Nurse Perceptions of Artists as Collaborators in Interprofessional Care Teams

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Interprofessionalism in Healthcare

1.2. Arts in Health

1.3. Impacts and Outcomes of Arts in Health

1.4. The Arts and Interprofessionalism in Healthcare

1.5. Medical Perspective

1.6. Nursing Perspective

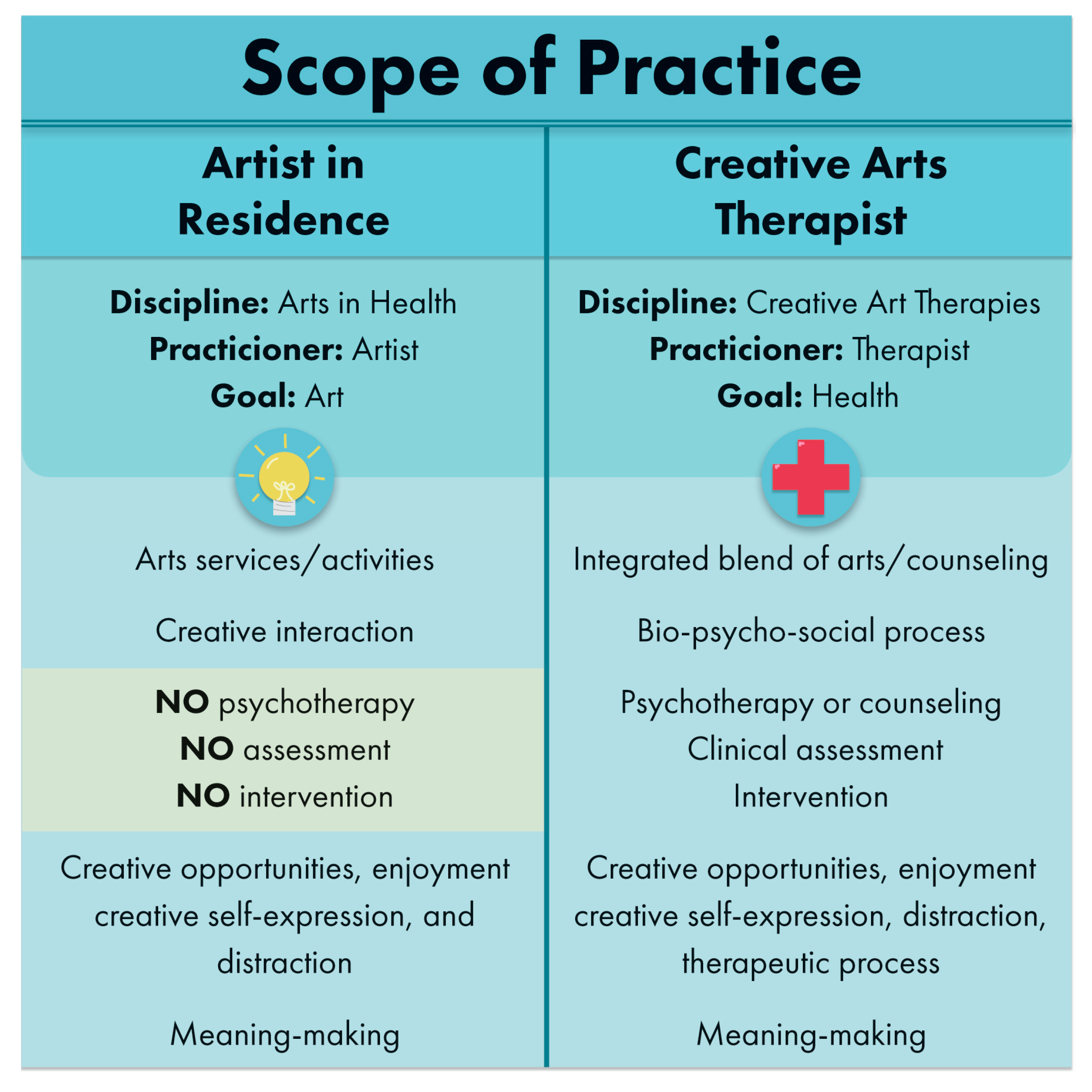

1.7. Creative Arts Therapies Perspective

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Domain 1: Values and Ethics

“I find it helpful and I don't think it should ever stop!”

