Impact of Social Media on HPV Vaccine Knowledge and Attitudes Among Adolescents and Young Adults: A Systematic Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

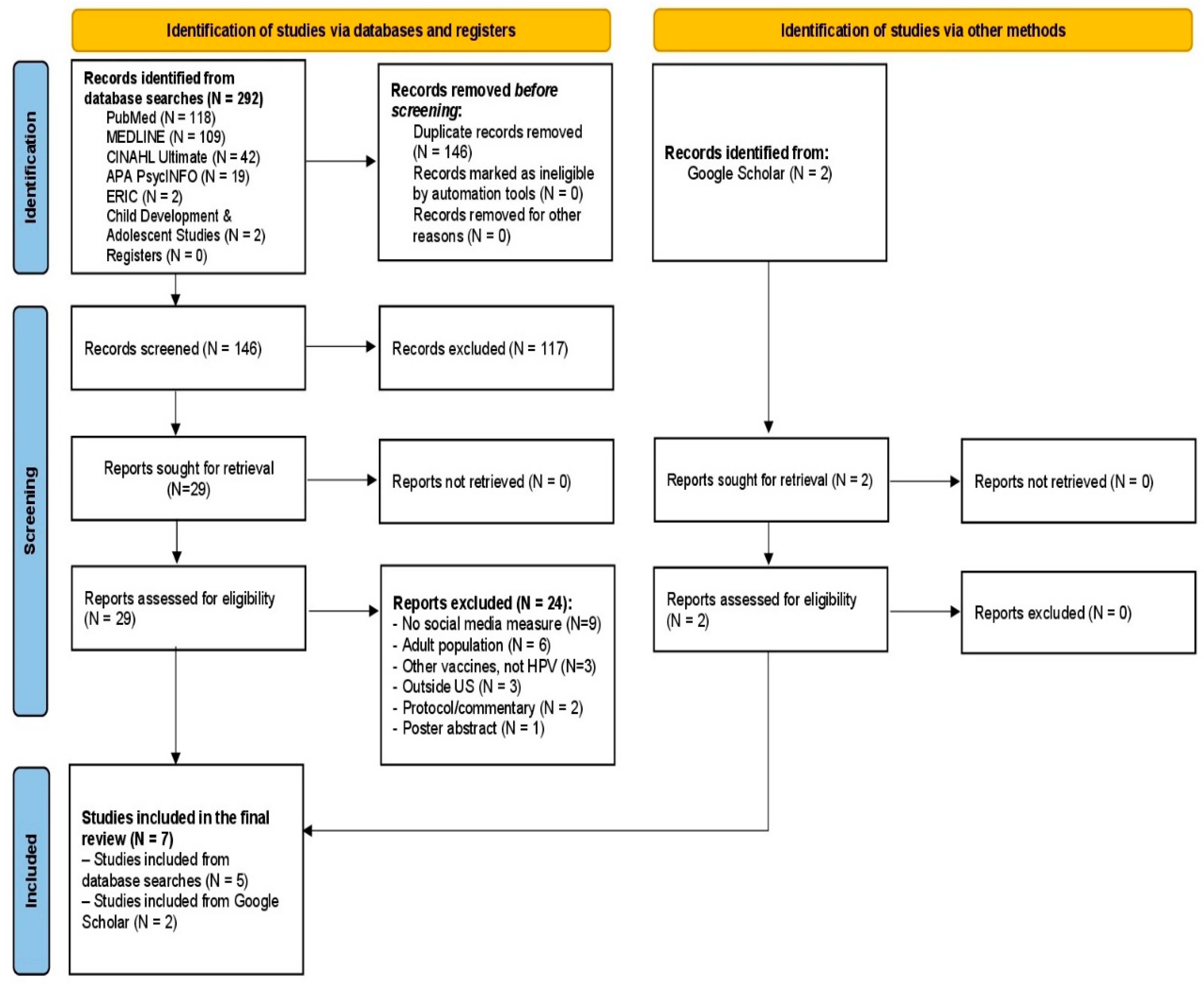

2. Materials and Methods

Quality Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Knowledge of HPV and the Role of Social Media

