The Contribution of Yoga to the Psychosocial Rehabilitation and Social Reintegration of Incarcerated Individuals: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

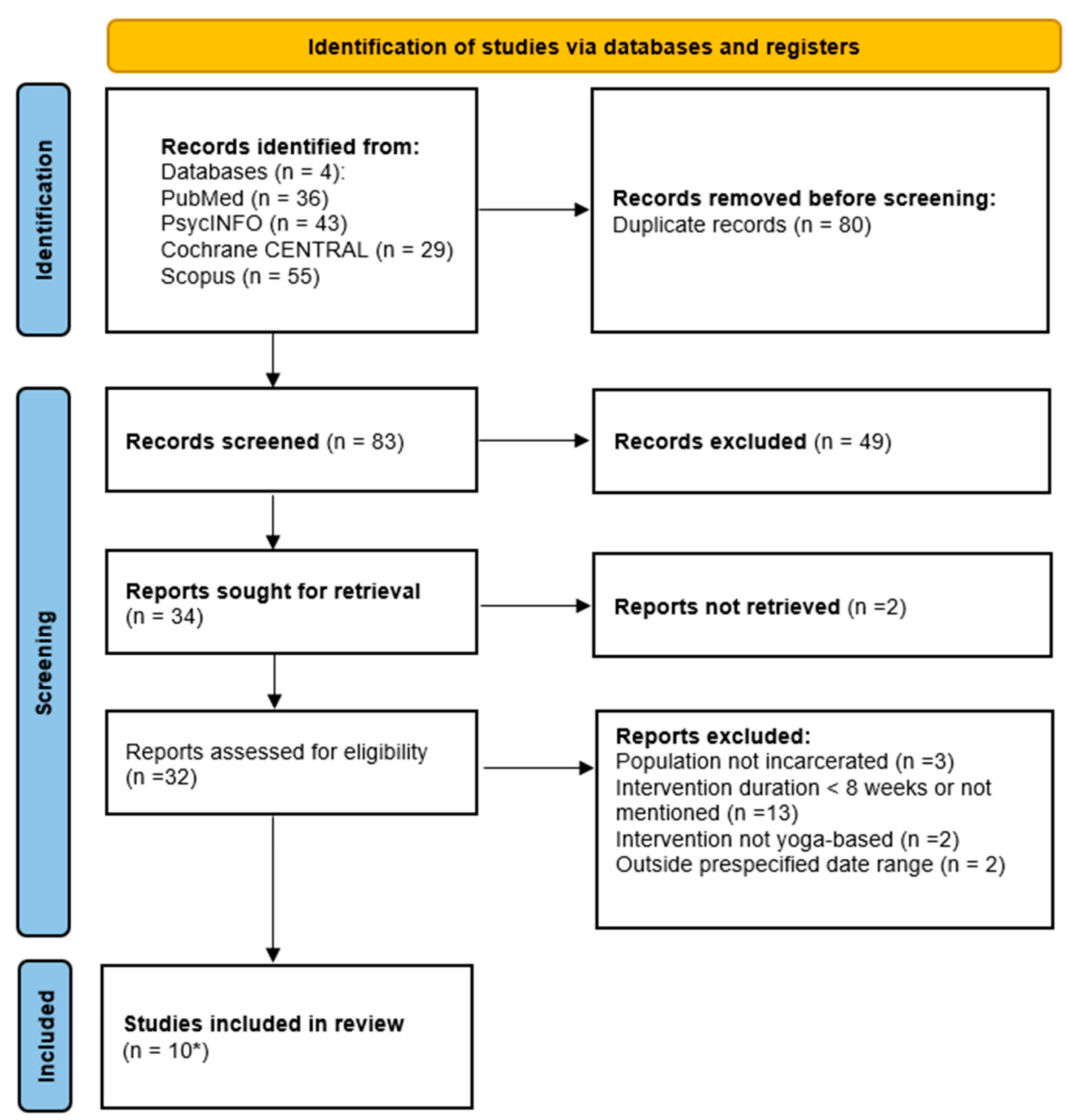

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Screening Process

2.4. Data Extraction and Appraisal

2.5. Theoretical and Analytical Framework

2.6. Data Synthesis Strategy

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.2. Psychological Distress, Mood, and General Psychosocial Functioning

