Evaluating Palliative Care Needs in Patients with Advanced Non-Malignant Chronic Conditions: An Umbrella Review of Needs Assessment Tools

Highlights

- This umbrella review identified 35 needs assessment tools for patients with advanced non-malignant chronic conditions, with only a limited number integrating both general and disease-specific palliative care indicators.

- Significant gaps were found in the psychometric evidence of most tools, with NAT: PD-HF, SPICT, and NECPAL emerging as the most promising for this patient population.

- Early identification of palliative care needs should prioritize tools that predict functional decline and incorporate both general and disease-specific indicators to support timely and targeted interventions.

- Further research is required to strengthen the psychometric properties and clinical utility of existing tools and to develop more holistic assessment tools covering physical, psychological, social, and spiritual domains.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Study Selection and Quality Appraisal

2.4. Data Extraction and Synthesis

3. Results

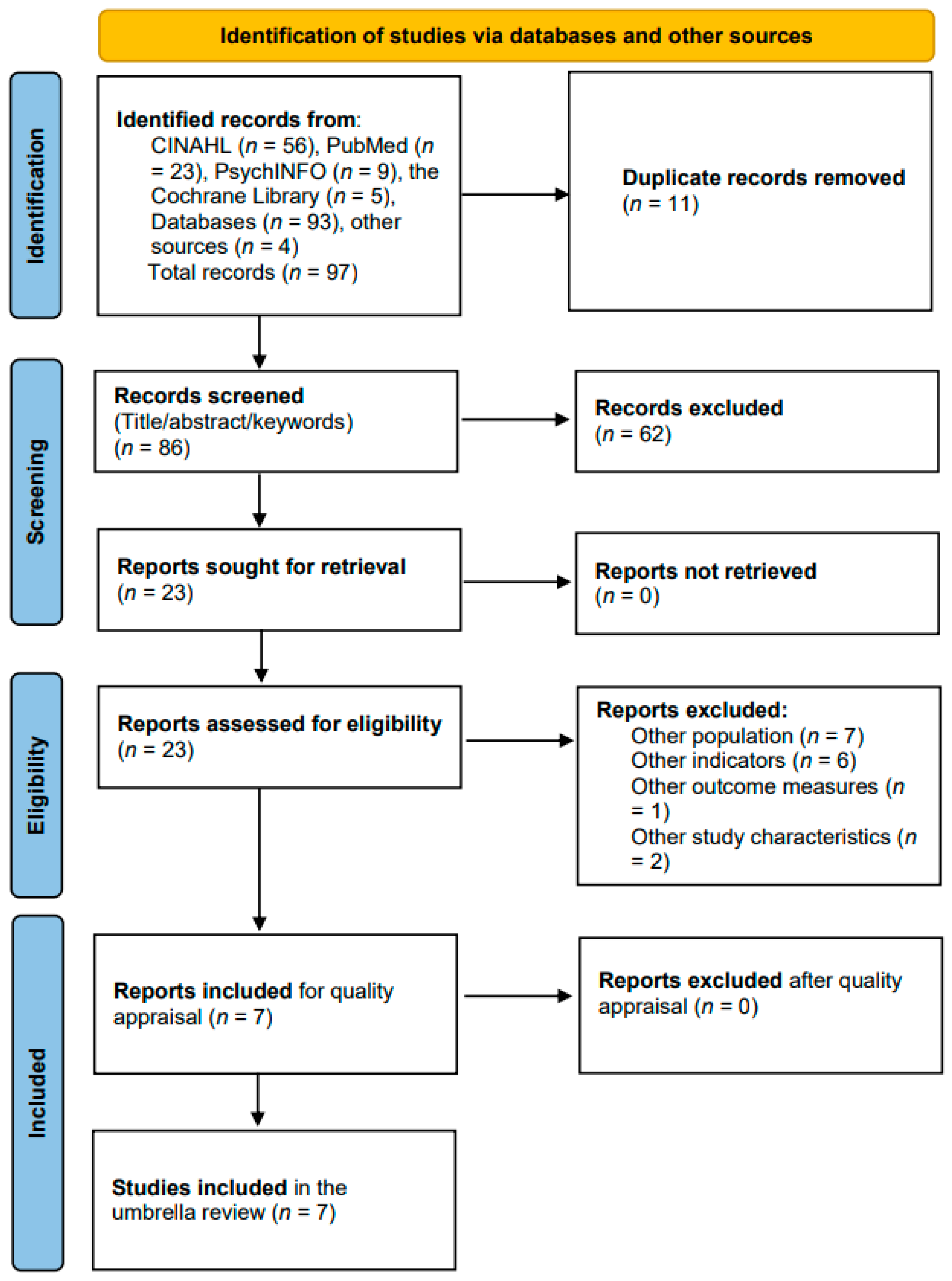

3.1. Selected Studies

3.2. Characteristics of the Included Studies

3.3. Risk of Bias Across Studies

3.4. Characteristics of the Needs Assessment Tools

3.5. Psychometric Properties of the Needs Assessment Tools

3.5.1. Tools with Strongest Validity and/or Reliability

3.5.2. Tools with Inconsistent or Weak Psychometric Findings

3.5.3. Tools Lacking Psychometric Evaluation in the Included Reviews

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Registration

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADL | Activities of Daily Living |

| A-qCPR | Admission Quick Sequential Organ Failure Assessment for the Chronic Palliative Risk |

| ALS | Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis |

| COPD | Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

| COSMIN | COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments |

| CSHA-CFS | Canadian Study of Health and Aging–Clinical Frailty Scale |

| ED | Emergency Department |

| EDs | Emergency Departments |

| eFI | Electronic Frailty Index |

| ESAS | Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale |

| FAST | Functional Assessment Staging Test |

| GSF-PIG | Gold Standards Framework–Proactive Identification Guidance |

| HF | Heart Failure |

| IPOS | Integrated Palliative care Outcome Scale |

| JBI | Joanna Briggs Institute |

| KCCQ | Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire |

| MQOL | McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire |

| NAT: PD-HF | Needs Assessment Tool: Progressive Disease–Heart Failure |

| NECPAL | NECesidades Paliativas |

| PC | Palliative Care |

| PC-NAT | Palliative Care Needs Assessment Tool |

| PPS | Palliative Performance Scale |

| PRIOR | Preferred Reporting Items for Overviews of Reviews |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PROSPERO | International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews |

| QUADAS-2 | Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies 2 |

| RAI | Risk Analysis Index |

| SPEED | Screening for Palliative and End-of-life care needs in the Emergency Department |

