Psychometric Evidence of Instruments for Assessing Mental Health in Older Adults from Latin America and the Caribbean: A Scoping Review

Highlights

- Most studies assessing mental health in older adults from Latin America and the Caribbean focused primarily on cognitive function, with a predominance of research conducted in Brazil.

- There are a lack of standardized validity criteria, and few studies address psychosocial or emotional dimensions of mental health in aging.

- There is an urgent need to develop and validate culturally sensitive instruments that assess the broader spectrum of mental health in older adults.

- Expanding validated instruments across countries in the region would improve the quality and comparability of research and clinical practice.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

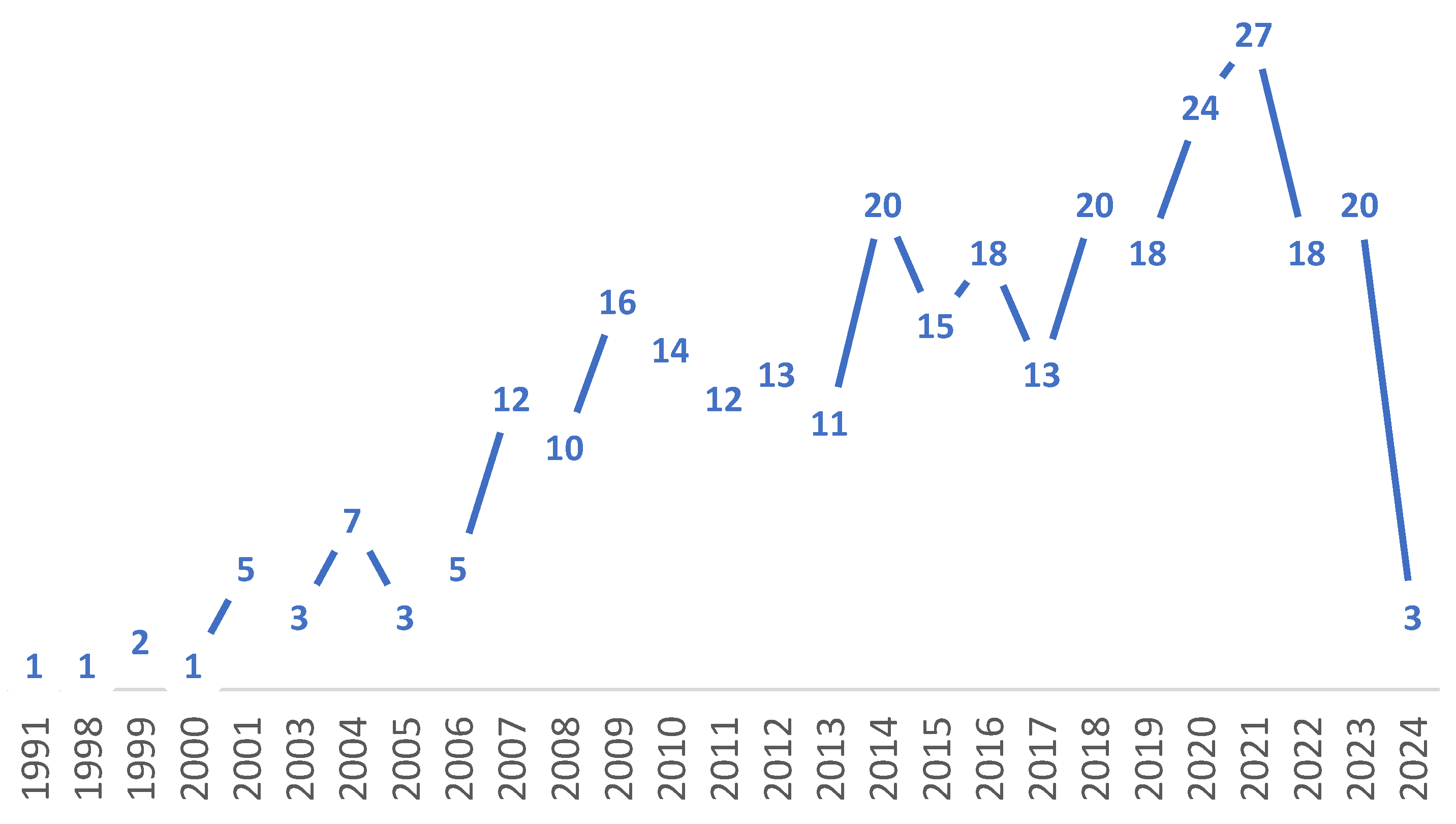

3.1. Synthesis by Country and Temporal Distribution of Studies

3.2. Synthesis by Instrument and Outcome Measured

3.3. Synthesis by Type of Analysis Performed to Validate Instruments

3.4. Practical Guide for Clinicians and Researchers: Using the Charting Data in Supplementary Materials Document S3

- Country-based selection: Clinicians should first identify instruments validated in their country or in culturally similar settings, as psychometric properties are context-dependent and not universally transferable.

- Outcome-oriented filtering: The “Purpose” column allows users to identify instruments according to the clinical or research outcome of interest (e.g., cognitive functioning, depressive symptoms, quality of life).

- Assessment of psychometric robustness: The “Analyses performed” column enables evaluation of the strength of validity evidence. Instruments supported by multiple sources of evidence (e.g., reliability, validity, diagnostic accuracy) should be prioritized over those based on a single analysis.

- Population and setting alignment: Information on sample characteristics and recruitment settings (e.g., urban or rural) allows clinicians to assess the similarity between the validation sample and their own patient population, which is particularly relevant in the heterogeneous LAC context.

4. Discussion

- Evidence based on internal structure: Although factor analysis was reported in 35.3% of studies to provide evidence of internal structure, the low frequency of divergent validity (9.6%) suggests that little attention was paid to establishing the distinctiveness of the measured constructs.

- Evidence based on relations to other variables: A substantial proportion of studies (47.8%) focused on diagnostic accuracy, offering evidence based on relations to other variables, such as criterion validity, sensitivity, and specificity.

