Strengthening the Culture of Well-Being in Rural Hospitals Through RISE Peer Support

Highlights

- Implementation of the RISE peer support program in two rural hospital systems led to modest reductions in anxiety and burnout and early, significant increases in workforce resilience.

- Staff reported major improvements in awareness, accessibility, and perceived usefulness of peer support, reflecting a strengthened culture of well-being within rural healthcare settings.

- Peer support programs such as RISE are feasible, acceptable, and impactful even in resource-limited rural hospitals, offering a scalable model for workforce well-being.

- Rural health systems can enhance clinician retention, psychological safety, and organizational support culture by adopting structured emotional-support interventions tailored to local context.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.2. Survey Sites

2.3. Intervention

2.4. Measures

2.5. Randomization

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants Characteristics

3.2. RISE Implementation

3.3. Anxiety, Burnout and Resilience Outcomes

3.4. Culture of Wellbeing

3.5. Awareness of RISE

3.6. Contextual Differences

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maslach, C.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Leiter, M.P. Job burnout. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Committee on Systems Approaches to Improve Patient Care by Supporting Clinician Well-Being. Taking Action Against Clinician Burnout: A Systems Approach to Professional Well-Being; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mohr, D.C.; Elnahal, S.; Marks, M.L.; Derickson, R.; Osatuke, K. Burnout Trends Among US Health Care Workers. JAMA Netw. Open 2025, 8, e255954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parandeh, A.; Ashtari, S.; Rahimi-Bashar, F.; Gohari-Moghadam, K.; Vahedian-Azimi, A. Prevalence of burnout among healthcare workers during coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2022, 53, 564–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, C.P.; Dyrbye, L.N.; Sinsky, C.; Trockel, M.; Tutty, M.; Nedelec, L.; Carlasare, L.E.; Shanafelt, T.D. Resilience and burnout among physicians and the general US working population. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e209385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Izquierdo, M.; Meseguer de Pedro, M.; Ríos-Risquez, M.I.; Sánchez, M.I.S. Resilience as a Moderator of Psychological Health in Situations of Chronic Stress (Burnout) in a Sample of Hospital Nurses. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2018, 50, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salari, N.; Khazaie, H.; Hosseinian-Far, A.; Khaledi-Paveh, B.; Kazeminia, M.; Mohammadi, M.; Shohaimi, S.; Daneshkhah, A.; Eskandari, S. The prevalence of stress, anxiety and depression within front-line healthcare workers caring for COVID-19 patients: A systematic review and meta-regression. Hum. Resour. Health 2020, 18, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.; Ma, S.; Wang, Y.; Cai, Z.; Hu, J.; Wei, N.; Wu, J.; Du, H.; Chen, T.; Li, R.; et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among healthcare workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e203976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strasser, R.; Kam, S.M.; Regalado, S.M. Rural healthcare access and policy in developing countries. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2016, 37, 395–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, D. The role of rural graduate medical education in improving rural health and healthcare. Fam. Med. 2021, 53, 540–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDowell, M.; Glasser, M.; Fitts, M.; Nielsen, K.; Hunsaker, M. A national view of rural health workforce issues in the USA. Rural Remote Health 2010, 10, 1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bethea, A.; Samanta, D.; Kali, M.; Lucente, F.C.; Richmond, B.K. The impact of burnout syndrome on practitioners working within rural healthcare systems. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2020, 38, 582–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, C.L.; Abreu, L.C.; Ramos, J.L.S.; Castro, C.F.D.; Smiderle, F.R.N.; Santos, J.A.D.; Bezerra, I.M.P. Influence of burnout on patient safety: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicina 2019, 55, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipos, D.; Goyal, R.; Zapata, T. Addressing burnout in the healthcare workforce: Current realities and mitigation strategies. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2024, 42, 100961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willard-Grace, R.; Knox, M.; Huang, B.; Hammer, H.; Kivlahan, C.; Grumbach, K. Burnout and healthcare workforce turnover. Ann. Fam. Med. 2019, 17, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakerman, J.; Humphreys, J.; Russell, D.; Guthridge, S.; Bourke, L.; Dunbar, T.; Zhao, Y.; Ramjan, M.; Murakami-Gold, L.; Jones, M.P. Remote health workforce turnover and retention: What are the policy and practice priorities? Hum. Resour. Health 2019, 17, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, M.; Penalosa, M.; Busch, I.M.; Burhanullah, H.; Weston, C.; Weeks, K.; Connors, C.; Michtalik, H.J.; Everly, G.; Wu, A.W. Rural healthcare workers’ well-being: A systematic review of support interventions. Fam. Syst. Health 2024, 42, 355–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasbrouck, M.A.; Waddimba, A.C. The work-related stressors and coping strategies of group-employed rural healthcare practitioners: A qualitative study. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2017, 60, 867–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasky, T.; Samanta, D.; Sebastian, W.; Calderwood, L. Resilience in rural health system. Clin. Teach. 2024, 21, e13726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, C.P.; Dyrbye, L.N.; Erwin, P.J.; Shanafelt, T.D. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2016, 388, 2272–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edrees, H.; Connors, C.; Paine, L.; Norvell, M.; Taylor, H.; Wu, A.W. Implementing the RISE second victim support programme at the Johns Hopkins Hospital: A case study. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e011708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connors, C.A.; Norvell, M.; Wu, A.W. The RISE (Resilience in Stressful Events) peer support program: Creating a virtuous cycle of healthcare leadership support for staff resilience and well-being. J. Healthc. Leadersh. 2024, 16, 537–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connors, C.A.; Dukhanin, V.; March, A.L.; Parks, J.A.; Norvell, M.; Wu, A.W. Peer support for nurses as second victims: Resilience, burnout, and job satisfaction. J. Patient Saf. Risk Manag. 2019, 25, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, D.; Wu, A.W.; Connors, C.; Chappidi, M.R.; Sreedhara, S.K.; Selter, J.H.; Padula, W.V. Cost-benefit analysis of a support program for nursing staff. J. Patient Saf. 2020, 16, e250–e254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.; Löwe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaishnavi, S.; Connor, K.; Davidson, J.R. An abbreviated version of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC), the CD-RISC2: Psychometric properties and applications in psychopharmacological trials. Psychiatry Res. 2007, 152, 293–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li-Sauerwine, S.; Rebillot, K.; Melamed, M.; Addo, N.; Lin, M. A 2-Question Summative Score Correlates with the Maslach Burnout Inventory. West. J. Emerg. Med. 2020, 21, 610–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chari, R.; Sauter, S.L.; Petrun Sayers, E.L.; Huang, W.; Fisher, G.G.; Chang, C.C. Development of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health Worker Well-Being Questionnaire. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2022, 64, 707–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adair, K.C.; Heath, A.; Frye, M.A.; Frankel, A.; Proulx, J.; Rehder, K.J.; Eckert, E.; Penny, C.; Belz, F.; Sexton, J.B. The Psychological Safety Scale of the Safety, Communication, Operational, Reliability, and Engagement (SCORE) Survey: A Brief, Diagnostic, and Actionable Metric for the Ability to Speak Up in Healthcare Settings. J. Patient Saf. 2022, 18, 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Huber, P.J. The behavior of maximum likelihood estimates under nonstandard conditions. In Proceedings of the Fifth Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1967; Volume 1, pp. 221–233. [Google Scholar]

