A Systematic Review of Topic Modeling Techniques for Electronic Health Records

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (i)

- We provide an in-depth taxonomy of topic modeling techniques used in EHRs, covering probabilistic methods, matrix factorization methods, neural methods, transfer learning methods, and temporal extensions.

- (ii)

- We offer an extensive analysis of research findings, such as dataset used, evaluation measures, topic modeling technique, strengths, and limitations of these studies.

- (iii)

- We review the existing challenges to apply topic modeling in healthcare, e.g., scalability, interpretability, and data privacy, and present promising avenues for future research, including the integration of Agentic AI and large language models into clinical pathway analysis.

2. Methodology

2.1. Defining Research Questions

- RQ1: What are the predominant topic modeling approaches for EHRs and how can they be compared to each other?

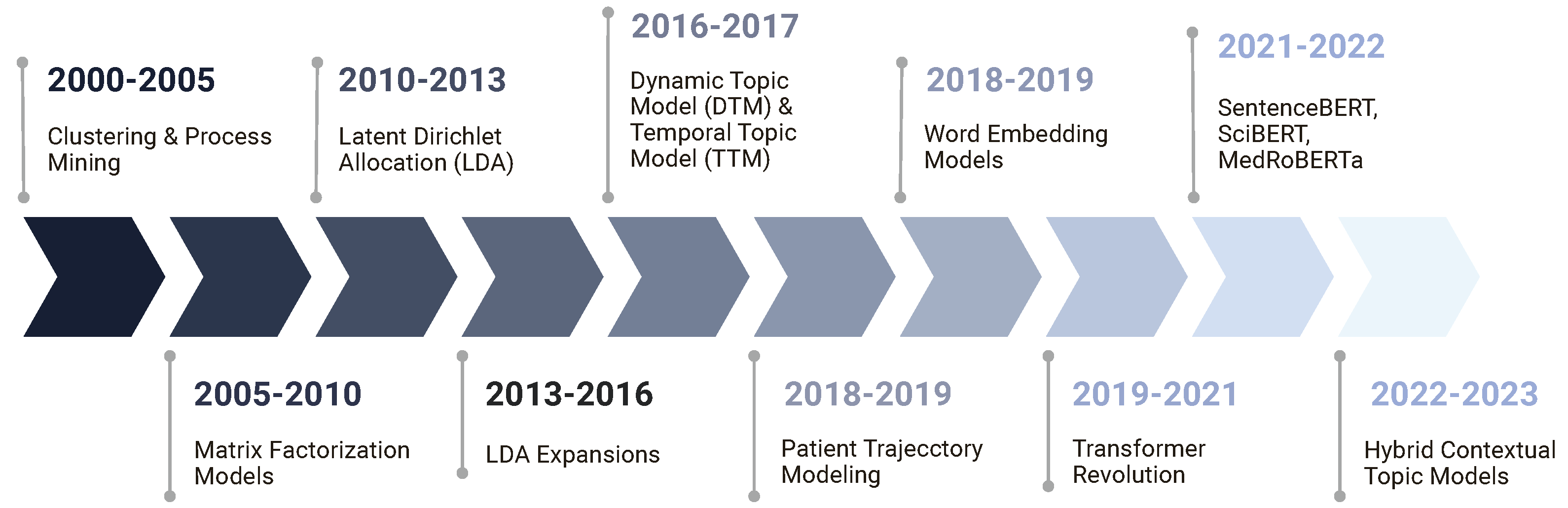

- RQ2: How have topic modeling methods evolved over time in the context of EHRs?

- RQ3: What are the strengths and weaknesses of the existing studies in EHR systems?

- RQ4: What are the challenges and future research directions in the field of topic modeling for EHRs?

