Walking Capacity in Parkinson’s Disease: Test–Retest Reliability of the 6-min Walk Test on a Non-Linear Circuit

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Size

2.2. Participants

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Clinical Evaluation

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lotankar, S.; Prabhavalkar, K.S.; Bhatt, L.K. Biomarkers for Parkinson’s Disease: Recent Advancement. Neurosci. Bull. 2017, 33, 585–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dexter, D.T.; Jenner, P. Parkinson disease: From pathology to molecular disease mechanisms. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2013, 62, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolosa, E.; Garrido, A.; Scholz, S.W.; Poewe, W. Challenges in the diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2021, 20, 385–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postuma, R.B.; Berg, D.; Stern, M.; Poewe, W.; Olanow, C.W.; Oertel, W.; Obeso, J.; Marek, K.; Litvan, I.; Lang, A.E.; et al. MDS clinical diagnostic criteria for Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2015, 30, 1591–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liepelt-Scarfone, I.; Fruhmann Berger, M.; Prakash, D.; Csoti, I.; Gräber, S.; Maetzler, W.; Berg, D. Clinical characteristics with an impact on ADL functions of PD patients with cognitive impairment indicative of dementia. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e82902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, D.; Solway, S.; Gibbons, W.J. ATS statement on six-minute walk test. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2003, 167, 1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, P.; Romain, A.J.; Vancampfort, D.; Baillot, A.; Esseul, E.; Ninot, G. Six minutes walk test for individuals with schizophrenia. Disabil. Rehabil. 2015, 37, 921–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo-Jáuregui, C.X.; Santos-Martínez, L.E.; López-Mamani, J.J.; Romero-Pozo, M.C.; Contreras-Tapia, I.C.; Aguilar-Valerio, M.T. Six minute walk test in young native high altitude residents. Rev. Medica Inst. Mex. Seguro Soc. 2023, 61, 181–188. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwala, P.; Salzman, S.H. Six-Minute Walk Test: Clinical Role, Technique, Coding, and Reimbursement. Chest 2020, 157, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, H.J.; Jee, S.J.; Lee, M.M. Comparison of Incremental Shuttle Walking Test, 6-Minute Walking Test, and Cardiopulmonary Exercise Stress Test in Patients with Myocardial Infarction. Med. Sci. Monit. Int. Med. J. Exp. Clin. Res. 2022, 28, e938140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanco Pérez, J.J.; Arnalich Montiel, V.; Salgado-Barreira, Á.; Alvarez Moure, M.A.; Caldera Díaz, A.C.; Cerdeira Dominguez, L.; Gonzalez Bello, M.E.; Fernandez Villar, A.; González Barcala, F.J. The 6-Minute Walk Test as a Tool for Determining Exercise Capacity and Prognosis in Patients with Silicosis. Arch. Bronconeumol. 2019, 55, 88–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinovich, R.A.; Vilaró, J.; Roca, J. Evaluation exercise tolerance in COPD patients: The 6-minute walking test. Arch. Bronconeumol. 2004, 40, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramírez Meléndez, A.; Arias Vázquez, P.I.; Lucatero Lecona, I.; Luna Garza, R. Correlation between the six-minute walk test and maximal exercise test in patients with type ii diabetes mellitus. Rehabilitacion 2019, 53, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Díaz, S.N.; Partida-Ortega, A.B.; Macías-Weinmann, A.; Arias-Cruz, A.; Galindo-Rodríguez, G.; Hernández-Robles, M.; Ibarra-Chávez, J.A.; Monge-Ortega, O.P.; Ramos-Valencia, L.; Macouzet-Sánchez, C. Evaluation of functional capacity by 6-minute walk test in children with asthma. Rev. Alerg. Mex. 2017, 64, 415–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanco, I.; Villaquirán, C.; Valera, J.L.; Molina-Molina, M.; Xaubet, A.; Rodríguez-Roisin, R.; Barberà, J.A.; Roca, J. Peak oxygen uptake during the six-minute walk test in diffuse interstitial lung disease and pulmonary hypertension. Arch. Bronconeumol. 2010, 46, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falvo, M.J.; Earhart, G.M. Reference equation for 6-minute walk in individuals with Parkinson disease. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 2009, 46, 1121–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Üğüt, B.O.; Kalkan, A.C.; Kahraman, T.; Dönmez Çolakoğlu, B.; Çakmur, R.; Genç, A. Determinants of 6-minute walk test in people with Parkinson’s disease. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2023, 192, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, V.B.d.; Coertjens, M.; Matos, L.M.; Franzoni, L.T.; Peyré-Tartaruga, L.A.; Passos-Monteiro, E. Asociación entre los estadios de la enfermedad de Parkinson y la clasificación del rendimiento locomotor: Un estudio piloto. Rev. Bras. Ciênc. Esporte 2025, 47, e20240071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanegusuku, H.; Ritti-Dias, R.M.; Barbosa, P.Y.I.; das Neves Guelfi, E.T.; Okamoto, E.; Miranda, C.S.; de Paula Oliveira, T.; Piemonte, M.E.P. Influence of motor impairment on exercise capacity and quality of life in patients with Parkinson disease. J. Exerc. Rehabil. 2021, 17, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen Daalen, J.; van der Heiden, M.; Meinders, M.; Post, B. Motor Symptom Variability in Parkinson’s Disease: Implications for Personalized Trial Outcomes? Mov. Disord. 2025, 40, 975–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, H.; Ge, S.; Li, J.; Jiao, C.; Ran, L. Effects of aerobic and resistance training on walking and balance abilities in older adults with Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0314539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zajac, J.A.; Cavanaugh, J.T.; Baker, T.; Duncan, R.P.; Fulford, D.; Girnis, J.; LaValley, M.; Nordahl, T.; Porciuncula, F.; Rawson, K.S.; et al. Does clinically measured walking capacity contribute to real-world walking performance in Parkinson’s disease? Park. Relat. Disord. 2022, 105, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bean, J.F.; Kiely, D.K.; Leveille, S.G.; Herman, S.; Huynh, C.; Fielding, R.; Frontera, W. The 6-minute walk test in mobility-limited elders: What is being measured? J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2002, 57, M751–M756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailo, G.; Saibene, F.L.; Bandini, V.; Arcuri, P.; Salvatore, A.; Meloni, M.; Castagna, A.; Navarro, J.; Lencioni, T.; Ferrarin, M.; et al. Characterization of Walking in Mild Parkinson’s Disease: Reliability, Validity and Discriminant Ability of the Six-Minute Walk Test Instrumented with a Single Inertial Sensor. Sensors 2024, 24, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquistapace, F.; Piepoli, M.F. The walking test: Use in clinical practice. Monaldi Arch. Chest Dis. 2009, 72, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pulz, C.; Diniz, R.V.; Alves, A.N.; Tebexreni, A.S.; Carvalho, A.C.; de Paola, A.A.; Almeida, D.R. Incremental shuttle and six-minute walking tests in the assessment of functional capacity in chronic heart failure. Can. J. Cardiol. 2008, 24, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngueleu, A.M.; Barrette, S.; Buteau, C.; Robichaud, C.; Nguyen, M.; Everard, G.; Batcho, C.S. Impact of Pathway Shape and Length on the Validity of the 6-Minute Walking Test: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sensors 2024, 25, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancini, M.; Weiss, A.; Herman, T.; Hausdorff, J.M. Turn Around Freezing: Community-Living Turning Behavior in People with Parkinson’s Disease. Front. Neurol. 2018, 9, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, T.K.; Li, M.Y. A Guideline of Selecting and Reporting Intraclass Correlation Coefficients for Reliability Research. J. Chiropr. Med. 2016, 15, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoehn, M.M.; Yahr, M.D. Parkinsonism: Onset, progression and mortality. Neurology 2001, 57, S11–S26. [Google Scholar]