- Reliability evidence: Although reliability was the most frequently reported analysis (64.4%), it primarily reflects internal consistency and stability. While these are necessary, they are insufficient on their own to support a comprehensive validity argument.

- Expand the scope of validation to include affective, psychosocial, and positive mental health constructs (e.g., depression, loneliness, resilience, coping, and well-being), taking a multi-dimensional approach to mental health in older adults.

- Apply advanced psychometric approaches, such as item response theory and Rasch models, to improve the precision, invariance, and fairness of measurements across diverse contexts.

- Include underrepresented populations (e.g., rural, indigenous, and socioeconomically marginalized older adults) to ensure that the instruments are valid, equitable, and contextually appropriate.

- Prioritize cultural adaptation over simple translation to ensure that instruments are sensitive to the linguistic, cultural, and socio-economic heterogeneity of the ageing population.

- Move away from single-metric reports towards comprehensive validity arguments that incorporate multiple sources of evidence, including content and fairness evidence.

- Strengthen collaborative regional networks to develop cross-cultural research, moving away from isolated national studies towards shared regional standards.

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Mental Health of Older Adults; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025; Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-of-older-adults (accessed on 29 December 2025).

- World Health Organization. The WHO Special Initiative for Mental Health (2019–2023): Universal Health Coverage for Mental Health. 2019. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/310981 (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Thumala, D.; Gajardo, B.; Gómez, C.; Arnold-Cathalifaud, M.; Araya, A.; Jofré, P.; Ravera, V. Coping processes that foster accommodation to loss in old age. Aging Ment. Health 2020, 24, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, C.F.; Jeste, D.V.; Sachdev, P.S.; Blazer, D.G. Mental health care for older adults: Recent advances and new directions in clinical practice and research. World Psychiatry 2022, 21, 336–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamaria-Garcia, H.; Sainz-Ballesteros, A.; Hernandez, H.; Moguilner, S.; Maito, M.; Ochoa-Rosales, C.; Corley, M.; Valcour, V.; Miranda, J.J.; Lawlor, B.; et al. Factors associated with healthy aging in Latin American populations. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 2248–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan American Health Organization. Mental Health. Available online: https://www.paho.org/en/topics/mental-health (accessed on 29 December 2025).