2.2. Selecting Databases

2.3. Formulating Search Terms

2.4. Applying Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria and Synthesizing Articles

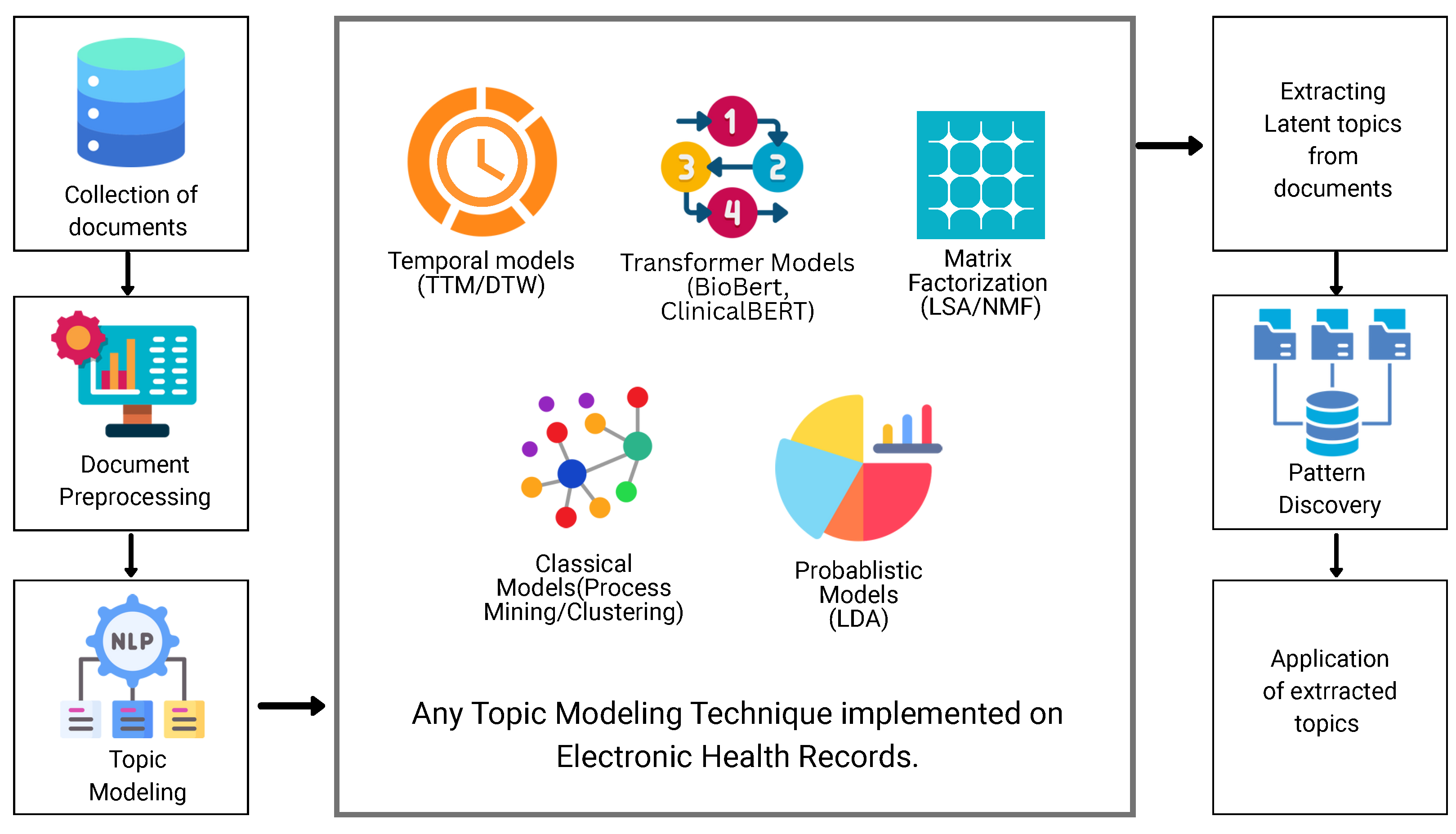

2.5. Classifying Topic Modeling Techniques for EHR

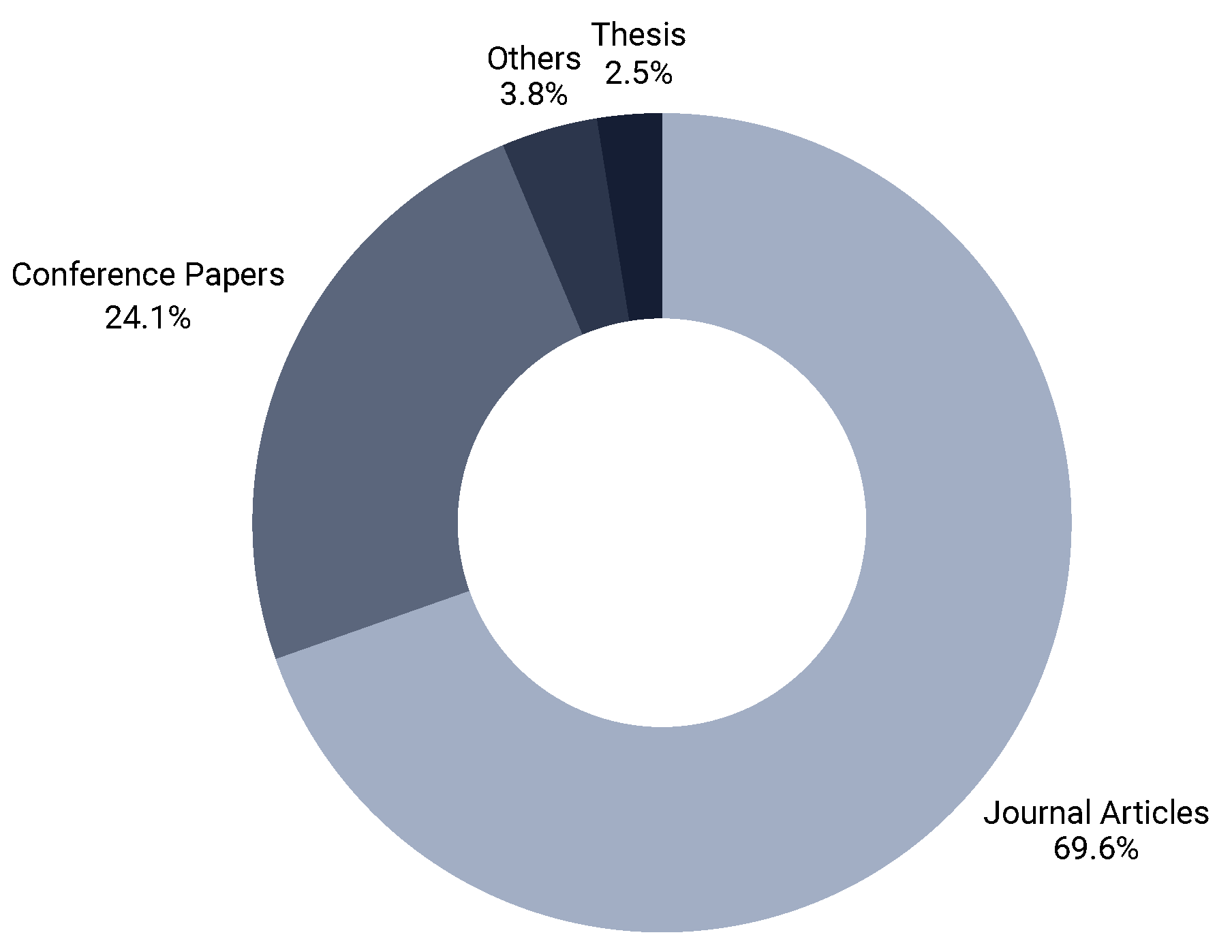

2.6. Publication and Dataset Distribution

2.7. Comparison Criteria

3. Topic Modeling Methods for Electronic Health Records

3.1. Classical Approaches

3.2. Probabilistic Topic Modeling Approaches

3.3. Matrix and Tensor Factorization Approaches

3.4. Embedding-Based and Neural Topic Models

3.5. Temporal Topic Modeling Approaches

4. Findings for the Topic Modeling Methods in EHRs

4.1. Classical Techniques

4.2. Probabilistic Topic Modeling Techniques

4.3. Matrix and Tensor Factorization Techniques

4.4. Embedding-Based and Neural Topic Modeling Techniques

4.5. Temporal Models

4.6. Hybrid Models

5. Challenges and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Singh, A. Agentic AI in Healthcare: Diagnosis and Treatment. 2025. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5214492 (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Chen, J.; Sun, L.; Guo, C.; Wei, W.; Xie, Y. A data-driven framework of typical treatment process extraction and evaluation. J. Biomed. Inform. 2018, 83, 178–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, T.; Zhao, W.; Wu, H.; Giordano, T.; Karris, M.; Napravnik, S.; Whisenant, M.; Brady, V.; Burkholder, G.; Christopoulos, K.; et al. A New Approach to Discovering HIV Symptom and Patient Clusters Using CNICS Data and Topic Modeling. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE EMBS International Conference on Biomedical and Health Informatics (BHI), Houston, TX, USA, 10–13 November 2024; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Rashid, J.; Shah, S.M.A.; Irtaza, A. A novel fuzzy k-means latent semantic analysis (FKLSA) approach for topic modeling over medical and health text corpora. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2019, 37, 6573–6588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaballa, O.; Pérez, A.; Gómez-Inhiesto, E.; Acaiturri-Ayesta, T.; Lozano, J.A. A probabilistic generative model to discover the treatments of coexisting diseases with missing data. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2024, 243, 107870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Z.; Dong, W.; Duan, H. A probabilistic topic model for clinical risk stratification from electronic health records. J. Biomed. Inform. 2015, 58, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Chen, R.; Ge, W.; Rogers, P.; Lyn-Cook, B.; Hong, H.; Tong, W.; Wu, N.; Zou, W. AI-powered topic modeling: Comparing LDA and BERTopic in analyzing opioid-related cardiovascular risks in women. Exp. Biol. Med. 2025, 250, 10389. [Google Scholar]

