Composition of Diagnostic Assessment Sheet Items for Developing a Personalized Forest Therapy Program for Patients with Depression: Application of the Delphi Technique

Abstract

1. Introduction

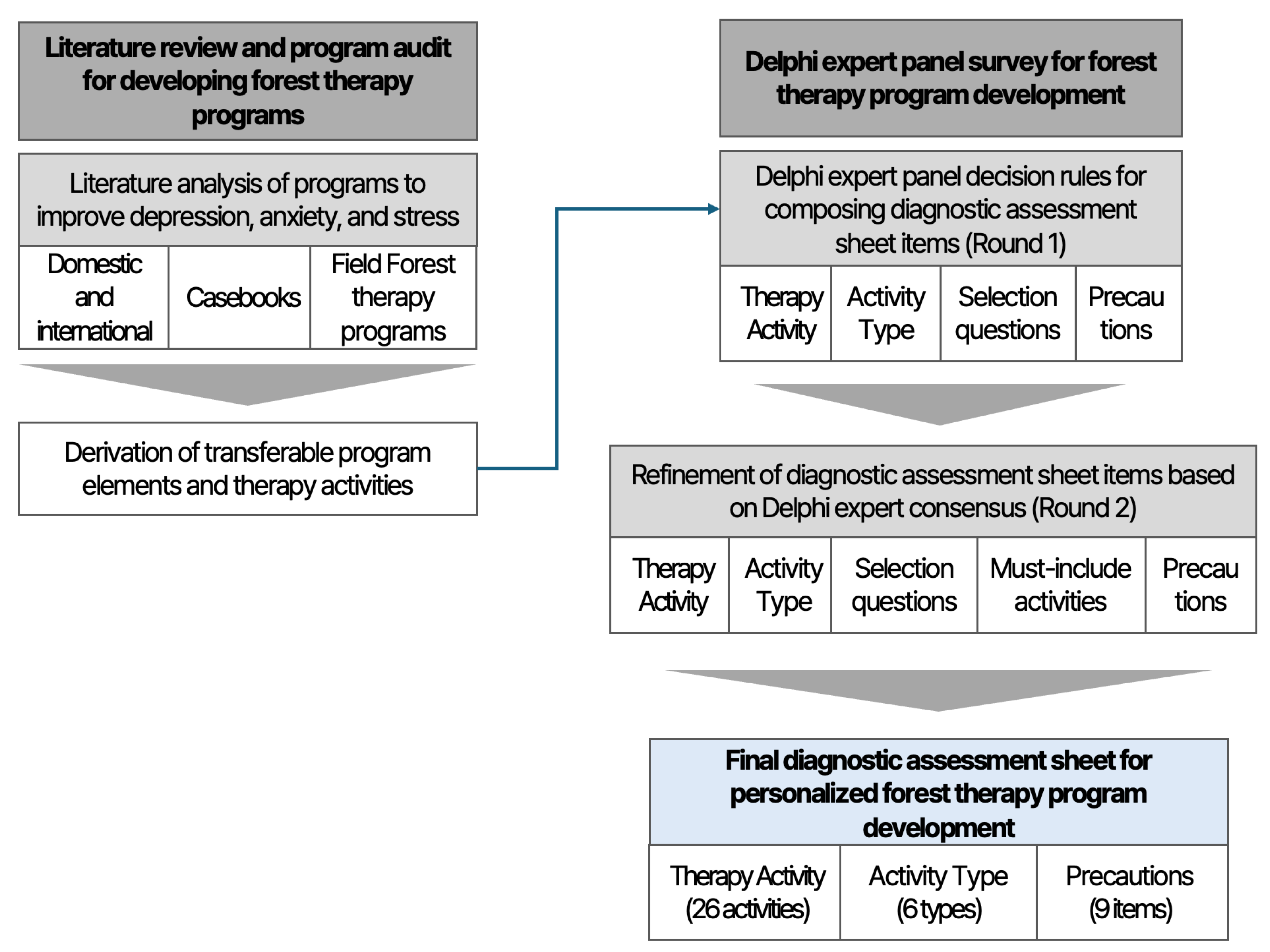

2. Methods

2.1. Study Procedure

2.2. Delphi Survey Questionnaire

2.2.1. Literature Analysis

2.2.2. Derivation of Therapy Activities for Forest Therapy Programs

2.2.3. Construction of the Round 1 Delphi Survey Questionnaire Items

2.2.4. Construction of the Round 2 Delphi Survey Questionnaire

2.3. Composition of the Expert Panel

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Round 1 Delphi Survey Results

3.1.1. Results of Round 1: Selection and Typology of Forest Therapy Activities for Patients with Depression

3.1.2. Results of Round 1: Evaluation Items and Precautions for Selecting Forest Therapy Activity Types

3.1.3. Open-Ended Comments by Item from the Round 1 Delphi Survey

3.1.4. Changes Based on Round 1 Delphi Survey Results

3.2. Results of the Round 2 Delphi Survey

3.2.1. Results of Round 2: Selection and Typology of Forest Therapy Activities for Patients with Depression

3.2.2. Results of Round 2: Evaluation Items and Precautions for Selecting Forest Therapy Activity Types

3.2.3. Open-Ended Comments by Item from the Round 2 Delphi Survey

3.2.4. Changes Based on Round 2 Delphi Survey Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- World Health Organization. Depressive Disorder (Depression). Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression (accessed on 31 March 2023).

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. Suicide Rates. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/data/indicators/suicide-rates.html (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Kim, M.-R.; Park, T.-H.; Oh, H.-Y. A study on the development of an empathic chatbot for alleviating depressive symptoms. J. Korea Inst. Inf. Commun. Eng. 2023, 27, 611–619. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Mental Health. Depressive Disorder. Available online: https://www.mentalhealth.go.kr/portal/disease/diseaseDetail.do?dissId=36 (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- Lee, M.-S. Current status and diagnosis of depression in recent years. J. Pharm. Hosp. Assoc. 2013, 30, 505–511. [Google Scholar]

- Gorman, J.M. Comorbid depression and anxiety spectrum disorders. Depress. Anxiety 1996, 4, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center for Mental Health. 2024 National Survey of Public Knowledge and Attitudes Toward Mental Health; National Center for Mental Health: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.-S.; Kang, D.-Y.; Korean Society for Clinical Pharmacology. Clinical Neuropsychiatric Pharmacology; ML Communication: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Korea Forest Service. Forestry Culture and Recreation Act. Available online: https://elaw.klri.re.kr/kor_service/lawView.do?hseq=27993&lang=ENG (accessed on 20 June 2023).

