The Utilization, Application, and Impact of Institutional Special Needs Plans (I-SNPs) in Nursing Facilities: A Rapid Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Rationale

1.2. Objectives

1.3. Population, Concept, and Context (PCC)

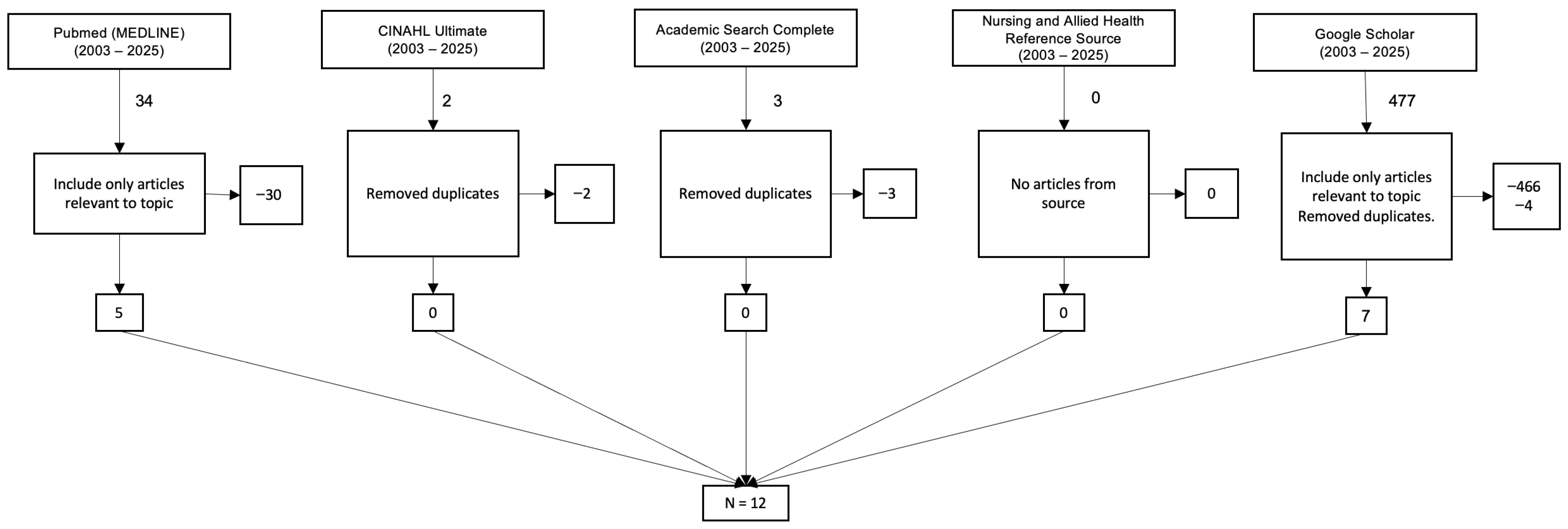

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

3. Results

3.1. Overview

3.2. Thematic Findings

3.2.1. Theme 1: Market Penetration and Enrollment (The Extent of Use)

3.2.2. Theme 2: The I-SNP Model of Care (The Application of Use)

- On-site Clinicians: The model’s foundation is the use of dedicated advanced practice clinicians, primarily Nurse Practitioners (NPs) and Physician Assistants (PAs), who are embedded within the nursing facility [4,8,13,14,16,18]. Some models refer to these clinicians as “NF-ists” (Nursing Facility-ists) [13].

- Proactive Management: The goal is proactive care management to identify and treat new conditions or symptoms (e.g., pain, depression, infection) early, thereby preventing clinical deterioration [4,6]. This involves improved communication among the plan, the facility staff, the resident, and their family [6]. Together, these elements reflect a high-touch clinical model distinct from traditional physician-driven care in nursing homes.

3.2.3. Theme 3: Impact of Utilization on Clinical and Financial Outcomes (The Effect of Use)

- Reduced Hospitalizations: A consistent finding across multiple studies is that I-SNP utilization is associated with significant reductions in avoidable hospitalizations and emergency department (ED) visits [4,6,12,14,16,18]. One major study found that I-SNP members had 38% fewer hospitalizations and 51% lower ED use compared to FFS beneficiaries [4,14]. Another analysis found that facilities with mature I-SNP penetration (high enrollment) experienced a 4.1 percentage point decline in hospitalizations [12,14,16,18].