3.2. Perception of HPV and Vaccine Efficacy

3.3. Attitudes and Behavioral Intentions Toward HPV Vaccination

3.4. Risk of Bias Across Studies

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hirth, J. Disparities in HPV vaccination rates and HPV prevalence in the United States: A review of the literature. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2019, 15, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymonowicz, K.A.; Chen, J. Biological and clinical aspects of HPV-related cancers. Cancer Biol. Med. 2020, 17, 864–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, R.M.; Laprise, J.F.; Gargano, J.W.; Unger, E.R.; Querec, T.D.; Chesson, H.W.; Brisson, M.; Markowitz, L.E. Estimated prevalence and incidence of disease-associated human papillomavirus types among 15-to 59-year-olds in the United States. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2021, 48, 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About HPV. CDC Website; Updated 3 July 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/hpv/about/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/hpv/parents/about-hpv.html (accessed on 11 July 2024).

- Lehtinen, M.; Paavonen, J.; Wheeler, C.M.; Jaisamrarn, U.; Garland, S.M.; Castellsagué, X.; Skinner, R.; Apter, D.; Naud, P.; Salmerón, J.; et al. Overall efficacy of HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine against grade 3 or greater cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: 4-year end-of-study analysis of the randomised, double-blind PATRICIA trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012, 13, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, N.; Kjaer, S.K.; Sigurdsson, K.; Iversen, O.-E.; Hernandez-Avila, M.; Wheeler, C.M.; Perez, G.; Brown, D.R.; Koutsky, L.A.; Tay, E.H.; et al. Impact of human papillomavirus (HPV)-6/11/16/18 vaccine on all HPV-associated genital diseases in young women. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2010, 102, 325–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HPV Vaccination. CDC Website; Updated 20 August 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/hpv/vaccines/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/hpv/public/index.html (accessed on 30 November 2024).