- Ali, G.C.; Ryan, G.; De Silva, M.J. Validated Screening Tools for Common Mental Disorders in Low and Middle Income Countries: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0156939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karel, M.J.; Gatz, M.; Smyer, M.A. Aging and mental health in the decade ahead: What psychologists need to know. Am. Psychol. 2012, 67, 184–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychological Association. Guidelines for Psychological Practice with Older Adults. 2024. Available online: https://www.apa.org/practice/guidelines/guidelines-psychological-practice-older-adults.pdf (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- American Educational Research Association; American Psychological Association. National Council on Measurement in Education. In Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing; American Educational Research Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Iliescu, D.; Greiff, S.; Rusu, A. Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses in Psychological Assessment. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2024, 40, 341–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonda, S.J.; Herzog, A.R. Patterns and Risk Factors of Change in Somatic and Mood Symptoms among Older Adults. Ann. Epidemiol. 2001, 11, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegeman, J.M.; de Waal, M.W.M.; Comijs, H.C.; Kok, R.M.; van der Mast, R.C. Depression in later life: A more somatic presentation? J. Affect. Disord. 2015, 170, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela, M.; Miranda-Castillo, C.; Paddick, S.-M.; León-Campos, M.O.; Molleda, P.; Rosell, J. Scoping Review Protocol: Psychometric Evidence of Instruments for Assessing Mental Health in Older Adults from Latin America and the Caribbean. OSF. 2026; Registered on 15 January. Available online: https://osf.io/yft2k/overview (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folstein, M.F.; Folstein, S.E.; McHugh, P.R. “Mini-mental state”: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1975, 12, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasreddine, Z.S.; Phillips, N.A.; Bédirian, V.; Charbonneau, S.; Whitehead, V.; Collin, I.; Cummings, J.L.; Chertkow, H. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: A Brief Screening Tool for Mild Cognitive Impairment. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2005, 53, 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathuranath, P.S.; Nestor, P.J.; Berrios, G.E.; Rakowicz, W.; Hodges, J.R. A brief cognitive test battery to differentiate Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia. Neurology 2000, 55, 1613–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulman, K.I.; Shedletsky, R.; Silver, I.L. The challenge of time: Clock-drawing and cognitive function in the elderly. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 1986, 1, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorm, A.F.; Jacomb, P.A. The Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE): Socio-demographic correlates, reliability, validity, and some norms. Psychol. Med. 1989, 19, 1015–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storey, J.E.; Rowland, T.J.; Conforti, D.A.; Dickson, H.G. The Rowland Universal Dementia Assessment Scale (RUDAS): A multicultural cognitive assessment scale. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2004, 16, 13–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yesavage, J.A.; Brink, T.L.; Rose, T.L.; Lum, O.; Huang, V.; Adey, M.; Leirer, V.O. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: A preliminary report. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1982, 17, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radloff, L.S. The CES-D Scale. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1977, 1, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The WHOQOL Group. The World Health Organization quality of life assessment (WHOQOL): Development and general psychometric properties. Soc. Sci. Med. 1998, 46, 1569–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ware, J.E.; Sherbourne, C.D. The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36). Med. Care 1992, 30, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, C.; García, C.; Adana, L.; Yacelga, T.; Rodríguez Lorenzana, A.; Maruta, C. Use of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) in Latin America: A systematic review. Rev. Neurol. 2018, 66, 397–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, F.S.; Teixeira-Santos, A.C.; Leist, A.K. The prevalence of mild cognitive impairment in Latin America and the Caribbean: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging Ment. Health 2022, 26, 1710–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aravena, J.M.; Gajardo, J.; Saguez, R.; Hinton, L.; Gitlin, L.N. Nonpharmacologic Interventions for Family Caregivers of People Living with Dementia in Latin America: A Scoping Review. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2022, 30, 859–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solano-Flores, G. How Serious are We About Fairness in Testing and How Far are We Willing to Go? A Response to Randall and Bennett with Reflections About the Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing. Educ. Assess. 