| SPICT | Supportive and Palliative Care Indicators Tool |

| SQ | Surprise Question |

| SST | Simplified Screening Tool |

| TW-PCST | Taiwanese version–Palliative Care Screening Tool |

References

- Patel, P.; Lyons, L. Examining the Knowledge, Awareness, and Perceptions of Palliative Care in the General Public Over Time: A Scoping Literature Review. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care 2020, 37, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanuseputro, P.; Wodchis, W.P.; Fowler, R.; Walker, P.; Bai, Y.Q.; Bronskill, S.E.; Manuel, D. The Health Care Cost of Dying: A Population-Based Retrospective Cohort Study of the Last Year of Life in Ontario, Canada. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0121759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, J.J.; Alam, S.; Cahill, L.E.; Drucker, A.M.; Gotay, C.; Kayibanda, J.F.; Kozloff, N.; Mate, K.K.V.; Patten, S.B.; Orpana, H.M. Global Burden of Disease Study Trends for Canada from 1990 to 2016. CMAJ 2018, 190, E1296–E1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavalieratos, D.; Corbelli, J.; Zhang, D.; Dionne-Odom, J.N.; Ernecoff, N.C.; Hanmer, J.; Hoydich, Z.P.; Ikejiani, D.Z.; Klein-Fedyshin, M.; Zimmermann, C.; et al. Association Between Palliative Care and Patient and Caregiver Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA 2016, 316, 2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIlvennan, C.K.; Allen, L.A. Palliative Care in Patients with Heart Failure. BMJ 2016, 353, i1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worldwide Hospice Palliative Care Alliance; World Health Organization. Global Atlas of Palliative Care, 2nd ed.; The Worldwide Hospice Palliative Care Alliance: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lunney, J.R. Patterns of Functional Decline at the End of Life. JAMA 2003, 289, 2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seow, H.; O’Leary, E.; Perez, R.; Tanuseputro, P. Access to Palliative Care by Disease Trajectory: A Population-Based Cohort of Ontario Decedents. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e021147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chidiac, C. The Evidence of Early Specialist Palliative Care on Patient and Caregiver Outcomes. Int. J. Palliat. Nurs. 2018, 24, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knaul, F.M.; Farmer, P.E.; Krakauer, E.L.; De Lima, L.; Bhadelia, A.; Jiang Kwete, X.; Arreola-Ornelas, H.; Gómez-Dantés, O.; Rodriguez, N.M.; Alleyne, G.A.O.; et al. Alleviating the Access Abyss in Palliative Care and Pain Relief—An Imperative of Universal Health Coverage: The Lancet Commission Report. Lancet 2018, 391, 1391–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwete, X.J.; Bhadelia, A.; Arreola-Ornelas, H.; Mendez, O.; Rosa, W.E.; Connor, S.; Downing, J.; Jamison, D.; Watkins, D.; Calderon, R.; et al. Global Assessment of Palliative Care Need: Serious Health-Related Suffering Measurement Methodology. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 2024, 68, e116–e137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moens, K.; Higginson, I.J.; Harding, R.; Brearley, S.; Caraceni, A.; Cohen, J.; Costantini, M.; Deliens, L.; Francke, A.L.; Kaasa, S.; et al. Are There Differences in the Prevalence of Palliative Care-Related Problems in People Living with Advanced Cancer and Eight Non-Cancer Conditions? A Systematic Review. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 2014, 48, 660–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currow, D.C.; Allingham, S.; Bird, S.; Yates, P.; Lewis, J.; Dawber, J.; Eagar, K. Referral Patterns and Proximity to Palliative Care Inpatient Services by Level of Socio-Economic Disadvantage. A National Study Using Spatial Analysis. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2012, 12, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, B.; Calanzani, N.; Curiale, V.; McCrone, P.; Higginson, I.J.; De Brito, M. Effectiveness and Cost-Effectiveness of Home Palliative Care Services for Adults with Advanced Illness and Their Caregivers. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 2022, CD007760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaertner, J.; Siemens, W.; Meerpohl, J.J.; Antes, G.; Meffert, C.; Xander, C.; Stock, S.; Mueller, D.; Schwarzer, G.; Becker, G. Effect of Specialist Palliative Care Services on Quality of Life in Adults with Advanced Incurable Illness in Hospital, Hospice, or Community Settings: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMJ 2017, 357, j2925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, C.; Swami, N.; Krzyzanowska, M.; Hannon, B.; Leighl, N.; Oza, A.; Moore, M.; Rydall, A.; Rodin, G.; Tannock, I.; et al. Early Palliative Care for Patients with Advanced Cancer: A Cluster-Randomised Controlled Trial. Lancet 2014, 383, 1721–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanbutsele, G.; Pardon, K.; Van Belle, S.; Surmont, V.; De Laat, M.; Colman, R.; Eecloo, K.; Cocquyt, V.; Geboes, K.; Deliens, L. Effect of Early and Systematic Integration of Palliative Care in Patients with Advanced Cancer: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018, 19, 394–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bornais, C.; Deravin-Malone, L. Early Palliative Care for Patients with Metastatic Lung Cancer: Evidence for and Barriers Against. Nurs. Palliat. Care 2016, 1, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temel, J.S.; Greer, J.A.; Muzikansky, A.; Gallagher, E.R.; Admane, S.; Jackson, V.A.; Dahlin, C.M.; Blinderman, C.D.; Jacobsen, J.; Pirl, W.F.; et al. Early Palliative Care for Patients with Metastatic Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 733–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allsop, M.J.; Ziegler, L.E.; Mulvey, M.R.; Russell, S.; Taylor, R.; Bennett, M.I. Duration and Determinants of Hospice-Based Specialist Palliative Care: A National Retrospective Cohort Study. Palliat. Med. 2018, 32, 1322–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, D.J.; Boyne, J.; Currow, D.C.; Schols, J.M.; Johnson, M.J.; La Rocca, H.-P.B. Timely Recognition of Palliative Care Needs of Patients with Advanced Chronic Heart Failure: A Pilot Study of a Dutch Translation of the Needs Assessment Tool: Progressive Disease—Heart Failure (NAT:PD-HF). Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2019, 18, 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rego, F.; Nunes, R. The Interface Between Psychology and Spirituality in Palliative Care. J. Health Psychol. 2019, 24, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bausewein, C.; Daveson, B.A.; Currow, D.C.; Downing, J.; Deliens, L.; Radbruch, L.; Defilippi, K.; Lopes Ferreira, P.; Costantini, M.; Harding, R.; et al. EAPC White Paper on Outcome Measurement in Palliative Care: Improving Practice, Attaining Outcomes and Delivering Quality Services—Recommendations from the European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC) Task Force on Outcome Measurement. Palliat. Med. 2016, 30, 6–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, N.; Phillips, E.; Zaurova, M.; Song, C.; Lamba, S.; Grudzen, C. Palliative Care Screening and Assessment in the Emergency Department: A Systematic Review. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 2016, 51, 108–119.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, R.I.; Mitchell, G.; Francis, L.; Van Driel, M.L. What Diagnostic Tools Exist for the Early Identification of Palliative Care Patients in General Practice? A Systematic Review. J. Palliat. Care 2015, 31, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Downar, J.; Wegier, P.; Tanuseputro, P. Early Identification of People Who Would Benefit from a Palliative Approach—Moving From Surprise to Routine. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e1911146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, P.; Greenslade, J.; Shanmugathasan, S.; Doucet, K.; Widdicombe, N.; Chu, K.; Brown, A. PREDICT: A Diagnostic Accuracy Study of a Tool for Predicting Mortality within One Year: Who Should Have an Advance Healthcare Directive? Palliat. Med. 2015, 29, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boland, J.W.; Reigada, C.; Yorke, J.; Hart, S.P.; Bajwah, S.; Ross, J.; Wells, A.; Papadopoulos, A.; Currow, D.C.; Grande, G.; et al. The Adaptation, Face, and Content Validation of a Needs Assessment Tool: Progressive Disease for People with Interstitial Lung Disease. J. Palliat. Med. 2016, 19, 549–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardona-Morrell, M.; Hillman, K. Development of a Tool for Defining and Identifying the Dying Patient in Hospital: Criteria for Screening and Triaging to Appropriate aLternative Care (CriSTAL). BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2015, 5, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, K.; Noble, B. Improving the Delivery of Palliative Care in General Practice: An Evaluation of the First Phase of the Gold Standards Framework. Palliat. Med. 2007, 21, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Highet, G.; Crawford, D.; Murray, S.A.; Boyd, K. Development and Evaluation of the Supportive and Palliative Care Indicators Tool (SPICT): A Mixed-Methods Study. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2014, 4, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, E.A.T.; Murray, S.A.; Engels, Y.; Campbell, C. What Tools Are Available to Identify Patients with Palliative Care Needs in Primary Care: A Systematic Literature Review and Survey of European Practice. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2013, 3, 444–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, A.; Girgis, A.; Davidson, P.M.; Newton, P.J.; Lecathelinais, C.; Macdonald, P.S.; Hayward, C.S.; Currow, D.C. Facilitating Needs-Based Support and Palliative Care for People with Chronic Heart Failure: Preliminary Evidence for the Acceptability, Inter-Rater Reliability, and Validity of a Needs Assessment Tool. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 2013, 45, 912–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aromataris, E.; Fernandez, R.; Godfrey, C.M.; Holly, C.; Khalil, H.; Tungpunkom, P. Summarizing Systematic Reviews: Methodological Development, Conduct and Reporting of an Umbrella Review Approach. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellali, I.; Miziou, S.; Dimitriadou-Maninia, D. Typology and Methodology of Reviews in Health Research. Nurs. Care Res. 2022, 2022, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Wiechula, R.; Conroy, T.; Kitson, A.L.; Marshall, R.J.; Whitaker, N.; Rasmussen, P. Umbrella Review of the Evidence: What Factors Influence the Caring Relationship between a Nurse and Patient? J. Adv. Nurs. 2016, 72, 723–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aromataris, E.; Lockwood, C.; Porritt, K.; Pilla, B.; Jordan, Z. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; The PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stow, D.; Spiers, G.; Matthews, F.E.; Hanratty, B. What Is the Evidence That People with Frailty Have Needs for Palliative Care at the End of Life? A Systematic Review and Narrative Synthesis. Palliat. Med. 2019, 33, 399–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElMokhallalati, Y.; Bradley, S.H.; Chapman, E.; Ziegler, L.; Murtagh, F.E.; Johnson, M.J.; Bennett, M.I. Identification of Patients with Potential Palliative Care Needs: A Systematic Review of Screening Tools in Primary Care. Palliat. Med. 2020, 34, 989–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remawi, B.N.; Gadoud, A.; Murphy, I.M.J.; Preston, N. Palliative Care Needs-Assessment and Measurement Tools Used in Patients with Heart Failure: A Systematic Mixed-Studies Review with Narrative Synthesis. Heart Fail. Rev. 2021, 26, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkland, S.W.; Yang, E.H.; Garrido Clua, M.; Kruhlak, M.; Campbell, S.; Villa-Roel, C.; Rowe, B.H. Screening Tools to Identify Patients with Unmet Palliative Care Needs in the Emergency Department: A Systematic Review. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2022, 29, 1229–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawashima, A.; Evans, C.J. Needs-Based Triggers for Timely Referral to Palliative Care for Older Adults Severely Affected by Noncancer Conditions: A Systematic Review and Narrative Synthesis. BMC Palliat. Care 2023, 22, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Z.; Ding, J.; Jiao, J.; Tang, S.; Huang, C. Screening Instruments for Early Identification of Unmet Palliative Care Needs: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2024, 14, 256–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisberg, B. Functional Assessment Staging (FAST). Psychopharmacol. Bull. 1988, 24, 653–659. [Google Scholar]

