Exploring Health Information Sharing Behavior of Chinese Elderly Adults on WeChat

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background Literature

2.1. Social Media and Information Sharing

2.2. Health Information Sharing Behavior

- Q1: What are the specific behaviors of the elderly in China to share health information?

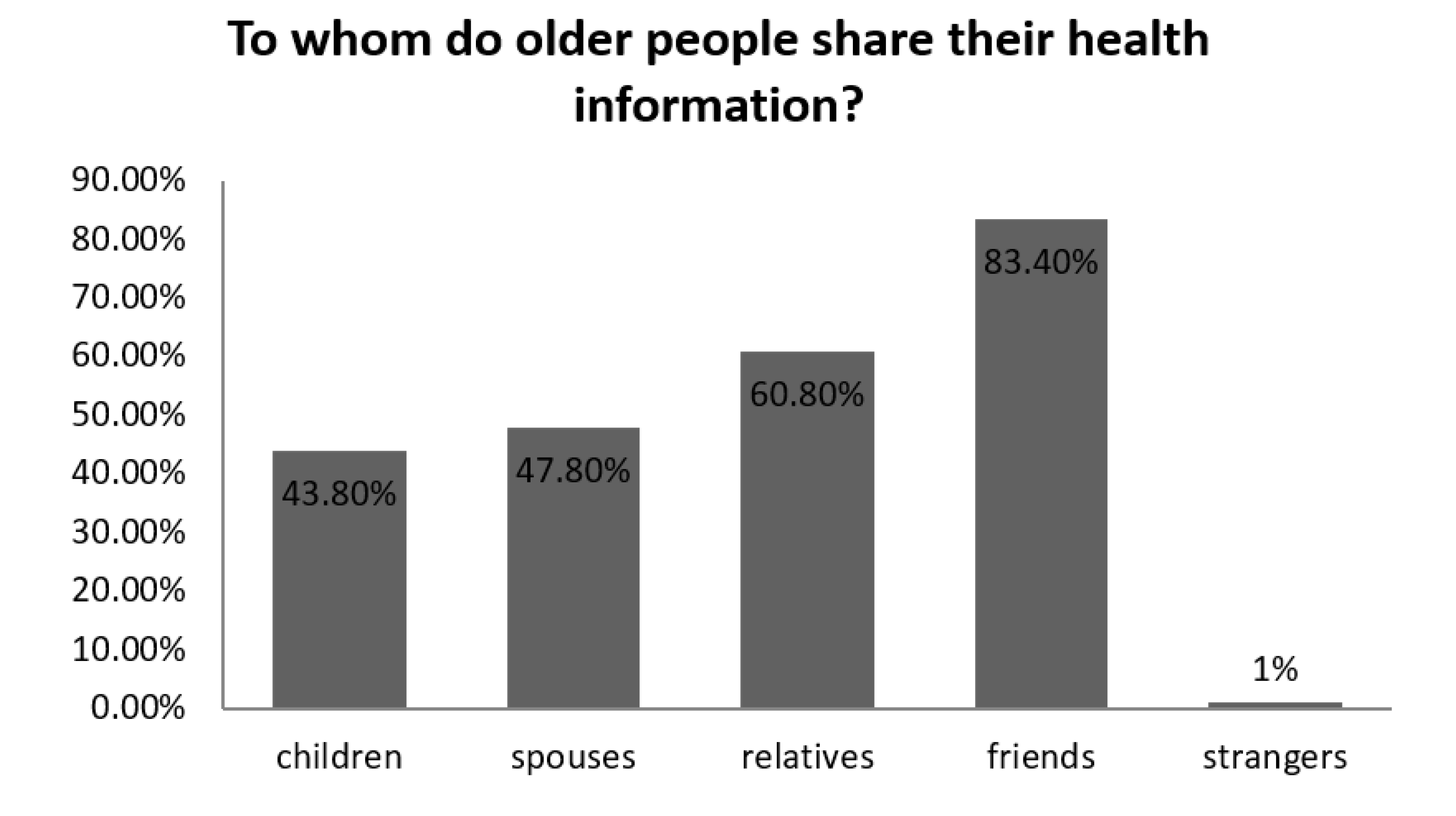

- Q2: To whom do Chinese elderly adults share their health information?

