The Patient Experience: Informing Practice through Identification of Meaningful Communication from the Patient’s Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

- Cinahl plus with full text (hits = 46)

- BMJ Journals online (hits = 47)

- Cochrane Library (hits = 69)

- Medline (hits = 3)

- Pro Quest Nursing and Allied Health Source (hits = 300)

- RCN Journal (hits = 35)

- Wiley online library (hits = 38)

- Google Scholar (hits = 96)

3. Methods

3.1. Aims

- (1)

- Examine the issues that influence the effectiveness of communication on patient satisfaction, experience and engagement, in an acute National Health Service setting, through identification of the patient’s requirements and expectations.

- (2)

- Explore the attributes of meaningful communication in an acute healthcare setting from the patient’s perspective.

3.2. Design

3.3. Sample and Settings

3.4. Ethics

3.5. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. The Friends and Family Test (FFT) Survey Results

4.2. The Friends and Family Test (FFT) Narrative Analysis

4.3. The Communication Survey Results

4.4. The Communication Survey Narrative Analysis

- 21 patients suggested that more staff were needed on the wards as they felt that the staff caring for them were too busy.

- 42 patients felt there was too little or inconsistent communication about their condition and/or hospital stay

- 22 patients described frustrations with delays resulting in a longer hospital stay after they had been told they could go home.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

7. Implications for Practice

- Developing an inpatient leaflet which explains the concept of shared decision making and why it is important. Provides an explanation that their knowledge about their health and lifestyle is as important as the clinician’s expertise with each complimenting each other.

- Creating a communication drive to encourage patients to ask questions providing suggested questions as examples on electronic posters, notice boards and hospital websites

- Introducing a paper at the bedside for question prompt lists to enable questions to be written down as the patient and/or relative thinks of them in preparation of ward rounds

- Exploring the use of the internet as a patient information tool to generate questions.

- Supporting clinicians to improve their communication skills—Develop a training programme for introduction of “teach back” methodology

- Promoting extended visiting hours to support more opportunity for communication.

- Ensure patient information leaflets are written to the recommended reading age to facilitate understanding by the majority of the population.

8. Recommendations for Future Evaluations/Research

- Conduct the evaluation for planned and emergency admissions separately to identify if there are any variances in results

- Repeat at ward level to identify examples of good practice for dissemination across the organisation

- Repeat with inclusion of demographic detail to identify if there are any variances in results.

- Repeat for individual demographic patient groups to identify specific communication strategies and needs.

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wiig, S.; Storm, M.; Aase, K.; Gjestsen, M.; Solhelm, M.; Harthug, S.; Robert, G.; Fulop, N. QUASER Team. Investigating the use of patient involvement and patient experience in quality improvement in Norway: Rhetoric or reality? BMC Health Serv. Res. 2013, 13, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, F.; Burt, J.; Roland, M. Measuring Patient Experience: Concepts and Methods. Patient 2014, 7, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, R.; Elliott, M.; Zaslavsky, A.; Hays, R.; Lehrman, W.; Rybowski, L.; Edgman-Levitan, S.; Clearly, P. Examining the role of patient experience surveys in measuring healthcare quality. Med. Care Res. Rev. 2014, 71, 522–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juve-Udina, M.; Perez, E.; Padres, N.; Samartino, M.; Garcia, M.; Creus, M.; Batilori, N.; Calvo, C. Basic Nursing Care: Retrospective evaluation of communication and psychosocial interventions documented by nurses in the acute care setting. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2014, 46, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snellman, I.; Gustafsson, C.; Gustafsson, L. Patients’ and Caregivers’ Attributes in a Meaningful Care Encounter: Similarities and Notable Differences. Int. Sch. Res. Netw. Nurs. 2012, 2012, 320145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Gustafsson, C.; Gustafsson, L.; Snellman, I. Trust leading to hope—The signification of meaningful encounters in Swedish healthcare. The narratives of patients, relatives and healthcare staff. Int. Pract. Dev. J. 2013, 3, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Newell, S.; Jordan, Z. The patient experience of patient-centred communication with nurses in the hospital setting: A qualitative systematic review protocol. JBI Database Syst. Rev. Implement. Rep. 2015, 13, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Entwistle, V.; Firnigl, D.; Ryan, M.; Francis, J.; Kinghorn, P. Which experiences of healthcare delivery matter to service users and why? A critical interpretive synthesis and conceptual map. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2012, 17, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foot, C.; Gilbert, H.; Dunn, P.; Jabbal, J.; Seale, B.; Goodrich, J.; Buck, D.; Taylor, J. People in Control of Their Own Health and Care: The State of Involvement; The Kings Fund: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health. Liberating the NHS: No Decision About Me Without Me; The Stationary Office: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, R. Report of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Inquiry: Executive Summary; The Stationary Office: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Keogh, B. Review into the Quality of Care and Treatment Provided by 14 Hospital Trusts In England: Overview Report. 2013. Available online: http://www.nhs.uk/nhsengland/bruce-keogh-review/documents/outcomes/keogh-review-final-report.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2018).