3.3. Trauma-Related Symptoms, Mindfulness, and Resilience

3.4. Emotional Regulation, Anger, and Aggression

3.5. Youth and Gender-Responsive Interventions

3.6. Institutional and Post-Release Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jäggi, L.J.; Mezuk, B.; Watkins, D.C.; Jackson, J.S. The Relationship between Trauma, Arrest, and Incarceration History among Black Americans. Soc. Ment. Health 2016, 6, 187–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emilian, C.; Al-Juffali, N.; Fazel, S. Prevalence of Severe Mental Illness among People in Prison across 43 Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Lancet Public Health 2025, 10, e97–e110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazher, S.; Arai, T. Behind Bars: A Trauma-Informed Examination of Mental Health through Importation and Deprivation Models in Prisons. Eur. J. Trauma Dissociation 2025, 9, 100516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, N.A.; Najavits, L.M. Creating Trauma-Informed Correctional Care: A Balance of Goals and Environment. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2012, 3, 17246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazel, S.; Hayes, A.J.; Bartellas, K.; Clerici, M.; Trestman, R. Mental Health of Prisoners: Prevalence, Adverse Outcomes, and Interventions. Lancet Psychiatry 2016, 3, 871–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazel, S.; Seewald, K. Severe Mental Illness in 33 588 Prisoners Worldwide: Systematic Review and Meta-Regression Analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry 2012, 200, 364–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaudry, G.; Yu, R.; Långström, N.; Fazel, S. An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Regression Analysis: Mental Disorders Among Adolescents in Juvenile Detention and Correctional Facilities. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2021, 60, 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livanou, M.; Furtado, V.; Singh, S. Prevalence and Nature of Mental Disorders Among Young Offenders in Custody and Community: A Meta-Analysis. Eur. Psychiatry 2016, 33, S460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Op den Kelder, R.; Van den Akker, A.L.; Geurts, H.M.; Lindauer, R.J.L.; Overbeek, G. Executive Functions in Trauma-Exposed Youth: A Meta-Analysis. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2018, 9, 1450595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liddle, M.; Boswell, G.; Wright, S.; Francis, V.; Perry, R. Trauma and Young Offenders, A Review of the Research and Practice Literature; Beyond Youth Custody: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, N.; Facer-Irwin, E.; Dickson, H.; Bird, A.; MacManus, D. The Effectiveness of Trauma-Focused Interventions in Prison Settings: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Trauma Violence Abus. 2023, 24, 844–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gueta, K.; Chen, G.; Ronel, N. Trauma-Oriented Recovery Framework with Offenders: A Necessary Missing Link in Offenders’ Rehabilitation. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2022, 63, 101678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dent, H.; Nielsen, K.; Ward, T. Correctional Rehabilitation and Human Functioning: An Embodied, Embedded, and Enactive Approach. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2020, 51, 101383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaber, J.; Scallan, E.; Kouyoumdjian, F.G. Understanding Trauma-Informed Care in Correctional Facilities: A Scoping Review. J. Correct. Health Care 2025, 31, 144–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Feng, V.N.; Ramirez, M.; Behrens, K.L.; Usset, T.; Claussen, A.M.; Parikh, R.R.; Lee, E.K.; Mendenhall, T.; Wilt, T.J.; Butler, M. Trauma Informed Care: A Systematic Review; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Publication (AHRQ): Rockville MD, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammad, A.; Thakur, P.; Kumar, R.; Kaur, S.; Saini, R.V.; Saini, A.K. Biological Markers for the Effects of Yoga as a Complementary and Alternative Medicine. J. Complement. Integr. Med. 2019, 16, 20180094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmalzl, L.; Powers, C.; Henje Blom, E. Neurophysiological and Neurocognitive Mechanisms Underlying the Effects of Yoga-Based Practices: Towards a Comprehensive Theoretical Framework. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streeter, C.C.; Whitfield, T.H.; Owen, L.; Rein, T.; Karri, S.K.; Yakhkind, A.; Perlmutter, R.; Prescot, A.; Renshaw, P.F.; Ciraulo, D.A.; et al. Effects of Yoga versus Walking on Mood, Anxiety, and Brain GABA Levels: A Randomized Controlled MRS Study. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2010, 16, 1145–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streeter, C.C.; Jensen, J.E.; Perlmutter, R.M.; Cabral, H.J.; Tian, H.; Terhune, D.B.; Ciraulo, D.A.; Renshaw, P.F. Yoga Asana Sessions Increase Brain GABA Levels: A Pilot Study. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2007, 13, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuppusamy, M.; Kamaldeen, D.; Pitani, R.; Amaldas, J.; Ramasamy, P.; Shanmugam, P.; Vijayakumar, V. Effects of Yoga Breathing Practice on Heart Rate Variability in Healthy Adolescents: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Integr. Med. Res. 2020, 9, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, S.; Melo, F.; Fernandes, O.; Parraca, J.A. Impact of Yoga Training on Heart Rate Variability and Pilot Performance: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Sport Sci. Health 2025, 21, 3039–3049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amit, K.; Singh, D.; Kaligal, C.; Mahadevappa, V.; Krishna, D. Changes in Heart Rate Variability and Executive Functions Following Yoga Practice in Type 2 Diabetes Patients: A Pilot Study. Adv. Mind Body Med. 2023, 37, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Balakrishnan, B.; Metri, K.G.; Day, J.; Ganesan, M. Long-Term Effects of Hatha Yoga on Heart Rate Variability In Healthy Practitioners: Potential Benefits For Cardiovascular Risk Reduction. Altern. Ther. Health Med. 2023, 29, 97–101. [Google Scholar]

