Examining Gender Differences and Their Associations Among Psychosocial Distress, Social Support, and Financial Well-Being of Informal Caregivers of Older Adults in the Rural Northcentral United States

Abstract

1. Introduction

Purpose

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Setting and Sample

2.3. Participant Eligibility

2.4. Recruitment Procedures

2.5. Study Measures

2.5.1. Dependent Variable

2.5.2. Independent Variables

2.5.3. Covariates

2.6. Statistical Analysis

2.7. Ethical Considerations

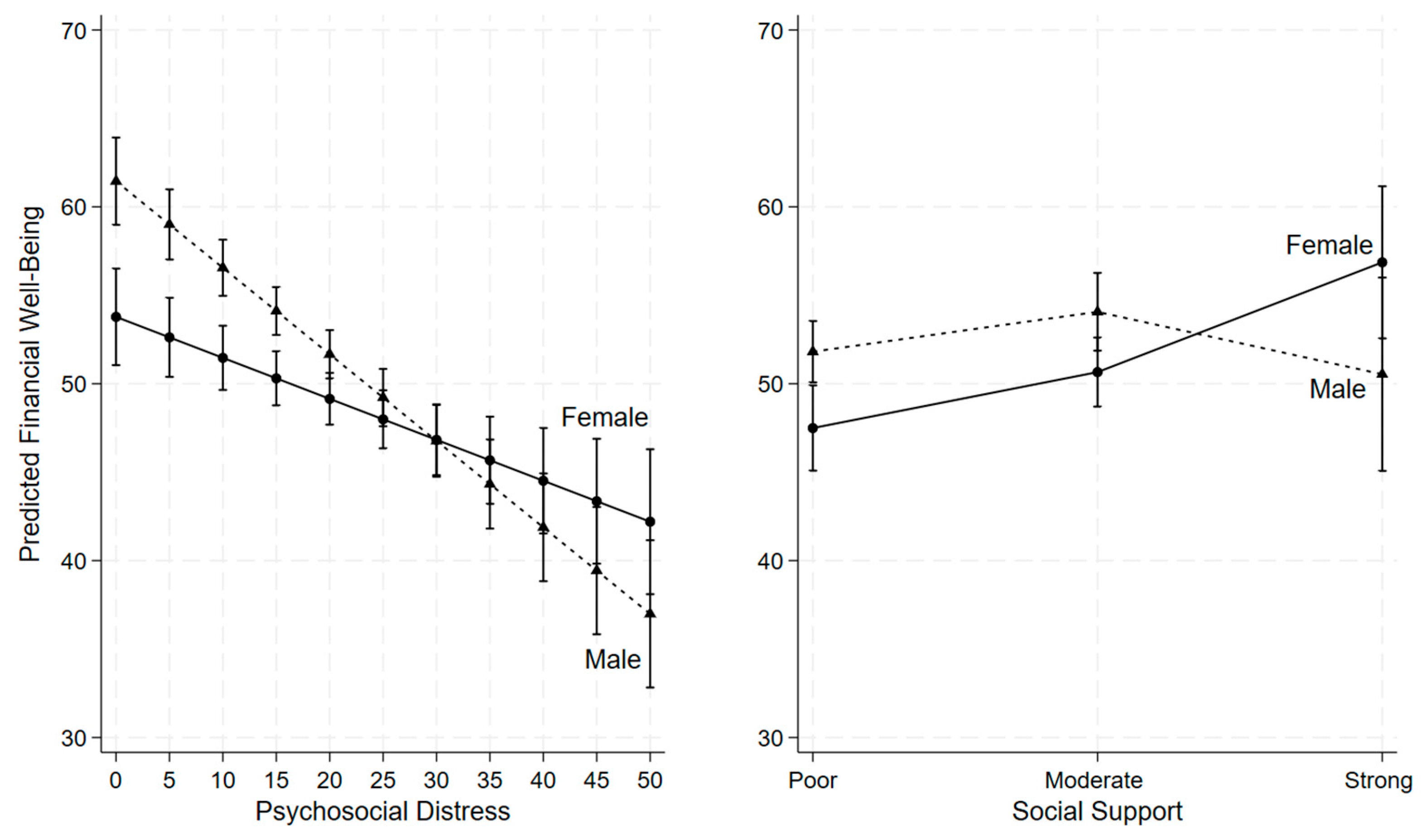

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.1.1. Strengths

4.1.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

6. Practical Implications for Research, Practice, Policy, and Health Education

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hailu, G.N.; Abdelkader, M.; Meles, H.A.; Teklu, T. Understanding the support needs and challenges faced by family caregivers in the care of their older adults at home: A qualitative study. Clin. Interv. Aging 2024, 19, 481–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, A.; Nishida, T.; Ono, M.; Tsukigi, T.; Honda, S. Impact of financial burden on family caregivers of older adults using long-term care insurance services. SAGE Open Nurs. 2025, 11, 23779608251383386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.; Kudaravalli, S.; Kietzman, K.G. Who Is Caring for the Caregivers? The Financial, Physical, and Mental Health Costs of Caregiving in California [Policy Brief]. UCLA Center for Health Policy Research. 2021. Available online: https://healthpolicy.ucla.edu/our-work/publications/who-caring-caregivers-financial-physical-and-mental-health-costs-caregiving-california (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Tahami Monfared, A.A.; Hummel, N.; Chandak, A.; Khachatryan, A.; Zhang, Q. Assessing out-of-pocket expenses and indirect costs for the Alzheimer disease continuum in the United States. J. Manag. Care Spec. Pharm. 2023, 29, 1065–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, N. Family Caregivers Spend More than $7200 a Year on Out-of-Pocket Costs: AARP Study Finds Family Members Feeling Financial Strain from Contributing to Loved Ones’ Care. AARP. 2021. Available online: https://www.aarp.org/caregiving/financial-legal/high-out-of-pocket-costs/ (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- AARP Research. AARP Research Insights on Caregiving, AARP. 2025. Available online: https://www.aarp.org/pri/topics/ltss/family-caregiving/aarp-research-insights-caregiving/ (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- AARP Research; National Alliance for Caregiving. New Report Reveals Crisis Point for America’s 63 million Family Caregivers: 1 in 4 Americans Provide Ongoing, Complex Care; Report Finds They Endure Poor Health, Financial Strain, and Isolation. AARP Press Room. 2025. Available online: https://www.aarp.org/caregivingintheus2025 (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- AARP. AARP Research Shows Family Caregivers Face Significant Financial Strain, Spend on Average $7,242 Each Year: AARP Launches National Campaign Urging More Support for Family Caregivers, Passage of Bipartisan Credit for Caring Act. AARP. 2021. Available online: https://press.aarp.org/2021-6-29-AARP-Research-Shows-Family-Caregivers-Face-Significant-Financial-Strain,-Spend-on-Average-7,242-Each-Year (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Wagle, S.; Yang, S.; Osei, E.A.; Katare, B.; Lalani, N. Caregiving intensity, duration, and subjective financial well-being among rural informal caregivers of older adults with chronic illnesses or disabilities. Healthcare 2024, 12, 2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinhard, S.; Feinberg, L. Caregiver health and well-being, and financial strain. Innov. Aging 2020, 4 (Suppl. 