- Bruera, E.; Kuehn, N.; Miller, M.J.; Selmser, P.; Macmillan, K. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS): A Simple Method for the Assessment of Palliative Care Patients. J. Palliat. Care 1991, 7, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.R.; Mount, B.M.; Strobel, M.G.; Bui, F. The McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire: A Measure of Quality of Life Appropriate for People with Advanced Disease. A Preliminary Study of Validity and Acceptability. Palliat. Med. 1995, 9, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, F.; Downing, G.M.; Hill, J.; Casorso, L.; Lerch, N. Palliative Performance Scale (PPS): A New Tool. J. Palliat. Care 1996, 12, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, C.P.; Porter, C.B.; Bresnahan, D.R.; Spertus, J.A. Development and Evaluation of the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire: A New Health Status Measure for Heart Failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2000, 35, 1245–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emanuel, L.L.; Alpert, H.R.; Emanuel, E.E. Concise Screening Questions for Clinical Assessments of Terminal Care: The Needs Near the End-of-Life Care Screening Tool. J. Palliat. Med. 2001, 4, 465–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, K. The Gold Standards Framework in Community Palliative Care. Eur. J. Palliat. Care 2003, 10, 113–115. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, J.; Racine, E. The Racine Tool: Identifying Patients for Palliative Care in Family Practice. In Proceedings of the 15th International Congress on Care of the Terminally Ill, Montreal, QC, Canada, 19–23 September 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rockwood, K. A Global Clinical Measure of Fitness and Frailty in Elderly People. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2005, 173, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rainone, F.; Blank, A.; Selwyn, P.A. The Early Identification of Palliative Care Patients: Preliminary Processes and Estimates from Urban, Family Medicine Practices. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care 2007, 24, 137–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moss, A.H.; Ganjoo, J.; Sharma, S.; Gansor, J.; Senft, S.; Weaner, B.; Dalton, C.; MacKay, K.; Pellegrino, B.; Anantharaman, P.; et al. Utility of the “Surprise” Question to Identify Dialysis Patients with High Mortality. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2008, 3, 1379–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, A.; Girgis, A.; Currow, D.; Lecathelinais, C. Development of the Palliative Care Needs Assessment Tool (PC-NAT) for Use by Multi-Disciplinary Health Professionals. Palliat. Med. 2008, 22, 956–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissman, D.E.; Meier, D.E. Identifying Patients in Need of a Palliative Care Assessment in the Hospital Setting a Consensus Report from the Center to Advance Palliative Care. J. Palliat. Med. 2011, 14, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, C.T.; Gisondi, M.A.; Chang, C.-H.; Courtney, D.M.; Engel, K.G.; Emanuel, L.; Quest, T. Palliative Care Symptom Assessment for Patients with Cancer in the Emergency Department: Validation of the Screen for Palliative and End-of-Life Care Needs in the Emergency Department Instrument. J. Palliat. Med. 2011, 14, 757–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glajchen, M.; Lawson, R.; Homel, P.; DeSandre, P.; Todd, K.H. A Rapid Two-Stage Screening Protocol for Palliative Care in the Emergency Department: A Quality Improvement Initiative. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 2011, 42, 657–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDaid, P. A Quick Guide to Identifying Patients for Supportive and Palliative Care; NHS: Leeds, UK, 2011.

