Psychosocial Predictors of Anxiety and Depression in Community-Dwelling Older Adults During a Prolonged Infectious Disease Crisis

Highlights

- Infectious-disease-related stress among older adults is multidimensional, and difficulties in social distancing—rather than fear of infection—were the most influential predictor of anxiety and depression.

- Emotional support was the strongest protective factor for both anxiety and depression, while material support provided extra protection specifically for depression.

- Mental health interventions should focus on maintaining social connectedness and reducing distancing-related strain, rather than emphasizing infection fear alone.

- Community-based emotional support systems and reliable resource delivery networks should be integrated into routine public health preparedness to sustain older adults’ well-being during prolonged crises.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Instruments

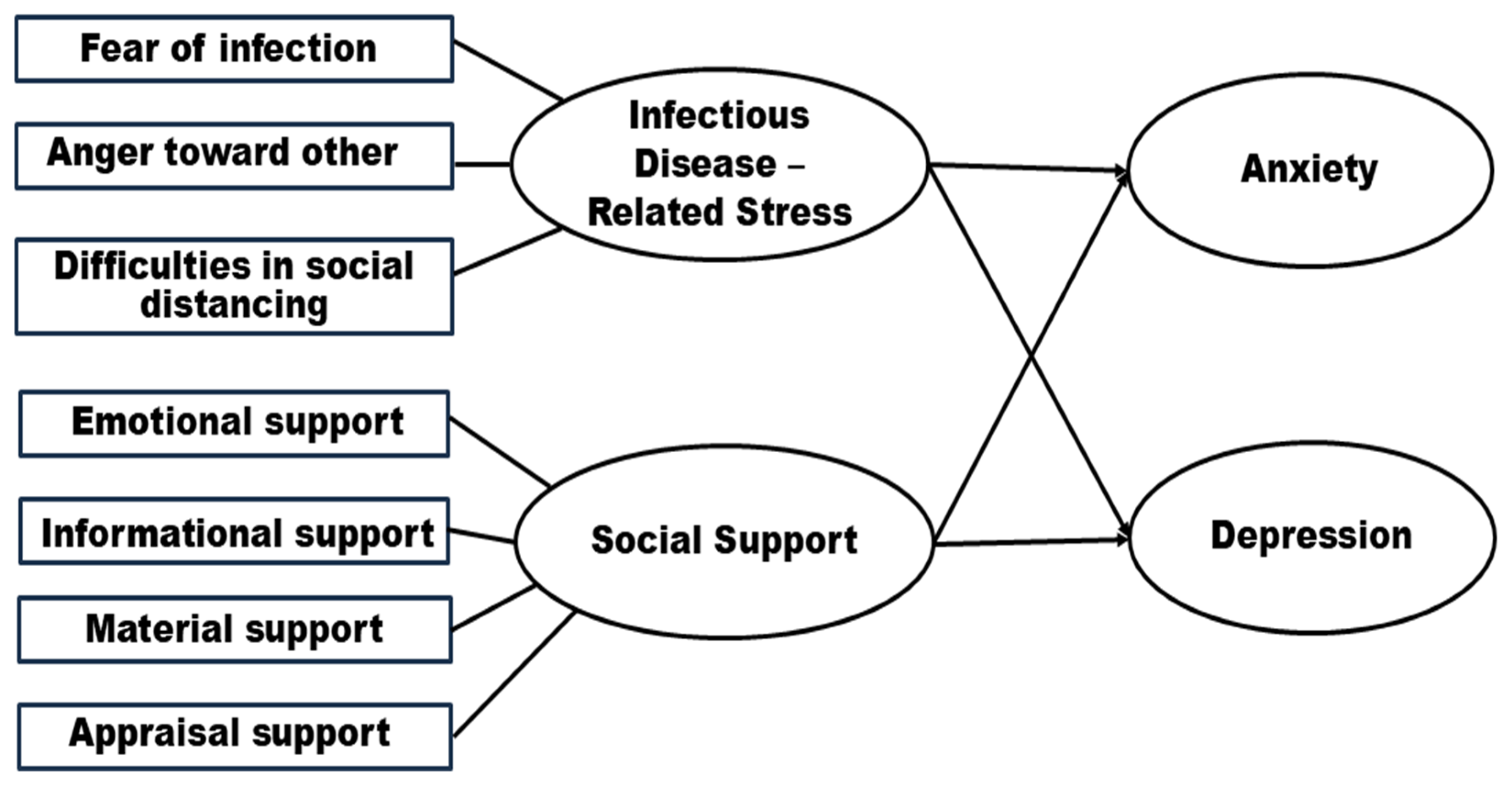

2.3.1. Infectious Disease-Related Stress

2.3.2. Social Support

2.3.3. Anxiety

2.3.4. Depression

2.4. Data Collection and Ethical Considerations

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics and Group Differences in Anxiety and Depression

