The Quality of Life among Men Receiving Active Surveillance for Prostate Cancer: An Integrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Prostate Cancer

1.2. Active Surveillance

Active Surveillance among African Americans

1.3. Quality of Life

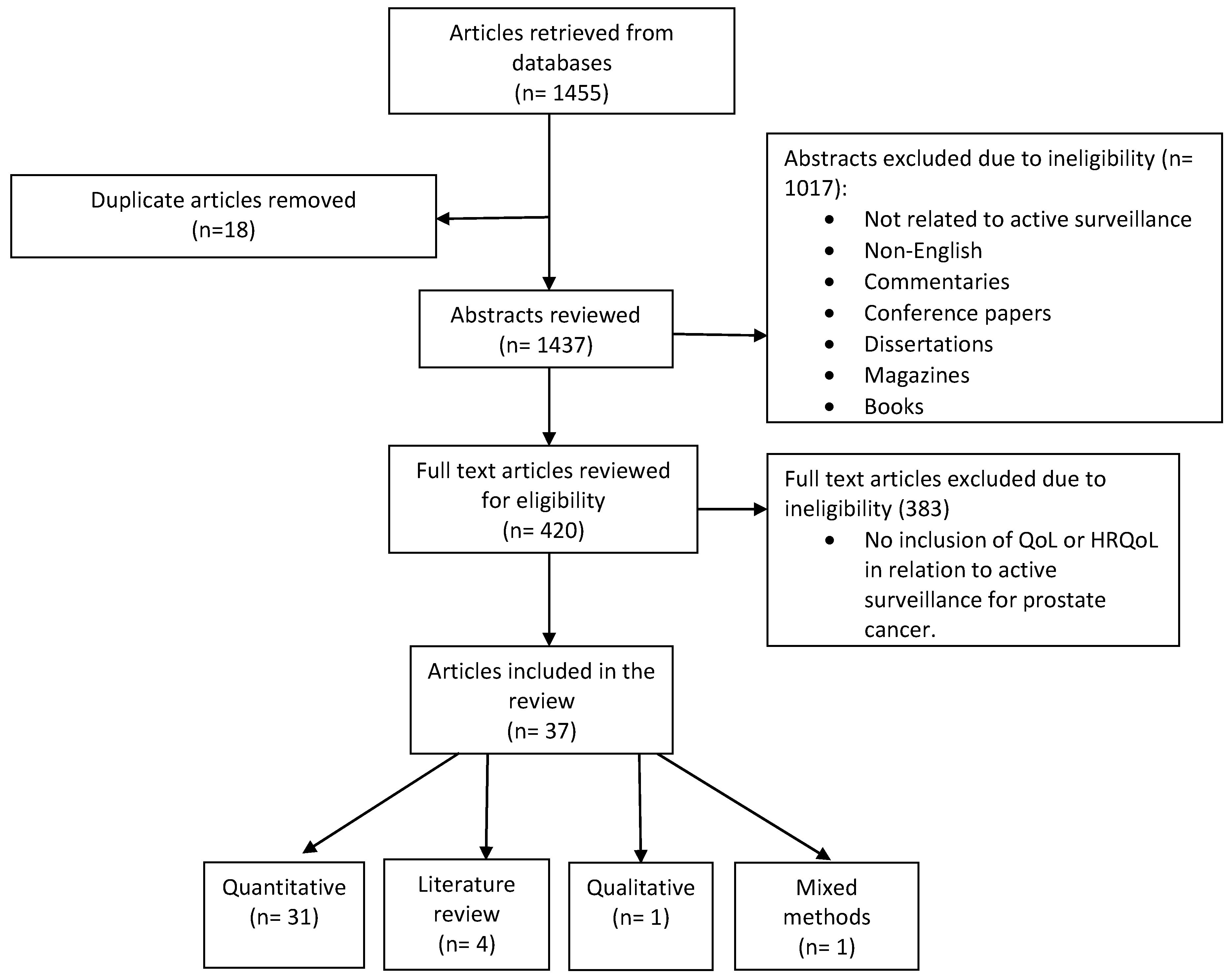

2. Methods

2.1. Integrative Review Methodology

2.2. Search of the Databases

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sexual, Bladder, and Bowel Function and Anxiety and Depression Factors of QoL among Active Surveillance and Other Forms of Treatments

3.1.1. Erectile and Sexual Function Factors of QoL among Active Surveillance and Other Forms of Treatments

3.1.2. Bladder and Bowel Factors of QoL among Active Surveillance and Other Forms of Treatment

3.1.3. Combination of Physiological and Psychological Factors of QoL among Active Surveillance and Other Forms of Treatment

3.2. Anxiety and Depression Factors for QoL among Active Surveillance Treatment

3.2.1. Anxiety and Depression Factors for QoL among Men Only Receiving Active Surveillance

3.2.2. Anxiety and Depression Factors for QoL among Active Surveillance and Other Forms of Treatments

4. Discussion

5. Clinical Implications

6. Strengths and Limitations

7. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Daniyal, M.; Siddiqui, Z.A.; Akram, M.; Asir, H.M.; Sultana, S.; Khan, A. Epidemiology, etiology, diagnosis and treatment of prostate cancer. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2014, 15, 9575–9578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Cancer Society. American Cancer Society Medical and Content Team Survival rates for prostate cancer. American Cancer Society Statistics Center. 2016. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/prostate-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/survival-rates.html (accessed on 6 August 2017).

- Albertsen, P.C. When is active surveillance the appropriate treatment for prostate cancer? Acta Oncol. 2010, 50, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bangma, C.H.; Bul, M.; van der Kwast, T.H.; Pickels, T.; Korfage, I.J.; Hoeks, C.M.; Steyerberg, E.W.; Jenster, G.; Kattan, M.W.; Bellardita, L.; et al. Active surveillance for low-risk prostate cancer. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2013, 85, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dall′Era, M.A.; Albertsen, P.C.; Bangma, C.; Carroll, P.R.; Carter, H.B.; Cooperberg, M.R.; Freedland, S.J.; Klotz, L.H.; Parker, C.; Soloway, M.S. Active surveillance for prostate cancer: A systematic review of the literature. Eur. Urol. 2012, 62, 976–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeldres, C.; Cullen, J.; Hurwitz, L.M.; Wolff, E.M.; Levie, K.E.; Odem-Davis, K.; Johnston, R.B.; Pham, K.N.; Rosner, I.L.; Brand, T.C.; et al. Prospective quality-of-life outcomes for low-risk prostate cancer: Active surveillance versus radical prostatectomy. Cancer 2015, 121, 2465–2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanda, M.G.; Dunn, R.L.; Michalski, J.; Sandler, H.M.; Northouse, L.; Hembroff, L.; Lin, X.; Greenfield, T.K.; Litwin, M.S.; Saigal, C.S.; et al. Quality of life and satisfaction with outcome among prostate-cancer survivors. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 358, 1250–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, H.B. Active surveillance for prostate cancer: An underutilized opportunity for reducing harm. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. Monogr. 2012, 175, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drost, F.H.; Rannikko, A.; Valdagni, R.; Pickles, T.; Kakehi, Y.; Remmers, S.; van der Poel, H.G.; Bangma, C.H.; Roobol, M.J. Can active surveillance really reduce the harms of overdiagnosing prostate cancer? A reflection of real life clinical practice in the PRIAS study. Transl. Androl. Urol. 2018, 1, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tosoian, J.J.; Carter, H.B.; Lepor, A.; Loeb, S. Active surveillance for prostate cancer: Current evidence and contemporary state of practice. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2016, 13, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klotz, L. Active surveillance for low-risk prostate cancer. Curr. Opin. Urol. 2017, 27, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otero, J.R.; Gómez, B.G.; Ojeda, J.M.; Rodríguez-Antol, A.; Vilaseca, A.; Carlsson, S.V.; Touije, K.A. Active surveillance for prostate cancer. Int. J. Urol. 2016, 23, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics. CA: A Cancer J. Clin. 2016, 66, 7–30. [Google Scholar]