- Grudzen, C.R.; Stone, S.C.; Morrison, R.S. The Palliative Care Model for Emergency Department Patients with Advanced Illness. J. Palliat. Med. 2011, 14, 945–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoonsen, B.; Engels, Y.; Van Rijswijk, E.; Verhagen, S.; Van Weel, C.; Groot, M.; Vissers, K. Early Identification of Palliative Care Patients in General Practice: Development of RADboud Indicators for PAlliative Care Needs (RADPAC). Br. J. Gen. Pr. 2012, 62, e625–e631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Batiste, X.; Martínez-Muñoz, M.; Blay, C.; Amblàs, J.; Vila, L.; Costa, X.; Villanueva, A.; Espaulella, J.; Espinosa, J.; Figuerola, M.; et al. Identifying Patients with Chronic Conditions in Need of Palliative Care in the General Population: Development of the NECPAL Tool and Preliminary Prevalence Rates in Catalonia. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2013, 3, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quest, T.; Herr, S.; Lamba, S.; Weissman, D. Demonstrations of Clinical Initiatives to Improve Palliative Care in the Emergency Department: A Report From the IPAL-EM Initiative. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2013, 61, 661–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulman, K.A.; Zalenski, R.J.; Johnson, C. Palliative Care Screening in the Emergency Department: 660. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2015, 22, S283–S284. [Google Scholar]

- George, N.; Barrett, N.; McPeake, L.; Goett, R.; Anderson, K.; Baird, J. Content Validation of a Novel Screening Tool to Identify Emergency Department Patients with Significant Palliative Care Needs. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2015, 22, 823–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clegg, A.; Bates, C.; Young, J.; Ryan, R.; Nichols, L.; Ann Teale, E.; Mohammed, M.A.; Parry, J.; Marshall, T. Development and Validation of an Electronic Frailty Index Using Routine Primary Care Electronic Health Record Data. Age Ageing 2016, 45, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, D.E.; Arya, S.; Schmid, K.K.; Blaser, C.; Carlson, M.A.; Bailey, T.L.; Purviance, G.; Bockman, T.; Lynch, T.G.; Johanning, J. Development and Initial Validation of the Risk Analysis Index for Measuring Frailty in Surgical Populations. JAMA Surg. 2017, 152, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotogni, P.; De Luca, A.; Evangelista, A.; Filippini, C.; Gili, R.; Scarmozzino, A.; Ciccone, G.; Brazzi, L. A Simplified Screening Tool to Identify Seriously Ill Patients in the Emergency Department for Referral to a Palliative Care Team. Minerva Anestesiol. 2017, 83, 474–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, B.; Boyd, K.; Steyn, J.; Kendall, M.; Macpherson, S.; Murray, S.A. Computer Screening for Palliative Care Needs in Primary Care: A Mixed-Methods Study. Br. J. Gen. Pr. 2018, 68, e360–e369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrijmoeth, C.; Echteld, M.A.; Assendelft, P.; Christians, M.; Festen, D.; Van Schrojenstein Lantman-de Valk, H.; Vissers, K.; Groot, M. Development and Applicability of a Tool for Identification of People with Intellectual Disabilities in Need of Palliative Care (PALLI). Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2018, 31, 1122–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murtagh, F.E.; Ramsenthaler, C.; Firth, A.; Groeneveld, E.I.; Lovell, N.; Simon, S.T.; Denzel, J.; Guo, P.; Bernhardt, F.; Schildmann, E.; et al. A Brief, Patient- and Proxy-Reported Outcome Measure in Advanced Illness: Validity, Reliability and Responsiveness of the Integrated Palliative Care Outcome Scale (IPOS). Palliat. Med. 2019, 33, 1045–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veldhoven, C.M.M.; Nutma, N.; De Graaf, W.; Schers, H.; Verhagen, C.A.H.H.V.M.; Vissers, K.C.P.; Engels, Y. Screening with the Double Surprise Question to Predict Deterioration and Death: An Explorative Study. BMC Palliat. Care 2019, 18, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakan, G.; Ozen, M.; Azak, A.; Erdur, B. Determination of the Characteristics and Outcomes of the Palliative Care Patients Admitted to the Emergency Department. Int. Emerg. Nurs. 2020, 53, 100934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amado Tineo, J.P.; Vasquez Alva, R.; Huari Pastrana, R.; Huamán Manrique, P.Z.; Oscanoa Espinoza, T. Need for Palliative Care in Patients Admitted to Emergency Departments of Three Tertiary Hospitals: Evidence from a Latin-American City. Palliat. Med. Pr. 2020, 14, 236–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.-F.; Lai, C.-C.; Fu, P.-Y.; Huang, Y.-C.; Huang, S.-J.; Chu, D.; Lin, S.-P.; Chaou, C.-H.; Hsu, C.-Y.; Chen, H.-H. A-qCPR Risk Score Screening Model for Predicting 1-Year Mortality Associated with Hospice and Palliative Care in the Emergency Department. Palliat. Med. 2021, 35, 408–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, R.T.; Petrie, M.C.; Jackson, C.E.; Jhund, P.S.; Wright, A.; Gardner, R.S.; Sonecki, P.; Pozzi, A.; McSkimming, P.; McConnachie, A.; et al. Which Patients with Heart Failure Should Receive Specialist Palliative Care? Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2018, 20, 1338–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, G.K.; Senior, H.E.; Rhee, J.J.; Ware, R.S.; Young, S.; Teo, P.C.; Murray, S.; Boyd, K.; Clayton, J.M. Using Intuition or a Formal Palliative Care Needs Assessment Screening Process in General Practice to Predict Death within 12 Months: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Palliat. Med. 2018, 32, 384–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, P.M.; Ellis-Smith, C.I.; Daveson, B.A.; Ryan, K.; Mahon, N.G.; McAdam, B.; McQuillan, R.; Tracey, C.; Howley, C.; O’Gara, G.; et al. Understanding How a Palliative-Specific Patient-Reported Outcome Intervention Works to Facilitate Patient-Centred Care in Advanced Heart Failure: A Qualitative Study. Palliat. Med. 2018, 32, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulmasy, D.P. A Biopsychosocial-Spiritual Model for the Care of Patients at the End of Life. Gerontol. 2002, 42, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, Z.J.; Xue, S.; Jones, M.P.; Ravindran, A.V. Depression, Anxiety, and Other Mental Disorders in Patients with Cancer in Low- and Lower-Middle–Income Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JCO Glob. Oncol. 2021, 7, 1233–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerullo, G.; Videira-Silva, A.; Carrancha, M.; Rego, F.; Nunes, R. Complexity of Patient Care Needs in Palliative Care: A Scoping Review. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2023, 12, 791–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seven, A.; Sert, H. Anxiety, Dyspnea Management, and Quality of Life in Palliative Care Patients: A Randomized Controlled Trial. FNJN 2023, 31, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batstone, E.; Bailey, C.; Hallett, N. Spiritual Care Provision to End-of-life Patients: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 3609–3624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fradelos, E.C. Spiritual Well-Being and Associated Factors in End-Stage Renal Disease. Sci. World J. 2021, 2021, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langford, C.P.H.; Bowsher, J.; Maloney, J.P.; Lillis, P.P. Social Support: A Conceptual Analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 1997, 25, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Molassiotis, A.; Chung, B.P.M.; Tan, J.-Y. Unmet Care Needs of Advanced Cancer Patients and Their Informal Caregivers: A Systematic Review. BMC Palliat. Care 2018, 17, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, C.; Ingleton, C.; Gott, M.; Ryan, T. Exploring the Transition from Curative Care to Palliative Care: A Systematic Review of the Literature. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2011, 1, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teike Lüthi, F.; Bernard, M.; Vanderlinden, K.; Ballabeni, P.; Gamondi, C.; Ramelet, A.-S.; Borasio, G.D. Measurement Properties of ID-PALL, A New Instrument for the Identification of Patients with General and Specialized Palliative Care Needs. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 2021, 62, e75–e84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, E.; Müller, M.J.; Boehlke, C.; Schäfer, H.; Quante, M.; Becker, G. Screening for Palliative Care Need in Oncology: Validation of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 2024, 67, 279–289.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria | |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Adults (18 years and older) diagnosed with advanced non-malignant chronic conditions potentially associated with palliative care needs | Birth–5 years, Children (6–12 years), adolescents (13–18 years), patients with advanced malignant conditions |