- Mechanism of “Substitution”: The literature clearly identifies the mechanism for this reduction: substitution. I-SNP models use on-site skilled nursing care in place of hospital care [13]. This is enabled by a crucial policy feature: the waiver of the 3-day qualifying hospital stay requirement [4,14,16,18]. This allows NPs/PAs to provide and bill for skilled services within the facility. This explains the finding that I-SNP members had 112% higher SNF utilization—delivered within their existing facility rather than after hospitalization [4].

- Mixed Clinical Outcomes: While the impact on hospitalizations is clear, the evidence for other clinical outcomes is nuanced and complex. One large-scale study found that I-SNP maturity was associated with positive outcomes (fewer pressure ulcers, fewer urinary tract infections) [14,16]. However, the same study found associations with negative outcomes: increased need for help with Activities of Daily Living (ADLs), increased use of antipsychotics, and more falls [12]. For residents with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD), reduced acute care use could generate an estimated $1.2 billion in annual savings through lower hospitalization rates [18].

3.2.4. Theme 4: Barriers to Utilization (The Limits of Use)

- Payer and Provider Reluctance: Utilization is limited because some MA organizations (payers) may not want to contract with all NFs, and some NFs (providers) may not wish to participate in an I-SNP network [3]. Nearly 70 percent of nursing homes did not have any residents enrolled in I-SNPs [14]. I-SNPs were also not available for enrollment in more than 60 percent of counties in the United States [14].

- Negative clinical outcomes: An increase of 5.3 pp in the need for help with activities of daily living may suggest a decline in residents’ functional ability and increased dependence for those enrolled in these plans [16]. There are also small increases in the use of antipsychotic medications (1.3 pp), falls (1.0 pp), and the use of physical restraints (1.0 pp) [16]. I-SNP enrollment was also associated with greater use of lower-rated hospice providers [15].

4. Discussion

4.1. The I-SNP Substitution Model

4.2. The “Mixed Outcomes” Conundrum

- Surveillance and Documentation Bias: The presence of on-site, dedicated NPs [4,13] likely results in superior identification and documentation of these conditions (falls, ADL changes) compared to FFS residents, who may only be seen by a physician intermittently. This would make the I-SNP group appear to have worse outcomes, when in fact their care is simply more closely monitored.

4.3. Gaps in the Literature

- Resident and family satisfaction with I-SNP models.

- The effectiveness of different MOCs (e.g., staffing ratios, NP vs. PA, “NF-ist” model).

- Longitudinal studies that can untangle the “mixed outcomes” finding (e.g., to test the surveillance bias hypothesis).

- Qualitative research exploring the facility-level barriers to adoption [3].

5. Conclusions

Implications for Policy and Practice

6. Study Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Health Care Services; Committee on the Quality of Care in Nursing Homes. The National Imperative to Improve Nursing Home Quality: Honoring Our Commitment to Residents, Families, and Staff; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2022; ISBN 978-0-309-68628-0. [Google Scholar]

- Grabowski, D.C.; Chen, A.; Saliba, D. Paying for Nursing Home Quality: An Elusive But Important Goal. Public. Policy Aging Rep. 2023, 33, S22–S27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MedPAC. Chapter 5: Medicare Beneficiaries in Nursing Homes (June 2025 Report); MedPAC: Washington, DC, USA, 2025.

- McGarry, B.E.; Grabowski, D.C. Managed Care for Long-Stay Nursing Home Residents: An Evaluation of Institutional Special Needs Plans. Am. J. Manag. Care 2019, 25, 438–443. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Special Needs Plans (SNP)|Medicare. Available online: https://www.cms.gov/medicare/enrollment-renewal/special-needs-plans (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Great Plains Medicare Advantage. Model of Care; Great Plains Medicare Advantage: Sioux Falls, SD, USA, 2020.