- Klotz, L. Active surveillance for prostate cancer: A review. Curr. Urol. Rep. 2010, 11, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davison, B.J.; Oliffe, J.L.; Pickles, T.; Mroz, L. Factors influencing men undertaking active surveillance for the management of low-risk prostate cancer. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2009, 36, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, P.A.; Davis, J.W.; Latini, D.M.; Baum, G.; Wang, X.; Ward, J.F.; Kuban, D.; Frank, S.J.; Lee, A.K.; Logothetis, C.J. Relationship between illness uncertainty, anxiety, fear of progression and quality of life in men with favorable-risk prostate cancer undergoing active surveillance. Br. J. Urol. Int. 2016, 117, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganz, P.A. National Institutes of Health State-of-the-Science Conference: Role of active surveillance in the management of men with localized prostate cancer. Ann. Intern Med. 2012, 156, 591–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morash, C. Active surveillance for the management of localized prostate cancer: Guideline recommendations. Can. Urol. Assoc. J. 2015, 9, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosoian, J.J.; Loeb, S.; Epstein, J.I.; Turkbey, B.; Chokye, P.; Schaeffer, E.M. Active surveillance of prostate cancer: Use, outcomes, imaging, and diagnostic tools. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 2016, 35, e235–e245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooperberg, M.R.; Carroll, P.R.; Klotz, L. Active surveillance for prostate cancer: Progress and promise. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 29, 3669–3676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooperberg, M.R.; Carroll, P.R. Trends in management for patients with localized prostate cancer, 1990-2013. J Am. Med. Assoc. 2015, 314, 80–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooperberg, M.; Fang, R.; Wolf, J.S.; Hubbard, T.; Pendharkar, S.; Gupte, S.; Ross, K.; Nolin, M.; Schlossberg, S.; Clemens, J.Q. The current management of prostate cancer in the United States: Data from the AQUA registry. J. Urol. 2017, 197, e911–e912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venderbos, L.; Aluwini, S.; Roobol, M.; Bokhorst, L.P.; Oomens, E.H.; Bangma, C.H.; Korfage, I.J. Long-term follow-up after active surveillance or curative treatment: Quality-of-life outcomes of men with low-risk prostate cancer. Qual. Life Res. 2017, 26, 1635–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haymart, M.R.; Miller, D.C.; Hawley, S.T. Active surveillance for low-risk cancers—A viable solution to overtreatment? N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 203–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavlarides, A.M.; Ames, S.C.; Diehl, N.N.; Joseph, R.W.; Erik, P.; Castle, E.P.; David, D.; Thiel, D.D.; Broderick, G.A.; Parker, A.S. Evaluation of the association of prostate cancer-specific anxiety with sexual function, depression and cancer aggressiveness in men 1 year following surgical treatment for localized prostate cancer. Psycho-Oncology 2013, 22, 1328–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilt, T.J.; Jones, K.M.; Barry, M.J.; Andriole, G.L.; Culkin, D.; Wheeler, T.; Aronson, W.J.; Brawer, M.K. Follow-up of prostatectomy versus observation for early prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishna, S.; Fan, Y.; Jarosek, S.; Adejoro, O.; Chamie, K.; Konety, B. Racial disparities in active surveillance for prostate cancer. J. Urol. 2017, 197, 342–3493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odom, B.D.; Mir, M.C.; Hughes, S.; Senechal, C.; Santy, A.; Eyraud, R.; Stephenson, A.J.; Ylitalo, K.; Miocinovic, R. Active surveillance for low-risk prostate cancer in African American men: A multi-institutional experience. Urology 2014, 83, 364–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acar, C.; Schoffelmeer, C.; Tillier, C.; de Blok, W.; van Muilekom, E.; van der Poel, H.G. Quality of life in patients with low-risk prostate cancer. A comparative retrospective study: Brachytherapy versus robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy versus active surveillance. J. Endourol. 2014, 28, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, A.; Metcalfe, C.; Young, G.J.; Peters, T.J.; Blazeby, J.; Avery, K.N.; Dedman, D.; Down, L.; Mason, M.D.; Neal, D.E.; et al. Patient-reported outcomes in the ProtecT randomized trial of clinically localized prostate cancer treatments: Study design, and baseline urinary, bowel and sexual function and quality of life. BJU Int. 2016, 118, 869–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, J.L.; Hamdy, F.; Lane, M.; Mason, M.; Metcalfe, C.; Walsh, E.; Blazeby, J.M.; Peters, T.J.; Holding, P.; Bonnington, S.; et al. Patient-reported outcomes after monitoring, Surgery, or radiotherapy for prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1425–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasperzyk, J.; Shappley, W.; Kenfield, S.; Mucci1, L.A.; Kurth, T.; Ma, J.; Stampfer, M.J.; Sanda, M.G. Watchful waiting and quality of life among prostate cancer survivors in the physicians′ health study. J. Urol. 2011, 186, 1862–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietzak, E.J.; Van Arsdalen, K.; Patel, K.; Malkowicz, S.B.; Wein, A.J.; Guzzo, T.J. Impact of race on selecting appropriate patients for active surveillance with seemingly low-risk prostate cancer. Urology 2015, 85, 436–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastian, P.J.; Carter, H.B.; Bjartell, A.; Seitz, M.; Stanislaus, P.; Montorsi, F.; Stief, C.G.; Schröder, F. Insignificant prostate cancer and active surveillance: From definition to clinical implications. Eur. Urol. 2009, 55, 1321–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnet, K.L.; Parker, C.; Dearnaley, D.; Brewin, C.R.; Watson, M. Does active surveillance for men with localized prostate cancer carry psychological morbidity? Br. J. Urol. Int. 2007, 100, 540–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sægrov, S. Health, quality of life and cancer. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2005, 52, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpkin, A.J.; Tilling, K.; Martin, R.M.; Lane, J.A.; Hamdy, F.C.; Holmberg, L.; Neal, D.E.; Metcalfe, C.; Donovan, J.L. Systematic review and meta-analysis of factors determining change to radical treatment in active surveillance for localized prostate cancer. Eur. Urol. 2015, 67, 993–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiting, P.F.; Moore, T.H.M.; Jameson, C.M.; Davies, P.; Rowlands, M.; Burke, M.; Beynon, R.; Savovic, J.; Donovan, J.L. Symptomatic and quality-of-life outcomes after treatment for clinically localized prostate cancer: A systematic review. BJU Int. 2016, 118, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellardita, L.; Valdagni, R.; van den Bergh, R.; Randsdorp, H.; Repetto, C.; Venderbos, L.D.F.; Lane, J.A.; Korfage, I.J. How Does Active Surveillance for Prostate Cancer Affect Quality of Life? A Systematic Review. Eur. Urol. 2015, 67, 637–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittemore, R.; Knafl, K. The integrative review: Updated methodology. J. Adv. Nurs. 2005, 52, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punnen, S.; Cowan, J.; Dunn, L.B.; Carroll, P.R.; Cooperberg, M.R. A longitudinal study of anxiety, depression and distress as predictors of sexual and urinary quality of life in men with prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2015, 112, E67–E75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, S.; Leydon, G.; Eyles, C.; Moore, C.M.; Richardson, A.; Birch, B.; Prescott, P.; Powell, C.; Lewith, G. A quantitative analysis of the prevalence of clinical depression and anxiety in patients with prostate cancer undergoing active surveillance. Br. Med. J. Open 2015, 5, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Bergh, R.C.; Essink-Bot, M.L.; Roobol, M.J.; Wolters, T.; Schröder, F.H.; Bangma, C.H.; Steyerberg, E.W. Anxiety and distress during active surveillance for early prostate cancer. Cancer 2009, 115, 3868–3878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Bergh, R.C.; Essink-Bot, M.L.; Roobol, M.J.; Schröder, F.H.; Bangma, C.H.; Steyerberg, E.W. Do anxiety and distress increase during active surveillance for low risk prostate cancer? J. Urol. 2010, 183, 1786–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Bergh, R.C.; Korfage, I.J.; Roobol, M.J.; Bangma, C.H.; de Koning, H.J.; Steyerberg, E.W.; Essink-Bot, M.L. Sexual function with localized prostate cancer: Active surveillance vs radical therapy. Br. J. Urol. Int. 2012, 110, 1032–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Cerqueira, M.A.; Laranja, W.W.; Sanches, B.C.; Monti, C.R.; Reis, L.O. Burden of focal cryoablation versus brachytherapy versus active surveillance in the treatment of very low-risk prostate cancer: A preliminary head-to-head comprehensive assessment. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2015, 24, 929–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venderbos, L.D.; van den Bergh, R.C.; Roobol, M.J.; Schröder, F.H.; Essink-Bot, M.L.; Bangma, C.H.; Steyerberg, E.W.; Korfage, I.J. A longitudinal study on the impact of active surveillance for prostate cancer on anxiety and distress levels. Psycho-Oncology 2015, 24, 348–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruane-McAteer, E. An exploration of men′s experiences of undergoing active surveillance for favorable-risk prostate cancer: A mixed methods study protocol. BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punnen, S.; Cowan, J.; Carroll, P.R.; Cooperberg, M.R. Long term health related quality of life after primary treatment for localized prostate cancer: Results from the CaPSURE registry. The Journal of Urology. 2013, 189, e411–e412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ercole, C.; Krebs, T.; Prots, D.; Berglund, R.; Ciezki, J.; Campbell, S.; Fergany, A.; Gong, M.; Haber, G.P.; Jones, S.; et al. Patient-reported health related quality-of-life (hrqol) outcomes of patients on active surveillance: Results of a prospective, longitudinal, single-center study. J. Urol. 2014, 191, e665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, K.; Jeldres, C.; Johnston, R.; Cullen, J.; Odem-Davis, K.; Wolff, E.; Levie, K.; Hurwitz, L.; Porter, C. Health-related quality of life for men with low risk prostate cancer managed with active surveillance compared to a cancer-screening cohort without prostate cancer. J. Urol. 2014, 191, e147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, J.H.; Ollendorf, D.A.; Pearson, S.D.; Barry, M.J.; Kantoff, P.W.; Stewart, S.T.; Bhatnagar, V.; Sweeney, C.J.; Stahl, J.E.; McMahon, P.M. Active surveillance compared with initial treatment for men with low-risk prostate cancer: A decision analysis. JAMA 2010, 304, 2373–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, K.; Ahallal, Y.; Sjoberg, D.D.; Ghoneim, T.; Esteban, M.D.; Mulhall, J.; Vickers, A.; Eastham, J.; Scardino, P.T.; Touijer, K.A. Effect of repeated prostate biopsies on erectile function in men on active surveillance for prostate cancer. J. Urol. 2014, 191, 744–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegarty, J.M. Uncertainty and quality of life among men undergoing active surveillance for prostate cancer in the United States and Ireland. Am. J. Men′s Health 2008, 2, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazer, M.W. An internet intervention for management of uncertainty during active surveillance for prostate cancer. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2011, 38, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lokman, U.; Vasarainen, H.; Lahdensuo, K.; Erickson, A.M.; Taari, K.; Mirtti, T.K.; Rannikko, A. Prostate cancer active surveillance: Health-related quality of life in the Finnish arm of the prospective PRIAS-study. Three year update. Eur. Urol. Suppl. 2013, 12, e274–e275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasarainen, H.; Lokman, U.; Ruutu, M.; Taari, K.; Rannikko, A. Prostate cancer active surveillance and health-related quality of life: Results of the Finnish arm of the prospective trial. Br. J. Urol. Int. 2011, 109, 1614–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pham, K.N.; Wolff, E.M.; Banerji, J.S.; Wolff, E.M.; Levie, K.E.; Odem-Davis, K.; Banerji, J.S.; Rosner, I.L.; Brand, T.C.; L′Esperance, J.O.; et al. Prospective quality of life in men choosing active surveillance compared to those biopsied but not diagnosed with prostate Cancer. J. Urol. 2016, 196, 392–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerji, J.S.; Hurwitz, L.M.; Cullen, J.; Odem-Davis, K.; Wolff, E.M.; Levie, K.; Pham, K.N.; Porter, C.R. A prospective study of health-related quality of life outcomes for low-risk prostate cancer patients managed by active surveillance or radiation therapy. J. Urol. 2015, 193, e513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, J.; Litwin, M.S. Quality of life in men undergoing active surveillance for localized prostate cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. Monogr. 2012, 45, 242–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcox, C.B.; Gilbourd, D.; Louie-Johnsun, M. Anxiety and health-related quality of life (HRQL) in patients undergoing active surveillance of prostate cancer in an Australian centre. Br. J. Urol. Int. 2014, 113, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiler, D.; Randazzo, M.; Leupold, U.; Zeh, N.; Isbarn, H.; Chun, F.K.; Ahyai, S.A.; Baumgartner, M.; Huber, A.; Recker, F.; et al. Health outcomes research: Protocol-based active surveillance for low-risk prostate cancer: Anxiety levels in both men and their partners. Urology 2012, 80, 564–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazer, M.W.; Bailey, D.E.; Colberg, J.; Kelly, W.K.; Carroll, P. The needs for men undergoing active surveillance (AS) for prostate cancer: Results of a focus group study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2011, 20, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silberstein, J.L.; Feibus, A.H.; Maddox, M.M.; Abdel-Mageed, A.B.; Moparty, K.; Thomas, R.; Sartor, O. Active surveillance of prostate cancer in African American men. Urology 2014, 84, 1255–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson, P. Does active surveillance lead to anxiety and stress? Br. J. Nurs. 2014, 23, S4–S12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, J.; Burney, S.; Brooker, J.; Ricciardelli, L.A.; Fletcher, J.M.; Satasivam, P.; Frydenberg, M. Anxiety in the management of localized prostate cancer by active surveillance. Br. J. Urol. Int. 2014, 114, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvisi, M.F.; Bellardita, L.; Ricanti, T.; Villa, S.; Marenghi, C.; Bedini, N.; Villa, S.; Biasoni, D.; Nicolai, N.; Salvioni, R.; et al. Health related quality of life and coping in patients on active surveillance: Two-year follow-up. Eur. Urol. Suppl. 2013, 12, 159–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frydenberg, M.; Anderson, J.; Ricciardelli, L.; Burney, S.; Brooker, J.; Fletcher, J. Psychological stress associated with active surveillance for localized low risk prostate cancer. J. Urol. 2013, 189, e548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, G.; Clover, K.; Britton, B.; Mitchell, A.J.; White, M.; McLeod, N.; Denham, J.; Lambert, S.D. Wellbeing during active surveillance for localized prostate cancer: A systematic review of psychological morbidity and quality of life. Ann. Fam. Med. 2015, 5, 112–119. [Google Scholar]