- Meites, E.; Kempe, A.; Markowitz, L.E. Use of a 2-dose schedule for human papillomavirus vaccination—Updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2016, 65, 1405–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meites, E.; Szilagyi, P.G.; Chesson, H.W.; Unger, E.R.; Romero, J.R.; Markowitz, L.E. Human papillomavirus vaccination for adults: Updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2019, 68, 698–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.Y.; Lee, J.; Henning-Smith, C.; Choi, J. HPV literacy and its link to initiation and completion of HPV vaccine among young adults in Minnesota. Public Health 2017, 152, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pingali, C.; Yankey, D.; Elam-Evans, L.D.; Markowitz, L.E.; Valier, M.R.; Fredua, B.; Crowe, S.J.; Stokley, S.; Singleton, J.A. National vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years—National Immunization Survey-Teen, United States, 2021. MMWR Morb. Mortal Wkly. Rep. 2022, 71, 1101–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, S.A.; Mullen, P.D.; Lopez, D.M.; Savas, L.S.; Fernandez, M.E. Factors associated with adolescent HPV vaccination in the US: A systematic review of reviews and multilevel framework to inform intervention development. Prev. Med. 2019, 131, 105968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, R.R.; Smith, A.; Coyne-Beasley, T. A systematic literature review to examine the potential for social media to impact HPV vaccine uptake and awareness, knowledge, and attitudes about HPV and HPV vaccination. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2019, 15, 1465–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyris, Y.A.; Kim, Y.; Roscizewski, A.; Song, W. The mediating role of vaccine hesitancy between maternal engagement with anti-and pro-vaccine social media posts and adolescent HPV-vaccine uptake rates in the US: The perspective of loss aversion in emotion-laden decision circumstances. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 282, 114043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, S.; Duggan, M. Mobile Health 2012; Pew Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; Available online: http://www.pewinternet.org/2012/11/08/mobile-health-2012/ (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Wartella, E.; Rideout, V.; Montague, H.; Beaudoin-Ryan, L.; Lauricella, A. Teens, health and technology: A national survey. Media Commun. 2015, 4, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faverio, M.; Sidoti, O.; Atske, S.; Park, E. Teens and Social Media Fact Sheet; Pew Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/teens-and-social-media-fact-sheet/ (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Faverio, M.; Sidoti, O.; Atske, S.; Park, E. Teens and Internet, Device Access Fact Sheet. Pew Research Center Published 5 January 2024. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/teens-and-internet-device-access-fact-sheet/ (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Glenn, B.A.; Nonzee, N.; Tieu, L.; Pedone, B.; Cowgill, B.O.; Bastani, R. Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination in the transition between adolescence and adulthood. Vaccine 2021, 39, 4350–4358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veritas Health Innovation. Covidence Systematic Review Software; Veritas Health Innovation: Melbourne, Australia, 2024; Available online: www.covidence.org (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Ortiz, R.R.; Shafer, A.; Cates, J.; Coyne-Beasley, T. Development and evaluation of a social media health intervention to improve adolescents’ knowledge about and vaccination against the human papillomavirus. Glob. Pediatr. Health 2018, 5, 2333794X18777918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, X.; Daily, K. Biased assimilation and need for closure: Examining the effects of mixed blogs on vaccine-related beliefs. J. Health Commun. 2015, 20, 462–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.C.; Vraga, E.K.; Cook, J. An eye tracking approach to understanding misinformation and correction strategies on social media: The mediating role of attention and credibility to reduce HPV vaccine misperceptions. Health Commun. 2021, 36, 1687–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.J.; Cho, J. Promoting HPV vaccination online: Message design and media choice. Health Promot. Pract. 2017, 18, 645–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leader, A.E.; Miller-Day, M.; Rey, R.T.; Selvan, P.; Pezalla, A.E.; Hecht, M.L. The impact of HPV vaccine narratives on social media: Testing narrative engagement theory with a diverse sample of young adults. Prev. Med. Rep. 2022, 29, 101920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.D.; Hollander, J.; Gualtieri, L.; Alarcon Falconi, T.M.; Savir, S.; Agénor, M. Feasibility of a twitter campaign to promote HPV vaccine uptake among racially/ethnically diverse young adult women living in public housing. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohanty, S.; Leader, A.E.; Gibeau, E.; Johnson, C. Using Facebook to reach adolescents for human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination. Vaccine 2018, 36, 5955–5961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.-Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Hernán, M.A.; Reeves, B.C.; Savović, J.; Berkman, N.D.; Viswanathan, M.; Henry, D.; Altman, D.G.; Ansari, M.T.; Boutron, I.; et al. ROBINS-I: A tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomized studies of interventions. BMJ 2016, 355, i4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lama, Y.; Quinn, S.; Nan, X.; Cruz-Cano, R. Social media use and human papillomavirus awareness and knowledge among adults with children in the household: Examining the role of race, ethnicity, and gender. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2020, 17, 1014–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, S.; Pituch, K.; Howe, N. The Relationships Between Social Media and Human Papillomavirus Awareness and Knowledge: Cross-sectional Study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2022, 8, e37274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adegboyega, A.; Wiggins, A.; Wuni, A.; Ickes, M. The Impact of a Human Papillomavirus Facebook-Based Intervention (#HPVVaxTalks) Among Young Black (African American and Sub-Saharan African Immigrants) Adults: Pilot Pre- and Poststudy. JMIR Form. Res. 2025, 9, e69609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boatman, D.; Jarrett, Z.; Starkey, A.; Conn, M.E.; Kennedy-Rea, S. HPV vaccine misinformation on social media: A multi-method qualitative analysis of comments across three platforms. PEC Innov. 