- Venkataraman, A.; Hong, I.Z.; Ho, L.C.; Teo, T.L.; Ang, S.H. Public Perceptions on the Use of the Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timpka, J.; Löhle, M.; Bremer, A.; Christiansson, S.; Gandor, F.; Ebersbach, G.; Dahlström, Ö.; Iwarsson, S.; Nilsson, M.H.; Storch, A.; et al. Objective Observer vs. Patient Motor State Assessments Using the PD Home Diary in Advanced Parkinson’s Disease. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 935664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Patten, R.; Iverson, G.L.; Muzeau, M.A.; VanRavenhorst-Bell, H.A. Test–Retest Reliability and Reliable Change Estimates for Four Mobile Cognitive Tests Administered Virtually in Community-Dwelling Adults. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 734947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merellano-Navarro, E.; Collado-Mateo, D.; García-Rubio, J.; Gusi, N.; Olivares, P.R. Validity of the International Fitness Scale "IFIS" in older adults. Exp. Gerontol. 2017, 95, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkinson, C.; Fitzpatrick, R.; Peto, V.; Greenhall, R.; Hyman, N. The PDQ-8: Development and validation of a short-form Parkinson’s disease questionnaire. Psychol. Health 1997, 12, 805–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdizadeh, M.; Martinez-Martin, P.; Habibi, S.A.; Fereshtehnejad, S.M.; Abasi, A.; Niazi Khatoon, J.; Saneii, S.H.; Taghizadeh, G. Reliability and Validity of Fall Efficacy Scale-International in People with Parkinson’s Disease during On- and Off-Drug Phases. Park. Dis. 2019, 2019, 6505232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rousson, V. Assessing inter-rater reliability when the raters are fixed: Two concepts and two estimates. Biom. J. 2011, 53, 477–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frässle, S.; Stephan, K.E. Test-retest reliability of regression dynamic causal modeling. Netw. Neurosci. 2022, 6, 135–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weir, J.P. Quantifying test-retest reliability using the intraclass correlation coefficient and the SEM. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2005, 19, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffen, T.; Seney, M. Test-retest reliability and minimal detectable change on balance and ambulation tests, the 36-item short-form health survey, and the unified Parkinson disease rating scale in people with parkinsonism. Phys. Ther. 2008, 88, 733–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euser, A.M.; Dekker, F.W.; le Cessie, S. A practical approach to Bland-Altman plots and variation coefficients for log transformed variables. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2008, 61, 978–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, E.; Himuro, N.; Takahashi, M. Clinical utility of the 6-min walk test for patients with moderate Parkinson’s disease. Int. J. Rehabil. Res. 2017, 40, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total (n = 42) Mean ± SD | Men (n = 27) Mean ± SD | Women (n = 15) Mean ± SD | p * | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Height (m) | 1.62 ± 0.08 | 1.72 ± 6.46 | 1.55 ± 8.14 | <0.001 | |