2023, 28, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzheimer’s Disease International. World Alzheimer Report 2023: Reducing Dementia Risk: Never Too Early, Never Too Late. 2023. Available online: https://www.alzint.org/u/World-Alzheimer-Report-2023.pdf (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Pan American Health Organization. Dementia in Latin America and the Caribbean: Prevalence, Incidence, Impact, and Trends over Time; Pan American Health Organization: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, L.; Tang, E.; Taylor, J.P. Dementia: Timely diagnosis and early intervention. BMJ 2015, 350, h3029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, T.; Zhao, X.; Wu, M.; Li, Z.; Luo, L.; Yang, C.; Yang, F. Prevalence of depression in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2022, 311, 114511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Jin, Y.; Liu, R.; Zhang, Q.; Su, Z.; Ungvari, G.S.; Tang, Y.L.; Ng, C.H.; Li, X.H.; Xiang, Y.T. Global prevalence of depression in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological surveys. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2023, 80, 103417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jalali, A.; Ziapour, A.; Karimi, Z.; Rezaei, M.; Emami, B.; Kalhori, R.P.; Khosravi, F.; Sameni, J.S.; Kazeminia, M. Global prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress in the elderly population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2024, 24, 809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salari, N.; Najafi, H.; Rasoulpoor, S.; Canbary, Z.; Heidarian, P.; Mohammadi, M. The global prevalence and associated factors of loneliness in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan American Health Organization. COVID-19 Pandemic Triggers 25% Increase in Prevalence of Anxiety and Depression Worldwide; Pan American Health Organization: Washington, DC, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.paho.org/en/news/2-3-2022-covid-19-pandemic-triggers-25-increase-prevalence-anxiety-and-depression-worldwide (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Kathiresan, P.; Rathod, S.; Balhara, Y.P.S.; Phiri, P.; Bhargava, R. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Mental Health of Middle-Aged and Older Adults. Prim. Care Companion CNS Disord. 2025, 27, 25m03963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Pérez, A.; González-Aragón Pineda, A.E.; Sandoval-Bonilla, B.A.; Cruz-Hervert, L.P. Prevalence and factors associated with the depressive symptoms in rural and urban Mexican older adults: Evidence from the Mexican Health and Aging Study 2018. Salud Publica Mex. 2022, 64, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevisan, F.K.; Silva, R.H.D.; Reis, S.F.A.; Giehl, M.W.C. Prevalence of depressive symptoms and associated factors in Brazilian older adults: 2019 Brazilian National Health Survey. Cad. Saude Publica 2024, 40, e00006124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres Mantilla, J.C.; Torres Mantilla, J.D. Factores asociados al trastorno depresivo en adultos mayores peruanos. Horiz. Med. 2023, 23, e2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, X.; Gajardo, J.; Monsalves, M.J. Gender differences in positive screen for depression and diagnosis among older adults in Chile. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan American Health Organization/World Health Organization. PAHO and AFSM Promote Discussion on Resilience for Healthy Aging; Pan American Health Organization (PAHO): Washington, DC, USA, 2025; Available online: https://www.paho.org/en/news/27-3-2025-paho-and-afsm-promote-discussion-resilience-healthy-aging (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Pham, M.N.; Bhar, S. Stressors and Life Satisfaction in Older Adults: The Moderating Role of Self-Efficacy. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2025, 102, 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trică, A.; Golu, F.; Sava, N.I.; Licu, M.; Zanfirescu, Ș.A.; Adam, R.; David, I. Resilience and successful aging: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Psychol. 2024, 248, 104357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aged Care Research & Industry Innovation Australia|ARIIA. Screening Tools Mental Health & Wellbeing. Evidence Them. ARIIA Knowledge & Implementation Hub. Published online. 2023. Available online: https://www.ariia.org.au/sites/default/files/2022-10/mental-health-%26-wellbeing--screening-tools.pdf (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Aryadoust, V.; Tan, H.A.H.; Ng, L.Y. A scientometric review of Rasch measurement: The rise and progress of a specialty. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Committee on Psychological Testing B on the H of SPI of M (IOM). Psychological Testing in the Service of Disability Determination; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, D.J. Psychometric Validity. In The Wiley Handbook of Psychometric Testing; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 751–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukamel, D.B.; Chou, C.C.; Zimmer, J.G.; Rothenberg, B.M. The Effect of Accurate Patient Screening on the Cost-Effectiveness of Case Management Programs. Gerontologist 1997, 37, 777–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pachana, N.A.; Helmes, E.; Byrne, G.J.A.; Edelstein, B.A.; Konnert, C.A.; Pot, A.M. Screening for mental disorders in residential aged care facilities. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2010, 22, 1107–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iragorri, N.; Spackman, E. Assessing the value of screening tools: Reviewing the challenges and opportunities of cost-effectiveness analysis. Public Health Rev. 2018, 39, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Older adults (aged 60+ or mean age ≥ 60). | Samples not stratified by age or younger populations. |