- White, H.L., Jr. A heteroskedasticity-consistent covariance matrix estimator and a direct test for heteroskedasticity. Econometrica 1980, 48, 817–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- StataCorp LLC. Stata Statistical Software: Release 18, version 18.0.27; StataCorp LLC: College Station, TX, USA, 2023.

- Tolins, M.L.; Rana, J.S.; Lippert, S.; LeMaster, C.; Kimura, Y.F.; Sax, D.R. Implementation and effectiveness of a physician-focused peer support program. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0292917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Swarbrick, M.; Ayyala, M.S.; Chen, P.H.; Brazeau, C.M.L.R. Cultivating Connections: An Interprofessional Peer Support Model. Psychiatr. Serv. 2024, 76, 289–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carbone, R.; Ferrari, S.; Callegarin, S.; Casotti, F.; Turina, L.; Artioli, G.; Bonacaro, A. Peer support between healthcare workers in hospital and out-of-hospital settings: A scoping review. Acta Biomed. 2022, 93, e2022308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmins, G.; Williamson, S.; Cassells, A.; Davis, K.; Dong, L.; Tobin, J.N.; Gidengil, C.; Meredith, L.S.; Chen, P.G. Health care worker experiences with a brief peer support and well-being intervention during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2025, 25, 1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fallon, P.; Jaegers, L.A.; Zhang, Y.; Dugan, A.G.; Cherniack, M.; El Ghaziri, M. Peer Support Programs to Reduce Organizational Stress and Trauma for Public Safety Workers: A Scoping Review. Workplace Health Saf. 2023, 71, 523–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, B.; Ahmadzadeh, A.; Haris, K.; Jiang, S.; Chesney, T.R.; MacRae, H.; Louridas, M. Peer Support Programs for Physicians and Health Care Providers: A Scoping Review. Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Patient Saf. 2025, 51, 589–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, C.P.; Dyrbye, L.N.; Satele, D.V.; Shanafelt, T.D. Colleagues Meeting to Promote and Sustain Satisfaction (COMPASS) Groups for Physician Well-Being: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2021, 96, 2606–2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sexton, J.B.; Adair, K.C.; Profit, J.; Milne, J.; McCulloh, M.; Scott, S.; Frankel, A. Perceptions of institutional support for “second victims” associated with safety culture and workforce well-being. Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Patient Saf. 2021, 47, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Nachreiner, F.; Schaufeli, W.B. The job demands-resources model of burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, I.M.; Moretti, F.; Campagna, I.; Benoni, R.; Tardivo, S.; Wu, A.W.; Rimondini, M. Promoting the psychological well-being of healthcare providers facing the burden of adverse events: A systematic review of second victim support resources. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Baseline | Follow-Up 1 | Follow-Up 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 240 | n = 409 | n = 219 | |

| Age category (years) | |||

| 18–29 | 31 (12.9%) | 47 (11.5%) | 15 (6.8%) |

| 30–44 | 82 (34.2%) | 114 (27.9%) | 74 (33.8%) |

| 45–64 | 104 (43.3%) | 161 (39.4%) | 86 (39.3%) |

| 65 and older | 14 (5.8%) | 28 (6.8%) | 17 (7.8%) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0%) | 38 (9.3%) | 14 (6.4%) |

| Prefer not to answer | 9 (3.8%) | 21 (5.1%) | 13 (5.9%) |

| Race category | |||

| White | 158 (65.8%) | 244 (59.7%) | 144 (65.8%) |

| African American | 35 (14.6%) | 61 (14.9%) | 28 (12.8%) |

| Asian | 9 (3.8%) | 7 (1.7%) | 1 (0.5%) |

| Native Hawaiian | 1 (0.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 1 (0.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.5%) |

| Multiple Races | 7 (2.9%) | 3 (0.7%) | 1 (0.5%) |

| Prefer not to answer | 29 (12.1%) | 94 (23.0%) | 44 (20.1%) |

| Latino Ethnicity | |||

| No | 215 (89.6%) | 311 (76.0%) | 178 (81.3%) |

| Yes | 11 (4.6%) | 15 (3.7%) | 5 (2.3%) |

| Prefer not to answer | 14 (5.8%) | 45 (11.0%) | 21 (9.6%) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0%) | 38 (9.3%) | 15 (6.8%) |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 188 (78.3%) | 288 (70.4%) | 170 (77.6%) |

| Male | 35 (14.6%) | 49 (12.0%) | 18 (8.2%) |

| Trans | 1 (0.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Non-Binary | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (0.5%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Else | 1 (0.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Prefer to not Answer | 15 (6.2%) | 32 (7.8%) | 17 (7.8%) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0%) | 38 (9.3%) | 14 (6.4%) |

| Sexual Orientation | |||

| Gay/Lesbian | 9 (3.8%) | 5 (1.2%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Straight | 211 (87.9%) | 318 (77.8%) | 177 (80.8%) |

| Bisexual | 4 (1.7%) | 4 (1.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Other | 1 (0.4%) | 1 (0.2%) | 1 (0.5%) |

| Prefer not to answer | 15 (6.2%) | 42 (10.3%) | 25 (11.4%) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0%) | 39 (9.5%) | 16 (7.3%) |