2024, 5, 100329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luisi, M.L.R. From bad to worse: The representation of the HPV vaccine Facebook. Vaccine 2020, 38, 4564–4573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, Y.; Young, R.; Wu, X.; Zhu, G. Effects of Vaccine-Related Conspiracy Theories on Chinese Young Adults’ Perceptions of the HPV Vaccine: An Experimental Study. Health Commun. 2021, 36, 1343–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burki, T. The online anti-vaccine movement in the age of COVID-19. Lancet Digit. Health 2020, 2, e504–e505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandt, H.; Sundstrom, B.; Monroe, C.; Turner-McGrievy, G.; Larsen, C.; Stansbury, M.; Magradey, K.; Gibson, A.; West, D. Evaluating a Technology-Mediated HPV Vaccination Awareness Intervention: A Controlled, Quasi-Experimental, Mixed Methods Study. Vaccines 2020, 8, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balatsoukas, P.; Kennedy, C.; Buchan, I.; Powell, J.; Ainsworth, J. The role of social network technologies in online health promotion: A narrative review of theoretical and empirical factors influencing intervention effectiveness. J. Med. Internet Res. 2015, 17, e141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihm, J.; Lee, C. Toward more effective public health interventions during the COVID-19 pandemic: Suggesting audience segmentation based on social and media resources. Health Commun. 2020, 36, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takagi, M.; Hess, S.; Smith, Z.; Gawronski, K.; Kumar, A.; Horsley, J.; Haddad, N.; Noveloso, B.; Zyzanski, S.; Ragina, N. The impact of educational interventions on COVID-19 and vaccination attitudes among patients in Michigan: A prospective study. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1144659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, A.; Patel, D.; Carlos, R.; Zochowski, M.K.; Pennewell, S.M.; Chi, A.M.; Dalton, V.K. Human papillomavirus vaccine uptake after a tailored, online educational intervention for female university students: A randomized controlled trial. J. Womens Health 2015, 24, 950–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadda, M.; Galimberti, E.; Fiordelli, M.; Romanò, L.; Zanetti, A.; Schulz, P. Effectiveness of a smartphone app to increase parents’ knowledge and empowerment in the MMR vaccination decision: A randomized controlled trial. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2017, 13, 2512–2521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donadiki, E.; Jiménez-García, R.; Hernández-Barrera, V.; Sourtzi, P.; Carrasco-Garrido, P.; Andrés, A.; Jiménez-Trujillo, I.; Velonakis, E. Health Belief Model applied to non-compliance with HPV vaccine among female university students. Public Health 2014, 128, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beavis, A.; Krakow, M.; Levinson, K.; Rositch, A. Reasons for Lack of HPV Vaccine Initiation in NIS-Teen Over Time: Shifting the Focus From Gender and Sexuality to Necessity and Safety. J. Adolesc. Health 2018, 63, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirayil, E.; Thompson, C.; Burney, S. Predicting Human Papilloma Virus Vaccination and Pap Smear Screening Intentions Among Young Singaporean Women Using the Theory of Planned Behavior. SAGE Open 2014, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Hu, J.; Gao, H.; Wang, S.; Wang, B.; Wang, J.; Li, H.; Wang, J.; Yuan, C.; Zhang, X. Long-term effect of mobile phone-based education and influencing factors of willingness to receive HPV vaccination among female freshmen in Shanxi Province, China. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2022, 18, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz, L.; Villarreal, D.; Marquez, K.; Scartascini, C. Combating vaccine hesitancy: The case of HPV vaccination. Soc. Sci. Med. 2025, 381, 118081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liebermann, E.; Kornides, M.; Matsunaga, M.; Lim, E.; Zimet, G.; Glauberman, G.; Kronen, C.; Fontenot, H. Use of social media and its influence on HPV vaccine hesitancy: US National Online Survey of mothers of adolescents, 2023. Vaccine 2024, 44, 126571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, E.L.; Preston, S.M.; Francis, J.K.R.; Rodriguez, S.A.; Pruitt, S.L.; Blackwell, J.M.; Tiro, J.A. Social Media Perceptions and Internet Verification Skills Associated With Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Decision-Making Among Parents of Children and Adolescents: Cross-sectional Survey. JMIR Pediatr. Parent. 2022, 5, e38297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Burke-Garcia, A.; Cutroneo, E.; Afanaseva, D.; Madden, K.; Sustaita-Ruiz, A.; Selvan, P.; Sanchez, E.; Leader, A. Findings from a qualitative analysis: Social media influencers of color as trusted messengers of HPV vaccination messages. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0319160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopfer, S.; Phillips, K.; Weinzierl, M.; Vasquez, H.; Alkhatib, S.; Harabagiu, S. Adaptation and Dissemination of a National Cancer Institute HPV Vaccine Evidence-Based Cancer Control Program to the Social Media Messaging Environment. Front. Digit. Health 2022, 4, 819228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, E.; Loft, L.; Jacobsen, S.; Søborg, B.; Bigaard, J. Strategic health communication on social media: Insights from a Danish social media campaign to address HPV vaccination hesitancy. Vaccine 2020, 38, 4909–4915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Li, K. Get Vaccinated for Loved Ones: Effects of Self-Other Appeal and Message Framing in Promoting HPV Vaccination among Heterosexual Young Men. Health Commun. 2021, 38, 381–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.; Su, L. When a Personal HPV Story on a Blog Influences Perceived Social Norms: The Roles of Personal Experience, Framing, Perceived Similarity, and Social Media Metrics. Health Commun. 2020, 35, 438–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Database | Concept | Search Term |