- Askeli, S. Diagnostic Machine Learning Utilizing Text Mining and Supervised Classification in Inborn Errors of Immunity. Master’s Thesis, Perustieteiden Korkeakoulu, Otaniemi, Finland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Lee, K.; Liu, Z.; Ma, M.; Pan, Q.; Chen, R.; Schadt, E.; Wang, X. Applying Bayesian hyperparameter optimization towards accurate and efficient topic modeling in clinical notes. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 9th International Conference on Healthcare Informatics (ICHI), Victoria, BC, Canada, 9–12 August 2021; pp. 493–494. [Google Scholar]

- Dinsa, E.F.; Das, M.; Abebe, T.U. A topic modeling approach for analyzing and categorizing electronic healthcare documents in Afaan Oromo without label information. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 32051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramoff, M.D.; Whitestone, N.; Patnaik, J.L.; Rich, E.; Ahmed, M.; Husain, L.; Hassan, M.Y.; Tanjil, M.S.H.; Weitzman, D.; Dai, T.; et al. Autonomous artificial intelligence increases real-world specialist clinic productivity in a cluster-randomized trial. npj Digit. Med. 2023, 6, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirahmadi, A.; Ohlsson, M.; Etminani, K. Deep learning prediction models based on EHR trajectories: A systematic review. J. Biomed. Inform. 2023, 144, 104430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miotto, R.; Li, L.; Kidd, B.A.; Dudley, J.T. Deep Patient: An Unsupervised Representation to Predict the Future of Patients from the Electronic Health Records. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 26094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, B.Y.; Sushil, M.; Xu, A.; Wang, M.; Arneson, D.; Berkley, E.; Subash, M.; Vashisht, R.; Rudrapatna, V.; Butte, A.J. Characterisation of digital therapeutic clinical trials: A systematic review with natural language processing. Lancet Digit. Health 2024, 6, e222–e229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Zhang, Q.; Lou, J.; Xiong, L.; Bhavani, S.; Ho, J.C. Communication Efficient Tensor Factorization for Decentralized Healthcare Networks. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Data Mining (ICDM), Auckland, New Zealand, 7–10 December 2021; pp. 1216–1221. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, K.; Li, J.; Ranganath, R. ClinicalBERT: Modeling Clinical Notes and Predicting Hospital Readmission. 2019. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:119308351 (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Li, Y.; Nair, P.; Lu, X.H.; Wen, Z.; Wang, Y.; Dehaghi, A.A.K.; Miao, Y.; Liu, W.; Ordog, T.; Biernacka, J.M.; et al. Inferring multimodal latent topics from electronic health records. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Pesaranghader, A.; Song, Z.; Verma, A.; Buckeridge, D.L.; Li, Y. Modeling electronic health record data using an end-to-end knowledge-graph-informed topic model. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 17868. [Google Scholar]

- Garriga, R.; Buda, T.S.; Guerreiro, J.; Iglesias, J.O.; Aguerri, I.E.; Matić, A. Combining clinical notes with structured electronic health records enhances the prediction of mental health crises. Cell Rep. Med. 2023, 4, 101260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkomar, A.; Oren, E.; Chen, K.; Dai, A.M.; Hajaj, N.; Hardt, M.; Liu, P.J.; Liu, X.; Marcus, J.; Sun, M.; et al. Scalable and accurate deep learning with electronic health records. npj Digit. Med. 2018, 1, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sin, C.; Yip, M. Characterizing Long COVID Patients for Enhanced Clinical Pathways: An Application of Clustering and Topic Modeling to Electronic Health Records. Master’s Thesis, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, X.; Lu, S.; Wang, L.; Li, L.; Wen, A.; Murali, S.; Liu, H. Deep Phenotyping of Obesity: Electronic Health Record–Based Temporal Modeling Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e70140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afshar, A.; Perros, I.; Park, H.; deFilippi, C.; Yan, X.; Stewart, W.; Ho, J.; Sun, J. TASTE: Temporal and static tensor factorization for phenotyping electronic health records. In Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Health, Inference, and Learning, Toronto, ON, Canada, 2–4 April 2020; pp. 193–203. [Google Scholar]

- Seymour, C.; Kennedy, J.; Wang, S.; Chang, C.-C.; Elliott, C.; Xu, Z.; Berry, S.; Clermont, G.; Cooper, G.; Gómez, H.; et al. Derivation, Validation, and Potential Treatment Implications of Novel Clinical Phenotypes for Sepsis. JAMA 2019, 321, 2003–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Guo, C.; Sun, L.; Lu, M. Mining Typical Drug Use Patterns Based on Patient Similarity from Electronic Medical Records. In Knowledge and Systems Sciences; Chen, J., Yamada, Y., Ryoke, M., Tang, X., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 71–86. [Google Scholar]

- Vathy-Fogarassy, Á.; Vassányi, I.; Kósa, I. Multi-level process mining methodology for exploring disease-specific care processes. J. Biomed. Inform. 2022, 125, 103979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniati, A.P.; Wisudiawan, G.A.A.; Kusuma, G.P.; Saadah, S.; Osman, N.A.; Zulhelmy; Wan, W.N.S.B.; Hafidz, F. Patient Clustering to Improve Process Mining for Disease Trajectory Analysis Using Indonesia Health Insurance Dataset. In Proceedings of the 2024 7th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Big Data (ICAIBD), Chengdu, China, 24–27 May 2024; pp. 88–93. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, Y.; Morris, R.S.; Bray, B.E.; Zeng-Treitler, Q. Topic Modeling Based on ICD Codes for Clinical Documents. In Intelligent Systems and Applications; Arai, K., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 184–198. [Google Scholar]