- Ibes, D.; Hirama, I.; Schuyler, C. Greenspace ecotherapy interventions: The stress-reduction potential of green micro-breaks integrating nature connection and mind–body skills. Ecopsychology 2018, 10, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. Effects of a Self-Guided Forest Therapy Program. Master’s Thesis, Chungbuk National University, Cheongju, Republic of Korea, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rivieccio, R.; Meneguzzo, F.; Margheritini, G.; Re, T.; Riccucci, U.; Zabini, F. Therapist-guided versus self-guided forest immersion: Comparative efficacy on short-term mental health and economic value. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Shen, J.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, Z. The beneficial elements in forest environment based on human health and well-being perspective. Forests 2024, 15, 1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Kobayashi, M.; Wakayama, Y.; Inagaki, H.; Katsumata, M.; Hirata, Y.; Hirata, K.; Shimizu, T.; Kawada, T.; Park, B.J. Effect of phytoncide from trees on human natural killer cell function. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2009, 22, 951–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, J.; Yang, H.; Yoon, M.; Gadhe, C.G.; Pae, A.N.; Cho, S.; Lee, C.J. 3-Carene, a phytoncide from pine trees, has a sleep-enhancing effect by targeting the GABAA-benzodiazepine receptors. Exp. Neurobiol. 2019, 28, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Hong, G.L.; Kim, K.H.; Lee, H.J.; Cho, S.P.; Joung, D.; Pack, B.J.; Jung, J.Y. Effects of phytoncide extracts on antibacterial activity, immune responses, and stress in dogs. J. People Plants Environ. 2023, 26, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donelli, D.; Meneguzzo, F.; Antonelli, M.; Ardissino, D.; Niccoli, G.; Gronchi, G.; Baraldi, R.; Neri, L.; Zabini, F. Effects of plant-emitted monoterpenes on anxiety symptoms: A propensity-matched observational cohort study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudek, T.; Marć, M. Terpene content in the air of younger and older forests in southeastern Poland: Implications for forest therapy. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 42174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, W.-S.; Oh, H.-G. The Influence of the Forest Program on Depression Level. J. Korean For. Soc. 1996, 85, 586–595. [Google Scholar]