1), 681–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalani, N.; Osei, E.A.; Yang, S.; Katare, B.; Wagle, S. Financial health and well-being of rural female caregivers of older adults with chronic illnesses. BMC Geriatr. 2025, 25, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Family Caregiver Alliance. Caregiver Statistics: Demographics. Family Caregiver Alliance, National Center on Caregiving. 2016. Available online: https://www.caregiver.org/resource/caregiver-statistics-demographics/ (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Mseke, E.P.; Jessup, B.; Barnett, T. Impact of distance and/or travel time on healthcare service access in rural and remote areas: A scoping review. J. Transp. Health 2024, 37, 101819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, M.; Villegas, V.; Winter, K. Bridging the Gap: Rural Health Care Access and the Crucial Role of Broadband Infrastructure. Oregon State University Extension Service. 2024. Available online: https://extension.oregonstate.edu (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Bouldin, E.D.; Shaull, L.; Andresen, E.M.; Edwards, V.J.; McGuire, L.C. Financial and health barriers and caregiving-related difficulties among rural and urban caregivers. J. Rural Health 2018, 34, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Hughes, M.C.; Wang, H. Financial strain, health behaviors, and psychological well-being of family caregivers of older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. PEC Innov. 2024, 4, 100290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poco, L.C.; Andres, E.B.; Balasubramanian, I.; Malhotra, C. Financial difficulties and well-being among caregivers of persons with severe dementia. Aging Ment. Health 2025, 29, 1338–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koomson, I.; Lenzen, S.; Afoakwah, C. Informal care and financial stress: Longitudinal evidence from Australia. Stress Health 2024, 40, e3393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darabos, K.; Faust, H. Assessing health, psychological distress, and financial well-being in informal young adult caregivers compared to matched young adult non-caregivers. Psychol Health Med. 2023, 28, 2249–2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Anuarbe, M.; Kohli, P. Understanding male caregivers’ emotional, financial, and physical burden in the United States. Healthcare 2019, 7, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Caregiving for Family and Friends—A Public Health Issue. National Association of Chronic Disease Directors. 2018. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/healthy-aging-data/media/pdfs/caregiver-brief-508.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Eagly, A.H.; Wood, W. Explaining sex differences in social behavior: A meta-analytic pe rspective. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1991, 17, 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollander, J.A. Vulnerability and dangerousness: The construction of gender through conversation about violence. Gend. Soc. 2001, 15, 83–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurieva, S.D.; Kazantseva, T.V.; Mararitsa, L.V.; Gundelakh, O.E. Social perceptions of gender differences and the subjective significance of the gender inequality issue. Psychol. Russ. State Art 2022, 15, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Graves, B.S.; Hall, M.E.; Dias-Karch, C.; Haischer, M.H.; Apter, C. Gender differences in perceived stress and coping among college students. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0255634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, G.D.; Hebdon, M. Mental health help-seeking behaviour in men. J. Adv. Nurs. 2023, 79, e1–e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åslund, C.; Larm, P.; Starrin, B.; Nilsson, K.W. The buffering effect of tangible social support on financial stress: Influence on psychological well-being and psychosomatic symptoms in a large sample of the adult general population. Int. J. Equity Health 2014, 13, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Measuring Financial Well-Being: A Guide to Using the CFPB Financial Well-Being Scale. Available online: https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201512_cfpb_financial-well-being-user-guide-scale.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Kocalevent, R.D.; Berg, L.; Beutel, M.E.; Hinz, A.; Zenger, M.; Härter, M.; Nater, U.; Brähler, E. Social support in the general population: Standardization of the Oslo social support scale (OSSS-3). BMC Psychol. 2018, 6, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egaña-Marcos, E.; Collantes, E.; Díez-Solinska, A.; Azkona, G. The influence of loneliness, social support, and income on mental well-being. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryu, S.; Fan, L. The relationship between financial worries and psychological distress among U.S. adults. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2023, 44, 16–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S.E.; Cox, S.; Holmes, J.; Angus, C.; Robson, D.; Brose, L.; Brown, J. Paying the price: Financial hardship and its association with psychological distress among different population groups in the midst of Great Britain’s cost-of-living crisis. Soc. Sci. Med. 2025, 364, 117561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pullmann, M.D.; VanHooser, S.; Hoffman, C.; Heflinger, C.A. Barriers to and supports of family participation in a rural system of care for children with serious emotional problems. Community Ment. Health J. 2010, 46, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Humble, M.N.; Lewis, M.L.; Scott, D.L.; Herzog, J. Challenges in rural social work practice: When support groups contain your neighbors, church members, and the PTA. Soc. Work Groups 2013, 36, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, A.; Javed, U.; Hagan, K.; Chang, R.; Kundi, H.; Amin, Z.; Butt, S.; Al-Kindi, S.; Javed, Z. Social determinants of financial stress and association with psychological distress among young adults 18–26 years in the United States. Front. Public Health 2025, 12, 1485513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goddard, I.; Parker, K. Men, Women and Social Connections. Pew Research Center. 2025. Available online: https://pewrsr.ch/42hWLuO (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Aoudi Chance, E.; Abdoul, I.S. The roles and contributions of women to the health of their families and household economics in rural areas in the district of Mbe, Cameroon. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2025, 11, 101456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Z.; Guo, Y.; Zheng, J.; Xie, P. When giving social support is beneficial for well-being? Acta Psychol. 2025, 255, 104911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | N (%) or Mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| Age group | |

