Postpartum Care Service Experience Model: A Case of Postpartum Home Visiting Services

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Studies on Postpartum Care

2.2. Consumer Experience

2.3. Experiential Value

2.4. Experience Satisfaction

3. Methods

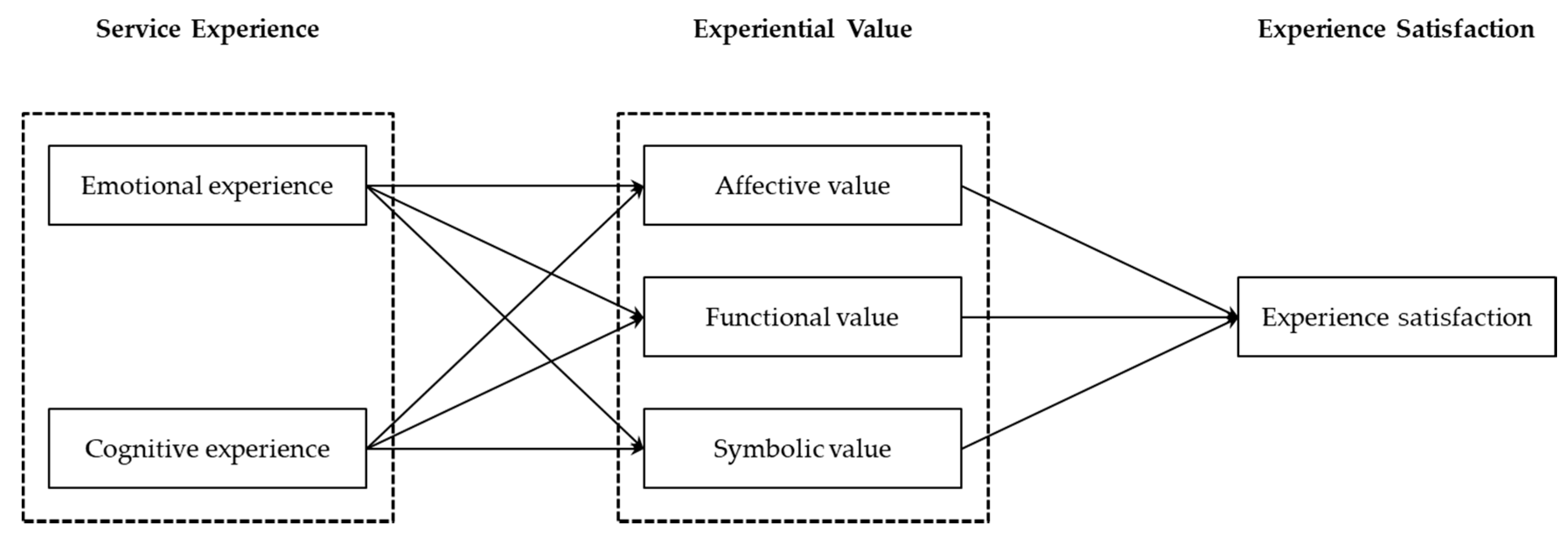

3.1. Research Framework

3.2. Operational Definitions of Research Variables