“I just appreciate what they do, and… this is a tough floor to work on because there’s a lot of total care patients.”

“If a patient is happy, they're going to heal faster. I feel like it works”.

“…you have a resource here when you feel like the patient needs a different therapeutic outlet, that you have something that you can turn to.”

“I feel that I have other resources I can call on, when I have patients that need distraction, need something other than just nursing care.”

3.2. Domain 2: Roles/Responsibilities

“They do what we can’t.”

“It makes you more aware of other ways that you can be more creative in how you're impacting the care that you're giving the patient.”

“I think it gives me an alternative where if I know someone's bored, and they do want to do some drawing or painting, that I have an option.”

“I think it’s a help to the patient, especially with pain. It takes the patients’ minds off the pain and focuses it on other things”.

“If they’re busy doing something, it’s better than giving them medication. A lot of [patients] just need some diversion.”

“If you see your patient happy and they’re satisfied with what you’re giving them plus the arts in medicine helping us, it's a great feeling”.

“I feel that I have other resources I can call on, when I have patients that need distraction, need something other than just nursing care.”

“We don't have the resource, but Arts in Medicine has the resource and they provide it to the patient. I think it’s a help to the patient, especially with pain”.

“Having that additional resource here, it's always helpful to the nurses.”

“It makes me more calm and I don’t get as worked up.”

“I know that [the nurses] like to hear [the music] because there's a lot of stress on the floor and it's nice to listen to [it]. I love that personally. It helps relax [us].”

“I love the artists. It helps me have a better day—especially when they come around with the flute and I mean it's therapy for me, I feel like, just as much as the patient.”

“It’s someone else that is an advocate for [the patient].”

“It reminds me that we are not just here to take care of the patients physical needs. They also have emotional needs. It reminds me that these patients need a little bit of that too.”

“I think it's just a very positive thing for the patients. [The presence of the artist] lets the patients know that we care for them and that she’s got something for them to do.”

“I think it's a better quality of care because, like I said, the patients are more relaxed”.

“… it helps alleviate some of the worry, you know, ‘well what can I do to entertain this patient’? Because I can't always entertain them all the time, so it helps to have them distracted by something else.”

“It's something to do to divert their pain. It helps me. And you know, you don’t have to give them pain medication”.

3.3. Domain 4: Teams and Teamwork

“It can help entertain them, distract them, and re-direct them. So it assists me that way because someone else is spending that one on one time with them.”

“It takes the patients’ minds off of the pain and focuses it on other things. They’re able to relax which allows us to be able to relax because they're focused on other things. So it helps us.”

“It helps me because if they come in there, especially if my patients are in pain, and they come in, and they do an activity… We don't get to do that, like personal [attention] as a nurse, we don't get to do that much with the patients.”

“It is an excellent help. In pain, of course you don't want to be like… you can always bring them pain medication. But some of them just need some diversion. That’s the thing, they keep on watching the clock, but if they’re busy doing something, it’s better than giving them medication. A lot of them just need some diversion.”

“It's integrated into how I work”.

“It helps me to be creative and resourceful.”

“It makes you more aware of other ways how you can be more creative in how you're impacting the care that you're giving the patient.

3.4. Domain 5: Quality of Care

“I think it's a better quality of care because, like I said, the patients are more relaxed.”

“[The arts] create a more joyful, positive, homey feel for [patients]. They are happier to be here than when there weren't extra activities around for them.”

“I think it's improved [the quality of care]. We know [the art program] is there, we're more likely to recommend or try to seek it out, knowing that it's available.”

“I think with [the art program], [the unit] gives excellent care for the patient”.