2.3. Self-Efficacy and Health Information Sharing Behavior

2.4. Media Credibility and Health Information Sharing Behavior

2.5. Social Orientation and Health Information Sharing Behavior

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

6.2. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dhir, A.; Torsheim, T. Age and gender differences in photo tagging gratifications. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 63, 630–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhir, A.; Tsai, C.C. Understanding the relationship between intensity and gratifications of Facebook use among adolescents and young adults. Telemat. Inform. 2017, 34, 350–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. Am. Psychol. 1982, 37, 122–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, J.L., Jr. Factors of source credibility. Q. J. Speech 1968, 54, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aristotle. The Rhetoric of Aristotle; Roberts, W.R., Ed.; Modern Library: New York, NY, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Hovland, C.I.; Janis, I.L.; Kelley, H.H. Communication and Persuasion; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Kreuter, M.W.; Clure, S.M.M. The Role of Culture in Health Communication. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2004, 25, 439–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filieri, R.; Chen, W.; Dey, B.L. The importance of enhancing, maintaining and saving face in smartphone repurchase intentions of Chinese early adopters. Inf. Technol. People 2017, 30, 629–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhir, A.; Khalil, A.; Lonka, K.; Tsai, C.C. Do educational affordances and gratifications drive intensive Facebook use among adolescents? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 68, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhir, A.; Kaur, P.; Lonka, K.; Tsai, C.C. Do psychosocial attributes of well-being drive intensive Facebook use? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 68, 520–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhir, A.; Kaur, P.; Rajala, R. Why do young people tag photos on social networking sites? Explaining user intentions. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 38, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhir, A.; Chen, G.M.; Chen, S. Why do we tag photographs on Facebook? Proposing a new gratifications scale. New Media Soc. 2017, 19, 502–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.; Dhir, A.; Nieminen, M. Uses and gratifications of digital photo sharing on Facebook. Telemat. Inform. 2016, 33, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zigkolis, C.; Papadopoulos, S.; Filippou, G.; Kom-patsiaris, Y.; Vakali, A. Collaborative event annotation in tagged photo collections. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2014, 70, 89–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayebi, S.; Manesh, S.; Khalili, M.; Sadi-Nezhad, S. The role of information systems in communication through social media. Int. J. Data Netw. Sci. 2019, 3, 245–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Social Life of Health Information. Pew Internet & American Life Project. Available online: http://www.pewresearch.org/facttank/2014/01/15/the-social-life-of-health-information/ (accessed on 4 July 2017).

- Medlock, S.; Eslami, S.; Askari, M.; Arts, D.L.; Sent, D.; De Rooij, S.E.; Abu-Hanna, A. Health information–seeking behavior of seniors who use the internet: A survey. J. Med Internet Res. 2015, 17, e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, L.M.S.; Bell, R.A. Online health information seeking. J. Aging Health 2012, 24, 525–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wen, D.; Liang, J.; Lei, J. How the public uses social media wechat to obtain health information in china: A survey study. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2017, 17, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Deng, S. The influence of information technology on health information behavior—A systematic review. J. Inf. Resour. Manag. 2016, 6, 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, R.; Sambamurthy, V.; Stair, R.M. The evolving relationship between general and specific computer self-efficacy—An empirical assessment. Inf. Syst. Res. 2000, 11, 418–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strecher, V.J.; Evoy, M.; De Vellis, B.; Becker, M.H.; Rosenstock, I.M. The role of self-efficacy in achieving health behavior change. Health Educ. Q. 1986, 13, 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, G.W.; Kim, Y.G. Breaking the myths of rewards: An exploratory study of attitudes about knowledge sharing. Inf. Resour. Manag. J. 2002, 15, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, K.; Zhou, J.; Wang, Y. Personal characteristics, information sharing attitude and sharing behavior on social network—A study based on renren. Mod. Intell. 2014, 34, 159–166. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M. The research of human individual’s conformity behavior in emergency situations. Libr. Hi Tech. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crook, B.; Stephens, K.K.; Pastorek, A.E.; Mackert, M.; Donovan, E.E. Sharing health information and influencing behavioral intentions: The role of health literacy, information overload, and the internet in the diffusion of healthy heart information. Health Commun. 2016, 31, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The 45th China Statistical Report on Internet Development. Available online: http://www.cnnic.net.cn/hlwfzyj/hlwxzbg/hlwtjbg/202004/P020200428596599037028 (accessed on 21 June 2020).

- Shah, A.A.; Ravana, S.D.; Hamid, S.; Ismail, M.A. Web credibility assessment: Affecting factors and assessment techniques. Inf. Res. 2015, 20, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Gwizdka, J.; Trace, C.B. Consumer evaluation of the quality of online health information: Systematic literature review of relevant criteria and indicators. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e12522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiousis, S. Public trust or mistrust? Perceptions of media credibility in the information age. Mass Commun. Soc. 2001, 4, 381–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagin, A.J.; Metzger, M.J. The credibility of volunteered geographic information. Geo. J. 2008, 72, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Yan, Y. Media credibility research: Origin, development, opportunity, and challenges. Commun. Soc. 2015, 33, 255–297. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.X.; Zeng, H.M. A study on the correlation between network use, network dependence and network information reliability. J. Hubei Univ. 2007, 34, 111–115. [Google Scholar]