- Gomutbutra, P.; Yingchankul, N.; Chattipakorn, N.; Chattipakorn, S.; Srisurapanont, M. The Effect of Mindfulness-Based Intervention on Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF): A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Controlled Trials. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirthalli, J.; Naveen, G.; Rao, M.; Varambally, S.; Christopher, R.; Gangadhar, B. Cortisol and Antidepressant Effects of Yoga. Indian J. Psychiatry 2013, 55, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, H.; Anheyer, D.; Lauche, R.; Dobos, G. A Systematic Review of Yoga for Major Depressive Disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 213, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James-Palmer, A.; Anderson, E.Z.; Zucker, L.; Kofman, Y.; Daneault, J.-F. Yoga as an Intervention for the Reduction of Symptoms of Anxiety and Depression in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Front. Pediatr. 2020, 8, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Cao, D.; Lyu, T.; Gao, W. Meta-Analysis of a Mindfulness Yoga Exercise Intervention on Depression—Based on Intervention Studies in China. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1283172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moosburner, A.; Cramer, H.; Bilc, M.; Triana, J.; Anheyer, D. Yoga for Depressive Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Depress. Anxiety 2024, 2024, 6071055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.G.; Khode, V.; Christa, E.; Desai, R.M.; Chandrasekaran, A.M.; Vadiraja, H.S.; Raghavendra, R.; Aithal, K.; Champa, R.; Deepak, K.K.; et al. Effect of Yoga on Endothelial Function: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Integr. Complement. Med. 2024, 30, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrows, J.L.; Fleury, J. Systematic Review of Yoga Interventions to Promote Cardiovascular Health in Older Adults. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2016, 38, 753–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, T.; Sharma, M.; Branscum, P. Yoga as an Alternative and Complimentary Therapy for Cardiovascular Disease. J. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 22, 310–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghai, S.; Ghai, I. Yoga Nidra for Cardiovascular Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of between- and within-Group Effects. Complement. Ther. Med. 2025, 93, 103231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondolfi, C.; Taffe, P.; Augsburger, A.; Jaques, C.; Malebranche, M.; Clair, C.; Bodenmann, P. Impact of Incarceration on Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Regression on Weight and BMI Change. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e039278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.A.; Redmond, N.; Dennison Himmelfarb, C.R.; Pettit, B.; Stern, M.; Chen, J.; Shero, S.; Iturriaga, E.; Sorlie, P.; Diez Roux, A.V. Cardiovascular Disease in Incarcerated Populations. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017, 69, 2967–2976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimiklis, A.L.; Dahl, V.; Spears, A.P.; Goss, K.; Fogarty, K.; Chacko, A. Yoga, Mindfulness, and Meditation Interventions for Youth with ADHD: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2018, 27, 3155–3168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baggio, S.; Fructuoso, A.; Guimaraes, M.; Fois, E.; Golay, D.; Heller, P.; Perroud, N.; Aubry, C.; Young, S.; Delessert, D.; et al. Prevalence of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Detention Settings: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fazel, S.; Favril, L. Prevalence of Attention-deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Adult Prisoners: An Updated Meta-analysis. Crim. Behav. Ment. Health 2024, 34, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walia, N.; Matas, J.; Turner, A.; Gonzalez, S.; Zoorob, R. Yoga for Substance Use: A Systematic Review. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2021, 34, 964–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanna, S.; Greeson, J.M. A Narrative Review of Yoga and Mindfulness as Complementary Therapies for Addiction. Complement. Ther. Med. 2013, 21, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kissen, M.; Kissen-Kohn, D.A. Reducing Addictions via the Self-Soothing Effects of Yoga. Bull. Menn. Clin. 2009, 73, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posadzki, P.; Choi, J.; Lee, M.S.; Ernst, E. Yoga for Addictions: A Systematic Review of Randomised Clinical Trials. Focus Altern. Complement. Ther. 2014, 19, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N. Neurobiological Basis for the Application of Yoga in Drug Addiction. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1373866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahayu, N.I.; Amalia, T.P.; Damayanti, I. Effect of Yoga Physical Activity on Increasing Self-Control and Quality of Life. J. Kesehat. Masy. 2020, 15, 399–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, A.; Santoshi, V. Stretching Beyond the Self: How Yoga/Mindfulness Cultivates Prosocial Responses to Crisis. Int. J. Indian Psychȯl. 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gard, T.; Noggle, J.J.; Park, C.L.; Vago, D.R.; Wilson, A. Potential Self-Regulatory Mechanisms of Yoga for Psychological Health. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerekes, N.; Fielding, C.; Apelqvist, S. Yoga in Correctional Settings: A Randomized Controlled Study. Front. Psychiatry 2017, 8, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sfendla, A.; Malmström, P.; Torstensson, S.; Kerekes, N. Yoga Practice Reduces the Psychological Distress Levels of Prison Inmates. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auty, K.M.; Cope, A.; Liebling, A. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Yoga and Mindfulness Meditation in Prison. Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. Criminol. 2017, 61, 689–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimberly, A.S. How Yoga Impacts the Substance Use of People Living with HIV Who Are in Reentry from Prison or Jail: A Qualitative Study. Complement. Ther. Med. 2019, 47, 102074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimberly, A.S.; Engstrom, M.; Layde, M.; McKay, J.R. A Randomized Trial of Yoga for Stress and Substance Use among People Living with HIV in Reentry. J. Subst. Abus. Treat. 2018, 94, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derlic, D. A Systematic Review of Literature: Alternative Offender Rehabilitation—Prison Yoga, Mindfulness, and Meditation. J. Correct. Health Care 2020, 26, 361–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishaq, J.; Eyman, K.; Goncy, E.; Williams, L.; Kelton, K.; Knickerbocker, N. A Pilot Study of Yoga with Incarcerated Youth Using the Prison Yoga Project Approach. Int. J. Yoga Ther. 2023, 33, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerekes, N. Yoga as Complementary Care for Young People Placed in Juvenile Institutions—A Study Plan. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 575147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochsner, K.N.; Ray, R.R.; Hughes, B.; McRae, K.; Cooper, J.C.; Weber, J.; Gabrieli, J.D.E.; Gross, J.J. Bottom-Up and Top-Down Processes in Emotion Generation. Psychol. Sci. 2009, 20, 1322–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabbe, L.; Miller-Karas, E. The Trauma Resiliency Model: A “Bottom-Up” Intervention for Trauma Psychotherapy. J. Am. Psychiatr. Nurses Assoc. 2018, 24, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, L.F. The Theory of Constructed Emotion: An Active Inference Account of Interoception and Categorization. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2016, 12, nsw154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrett, L.F.; Atzil, S.; Bliss-Moreau, E.; Chanes, L.; Gendron, M.; Hoemann, K.; Katsumi, Y.; Kleckner, I.R.; Lindquist, K.A.; Quigley, K.S.; et al. The Theory of Constructed Emotion: More Than a Feeling. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2025, 20, 392–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prathikanti, S.; Rivera, R.; Cochran, A.; Tungol, J.G.; Fayazmanesh, N.; Weinmann, E. Treating Major Depression with Yoga: A Prospective, Randomized, Controlled Pilot Trial. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0173869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harkess, K.N.; Delfabbro, P.; Cohen-Woods, S. The Longitudinal Mental Health Benefits of a Yoga Intervention in Women Experiencing Chronic Stress: A Clinical Trial. Cogent Psychol. 2016, 3, 1256037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, K.; Osadchuk, A.; Katz, J. An Eight-Week Yoga Intervention Is Associated with Improvements in Pain, Psychological Functioning and Mindfulness, and Changes in Cortisol Levels in Women with Fibromyalgia. J. Pain Res. 2011, 4, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porges, S.W. The Polyvagal Theory: Neurophysiological Foundations of Emotions, Attachment, Communication, and Self-Regulation, 1st ed.; W. W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-0393707007. [Google Scholar]