|---|---|---|

| ERIC, APA PsycInfo, Child Development & Adolescent Studies, CINAHL Ultimate, MEDLINE Ultimate | Social Media | (“social media” OR “social networking sites” OR “online platforms” OR Facebook OR Twitter OR Instagram OR TikTok OR YouTube) AND |

| Adolescents and Young Adults | (adolescen* OR teen* OR youth OR “young people” OR “high school student*” OR “secondary school student*”) AND | |

| HPV Vaccination | (“HPV vaccin*” OR “human papillomavirus vaccin*” OR “HPV immuniz*” OR “HPV vaccinat*”)AND | |

| Health Behavior | (awaren* OR knowledg* OR attitud* OR percept* OR belief* OR opinion* OR understand* OR information OR education) | |

| PUBMED | (((((“social media”[MeSH] OR “social media” OR “social networking sites” OR “online platforms” OR Facebook OR Twitter OR Instagram OR TikTok OR YouTube)) AND ((“adolescent”[MeSH] OR “youth”[MeSH] OR adolescen* OR teen* OR youth OR “young people” OR “high school student*” OR “secondary school student*”))) AND ((“papillomavirus vaccines”[MeSH] OR “HPV vaccin*” OR “human papillomavirus vaccin*” OR “HPV immuniz*” OR “HPV vaccinat*”))) AND ((“health knowledge, attitudes, practice”[MeSH] OR awaren* OR knowledg* OR attitud* OR percept* OR belief* OR opinion* OR understand* OR information OR education))) |

| No | Author (Year) | Purpose | Design | Sample/Population | Outcome Measure | Key Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Leader et al., (2022) [26] | To test whether social media narrative engagement variations led to differences in HPV vaccine intentions. | Experimental | Social media participants between the ages of 18 and 26 who had not received the HPV vaccine (n = 607) | Intention | There was also a positive relationship between social media engagement and intentions to vaccinate (r = 0.43, p = 0.01) |

| 2. | Mohanty et al., (2018) [28] | To assess the campaign reach, engagement, and HPV vaccine uptake among Philadelphia adolescents through the 3forME Facebook campaign | Quasi-experimental study | Adolescents with a Facebook account who self-identified as being between the ages of 13 and 18 years old and living in Philadelphia were targeted to receive a series of advertisements from 3forME Reach: (n = 155,110) Engagement: (n = 2107) | Vaccine uptake | The advertising campaigns did not have a strong effect on HPV vaccine uptake even when common barriers of parental consent and cost were minimized. |

| 3. | Allen et al., (2020) [27] | To assess the feasibility and preliminary effect of a month-long Twitter campaign among a low-income and racially/ethnically diverse group of women | Quasi- experimental study | Women aged 18 to 26 years who were residents of public housing in two Massachusetts cities (n = 35) | Knowledge, Intention | HPV vaccination knowledge scores were low and did not change after the campaign (56% vs. 57%, p = 0.858) No statistically significant change in the intent to be vaccinated in the next 6 months (p = 1.000) or 12 months (p = 0.617) after the campaign among those who had not yet started or completed vaccination |