- Arora, N.K.; Hesse, B.W.; Rimer, B.K.; Viswanath, K.; Clayman, M.L.; Croyle, R.T. Frustrated and confused: The American public rates its cancer-related information-seeking experiences. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2008, 23, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feufel, M.A.; Stahl, S.F. What do web-use skill differences imply for online health information searches? J. Med. Internet Res. 2012, 14, e87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Car, J.; Lang, B.; Colledge, A.; Ung, C.; Majeed, A. Interventions for enhancing consumers’ online health literacy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2011, 2011, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yun, E.K.; Park, H.A. Consumers’ disease information–seeking behaviour on the internet in korea. J. Clin. Nurs. 2010, 19, 2860–2868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metzger, M.J.; Flanagin, A.J. Using web 2.0 technologies to enhance evidence-based medical information. J. Health Commun. 2011, 16, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y. Correlates of consumer trust in online health information: Findings from the health information national trends survey. J. Health Commun. 2011, 16, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Shim, M. The role of provider–patient communication and trust in online sources in Internet use for health-related activities. J. Health Commun. 2010, 15 (Suppl. 3), 186–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huh, J.; De Lorme, D.E.; Reid, L.N. Factors affecting trust in on-line prescription drug information and impact of trust on behavior following exposure to DTC advertising. J. Health Commun. 2005, 10, 711–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Sharma, S.K. Self-disclosure at social networking sites: An exploration through relational capitals. Inf. Syst. Front. 2013, 15, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, N.; Nam, K.; Koo, C. Examining Information Sharing in Social Networking Communities; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; Volume 33, pp. 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. Trust in health information websites: A systematic literature review on the antecedents of trust. Health Inform. J. 2016, 22, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Dong, X. Research on the influence of consuming information content characteristics on information sharing behavior in virtual communities. J. Intell. 2014, 1, 201–206. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Wang, X.; Li, S.; Zhang, L. Research on influencing factors of WeChat usage behavior of elderly users from the perspective of information ecology. Libr. Inf. Work. 2017, 15, 25–33. [Google Scholar]

- Shea, M.; Yeh, C. Asian American students’cultural values, stigma, and relational self-construal: Correlates of attitudes toward professional help seeking. J. Ment. Health Couns. 2008, 30, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M. The Impact of Expatriates’ Cross-Cultural Adjustment on Work Stress and Job Involvement in the High-Tech Industry. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Interim Measures of the State Council on the Retirement and Resignation of Workers. Available online: https://www.chashebao.com/shebaotiaoli/2513 (accessed on 4 July 2017).

- Wong, C.K.; Yeung, D.Y.; Ho, H.C.; Tse, K.-P.; Lam, C.-Y. Chinese older adults’ Internet use for health information. J. Appl. Gerontol. Off. J. South. Gerontol. Soc. 2014, 33, 316–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Sandner, J. Like a “Frog in a well”? An ethnographic study of Chinese rural women’s social media practices through the WeChat platform. Chin. J. Commun. 2019, 12, 324–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constitution of the People’s Republic of China. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/govweb/test/2005-06/14/content_6310_4 (accessed on 29 July 2017).

- Metzger, M.J.; Flanagin, A.J.; Zwarun, L. College student Web use, perceptions of information credibility, and verification behavior. Comput. Educ. 2003, 41, 271–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhir, A.; Kaur, P.; Lonka, K.; Nieminen, M. Why do adolescents untag photos on Facebook? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 55, 1106–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.G.; Liu, X. The basis of trust: A rational explanation. Sociol. Res. 2002, 3, 25–41. [Google Scholar]

- Bilchik, T.R.; Heyman, S. Skeletal scintigraphy of pseudo-osteomyelitis in Gaucher’s disease. Two case reports and a review of the literature. Clin. Nucl. Med. 1992, 17, 279–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Huang, C.; Ye, M.; Ou, R.; Yuan, Y. Empirical study on influence factors on user’s health information diffusion behavior on weibo. J. Libr. Sci. 2017, 21, 83–93. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, P.; Dhir, A.; Rajala, R.; Dwivedi, Y. Why people use online social media brand communities: A consumption value theory perspective. Online Inf. Rev. 2018, 42, 205–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhir, A.; Kaur, P.; Chen, S.; Lonka, K. Understanding online regret experience in Facebook use–Effects of brand participation, accessibility & problematic use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 59, 420–430. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, P.; Dhir, A.; Rajala, R. Assessing flow experience in social networking site based brand communities. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 64, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Zhan, Q.D. Research on the Motivation of Postgraduate Group Information Sharing. Libr. Inf. Sci. 2012, 2, 81–86. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, P.; Dhir, A.; Chen, S.; Rajala, R. Flow in context: Development and validation of the flow experience instrument for social networking. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 59, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, X.W. Relationships and Chinese Society; China Social Science Press: Beijing, China, 2012; pp. 104–106. [Google Scholar]