| Concept | Psychometric instruments assessing mental health disorders or psychosocial outcomes relevant to mental health in older adults (e.g., cognition, depression, anxiety, resilience, quality of life). | Studies not addressing mental health assessment, focusing solely on physical health outcomes, or describing instruments without a clear link to mental health. |

| Context | Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) region. | Studies conducted outside the LAC region, or with mixed samples where LAC-specific data were not reported. |

| Study Design | Studies reporting at least one psychometric property, including adaptation, translation, development, reliability, validity, diagnostic accuracy, factor structure, or normative data. | Instrument development studies without any psychometric evaluation or validation-related analyses. |

| Sources | Peer-reviewed articles published between 1990 and 2024 in English, Spanish, or Portuguese. | Duplicates, conference abstracts, editorials, reviews, or studies published in languages other than those specified. |

| Stage (PRISMA-ScR) | Actions and Rigor Safeguards |

|---|---|

| 1. Research question identification | The research question was defined using the PCC (Population, Concept, Context) framework, with a focus on the psychometric evidence of mental health assessment instruments for older adults in LAC. |

| 2. Identification of relevant studies | A comprehensive search was conducted in the following formal databases: PubMed, CINAHL, Medline, Embase, SciELO, Scopus, Web of Science, and PsycINFO. Searches were performed in Spanish, Portuguese, and English using a trilingual glossary. The whole search strategy and limits are reported in Supplementary Materials Document S1. |