- Meaney, C.; Escobar, M.; Stukel, T.A.; Austin, P.C.; Jaakkimainen, L. Comparison of Methods for Estimating Temporal Topic Models from Primary Care Clinical Text Data: Retrospective Closed Cohort Study. JMIR Med. Inform. 2022, 10, e40102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, J.; Pérez, A.; Casillas, A.; Gojenola, K. Cardiology record multi-label classification using latent Dirichlet allocation. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2018, 164, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Lakin, J.; Riley, C.; Korach, T.; Frain, L.; Zhou, L. Disease Trajectories and End-of-Life Care for Dementias: Latent Topic Modeling and Trend Analysis Using Clinical Notes. AMIA Annu. Symp. Proc. 2018, 2018, 1056. [Google Scholar]

- Bagheri, A.; Sammani, A.; van der Heijden, P.G.M.; Asselbergs, F.W.; Oberski, D.L. ETM: Enrichment by topic modeling for automated clinical sentence classification to detect patients’ disease history. J. Intell. Inf. Syst. 2020, 55, 329–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puerari, I.; Duarte, D.; Bianco, G.D.; Lima, J.F. Exploratory Analysis of Electronic Health Records using Topic Modeling. J. Inf. Data Manag. 2021, 11, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, M.; Jurkovitz, C.; Shatkay, H. Identifying patterns of associated-conditions through topic models of Electronic Medical Records. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM), Shenzhen, China, 15–18 December 2016; pp. 466–469. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Grant, A.V.; Li, Y. Implementation of a graph-embedded topic model for analysis of population-level electronic health records. STAR Protoc. 2023, 4, 101966. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kang, H.; Yu, Z.; Gong, Y. Initializing and Growing a Database of Health Information Technology (HIT) Events by Using TF-IDF and Biterm Topic Modeling. AMIA Annu. Symp. Proc. 2018, 2017, 1024–1033. [Google Scholar]

- D’Souza, E.W.; MacGregor, A.J.; Markwald, R.R.; Elkins, T.A.; Zouris, J.M. Investigating insomnia in United States deployed military forces: A topic modeling approach. Sleep Health 2024, 10, 75–82. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, P.; Xu, T.; Wang, Y. Learning Personalized Treatment Rules from Electronic Health Records Using Topic Modeling Feature Extraction. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Data Science and Advanced Analytics (DSAA), Washington, DC, USA, 5–8 October 2019; pp. 392–402. [Google Scholar]

- Martinis, M.C.; Amodeo, A.; Facente, V.; Greco, F.; Zucco, C. Leveraging Topic Modeling in the Analysis of Urology Medical Reports. In Proceedings of the 2024 Fourth International Conference on Digital Data Processing (DDP), New York, NY, USA, 25–27 September 2024; pp. 118–122. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Z.; Nair, P.; Deng, C.-Y.; Lu, X.H.; Moseley, E.; George, N.; Lindvall, C.; Li, Y. Mining heterogeneous clinical notes by multi-modal latent topic model. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0249622. [Google Scholar]

- Kondratieff, K.E.; Brown, J.T.; Barron, M.; Warner, J.L.; Yin, Z. Mining Medication Use Patterns from Clinical Notes for Breast Cancer Patients Through a Two-Stage Topic Modeling Approach. AMIA Summits Transl. Sci. Proc. 2022, 2022, 303–312. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, A.; Banerjee, T.; Romine, W.L.; Thirunarayan, K.; Chen, L.; Cajita, M. Mining Themes in Clinical Notes to Identify Phenotypes and to Predict Length of Stay in Patients admitted with Heart Failure. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Digital Health (ICDH), Chicago, IL, USA, 2–8 July 2023; pp. 208–216. [Google Scholar]

- Ahuja, Y.; Zou, Y.; Verma, A.; Buckeridge, D.; Li, Y. MixEHR-Guided: A guided multi-modal topic modeling approach for large-scale automatic phenotyping using the electronic health record. J. Biomed. Inform. 2022, 134, 104190. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.; Wang, Z.; Song, Z.; Buckeridge, D.; Li, Y. MixEHR-Nest: Identifying Subphenotypes within Electronic Health Records through Hierarchical Guided-Topic Modeling. In Proceedings of the 15th ACM International Conference on Bioinformatics, Computational Biology and Health Informatics, Shenzhen, China, 22–25 November 2024. Article No. 53. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Yang, A.Y.; Marelli, A.; Li, Y. MixEHR-SurG: A joint proportional hazard and guided topic model for inferring mortality-associated topics from electronic health records. J. Biomed. Inform. 2024, 153, 104638. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.H.; Goldstein, M.K.; Asch, S.M.; Mackey, L.; Altman, R.B. Predicting inpatient clinical order patterns with probabilistic topic models vs conventional order sets. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2017, 24, 472–480. [Google Scholar]