- Barocas, D.A.; Alvarez, J.; Resnick, M.J.; Koyama, T.; Hoffman, K.E.; Tyson, M.D.; Conwill, R.; McCollum, D.; Cooperberg, M.R.; Goodman, M.; et al. Association between radiation therapy, surgery or observation for localized prostate cancer and patient-reported outcomes after 3 years. JAMA 2017, 317, 1126–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.C.; Basak, R.; Meyer, A.; Kuo, T.M.; Carpenter, W.R.; Agans, R.P.; Broughman, J.R.; Reeve, B.B.; Nielsen, M.E.; Usinger, D.S.; et al. Association between choice of radical prostatectomy, external beam radiotherapy, brachytherapy, or active surveillance and patient-reported quality of life among men with localized prostate cancer. JAMA 2017, 317, 1141–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Citation and Source/Country | Purpose and Setting | Design, Methods and Sample | Race/Ethnicity | Reported Instruments | Key Findings | Strengths and Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acar et al., (2014)/ Amsterdam, the Netherlands [29] | Purpose: To investigate QoL after different treatment modalities for low-risk PCa with questionnaires. Setting: Amsterdam, the Netherlands. | Design: Quantitative, non-RCT. Methods: Questionnaires mailed or emailed, follow up every 6 months, 2004–2011. Statistics: Descriptives, Kruskal–Willis, Mann-Whitnal Grelyss, Spearman Correlations, and non-parametric Wilcox signed rank test. Sample: 144 out of 2615 eligible, low-risk PCa patients. Response rate: Not listed. | Race/Ethnicity: Not indicated. | Reported Instruments: QoL-EORTC-QLQC30; PCa QoL-EORTC-QLQ-CPR25; Sexual function-IIEF-15; Incontinence and QoL-ICIQ-SF. | Key Findings: AS patients had stable scores for physical QoL during follow-up. AS patients had lowest decrease (30%), in SF during follow-up brachytherapy (59%) and RALP (71%). Brachytherapy and RALP patients had decreased scores on different measures particularly, EF and incontinence. | Strengths: This study compared multiple treatment options and compared baseline QoL to QoL post-treatment. Limitations: Non-randomized set up causes a treatment selection bias, 80% of patients were referred to the tertiary oncology center, small sample size, comorbidities may have affected treatment choice, no data on QoL effects of delayed local treatment in the AS group were collected. |