“I think [with arts in medicine] it's a better quality of care.”

“Oh my God, it really has relieved my stress. It has. It’s great.”

“It makes me love being here and working with my patients. It really does. It has a big impact.”

3.5. Happy Patient/Happy Staff Effect

“I think it raises the morale of the patients. As long as we have happy patients, the staff will be happy.”

“It makes me relax as well. If I see my patient relaxed and not stressed, it makes me happy and relaxed in my 12-h shift. Indirect effect. If I have happy patients and they’re not stressed out for the whole day, then it makes me happy. Kind of fulfillment for the whole 12-h shift, because you know that's a long shift so if you see your patient happy and they’re satisfied with what you’re giving them, plus arts in medicine helping us, it's a great feeling.”

“It does make my job easier if they're less cranky.”

“It takes the patients’ minds off of the pain and focuses it on other things. They’re able to relax, which allows us to be able to relax because they're focused on other things.”

“When you support a patient, you’re supporting the staff.”

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barr, H.; Koppel, I.; Reeves, S.; Hammick, M.; Freeth, D.S. Effective Interprofessional Education: Argument. Assumption, and Evidence; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ødegård, A. Exploring perceptions of interprofessional collaboration in child mental health care. Int. J. Integr. Care 2006, 6, e25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Framework for Action on Interprofessional Education & Collaborative Practice; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite, J.; Westbrook, M.; Nugus, P.; Greenfield, D.; Travaglia, J.; Runciman, W.; Westbrook, J. Continuing differences between health professions‘ attitudes: The saga of accomplishing systems-wide interprofessionalism. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2012, 25, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel. Core Competencies for Interprofessional Collaborative Practice Report of an Expert Panel Interprofessional Education Collaborative; Interprofessional Education Collaborative Panel: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap, R.; Dunlap, A. Character ethics and interprofessional practice: Description and analysis. J. Interprof. Educ. Pract. 2017, 7, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proudfoot, J.; Jayasinghe, U.W.; Holton, C.; Grimm, J.; Bubner, T.; Amoroso, C.; Harris, M.F. Team climate for innovation: What difference does it make in general practice? Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velji, K.; Baker, G.R.; Fancott, C.; Andreoli, A.; Boaro, N.; Tardif, G.; Sinclair, L. Effectiveness of an adapted sbar communication tool for a rehabilitation setting. Healthc. Q. 2008, 11, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strasser, D.C.; Falconer, J.A.; Stevens, A.B.; Uomoto, J.M.; Herrin, J.; Bowen, S.E.; Burridge, A.B. Team training and stroke rehabilitation outcomes: A cluster randomized trial. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2008, 89, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knaus, W.A.; Draper, E.A.; Wagner, D.P.; Zimmerman, J.E. An evaluation of outcome from intensive care in major medical centers. Ann. Intern. Med. 1986, 104, 410–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pullon, S.; Morgan, S.; Macdonald, L.; McKinlay, E.; Gray, B. Observation of interprofessional collaboration in primary care practice: A multiple case study. J. Interprof. Care 2016, 30, 787–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zwarenstein, M.; Goldman, J.; Reeves, S. Interprofessional collaboration: Effects of practice-based interventions on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2009, 8, CD000072. [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster, G.; Kolakowsky-Hayner, S.; Kovacich, J.; Greer-Williams, N. Interdisciplinary communication and collaboration among physicians, nurses, and unlicensed assistive personnel. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2015, 47, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aston, J.; Shi, E.; Bullôt, H.; Galway, R.; Crisp, J. Qualitative evaluation of regular morning meetings aimed at improving interdisciplinary communication and patient outcomes. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2005, 11, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- State of the Field Committee. State of the Field Report: Arts in Healthcare 2009; Society for the Arts in Healthcare: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wreford, G. The state of arts and health in australia. Arts Health 2010, 2, 8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, S.M.; Lafrenière, D.; Brett-MacLean, P.; Collie, K.; Cooley, N.; Dunbrack, J.; Frager, G. Tipping the iceberg? The state of arts and health in canada. Arts Health 2010, 2, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staricoff, R. Arts in Health: A Review of the Medical Literature; Arts Council England: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Staricoff, R.; Clift, S. Arts and Music in Healthcare: An Overview of the Medical Literature: 2004–2011; Chelsea and Westminster Health Charity: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, C.; Pescud, M.; Anwar-McHenry, J.; Wright, P. Arts, public health and the national arts and health framework: A lexicon for health professionals. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2016, 40, 304–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klugman, C.M.; Peel, J.; Beckmann-Mendez, D. Art rounds: Teaching interprofessional students visual thinking strategies at one school. J. Assoc. Am. Med. Coll. 2011, 86, 1266–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- All-Party Parliamentary Group on Arts, Health and Wellbeing. Creative Health: The Arts for Health and Wellbeing. 2017. Available online: http://www.artshealthandwellbeing.org.uk/appg-inquiry/ (accessed on 10 August 2017).