- Lebeña, N.; Blanco, A.; Pérez, A.; Casillas, A. Preliminary exploration of topic modelling representations for Electronic Health Records coding according to the International Classification of Diseases in Spanish. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 204, 117303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Sumba, X.T.; Xu, Y.; Liu, A.; Guo, L.; Powell, G.; Verma, A.; Buckeridge, D.; Marelli, A.; Li, Y. Supervised multi-specialist topic model with applications on large-scale electronic health record data. In Proceedings of the 12th ACM International Conference on Bioinformatics, Computational Biology, and Health Informatics, Gainesville, FL, USA, 1–4 August 2021. Article No. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Ramon-Gonen, R.; Dori, A.; Shelly, S. Towards a practical use of text mining approaches in electrodiagnostic data. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 19483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rijcken, E.; Scheepers, F.; Zervanou, K.; Spruit, M.; Mosteiro, P.; Kaymak, U. Towards Interpreting Topic Models with ChatGPT. In Proceedings of the IFSA 2023 Conference, Denver, CO, USA, 25–29 September 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Therneau, T.M.; Atkinson, E.J.; Tafti, A.P.; Zhang, N.; Amin, S.; Limper, A.H.; Khosla, S.; Liu, H. Unsupervised machine learning for the discovery of latent disease clusters and patient subgroups using electronic health records. J. Biomed. Inform. 2020, 102, 103364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, A.D.; Greene, J.D.; Liu, V.X.; Ray, P. Unsupervised probabilistic models for sequential Electronic Health Records. J. Biomed. Inform. 2022, 134, 104163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noble, P.J.M.; Appleton, C.; Radford, A.D.; Nenadic, G. Using topic modelling for unsupervised annotation of electronic health records to identify an outbreak of disease in UK dogs. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0260402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Schlueter, D.J.; Wu, P.; Kerchberger, V.E.; Rosenbloom, S.T.; Wells, Q.S.; Feng, Q.P.; Denny, J.C.; Wei, W.Q. Detecting time-evolving phenotypic topics via tensor factorization on electronic health records: Cardiovascular disease case study. J. Biomed. Inform. 2019, 98, 103270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; El-Kareh, R.; Sun, J.; Yu, H.; Jiang, X. Discriminative and Distinct Phenotyping by Constrained Tensor Factorization. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karami, A.; Gangopadhyay, A.; Zhou, B.; Kharrazi, H. Fuzzy Approach Topic Discovery in Health and Medical Corpora. Int. J. Fuzzy Syst. 2018, 20, 1334–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassaine, A.; Canoy, D.; Solares, J.R.A.; Zhu, Y.; Rao, S.; Li, Y.; Zottoli, M.; Rahimi, K.; Salimi-Khorshidi, G. Learning multimorbidity patterns from electronic health records using Non-negative Matrix Factorisation. J. Biomed. Inform. 2020, 112, 103606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malakouti, S.; Hauskrecht, M. Predicting Patient’s Diagnoses and Diagnostic Categories from Clinical-Events in EHR Data. In Artificial Intelligence in Medicine; Riaño, D., Wilk, S., ten Teije, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 125–130. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Feng, Q.; Wu, P.; Warner, J.L.; Denny, J.C.; Wei, W.-Q. Using topic modeling via non-negative matrix factorization to identify relationships between genetic variants and disease phenotypes: A case study of Lipoprotein (a) (LPA). PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0212112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roosan, D.; Khan, R.; Essien-Aleksi, I.; Nirzhor, S.; Hai, F. Empowering Clinicians with an Agentic AI for Voice-Driven EHR Exploration. 2025. Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/pacis2025 (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Li, J.; Namvar, M.; Akhlaghpour, S.; Indulska, M. Constructing Patient Representation through Semi-Supervised Topic Modeling. 2024. Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/pacis2024/track11_healthit/track11_healthit/13 (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Li, Y.; Rao, S.; Solares, J.R.A.; Hassaine, A.; Ramakrishnan, R.; Canoy, D.; Zhu, Y.; Rahimi, K.; Salimi-Khorshidi, G. BEHRT: Transformer for Electronic Health Records. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 7155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Speier, W.; Ong, M.K.; Arnold, C.W. Bidirectional Representation Learning From Transformers Using Multimodal Electronic Health Record Data to Predict Depression. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2021, 25, 3121–3129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, J.; Hu, Y.; Li, L.; Erzurumluoglu, A.M.; Braenne, I.; Whitehurst, C.; Schmitz, J.; Arora, J.; Bartholdy, B.A.; Gandhi, S.; et al. Deep representation learning for clustering longitudinal survival data from electronic health records. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saigaonkar, S.; Narawade, V. Domain adaptation of transformer-based neural network model for clinical note classification in Indian healthcare. Int. J. Inf. Technol. 2024, 16, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Cutrona, S.L.; Dharod, A.; Moses, A.; Bridges, A.; Ostasiewski, B.; Foley, K.L.; Houston, T.K. iDAPT Implementation Science Center for Cancer Control. Electronic health record activity changes around new decision support implementation: Monitoring using audit logs and topic modeling. JAMIA Open 2025, 8, ooaf050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, M.; Peter, O.; Pattipaka, T. ExBEHRT: Extended Transformer for Electronic Health Records. In Trustworthy Machine Learning for Healthcare; Chen, H., Luo, L., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 73–84. [Google Scholar]

- Kraljevic, Z.; Bean, D.; Shek, A.; Bendayan, R.; Hemingway, H.; Yeung, J.A.; Deng, A.; Baston, A.; Ross, J.; Idowu, E.; et al. Foresight—A generative pretrained transformer for modelling of patient timelines using electronic health records: A retrospective modelling study. Lancet Digit. Health 2024, 6, e281–e290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Speier, W.; Ong, M.; Arnold, C.W. HCET: Hierarchical clinical embedding with topic modeling on electronic health records for predicting future depression. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2021, 25, 1124–1133. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, T.; Rizvi, S.A.; Thakur, R.K.; Socrates, V.; Gupta, M.; van Dijk, D.; Taylor, R.A.; Ying, R. HEART: Learning better representation of EHR data with a heterogeneous relation-aware transformer. J. Biomed. Inform. 2024, 159, 104741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Mamouei, M.; Salimi-Khorshidi, G.; Rao, S.; Hassaine, A.; Canoy, D.; Lukasiewicz, T.; Rahimi, K. Hi-BEHRT: Hierarchical Transformer-Based Model for Accurate Prediction of Clinical Events Using Multimodal Longitudinal Electronic Health Records. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2023, 27, 1106–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Hou, J.; Bonzel, C.L.; Zhao, Y.; Castro, V.M.; Weisenfeld, D.; Cai, T.; Ho, Y.L.; Panickan, V.A.; Costa, L.; et al. LATTE: Label-efficient incident phenotyping from longitudinal electronic health records. Patterns 2024, 5, 100906. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmy, L.; Xiang, Y.; Xie, Z.; Tao, C.; Zhi, D. Med-BERT: Pretrained contextualized embeddings on large-scale structured electronic health records for disease prediction. npj Digit. Med. 2021, 4, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.M.; Hauskrecht, M. Modeling multivariate clinical event time-series with recurrent temporal mechanisms. Artif. Intell. Med. 2021, 112, 102021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, Y.; Speier, W.; Ong, M.; Arnold, C.W. Multi-Level Embedding with Topic Modeling on Electronic Health Records for Predicting Depression. In Explainable AI in Healthcare and Medicine: Building a Culture of Transparency and Accountability; Shaban-Nejad, A., Michalowski, M., Buckeridge, D.L., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 241–246. [Google Scholar]

