anybody, and I was alone because I had so many other patients.”[ID 1]

“There is fear, there is also fear it is latent it is not perceived no...”[ID 5]

3.2.2. Feelings after the MD Event

“I felt I was doing the right thing [leaving some nursing activities behind, to be with the patient who was dying alone].”[ID 2]

“I felt, I had confirmation of the goodwill and correctness of the method.”[ID 5]

“It happened to me [within the group, the team] to be the only one who thought that it was necessary to think about it more, maybe postpone an exam [for the elderly person] or not do it.”[ID 6]

“Of failure. I felt failed unable to even make others listen to me, so a general inability. Almost, almost I questioned my professional skills because if I was not able to convince others of the usefulness of what they were proposing I told myself maybe I was not so convincing.”[ID 11]

3.2.3. Physical Consequences

“It changed my life drastically because it made me hypertensive at the age of 40.”[ID 5]

“So, the conclusion I’m aware of hurting myself and neglecting myself because anyway the translation of the fatigue of it all was obviously to make personal life choices that undoubtedly neglected my health.”[ID 5]

“I had headaches sometimes, but not so much because of a relationship with the host, but perhaps because of the demands of the organization that became excessive, let’s say, and therefore making people understand that they become excessive sometimes gives them a headache.”[ID 10]

3.2.4. Psychological Consequences

“When I came home, I was very distracted. I had to talk to my boyfriend and so on, but I was completely somewhere else. I wasn’t connecting, I was just distracted.”[ID 1]

“It causes me a sense of depression, crying, closure towards relationships with others.”[ID 11]

3.2.5. Residual Effects after Work

“At home, I bring back practically everything. Every time I arrive home and I am a blackboard. I always have to say everything, in fact, that’s what I can’t, that is why I cannot many times detach myself. I sometimes cannot switch off when I am at work, professionally.”[ID 7]

“I think that a person who is not confronted with these situations cannot in my opinion understand much.”[ID 1]

“With friends sometimes, we respect the sense of some things maybe without entering into the specific... because maybe, I find that they have to manage relatives.”[ID 3]

3.3. Decision Making

3.3.1. Group Morality

“Having a group moral, because one can have one’s own opinion. It’s one of the things that is most disorienting for the patient and the relatives, to see conflicting opinions, so I am one who believes anyway that in the end, you have to follow the will of the leader even if you do not agree, it is something that I think is right, this concept, so I do it.”[ID 3]

“If the team has decided that there was something to be done, I accept the result also because we bring something home.”[ID 6]

“Based on the assumption that my way of dealing with these patients who have issues, that also goes to affect the work of others.”[ID 12]

3.3.2. Team Engagement

“I have only spoken with colleagues because they have experienced the situation with me...”[ID 1]

“[The right choice] has always been a collective choice, it has always been a choice so in communion with colleagues there is no fundamental choice of direction that has not been the product of consensus.”[ID 5]

“Nobody ever asked me or let me express myself. [No one] felt it was necessary for me to express how I felt about that problem, they just [told me] what I should do or what I should not do.”[ID 11]

3.3.3. Self-Perceived Weakness

“[I missed specific] Skills”[ID 1]

“On the one hand, I felt maybe too much involvement in the situation i.e., that detachment that we should have at that time was maybe a bit lost.”[ID 2]

“Probably related a little bit to the emotional aspect.”[ID 10]

3.4. Protective Factors and Potential Solutions

3.4.1. Personal Characteristics

“A strong point [during the MD event] is tranquility. If you are calm and you face problems in a serene way the other party also faces it serenely with the person.”[ID 4]

“[My strength is] making others feel good so make them maybe smile and help them if they need it.”[ID 7]

“I lived great ethical moments in my extra-professional life, as I grew up in an environment strongly oriented to attributing an ethical sense to what happens; not only in a religious environment but also in social terms: I participated in many non-religious volunteering activities in which the question was: what is the sense of what we are doing?”[ID 5]

“When I have to make these decisions [whether or not to dialyze a patient who is now terminal] I think and rethink about it, I am religious I pray about it.”[ID 3]

“I never felt the need for psychological support. I do not say it with arrogance; but because my life is rich in social relationships.”[ID 5]

