4.1. Sample Structure Analysis

A total of 26 questionnaires were distributed, targeting primary care clinic physicians in the Kinmen area, and 26 were returned, resulting in a retrieval rate of 100%. After a rigorous examination of the response content, five invalid questionnaires containing incomplete answers or logical contradictions were excluded. Finally, 21 valid questionnaires were retained, with an effective response rate of 80.8%.

Statistical analysis was conducted on the demographic variables of the valid samples (as shown in

Table 3). Regarding gender distribution, 14 physicians were male (accounting for 66.7%) and 7 were female (accounting for 33.3%). In terms of specialty distribution, Western medicine was predominant, with 13 physicians (61.9%), followed by 5 dentists (23.8%) and 3 Chinese medicine physicians (14.3%). The age range of respondents was relatively evenly distributed, mainly consisting of the 41–50 age group and the over 51 group, with 8 physicians each (38.1%), while 5 physicians were aged 31–40 (23.8%). This sample structure indicates that the interviewed physicians mostly possess rich clinical experience, making their opinions valuable for reference.

4.3. Criterion Weight Results

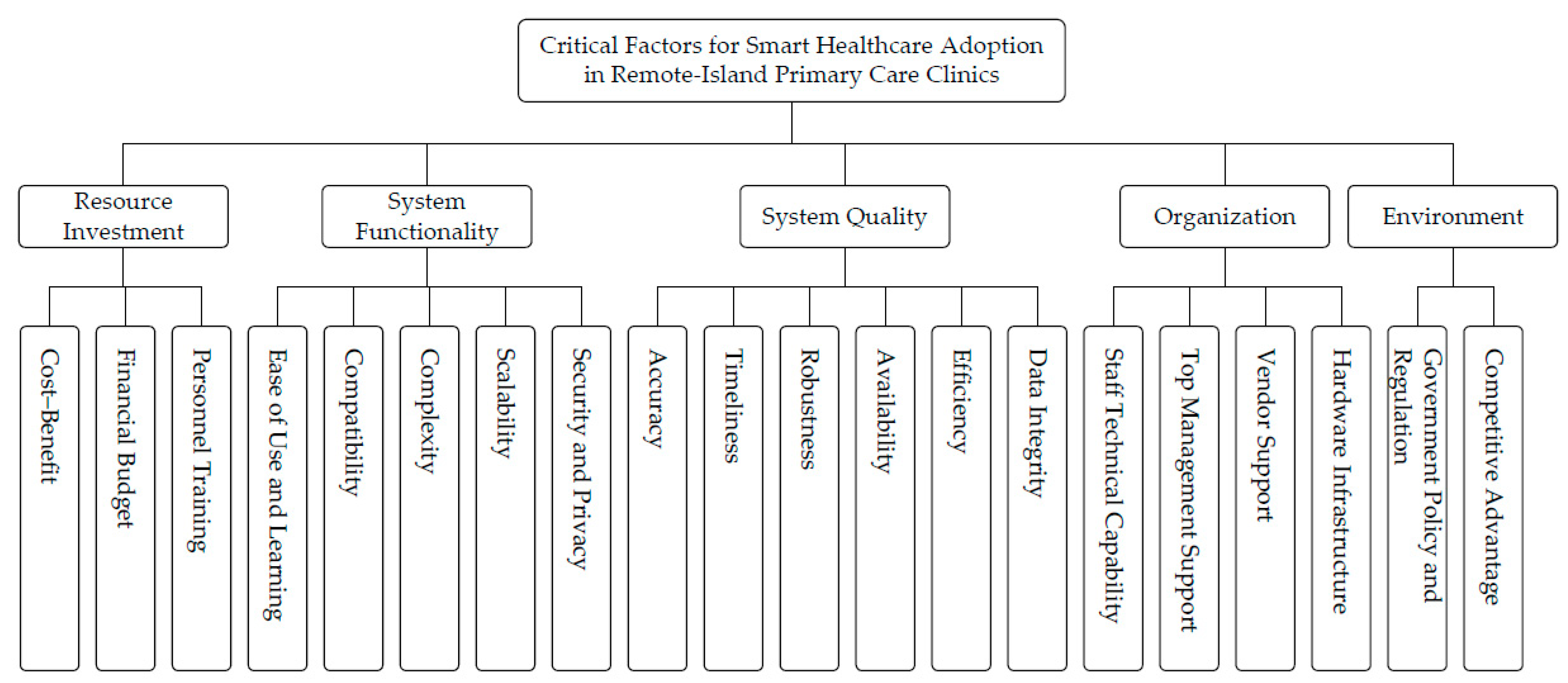

After aggregating physicians’ judgments using the AHP, the resulting weights for the main criteria and sub-criteria are reported in

Table 5. Among the main criteria, System Quality (0.308) receives the greatest weight, followed by Organization (0.221) and System Functionality (0.212), whereas Resource Investment (0.094) ranks last. This ordering suggests that, in remote-island primary care clinics, adoption priorities are primarily shaped by whether the system can provide dependable clinical information support and stable day-to-day operation, rather than by cost considerations alone.

Among the sub-criteria (global weights), Competitive Advantage (0.093) and Security and Privacy (0.091) are the two highest-ranked factors, followed by Accuracy (0.082) and Staff Technical Capability (0.074). Notably, several items share the same global weight (e.g., Compatibility and Scalability, both 0.040); such ties are reported with the same rank in

Table 5.