- Care Quality Commission. Adult Inpatient Survey. 2015. Available online: http://www.cqc.org.uk/content/adult-inpatient-survey-2015 (accessed on 1 February 2018).

- Ponsignon, F.; Smart, A.; Williams, M.; Hall, J. Healthcare experience quality: An empirical exploration using content analysis techniques. J. Serv. Manag. 2015, 26, 460–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredericks, S.; Lapum, J.; Hui, G. Examining the effect of patient-centred care on outcomes. Br. J. Nurs. 2015, 24, 394–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levinson, W.; Hudak, P.; Tricco, A. A systematic review of surgeon-patient communication: Strengths and opportunities for improvement. Patient Educ. Couns. 2013, 93, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mortensen, D. Communication: The Study of Human Interaction; McGraw-Hill Book Company: New York, NY, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Legg, A.; Andrews, S.; Huynh, H.; Ghane, A.; Tabuenca, A.; Sweeny, K. Patients’ anxiety and hope: Predictors and adherence intensions in an acute care context. Health Expect. 2014, 18, 3034–3043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saunders, C.; Abel, G.; Lyratzopoulos, G. What explains worse patient experience in London? Evidence from secondary analysis of the cancer patient experience survey. BMJ Open 2014, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Department of Health. High Quality Care for All: NHS Next Stage Review Final Report; The Stationary Office: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health & NHS Midlands and East. NHS Friends and Family Test Implementation Guidance. 2012. Available online: http://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/fft-imp-guid.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2018).

- Reeves, R.; West, E.; Barron, D. Facilitated patient experience feedback can improve nursing care: A pilot study for a phase III cluster randomised controlled trial. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2013, 13, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, C.; McCormick, S. Overarching Questions for Patient Surveys: Development Report for the Care Quality Commission; National Patient Survey Coordination Centre: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dawood, M.; Gallini, A. Using discovery interviews to understand the patient experience. Nurs. Manag. 2010, 17, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manacorda, T.; Erens, B.; Black, N.; Mays, N. The Friends and Family Test in General Practice in England: A qualitative study of the views of staff and patients. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2017, 67, 370–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picker Institute Europe. Policy Briefing: The Friends and Family Test; Picker Institute Europe: Oxford, MI, USA, August 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lynn, P. The Friends and Family Test Is Unfit for Purpose. The Guardian, 2013. Available online: http://www.theguardian.com/healthcare-network/2013/apr/09/friends-family-test-unfit-forpurpose (accessed on 1 February 2018).

- Reeves, R. Why the Friends and Family Test Won’t Work. Health Serv. J. 2012. Available online: http://www.hsj.co.uk/comment/columnists/why-the-friends-and-family-testwont-work/5052423.article (accessed on 1 February 2018).

- Sizmur, S.; Graham, C.; Walsh, J. Influence of patients’ age and sex and the mode of administration on results from the NHS Friends and Family Test of patient experience. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2014, 20, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, C. The Friends and Family Test Can Make the Grade. Health Serv. J. 2013. Available online: http://www.hsj.co.uk/comment/the-friends-andfamily-test-can-make-thegrade/5062422.article (accessed on 1 February 2018).