| Banerji et al., (2015)/ United States [59] | Purpose: A comparison of HRQoL between patients managed by active surveillance or radiation therapy. Setting: Center for Prostate Disease Research (CPDR) Multicenter National Database, United States. | Design: Quantitative, non-RCT. Statistics: Descriptives and GEE. Methodology: A prospective cohort of patients at the Center for Prostate Disease Research Multicenter National Data base. Sample: Selected 77 (19%) of AS and 57 (14%) treated with EBRT of 410 low-risk PCa patients. Response rate: Not listed. | Race/Ethnicity: Large portion of African Americans indicated, but specific numbers not indicated. | Reported Instruments: HRQoL was measured with the EPIC and the SF36. | Key Findings: Majority treated with AS 77 (19%). More AA′s chose RT. Both groups had similar HRQoL scores at baseline. AS patients did not have declines in bowel or general physical HRQoL unlike patients who received the RT. Significant results for worse BF among RT patients at 1 year of follow-up p < 0.05 and 2 years p < 0.05. Statistically significant results for declines in BF and UB for radiation patients at 2 and 3 years follow up, p < 0.05. Statistically significant declines in overall physical health at 2 years, p < 0.01. | Strengths: The study compared the concept of HRQoL in AS and RT. Focused on the physical aspects of HRQoL, as opposed to the psychological aspects. Highlight the benefits of selecting AS based on reported HRQoL. Limitations: A comparison of HRQoL based on demographic data, such as, race, age, and education who have provided additional factors regarding their experiences with AS. |

| Bergman and Litwin (2012)/ United States [60] | Purpose: To examine existing literature regarding HRQoL among men on AS, instruments that measure HRQoL, and studies that examined HRQoL for men on AS. Setting: N/A. | Design: Literature review. Methodology: Literature review, examination of existing studies. | Race/Ethnicity: Not indicated. | Reported Instruments: HRQoL was examined through, retrospective, national, and experimental studies conducted in the United States. | Key Findings: Physicians should advise men with prostate cancer of the impact of treatment on QoL. Sexual dysfunction and anxiety were present in men receiving AS. A 5-year follow-up indicated increased erectile dysfunction and urinary leakage among patients receiving AS compared to curative treatments. AS patients had less urinary obstruction. After 5 years, scores for BF, anxiety, depression, and general HRQoL were similar. | Strengths: This review of literature on HRQOL, encompasses, the concept of HRQOL, as well as, instruments utilized to examine HRQOL, and various studies which examined HRQOL. Limitations: The information would be easier to discern if it was presented in a table format. |

| Braun et al., (2014)/ New York, New York and Herne, Germany [53] | Purpose: To explore the hypothesis that serial biopsies can lead to reduced EF in men undergoing AS. Setting: New York, US and Herne, Germany. | Design: Quantitative, non-RCT. Methods: Questionnaires given to participants at scheduled clinic visits. Follow-up annually for 4 years. Statistics: Locally weighted scatterplot smoothing. Sample: 342 men on AS between 2000–2009. Response rate: Not listed. | Race/Ethnicity: indicated. | Reported Instruments: QoL and EF measured with the PHRQoL and 6 questions from the IIEF. | Key Findings: Small decrease in EF over a period in men undergoing AS. AS biopsies did not have a large impact on EF. | Strengths: Possible changes in EF were evaluated longitudinally. Limitations: Change in EF was not measured within days or weeks after biopsies, there was no control group to distinguish between the effects of aging alone versus those of aging and repeat biopsies. |

| de Cerqueira et al., (2015)/ Sao Paulo, Brazil [46] | Purpose: To identify the burden of three different protocol-based treatment options. Setting: Sao Paulo, Brazil. | Design: Quantitative, non-RCT. Methods: Questionnaires were given to participants and follow-up in 1 year. Statistics: Descriptives, Spearman correlations, and ANOVA. Sample: Invited 130, 100 excluded, final of 30 with very low risk PCa. Response rate: None listed. | Race/Ethnicity: Not indicated. | Reported Instruments: HRQoL measured by the SF-36, EF measured by 5 questions from the IIEF voiding functions measured by the IPSS, anxiety was measured by the BAI, hopelessness was measured by the BHS, depression was measured by the BDI. | Key Findings Patients who opted for AS reported higher levels of hopelessness and worse general health perceptions when compared to BT and FC. | Strengths: This study offered a comprehensive assessment of low-toxicity prostate cancer therapies and used many different standardized instruments. Limitations: Very small sample size and age difference is a possible confounder. |

| Donovan et al., (2016)/ United Kingdom [31] | Purpose: To investigate the effects of active monitoring, RP, and radical radiotherapy with hormones on patient-reported outcomes in the Prostate Testing for Cancer and Treatment (ProtecT) trial. Setting: United Kingdom. | Design: Quantitative, randomized. Methods: Questionnaires given to participants. Follow-up at 6 and 12 months over 6 years. Statistics: Descriptives, logistic models, two-level linear models. Sample: 2896 identified with PCa in 1999–2009, 1643 were randomized. Response rate: 85%. | Race/Ethnicity: Not indicated. | Reported Instruments: UF was measured by the ICIQ; SF and BF was measured by the EPIC, general health was measured by the SF-12, anxiety and depression were measured by the HADS, cancer-related QoL was measured by the EORTC QLQ-C30. | Key Findings: AS had little effect on urinary continence; EF decreased from year to year; BF and BB remained the same. | Strengths: Long-term study with a large sample size. Limitations: The forms of treatment for prostate cancer were not consistent in the study and men switched treatments. Lack of diversity. |

| Ercole et al., (2014)/ Cleveland, Ohio [50] | Purpose: Analyze voiding, BF, SF, urinary incontinence, and physical/emotional functioning among patients managed by AS, RP, and BT. Setting: Cleveland, Ohio. | Design: Quantitative, non-RCT. Methods: Instrument was given to patients. Follow-up at 6 months and 12 months over 2 years between 2007 and 2013. Sample: 590 patients with PCa. Response rate: None listed. | Race/Ethnicity: Not indicated. | Reported Instruments: The domains were measured by Qual Life Res 2000. | Key Findings: All of the domains regarding QoL for patients on AS were stable over 1-2 years for UF and BF. AS was significantly better than BT. SF and incontinence for AS was significantly better than RP. | Strengths: Use of instrument for self-reported functional outcomes and time was treated as categorical instead of continuous to reflect possible non-linear time trend. Limitations: Possible selection bias, making results less generalizable. |

| Hayes et al., (2010)/ United States [52] | Purpose: Examine QoL risks and benefits among patients receiving AS and other initial therapies as a treatment for PCa. | Design: Quantitative, non-RCT Methodology: Simulation decision model analysis utilizing BT, intensity-modulated radiation therapy, RP or AS. Statistics: Descriptives, State transition model, 1-way multiway sensitivity analyses with a 1-time input. Sample. 500 samples consisting of 100,000 individual trials, however a definite sample size was not specified. Hypothetical groups of men aged 65 years and older diagnosed with localized low risk PCa. Response rate: Not listed. | Race/Ethnicity: Not indicated. | Reported Instruments: A model was utilized based on previous sources from the literature which included the components of annual probabilities, base case estimates, and a range used in sensitivity analysis. | Key Findings: Men over 65 which received AS were expected to live an additional 6 months of quality of life age expectancy. Despite high risk for death from PCa, the men on AS still maintained the highest quality adjusted life-years. | Strengths: An examination of QoL based on adjusted life-years. The study is a first to use decision analysis and a model which used previous literature to determine probabilities and utilities, which was innovative. Limitations: The participants were hypothetical and there was only one age for the men, 65 years. The model only included what was reflected in the literature. There was not a clear sample size provided for the hypothetical patients. Results indicated there were. |

| Hegarty et al., (2008)/ United States and Ireland [54] | Purpose: The purpose is to explore uncertainty and QoL among men 65 and over undergoing AS as a treatment for prostate cancer in America and Ireland. | Design: Quantitative, non-RCT. Questionnaires mailed, no follow-up. Statistics: Descriptives, Cronbach alpha score. Sample: 92 questionnaires mailed to patients in Ireland, 58 returned, only 2 agreed to participate. In America, 27 agreed to participate for a total of 29. | Race/Ethnicity: Not indicated. | Reported Instruments: Uncertainty measured by the MUIS-C, QoL was measured using the Quality of Life Index, the Cancer Version for QoL, the UCLA-PCI for measuring six domains (urinary function, urinary bother, bowel function, bowel bother, sexual function, and sexual bother) related to QoL among PCa survivors. | Key Findings: Uncertainty was higher for men in America undergoing AS. The HRQOL scores were similar among patients in Ireland and America. The men in Ireland had lower mean and social functioning compared to men in America. Men in Ireland also reported more energy and improved general health. The men in Ireland also indicated they had more issues with UF and less concern with sexual issues. | Strengths: There was a comparison of AS treatment for PCa among men in Ireland and America. Limitations: A small sample size and it was a convenience sample. Lack of racial diversity among the samples. |