- Sonke, J.; Pesata, V.; Nakazibwe, V.; Ssenyonjo, J.; Lloyd, R.; Espino, D.; Kerrigan, M. The arts and health communication in Uganda: A light under the table. Health Commun. 2017, 17, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambert, P.D. Managing Arts Programs in Healthcare; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fancourt, D. Arts in Health; Oxford University Press: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- National Organization for Arts in Health. Arts, Health, and Well-Being in America; National Organization for Arts in Health: San Diego, CA, USA, 2017; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Tuisku, K.; Pulkki-Råback, L.; Ahola, K.; Hakanen, J.; Virtanen, M. Cultural leisure activities and well-being at work: A study among health care professionals. J. Appl. Arts Health 2012, 2, 273–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staricoff, R.L.; Duncan, J.; Wright, M.; Loppert, S.; Scott, J. A study of the effects of the visual and performing arts in healthcare. Hosp. Dev. 2001, 32, 25–28. [Google Scholar]

- Staricoff, R.; Loppert, S. Integrating the arts into health care: Can we affect clinical outcomes. In The Healing Environment: Without and within; RCP: London, UK, 2003; pp. 63–79. [Google Scholar]

- Stuckey, H.L.; Nobel, J. The connection between art, healing, and public health: A review of current literature. Am. J. Public Health 2010, 100, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perruzza, N.; Kinsella, E.A. Creative arts occupations in therapeutic practice: A review of the literature. Br. J. Occup. Ther. 2010, 73, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, L.L. Therapeutic music research abstracts: Medical-surgical music therapy: A nursing intervention for the control of pain and anxiety in the ICU: A review of the research literature. Dimens. Crit. Care Nurs. 1995, 14, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whipple, B.; Glynn, N.J. Quantification of the effects of listening to music as a noninvasive method of pain control. Sch. Inq. Nurs. Pract. 1992, 6, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nilsson, U.; Rawal, N.; Unosson, M. A comparison of intra-operative or postoperative exposure to music-a controlled trial of the effects on postoperative pain. Anaesthesia 2003, 58, 699–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Good, M. Effects of relaxation and music on postoperative pain: A review. J. Adv. Nurs. 1996, 24, 905–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Good, M.; Stanton-Hicks, M.; Grass, J.A.; Anderson, G.C.; Lai, H.L.; Roykulcharoen, V.; Adler, P.A. Relaxation and music to reduce postsurgical pain. J. Adv. Nurs. 2001, 33, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, L.A.; MacDonald, R.A.R. An experimental investigation of the effects of preferred and relaxing music listening on pain perception. J. Music Ther. 2006, 43, 295–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonke, J. Music and the arts in health: A perspective from the United States. Music Arts Action 2011, 3, 5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, A.; Boyd, C.; Meyers, D.; Bonanno, L. Implementation of music as an anesthetic adjunct during monitored anesthesia care. J. PeriAnest. Nurs. 2010, 25, 387–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.W.; Chan, K.; Poon, C.; Ko, C.; Chan, K.; Sin, K.; Chan, A.C. Relaxation music decreases the dose of patient-controlled sedation during colonoscopy: A prospective randomized controlled trial. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2002, 55, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holm, L.; Fitzmaurice, L. Emergency department waiting room stress: Can music or aromatherapy improve anxiety scores? Pediatr. Emerg. Care 2008, 24, 836–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards, T.; Johnson, J.; Sparks, A.; Emerson, H. The effect of music therapy on patients‘ perception and manifestation of pain, anxiety, and patient satisfaction. Medsurg Nurs. 2007, 16, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dritsas, A. Music interventions as a complementary form of treatment in ICU patients. Hosp. Chron. 2013, 8, 58–59. [Google Scholar]