- Lemke, F.; Clark, M.; Wilson, H. Customer experience quality: An exploration in business and consumer contexts using repertory grid technique. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2011, 39, 846–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, L.; Petersen, A.; Johnsen, A.; Lundstrom, L.; Groenvold, M. Cancer patients’ evaluation of communication: A report from the population based study “The Cancer Patient’s World”. Support. Care Cancer 2013, 21, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjertnaes, O.; Sjetne, I.; Iversen, H. Overall patient satisfaction with hospitals: Effects of patient reported experiences and fulfilment of expectations. Br. Med. J. Qual. Saf. 2012, 21, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dicks, S.; Chaplin, R.; Hood, C. Factors affecting care on acute hospital wards. Nurs. Older People 2013, 25, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinagre, M.; Neves, J. The influence of service quality and patients’ emotions on satisfaction. Int. J. Health Care Qual. Assur. 2008, 21, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otani, K.; Waterman, B.; Claiborne, W.; Ehinger, S. Patient satisfaction: How patient health conditions influence their satisfaction. J. Healthc. Manag. 2012, 57, 276–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palese, A.; Tornietto, M.; Suhonen, R.; Efstathiou, G.; Tsangari, H.; Merkouris, A.; Jarosova, D.; Leino-Kilpi, H.; Patiraki, E.; Kariou, C.; et al. Surgical patient satisfaction as an outcome of nurses’ caring behaviours: A descriptive and correlational study in six European countries. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2011, 43, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaVela, S.L.; Gallan, A.S. Evaluation and Measurement of Patient Experience. Patient Exp. J. 2014, 1, 28–36. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Abri, R.; Al-Balushi, A. Patient Satisfaction Survey as a Tool towards Quality Improvement. Oman Med. J. 2014, 29, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hart, C. Doing Your Masters Dissertation; Sage Publications Limited: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Deviant, S. The Practically Cheating Statistics Handbook, 2nd ed.; The Sequel; Andale LLC: Orlando, FL, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- NHS England. Organisational Level Tables (Historic). FFT Inpatient—September 2015. 2015. Available online: https://www.england.nhs.uk/ourwork/pe/fft/friends-and-family-test-data/fft-data-historic/ (accessed on 1 February 2018).

- Coulter, A.; Fitzpatrick, R.; Cornwell, J. The Point of Care. Measures of Patients’ Experience in Hospital: Purpose, Methods and Uses; The Kings Fund: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Angus, D.; Watson, B.; Smith, A.; Gallois, C.; Wiles, J. Visualising Conversation Structure across Time: Insights into Effective Doctor-Patient Consultations. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e38014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGilton, K.; Boscart, V.; Fox, M.; Sidani, S.; Rochon, E.; Sorin-Peters, R. A Systematic Review of the Effectiveness of Communication Interventions for Health Care Providers Caring for Patients in a Residential Setting. World Views Evid. Based Nurs. 2009, 6, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission. Eurobarometer Qualitative Study: Patient Involvement. Aggregate Report. May 2012. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/quali/ql_5937_patient_en.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2018).

- Joseph-Williams, N.; Edwards, A.; Elwyn, A. Power imbalance prevents shared decision making. Br. Med. J. 2014, 348, g3178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Legare, F.; Shemilt, M.; Stacey, D. Can Shared Decision Making Increase the Uptake of Evidence Based Practice? Frontline Gastroenterol. 2011, 2, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grossman, V. Hot topics: Do we make the difficult patient more difficult? J. Radiol. Nurs. 2012, 31, 27–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judson, T.; Detsky, A.; Press, M. Encouraging Patients to Ask Questions. How to Overcome “White-Coat Silence”. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2013, 309, 2325–2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahedi, F. The challenge of truth telling across cultures: A case study. J. Med. Ethics Hist. Med. 2011, 4, 11. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- NHS England. Accessible Information Standard. Making Health and Social Care Information Accessible. 2016. Available online: https://www.england.nhs.uk/ourwork/accessibleinfo/ (accessed on 1 February 2018).