3.2. Levels of Anxiety, Depression, Infectious Disease-Related Stress, and Social Support

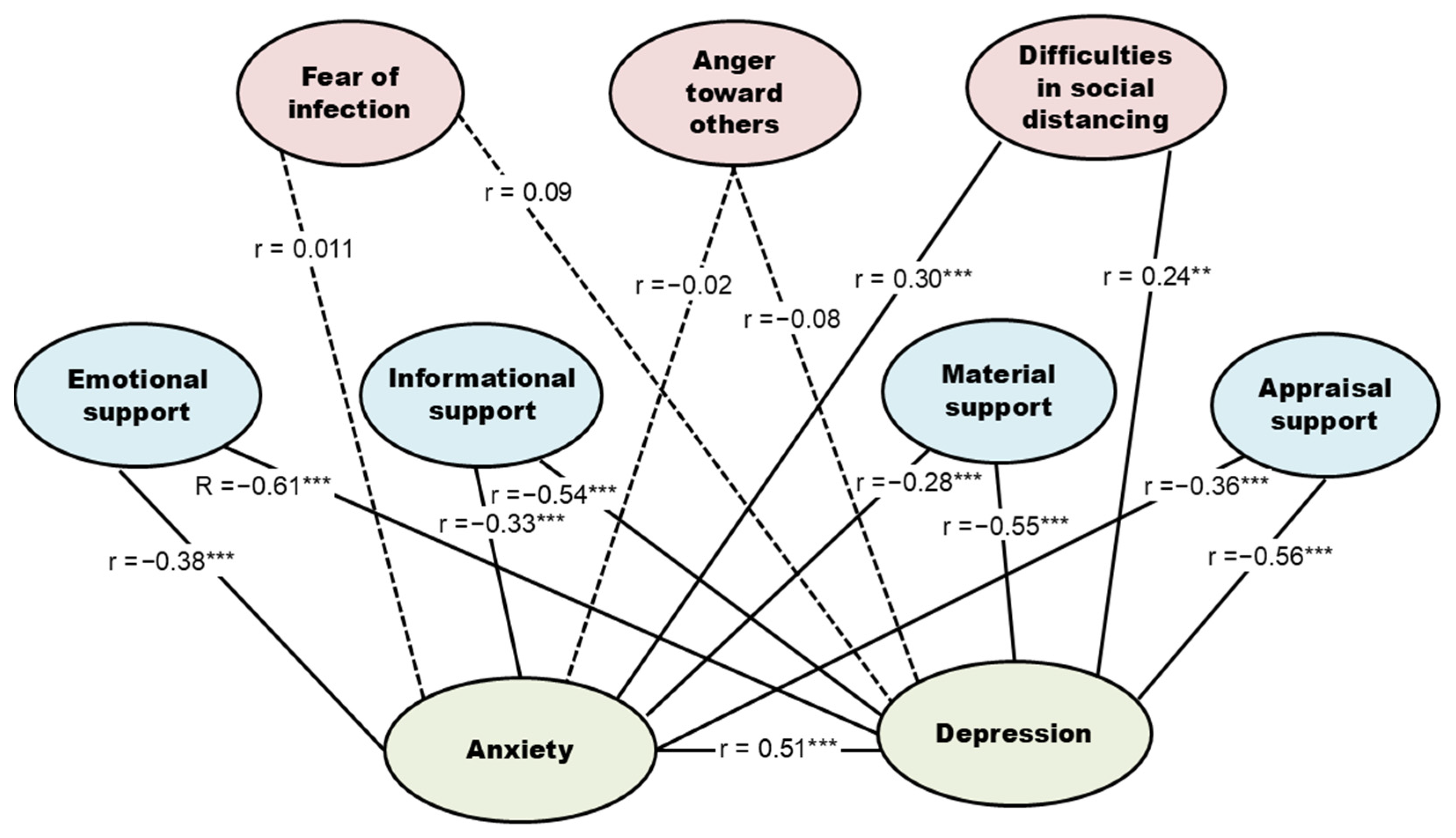

3.3. Correlations Among Anxiety, Depression, Infectious Disease-Related Stress, and Social Support

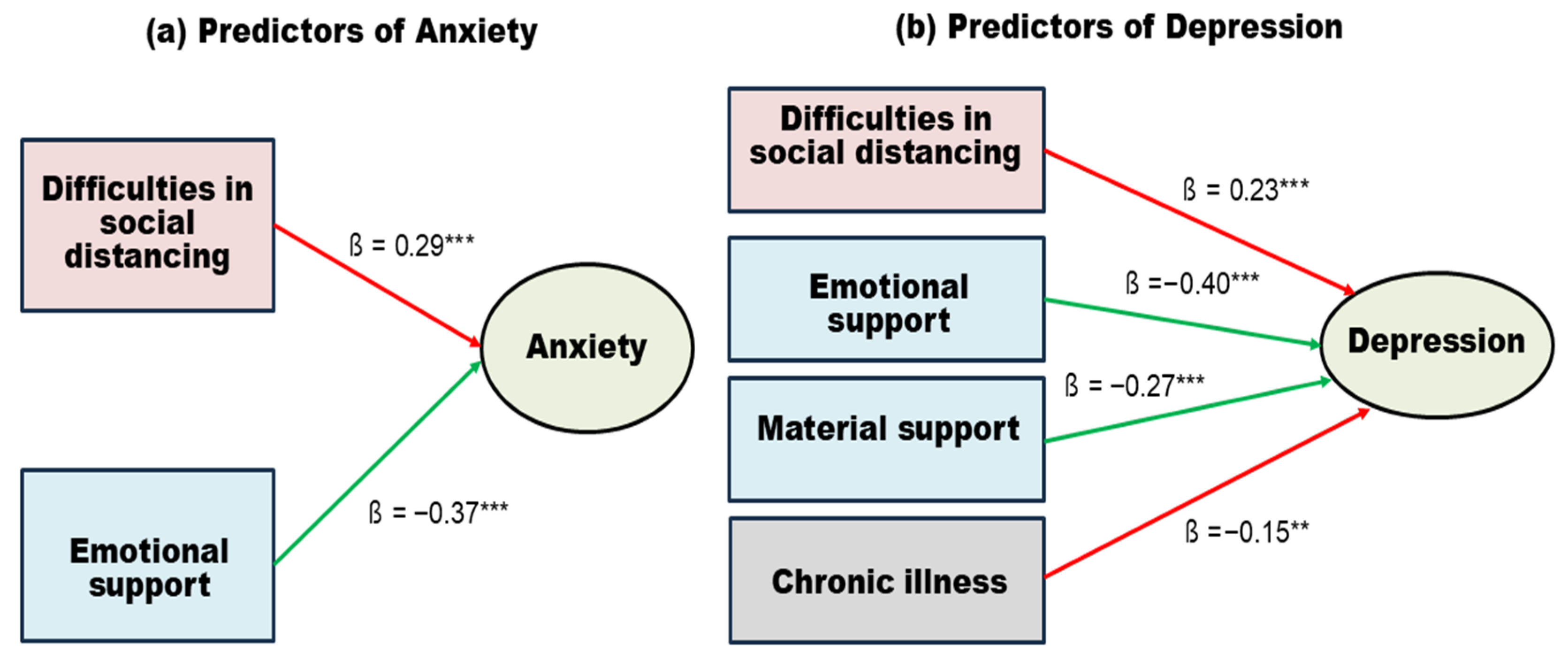

3.4. Predictors of Anxiety and Depression in Community-Dwelling Older Adults

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| EMA | Ecological Momentary Assessment |

| JITAI | Just-in-Time Adaptive Intervention |

| K-CSS | Korean COVID-19 Stress Scale |

| K-GAI | Korean Geriatric Anxiety Inventory |

| K-GDS-SF | Korean Geriatric Depression Scale—Short Form |

| K-MSPSS | Korean version of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support |

| MERS | Middle East Respiratory Syndrome |

| SARS | Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome |

References

- Cénat, J.M.; Blais-Rochette, C.; Kokou-Kpolou, C.K.; Noorishad, P.G.; Mukunzi, J.N.; McIntee, S.E.; Dalexis, R.D.; Goulet, M.A.; Labelle, P.R. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, PTSD and psychological distress among populations affected by the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 291, 113599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Comprehensive Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2030; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240031029 (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Armitage, R.; Nellums, L.B. COVID-19 and the consequences of isolating the elderly. Lancet Public Health 2020, 5, e256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vahia, I.V.; Jeste, D.V.; Reynolds, C.F. Older adults and the mental health effects of COVID-19. JAMA 2020, 324, 2253–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepúlveda-Loyola, W.; Rodríguez-Sánchez, I.; Pérez-Rodríguez, P.; Ganz, F.; Torralba, R.; Oliveira, D.V.; Rodríguez-Mañas, L. Impact of social isolation due to COVID-19 on health in older people: Mental and physical effects and recommendations. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2020, 24, 938–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orlandini, R.; Matana, A.; Švaljug, D.; Gusar, I.; Antičević, V. Predictors of Loneliness and Psychological Distress in Older Adults During the COVID-19 Pandemic: National Cross-Sectional Study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2025, 11, e78728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerbara, L.; Ciancimino, G.; Crescimbene, M.; La Longa, F.; Parsi, M.R.; Tintori, A.; Palomba, R. Nationwide survey on emotional and psychological impact of COVID-19 social distancing. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2020, 24, 7155–7163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenze, E.J.; Wetherell, J.L. Anxiety disorders: New developments in old age. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2011, 19, 301–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 2020, 395, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matud, M.P. COVID-19 and mental distress and well-being among older people: A gender analysis in the first and last year of the pandemic and in the post-pandemic period. Geriatrics 2025, 10, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, E.G.; Pilitye, R. Older adults’ mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2022, 37, e266–e277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, O.; Sousa, L.; Sampaio, F.; Rodrigues, C.; Santos, N.C.; Sequeira, C.; Teixeira, L. Loneliness and Mental Health Disorders in Older Adults Living in Portugal During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Pan, K.; Li, J.; Jiang, M.; Gao, Y.; Yang, H. The associations of social isolation with depression and anxiety among adults aged 65 years and older in Ningbo, China. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 19072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groarke, J.M.; Berry, E.; Graham-Wisener, L.; McKenna-Plumley, P.E.; McGlinchey, E.; Armour, C. Loneliness in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic: Cross-sectional results from the COVID-19 psychological wellbeing study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0239698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, D.; Rai, M. Social isolation in COVID-19: The impact of loneliness. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2020, 66, 525–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santini, Z.I.; Jose, P.E.; York Cornwell, E.; Koyanagi, A.; Nielsen, L.; Hinrichsen, C.; Meilstrup, C.; Madsen, K.R.; Koushede, V. Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and symptoms of depression and anxiety among older Americans (NSHAP): A longitudinal mediation analysis. Lancet Public Health 2020, 5, e62–e70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuller, H.R.; Huseth-Zosel, A. Lessons in resilience: Initial coping among older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Gerontologist 2021, 61, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Dong, S.; Yu, Z.; Bi, S.; Wen, W.; Li, J. Internet usage, social participation, and depression symptoms among middle-aged and older adults before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e67039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Killgore, W.D.S.; Cloonan, S.A.; Taylor, E.C.; Lucas, D.A.; Dailey, N.S. Loneliness during the first half-year of COVID-19 lockdowns. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 291, 113237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killgore, W.D.S.; Cloonan, S.A.; Taylor, E.C.; Miller, M.A.; Dailey, N.S. Three months of loneliness during the COVID-19 lockdown. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 293, 113392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazer, D.G.; Hybels, C.F. Origins of depression in later life. Psychol. Med. 2005, 35, 1241–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiske, A.; Wetherell, J.L.; Gatz, M. Depression in older adults. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2009, 5, 363–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, K.; Stanley, M.A. Anxiety disorders in late life. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2020, 36, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bei, B.; Bryant, C.; Gilson, K.M.; Koh, J. A prospective study of the impact of floods on the mental and physical health of older adults. Aging Ment. Health 2013, 17, 992–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadirappulli-Hewage, M.; Jayasekara, R. Social connectedness in preventing suicide among older adults. OBM Geriatrics 2020, 4, 096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Mental Health of Older Adults: Fact Sheet; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland , 2023; Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-of-older-adults (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Jeong, K.-H.; Ryu, J.H.; Lee, S.; Kim, S. Changes in depression trends during and after the COVID-19 pandemic among older adults in Korea. Glob. Ment. Health 2024, 11, e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Wills, T.A. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 1985, 98, 310–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wethington, E.; Kessler, R.C. Perceived support, received support, and adjustment to stressful life events. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1986, 27, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holt-Lunstad, J.; Smith, T.B.; Baker, M.; Harris, T.; Stephenson, D. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 10, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, S.; Landry, C.A.; Paluszek, M.M.; Fergus, T.A.; McKay, D.; Asmundson, G.J.G. Development and initial validation of the COVID Stress Scales. J. Anxiety Disord. 2020, 72, 102232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Park, H.; Park, S.; Lee, Y. Development and Initial Validation of the COVID Stress Scale for Korean People. Korea J. Couns. 2021, 22, 141–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J. A Study for the Development of a Social Support Scale. Ph.D. Thesis, Yonsei University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K. Validation of the Social Support Scale for the Middle and the Elderly: An Application of Item Response Theory. Soc. Welf. Res. 2021, 52, 219–249. [Google Scholar]