| Intervention/Indicator | Needs assessment tools for identifying palliative care needs | Educational tools or tools used to assess only one domain of the patient’s overall health status, such as pain, delirium, or quality of life |

| Comparison | Not required. Reviews may focus on one or more tools; direct comparisons between tools were included where available, but not mandatory. | |

| Outcome measures | Identifying needs in palliative care | Identifying needs, general and not specifically for palliative care |

| Time | Published within the last 10 years (2014–2024) | |

| Setting | All healthcare settings | |

| Study characteristics | Systematic reviews and meta-analyses (secondary material). | Systematic review protocol, evaluation of poor quality (lacking a study selection flowchart and explicit inclusion/exclusion criteria), and grey literature. |

| Language of publication | Abstract in English, full text in English or Greek. | |

| Search ID | Search Term | Results |

|---|---|---|

| #1 | MeSH descriptor: [Palliative Care] explode all trees | 2282 |

| #2 | MeSH descriptor: [Hospice Care] explode all trees | 163 |

| #3 | MeSH descriptor: [Hospice and Palliative Care Nursing] explode all trees | 78 |

| #4 | MeSH descriptor: [Advance Care Planning] explode all trees | 429 |

| #5 | MeSH descriptor: [Terminal Care] explode all trees | 707 |

| #6 | MeSH descriptor: [Health Services Needs and Demand] explode all trees | 631 |

| #7 | MeSH descriptor: [Needs Assessment] explode all trees | 480 |

| #8 | MeSH descriptor: [Systematic Review] explode all trees | 426 |

| #9 | MeSH descriptor: [Meta-Analysis as Topic] explode all trees | 1460 |

| #10 | (meta analys *): ti,ab,kw OR (meta synthes *): ti,ab,kw OR (systematic review *): ti,ab,kw OR (review *): ti,ab,kw | 5546 |

| #11 | (Diagnostic tool *): ti,ab,kw OR (Identification tool *): ti,ab,kw OR (Needs assessment tools *): ti,ab,kw OR (Instruments): ti,ab,kw | 884 |

| #12 | (#1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5) AND (#6 OR #7 OR #11) | 22 |

| #13 | #12 AND (#8 OR #9 OR #10) | 5 |

| Authors, Year, Journal | Study Design And Aim | Number and Name of Searched Databases | Search Period | Number of Included Studies | Number and Name of Included Needs Assessment Tools * | Psychometric Properties of Needs Assessment Tools |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [32]; BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care | Study design: systematic literature review Aim: To document what tools to use to identify patients with palliative care needs are available in the published literature, and to ascertain how GPs in Europe currently identify patients for palliative care | 2 (PubMed, Embase) | From Inception up to the end of April 2012 | 5 | 7 (NECPAL; GSF-PIG; SPICT; RADPAC; Residential home palliative care tool; Rainone; QUICK GUIDE) | NR |

| [39]; Palliative Medicine | Study design: Systematic review and narrative synthesis Aim: To synthesize evidence on the end-of-life care needs of people with frailty. | 14 (CINAHL, Cochrane, Embase, EThOS, Google, Medline, NDLTD, NHS Evidence, NICE, Open grey, PsycINFO, SCIE, SCOPUS, Web of Science | From inception up to October 2017 | 20 | 4 (CSHA-CFS; GSF frailty criteria; NECPAL; RAI) | NR |

| [40]; Palliative Medicine | Study design: Systematic review Aim: To identify existing needs assessment tools for the identification of patients with advanced non-malignant chronic conditions who are likely to have Palliative care needs in primary healthcare and evaluate their accuracy. | 4 (Cochrane, MEDLINE, Embase, and CINAHL) | From inception up to March 2019 | 8 | 10 (SPICT; NECPAL; RADPAC; GSF-PIG; PALLI; SQ; The double SQ; AnticiPal electronic tool; Racine tool; eFI) | NR |

| [41]; Heart Failure Reviews | Study design: systematic mixed-studies review with narrative synthesis Aim: To identify the most appropriate palliative care needs-assessment/measurement tools for patients with heart failure | 6 (Cochrane Library, MEDLINE Complete (EBSCO), AMED (EBSCO), PsycINFO (EBSCO), CINAHL Complete (EBSCO), and EMBASE (Ovid) | From inception up to 25 June 2020 | 27 | 6 (IPOS; GSF-PIG; RADPAC; SPICT; NAT:PD-HF; NECPAL) | They are reported |

| [42]; Academic Emergency Medicine | Study design: Systematic review Aim: To identify and assess the psychometric properties of the available needs assessment tools to identify patients with potential palliative care needs in the emergency department (ED). | 7 (OVID Medline, Ovid EMBASE, OVID Health and Psychosocial Tools, EBSCO-CINAHL, SCOPUS, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global, Cochrane Library, and PROSPERO) | Searches were last updated in August 2021 | 35 | 12 (SQ and Modified SQ; P-CaRES and Modified P-CaRES; The SPEED tool and The 5-item SPEED tool; Palliative care trigger tool; Battery of tests including: NEST-13, ESAS, MQOL Questionnaire, Two-stage BriefPal screening protocol; IPAL-EM screening tool; Palliative Screening Tool (Unamed); 7-item Palliative care screening; SST; The Criteria for Receiving Palliative Care; Palliative Care Tool -Unamed; A-qCPR risk score) | They are reported |

| [43]; BMC Palliative Care | Study design: Systematic review and narrative synthesis Aim: to identify and synthesize eligibility criteria for trials in palliative care to construct a needs-based set of triggers for timely referral to palliative care for older adults severely affected by advanced non-malignant chronic conditions. | 6 (MEDLINE (Ovid), EMBASE (Ovid), CINAHL (EBSCOhost), PsycINFO (Ovid), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), and Clinical- Trials.gov) | From inception up to June 2022 | 27 | 6 (PPS; KCCQ; FAST; PC-NAT; CSHA-CFS; SQ) | NR |