| 1 | How likely are you to recommend our ward to your family and friends if they need similar care or treatment? | Extremely likely | Likely | Neither likely nor unlikely | Extremely unlikely | Don’t know | Comments |

| 1151 | 261 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 0 | ||

| 2 | Do you feel your pain was kept under control? | Yes always | Yes sometimes | Not at all | Never had pain | Comments | |

| 1166 | 150 | 9 | 119 | 0 | |||

| 3 | Do you feel your privacy and dignity were respected? | All of the time | Most of the time | Some of the time | None of the time | Comments | |

| 1328 | 92 | 22 | 2 | 0 | |||

| 4 | Did you get enough help from staff to eat your meals? | Yes always | Yes sometimes | Not at all | Did not need help | Comments | |

| 761 | 45 | 7 | 630 | 0 | |||

| 5 | Were you involved as much as you wanted to be in decisions about your care and treatment? | Yes | Most of the time | Sometimes | Never | Not applicable | Comments |

| 1195 | 177 | 57 | 9 | 5 | 0 | ||

| 6 | Did you feel that you were treated with compassion? | All of the time | Most of the time | Some of the time | None of the time | Not applicable | Comments |

| 1285 | 122 | 23 | 1 | 13 | 0 | ||

| 7 | Did you feel you were involved in decisions about you discharge from hospital? | Yes definitely | Yes, to some extent | No | I did not need to be involved | Not applicable | |

| 1065 | 248 | 41 | 26 | 64 | 0 | ||

| 8 | Were you given enough notice about when you were going to be discharged? | Yes definitely | Yes, to some extent | No | Not applicable | ||

| 1086 | 241 | 34 | 80 | 0 | |||

| 9 | What was the best thing about your experience today? | Comments | |||||

| 584 | |||||||

| 10 | What one thing could we have done better? | Comments | |||||

| 169 | |||||||

| The following link provides all the information and guidance about the Friends and Family Test https://www.england.nhs.uk/fft/ | |||||||