- Nogues, I.E.; Wen, J.; Zhao, Y.; Bonzel, C.L.; Castro, V.M.; Lin, Y.; Xu, S.; Hou, J.; Cai, T. Semi-supervised Double Deep Learning Temporal Risk Prediction (SeDDLeR) with Electronic Health Records. J. Biomed. Inform. 2024, 157, 104685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Mitra, A.; Liu, W.; Berlowitz, D.; Yu, H. TransformEHR: Transformer-based encoder-decoder generative model to enhance prediction of disease outcomes using electronic health records. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7857. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Silva, R.P.; Pollettini, J.T.; Pazin Filho, A. Unsupervised natural language processing in the identification of patients with suspected COVID-19 infection. Cad. Saude Publica 2023, 39, e00243722. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neil, S.T.; Madlock-Brown, C.; Wilkins, K.J.; McGrath, B.M.; Davis, H.E.; Assaf, G.S.; Wei, H.; Zareie, P.; French, E.T.; Loomba, J.; et al. Finding Long-COVID: Temporal topic modeling of electronic health records from the N3C and RECOVER programs. npj Digit. Med. 2024, 7, 296. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, B.C.; Achenbach, P.; Dunne, J.L.; Hagopian, W.; Lundgren, M.; Ng, K.; Veijola, R.; Frohnert, B.I.; Anand, V. Modeling Disease Progression Trajectories from Longitudinal Observational Data. Annu. Symp. Proc. 2021, 2020, 668. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H. Patient Subtyping via Learning Hidden Markov Models from Pairwise Co-occurrences in EHR Data. In Proceedings of the 2024 46th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), Orlando, FL, USA, 15–19 July 2024; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.; Ge, Z.; Dong, W.; He, K.; Duan, H. Probabilistic modeling personalized treatment pathways using electronic health records. J. Biomed. Inform. 2018, 86, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Min, X.; Ye, P.; Xie, W.; Zhao, D. Temporal topic model for clinical pathway mining from electronic medical records. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2024, 24, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Dormosh, N.; Abu-Hanna, A.; Calixto, I.; Schut, M.C.; Heymans, M.W.; van der Velde, N. Topic evolution before fall incidents in new fallers through natural language processing of general practitioners’ clinical notes. Age Ageing 2024, 53, afae016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Huang, W.; Zhao, W.; Zhou, X.; Shi, N.; Xia, Q. Exploring Acute Pancreatitis Clinical Pathways Using a Novel Process Mining Method. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tianzhao, L.; Jinzhi, H.; Rong, Z.; Jun, S.; Hailong, L.; Yan, L. Revolutionizing clinical decision making through deep learning and topic modeling for pathway optimization. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 28787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, Z.; Li, M.; Ni, X.; Tan, R.; Zhang, W.; Wubulaishan, M.; Wang, W.; Yuan, Z.; Zhang, Z.; et al. A feasibility study of automating radiotherapy planning with large language model agents. Phys. Med. Biol. 2025, 70, 075007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genovese, A.; Borna, S.; Gomez-Cabello, C.A.; Haider, S.A.; Prabha, S.; Forte, A.J.; Veenstra, B.R. Artificial intelligence in clinical settings: A systematic review of its role in language translation and interpretation. Ann. Transl. Med. 2024, 12, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenk, J.; Voigt, I.; Inojosa, H.; Schlieter, H.; Ziemssen, T. Building digital patient pathways for the management and treatment of multiple sclerosis. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1356436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Inclusion Criteria |

|---|

| Articles on topic modeling, topic modeling using Electronic Health Records, topic modeling in clinical pathway analysis, topic modeling in healthcare, latent topic discovery in healthcare |

| Articles that use EHR data |

| Articles published in conferences, journals, and workshops |

| Articles published from 2015 to 2025 |

| Articles in English language |

| Exclusion Criteria |

| Articles not about topic modeling in healthcare |

| Theoretical papers without empirical methodology or metrics |

| Gray literature (not published in any reputable venue or not peer-reviewed) |

| Papers published before 2015 |

| Publications not in English |

| Category | Keywords/Terms |

|---|---|

| Target Domain (A) | “Electronic Health Records”, “EHR”, “Clinical Notes”, “Structured Records” |

| Core Method (B) | “Topic Model*”, “Latent Dirichlet Allocation”, “LDA”, “NMF”, “Neural Topic Model” |

| Technical Focus (C) | “Temporal”, “Longitudinal”, “Sequential”, “Transformers”, “LLM”, “Agentic” |

| Application (D) | “Clinical Pathway”, “Phenotyping”, “Risk Stratification”, “Comorbidity” |

| Full Boolean String | (A) AND (B) AND (C OR D) |

| Filters Applied | Date: 2015–2025; Language: English; Document Type: Article, Conference Paper |

| Dataset | Availability | Modality | Clinical Domain | Country | Dominant Techniques | Methodological Interaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIMIC | Public | Notes + structured | Critical care/ICU | USA | Probabilistic, Temporal, Neural-based Approaches | Ideal for NLP-heavy models extracting semantics from dense notes. |

| UK Biobank | Restricted | Structured + genomic | Population-scale studies | UK | Matrix Factorization, Embedding | Sparse categorical matrices favor dimensionality reduction. |

| Proprietary EHRs | Restricted/ Proprietary | Multi-modal (Notes, codes, labs) | Multiple domains | Multiple | Temporal, Embedding/Neural-based Approaches | Fragmented, longitudinal events necessitate temporal and neural layers. |

| Metric/Symbol | ★ | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Highly sensitive | Moderately sensitive | Low sensitivity |

| Computation Cost | High cost | Moderate cost | Low cost |

| Complexity | High complexity | Moderate complexity | Low complexity |

| Scalability | Low scalability | Moderate scalability | High scalability |

| Symbol | Meaning | ||

| ✓ | Included/Addressed: | Present in the proposed framework/model | |

| ✗ | Not Included/Absent: | Not addressed or missing in the model | |

| Ref. No. | Year | Technique | Data Modality | Sequence Discovery | Rule-Based/ Heuristic | Reliance on Clinical Ontology | Qualitative Evaluation | Generalizability | Discrete Patient Clusters Discovery | Coding/Log Quality Dependency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [24] | 2019 | Consensus Clustering | Structured Only | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| [28] | 2022 | ICD TM (Code Co-occurrence) | Structured Only | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ |

| [26] | 2022 | MEDCP (Process Mining) | Structured Only | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ |

| [27] | 2024 | Patient Similarity + Process Mining | Structured Only | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ |

| [2] | 2018 | Patient Similarity + Pattern Mining | Structured Only | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ |

| [25] | 2018 | Sequence/Pattern Mining | Structured Only | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ |

| [8] | 2024 | TF-IDF + Supervised Classifier | Mixed (Text+Struct) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Ref. No. | Year | Technique | Modeling Type | Data Modality | Data Limitation | Qualitative Evaluation | Quantitative Evaluation | Short/Noisy Text | Auxiliary Learning | Computation Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [21] | 2020 | LDA (Gensim) | Phenotype | Text Only | Note Quality | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| [49] | 2023 | LDA+text mining | Phenotype | Multi-Modal | Single Site | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| [42] | 2023 | LDA+clustering | Phenotype | Multi-Modal | Preprocessing Sensitivity | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| [48] | 2021 | MixEHR-S (Supervised BTM) | Prediction | Multi-Modal | Curated Inputs | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ★ |