3.4.2. Professional Characteristics

“Definitely the experience [is a protecting factor]. If it had happened to me the day after I started work, I would have panicked.”[ID 12]

“[During the moral distress event] Neglect a little bit what is the real nursing work from the technical point of view.”[ID 2]

3.4.3. Support from the Leaders

“A bit of a breath of benefit, of that light benefit of trust that sort of unconditional trust that the institution as authoritative wants: scientific director, my mentor, my professor, my medical director conferred in me.”[ID 5]

“Good organization and good presence from the top.”[ID 7]

3.4.4. Psychological Support

“The nursing profession that has to have psychological support, because there are some jobs that ask for it, of course, and this is one thing that is a taboo in Italy. It is supposed if you say psychologist, it sounds as if you are crazy, but it is not like that.”[ID 4]

3.4.5. Relational Skills

“I’m a big believer in personalized care.”[ID 3]

“The key [to reduce MD] is the ability to include.”[ID 5]

“[To reduce MD] you have to learn the language of older children.”[ID 8]

3.4.6. Organizational Factors

“Increasing the number of operators can be one thing that can influence a lot on this thing [preventing moral distress events].”[ID 1]

“I am grateful to a structure that has always given me clarity of purpose.”[ID 5]

“But in my opinion, it is the first thing to give everyone the gradual responsibilities they deserve.”[ID 6]

3.5. Core Category

“[What can reduce moral distress] is communication and sharing daily.”[ID 5]

4. Discussion

4.1. Scarcity of Operators vs. Responsiveness

4.2. Hard Skills and Soft Skills

4.3. Inclusion vs. Isolation

4.4. External Pressure vs. Individual Balance

4.5. Sharing Daily vs. Accumulating Frustration

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jameton, A. Nursing Practice: The Ethical Issues; Englewood Cliffs: Bergen County, NJ, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg, M. Moral distress: A missing but relevant concept for ethics in social work. Can. Soc. Work Rev. 2009, 26, 139–151. [Google Scholar]

- Jaskela, S.; Guichon, J.; Page, S.A.; Mitchell, I. Social workers’ experience of Moral Distress. Can. Soc. Work Rev. 2018, 35, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Greenebaum, E. Attorneys’ problems in making ethical decisions. Indiana Law J. 1977, 52, 627. [Google Scholar]

- Gunzn, H.P.; Gunz, S.P. Client capture and the professional service firm. Am. Bus. Law J. 2008, 45, 685–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McRae, P. School leaders experiencing moral distress and exhaustion. Alberta Teach. Assoc. 2019, 100. Available online: https://www.teachers.ab.ca/News%20Room/ata%20magazine/Volume-100-2019-2020/Number-1/Pages/School-leaders-experiencing-moral-distress-and-exhaustion.aspx (accessed on 22 September 2021).

- Colnerud, G. Moral stress in teaching practice. Teach. Teach. Theory Pract. 2015, 21, 346–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gardner, W. Moral Distress in Teachers. Education Week. 2014. Available online: https://www.edweek.org/education/opinion-moral-distress-in-teachers/2014/10 (accessed on 22 September 2021).

- Váchová, M. Development of a tool for determining moral distress among teachers in basic schools. Pedagogika 2019, 69, 503–515. [Google Scholar]

- Molino, M.; Emanuel, F.; Zito, M.; Ghislieri, C.; Colombo, L.; Cortese, C.G. Inbound call centers and emotional dissonance in the job demands. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kälvemark Sporrong, S.; Arnetz, B.; Hansson, M.G.; Westerholm, P.; Höglund, A.T. Developing ethical competence in health care organizations. Nurs. Ethics 2007, 14, 825–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannetta, N.; Villa, G.; Pennestrì, F.; Sala, R.; Mordacci, R.; Manara, D.F. Ethical problems and moral distress in primary care: A scoping review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, J.M. Moral distress in nursing practice: Experience and effect. Nurs. Forum 1987, 23, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, A.M.F. Beyond burnout: Looking deeply into physician distress. Can. J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 55, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mudallal, R.H.; Othman, W.M.; Al Hassan, N.F. Nurses’ burnout: The influence of leader empowering behaviors, work conditions, and demographic traits. INQUIRY J. Health Care Organ. Provis. Financ. 2017, 1, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wagner, C. Moral distress as a contributor to nurse burnout. Am. J. Nurs. 2015, 115, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Austin, W. Contemporary healthcare practice and the risk of moral distress. Healthc Manage Forum. 2016, 29, 131–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freudenberger, H.J. Staff burn-out. J. Soc. Issues 1974, 90, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Nurses Association. Exploring Moral Resilience toward a Culture of Ethical Practice. A Call to Action Report. 2017. Available online: https://www.nursingworld.org/~4907b6/globalassets/docs/ana/ana-call-to-action--exploring-moral-resilience-final.pdf (accessed on 22 September 2021).