- Guess, A.; Nagler, J.; Tucker, J. Less than you think: Prevalence and predictors of fake news dissemination on Facebook. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaau4586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carstensen, L.L.; Fung, H.H.; Charles, S.T. Socioemotional selectivity theory and the regulation of emotion in the second half of life. Motiv. Emot. 2003, 27, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Lu, Y. Research on Knowledge Sharing Behavior of Virtual Community Users Based on Social Impact Theory. Res. Dev. Manag. 2009, 21, 78–83. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.H.; Ji, E.J.; Yun, O.J. Health concern, health information orientation, e-health literacy and health behavior in aged women: Focused on 60–70s. J. Converg. Inf. Technol. 2019, 9, 39–47. [Google Scholar]

- Sotoudeh, R.F.; Taghizadeh, A.; Heidari, Z.; Keshvari, M. Investigating the Relationship between Media Literacy and Health Literacy in Iranian Adolescents, Isfahan, Iran. Int. J. Pediatrics 2020, 8, 11321–11329. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, C.-W.; Min, C.; Wang, C.-C. Analyzing the trend of O2O commerce by bilingual text mining on social media. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 101, 474–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Range | M(SD) | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years | 60–75 | ||

| Female (vs. male) | 62.8% | ||

| Health status (with chronic disease) | 65.7% | ||

| Education | 1–5 (from illiteracy to junior college or above) | 5.39 (0.77) | |

| Personal monthly income | 1–6 (from¥500–1000 to¥6500 yuan or more) | 4.9 (1.08) | |

| online health information experience | 1–4 (from often to never) | 2.86 (0.68) | |

| Health information credibility | 1–4 (from bad to good) | 1.98 (0.43) | |

| Relationship orientation | 1–4 (from Very much in line to not at all) | 2.10 (0.48) | |

| Authority orientation | 1–4 (from Very much in line to not at all) | 1.87 (0.49) | |

| Family orientation | 1–4 (from Very much in line to not at all) | 1.61 (0.47) | |

| Health information sharing | 1–4 (from often to never) | 3.07 (0.54) |

| Health Information Sharing | More Often (%) | Sometime (%) | Occasionally (%) | Never (%) | M (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forward health information | 16.7 | 50.3 | 19.9 | 13.1 | 2.36 (0.89) |

| inquire health information | 2.1 | 38.7 | 31.8 | 27.4 | 3.14 (0.69) |

| reply health information | 4.5 | 34.7 | 29.5 | 31.3 | 3.15 (0.77) |

| Post health information | 3 | 33.6 | 32.1 | 31.3 | 3.24 (0.70) |

| Variable | SE (Standard Error) | β (Beta) | t (t Test Value) | Sig. (Significance) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| constant | 0.209 | 7.207 | 0.000 *** | |

| Gender (female) | 0.057 | 0.102 | 1.999 | 0.046 * |

| Health status (with chronic disease) | 0.051 | 0.024 | 0.497 | 0.620 |

| Personal monthly income | 0.026 | 0.018 | 0.349 | 0.727 |

| Health information credibility | 0.026 | −0.009 | −0.190 | 0.849 |

| online health information experience | 0.040 | 0.417 | 8.354 | 0.000 *** |

| Authority orientation | 0.065 | 0.119 | 2.037 | 0.042 * |

| Family orientation | 0.062 | 0.004 | 0.083 | 0.934 |

| Relationship orientation | 0.063 | 0.109 | 1.926 | 0.049 * |

| Hypothesis | Path | β | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | online health information experience→Health information sharing | 0.417 | p < 0.001 |

| H2 | Health information credibility→Health information sharing | −0.009 | n.s |

| H3-1 | relationship orientation→Health information sharing | 0.109 | p < 0.05 |

| H3-2 | authority orientation→Health information sharing | 0.119 | n.s |

| H3-3 | family orientation→Health information sharing | 0.004 | p < 0.05 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, W.; Zhuang, X.; Shao, P. Exploring Health Information Sharing Behavior of Chinese Elderly Adults on WeChat. Healthcare 2020, 8, 207. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8030207

Wang W, Zhuang X, Shao P. Exploring Health Information Sharing Behavior of Chinese Elderly Adults on WeChat. Healthcare. 2020; 8(3):207. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8030207

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Wei, Xin Zhuang, and Peng Shao. 2020. "Exploring Health Information Sharing Behavior of Chinese Elderly Adults on WeChat" Healthcare 8, no. 3: 207. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8030207

APA StyleWang, W., Zhuang, X., & Shao, P. (2020). Exploring Health Information Sharing Behavior of Chinese Elderly Adults on WeChat. Healthcare, 8(3), 207. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8030207