| [31] | 2018 | LDA | Thematic Analysis | Text Only | Note Quality | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| [44] | 2024 | MixEHR-Nest (Hier. Guided TM) | Phenotype | Multi-Modal | Ontology Mapping Quality | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ★ |

| [35] | 2023 | G-ETM (Graph Embedded TM) | Phenotype | Multi-Modal | Graph Quality | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ★ |

| [51] | 2020 | LDA+PDM clustering | Phenotype | Structured Only | Coding Bias | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| [40] | 2021 | MNTM (Multi-Note TM) | Thematic Analysis | Text Only | Note Type Labels | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| [38] | 2019 | LDA(feature for ITR) | Risk Strat. | Multi-Modal | Assumption Sensitive | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | |

| [30] | 2018 | LDA + supervised classification | Prediction | Text Only | Preprocessing Sensitivity | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | |

| [53] | 2021 | LDA (annotation for surveillance) | Surveillance | Text Only | Short-Text Sensitivity | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | |

| [39] | 2024 | LDA (urology clinical text) | Thematic Analysis | Text Only | Small Dataset | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| [45] | 2024 | MixEHR-SurG (guided BTM+Cox) | Risk Strat. | Multi-Modal | PheCode Priors Quality | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ★ |

| [9] | 2021 | LDA + Bayesian optimization | Thematic Analysis | Text Only | Metric-Dependent Performance | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| [17] | 2020 | MixEHR (multi-modal BTM) | Phenotype | Multi-Modal | Discretization/Scaling | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ★ |

| [47] | 2022 | LDA + feature-engineered ICD | Prediction | Text Only | Polysemy/Short Text | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| [36] | 2018 | BTM + TF-IDF classifiers | Prediction | Text Only | Noisy Texts | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| [52] | 2022 | Sequence latent variable model | Phenotype | Structured Only | Complex Inference | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ★ |

| [41] | 2022 | CTM→STM (two-stage TM) | Thematic Analysis | Text Only | Note Completeness | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| [6] | 2015 | PRSM (LDA-based for risk strat.) | Risk Strat. | Structured Only | Coded EHR Quality | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | |

| [37] | 2024 | LDA-style (clinical notes) | Thematic Analysis | Text Only | Note Quality/Variability | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| [10] | 2024 | LDA (low-resource language) | Thematic Analysis | Text Only | Low-Resource Language | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| [34] | 2016 | LDA-style (co-occurrence) | Thematic Analysis | Multi-Modal | Coding/Preprocessing | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| [46] | 2017 | Clinical LDA variant | Prediction | Structured Only | Institution-Specific Bias | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | |

| [32] | 2020 | ETM (LDA+ supervised classifier) | Prediction | Text Only | LDA Weak for Short Text | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| [43] | 2022 | MixEHR-Guided (semi-supervised) | Phenotype | Multi-Modal | Needs Strong Surrogates | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ★ |

| [50] | 2023 | LDA+ChatGPT (TM+LLM) | Thematic Analysis | Text Only | LLM Hallucination | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| [3] | 2024 | LDA/BERTopic + clustering | Phenotype | Multi-Modal | Text/Site Variation | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| [33] | 2021 | LDA-like + supervised LOS pred. | Prediction | Text Only | Limited Generalizability | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ |

| Ref. No. | Year | Technique | Factorization Type | Data Modality | Temporal Dynamics | Subphenotype Utility | Handles Fuzziness | Computation Cost | Sensitivity to Data Sparsity | Model Extensibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [54] | 2019 | Constrained NTF (CP/PARAFAC) | Tensor | Structured Only | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ★ | ★ | ✓ |

| [59] | 2019 | NMF (Phenome-Genome) | Matrix | Structured Only | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| [58] | 2019 | LSI (SVD-based) | Matrix | Structured Only | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ★ | ✗ | |

| [29] | 2020 | NMF (Temporal Topic Modeling) | Matrix | Text Only | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| [55] | 2017 | Constrained NTF | Tensor | Structured Only | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ★ | ✓ | |

| [57] | 2020 | NMF (Temporal Multimorbididty Phenotyping) | Matrix | Structured Only | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ★ | ✗ | |

| [23] | 2020 | PARAFAC2 + NMF (Joint TF) | Tensor | Structured Only | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ★ | ✓ | |

| [56] | 2018 | FLSA (Fuzzy LSA) | Matrix | Text Only | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Ref. No. | Year | Technique | Core Architecture Type | Data Modality | Learning Strategy | Temporal Modeling | High Prediction Accuracy | Model Extensibility | Interpretability Mechanism | Computation Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [64] | 2025 | VaDeSCEHR | RNN/DNN/ VAE | Structured Codes Only | End-to-End Sup. | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | Topic-Informed | ★ |

| [20] | 2018 | Deep DNN on FHIR | RNN/DNN/ VAE | Multi-Modal | End-to-End Sup. | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ★ |

| [73] | 2021 | BERT-style embeddings | Transformer | Structured Codes Only | Self-Sup. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ★ |

| [22] | 2025 | Temporal deep rep + clustering | RNN/DNN/ VAE | Multi-Modal | Semi-Sup. | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | Topic-Informed | ★ |

| [67] | 2023 | Transformer (BEHRT extension) | Transformer | Multi-Modal | End-to-End Sup. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Feature Importance | ★ |

| [65] | 2024 | SMDBERT++ | Transformer | Text Only | Semi-Sup. | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ★ |

| [72] | 2024 | LATTE | Hybrid Deep | Structured Codes Only | Semi-Sup. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Feature Importance | ★ |

| [76] | 2024 | SeDDLeR | RNN/DNN/ VAE | Structured Codes Only | Semi-Sup. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ★ |

| [63] | 2021 | Bidirectional Transformer | Transformer | Multi-Modal | Self-Sup. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ★ |

| [75] | 2021 | Hybrid: Hierarchical + Topic | Hybrid Deep | Multi-Modal | End-to-End Sup. | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | Topic-Informed | ★ |

| [13] | 2016 | Stacked Denoising AE | RNN/DNN/ VAE | Structured Codes Only | Self-Sup. | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ★ |

| [69] | 2021 | HCET (Topic-informed Hier.) | Hybrid Deep | Multi-Modal | End-to-End Sup. | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | Topic-Informed | ★ |