- Pachana, N.A.; Byrne, G.J.; Siddle, H.; Koloski, N.; Harley, E.; Arnold, E. Development and validation of the Geriatric Anxiety Inventory. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2007, 19, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Park, M.S.; Oh, D.N. Reliability and validity of the Korean version of the Geriatric Anxiety Inventory (K-GAI). J. Muscle Jt. Health 2014, 21, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, J.I.; Yesavage, J.A. Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS): Development of a shorter version. Clin. Gerontol. 1986, 5, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gi, B.S.; Lee, C.W. A Preliminary Study for the Standardization of the Korean Geriatric Depression Scale. J. Korean Neuropsychiatr. Assoc. 1995, 34, 1875–1885. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.Y. Statistical notes for clinical researchers: Assessing normal distribution (2) using skewness and kurtosis. Restor. Dent. Endod. 2013, 38, 52–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreas, S.; Schulz, H.; Volkert, J.; Dehoust, M.; Sehner, S.; Suling, A.; Ausín, B.; Canuto, A.; Crawford, M.; Da Ronch, C.; et al. Prevalence of mental disorders in elderly people: The European MentDis_ICF65+ study. Br. J. Psychiatry 2017, 210, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larnyo, E.; Ebenezer, L.; Brianna, G.; Jonathan, A.N.; Natasha, P.; Stephen, A.D.; Natalia, D.; Senyuan, L. Effect of social capital, social support, and social network formation on quality of life during COVID-19. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 2647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Xiao, Y.; Xu, P.; Dong, S. Social support and mental health symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic: A comprehensive meta-analysis unveils limited protective effects. J. Pac. Rim Psychol. 2025, 19, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, H.; Xu, Y.; Dai, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, B.; Yang, H. Analyze the psychological impact of COVID-19 among the elderly population in China and make corresponding suggestions. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 289, 112983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lee, J.-E.; Kim, S.; Min, H.S.; Lee, K.-S. Social network, perceived neighborhood satisfaction, and depressive symptoms among older adults in Korea. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 42319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.; Benoit, E.; Windsor, L. Effects of social support and self-efficacy on hopefulness in low-income older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Geriatr. 2024, 24, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Xiong, J.; Tang, S.; Bishwajit, G.; Guo, S. Social support and psychosocial well-being among older adults in Europe during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e071533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifert, A.; Cotten, S.R.; Xie, B. A double burden of exclusion? Digital and social exclusion of older adults in times of COVID-19. J. Gerontol. Soc. Sci. 2021, 76, e99–e103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyun, J.; You, S.; Sohn, S.; Kim, S.J.; Bae, J.; Baik, S.Y. Psychosocial support during the COVID-19 outbreak in Korea. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2020, 35, e211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations. Decade of Healthy Ageing 2021–2030; UN: New York, NY, USA, 2020; Available online: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3895802?ln=en (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- World Health Organization. Integrated Care for Older People (ICOPE): Guidance for Person-Centred Assessment and Pathways in Primary Care; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/b/71300 (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Wu, M.; Li, C.; Hu, T.; Zhao, X.; Qiao, G.; Gao, X.; Zhu, X.; Yang, F. Effectiveness of telecare interventions on depression and anxiety among older adults. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2024, 12, e50787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations. Policy Brief: COVID-19 and the Need for Action on Mental Health; UN: New York, NY, USA, 2020; Available online: https://unsdg.un.org/sites/default/files/2020-05/UN-Policy-Brief-COVID-19-and-mental-health.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2025).