| [44]; BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care | Study design: Systematic review and meta-analysis Aim: (1) to identify the screening tools used by health professionals to promote the early identification of patients who may benefit from palliative care and (2) to assess the psychometric properties and clinical performance of the tools. | 6 Four English databases (PubMed, CINAHL, Embase, Scopus) and two Chinese databases (CNKI and Wanfang) | From inception up to May 2023. | 31 | 7 (GSF-PIG; RADPAC; TW-PCST; NECPAL; SPICT; Rainone; AnticiPal) | They are reported |

| Needs Assessment Tools/Year and Country of Development/Available Language Versions | Original Reference | Target Population | Scope | Setting | Type/ Form (Paper-Based/Electronic Tool) | Completed by | Action/ Follow-Up Section Included? | Average Time for Completion | Indicators or Themes/Domains | Inclusion SQ | Criteria for Palliative Care/ Cutoff Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FAST/ 1988, USA/English | [45] | Dementia (end-stage) | Disease-specific | Hospice settings | Paper-based | Healthcare professionals, Carers, and Family members | No—Purely observational or scoring tools. | NR | functional abilities, including physical (dressing and grooming), language (memory and recognition), mobility or self-feeding and other tasks | NO | No cutoff point. Generally, a FAST score of 7A (Stage 7A: Speech limited to about half a dozen intelligible words) or higher indicates end-stage dementia, requiring end-of-life care. |

| ESAS/ 1991, Canada/ English, Spanish, Korean, Italian, Turkish, Japanese, Portuguese, Chinese, French, Danish, German, Hungarian, Icelandic, Hebrew, Russian, Arabic, Dutch, Polish, Swedish, Thai, English Afrikaans | [46] | Multiple advanced chronic conditions | General | Multiple sites | Paper-based | Healthcare professionals, Patients, Family caregivers | No—Used for symptom tracking; no action/follow-up documentation built in. | Less than 2 min | Severity of physical and mental symptoms of distress | NO | No cutoff point. Provides a clinical profile of symptom severity over time. |

| MQOL Questionnaire/ 1995, Canada/ English and translated into more than 20 languages, among which Spanish, French, and Chinese | [47] | Life-threatening illness (any condition) | General | Multiple sites | Paper-based | Healthcare professionals | No—Focused on quality-of-life measurement only. | NR | Self-rating QOL on a scale of 0–10, with four subscales: physical symptoms, psychological symptoms, outlook on life, meaningful existence | NO | NR |

| PPS/ 1996, Canada/ Arabic, Catalan, Chinese, Czech, Dutch, English, Estonia, French, German, Greek, India, Indonesia, Japanese, Polish, Portuguese, Spanish, Thai, Turkish | [48] | Advanced cancer, dementia, frailty, etc. | General | Long-term care (LTC), Hospital | Paper-based | Registered staff to PSWs, Nurses, Physicians, Respiratory Therapists, Physiotherapists, Occupational Therapists, dieticians, pastoral, social workers, counselors, volunteers, family, patients | No—Purely observational or scoring tools. | NR exactly (The tool is quick and easy to use) | Five functional dimensions: ambulation, activity level, evidence of disease, self-care, oral intake, and level of consciousness | NO | 11 levels (0–100% in 10% increments). A PPS score of 70% or below may indicate hospice eligibility. |

| KCCQ/ 2000, USA/Spanish French German Italian, Portuguese Dutch Japanese Chinese (Mandarin) Korean Turkish | [49] | Heart Failure | Disease-specific | Multiple sites | Paper-based | Healthcare professionals, Patients | No—Purely observational or scoring tools. | NR | Physical limitations, symptoms (frequency, severity, change over time), social limitations, self-efficacy, quality of life | NO | No cutoff point. Scores from 0–100, summarized in 25-point ranges (0–24: very poor to poor; 25–49: poor to fair; 50–74: fair to good; 75–100: good to excellent). |

| NEST-13/ 2001, USA/ English | [50] | Multiple comorbidities | General | Clinical settings, Emergency department | Paper-based | Healthcare professionals, Patients | Possibly—Highlights needs across domains; no explicit action section, but designed to guide care discussions. | NR | Thirteen domains: financial, access to care, caregiving, illness distress, physical health, mental health, closeness, spirituality, settledness, purpose, patient/provider communication, information, goals of care | NO | No cutoff point. Aims to assist physicians in identifying specific patient needs |

| GSF-PIG/ 2003, UK/English, Italian | [51] | Cancer, CHF, COPD, frailty | Mixed | Multiple sites | Paper-based | Healthcare professionals | No—Includes SQ and indicators but lacks a dedicated action section. | NR | 73 indicators: 12 general, 12 sets of specific indicators | YES | SQ+, ≥1 general indicator or ≥1 specific indicator) |

| Racine tool/ 2004, Canada/ English | [52] | All * | General | Primary care | Electronic tool | Healthcare professionals | NA | NR | NR | Patient included if electronic records contain at least one high-risk death marker within the next year (e.g., age > 75, diagnosis of congestive heart failure) | |

| CSHA-CFS/ 2005, Canada/ Arabic, Czech, Chinese, Danish, Dutch, Estonian, Finnish. French, German, Greek, Italian, Japanese, Korean, Latvian, Lithuanian, Norwegian, Polish, Portuguese, Slovene, Spanish, Swedish, Turkish | [53] | Frailty (65+) | Disease-specific | Hospital/Emergency department | Paper-based | Healthcare professionals | No—Purely observational or scoring tools. | Less than 2 min | 70 deficits, including presence and severity of current diseases, ability in ADLs, physical signs from clinical and neurologic exams. Specific domains: comorbidity, function, cognition, generating a frailty score | NO | No cutoff point. The highest grade of the CFS (level 9), incorporated both severe frailty and terminal illness |

| Rainone/ 2007, USA/ NA | [54] | All * | General | General practice | Electronic tool | Healthcare professionals | No—Includes SQ and other risk factors but no formal follow-up documentation. | NR | 6 indicators in total | YES | The SQ response was ‘No’ and/or answer affirmatively to any of items 2~5 |

| SQ/ 2008, USA/ English, Italian | [55] | All * | General | Primary care, Hospital | Paper-based | Healthcare professionals | No—A single prognostic question; no action mechanism. | NR (one question) | NA | YES | Answer “no” to the ‘surprise’ question |

| PC-NAT/ 2008, USA/ English | [56] | Cancer, Parkinson’s disease | Disease-specific | Multiple sites (generalist abd specialist care) | Paper-based | Healthcare professionals | Possibly—Focuses on referral and family needs but unclear if it includes explicit post-assessment action plan. | NR | Patient well-being: Physical, Psychological, Spiritual. Caregiver/family ability to care for patient: Physical, Psychological, Family and relationships. Referral to SPCS | NO | NR |