| [62] | 2021 | BERT-style Transformer | Transformer | Structured Codes Only | Self-Sup. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ★ |

| [71] | 2023 | Hierarchical Transformer | Transformer | Multi-Modal | Self-Sup. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ★ |

| [68] | 2024 | GPT-style Transformer | Transformer | Multi-Modal | Self-Sup. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ★ |

| [16] | 2019 | ClinicalBERT | Transformer | Text Only | Self-Sup. | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ★ |

| [70] | 2024 | HEART (Rel. Aware Trans.) | Transformer | Structured Codes Only | Self-Sup. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ★ |

| [66] | 2025 | LLM-assisted pathway extraction | Transformer | Multi-Modal | Semi-Sup. | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | Topic-Informed | ★ |

| [74] | 2021 | Recurrent temporal model | RNN/DNN/ VAE | Structured Codes Only | End-to-End Sup. | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| [77] | 2023 | Transformer encoder-decoder | Transformer | Structured Codes Only | Self-Sup. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ★ |

| [78] | 2023 | BERTopic | Transformer | Text Only | Unsup. | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | Expert Validation | |

| [7] | 2025 | LDA vs BERTopic | Transformer | Text Only | Unsup. | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | Topic-Informed | ★ |

| [61] | 2024 | Seed-guided semi-supervised TM | RNN/DNN/ VAE | Text Only | Semi-Sup. | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | Topic-Informed | ★ |

| Ref. No. | Year | Technique | Core Temporal Mechanism | Data Modality | Modeling Focus | Interpretation Focus | Model Complexity | Scalability | Sensitivity to Binning/ Preprocessing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [5] | 2024 | Probabilistic Latent State Model | HMM/Latent State | Structured Sequences | Comorbidity | Comorbidity Linkage | ★ | ||

| [83] | 2024 | Hidden Markov Model (HMM) | HMM/Latent State | Structured Sequences | Phenotype | State Transition | ★ | ||

| [79] | 2024 | Temporal Topic Model (Unsupervised LDA) | Time-Aware LDA | Structured Sequences | Phenotype | Topic Trajectory | ★ | ||

| [80] | 2021 | Temporal Topic Model (LDA + time) | Time-Aware LDA | Structured Sequences | Treatment Flow | Topic Trajectory | ★ | ||

| [81] | 2024 | Hidden Markov Model (HMM) | HMM/Latent State | Structured Sequences | Progression | State Transition | |||

| [84] | 2024 | Dynamic Topic Modeling (DTM) | Dynamic Topic Model | Text | Evolution | Topic Trajectory | ★ | ★ | |

| [82] | 2018 | Latent Treatment Topic Model (HMM-like) | HMM/Latent State | Structured Sequences | Treatment Flow | State Transition |

| Ref. No. | Year | Technique | Hybridization Type | Interpretability Mechanism | Data Modality | Incorporates Deep Learning | Handles Temporal Data | Computation Cost | Sensitivity to Fusion | Predictive Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [4] | 2019 | FKLSA (Fuzzy K-Means + LSA + PCA) | Feature Fusion | Topic Coherence | Text | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| [86] | 2025 | LDA + BiLSTM | Feature Fusion | Topic Coherence | Mixed | ✓ | ✓ | ★ | ★ | ✓ |

| [18] | 2022 | KG-TM (Probabilistic Topic + KG Embeddings) | Knowledge-Guided | Concept Linking | Structured | ✗ | ✗ | ★ | ✓ | |

| [85] | 2023 | Fuzzy Process Mining + Transformer | Feature Fusion | Feature Importance | Structured | ✓ | ✓ | ★ | ✓ |

| Technique | Impact of Scalability | Impact of Interpretability | Impact of Temporal Complexity | Impact of Privacy Concerns |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical Techniques | Scalable for mid-sized EHRs; efficiency drops with expanding clinical vocabularies. | Frequency-based transparency of reason; lacks multi-faceted topic depth. | Static architecture; unable to model sequential clinical visits or disease progression. | Requires centralized raw data; complicates patient de-identification. |

| Probabilistic Topic Modeling | Slow inference on large-scale EHRs; limits real-time decision support. | High clinical utility via word-probability distributions matching medical terminology. | Standard bag-of-words approach; ignores clinical event ordering. | Raw co-occurrence reliance; hinders decentralized/private implementation. |

| Matrix and Tensor Factorization | Mathematically scalable but high storage demand for sparse matrices. | Readable mathematical components; lacks probabilistic uncertainty modeling. | Supports time dimensions; complexity grows exponentially with visit frequency. | Operates on aggregated, de-identified matrices; avoids raw text exposure. |

| Embedding and Neural Topic Modeling | Highly robust; handles millions of records via mini-batch SGD. | Abstract latent spaces; difficult for clinicians to audit topic assignments. | Static by default; requires sequential layers (LSTM/Transformers) which increase training time. | Federated learning compatible; shares model weights without exposing raw EHR data. |

| Temporal Models | Increased complexity per time-step; long-term longitudinal analysis is significantly slower. | High utility for tracking disease evolution and patient journey trajectories. | Natively designed for temporal EHR richness; addresses a key SLR gap. | Identifiable sequential patterns; harder to anonymize than static records. |

| Hybrid Models | Dependent on complex components; combination overhead slows large-scale EHR processing. | Enhanced utility; leverages multiple methods to compensate for individual interpretability weaknesses. | Often acts as a temporal patch for static models; prone to sensitivity issues during feature fusion. | Variable; contingent on reliance upon raw text features versus processed embeddings. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mehmood, I.; Zahra, Z.; Iqbal, S.; Qahmash, A.; Hussain, I. A Systematic Review of Topic Modeling Techniques for Electronic Health Records. Healthcare 2026, 14, 282. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14020282

Mehmood I, Zahra Z, Iqbal S, Qahmash A, Hussain I. A Systematic Review of Topic Modeling Techniques for Electronic Health Records. Healthcare. 2026; 14(2):282. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14020282

Chicago/Turabian StyleMehmood, Iqra, Zoya Zahra, Sarah Iqbal, Ayman Qahmash, and Ijaz Hussain. 2026. "A Systematic Review of Topic Modeling Techniques for Electronic Health Records" Healthcare 14, no. 2: 282. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14020282

APA StyleMehmood, I., Zahra, Z., Iqbal, S., Qahmash, A., & Hussain, I. (2026). A Systematic Review of Topic Modeling Techniques for Electronic Health Records. Healthcare, 14(2), 282. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14020282