- Perni, S.; Pollack, L.R.; Gonzalez, W.C.; Dzeng, E.; Baldwin, M.R. Moral distress and burnout in caring for older adults during medical school training. BMC Med. Educ. 2020, 20, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpenter, C. Moral distress in physical therapy practice. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2010, 26, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodger, D.; Blackshaw, B.; Young, A. Moral distress in healthcare assistants: A discussion with recommendations. Nurs. Ethics. 2019, 26, 2306–2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deady, R.; McCarthy, J. A study of the situations, features, and coping mechanisms experienced by Irish psychiatric nurses experiencing moral distress. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2010, 46, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harrowing, J.N.; Mill, J. Moral distress among Ugandan nurses providing HIV care: A critical ethnography. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2010, 47, 723–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Corley, M.C.; Minick, P.; Elswick, R.K.; Jacobs, M. Nurse moral distress and ethical work environment. Nurs. Ethics 2005, 12, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, B. Preserving moral integrity: A follow-up study with new graduate nurses. J. Adv. Nurs. 1998, 28, 1134–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson Foundation’s Wingspread Center. A Gold Bond to Restore Joy in Nursing: A Collaborative Exchange of Ideas to Address Burnout. 2017. Available online: https://ajnoffthecharts.com/wpcontent/uploads/2017/04/NursesReport_Burnout_Final.pdf (accessed on 22 September 2021).

- Dyrbye, L.; Shanafelt, T. A narrative review on burnout experienced by medical students and residents. Med. Educ. 2016, 50, 132–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, D.; Villa, G.; Togni, S.; Bonetti, L.; Destrebecq, A.; Terzoni, S. How to protect older adults with comorbidities during phase 2 of the COVID-19 pandemic: Nurses’ contributions. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 2020, 46, 7–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manara, D.F. Times and spaces of care: Home, hospital. Prof. Inferm. 2006, 59, 131–141. [Google Scholar]

- Boddington, P.; Featherstone, K. The canary in the coal mine: Continence care for people with dementia in acute hospital wards as a crisis of dehumanization. Bioethics 2018, 32, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rushton, C.; Nilsson, A.; Edvardsson, D. Reconciling concepts of time and person-centred care of the older person with cognitive impairment in the acute care setting. Nurs. Philos. 2016, 17, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saarnio, R.; Sarvimäki, A.; Laukkala, H.; Isola, A. Stress of conscience among staff caring for older persons in Finland. Nurs. Ethics 2012, 19, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Union Eurostat. Ageing Europe; Office of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2019.