3.2.1. Service Experience

3.2.2. Experiential Value

3.2.3. Experience Satisfaction

3.3. Research Tools

3.3.1. Service Experience

3.3.2. Experiential Value

3.3.3. Experience Satisfaction

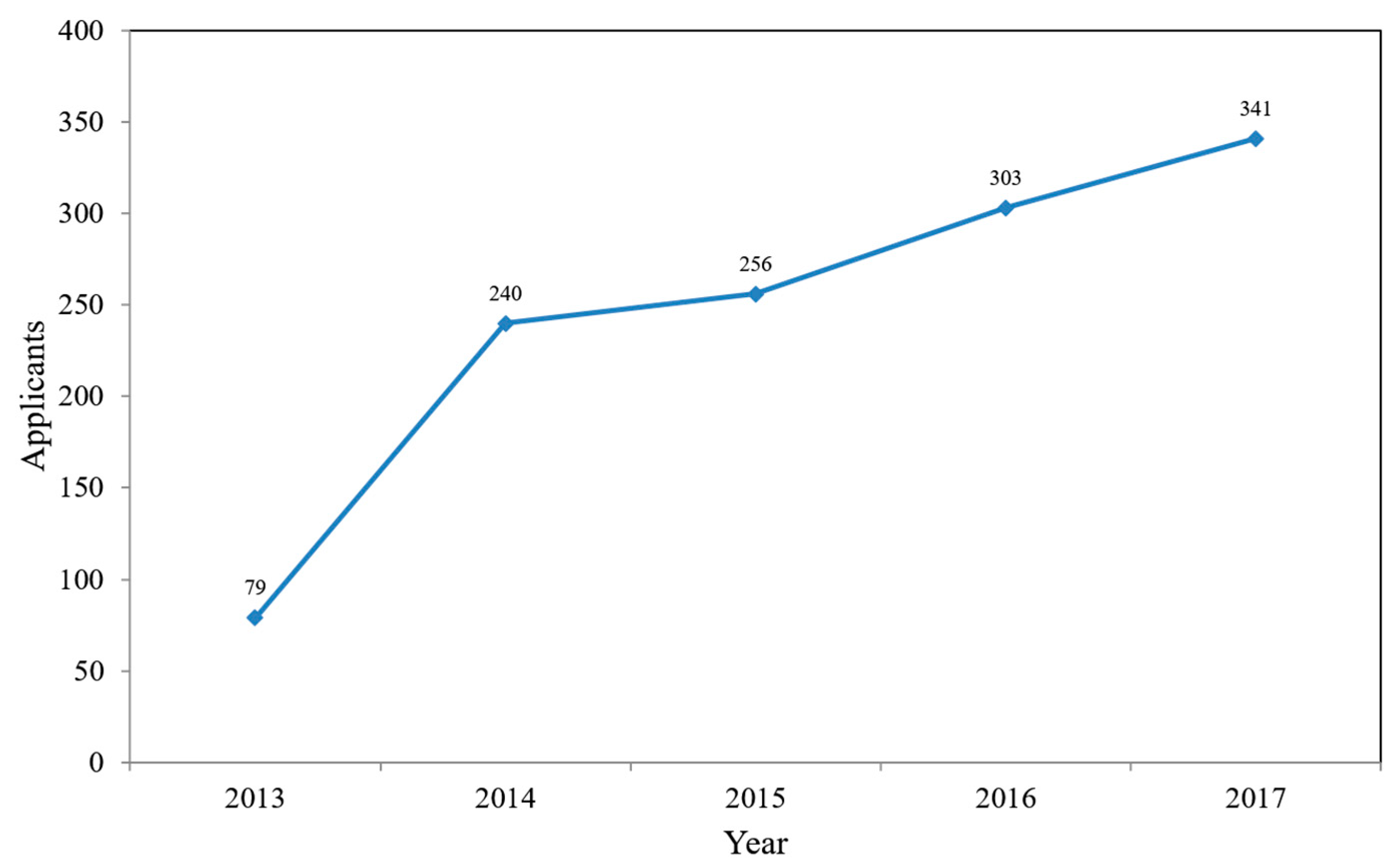

3.4. Participants

3.5. Research Process

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model Reliability and Validity Analysis