| Variables | Categories | n (%) | Anxiety | Depression | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | t or F (p) | η2 | Mean ± SD | t or F (p) | η2 | |||

| Sex | Male | 76 (42.7) | 5.89 ± 6.76 | 0.04 (0.965) | 5.75 ± 4.70 | −0.61 (0.540) | ||

| Female | 102 (57.3) | 5.85 ± 5.56 | 6.17 ± 4.31 | |||||

| Age | 65~69 | 86 (48.3) | 5.57 ± 5.70 | 0.31 (0.737) | 5.55 ± 4.44 | 0.82 (0.441) | ||

| 70~79 | 69 (38.8) | 5.99 ± 6.72 | 6.36 ± 4.69 | |||||

| ≥80~ | 23 (12.9) | 6.65 ± 5.56 | 6.52 ± 3.92 | |||||

| Marital Status | Widow/Widower | 42 (23.6) | 7.21 ± 6.23 | 3.25 (0.156) | 7.29 ± 4.50 | 2.53 (0.082) | ||

| Married | 125 (70.2) | 5.16 ± 5.82 | 5.52 ± 4.38 | |||||

| Unmarried | 11 (6.2) | 8.82 ± 7.14 | 6.36 ± 4.90 | |||||

| Living situations | Alone | 39 (21.9) | 5.70 ± 5.98 | −0.72 (0.475) | 5.87 ± 4.33 | −0.67 (0.507) | ||