| Weight (kg) | 78.6 ± 15.0 | 81.8 ± 11.7 | 72.7 ± 18.5 | 0.06 | |

| Time since diagnosis (years) | 7.58 ± 5.18 | 7.61 ± 5.54 | 7.53 ± 4.64 | 0.96 | |

| Quality of life PDQ-8 (score 0–32) | 8.48 ± 4.33 | 8.11 ± 4.14 | 9.13 ± 4.73 | 0.47 | |

| Physical Fitness Self-Assessment IFIS (score 0–25) | 13.3 ± 3.16 | 13.6 ± 3.27 | 12.8 ± 2.98 | 0.42 | |

| Fear of falling FES-I (score 16–64) | 30.6 ± 9.37 | 27.5 ± 8.73 | 36.1 ± 8.08 | <0.001 | |

| Total (n = 42) | Men (n = 27) | Women (n = 15) | p ** | ||

| Stages of a disease (levels) (Hoehn & Yahr) | I | 31% | 26.2% | 4.8% | 0.08 |

| II | 54.8% | 33.3% | 21.4% | ||

| III | 14.3% | 4.8% | 9.5% | ||

| Frecuency of Falls | “None” | 61.9% | 42.9% | 19% | 0.06 |

| “Occasionally” | 21.4% | 16.7% | 4.8% | ||

| “Less than once a week” | 14.3% | 2.4% | 11.9% | ||

| “Once a day” | 2.4% | 2.4% | 0% | ||

| “More than once a day” | 0% | 0% | 0% | ||

| Psychopharmacological treatment | “Yes” | 71.4% | 45.2% | 26.2% | 0.75 |

| “No” | 28.6% | 19% | 9.5% |

| Total (n = 42) | Men (n = 27) | Women (n = 15) | p * | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Civil Status | “Married” | 71.4% | 50% | 21.4% | 0.59 |