- Sonke, J.; Pesata, V.; Arce, L.; Carytsas, F.P.; Zemina, K.; Jokisch, C. The effects of arts-in-medicine programing on the medical-surgical work environment. Arts Health 2014, 7, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christenson, G.A. Why we need the arts in medicine. Minn. Med. 2011, 94, 49–51. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Heiney, S.P.; Darr-Hope, H. Healing icons: Art support program for patients with cancer. Cancer Pract. 1999, 7, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rollins, J.A. Tell me about it: Drawing as a communication tool for children with cancer. J. Pediatr. Oncol. Nurs. 2005, 22, 203–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. A Universal Truth: No Health without a Workforce; Global Health Workforce Alliance: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken, L.H.; Cimiotti, J.P.; Sloane, D.M.; Smith, H.L.; Flynn, L.; Neff, D.F. The effects of nurse staffing and nurse education on patient deaths in hospitals with different nurse work environments. Med. Care 2010, 49, 1047–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutney-Lee, A.; Lake, E.T.; Aiken, L.H. Development of the hospital nurse surveillance capacity profile. Res. Nurs. Health 2009, 32, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christmas, K. How work environment impacts retention. Nurs. Econ. 2008, 26, 316–318. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Repar, P.A.; Patton, D. Stress reduction for nurses through arts-in-medicine at the university of new mexico hospitals. Holist. Nurs. Pract. 2007, 21, 182–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achterberg, J. Woman as Healer; Shambala: Boston, MA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Atul Gawande on Priorities, Big and Small. 2017. Available online: https://medium.com/conversations-with-tyler/atul-gawande-checklist-books-tyler-cowen-d8268b8dfe53 (accessed on 10 August 2017).

- Flexner, A. Medical Education in the United States and Canada: A Report to the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching; Carnegie: New York, NY, USA, 1910. [Google Scholar]

- Snow, C.P. The Two Cultures; Cambridge University Press: London, UK, 1959; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Social Determinants of Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lander, D.; Graham-Pole, J. Art as a Determinant of Health; National Collaborating Centre for Determinants of Health: Antigonish, NS, Canada, 2008.

- Watson, J. The Philosophy and Science of Caring, Revised ed.; University of Colorado: Boulder, CO, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, T. Care for the Soul; Harper Collins: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, J. Art and Aesthetics in Nursing; Jones Bartlett Learning: Burlington, VT, USA, 1994; p. xvi. [Google Scholar]

- Lane, M.R. Creativity and spirituality in nursing: Implementing art in healing. Holist. Nurs. Pract. 2005, 19, 122–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rockwood-Lane, M.T.; Graham-Pole, J. The Power of Creativity in Healing: A Practice Model Demonstrating the Links between the Creative Arts and the Art of Nursing; National League for Nursing Press: New York, NY, USA, 1994; pp. 203–222. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt, M.; Wood, M. Art Therapy in Palliative Care: The Creative Response; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Imus, S. Soaring to new heights. In Proceedings of the Presentation at the American Dance Therapy Association Conference, Albuquerque, NM, USA, 11–14 October 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, H.F.; Shannon, S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacy, S.; Watson, B.R.; Riffe, D.; Lovejoy, J. Issues and best practices in content analysis. J. Mass Commun. Q. 2015, 92, 791–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, L.; Morse, J.M. Read Me First for an Introduction to Qualitative Methods; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorff, K. Reliability in content analysis. Hum. Commun. Res. 2004, 30, 411–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, T.; Jamieson, I.; Withington, J.; Hudson, D.; Dixon, A. Attracting men to nursing: Is graduate entry an answer? Nurse Educ. Pract. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Office for National Statistics. Office for National Statistics Spring 2006 Departmental Report; Office for National Statistics: London, UK, 2006.