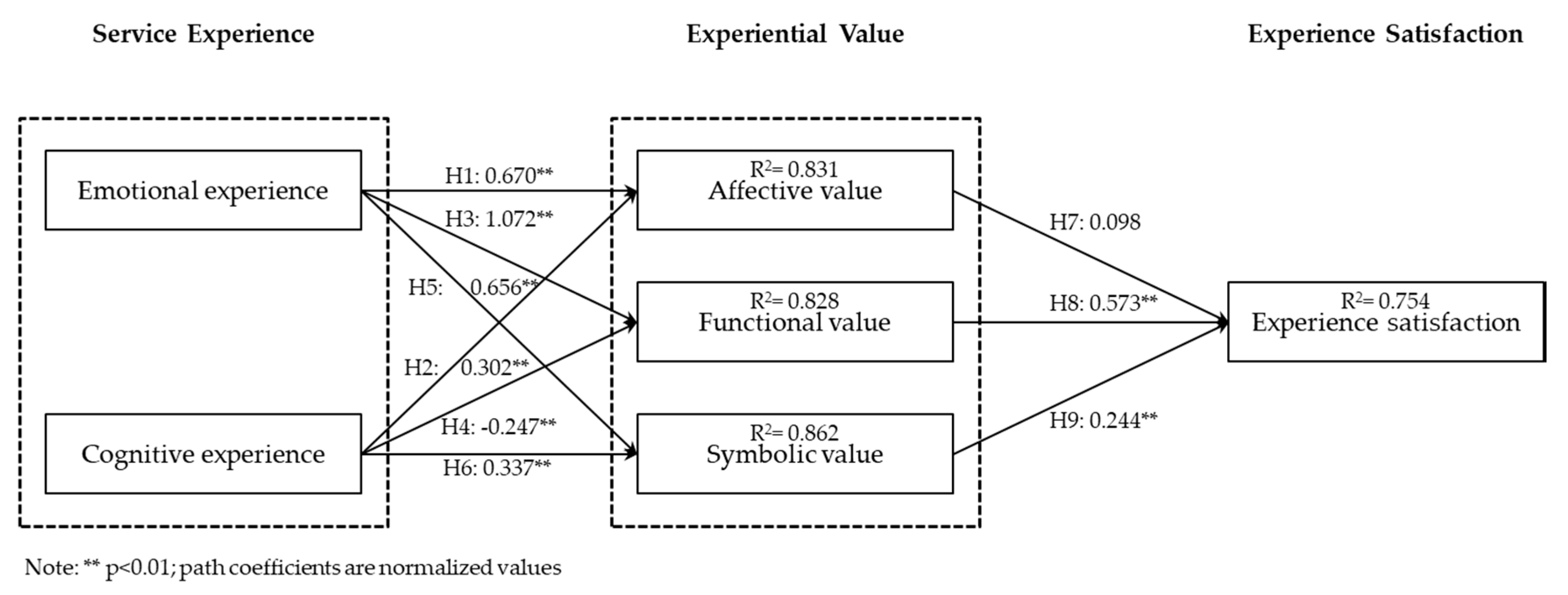

4.2. Hypothesis Tests

5. Conclusions and Suggestions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huang, K.-T. Using a Conjoint Analysis to Design Postpartum Rest Services for Postpartum Rest Center. Master’s Thesis, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, M. The Analysis of 4 Exchange Cost on Postnatal Confinement Center. Master’s Thesis, National Chengchi University, Taipei, Taiwan, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pine, B.J.; Gilmore, J.H. Welcome to the experience economy. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1998, 76, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schmitt, B. Experiential marketing. J. Mark. Manag. 1999, 15, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brakus, J. A Theory of Consumer Experiences. Ph.D. Thesis, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, Y.-C.; Su, T.-H.; Chang, Y.-F. An examination of the effects of patients’ received medical messages on the experiential module-a case study of local hospitals. J. Healthc. Manag. 2006, 7, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Su, T.-H. Medical service experience model for medical cosmetology. Manag. Rev. 2016, 35, 51–70. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.-C.; Chen, G.-L.; Zhao, Z.-Y. A study on blog browsing behavior from the experiential marketing perspective: An example of one million star. Manag. Rev. 2009, 28, 75–89. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.-H. The relationship between situational factors of fashion consumption and consumer experiences from the aspect of experiential marketing: An example on pleats please brand. Taiwan Text. Res. J. 2009, 19, 13–27. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, Y.-S.; Syu, S.-H. The relationship of experiential marketing, experiential value and revisiting willingness-an empirical study of regional hot spring. Bull. Natl. Pingtung Inst. Commer. 2013, 15, 287–316. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, C.-C.; Hsu, S.-F. A study of the relationship between experienced value and brand performance of gourmet restaurant customers in metro area of Taiwan. J. Commer. Mod. 2011, 6, 43–57. [Google Scholar]