Overall, the pattern indicates that physicians place particular emphasis on information assurance and protection (e.g., security and privacy) and the reliability of core clinical data (e.g., accuracy and integrity), which are especially salient under geographically constrained and resource-limited service conditions.

4.5. Discussion of Research Results

This study provides empirical evidence of how physicians in remote-island primary care clinics prioritize decision criteria when considering smart healthcare adoption. Two findings are particularly noteworthy. First, technological assurance—captured by System Quality—emerges as the dominant consideration, outweighing purely financial concerns such as Resource Investment. Second, the priority structure is not uniform: subgroup analyses reveal meaningful heterogeneity across medical specialties and physician age groups, suggesting that “one-size-fits-all” adoption strategies may be ineffective in constrained primary care settings.

The dominance of System Quality can be interpreted as a rational response to high-stakes clinical work conducted in small organizations with limited operational slack. Unlike larger hospitals that may maintain IT teams, redundancy mechanisms, and formal downtime procedures, small primary care clinics often rely on lean staffing and require physicians to perform multiple roles concurrently. In such settings, instability, latency, or usability frictions can directly disrupt patient flow, increase cognitive burden, and elevate perceived clinical and legal risks. This interpretation is consistent with primary care informatics studies showing that digital tools may fail to support frontline decision-making when workflows are mismatched or when information is incomplete, untimely, or difficult to retrieve [

50,

51]. It also aligns with the “digital health divide” perspective, which emphasizes that barriers to smart healthcare adoption in underserved areas extend beyond connectivity and include trust-related concerns tied to privacy and secure handling of medical information [

52]. In this regard, the high priority assigned to Security and Privacy suggests that adoption in remote islands is not merely an efficiency initiative but also a form of risk management. Practically, vendors and policymakers should treat security assurance as an enabling condition: privacy-by-design features, audit trails, access control, and transparent data governance are likely to reduce perceived risk and strengthen clinician confidence [

52].

The prominence of Organization further indicates that smart healthcare adoption in remote-island primary care is fundamentally an organizational change process rather than a simple procurement decision. For small clinics, implementation often entails redesigning day-to-day procedures (e.g., registration, documentation, prescribing, and referrals) and depends heavily on staff competence and willingness to adapt. This is consistent with TOE-based evidence that internal readiness is a key determinant of adoption, especially in settings where resources are limited and change costs are relatively high [

35]. Related research on SMEs similarly suggests that smaller organizations face distinctive constraints—limited human resources, limited time for training, and limited capacity to absorb disruption—making organizational and managerial readiness decisive for digital initiatives [

53]. Accordingly, clinics may benefit from phased implementation, task-focused training, and clear internal role allocation for troubleshooting and vendor communication. In parallel, vendors can reduce organizational resistance by offering onboarding packages tailored to micro-organizations (e.g., clinic-ready templates, short training modules, and remote support protocols designed for limited staffing). From a policy standpoint, adoption programs should explicitly budget for training time and implementation support, as these are not peripheral costs but major determinants of sustained use.

Differences across age groups suggest that Environment operates as more than a background context in remote-island settings; it can shape the perceived feasibility and timing of adoption. Younger physicians—often in the clinic establishment or expansion phase—may be more sensitive to external resources, policy incentives, and infrastructural enabling conditions. This pattern resonates with the rural telehealth literature emphasizing the role of infrastructure and institutional support, while noting that trust and privacy concerns remain persistent barriers even when connectivity improves [

52]. Therefore, infrastructure investment and subsidy programs may be more effective when coupled with governance measures that strengthen trust (e.g., security certification, clear accountability, and data incident protocols), rather than assuming that connectivity improvements alone will ensure adoption.

A particularly original contribution of this study is the specialty-specific heterogeneity in priority profiles. Western medicine and dentistry show a stronger technology orientation and a greater intolerance for technical flaws that disrupt fast-paced workflows, whereas Chinese medicine clinics are more sensitive to resource investment and implementation burden. This can be understood as an issue of product–workflow fit: many commercial smart healthcare solutions are designed around documentation structures and clinical processes typical of Western medicine, and other specialties may face fewer mature, well-aligned options. When workflow fit is weak, clinicians may not perceive sufficient performance gains to justify switching costs, and thus, cost and organizational burden become more salient barriers [

50,

51]. These findings imply the need for differentiated strategies. Vendors should develop modular and specialty-adaptive systems (e.g., configurable documentation, specialty-specific templates, flexible pricing, and phased adoption packages). Policymakers may also consider specialty-sensitive incentives—such as targeted subsidies or shared-service platforms—to avoid within-island disparities, where only certain specialties can practically adopt and benefit from digital transformation.

From a theoretical standpoint, the results clarify boundary conditions for adoption frameworks in remote-island micro-provider contexts. TOE-based studies in healthcare often highlight organizational readiness and environmental support, while user-level models (e.g., UTAUT) emphasize performance expectancy, effort expectancy, and facilitating conditions [

54]. Our findings suggest that, in small primary care clinics under geographic and resource constraints, system quality and data assurance may function as threshold conditions that shape whether other considerations (e.g., cost, policy incentives) can meaningfully influence adoption decisions. Moreover, the observed specialty differences indicate that adoption determinants should incorporate workflow contingencies more explicitly, as the same constructs can carry different operational meanings across specialties within the same constrained geography.

Finally, this study should be interpreted with appropriate caution. Although the sample size reflects the practical constraints of recruiting physicians in remote-island settings, and some subgroup sizes are small, the identified patterns provide informative evidence and generate testable propositions for larger comparative studies across islands and urban settings.