| 4. | Kim et al., (2020) [24] | Measures how much attention audiences pay to misinformation and a correction message, and how attention is shaped by the correction strategy employed (humor versus non-humor) | Experimental | Students from a major mid- Atlantic University, over the age of 18, who could speak and understand English (n = 61) | Perception | Credibility ratings of the misinformation were positively associated with HPV misperceptions, while credibility ratings for the correction were negatively associated with HPV misperceptions |

| 5. | Nan & Daily (2015) [23] | To provide insight into the polarizing effects of mixed blogs on HPV vaccine-related beliefs, including perceived vaccine efficacy and safety | Experimental | Undergraduate students with a mean age of 20 from a large East Coast university (n = 338) | Perception | For participants who perceived vaccines, in general, to be ineffective, exposure to the mixed blogs slightly reduced perceived efficacy of the HPV vaccine. In contrast, for participants who perceived vaccines in general to be very efficacious, exposure to the mixed blogs increased perceived efficacy of the HPV vaccine. |

| 6. | Ortiz et al., (2018) [22] | To determine whether the strategic distribution of information about HPV and the HPV vaccine via an adolescent (ages 13–18) social media platform (i.e., Facebook) is a feasible and effective way to improve adolescents’ knowledge about the virus, vaccine, and vaccination rates. | Experimental | Adolescents with an average age of 15.6 years (SD = 1.68) participated in the final intervention (n = 108) | Knowledge, Attitude | Univariate tests revealed a significant within-subjects pretest to posttest difference between the four groups for knowledge gain, F(3, 103) = 2.76, p < 0.05, but not for vaccination rates, F(3, 103) = 1.10, p = 0.35. A post hoc analysis of the four groups indicated that for those participants in the intervention group who reported receiving a notification every time a new fact was posted to the Facebook page, they were significantly more likely than any other group to increase in their HPV and vaccine knowledge, p < 0.05. |

| 7. | Lee & Cho (2017) [25] | Investigated whether using different message framing and media influences the public’s perceived severity/benefits/barriers, and their willingness to get vaccinated | Experimental | College students between 20 and 28 years old (M = 22.44, SD = 1.22) (n = 142) | Perception, Behavioral intention | No significant difference between newspaper and Facebook in their effect on behavioral intentions (p = 0.94). However, loss-framed messages on Facebook led to higher vaccination intentions (M = 4.90, SD = 1.33) Discovered that media channels significantly affected perceived severity and barriers to HPV vaccination. Participants exposed to online newspapers perceived greater severity of HPV-related risks compared to those exposed to Facebook (M = 5.08 vs. 4.63, p < 0.05) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Apata, B.O.; Tupe, A.H.; Akeju, O.; Wilson, K.L. Impact of Social Media on HPV Vaccine Knowledge and Attitudes Among Adolescents and Young Adults: A Systematic Literature Review. Healthcare 2026, 14, 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010073

Apata BO, Tupe AH, Akeju O, Wilson KL. Impact of Social Media on HPV Vaccine Knowledge and Attitudes Among Adolescents and Young Adults: A Systematic Literature Review. Healthcare. 2026; 14(1):73. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010073

Chicago/Turabian StyleApata, Blessing Oluwatofunmi, Anagha Hemant Tupe, Oluwabusayomi Akeju, and Kelly L. Wilson. 2026. "Impact of Social Media on HPV Vaccine Knowledge and Attitudes Among Adolescents and Young Adults: A Systematic Literature Review" Healthcare 14, no. 1: 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010073

APA StyleApata, B. O., Tupe, A. H., Akeju, O., & Wilson, K. L. (2026). Impact of Social Media on HPV Vaccine Knowledge and Attitudes Among Adolescents and Young Adults: A Systematic Literature Review. Healthcare, 14(1), 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010073