| “Single” | 11.9% | 7.1% | 4.8% | ||

| “Divorced” | 11.9% | 4.8% | 7.1% | ||

| “Widowed” | 4.8% | 2.4% | 2.4% | ||

| Level of Education | “University” | 14.3% | 11.9% | 2.4% | 0.39 |

| “High School | 19% | 16.7% | 2.4% | ||

| “School graduate” | 45.2% | 23.8% | 21.4% | ||

| “No studies” | 21.4% | 11.9% | 9.5% | ||

| Employment Status | “Active” | 19% | 14.3% | 4.8% | 0.01 |

| “Retired” | 69% | 50% | 19% | ||

| “Unemployed” | 2.4% | 0% | 2.4% | ||

| “Homemaker” | 9.5% | 0% | 9.5% | ||

| Family Status | “Lives alone” | 11.9% | 4.8% | 7.1% | 0.10 |

| “Lives with partner” | 64.3% | 50% | 14.3% | ||

| “Living as a family” | 4.8% | 2.4% | 2.4% | ||

| “Others” | 19% | 71.1% | 11.9% | ||

| 6MWT (m) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Day 1 | Day 2 | ||

| Test Measurement | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | p |

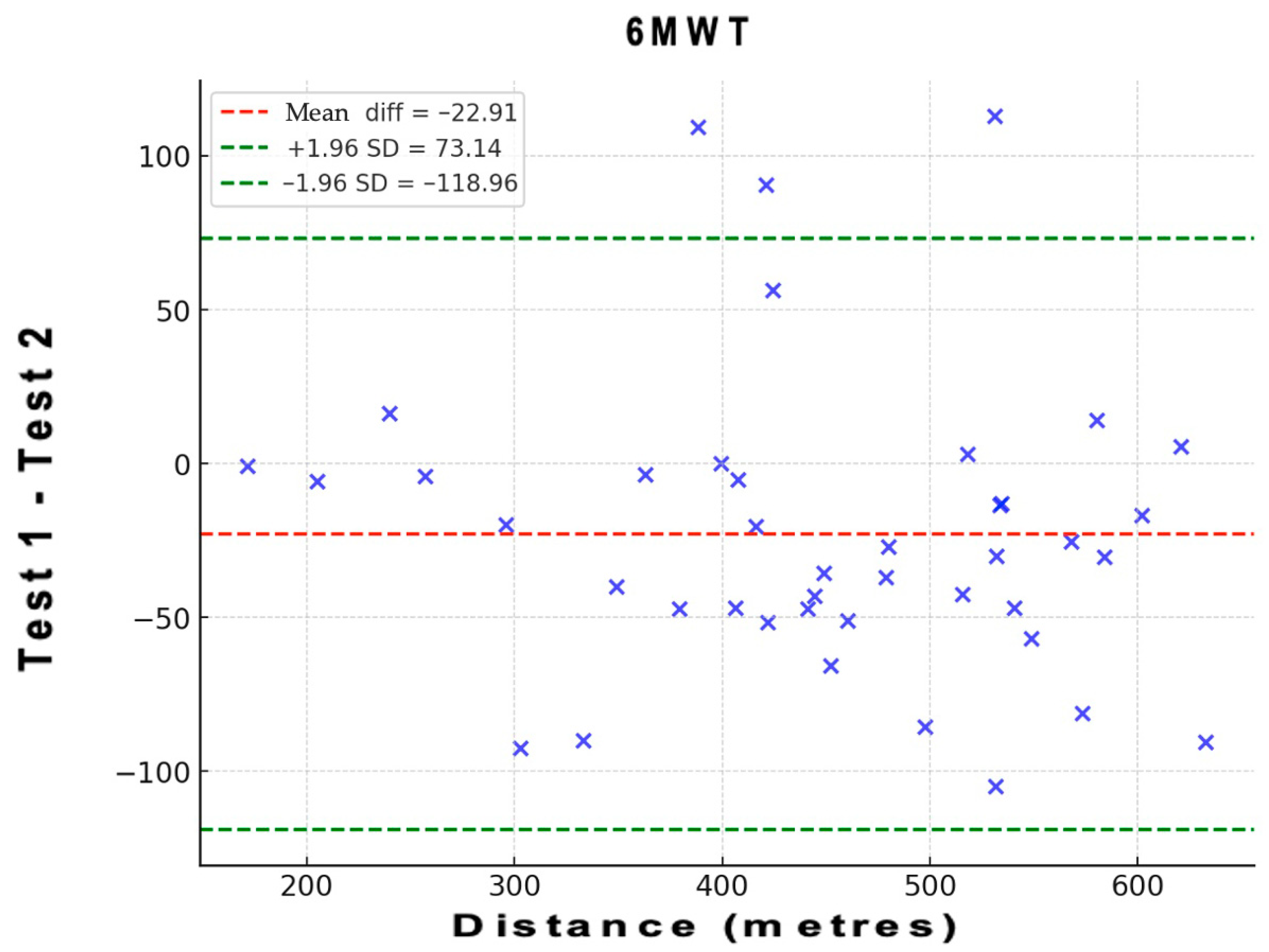

| All participants | 436.92 ± 113.06 | 459.83 ± 119.40 | 0.004 |

| Men | 470.72 ± 102.49 | 499.44 ± 99.45 | 0.007 |

| Women | 376.08 ± 108.43 | 388.55 ± 121.97 | 0.300 |

| Total (n = 42) | 6MWT (m) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assessed Action | ICC (95% CI) | SEM (m) | SEM (%) | MDC (m) | MDC (%) |

| 6MWT (m) | 0.944 (0.897–0.970) | 27.50 | 6.1 | 76.22 | 17 |

| Men (n = 27) | 0.913 (0.810–0.960) | 29.78 | 6.1 | 82.55 | 17 |

| Women (n = 15) | 0.960 (0.885–0.987) | 23.04 | 6.0 | 63.86 | 16.7 |

| r | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | −0.36 | 0.02 * |

| Height (m) | 0.58 | <0.001 * |

| Weight (kg) | 0.04 | 0.81 |