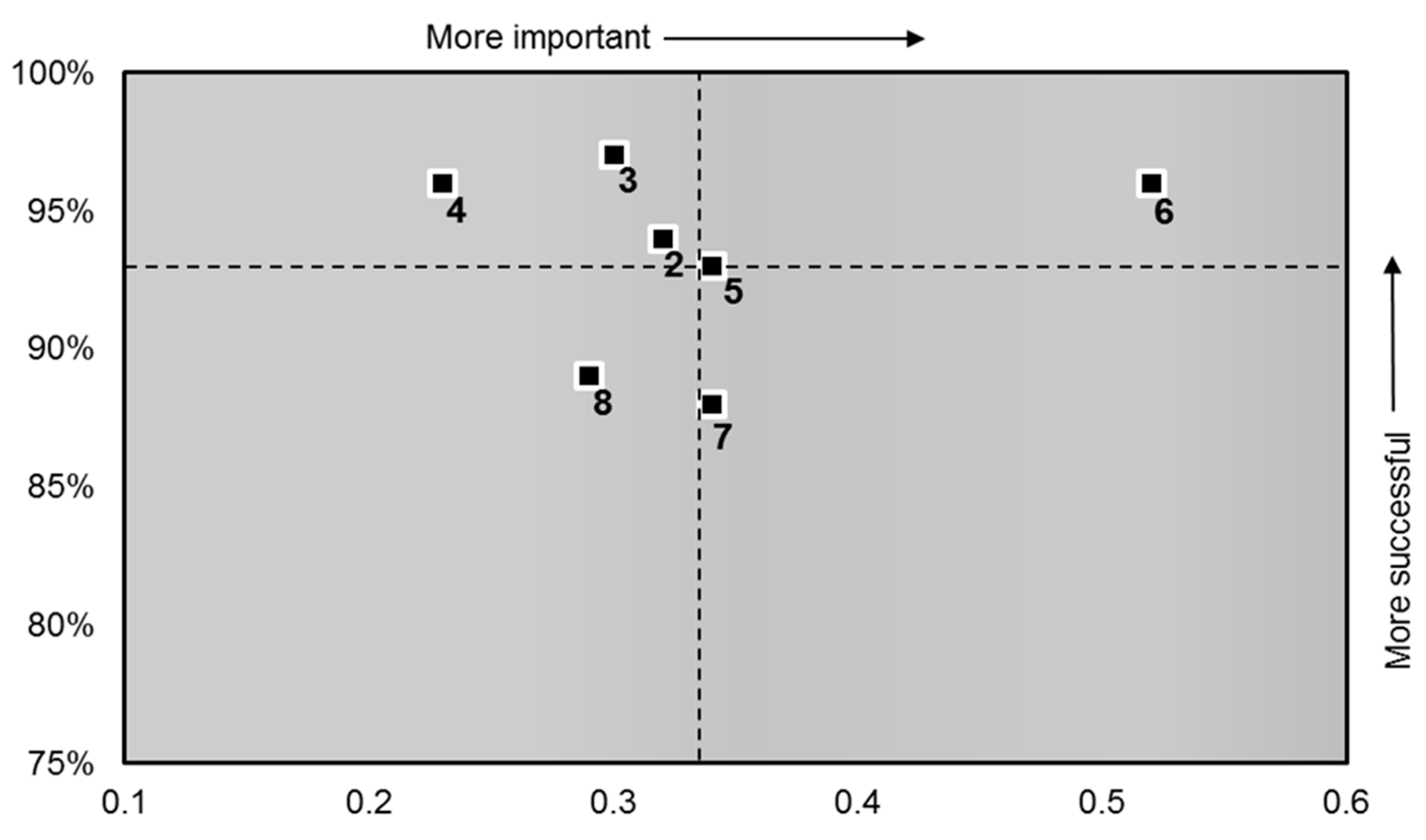

| Question Number | Question in Order of Importance | Score | Importance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | Did you feel you were treated with compassion? | 96.08 | 0.52 |

| 7 | Did you feel you were involved in decisions about your discharge from hospital? | 87.82 | 0.34 |

| 5 | Were you involved as much as you wanted to be in decisions about your care and treatment? | 92.69 | 0.34 |

| 2 | Do you feel your pain was kept under control? | 93.65 | 0.32 |

| 3 | Do you feel your privacy and dignity were respected? | 96.75 | 0.30 |

| 8 | Were you given enough notice about when you were going to be discharged? | 88.73 | 0.29 |