- De Brasi, E.L.; Giannetta, N.; Ercolani, S.; Gandini, E.L.M.; Moranda, D.; Villa, G.; Manara, D.F. Nurses’ moral distress in end-of-life care: A qualitative study. Nurs. Ethics 2020, 28, 614–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannetta, N.; Villa, G.; Pennestrì, F.; Sala, R.; Mordacci, R.; Manara, D.F. Instruments to assess moral distress among healthcare workers: A systematic review of measurement properties. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2020, 111, 103767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennestrì, F. Dalla cura al prendersi cura: La riforma sociosanitaria lombarda fra equità, universalismo e sostenibilità. Polit. Sanit. 2017, 18, 113–127. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J.M.; Strauss, A. Basics of Qualitative Research, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Rorty, R. Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lingard, L.; Albert, M.; Levinson, W. Grounded theory, mixed methods, and action research. BMJ 2008, 337, a567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, C.; Astin, F. Grounded theory: What makes a grounded theory study? Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2021, 20, 285–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandelowski, M. Sample size in qualitative research. Res. Nurs. Health 1995, 18, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarozzi, M. Che Cos’ è la Grounded Theory Roma; Carocci: Rome, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Archibald, M.M.; Ambagtsheer, R.C.; Casey, M.G.; Lawless, M. using zoom videoconferencing for qualitative data collection: Perceptions and experiences of researchers and participants. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2019, 18, 160940691987459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Institute of Medicine (U.S.). Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. In To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health, System; Kohn, L., Corrigan, J., Donaldson, M., Eds.; Institute of Medicine: Washington, DC, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Elst, E.; de Casterlé, B.D.; Gastmans, C. Elderly patients’ and residents’ perceptions of ‘the good nurse’: A literature review. J. Med. Ethics 2012, 38, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcomini, I.; Destrebecq, A.; Rosa, D.; Terzoni, S. Self-reported skills for ensuring patient safety and quality of care among Italian nursing students: A descriptive cross-sectional study. Int. J. Health Promot. Educ. 2021, 21, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterkin, A.; Skorzewska, A. Health Humanities in Postgraduate Medical Education; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ter Meulen, R.H.J. The lost voice: How libertarianism and consumerism obliterate the need for a relational ethics in the national health care service. Christ. Bioeth. 2008, 14, 78–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludvigsen, B. Market Thinking and Home Nursing. Perspectives on New Socialities in Healthcare in Denmark. In Emerging Socialities in 21st Century Health Care; Hadolt, B., Hardon, A., Eds.; Amsterdam University Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bolmsjö, I.Å.; Sandman, L.; Andersson, E. Everyday ethics in the care of elderly people. Nurs. Ethics 2006, 13, 249–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chivers, S.C.; Kriebernegg, U. Care Home Stories: Aging, Disability, and Long-Term Residential Care; Transcript Verlag: Bielefeld, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Eddy, K.; Jordan, Z.; Stephenson, M. Health professionals’ experience of teamwork education in acute hospital settings. JBI Database Syst. Rev. Implement. Rep. 2016, 14, 96–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salas, E.; Diaz Granados, D.; Weaver, S.J.; King, H. Does team training work? Principles for health care. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2008, 15, 1002–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brodtkorb, K.; Skisland, A.V.-S.; Slettebø, Å.; Skaar, R. Ethical challenges in care for older patients who resist help. Nurs. Ethics 2015, 22, 631–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriquez, J. Attributions of agency and the construction of moral order: Dementia, death, and dignity in nursing-home care. Soc. Psychol. Q. 2009, 72, 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Manara, D.F.; Villa, G.; Moranda, D. In search of salience: Phenomenological analysis of moral distress. Nurs. Philos. 2014, 15, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manara, D.F.; Giannetta, N.; Villa, G. Violence versus gratitude: Courses of recognition in caring situations. Nurs. Philos. 2020, 21, e12312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldh, A.C.; van der Zijpp, T.; McMullan, C.; McCormack, B.; Seers, K.; Rycroft-Malone, J. ‘I have the world’s best job’—Staff experience of the advantages of caring for older people. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2016, 30, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barello, S.; Palamenghi, L.; Graffigna, G. Burnout and somatic symptoms among frontline healthcare professionals at the peak of the Italian COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 290, 113129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmoirago-Blotcher, E.; Fitchett, G.; Leung, K.; Volturo, G.; Boudreaux, E.; Crawford, S.; Ockene, I.; Curlin, F. An exploration of the role of religion/spirituality in the promotion of physicians’ wellbeing in Emergency Medicine. Prev. Med. Rep. 2016, 3, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vaclavik, E.; Staffileno, B.; Carlson, E. Moral distress: Using mindfulness-based stress reduction interventions to decrease nurse perceptions of distress. Clin. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2018, 22, 326–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazzari, T.; Terzoni, S.; Destrebecq, A.; Meani, L.; Bonetti, L.; Ferrara, P. Moral distress in correctional nurses: A national survey. Nurs. Ethics 2020, 27, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, D.F. Mens sana in corpore sano: Student well-being and the development of resilience. Med. Educ. 2016, 50, 20–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovová, M.; Sovová, E.; Nakládalová, M.; Pokorná, T.; Štégnerová, L.; Masný, O.; Moravcová, K.; Štěpánek, L. Are our nurses healthy? Cardiorespiratory fitness in a very exhausting profession. Cent. Eur. J. Public Health 2020, 28, S53–S56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theorell, T.; Karasek, R.A. Current issues relating to psychosocial job strain and cardiovascular disease research. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 1996, 1, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuman, J.L.; Mau, L.-W.; Virani, S.; Denzen, E.M.; Boyle, D.A.; Boyle, N.J.; Dabney, J.; de Kesellofthus, A.; Kalbacker, M.; Khan, T.; et al. Burnout, moral distress, work–life balance, and career satisfaction among hematopoietic cell transplantation professionals. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2018, 24, 849–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sokolowski, M. Sex, dementia and the nursing home: Ethical issues for reflection. J. Ethics Ment. Heal. 2012, 7, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Levinson, W. Physician-patient communication. The relationship with malpractice claims among primary care physicians and surgeons. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1997, 277, 553–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charon, R. Narrative Medicine: Honoring the Stories of Illness; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Cingel, M. Compassion in care: A qualitative study of older people with a chronic disease and nurses. Nurs. Ethics 2011, 18, 672–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camera di Commercio Industria Artigianato Agricoltura di Torino. Counseling per gli Operatori Della Salute; API Formazione: Torino, Italy, 2010; Available online: https://www.yumpu.com/it/document/view/16108011/counseling-per-gli-operatori-della-salute-api-formazione (accessed on 22 September 2021).