- Marshal, E. Tranformational Leadership in Nursing; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Edelstein, L. The Hippocratic Oath, Text, Translation and Interpretation; John Hopkins Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1943. [Google Scholar]

- Bleakly, A. Working in “teams” in an era of “liquid” healthcare: What is the use of theory? J. Interprof. Care 2013, 27, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, J. Caring Science as Sacred Science; FA Davis Company: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

| Domain 1: Values and Ethics | In Data |

| Cooperation: Cooperation among those who provide care recognizing the multidisciplinary nature of health delivery systems | 31 |

| Relationships: the quality of cross-professional exchanges, and interprofessional ethical considerations in delivering health care, including mutual respect | 41 |

| Values: Consistent demonstration of core values evidenced by professionals working together, aspiring to and wisely applying principles of altruism, excellence, caring, ethics, respect, communication and accountability to achieve optimal health and wellness in individuals and communities | 10 |

| Domain 2: Roles/Responsibilities | |

| Competencies: Use unique and complementary abilities of all members of the team to optimize patient care | 31 |

| Roles: Communicate one’s roles and responsibilities clearly to patients, families, and other professionals | 0 |

| Expertise: Engage diverse healthcare professionals who complement one’s own professional expertise, as well as associated resources, to develop strategies to meet specific patient care needs | 21 |

| Roles: Explain the roles and responsibilities of other care providers and how the team works together to provide care | 7 |

| Expertise: Use the full scope of knowledge, skills, and abilities of available health professionals and healthcare workers to provide care that is safe, timely, efficient, effective, and equitable | 6 |

| Domain 3: Interprofessional communication | |

| Effective communication: Communicate consistently the importance of teamwork in patient- centered and community-focused care | 12 |

| Domain 4: Teams and Teamwork | |

| Role and competencies of the team: Integrate the knowledge and experience of other professions— appropriate to the specific care situation—to inform care decisions, while respecting patient and community values and priorities/preferences for care | 17 |

| Role and competencies of the team: Engage other health professionals—appropriate to the specific care situation—in shared patient-centered problem-solving | 14 |

| Domain 5: Quality of Care | |

| Quality enhancement: The process of taking deliberate steps at the institutional level to improve quality | 26 |

| Happy patient happy staff effect: Increasing nurse happiness by making work easier, enhancing nurse/patient communication, and increasing fulfillment with caring as a result of patients having a more positive overall experience | 8 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sonke, J.; Pesata, V.; Lee, J.B.; Graham-Pole, J. Nurse Perceptions of Artists as Collaborators in Interprofessional Care Teams. Healthcare 2017, 5, 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare5030050

Sonke J, Pesata V, Lee JB, Graham-Pole J. Nurse Perceptions of Artists as Collaborators in Interprofessional Care Teams. Healthcare. 2017; 5(3):50. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare5030050

Chicago/Turabian StyleSonke, Jill, Virginia Pesata, Jenny Baxley Lee, and John Graham-Pole. 2017. "Nurse Perceptions of Artists as Collaborators in Interprofessional Care Teams" Healthcare 5, no. 3: 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare5030050

APA StyleSonke, J., Pesata, V., Lee, J. B., & Graham-Pole, J. (2017). Nurse Perceptions of Artists as Collaborators in Interprofessional Care Teams. Healthcare, 5(3), 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare5030050