- Fazel, S.; Hurton, C.; Burghart, M.; DeLisi, M.; Yu, R. An Updated Evidence Synthesis on the Risk-Need-Responsivity (RNR) Model: Umbrella Review and Commentary. J. Crim. Justice 2024, 92, 102197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, D.A.; Bonta, J.; Wormith, J.S. The Risk-Need-Responsivity (RNR) Model. Crim. Justice Behav. 2011, 38, 735–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilderbeck, A.C.; Farias, M.; Brazil, I.A.; Jakobowitz, S.; Wikholm, C. Participation in a 10-Week Course of Yoga Improves Behavioural Control and Decreases Psychological Distress in a Prison Population. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2013, 47, 1438–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerekes, N.; Brändström, S.; Nilsson, T. Imprisoning Yoga: Yoga Practice May Increase the Character Maturity of Male Prison Inmates. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferdik, F.; Smith, H.P.; Gooch, L.; Boyd, C. Combining Yoga with Expressive Writing to Improve Incarcerated Person Health: A Randomized Waitlist Control Design. Justice Oppor. Rehabil. 2025, 64, 423–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, D.; Long, N.; Jackson, E.; Jurgensen, J. Empowering Through Embodied Awareness: Evaluation of a Peer-Facilitated Trauma-Informed Mindfulness Curriculum in a Woman’s Prison. Prison. J. 2019, 99, 14S–37S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uebelacker, L.A.; Stevens, L.; Graves, H.; Braun, T.D.; Foster, R.; Johnson, J.E.; Tremont, G.; Weinstock, L.M. Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial of a Yoga-Based Intervention Targeting Anger Management for People Who Are Incarcerated. J. Integr. Complement. Med. 2025, 31, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicotera, N.; Viggiano, E. A Pilot Study of a Trauma-Informed Yoga and Mindfulness Intervention With Young Women Incarcerated in the Juvenile Justice System. J. Addict. Offender Couns. 2021, 42, 80–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielly, Y.; Silverthorne, C. Psychological Benefits of Yoga for Female Inmates. Int. J. Yoga Ther. 2017, 27, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovalsky, S.; Hasisi, B.; Haviv, N.; Elisha, E. Can Yoga Overcome Criminality? The Impact of Yoga on Recidivism in Israeli Prisons. Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. Criminol. 2021, 65, 671–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maity, K.; Rain, M.; Dixit, N.; Kumar, S.; Darmora, M.; Verma, P.; Choudhary, S.K.; Gautam, M.; Sharma, K.; Singh, A.; et al. Common Yoga Protocol Modulates Traditional Architecture of Personality and Its Association with the Socio-Demographic Variables of Prisoners: An Exploratory Study. Ann. Neurosci. 2025, 09727531251335421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartels, L.; Oxman, L.N.; Hopkins, A. “I Would Just Feel Really Relaxed and at Peace”: Findings From a Pilot Prison Yoga Program in Australia. Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. Criminol. 2019, 63, 2531–2549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilderbeck, A.C.; Brazil, I.A.; Farias, M. Preliminary Evidence That Yoga Practice Progressively Improves Mood and Decreases Stress in a Sample of UK Prisoners. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2015, 2015, 819183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrett, C. Courting Kids: Inside an Experimental Youth Court; NYU Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-0814709450. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, C.J. Mindfulness and Rehabilitation: Teaching Yoga and Meditation to Young Men in an Alternative to Incarceration Program. Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. Criminol. 2017, 61, 1719–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landau, P.S.; John Gross, J.B. Low Reincarceration Rate Associated with Ananda Marga Yoga and Meditation. Int. J. Yoga Ther. 2008, 18, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncombe, E.; Komorosky, D.; Kim, E.W.; Turner, W. Free Inside. Calif. J. Health Promot. 2005, 3, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rucker, L. Yoga and Restorative Justice in Prison: An Experience of “Response-ability to Harms”. Contemp. Justice Rev. 2005, 8, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambhore, S.; Joshi, P. Effect of Yogic Practices Performed on Deviants Aggression, Anxiety and Impulsiveness in Prison: A Study. J. Psychosoc. Res. 2009, 4, 387–399. [Google Scholar]