| Jeldres et al., (2015)/ United States [6] | Purpose: To assess the impact of PCa management strategy on disease-specific and general HRQoL outcomes over time. Setting: Sites included Madigan Army Medical Center (Tacoma, Wash), Naval Medical Center (San Diego, Calif), Virginia Mason (Seattle, Wash), and Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (Bethesda, Md). | Design: Quantitative, non-RCT Methods: Questionnaires were administered to participants. Annual follow-up for 3 years. Statistics: Descriptives, Welch tests, chi-square, Cochran–Armitage, GEE. Clinically meaningful was established as a 0.5 difference in the standard deviations among the baseline scores in each cohort. Sample: 745 eligible 305 participated which were enrolled in the Center for Prostate Disease Research (CPDR) Multicenter National Database. | Race/Ethnicity: White: 224 African American: 58 Hispanic: 9 Asian: 12 Unknown: 2. | Reported Instruments: Function and bother for urinary, sexual, bowel, and hormone domains were evaluated by the EPIC and mental components were measured by the SF-36. | Key Findings: In the AS cohort, there were no statistically significant or clinically meaningful declines in QoL. The RP cohort experienced clinically meaningful and statistically significant declines in SF, sexual bother, and UF scores that persisted for 3 years. | Strengths: This study is one of the first to report on longitudinal HRQoL in a carefully defined, prospective cohort of patients who underwent AS; the multidisciplinary approach increased study strength; racial diversity; use of qualified HRQoL metrics. Limitations: Participants were self-selected and not randomized into treatment groups, so it is possible that the patients who chose AS were less anxious than those who chose treatment, small AS sample, generalizability of our findings may also be limited given our strict eligibility criteria and unique cohort features (example: most of the subjects were military health care beneficiaries). |

| Kasperzyk et al., (2011)/ Boston, Massachusetts [32] | Purpose: To examine patient reported outcomes among patients with PCa treated with watchful waiting in a nationwide cohort. Setting: Multiregional, American, community-based setting. | Design: Quantitative, non-RCT Methods: Questionnaires administered to patients. Only largest follow-up reported, which was at 7.6 years. Statistics: Descriptives, Cox proportional, Hazards regression, logistic regression, t-tests, chi-square, Fisher exact tests, Wilcox rank-sum tests, D′Amico criteria. Sample: Invited 3313 invited, 1366 participated at baseline, 1230 final sample. Patients from the Physicians′ Health Study. | Race/Ethnicity: White: 95.6% Black: 0.9% Asian: 1.4% Other: 2.1% | Reported Instruments: QOL questions included items from the UCLA-PCI and the EPIC. | Key Findings: When watchful waiting and AS was compared to immediate treatment, patients who underwent watchful waiting had lower urinary incontinence and impotence but more common obstructive urinary symptoms. | Strengths: Chi-square test, Wald test, and logistic regression used. Limitations: Baseline information not available, recall bias, could not differentiate between AS and watchful waiting, could not examine lethal PCa as an endpoint. |

| Kazer et al., (2011)/ United States [55] | Purpose: Examine the impact of the intervention, Alive and Well on decreasing uncertainty, improving self-management, self-efficacy and QoL in men undergoing AS for prostate cancer. Setting: Two urological practices at academic institutions in the Northeastern, United States. | Design: Quantitative, non-RCT, single-subject design. Questionnaires were completed online, and participants were informed to visit the Alive and Well website as an intervention Follow-up at weeks 5 and 10. Statistics: Pearson correlations. Sample: Started with 20 participants and final was 9. Response rate: Attrition rate listed as 33%. | Race/Ethnicity: White: 9. | Reported Instruments: Self efficacy scale adapted developed by Lorig et al. (1996), Uncertainty measured by the MUIS-C, QoL was measured with the UCLA-PCI. | Key Findings: There were improvements in 8 of the 12 subscales for QoL at T2 when compared to baseline. QoL scores went back to baseline at T3. | Strengths: The novelty of a solely online design. A study which is focused on identifying factors which impact participants QoL while undergoing AS. Limitations: Attrition rate of 33% yielded a small sample. The use of solely online instruments among an older population may have caused attrition. |

| Kazer et al., (2011)/ United States [63] | Purpose: Conduct focus groups to explore the psychosocial and educational needs of men undergoing AS for prostate cancer. Setting: United States. | Design: Qualitative Methodology: Structured interview questions were provided to the focus groups, which lasted approximately one hour. A male researcher conducted the interviews, which were audio recorded. Sample: 7 participants participated in two focus groups. | Race/Ethnicity: White: 7. | Reported Instruments: A set of focus group questions was developed for the participants. | Key Findings: The following themes were identified from the study: sources of information, disease monitoring/vigilance, myths/misinformation/frequently asked questions, and Health promotion and taking charge. Participants turned to the internet to obtain information, the men made life style changes after the diagnosis of prostate cancer. | Strengths: Qualitative study to explore the impact of AS on HRQOL. Two researchers examined the data. A male researcher provided the questions to the participants. Limitations: There was a lack of racial/ethnic diversity among the participants. |

| Lane et al., (2016)/ Nine cities in the United Kingdom [30] | Purpose: To examine the patient reported outcomes of men diagnosed with and receiving treatment for localized PCa. | Design: Quantitative, randomization Methods: Paper questionnaires were distributed to patients at clinics during their initial prostate specific antigen screening and biopsy. Some participants were randomized to complete the questionnaires by mail at 6 months and yearly for 10 years. Sample: 2417 identified, but 1438 completed the questionnaires and received the biopsies. Response rates: Not listed. | Race/Ethnicity: 99% White. | Reported Instruments: QoL measured by the EQ-5D-3L, Urinary and sexual functions except for hormonal domains measured by the EPIC, incontinence measured by the ICIQ-UI, l Continence measured by the ICSmaleSF, anxiety and depression measured by the HADS, the SF-12 was used to measure general mental and physical health. | Key Findings: AS was second to RT as the most common form of treatment. The lowest scores for issues with SF and problems was among the AS group. Participants receiving AS had higher anxiety and depression, health utility, mental, and physical health scores. There was no difference among the groups for significant problems with erectile dysfunction. | Strengths: Large multi-site study that utilized randomization for completing questionnaires. High completion rate of the questionnaires. Limitations: Some participants only completed the baseline questionnaires which could not be compared to subsequent follow up results from other participants. The baseline questionnaire was completed at the initial biopsy, which may have been a stressful time for participants. Results cannot be generalized to non-white individuals. |

| Lokman et al., (2013)/ Helsinki, Finland [56] | Purpose: To investigate the effect of AS protocol on HRQoL, erectile function and UF in low-risk PCa patients. Setting: Helsinki University Central Hospital. | Design: Quantitative, non-randomized. Methods: Questionnaires were given to patients annually for 3 years. Statistics: Descriptives, paired t-tests. Sample: 224 patients enrolled in the Finnish arm of the Prostate Cancer Research. International: AS (PRIAS) study. Response rate: Not listed. | Race/Ethnicity: Not indicated. | Reported Instruments: General health measured by the RAND 36, EF measured by the IIEF-5 and PCa symptoms measured by the IPSS. | Key Findings: Using a generic QoL questionnaire (RAND 36), no deterioration of QoL was apparent after 3 years of follow up in a prospective AS cohort. No detrimental effect on EF. | Strengths: Prospective design and use of standardized questionnaires, long term follow up and baseline scores were obtained. Limitations: Lack of randomization when selecting patient population. |

| Parker et al., (2016)/ Houston, Texas [16] | Purpose: To evaluate prospectively the associations between illness uncertainty, anxiety, fear of progression and general and disease-specific QoL in men with favorable-risk PCa undergoing AS. Setting: Houston, Texas. QoL outcomes for men who discontinued AS. | Design: Quantitative, non-RCT. Methods: Participants completed questionnaires at the time of enrollment and every 6 months for up to 30 months. Statistics: Descriptives, mixed models, and compound symmetry covariance structure. Sample: 180 men during 2006–2012 with favorable low-risk PCa. Response rate: Not listed. | Race/Ethnicity: White: 86% Black: 6.7% Hispanic: 6.1% Asian: 1.1%. | Questionnaires assessed illness uncertainty, anxiety, prostate-specific QoL using the EPIC, SF-12, MUIS, and the STAI. | Key findings: QoL was stable after a 2.5-year follow-up, which indicated a decrease in SF scores. An increased PSA score was associated with a decreased urinary and bowel score. As illness uncertainty increased, urinary, bowel, sexual, hormonal, and satisfaction scores decreased. An increase in anxiety predicted lower urinary, bowel, sexual, hormonal, and satisfaction scores. | Strengths: This study is one of the largest prospective studies to examine QoL, the influence of psychosocial factors on QoL, and fear of disease progression for men who are on AS. This study controlled for demographic and cancer-related variables. Limitations: The cohort at this specialized cancer center may be different from other cohorts; AS criteria was different from other trials; the sample was 86% white, so it may be difficult to generalize the results to other races and ethnicities; this study did not assess psychosocial and QoL outcomes for men who discontinued AS. |