- Gobbi, P.; Castoldi, M.G.; Alagna, R.A.; Brunoldi, A.; Pari, C.; Gallo, A.; Magri, M.; Marioni, L.; Muttillo, G.; Passoni, C.; et al. Validity of the Code of Ethics for everyday nursing practice. Nurs. Ethics 2018, 25, 906–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polit, D.; Beck, C. Nursing Research, 11th ed.; Wolters Kluwer: Alphen aan den Rijn, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

| Characteristis | Sample |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 8 |

| Male | 5 |

| Age | |

| 18–34 | 5 |

| 35–49 | 2 |

| 50–69 | 6 |

| Education | |

| High School | 1 |

| Bachelor | 8 |

| Degree | 4 |

| Marital Status | |

| Married/living together | 7 |

| Single | 4 |

| Separated/divorced | 1 |

| Missing | 1 |

| Children | |

| No children | 7 |

| 1 | 2 |

| 2 | 2 |

| Missing | 2 |

| Work Setting | |

| Hospital | 6 |

| Nursing Home | 7 |

| Type of contracts | |

| Full Time | 10 |

| Part Time | 2 |

| Missing | 1 |

| Type of work | |

| Certified Nursing Assistants | 2 |

| Professional Educator | 1 |

| Physiotherapist | 1 |

| Nurse | 5 |

| Physician | 3 |

| Psychologist | 1 |

| Years of work experience (average) | 13.5 |

| Years of work experience with elderly people (average) | 11.16 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Villa, G.; Pennestrì, F.; Rosa, D.; Giannetta, N.; Sala, R.; Mordacci, R.; Manara, D.F. Moral Distress in Community and Hospital Settings for the Care of Elderly People. A Grounded Theory Qualitative Study. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1307. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9101307

Villa G, Pennestrì F, Rosa D, Giannetta N, Sala R, Mordacci R, Manara DF. Moral Distress in Community and Hospital Settings for the Care of Elderly People. A Grounded Theory Qualitative Study. Healthcare. 2021; 9(10):1307. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9101307

Chicago/Turabian StyleVilla, Giulia, Federico Pennestrì, Debora Rosa, Noemi Giannetta, Roberta Sala, Roberto Mordacci, and Duilio Fiorenzo Manara. 2021. "Moral Distress in Community and Hospital Settings for the Care of Elderly People. A Grounded Theory Qualitative Study" Healthcare 9, no. 10: 1307. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9101307

APA StyleVilla, G., Pennestrì, F., Rosa, D., Giannetta, N., Sala, R., Mordacci, R., & Manara, D. F. (2021). Moral Distress in Community and Hospital Settings for the Care of Elderly People. A Grounded Theory Qualitative Study. Healthcare, 9(10), 1307. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9101307