| Lives with another | 139 (78.1) | 6.49 ± 6.48 | 6.41 ± 4.98 | |||||

| Religion | Yes | 121 (68.0) | 5.81 ± 5.97 | −0.19 (0.846) | 5.52 ± 4.54 | −2.05 (0.042) | ||

| No | 57 (32.0) | 6.00 ± 6.36 | 6.98 ± 4.19 | |||||

| Education level | ≤Middle a | 72 (40.5) | 7.88 ± 6.54 | 6.95 (0.001) a > b,c † | 0.07 | 7.51 ± 4.34 | 8.60 (<0.001) a > b,c † | 0.09 |

| High b | 57 (32.0) | 4.86 ± 5.65 | 5.49 ± 4.58 | |||||

| ≥College c | 49 (27.5) | 4.10 ± 5.05 | 4.33 ± 3.87 | |||||

| Medical Insurance type | National basic living security | 30 (16.9) | 9.93 ± 6.90 | 3.64 (0.001) | 9.33 ± 4.09 | 4.76 (<0.001) | ||

| General Health insurance | 148 (83.1) | 5.05 ± 5.57 | 5.31 ± 4.25 | |||||

| Perceived health status | Bad a | 41 (23.0) | 8.51 ± 6.13 | 6.02 (0.003) a > b,c † | 0.06 | 9.44 ± 3.69 | 33.14 (<0.001) a > b > c † | 0.28 |

| Moderate b | 74 (41.6) | 5.64 ± 6.01 | 6.04 ± 4.56 | |||||

| Good c | 63 (35.4) | 4.43 ± 5.66 | 3.68 ± 3.26 | |||||

| Disease | Yes | 134 (75.3) | 5.96 ± 6.07 | 0.35 (0.726) | 6.37 ± 4.58 | 2.02 (0.045) | ||

| No | 44 (24.7) | 5.59 ± 6.18 | 4.82 ± 3.94 | |||||

| Activity place | Yes | 141 (79.2) | 6.19 ± 6.22 | 1.38 (0.170) | 6.05 ± 4.65 | 0.40 (0.693) | ||

| No | 37 (20.8) | 4.65 ± 5.44 | 5.76 ± 3.80 | |||||

| Number of supportive members | 0~2 a | 51 (28.7) | 7.71 ± 6.06 | 3.40 (0.060) | 8.37 ± 4.12 | 12.81 (<0.001) a > b,c † | 0.13 | |

| 3~4 b | 58 (32.6) | 4.95 ± 5.92 | 5.69 ± 4.39 | |||||

| ≥5 c | 69 (38.7) | 5.29 ± 6.02 | 4.48 ± 4.11 | |||||

| COVID-19 experience | Yes | 7 (3.9) | 5.71 ± 6.50 | −0.07 (0.945) | 7.14 ± 5.52 | 0.70 (0.488) | ||

| No | 171 (96.1) | 5.88 ± 6.08 | 5.94 ± 4.44 | |||||

| Vaccination | Yes | 174 (97.8) | 5.88 ± 6.12 | 0.12 (0.902) | 5.90 ± 4.47 | −1.83 (0.070) | ||

| No | 4 (2.2) | 5.50 ± 4.43 | 10.00 ± 2.16 | |||||

| Variables | Mean | SD | Min | Max | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infectious Disease-Related Stress | 57.40 | 12.11 | 5 | 84 | −0.79 | 1.57 |

| Fear of infection | 24.28 | 6.74 | 3 | 36 | −0.78 | 0.58 |

| Anger toward others | 18.69 | 4.15 | 0 | 24 | −1.16 | 2.47 |

| Difficulties in social distancing | 14.43 | 4.70 | 1 | 24 | −0.40 | 0.00 |

| Social Support | 58.99 | 15.41 | 17 | 85 | −0.47 | −0.01 |

| Emotional support | 28.46 | 7.59 | 8 | 40 | −0.59 | 0.06 |

| Informational support | 10.29 | 2.98 | 3 | 15 | −0.46 | −0.16 |

| Material support | 9.74 | 3.35 | 3 | 15 | −0.12 | −0.90 |

| Appraisal support | 10.51 | 3.04 | 3 | 15 | −0.37 | −0.37 |

| Anxiety | 5.87 | 6.08 | 0 | 20 | 0.81 | −0.63 |

| Depression | 5.99 | 4.47 | 0 | 15 | 0.36 | −1.13 |

| Variables | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r(p) | |||||||||