| Employment Duration | |||

| <1 year | 33 (13.8%) | 41 (10.0%) | 13 (5.9%) |

| 1–2 years | 35 (14.6%) | 48 (11.7%) | 26 (11.9%) |

| 3–5 years | 43 (17.9%) | 65 (15.9%) | 37 (16.9%) |

| 6–10 years | 42 (17.5%) | 62 (15.2%) | 35 (16.0%) |

| >10 years | 80 (33.3%) | 133 (32.5%) | 83 (37.9%) |

| Prefer not to answer | 7 (2.9%) | 22 (5.4%) | 11 (5.0%) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0%) | 38 (9.3%) | 14 (6.4%) |

| Position | |||

| Clinician/Provider | 89 (37.1%) | 125 (30.6%) | 71 (32.4%) |

| Technician/Therapist | 63 (26.2%) | 94 (23.0%) | 63 (28.8%) |

| Leadership/Administration | 19 (7.9%) | 27 (6.6%) | 14 (6.4%) |

| Receptionist/Office Assistant | 22 (9.2%) | 31 (7.6%) | 20 (9.1%) |

| Other/Non-patient Contact | 28 (11.7%) | 42 (10.3%) | 12 (5.5%) |

| Missing | 19 (7.9%) | 90 (22.0%) | 39 (17.8%) |

| Anxiety Score | Burnout Score | Resilience Score | Culture of Well-Being Total Score | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated Slope | 95% Confidence Interval | Estimated Slope | 95% Confidence Interval | Estimated Slope | 95% Confidence Interval | Estimated Slope | 95% Confidence Interval | |

| Follow-up Time | ||||||||

| Time 1 vs. Baseline | −0.479 | [−1.277,0.319] | −0.270 | [−0.762,0.223] | 0.958 *** | [0.710,1.206] | 1.675 * | [0.0237,3.326] |

| Time 2 vs. Baseline | −1.077 * | [−2.084,−0.0705] | −0.807 * | [−1.469,−0.144] | 0.0415 | [−0.301,0.384] | 4.585 *** | [2.385,6.785] |

| Site | ||||||||

| SRH vs. Bayhealth | 0.306 | [−0.479,1.091] | 0.663 * | [0.155,1.170] | −0.0640 | [−0.421,0.293] | −3.934 *** | [−5.648,−2.219] |

| Interaction Term | ||||||||

| Time 1 × SRH | −0.859 *** | [−1.285,−0.433] | ||||||

| Employment Duration @ | ||||||||

| 1–2 years vs. <1 year | 1.068 | [−0.292,2.428] | 1.139 ** | [0.305,1.974] | −0.0701 | [−0.455,0.315] | −3.052 * | [−6.092,−0.0118] |

| 3–5 years vs. <1 year | 1.705 ** | [0.410,2.999] | 1.550 *** | [0.773,2.326] | −0.254 | [−0.614,0.106] | −4.461 ** | [−7.334,−1.589] |

| 6–10 years vs. <1 year | 1.424 * | [0.0602,2.789] | 1.621 *** | [0.857,2.386] | −0.171 | [−0.538,0.196] | −3.750 * | [−6.636,−0.864] |

| >10 years vs. <1 year | 0.909 | [−0.277,2.095] | 1.339 *** | [0.613,2.065] | 0.0944 | [−0.251,0.440] | −2.613 | [−5.355,0.129] |

| Age # | ||||||||

| 30–44 vs. 18–29 | −0.807 | [−2.050,0.436] | −0.539 | [−1.317,0.239] | −0.0713 | [−0.379,0.237] | −1.360 | [−3.753,1.033] |

| 45–64 vs. 18–29 | −2.092 ** | [−3.345,−0.839] | −1.222 ** | [−2.005,−0.439] | 0.122 | [−0.190,0.434] | −0.0776 | [−2.494,2.339] |

| 65 and older vs. 18–29 | −2.032 * | [−3.735,−0.330] | −1.456 ** | [−2.462,−0.451] | 0.104 | [−0.310,0.519] | 1.486 | [−1.633,4.605] |

| Intercept | 4.933 *** | [3.552,6.313] | 5.450 *** | [4.650,6.250] | 6.745 *** | [6.362,7.127] | 42.00 *** | [39.51,44.48] |

| F statistic (p-value) | F(10, 742) = 3.64 (<0.001) | F(10, 742) = 4.33 (<0.001) | F(11, 741) = 12.94 (<0.001) | F(10, 742) = 4.44 (<0.001) | ||||

| R-squared | 0.043 | 0.049 | 0.121 | 0.057 | ||||

| Observations | 753 | 753 | 753 | 753 | ||||

| Anxiety a | Burnout b | Low Resilience c | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | Estimated Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | Estimated Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | |

| Follow-up Time | ||||||

| Time 1 vs. Baseline | 0.831 | [0.583,1.184] | 0.850 | [0.586,1.233] | 0.376 * | [0.176,0.804] |

| Time 2 vs. Baseline | 0.664 | [0.412,1.069] | 0.630 | [0.383,1.036] | 1.338 | [0.589,3.041] |

| Site | ||||||

| SRH vs. Bayhealth | 1.333 | [0.929,1.912] | 1.350 | [0.931,1.957] | 0.877 | [0.375,2.046] |

| Interaction Term | ||||||

| Time 1 × SRH | 3.183 * | [1.004,10.09] | ||||

| Employment Duration | ||||||

| 1–2 years vs. <1 year | 1.468 | [0.800,2.695] | 1.199 | [0.595,2.414] | 0.931 | [0.393,2.204] |

| 3–5 years vs. <1 year | 2.046 * | [1.137,3.683] | 2.563 ** | [1.348,4.875] | 1.112 | [0.504,2.454] |

| 6–10 years vs. <1 year | 1.529 | [0.834,2.801] | 2.386 * | [1.222,4.656] | 0.985 | [0.432,2.247] |

| >10 years vs. <1 year | 1.656 | [0.934,2.939] | 2.053 * | [1.076,3.916] | 0.567 | [0.255,1.263] |

| Age | ||||||

| 30–44 vs. 18–29 | 0.807 | [0.481,1.354] | 0.732 | [0.426,1.256] | 1.245 | [0.598,2.591] |

| 45–64 vs. 18–29 | 0.397 *** | [0.232,0.676] | 0.423 ** | [0.239,0.748] | 1.001 | [0.472,2.124] |

| 65 and older vs. 18–29 | 0.446 * | [0.213,0.933] | 0.385 * | [0.174,0.855] | 1.223 | [0.414,3.614] |

| Intercept | 753 | 753 | 753 | |||

| AIC | 998.9 | 912.1 | 568.9 | |||

| Outcome | Baseline (n = 240) Mean (SD) | Follow-Up 1 (n = 409) Mean (SD) | Follow-Up 2 (n = 219) Mean (SD) | Cohen’s d Baseline vs. F/U 1 | Cohen’s d Baseline vs. F/U 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAD-7 Anxiety Score | 4.65 (4.93) | 4.28 (4.61) | 4.11 (4.49) | 0.08 | 0.12 |

| MBI-2 Burnout Score | 5.98 (2.87) | 5.94 (3.01) | 5.88 (2.92) | 0.01 | 0.04 |

| CD-RISC-2 Resilience Score | 6.70 (1.30) | 7.23 (1.21) | 6.71 (1.24) | −0.42 | −0.01 |