| Palliative care trigger tool/ 2011, USA/ English | [57] | Elderly, multi-organ failure | General | Emergency department | Paper-based | Nurse practitioner | No—Identifies needs; no built-in action tracking. | NR (Three questions) | Three questions include: (1) “Does this patient have a progressive incurable illness that is in its later stages” (2) Do you know if the patient is expected to die on this hospital admission? (3) Would you be surprised if this patient were to die in the next year? Additional items assessing the medical necessity for palliative care and the need for advanced care planning | YES | Positive response (one or more) to any triggers indicates potential palliative care needs |

| SPEED (original version and a modified version-The 5-item SPEED)/ 2011, USA/ English | [58] | Advanced HF, cancer | General | Emergency department | Paper-based | Healthcare professionals | Yes—Especially in its modified version, includes practical care planning elements (e.g., pain management, psychological support). | NR | Original version: 13 items (social, therapeutic, physical, psychological, spiritual needs). Modified version: 5 items (pain management, home care, medication management, psychological support, goals of care): 5 items regarding difficulties in pain management, home care, medication management, psychological support, and goals of care | NO | No cutoff point. Aims to assist physicians in identifying specific patient needs. |

| Two-stage BriefPal screening protocol/ 2011, USA/ English | [59] | Elderly with life- threatening conditions ** | General | Emergency department | Paper-based | Healthcare professionals, Palliative specialists | Possibly—Second stage includes care planning tools, though no structured documentation section reported. | NR | Initial Screening Stage and Comprehensive Assessment Stage. Needs assessment tools: Karnofsky Performance Scale Index, Functional Assessment Staging Tool, Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale, Katz ADL Scale, Brief Assessment Scale for Caregivers | NO | Karnofsky score < 80 or loss of ADLs identified as in need of palliative consultation. |

| QUICK GUIDE/ 2011, UK/ English | [60] | Various chronic diseases | Mixed | Primary care | Paper-based | GPs | No—Designed for early identification; no follow-up or care planning section included. | NR | General indicators (functional status, weight loss, hospital admissions) and disease-specific indicators | YES | Functional status: In bed >50% of the day MRC breathlessness scale 4/5 (REF), NYHA grade 3/4 (REF), WHO performance grade 3/4 (REF) Weight loss: >10% in 3–6 months Hospital admissions: >2 in the last 6 months Other: One or more life-threatening illness Burden of illness (physical, psychological, financial, other) |

| Palliative screening tool (Unnamed)/ 2011, USA/ English | [61] | Multiple advanced conditions | General | Emergency department | NR | Healthcare professionals | No—Screening-focused; lacks formal follow-up documentation. | NR | NR | NR | Patients with one or more triggers identified by an ED physician are considered to have potential palliative care needs. |

| RADPAC/ 2012, The Netherlands/ Dutch | [62] | CHF, COPD, cancer | General | Primary care/general practice | Paper-based | Primary care practitioners | No—Purely observational or scoring tools. | NR | 21 indicators in 3 categories: Disease-specific indicators (COPD, CHF, Cancer), General indicators, SQ, functional status), Indicators of declining health status (psychosocial and caregiver indicators) | NO | No cutoff point |

| NECPAL/ 2013, Spain/English, Spanish, Portugues, Israeli | [63] | Multiple advanced chronic conditions | Mixed | Multiple sites | Paper-based | Healthcare professionals | No—Acts as early identification; no formal action section, though may guide care planning. | Older version: 2–8 min | 59 indicators: 12 general, 9 sets of specific indicators | YES | SQ+, and ≥1 general indicator or ≥1 specific indicator |

| IPAL-EM screening tool/ 2013, USA/ NA | [64] | Life-threatening conditions ** | General | Emergency department | Paper-based | Healthcare professionals | No—Identifies needs; no built-in action tracking. | NA | Symptom burden, functional status, psychosocial concerns, goals of care | NR | No cutoff point. |

| NAT: PD-HF/ 2013, USA/ English, Dutch, German | [33] | Heart Failure | Disease-specific | Multiple sites | Paper-based | Healthcare professionals | Yes—Includes a specific section prompting documentation of actions taken after assessment. | 5–10 min. (Dutch version: 26 min) | 30-item survey assessing needs across four subscales: physical, psychological, social, and existential. | NO | NR |

| SPICT/ 2014, UK/English, Thai, Spanish, Italian, German, Swedish, Indonesian, Danish, Japanese, Nepali, Dutch, French, Greek, Portuguese | [31] | Cancer, Heart/vascular disease, Kidney disease, Dementia/frailty, Respiratory disease, Liver disease, Neurological disease | Mixed | Multiple sites | Paper-based | Healthcare professionals | No—Primarily identification; follow-up left to clinician’s discretion. | SPICT: A few minutes. SPICT-LIS: An average of 3.3 min; SPICT-ES: An average of 4 min and 45 s.; SPICT-DE: An average of 7.5 min | 34 indicators: 6 general, 23 specific clinical, 5 recommended | NO | ≥2 general indicators and ≥1 clinical indicators |

| 7-item Palliative care screening/ 2015, USA/ English | [65] | Advanced conditions, frequent admissions | General | Emergency department | NR | NR | No—Risk-based identification only; follow-up process not included. | NR | NR | NR | Patients with one or more risk factors were identified as having potential palliative care needs. |

| P-CaRES tool (original version and modified version)/ 2015, USA/English | [66] | End-stage chronic conditions | Mixed | Emergency department | Paper-based | Healthcare professionals | Possibly—Includes criteria that imply action, but not a structured follow-up documentation section. | NR (two questions) | The first domain asks physicians to identify at least one end-of-life condition. The second domain includes frequent hospital visits, uncontrolled symptoms, functional decline, uncertainty about goals of care, caregiver distress, and the SQ (“You would not be surprised if this patient died within 12 months”). | YES | Patients with at least one EOL condition and two or more risk factors for potential palliative care needs were identified as having palliative care needs. |

| eFI/ 2016, UK/ NA | [67] | All * | General | Primary care | Electronic tool | GPs | No—Electronic frailty score; does not include any structured care planning section. | NA | ΝA | NO | No cutoff point. It presents an output as a score indicating the number of deficits present out of a possible total of 36, with higher scores indicating an increasing likelihood of a person living with frailty and, hence, vulnerability to adverse outcomes. |

| RAI/ 2017, USA/ English | [68] | Frailty of the surgical patient | Disease-specific | Hospital | Paper-based | Healthcare professionals | No—Scoring tool only; does not include post-assessment action tracking. | NR | 14-item tool assessing deficits across five domains of frailty (physical, functional, social, nutritional, and cognitive). | NO | The RAI score ranges from 0 to 81, and a cutoff of 30 was chosen based on prior work that identified this value as optimal for maximizing negative predictive value. |

| SST/ 2017, Italy/ English | [69] | chronic organ failure (i.e., heart, lungs, liver, and kidneys), progressive neurological diseases (i.e., dementia, stroke, Parkinson’s disease, ALS, MS, and advanced cancer | General | Emergency department | Paper-based | Healthcare professionals | No—Applies inclusion criteria; no documentation section for interventions. | NR | The first criterion refers to the PPS score (0–100). The second criterion refers to the presence of at least one of six clinical indicators, including ≥1 admission within the last 12 months; hospital admission from healthcare services; awaiting admission to long-term care, healthcare services, or hospice; dialysis; home oxygen use; or non-invasive ventilation. | YES | When the Palliative Performance Scale < 50 is present with at least one of these indicators: ≥1 admission within the last 12 months; hospital admission from HCS; awaiting admission to HCS/Hospice; dialysis; home oxygen use; non-invasive ventilation. |