| 1.1. Fear of infection | 1 | ||||||||

| 1.2. Anger toward others | 0.46 (<0.001) | 1 | |||||||

| 1.3. Difficulties in social distancing | 0.39 (<0.001) | 0.29 (<0.001) | 1 | ||||||

| 2.1. Emotional support | −0.02 (0.787) | 0.25 (0.001) | −0.03 (0.654) | 1 | |||||

| 2.2. Informational support | 0.01 (0.922) | 0.26 (<0.001) | 0.03 (0.670) | 0.81 (<0.001) | 1 | ||||

| 2.3. Material support | 0.02 (0.777) | 0.22 (0.003) | −0.04 (0.581) | 0.68 (<0.001) | 0.70 (<0.001) | 1 | |||

| 2.4. Appraisal support | 0.06 (0.429) | 0.23 (0.002) | −0.07 (0.346) | 0.76 (<0.001) | 0.78 (<0.001) | 0.81 (<0.001) | 1 | ||

| 3. Anxiety | 0.11 (0.165) | −0.02 (0.764) | 0.30 (<0.001) | −0.38 (<0.001) | −0.33 (<0.001) | −0.28 (<0.001) | −0.36 (<0.001) | 1 | |

| 4. Depression | 0.09 (0.227) | −0.08 (0.278) | 0.24 (0.002) | −0.61 (<0.001) | −0.54 (<0.001) | −0.55 (<0.001) | −0.56 (<0.001) | 0.51 (<0.001) | 1 |

| Independent Variables | Dependent Variables | B | S.E. | β | t(p) | R2 | Adjusted R2 | F(p) | Durbin- Watson |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional support * | −0.29 | 0.05 | −0.37 | −5.48 (<0.001) | 0.22 | 0.22 | 25.33 (<0.001) | 2.01 | |

| Difficulties in social distancing * | Anxiety | 0.38 | 0.09 | 0.29 | 4.36 (<0.001) | ||||

| Emotional support ** | −0.24 | 0.05 | −0.40 | −5.32 (<0.001) | 0.47 | 0.46 | 38.18 (<0.001) | 2.10 | |

| Difficulties in social distancing ** | Depression | 0.22 | 0.05 | 0.23 | 4.06 (<0.001) | ||||

| Material support ** | −0.36 | 0.10 | −0.27 | −3.57 (<0.001) | |||||

| Disease (ref: Yes) ** | −1.54 | 0.58 | −0.15 | −2.66 (0.009) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kim, N.H.; Hong, S.H.; Park, H.J.; Shin, S.H. Psychosocial Predictors of Anxiety and Depression in Community-Dwelling Older Adults During a Prolonged Infectious Disease Crisis. Healthcare 2026, 14, 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010048

Kim NH, Hong SH, Park HJ, Shin SH. Psychosocial Predictors of Anxiety and Depression in Community-Dwelling Older Adults During a Prolonged Infectious Disease Crisis. Healthcare. 2026; 14(1):48. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010048

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Nam Hee, Seung Hyun Hong, Hyun Jae Park, and Sung Hee Shin. 2026. "Psychosocial Predictors of Anxiety and Depression in Community-Dwelling Older Adults During a Prolonged Infectious Disease Crisis" Healthcare 14, no. 1: 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010048

APA StyleKim, N. H., Hong, S. H., Park, H. J., & Shin, S. H. (2026). Psychosocial Predictors of Anxiety and Depression in Community-Dwelling Older Adults During a Prolonged Infectious Disease Crisis. Healthcare, 14(1), 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010048