- Sinha, I.; DeSarbo, W.S. An integrated approach toward the spatial modeling of perceived customer value. J. Mark. Res. 1998, 35, 236–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, M.B.; Hirschman, E.C. The experiential aspects of consumption: Consumer fantasies, feelings, and fun. J. Consum. Res. 1982, 9, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overby, J.W. The Impact of National Culture upon the Customer Value Hierarchy: A Comparison between French and American Consumers. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. WHO Technical Consultation on Postpartum and Postnatal Care; WHO_MPS_10.03; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tien, S.-F.; Yu, Y.-M.; Chen, Y.-C. Review of postpartum care studies 1970–2004. J. MacKay Nurs. 2007, 1, 6–13. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C. A study of pregnant women’s choice of the postpartum care center in Taiwan. J. Chin. Econ. Res. 2014, 12, 71–88. [Google Scholar]

- Su, S.; Hsiao, S.-H.; Tang, J.-Y. Quality of care in postpartum care organizations in Taipei. Taiwan J. Public Health 2002, 21, 266–277. [Google Scholar]

- Hori, N.; Liu, Y.-L.; Chen, H.-F. A study of relationship between the roles of postpartum care center and purchase intention- service expectation as a mediator. J. Tour. Leis. Manag. 2016, 4, 129–141. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, S.-H.; Tsai, C.-W.; Lee, W.-L. Doing the month service at home and service interaction-the study of relationship marketing. J. Tzu Chi Coll. Technol. 2014, 23, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschman, E.C.; Holbrook, M.B. Hedonic consumption: Emerging concepts, methods and propositions. J. Mark. 1982, 46, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rifkin, J. The Age of Access: The New Culture of Hypercapitalism; Penguin Putnam: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Carù, A.; Cova, B. Revisiting consumption experience: A more humble but complete view of the concept. Mark. Theory 2003, 3, 267–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.W.; Young, S.M. Consumer response to television commercials: The impact of involvement and background music on brand attitude formation. J. Mark. Res. 1986, 23, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, J.C.; Soutar, G.N. Consumer perceived value: The development of a multiple item scale. J. Retail. 2001, 77, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strahilevitz, M.; Myers, J.G. Donations to charity as purchase incentives: How well they work may depend on what you are trying to sell. J. Consum. Res. 1998, 24, 434–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardozo, R.N. An experimental study of customer effort, expectation, and satisfaction. J. Mark. Res. 1965, 2, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.-H.; Chang, H.-C.; Huang, G.-L. A study of service quality, customer satisfaction and loyalty in taiwanese leisure industry. J. Am. Acad. Bus. 2006, 9, 126–132. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, R.L. A cognitive model of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction decisions. J. Mark. Res. 1980, 17, 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodruff, R.B.; Cadotte, E.R.; Jenkins, R.L. Modeling consumer satisfaction processes using experience-based norms. J. Mark. Res. 1983, 20, 296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C. A national customer satisfaction barometer: The Swedish experience. J. Mark. 1992, 56, 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, C.; Mathews, B.P. Customer satisfaction: Contrasting academic and consumers’ interpretations. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2001, 19, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, K.; Martensen, A.; Gronholdt, L. Customer satisfaction measurement at post Denmark: Results of application of the European customer satisfaction index methodology. Total. Qual. Manag. 2000, 11, 1007–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breckler, S.J.; Wiggins, E.C. Cognitive responses in persuasion: Affective and evaluative determinants. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 27, 180–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, R.J. The effects of mood states on service contact strategies. J. Prof. Serv. Mark. 1996, 14, 117–135. [Google Scholar]

- Petty, R.E.; Cacioppo, J.T. Source factors and the elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. Adv. Consum. Res. 1984, 11, 668–672. [Google Scholar]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Will, A. SmartPLS 2.0. Hamburg. Available online: http://www.smartpls.de (accessed on 18 March 2013).