| Pham et al., (2014)/ Seattle, Washington [51] | Purpose: To specifically assess the HRQoL impact of AS compared to a control group of men who had undergone negative PNB. Setting: Multidisciplinary clinic. | Design: Quantitative, non-RCT, prospective cohort study. Follow-up annually for 2 years. Methods: Questionnaires were given to patients at baseline and PNB. Statistics: Descriptives and univariate predictor analysis. Sample: 326 (223 PNB patients and 103 AS patients from the Center for Prostate Disease Research (CPDR) multi-center national database during 2007–2012. Response rate: Not listed. | Race/Ethnicity: White: 326 Non-caucasian:133. | Reported Instruments: The SF-36 measured physical and mental health and the EPIC measured sexual, urinary, and bowel function and bother. | Key Findings: AS had statistically significant declines in SF at 1 and 2 years and UF at 2 years when compared to PNB negative patients. Importantly, there were no HRQoL differences in BF, physical health or mental health between the 2 groups. | Strengths: Use of a control group. Limitations: Relatively small sample size. |

| Pham et al., (2016)/ [58] | Purpose: Evaluate HRQoL outcomes in men on AS compared to men followed negative PNB, non-cancer. Setting: Various institutions. | Design: Quantitative, randomization, prospective study. Methods: Questionnaires administered annually for 3 years at clinic visits for PNB. were given to patients. Statistics: Welch′s t-test, chi-square, GEE, Fisher′s exact test, Cochran-Armitage trend tests. Sample: 1204 eligible, 787 had PCa and 411 had low-risk PCa and 89 on AS. Response rates: Non- cancer (61%) and AS (67%). | Race/Ethnicity: White: 343 African American: 79 Hispanic: 19 Asian: 47 Other: 14 Unknown: 7. | Reported Instruments: HRQoL was assessed using the SF-36 and EPIC questionnaires. | Key Findings: AS patients reported higher scores at baseline and 1 year for UF and UB, BB, hormonal bother, physical component summary, role-physical, bodily pain and social functioning subscales. Projected trends over time indicated decreased UF, BF and bodily pain among the men receiving AS. | Strengths: Use of randomization. This study is the first to compare prospective, longitudinal HRQoL in patients who underwent AS to that of subjects with a negative PNB. Limitations: Absence of baseline data. |

| Punnen et al., (2013)/ San Francisco, California [49] | Purpose: To assess long-term QoL in men with PCa using a longitudinal, nationwide, PCa registry. Setting: Nationwide, United States. | Design: Quantitative, non-RCT. Methods: Questionnaires administered to patients yearly for follow-up over 10 years. Statistics: Descriptives and repeated measures mixed model regression analysis. Sample: Cohort consisted of 3777 in which 2018 (60%) underwent RP, 686 (20%) underwent BT, 392 (12%) underwent external beam RT, 197 (6%) underwent primary androgen deprivation therapy and 84 (2%) underwent AS or watchful waiting from the Cancer of the Prostate Strategic Urologic Research Endeavor (CaPSURE) database. Response rate: Not listed. | Race/Ethnicity: Not indicated. | Reported Instruments: QoL was assessed using the UCLA-PCI and the SF-36. | Key Findings: Most had initial declines in HRQoL in the first 2 years after treatment. Almost no change in years 3 through 10. | Strengths: Longitudinal study from a nationwide PCa database. Limitations: Lack of randomization. |

| Punnen et al., (2013)/ San Francisco, California [41] | Purpose: To assess the presence of depression, anxiety, and distress among patients who received AS and RP and the impact on urinary and sexual QoL at baseline and follow-up. Setting: University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Dept. of Urology. | Design: Quantitative, non-RCT. Methods: Questionnaires from the institutional Urologic Oncology Database. Follow-up at 1 and 3 years from baseline. Sample: 864 invited, 679 participated AS (122) or RP (557). Response rate: 77% baseline reported. | Race/Ethnicity: White: 622 Asian/Pacific Islander: 31 African American: 9 Latino: 8 Mixed: 4 Other: 4 Native American: 1. | Reported Instruments: Depressive symptoms were assessed using the PHQ-9, anxiety symptoms were measured using the GAD-7, distress was ascertained using the DT, erectile dysfunction measured by the SHIM, UB, sexual bother assessed by the EPIC-26, urinary issues assed by the IPSS. | Key Findings: Similar rates of depression, anxiety and distress among patients receiving AS or RP over time. Higher levels of depression or anxiety were associated with worse SF and bother, while elevated levels of distress were associated with UF on follow-up. | Strengths: Use of several measures for psychological and physiological distress. Limitations: Did not assess for past medical history of depression or anxiety, men might be less likely to endorse mental health symptoms on an online survey; potential bias. |

| Seiler et al., (2012)/ Switzerland [62] | Purpose: To determine the level of anxiety and HRQoL among men receiving AS and their partners. Setting: Switzerland. | Design: Quantitative retrospective design. Methods: Men were recruited from the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer to complete the questionnaires. Follow up at 17, 32, 59, and 136 months, data collected between February and August 2010. Statistics: Wilcox test, ANOVA, binary logistic regression Sample: 283 invited. There were a total of 133 (n = 266) couples in the study. Response rate: 46.9%. | Race/Ethnicity: Not indicated. | Reported Instruments: Anxiety and depression measured with the HADS and the MAX-PC, aspects of QoL measured with the EORTC QLQ-30. | Key Findings: Low anxiety and distress levels were reported by patients and their partners. The distress level for patients and their partners did not reach a clinically relevant level. The partners had higher HRQoL scores for the domains of pain, global health status, physical and emotional functioning, fatigue, dyspnea, insomnia, and constipation. There was an association among elevated anxiety levels in the partners and the length of time on AS, lower general health status of the partners, and decreased emotional functioning. | Strengths: The study examined QoL among patients on AS for PCa as well as their partners. Comparisons were made to examine level of anxiety among the men and their partners. Limitations: The study was from a single-center in a small country. There was no control group and some of the data were based on recall, which may decrease the accuracy of the information. |

| Silberstein et al., (2014)/ New Orleans, Louisiana [64] | Purpose: A review of the literature on AS among AA men due to AA remaining at greater risk of disease progression. Setting: New Orleans, Louisiana. | Design: A review of the literature. Methods: Conducted utilizing the electronic databases Medline (PubMed). The inclusion dates were articles published through March 2014. The articles were categorized into the following groups retrospective studies, prospective observational studies, and prospective randomized trials. Sample: A specific number of articles was not indicated in the review of literature. | Race/Ethnicity: Retrospective studies-African American: 256 out of 1801, Prospective observational- African American: 125, Prospective randomized trials-American: 30% White 70%. | Reported Instruments: There were no instruments due to the study being a review of literature. | Key Findings: The majority of studies were small without any reported power, from a single institution and the retrospective studies had cohorts which lacked consistent findings regarding the safety of AS for AA men. The pathological features for AA men with low risk prostate cancer tended to be worse than those for White men. There may be a need for better imaging among AA men due to the location and size of the tumor. AA men on AS may have increased progression of prostate cancer or choose to forego AS a treatment. AS can still be a viable option of treatment for this high-risk population. | Strengths: The article is a review of literature which dates back to the oldest electronic source through 2014. Limitations: A limitation is that only one electronic database was utilized in the study. The inclusion of additional databases could have produced an abundance of articles for the manuscripts. The review did not focus on the type of instruments in the studies. |