| Time since diagnosis (years) | −0.05 | 0.76 |

| Quality of life PDQ-8 (score 0–32) | 0.10 | 0.53 |

| Physical Fitness Self-Assessment IFIS (score 0–25) | 0.34 | 0.03 * |

| Fear of falling FES-I (score 16–64) | −0.25 | 0.12 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mayoral-Moreno, A.; Chimpén-López, C.A.; Rodríguez-Santos, L.; Ramos-Fuentes, M.I.; Adsuar, J.C.; Caña-Pino, A. Walking Capacity in Parkinson’s Disease: Test–Retest Reliability of the 6-min Walk Test on a Non-Linear Circuit. Healthcare 2026, 14, 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010018

Mayoral-Moreno A, Chimpén-López CA, Rodríguez-Santos L, Ramos-Fuentes MI, Adsuar JC, Caña-Pino A. Walking Capacity in Parkinson’s Disease: Test–Retest Reliability of the 6-min Walk Test on a Non-Linear Circuit. Healthcare. 2026; 14(1):18. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010018

Chicago/Turabian StyleMayoral-Moreno, Asunción, Carlos Alexis Chimpén-López, Laura Rodríguez-Santos, María Isabel Ramos-Fuentes, José Carmelo Adsuar, and Alejandro Caña-Pino. 2026. "Walking Capacity in Parkinson’s Disease: Test–Retest Reliability of the 6-min Walk Test on a Non-Linear Circuit" Healthcare 14, no. 1: 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010018

APA StyleMayoral-Moreno, A., Chimpén-López, C. A., Rodríguez-Santos, L., Ramos-Fuentes, M. I., Adsuar, J. C., & Caña-Pino, A. (2026). Walking Capacity in Parkinson’s Disease: Test–Retest Reliability of the 6-min Walk Test on a Non-Linear Circuit. Healthcare, 14(1), 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010018