- Comrey, A.L.; Lee, H.B. A First Course in Factor Analysis, 2nd ed.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W.; Newsted, P.R. Structural equation modeling analysis with small samples using partial least squares. In Statistical Strategies for Small Sample Research; Hoyle, R.H., Ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1999; Volume 1, pp. 307–341. [Google Scholar]

- Zlotnick, C.; Johnson, S.L.; Miller, I.W.; Pearlstein, T.; Howard, M. Postpartum depression in women receiving public assistance: Pilot study of an interpersonal-therapy-oriented group intervention. Am. J. Psychiatry 2001, 158, 638–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Operational Definition | References |

|---|---|---|

| Emotional experience | Internal feelings and emotions of target service users, which are affected by the service context and postpartum service personnel. | Breckler and Wiggins [34]; Schmitt [4]; Schultz [35]. |

| Cognitive experience | Target service users require sufficient amount of information to rationally evaluate service benefits. | Petty and Cacioppo [36]; Schmitt [4]. |

| Research Variable | Observed Variable | Mean | Std. | Factor Loading | Composite Reliability | AVE | Cronbach Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional experience | Your satisfaction with attendant care | 3.51 | 0.63 | 0.82 | 0.90 | 0.76 | 0.84 |

| The personnel can provide active and positive interaction | 3.67 | 0.61 | 0.90 | ||||

| The personnel is patient, considerate, and careful in her/his work | 3.65 | 0.57 | 0.89 | ||||

| Cognitive experience | Your satisfaction with the personnel’s daily record content | 3.44 | 0.59 | 0.91 | 0.82 | 0.70 | 0.58 |

| Your satisfaction with the content of the postpartum care contract | 3.23 | 0.65 | 0.75 | ||||

| Affective value | If you have a question, the personnel can immediately give a clear reply | 3.60 | 0.54 | 0.86 | 0.94 | 0.83 | 0.90 |

| Your satisfaction with the personnel’s attitude toward postpartum care | 3.60 | 0.58 | 0.96 | ||||

| The personnel is responsible in each task | 3.47 | 0.63 | 0.91 | ||||

| Functional value | I like the food provided by the personnel | 3.40 | 0.66 | 0.86 | 0.88 | 0.65 | 0.82 |

| The personnel is good at house chores | 3.19 | 0.66 | 0.82 | ||||

| Newborn care provided by the personnel is professional | 3.63 | 0.58 | 0.79 | ||||

| The personnel’s observation of child behavior and development is professional | 3.72 | 0.50 | 0.75 | ||||

| Symbolic value | Family members’ attitudes toward the personnel’s assistance at home | 3.58 | 0.63 | 0.93 | 0.94 | 0.88 | 0.86 |

| Overall experience of postpartum care provided by the personnel | 3.53 | 0.63 | 0.95 | ||||

| Satisfaction | Satisfaction with the overall service provided by the personnel | 3.47 | 0.63 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Functional Value | Cognitive Experience | Affective Value | Emotional Experience | Symbolic Value | Experience Satisfaction | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Functional Value | 0.88 | |||||

| Cognitive Experience | 0.53 | 0.82 | ||||

| Affective Value | 0.78 | 0.78 | 0.94 | |||

| Emotional Experience | 0.89 | 0.72 | 0.89 | 0.90 | ||

| Symbolic Value | 0.80 | 0.81 | 0.91 | 0.90 | 0.94 | |

| Experience Satisfaction | 0.85 | 0.62 | 0.77 | 0.82 | 0.79 | 1 |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chang, P.-P. Postpartum Care Service Experience Model: A Case of Postpartum Home Visiting Services. Healthcare 2018, 6, 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare6030091

Chang P-P. Postpartum Care Service Experience Model: A Case of Postpartum Home Visiting Services. Healthcare. 2018; 6(3):91. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare6030091

Chicago/Turabian StyleChang, Pei-Ping. 2018. "Postpartum Care Service Experience Model: A Case of Postpartum Home Visiting Services" Healthcare 6, no. 3: 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare6030091

APA StyleChang, P.-P. (2018). Postpartum Care Service Experience Model: A Case of Postpartum Home Visiting Services. Healthcare, 6(3), 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare6030091