| Simpson (2014)/ Canterbury, England [65] | Purpose: (1) A rapid literature search regarding the psychological impact of AS for treatment of patients with PCa. (2) Examining who assumes responsibility for the patient follow up on AS. Setting: Canterbury, England. | Design: A review of the literature utilizing, CINAHL plus with full text online, MEDLINE, text books, and journal articles. The article focused on the concepts of prostate cancer staging and grading, AS guidelines for practice, and psychological impact. Sample: A specific sample size was not indicated. | Race/Ethnicity: Not indicated. | Reported instruments: The SF36, Health Status Survey, measures HRQoL, the perceived stress scale, the Sexual Function Score and Prostate Cancer Index. The Memorial Anxiety Scale for Prostate Cancer (MAX-PC), IIEF-5 and the IPSS assessed stress and functional issues. | Key Findings: QoL determined from PCa treatments. Patients should only engage in AS if they are psychologically prepared to accept the monitoring of their PCa. Close monitoring of patients on AS for PCa is needed to further assess their psychological well-being. Trained nurse clinical specialist in the area of communications can be utilized to follow up with the psychological assessments of patients receiving AS. Education is a key component for patients receiving AS for PCa. | Strengths: The literature review appeared to be exhaustive in its use of electronic databases and the author′s own personal resources. Limitations: There was a lack of notation regarding the process for identifying, including, and excluding sources in the literature review. |

| Vasarainen et al., (2011)/ Helsinki, Finland [57] | Purpose: To analyze longitudinal changes in general, mental and physical QoL and urinary and erectile function in patients with low-risk PCa on AS. Setting: Finland. | Design: Quantitative, non-RCT. Methods: Questionnaires completed at the start of AS and at the first biopsy. Follow-up at 1 year. Statistics: A paired t -test, Correlation analysis, Pearson chi-square. Sample: 124 eligible and final sample of 80 from the Finnish arm of the Prostate Cancer Research. International: Active Surveillance (PRIAS) study. Response rate: 85% baseline questionnaires and 94% completed baseline and follow-up. | Race/Ethnicity: Not indicated. | Reported Instruments: General HRQL was assessed with the RAND 36-Item Health Survey (RAND-36), EF assessed with the IIEF-5, and urinary symptoms with the IPSS. | Key Findings: The low-risk PCa patients who received AS did not experience negative impacts on their QoL. UF and EF did not produce statistically significant changes. At one-year follow-up there were no differences in the QoL factors of mental and physical changes. Among the 8 QoL dimensions, only physical role improved and was statistically significant. Patients receiving AS experienced significantly better general mental and physical HRQL than the Finnish male population. | Strengths: Prospective design and various questionnaires. Limitations: Lack of randomization. |

| van den Bergh et al., (2012)/ The Netherlands [45] | Purpose: To compare SF of men with localized PCa on AS with similar patients who received radical therapy. Setting: Erasmus University Medical Centre and of participating local hospitals. | Design: Quantitative, no-RCT. Methods: Questionnaires were administered at the time of diagnosis or at the time of their treatment. Follow was done at 6 and 18 months for the AS group, 12 months for the RP and RT group. Statistics: Multivariable analysis, independent sample t-tests, and linear regression analysis. Sample: A total of 266 (AS = 129; RP = 67; RT = 70) patients with localized PCa. Response rate: Only listed for AS patients, 129 completed baseline questionnaires and 60% completed at follow-up. | Race/Ethnicity: Not indicated. | Reported Instruments: Questionnaires contained 10 items on SF, the mental and physical component summary from the SF-12, depression was assessed with the CES-D and general anxiety was measured with the STAI-6. | Key Findings: Fewer men undergoing AS were less sexually active due to EF when compared with patients who received combined treatment. more men from the active Sexual activity was increased among the men AS group along with decreased issues with EF. | Strengths: Use of Comparison of treatment groups for PCa. Limitations: Not randomized, no baseline measurement of SF. |

| Wilcox et al., (2014)/ Gosford, Australia [61] | Purpose: To assess anxiety QoL and understanding of AS in a cohort of patients enrolled in AS for PCa. Setting: Gosford Hospital and Gosford Private Hospital. | Design: Quantitative, non-RCT. Methods: Patients were mailed questionnaires to complete and return. No follow-up. Sample: 61 were invited to participate and 47 responded. Response rate: 77%. | Race/Ethnicity: Not indicated. | Reported Instruments: SF was assessed using the IIEF-5, voiding using the IPSS and the MAX-PC measured of PCa specific anxiety. | Key Findings: There were low levels of anxiety among the patients on AS and there was no difference in their QoL. Patients on AS did not experience difficulties with UF or EF while on AS. | Strengths: This study represents one of the first Australian investigations on HRQL and anxiety in men on AS of prostate cancer. Limitations: Small sample size. |

| Citation and Source/Country | Purpose and Setting | Design, Methods and Sample | Race/Ethnicity | Reported Instruments | Key Findings | Strengths and Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alvisi et al., (2013)/ Milan, Italy [67] | Purpose: To investigate the changes in HRQoL and adjustment to the first 2 years on AS. Setting: PRIAS database. | Design: Quantitative, non-RCT. Methods: Questionnaires completed at enrollment, 10 after diagnostic biopsy, 12 months after re-biopsy and 24 months. Statistics: Repeated measure analyses of variance were performed to test changes over time and Bonferroni correction. Sample: 208 patients. Response rate: At 10 months 156 completed questionnaires, 12 months had 109 completed questionnaires, and at 24 months 62 completed questionnaires. | Race/Ethnicity: Not indicated. | Reported Instruments: HRQoL domains were measured by the FACT-P; strategies of coping with cancer were measured by the Mini-MAC. | Key Findings: Patients on AS reported high levels of physical and psychological wellbeing throughout the first two years. QoL was not impaired by the idea of living with an untreated cancer. | Strengths: Long term study. Limitations: Patients selected may have already had low anxiety. |

| Anderson et al., (2014)/ Victoria, Australia [66] | Purpose: Describe a range of anxieties among men on AS for PCa and determine which of these anxieties predicted HRQOL. Setting: Cabrini Health in Victoria, Australia. | Design: Quantitative, non-RCT. Methods: Questionnaire were mailed to eligible patients. No follow-up. Statistics: Descriptives, Pearson′s correlations, and hierarchical regression. Sample: 260 men on AS were invited. 86 returned the questionnaires. Response rate: 33% | Race/Ethnicity: Not indicated. | Reported instruments: Psychological measures including the HADS, STAI, MAX-PC and the FACT-P anxiety; fear of reoccurrence; sociodemographic information. | Key findings: Men in the study had normal levels of general anxiety and illness-specific anxiety and high PCa related HRQoL. Age, trait anxiety and fear of recurrence were significant predictors of PCa related HRQoL. | Strengths: Multiple psychological measures were included to represent a wide range of anxieties. Limitations: results should be considered in the context of sample characteristics, the study had a correlational design (which cannot establish cause-effect relationship), use of only one facility. |

| Bellardita et al., (2012)/ Milan, Italy [39] | Purpose: Presentation of preliminary results for the observation of HRQoL, adjustment to disease and mental health of some patients from the PRIAS: AS study. Setting: Milan, Italy. | Design: Quantitative, non-RCT. Methods: The PRIAS database used several studies, the current study did not include follow-up information. Statistics: Descriptives. Sample: 70 participants between September 2007 and 2009 from the PRIAS cohort. | Race/Ethnicity: Not indicated. | Reported instruments: HRQoL was measured using the FACT-P, the Mini-MAC, assessed how patients cope with cancer; the SCL-90 report assessed patient′s mental health status. | Key Findings: Very high scores for HRQoL and no issues with adjusting to cancer. AS seemed to preserve QoL without adding any mental health issues. | Strengths: Use of longitudinal database comprised of data from 100 medical centers in 17 countries. Limitations: Possible selection bias. |

| Burnet et al., (2007)/ London, UK [35] | Purpose: To investigate anxiety and depression in patients with localized PCa managed by AS and those that selected immediate treatment. Setting: London, UK. | Design: Quantitative, non-RCT, cross-sectional. Methods: Participants received questionnaires in outpatient clinics. No follow-up. Statistics: Descriptives, One- way ANOVA, Least significant difference, chi square, and Bi-serial correlations. Sample: 764 patients were identified, 493 had early stage PCa, 353 completed the HADS, 24 excluded based on responses, final count of 329. Response rate: 72 % completed the HADS out of the 353. | Race/Ethnicity: White: 307 Other: 22. | Reported instruments: Anxiety and depression assessed by the HADS. | Key Findings: AS, compared to immediate treatment, did not cause an increase in anxiety or depression. | Strengths: Comparison of AS and immediate treatment for psychological distress. Limitations: Lack of randomization and use of only one measure for anxiety and depression. |