- Harner, H.; Hanlon, A.L.; Garfinkel, M. Effect of Iyengar Yoga on Mental Health of Incarcerated Women. Nurs. Res. 2010, 59, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveen, G.H.; Varambally, S.; Thirthalli, J.; Rao, M.; Christopher, R.; Gangadhar, B.N. Serum Cortisol and BDNF in Patients with Major Depression—Effect of Yoga. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2016, 28, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, J.; Otte, C.; Geher, K.; Johnson, J.; Mohr, D.C. Effects of Hatha Yoga and African Dance on Perceived Stress, Affect, and Salivary Cortisol. Ann. Behav. Med. 2004, 28, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunoni, A.R.; Lopes, M.; Fregni, F. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Clinical Studies on Major Depression and BDNF Levels: Implications for the Role of Neuroplasticity in Depression. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008, 11, 1169–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Froeliger, B.E.; Garland, E.L.; Modlin, L.A.; McClernon, F.J. Neurocognitive Correlates of the Effects of Yoga Meditation Practice on Emotion and Cognition: A Pilot Study. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 2012, 6, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaźmierczak, I.; Zajenkowska, A.; Rogoza, R.; Jonason, P.K.; Ścigała, D. Self-Selection Biases in Psychological Studies: Personality and Affective Disorders Are Prevalent among Participants. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0281046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study | Country | Population/Setting | Design | N (Total) | Intervention | Comparator | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bilderbeck et al., 2013 [65] | UK | Adult inmates, 7 prisons | RCT | 100 | 10-week standardized yoga | Wait-list | Mood, stress, cognition |