| 4 | Did you get enough help from staff to eat your meals? | 96.36 | 0.23 |

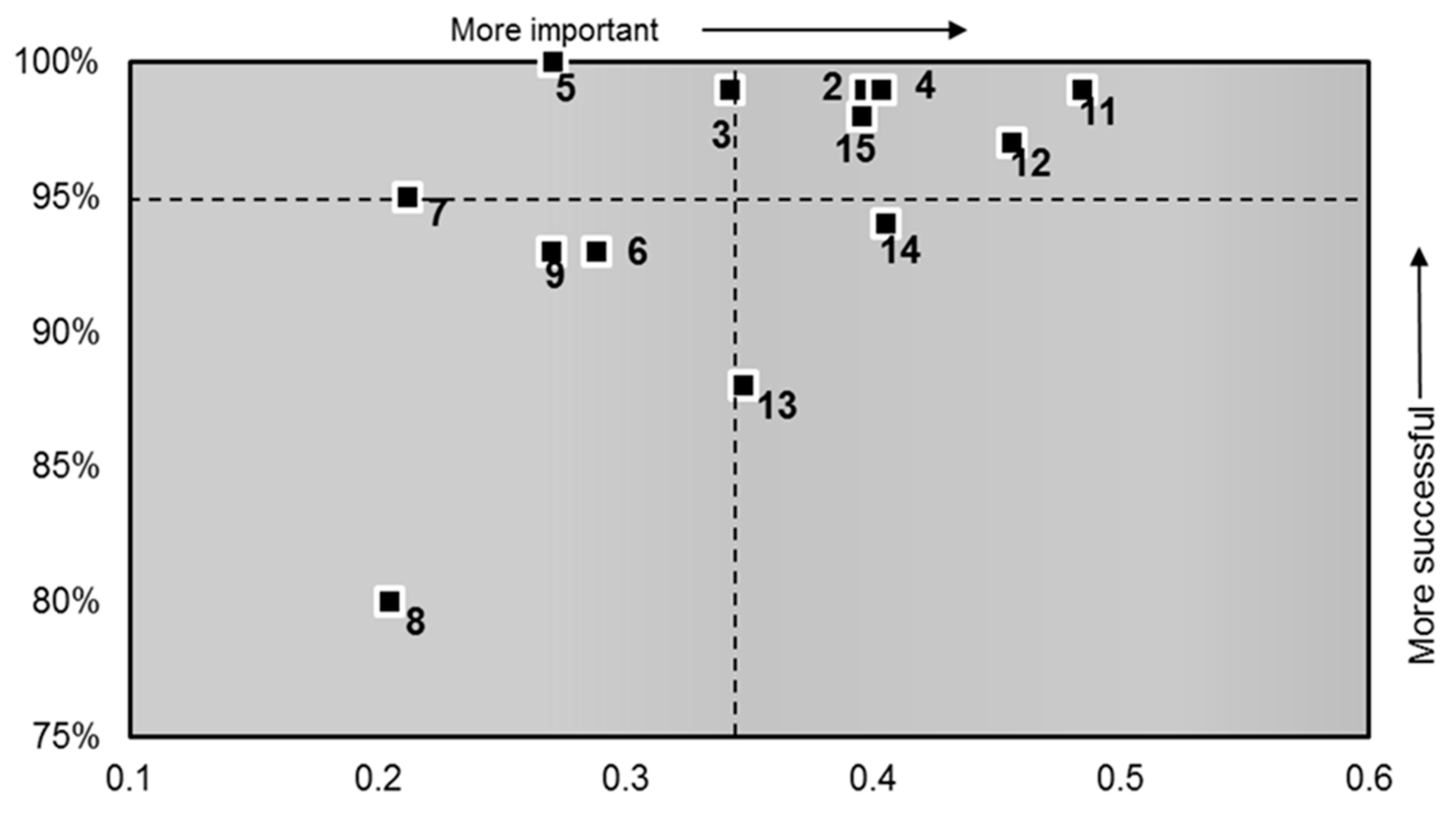

| Question Number | Question in Order of Importance (Patient to Staff) | Score | Importance (r) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11 | How much information about your condition or treatment has been given to you? | 99% | 0.48 |

| 12 | Has a member of staff answered your questions about the operation or procedure? (if applicable) | 97% | 0.46 |

| 14 | Afterwards, did a member of staff explain the operation or procedure? (if applicable) | 94% | 0.41 |

| 4 | Did you have confidence and trust in the doctors treating you? | 99% | 0.40 |

| 2 | When you have important questions to ask a doctor do you get answers that you can understand? | 99% | 0.40 |

| 15 | Do you feel you were given enough privacy when discussing your condition or treatment? | 98% | 0.40 |

| 13 | Have you been told how you will feel after you had the operation or procedure? (if applicable) | 88% | 0.35 |

| 3 | When you have important questions to ask a nurse do you get answers that you can understand? | 99% | 0.34 |

| 6 | Do doctors talk in front of you as if you weren’t there? | 93% | 0.29 |

| 5 | Did you have confidence and trust in the nurses treating you? | 100% | 0.27 |

| 9 | Does one member of staff say one thing and another say something different regarding your care? | 93% | 0.27 |

| 7 | Do nurses talk in front of you as if you weren’t there? | 95% | 0.21 |

| 8 | In your opinion, are there enough nurses on duty to care for you in hospital? | 80% | 0.20 |

| Word | Word Count | Average Score | Negative Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discharge | 17 | 82.86% | 15 |

| Waiting | 7 | 82.36% | 7 |

| Communication | 11 | 81.74% | 8 |

| Night | 15 | 70.34% | 10 |

| Attribute | Word Count | Average Score |

|---|---|---|

| Professional | 23 | 98.40% |

| Kind | 28 | 95.99% |

| Friendly | 61 | 95.41% |

| Caring | 65 | 95.22% |

| Helpful | 61 | 94.58% |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Grocott, A.; McSherry, W. The Patient Experience: Informing Practice through Identification of Meaningful Communication from the Patient’s Perspective. Healthcare 2018, 6, 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare6010026

Grocott A, McSherry W. The Patient Experience: Informing Practice through Identification of Meaningful Communication from the Patient’s Perspective. Healthcare. 2018; 6(1):26. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare6010026

Chicago/Turabian StyleGrocott, Angela, and Wilfred McSherry. 2018. "The Patient Experience: Informing Practice through Identification of Meaningful Communication from the Patient’s Perspective" Healthcare 6, no. 1: 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare6010026

APA StyleGrocott, A., & McSherry, W. (2018). The Patient Experience: Informing Practice through Identification of Meaningful Communication from the Patient’s Perspective. Healthcare, 6(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare6010026