| Carter et al., (2015)/ Australia [69] | Purpose: (1) Examine the impact of AS on the patient′s psychological well-being and QoL. (2) Comparison of AS with active treatments for impact on psychological health. Setting: Australia. | Design: Systematic review. Methodology: the PRISMA guidelines were utilized to conduct the review. The following data bases were searched: Medline, PsycINFO, EMBASE, CINHAL, Web of Science, Cochrane Library and Scopus. Inclusion criteria were articles published January 2000–2014. | Race/Ethnicity: Not indicated. | Reported Instruments: The following measures were reported in the systematic review: HADS (8–10 borderline and >10 clinical), MAX-PC (P27), EORTC QLQ-C30, STAI-6 (>44), CES-D (P16), DCS (>37.5), STAI E, SF-36, UCLA-PCI, QLI- MUIS, SCL-90, FACT-P, and Mini-MAC. | Key Findings: There were 34 articles that met the inclusion criteria, 24 observational, 8 RCTs, and 2 interventional studies. No adverse impact from AS on psychological well-being. and no differences in psychological wellbeing compared to active treatments. | Strengths: Rigor of using a systematic review and the PRISMA guidelines. Limitations: Only Western countries and English language were included in the study. No consideration for men who started on AS and later chose an active treatment. Longitudinal studies did not have final results. |

| Frydenberg et al., (2013)/ Melbourne, Australia [68] | Purpose: To describe the anxieties among men on AS, and which anxieties predicted HRQoL. Setting: Melbourne, Australia. | Design: Quantitative, non-RCT. Methods: Questionnaires distributed to patients at a urologist′s office. No follow-up. Statistics: Descriptives. Sample: 265 men from a urologist′s AS database identified. 104 participated in the study. Response rate: Not indicated. | Race/Ethnicity: Not indicated. | Reported Instruments: Anxiety and depression were measured by the HADS, PCa specific anxiety was measured by the MAX-PC, state trait anxiety was STAT, illness perception measured by the IPQ-R and functional assessment of PCa measured by the FACT-P. | Key Findings: Low levels of anxiety and high HRQOL among AS patients. Patients receiving AS had a fear of recurrence. | Strengths: Use of multiple questionnaires for anxiety and psychological distress. Limitations: All patients from a single practice instead of multiple sites. |

| Ruane-McAteer et al., (2016)/ Northern Ireland [48] | Purpose: (1) Examine anxiety in non-cancer men, men who received AS for PCa, and men who received active treatment for PCa. (2) Explore patient′s experience of being treated with AS for PCa. Setting: Northern Ireland. | Design: Mixed-methods, Phase 1 quantitative-questionnaires distributed at the Northern Ireland Cancer Centre (NICC) and Belfast City Hospital and follow-up questionnaires every 3 months for 12 months among all groups. Phase 2 qualitative semi structured interviews. Statistics: Descriptives, hierarchical linear modeling, univariate analysis (t-test) Sample: 180 each group consisted of 90 men. Response rate: Not listed. | Race/Ethnicity: Not indicated. | Reported Instruments: Demographic data measured by EPQ, depression and anxiety measured with the CES-D, STAI-6, and the MAX-PC, uncertainty measured by the MUIS-C, DCS, DRS, and PCa specific functions were measured by the EPIC. | Key Findings: The study has yet to be implemented and is only a description of what is to occur. | Strengths: The study is novel in that is the first to incorporate baseline data prior to treatments being decided, incorporation of a control group which includes men without cancer in a mixed methods study. Limitations: There are yet to be limitations determined as the study has yet to be implemented. |

| van den Bergh et al., (2009)/ Rotterdam, the Netherlands and Amsterdam, the Netherlands [43] | Purpose: To examine the levels of decisional conflict, depression, and generic PCa specific anxiety for selecting for AS. Setting: Rotterdam, the Netherlands and Amsterdam, the Netherlands. | Design: Quantitative. Methods: Quantitative, non-RCT. Questionnaires were mailed to the subjects′ home address between May 2007 and May 2008. Statistics: Descriptives, Univariate linear regression analyses, Multivariate linear regression analyses. Sample: 150 eligible, 129 questionnaires returned. Response rate: 86%. | Race/Ethnicity: Not indicated. | Reported Instruments: Depression was assessed with the CES-D. Anxiety was assessed with the abridged STAI-6. PCa-specific anxiety was assessed MAX-PC. General health was assessed using the SF-12. | Key Findings: More than 3/4 of the participants had better scores for the reference values for clinically significant uncertainty based on their treatment decision, depression, generic anxiety, and PCa-specific anxiety. The majority of men had better distress and anxiety scores compared to reference values and other treatments for PCa. | Strengths: High response rate and the use of various questionnaires to assess psychological and mental health issues. Limitations: Patients may have already had low anxiety and distress due to already being on AS. No control group for comparison. |

| van den Berg et al., (2010)/ The Netherlands [44] | Purpose: To assess anxiety and depression among men receiving AS and their reasons for discontinuation. Setting: Erasmus University Medical Centre. | Design: Quantitative, non-RCT. Methods: Questionnaires were mailed to patients from the PRIAS study with a PCa diagnosis of less than 6 months. Follow-up 9 months after diagnosis. Statistics: Descriptives, multivariate linear regression analysis, paired samples t-tests Sample: 150 men at baseline and final of 129. Response rate: 86% for 129 out of 150 and 90% for 108 out of 120. | Race/Ethnicity: Not indicated. | Reported Instruments: Decisional conflict were assessed with the DCS depression was assessed with the CESDS, generic anxiety with the STAI, PCa specific anxiety with the MAX-PC. | Key Findings: Anxiety and distress appeared to be low during the first 9 months of AS. A total of 9 men discontinued AS. | Strengths: High response rate and use of multiple instruments to assess anxiety and depression. Limitations: Patients may have already had decreased rates of anxiety and depression due to already being on AS. |

| Venderbos et al., (2015)/ Rotterdam, the Netherlands and Amsterdam, the Netherlands [47] | Purpose: To analyze the development of anxiety and distress among men receiving AS. Setting: Rotterdam, the Netherlands and Amsterdam, the Netherlands. | Design: Quantitative, non-RCT. Methods: Questionnaires were mailed to the subjects and follow-up questionnaires were provided at 9 and 18 months. Statistics: Descriptives, Cronbach′s alpha, paired samples t-test, and a linear mixed model. Sample: 150 men invited and 129 participated. Response rate: Baseline 86%, 9 month 90%, and 18 month 96%. | Race/Ethnicity: Not indicated. | Reported Instruments: Distress was measured with the DCS, CES-D. General anxiety was measured through the STAI-6 and the MAX-PC measured PCa-specific anxiety. General physical health was assessed with SF-12. | Key Findings: Decreased anxiety and general anxiety and fear of disease progression, among low-risk PCa survivors receiving AS. | Strengths: Use of multiple measures for assessing anxiety and distress. Limitations: Baseline anxiety and distress scores not available, small sample size, and could not compare across time points due to the lack of baseline data. |

| Watts et al., (2015)/ South, Central and Western England [42] | Purpose: Assess the presence of anxiety and depression among men on AS. Setting: Secondary care prostate cancer (PCa) clinics across South, Central and Western England. | Design: Quantitative, Cross-sectional questionnaire survey. Methods: Participants from 7 sites were mailed the questionnaire. Statistics: Descriptives and logistic regression. Sample: 426 were invited and 313 participated. Response rate: 73.47%. | Race/Ethnicity: White: 302 Afro-Caribbean: 4 Asian: 3 Unknown: 3 Other: 1. | Reported instruments: Depression and anxiety was assessed by the HADS. | Key Findings: Higher rates of anxiety and depression among patients receiving AS than in the general population. | Strengths: Large multi-center examination of anxiety and depression among patients receiving AS. Limitations: Unable to establish causality of anxiety and depression in this population due to statistical methods. |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dickey, S.L.; Grayson, C.J. The Quality of Life among Men Receiving Active Surveillance for Prostate Cancer: An Integrative Review. Healthcare 2019, 7, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare7010014

Dickey SL, Grayson CJ. The Quality of Life among Men Receiving Active Surveillance for Prostate Cancer: An Integrative Review. Healthcare. 2019; 7(1):14. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare7010014

Chicago/Turabian StyleDickey, Sabrina L., and Ciara J. Grayson. 2019. "The Quality of Life among Men Receiving Active Surveillance for Prostate Cancer: An Integrative Review" Healthcare 7, no. 1: 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare7010014

APA StyleDickey, S. L., & Grayson, C. J. (2019). The Quality of Life among Men Receiving Active Surveillance for Prostate Cancer: An Integrative Review. Healthcare, 7(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare7010014