| Anticipate/ 2018, UK/ English | [70] | All * | General | Primary care/General practice | Electronic tool | Healthcare professionals | Possibly—Electronic flags may trigger actions, but no structured follow-up documentation was reported. | NR | NR | NA | if one or more Inclusion criteria are met, None of the exclusion criteria are met. The Inclusion criteria: Type 1: Malignancy codes, e.g., pancreatic cancer. Type 2: Other single Read Codes at any time, e.g., Frailty. Type 3: Combinations of Read Codes, e.g., difficulty swallowing and dementia |

| PALLI/ 2018, The Netherlands/ Dutch, English | [71] | Intellectual disabilities | Disease-specific | Primary care | Paper-based | Healthcare professionals | Possibly—Used to inform decisions in intellectual disability care; unclear whether structured follow-up is recorded. | The mean time of 10.5 min (physicians) and 10.1 min (daily care professionals) | 39 items categorized into nine themes (physical, activities, characteristic behavior, statements of people with intellectual disabilities and family regarding decline, signs and symptoms, recurrence of infections, frailty, serious illnesses, and prognosis). | NO | No cutoff point |

| IPOS (original version), IPOS Neuro, IPOS-Dem, IPOS-Renal, IPOS-HF/ 2019, UK, German/ Arabic, Czech, Danish, English, Estonian, French, Greek, Hindi, Italian, Korean, Malay, Myanmar, Persian, Polish, Portuguese, Singapore, Swedish, Turkish | [72] | Various advanced conditions | General | Multiple sites | Paper-based | Healthcare professionals (staff version), Patients and carers (patient version) | No—Does not include a dedicated action section; results are often used but not directly tied to documented clinical response. | Staff version: 2–5 min Patient version: 8 min | 10 questions scored on a scale of 1–4 assessing physical, social, psychological, and spiritual needs | NO | The overall IPOS score ranges from zero to 68. The IPOS score is useful for understanding the patient’s symptoms, concerns, and status at a specific point in time. |

| double SQ/ 2019, The Netherlands/ Dutch, Slovak | [73] | All * | General | Primary care, Hospital | Paper-based | Healthcare professionals | No—Prognostic only; no care planning or follow-up documentation. | NR (two questions) | NA | YES | a combination of SQ1: ‘no’ and SQ2: ‘yes’ |

| The Criteria for Receiving Palliative Care/ 2020, Turkey/ Turkish | [74] | Multiple life-threatening conditions ** | General | Emergency department | Paper-based | Healthcare professionals | No—Scoring-based eligibility tool; does not include an action section. | NR | The four components include: Main Disease Criteria (cancer, advanced COPD, stroke, terminal kidney failure, advanced heart failure, other diseases and conditions that shorten lifespan); Existence of accompanying disease; Determination of patients’ functionality; Applicability of other criteria prepared by the Provincial Directorate of Health. | NR | Patients who scored 3 or higher according to this form were considered as palliative care patients (PCP) |

| Palliative Care Tool-Unamed/ 2020, Peru/ English | [75] | Advanced disease | General | Emergency department | Paper-based | ED physicians | No—Includes SQ and palliative care indicators, but no follow-up action section mentioned. | NR | 7 questions: The SQ: “Would you be surprised if this patient died within one year?”; knowledge of palliative care; need for palliative care; request for PC; use of palliative care; symptom control; presence of caregiver. | YES | A ‘Yes’ response to Question 3 indicated a patient with potential palliative care needs. |

| A-qCPR/ 2021, USA/ NA | [76] | Advanced chronic conditions | General | Emergency Department/Hospital | Paper-based | Healthcare professionals | No—Purely predictive risk score; no post-assessment component. | NR (takes only a few minutes to complete) | Consists of 5 risk factors for mortality: Age (0.05 points per year) (2 points); qSOFA score of 2 or more (1 point); performance score of two or more (2 points); Had DNR (3 points); Had Cancer (4 points). | NA | A score of 9 or more indicates patients with potential palliative care needs. |

| Category | Tools (n = 35) |

|---|---|

| Early-identification tools | GSF-PIG; SPICT; QUICK GUIDE; NECPAL; RADPAC; SQ; double SQ; Palliative Care Trigger Tool; Rainone tool; A-qCPR; Criteria for Receiving Palliative Care (Turkey); SST; Two-stage BriefPal (Screening Stage); 7-item Palliative Care Screening Tool; Palliative Screening Tool (Unnamed, USA); Anticipate; eFI. |

| Comprehensive multidomain assessment tools | PC-NAT; NAT:PD-HF; SPEED (original and 5-item version); IPOS (all versions). |

| Mixed-purpose tools (tools assessing functional status, frailty, QoL, or combining screening with partial needs assessment) | PPS; KCCQ; NEST-13; CSHA-CFS; RAI; TW-PCST; IPAL-EM; Racine Tool; P-CaRES (original and modified versions); PALLI; FAST; ESAS; MQOL Questionnaire. |

| Reference of Systematic Review | Needs Assessment Tool | Reliability | Validity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content Validity | Criterion Validity | Construct Validity | Face Validity | |||

| [41] | NAT: PD-HF (original) | good | good | good | good | good |

| NAT:PD-HF (Dutch) | NR | NR | poor | poor | NR | |

| [42] | 13-item SPEED | good 1 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| SQ | NR | NR | NR | doubtful 2 | NR | |

| Palliative Care Tool-Unamed (Peru) | good 3 | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| [44] | SPICT | good 4 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Italian-SPICT | NR | very good 5 | NR | NR | NR | |

| Israeli-NECPAL | NR | very good 6 | NR | NR | NR | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Karagkounis, C.; Connor, S.; Papadatou, D.; Bellali, T. Evaluating Palliative Care Needs in Patients with Advanced Non-Malignant Chronic Conditions: An Umbrella Review of Needs Assessment Tools. Healthcare 2026, 14, 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010046

Karagkounis C, Connor S, Papadatou D, Bellali T. Evaluating Palliative Care Needs in Patients with Advanced Non-Malignant Chronic Conditions: An Umbrella Review of Needs Assessment Tools. Healthcare. 2026; 14(1):46. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010046

Chicago/Turabian StyleKaragkounis, Chrysovalantis, Stephen Connor, Danai Papadatou, and Thalia Bellali. 2026. "Evaluating Palliative Care Needs in Patients with Advanced Non-Malignant Chronic Conditions: An Umbrella Review of Needs Assessment Tools" Healthcare 14, no. 1: 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010046

APA StyleKaragkounis, C., Connor, S., Papadatou, D., & Bellali, T. (2026). Evaluating Palliative Care Needs in Patients with Advanced Non-Malignant Chronic Conditions: An Umbrella Review of Needs Assessment Tools. Healthcare, 14(1), 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010046