| Danielly & Silverthorne, 2017 [71] | USA | Female inmates, 2 prisons | Wait-list RCT | 50 | 10-week trauma-informed yoga | Wait-list | Stress, depression, anxiety, self-awareness, self-control |

| Kerekes et al., 2017 (incl. 2018, 2019) [47,48,66] | Sweden | Male and female inmates, 9 prisons | RCT | 152 | 10-week Krimyoga (prison-specific Hatha yoga program) | Physical exercise | Affect, stress, sleep, impulsivity, aggression |

| Bartels et al., 2019 [74] | Australia | Male inmates, high-security prison | Pilot, quantitative + qualitative | 8 | 8-week yoga program | None | Depression, anxiety, stress, self-esteem, affect, emotion regulation |

| Rousseau et al., 2019 [68] | USA | Women’s state prison | Mixed methods | 12 | 8-week trauma-informed yoga (TIMbo) and psychoeducation | None | PTSD, depression, anxiety, self-compassion |

| Kovalsky et al., 2021 [72] | Israel | National prison cohort (matched) | Retrospective, quasi-experimental | 1182 | Weekly yoga classes | Matched non-yoga group | Recidivism (rearrest, reincarceration) |

| Nicotera et al., 2021 [70] | USA | Young women in a juvenile facility | Pilot, Pre–post | 52 | 8-week trauma-informed yoga | None | Mindful awareness/attention (self-regulation) |

| Maity et al., 2025 [73] | India | Adult inmates, model jail | RCT (exploratory) | 191 | 8-week common yoga protocol | Usual routine | Personality traits (S/R/T) |

| Ferdik et al., 2025 [67] | USA | Adult male inmates, medium-security prison | Wait-list RCT | 28 | 8-week combined yoga + expressive writing | Wait-list | Depression, resilience, emotional regulation |

| Uebelacker et al., 2025 [69] | USA | Adult inmates, 2 facilities | Pilot RCT | 40 | 10-week Hatha-based yoga targeting anger management | Health education | Anger, aggression, depression, anxiety, infractions |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Georgiadis, K.; Tzigkounakis, G.; Simati, K.; Tasios, K.; Michopoulos, I.; Giannakidis, V.; Douzenis, A. The Contribution of Yoga to the Psychosocial Rehabilitation and Social Reintegration of Incarcerated Individuals: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2026, 14, 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010070

Georgiadis K, Tzigkounakis G, Simati K, Tasios K, Michopoulos I, Giannakidis V, Douzenis A. The Contribution of Yoga to the Psychosocial Rehabilitation and Social Reintegration of Incarcerated Individuals: A Systematic Review. Healthcare. 2026; 14(1):70. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010070

Chicago/Turabian StyleGeorgiadis, Konstantinos, Giorgos Tzigkounakis, Katerina Simati, Konstantinos Tasios, Ioannis Michopoulos, Vasileios Giannakidis, and Athanasios Douzenis. 2026. "The Contribution of Yoga to the Psychosocial Rehabilitation and Social Reintegration of Incarcerated Individuals: A Systematic Review" Healthcare 14, no. 1: 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010070

APA StyleGeorgiadis, K., Tzigkounakis, G., Simati, K., Tasios, K., Michopoulos, I., Giannakidis, V., & Douzenis, A. (2026). The Contribution of Yoga to the Psychosocial Rehabilitation and Social Reintegration of Incarcerated Individuals: A Systematic Review. Healthcare, 14(1), 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010070