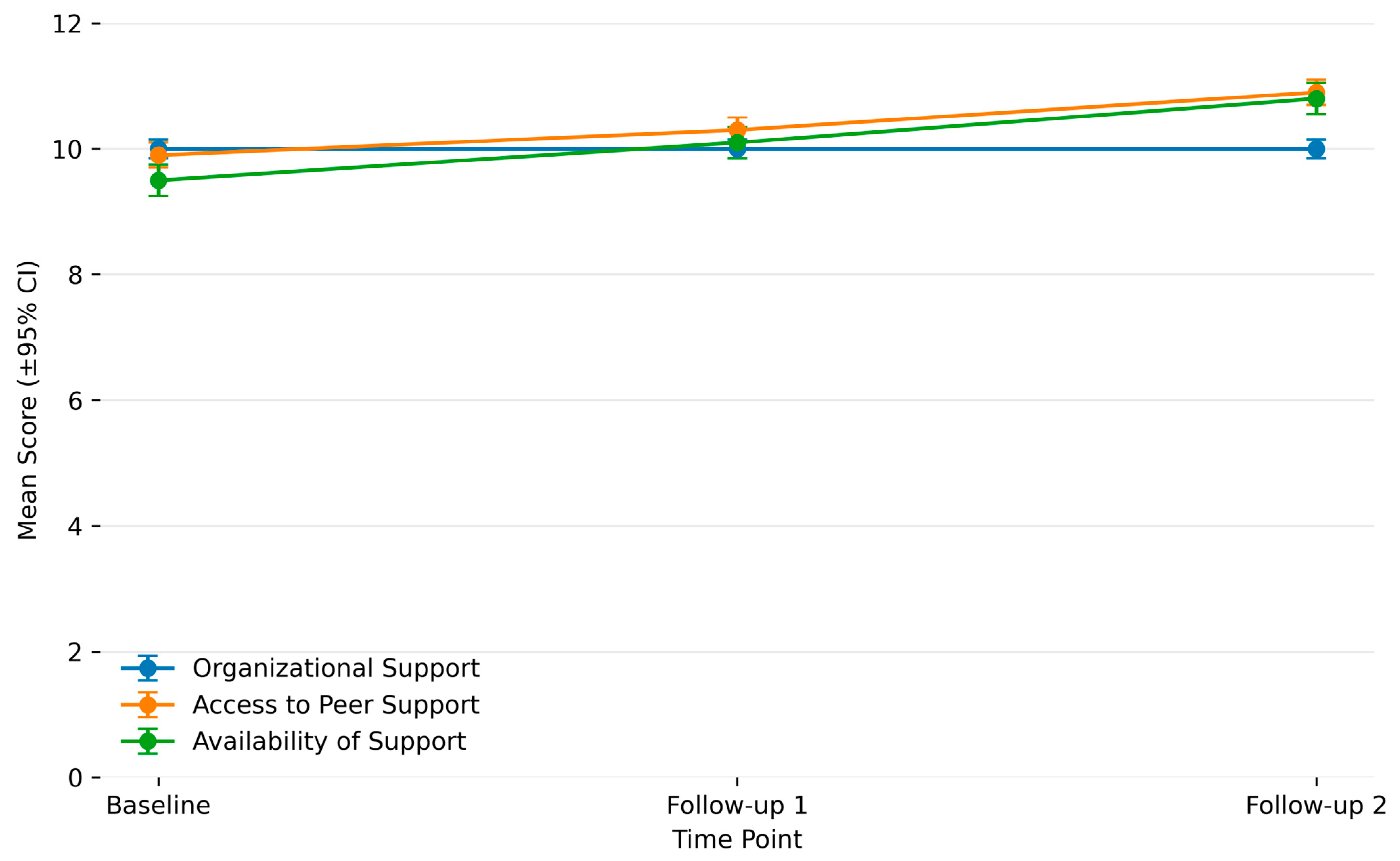

| Organizational Support | 9.03 (2.04) | 9.15 (2.33) | 8.97 (2.05) | −0.05 | 0.03 |

| Access to Peer Support | 9.80 (3.60) | 10.40 (3.67) | 10.86 (3.36) | −0.16 | −0.30 |

| Availability of Support | 18.48 (5.68) | 18.57 (5.92) | 18.89 (5.64) | −0.02 | −0.07 |

| Culture of Well-Being (Total) | 37.31 (9.60) | 37.67 (10.95) | 38.40 (9.86) | −0.03 | −0.11 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Malik, M.; Yenokyan, G.; Michtalik, H.; Miller, J.; Connors, C.; Weston, C.M.; Weeks, K.; Hu, W.; Norvell, M.; Wu, A.W. Strengthening the Culture of Well-Being in Rural Hospitals Through RISE Peer Support. Healthcare 2026, 14, 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010091

Malik M, Yenokyan G, Michtalik H, Miller J, Connors C, Weston CM, Weeks K, Hu W, Norvell M, Wu AW. Strengthening the Culture of Well-Being in Rural Hospitals Through RISE Peer Support. Healthcare. 2026; 14(1):91. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010091

Chicago/Turabian StyleMalik, Mansoor, Gayane Yenokyan, Henry Michtalik, Jane Miller, Cheryl Connors, Christine M. Weston, Kristina Weeks, William Hu, Matt Norvell, and Albert W. Wu. 2026. "Strengthening the Culture of Well-Being in Rural Hospitals Through RISE Peer Support" Healthcare 14, no. 1: 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010091

APA StyleMalik, M., Yenokyan, G., Michtalik, H., Miller, J., Connors, C., Weston, C. M., Weeks, K., Hu, W., Norvell, M., & Wu, A. W. (2026). Strengthening the Culture of Well-Being in Rural Hospitals Through RISE Peer Support. Healthcare, 14(1), 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010091