| 18–64 years | 377 (70.73%) |

| 65+ years | 156 (29.27%) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 288 (54.03%) |

| Female | 245 (45.97%) |

| Race and ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 472 (88.56%) |

| Non-White | 61 (11.44%) |

| Education level | |

| ≤High school | 182 (34.15%) |

| Some college | 182 (34.15%) |

| College degree or higher | 169 (31.71%) |

| Marital status | |

| Married/Partnered | 300 (56.29%) |

| Never married | 124 (23.26%) |

| Divorced/Widowed/Separated | 109 (20.45%) |

| Annual household income | |

| Less than $20,000 | 95 (17.82%) |

| $20,000 to $49,999 | 184 (34.52%) |

| $50,000 to $74,999 | 115 (21.58%) |

| ≥$75,000 | 139 (26.08%) |

| Caregiving status for older adults | |

| Yes | 196 (36.77%) |

| No | 337 (63.23%) |

| Self-rated health | |

| Poor | 31 (5.82%) |

| Fair | 133 (24.95%) |

| Good | 287 (53.85%) |

| Very Good | 82 (15.38%) |

| Social support | |

| Poor support | 257 (48.22%) |

| Moderate support | 233 (43.71%) |

| Strong support | 43 (8.07%) |

| Psychosocial distress | 17.90 ± 12.16 |

| Financial well-being | 51.49 ± 13.98 |

| N | Mean ± Standard Deviation | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 288 | 52.66 ± 13.83 | 0.036 |

| Female | 245 | 50.12 ± 14.06 | |

| Social support | |||

| Poor support | 257 | 47.46 ± 13.47 | <0.001 |

| Moderate support | 233 | 54.50 ± 12.91 | |

| Strong support | 43 | 59.26 ± 15.44 |

| Outcome: Financial Well-Being | B | p Value | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Gender (ref. Male) | ||||

| Female | −8.93 * | <0.001 | −13.54 | −4.31 |

| Psychosocial distress | −0.49 * | <0.001 | −0.61 | −0.37 |

| Psychosocial distress × Gender | 0.26 * | 0.002 | 0.09 | 0.42 |

| Social support (ref. Poor support) | ||||

| Moderate support | 2.25 | 0.120 | −0.59 | 5.10 |

| Strong support | −1.28 | 0.665 | −7.05 | 4.50 |

| Social support × Gender (ref. Poor support, Male) | ||||

| Moderate support, Female | 0.91 | 0.670 | −3.27 | 5.09 |

| Strong support, Female | 10.64 * | 0.006 | 3.05 | 18.23 |

| Age group (ref. 18–64 years) | ||||

| 65+ years | 7.78 * | <0.001 | 5.45 | 10.12 |

| Race and ethnicity (ref. Non-White) | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | −2.62 | 0.094 | −5.70 | 0.45 |

| Education level (ref. ≤ High school) | ||||

| Some college | −0.51 | 0.665 | −2.85 | 1.82 |

| College degree or higher | 1.94 | 0.134 | −0.60 | 4.48 |

| Annual household income (ref. < $20,000) | ||||

| $20,000 to $49,999 | 1.68 | 0.255 | −1.21 | 4.56 |

| $50,000 to $74,999 | 3.56 * | 0.035 | 0.26 | 6.86 |

| ≥ $75,000 | 5.33 * | 0.002 | 1.89 | 8.78 |

| Marital status (ref. Married/Partnered) | ||||

| Never married | −1.95 | 0.135 | −4.51 | 0.61 |

| Divorced/Widowed/Separated | −2.41 | 0.074 | −5.06 | 0.23 |

| Caregiving status for older adults (ref. No) | ||||

| Yes | 1.21 | 0.243 | −0.82 | 3.24 |

| Self-rated health (ref. Poor/Fair) | ||||

| Good | 0.82 | 0.476 | −1.43 | 3.06 |

| Very good | 3.26 * | 0.048 | 0.03 | 6.50 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lalani, N.; Osei, E.A.; Xu, Z. Examining Gender Differences and Their Associations Among Psychosocial Distress, Social Support, and Financial Well-Being of Informal Caregivers of Older Adults in the Rural Northcentral United States. Healthcare 2026, 14, 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010017

Lalani N, Osei EA, Xu Z. Examining Gender Differences and Their Associations Among Psychosocial Distress, Social Support, and Financial Well-Being of Informal Caregivers of Older Adults in the Rural Northcentral United States. Healthcare. 2026; 14(1):17. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010017

Chicago/Turabian StyleLalani, Nasreen, Evans Appiah Osei, and Zihan Xu. 2026. "Examining Gender Differences and Their Associations Among Psychosocial Distress, Social Support, and Financial Well-Being of Informal Caregivers of Older Adults in the Rural Northcentral United States" Healthcare 14, no. 1: 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010017

APA StyleLalani, N., Osei, E. A., & Xu, Z. (2026). Examining Gender Differences and Their Associations Among Psychosocial Distress, Social Support, and Financial Well-Being of Informal Caregivers of Older Adults in the Rural Northcentral United States. Healthcare, 14(1), 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010017