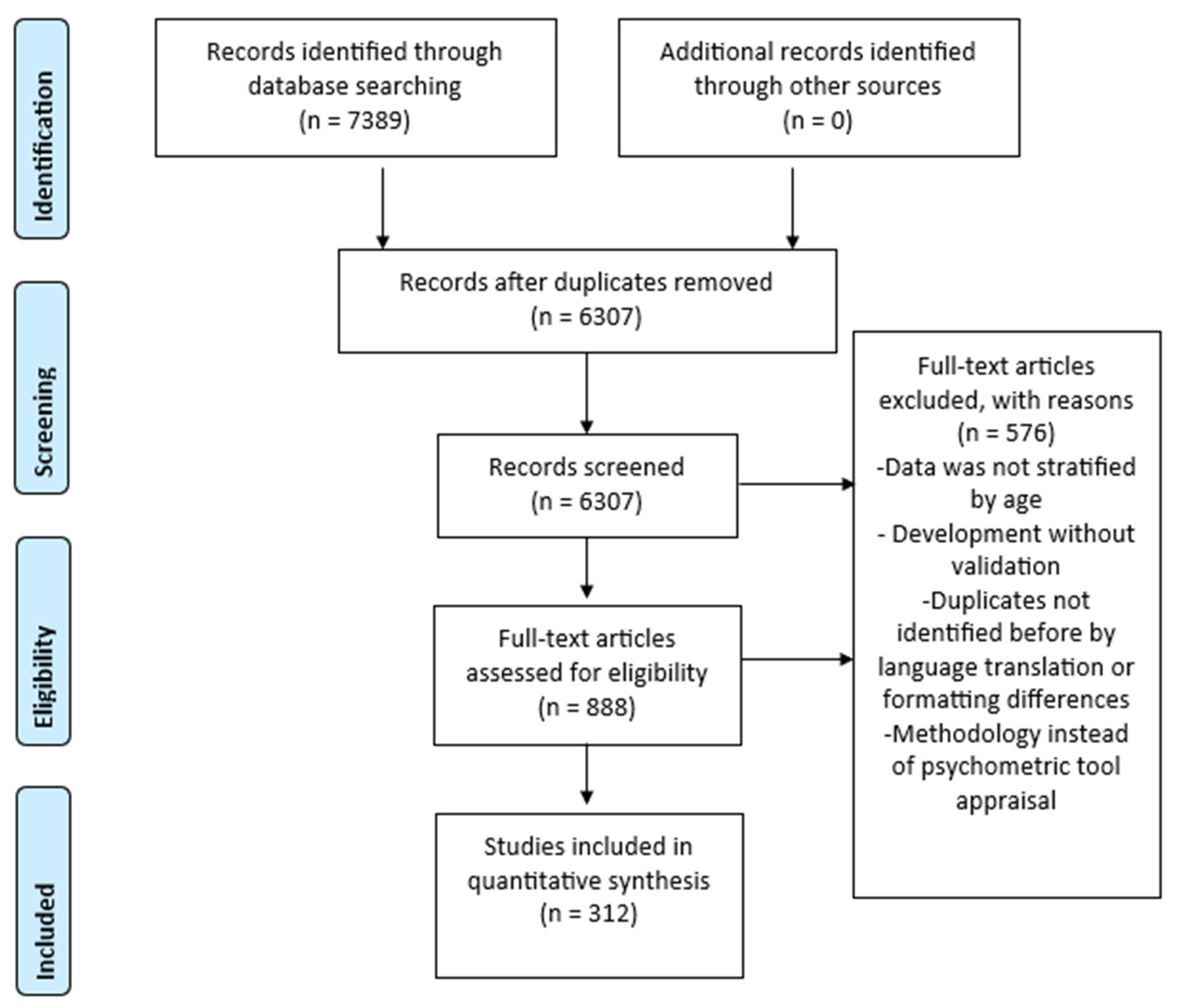

| 3. Study screening and selection | The title and abstract were screened independently by four reviewers using the Rayyan QCRI tool in a blind process. Any discrepancies were resolved by a fifth senior reviewer acting as arbitrator [16]. The selection process is summarised in a PRISMA-ScR flow diagram (Figure 1). |

| 4. Data charting and extraction | A standardised data extraction form was developed by two reviewers and refined by two more. The form was piloted on selected studies to ensure consistency and relevance before complete data extraction. |

| 5. Collating, summarizing, and reporting results | The data were organised into a charting extraction (see Supplementary Materials Document S3), which included study characteristics, sample details, instrument features, and psychometric analyses. The results were synthesized descriptively and analytically, and organised by country, instrument, purpose, and type of psychometric evidence. |

| Country | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Brazil | 153 | 49.04 |

| Chile | 36 | 11.54 |

| Peru | 31 | 9.94 |

| Mexico | 30 | 9.62 |

| Colombia | 20 | 6.41 |

| Argentina | 19 | 6.09 |

| LA | 12 | 3.85 |

| Cuba | 3 | 0.96 |

| Costa Rica | 2 | 0.64 |

| Ecuador | 2 | 0.64 |

| Venezuela | 2 | 0.64 |

| Peru and Spain | 1 | 0.32 |

| Spain, Cuba, and Colombia | 1 | 0.32 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Miranda-Castillo, C.; Paddick, S.-M.; León-Campos, M.O.; Molleda, P.; Rosell, J.; Valenzuela, M. Psychometric Evidence of Instruments for Assessing Mental Health in Older Adults from Latin America and the Caribbean: A Scoping Review. Healthcare 2026, 14, 265. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14020265

Miranda-Castillo C, Paddick S-M, León-Campos MO, Molleda P, Rosell J, Valenzuela M. Psychometric Evidence of Instruments for Assessing Mental Health in Older Adults from Latin America and the Caribbean: A Scoping Review. Healthcare. 2026; 14(2):265. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14020265

Chicago/Turabian StyleMiranda-Castillo, Claudia, Stella-Maria Paddick, María O. León-Campos, Pedro Molleda, Javiera Rosell, and Margarita Valenzuela. 2026. "Psychometric Evidence of Instruments for Assessing Mental Health in Older Adults from Latin America and the Caribbean: A Scoping Review" Healthcare 14, no. 2: 265. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14020265

APA StyleMiranda-Castillo, C., Paddick, S.-M., León-Campos, M. O., Molleda, P., Rosell, J., & Valenzuela, M. (2026). Psychometric Evidence of Instruments for Assessing Mental Health in Older Adults from Latin America and the Caribbean: A Scoping Review. Healthcare, 14(2), 265. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14020265