- Yeh, M.; Yen, I. Institutional Special Needs Plans: 2024 Market Landscape and Future Considerations. Available online: https://www.milliman.com/en/insight/institutional-special-needs-plans-2024-market-landscape-future (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Singletary, E.; Roiland, R.; Harker, M.; Taylor, D.; Saunders, R. Value Based Payment and Skilled Nursing Facilities: Supporting SNFs During COVID-19 and Beyond; Duke-Margolis Institute for Health Policy: Durham, NC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Moher, D. Updating Guidance for Reporting Systematic Reviews: Development of the PRISMA 2020 Statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2021, 134, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruse, C.S. Writing a Systematic Review for Publication in a Health-Related Degree Program. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2019, 8, e15490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhingra, L.; Lipson, K.; Dieckmann, N.F.; Chen, J.; Bookbinder, M.; Portenoy, R. Institutional Special Needs Plans and Hospice Enrollment in Nursing Homes: A National Analysis. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2019, 67, 2537–2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Signature Advantage. Signature Advantage Advantage Plan & Signature Advantage Community (HMO ISNP) Provider Manual 2021. Available online: https://signatureadvantageplan.com/wp-content/uploads/documents/2021/2021%20Provider%20Manual%20Final.pdf (accessed on 23 December 2025).

- Chen, A.C.; Hnath, J.G.P.; Grabowski, D.C. Institutional Special Needs Plans In Nursing Homes: Substantial Enrollment Growth But Low Availability, 2006–21. Health Aff. 2024, 43, 1384–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, L.L.Y.; Sun, C.; Coe, N.B. Quality of Hospices Used by Medicare Advantage and Traditional Fee-for-Service Beneficiaries. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2451227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, A.C.; Grabowski, D.C. A Model to Increase Care Delivery in Nursing Homes: The Role of Institutional Special Needs Plans. Health Serv. Res. 2025, 60, e14390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yun, H.; Rahman, M.; McGarry, B.; White, E.M.; Meyers, D.J.; Kosar, C.M. Disenrollment from Special Needs and Other Medicare Advantage Plans Among Nursing Home Residents. JAMA Netw. Open 2025, 8, e2523973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, M.; McGarry, B.; White, E.M.; Grabowski, D.C.; Kosar, C.M. Is Managed Care Effective in Long-Term Care Settings? Evidence from Medicare Institutional Special Needs Plans; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

| Year | Author | Strength | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | Dhingra et al. [12] | II | A |

| 2019 | McGarry and Grabowski [4] | II | A |

| 2020 | Great Plains Medicare Advantage [6] | IV | B |

| 2021 | Singletary et al. [8] | II | A |

| 2021 | Signature Advantage [13] | IV | B |

| 2024 | Chen et al. [14] | III | A |

| 2024 | Yeh and Yen [7] | II | A |

| 2024 | White et al. [15] | II | A |

| 2025 | Chen and Grabowski [16] | II | A |

| 2025 | Yun et al. [17] | II | A |

| 2025 | Rahman et al. [18] | IV | B |

| 2025 | MedPAC [3] | IV | B |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mileski, M.; Shapley, R.; Beauvais, B.; Topinka, J.B.; Shanmugam, R.; Betancourt, J.A.; Brooks, M.; McClay, R. The Utilization, Application, and Impact of Institutional Special Needs Plans (I-SNPs) in Nursing Facilities: A Rapid Review. Healthcare 2026, 14, 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010071

Mileski M, Shapley R, Beauvais B, Topinka JB, Shanmugam R, Betancourt JA, Brooks M, McClay R. The Utilization, Application, and Impact of Institutional Special Needs Plans (I-SNPs) in Nursing Facilities: A Rapid Review. Healthcare. 2026; 14(1):71. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010071

Chicago/Turabian StyleMileski, Michael, Roland Shapley, Bradley Beauvais, Joseph Baar Topinka, Ramalingam Shanmugam, Jose A. Betancourt, Matthew Brooks, and Rebecca McClay. 2026. "The Utilization, Application, and Impact of Institutional Special Needs Plans (I-SNPs) in Nursing Facilities: A Rapid Review" Healthcare 14, no. 1: 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010071

APA StyleMileski, M., Shapley, R., Beauvais, B., Topinka, J. B., Shanmugam, R., Betancourt, J. A., Brooks, M., & McClay, R. (2026). The Utilization, Application, and Impact of Institutional Special Needs Plans (I-SNPs) in Nursing Facilities: A Rapid Review. Healthcare, 14(1), 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010071