- Sin, W.-S.; Yeon, P.-S.; Lee, J.-H.; Kim, S.-G.; Joo, J.-S. Effects of forest experiences on anxiety and depression in participants. J. Korean For. Rec. Sci. 2007, 11, 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, W.; Woo, J.; Park, S.; Lim, S. Effects of forest activities on recovery of patients with depression: A comparative study among forest therapy program group, hospital program group, forest bathing group, and control group. J. Korean For. Sci. Soc. 2012, 101, 677–685. [Google Scholar]

- Yeon, P.; Kim, I.; Kang, S.; Lee, N.; Kim, G.; Min, G.; Chung, C.; Lee, J.; Kim, J.; Shin, W. Effects of urban forest therapy program on depression patients. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 20, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeon, P.; Kang, S.; Lee, N.; Kim, I.; Min, G.; Kim, G.; Kim, J.; Shin, W. Benefits of urban forest healing program on depression and anxiety symptoms in depressive patients. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeon, P.; Jeon, J.; Jung, M.; Min, G.; Kim, G.; Han, K.; Shin, M.; Jo, S.; Kim, J.; Shin, W. Effect of forest therapy on depression and anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Ye, B. Forest therapy in Germany, Japan, and China: Proposal, development status, and future prospects. Forests 2022, 13, 1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Yeon, P. Analysis of Research Trends in Forest Therapy Using LDA Topic Modeling. J. Korean Inst. For. Recreat. 2025, 29, 59–74. [Google Scholar]

- Korea Forest Healing Forum. A Survey of Nature Prescription Cases Related to Forest Healthcare; Korea Forest Healing Forum: Cheongju, Republic of Korea, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Forest Science. Development of Indicators and a Health–Medical Linkage Service Model for Building a Forest Healing Big Data System; NIFoS: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.; Park, Y.; Eun, S.-D.; Ho, S.H. Development of a Set of Assessment Tools for Health Professionals to Design a Tailored Rehabilitation Exercise and Sports Program for People with Stroke in South Korea: A Delphi Study. Healthcare 2023, 11, 3031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, M.-G. Development of a Diagnostic Assessment Tool for Music Therapy for Children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Ph.D. Thesis, Dong-A University, Busan, Republic of Korea, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Lawshe, C.H. A quantitative approach to content validity. Pers. Psychol. 1975, 28, 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.-H.; Jang, J.-H. A Delphi Study to Develop Performance Evaluation Indicators for Occupational Safety and Health Education Projects. HRD Res. 2019, 21, 113–132. [Google Scholar]

- Ayre, C.; Scally, A.J. Critical values for Lawshe’s content validity ratio: Revisiting the original methods of calculation. Meas. Eval. Couns. Dev. 2014, 47, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Yoo, R.; Park, C.; Kim, J. Analysis of activity components in domestic forest therapy programs. In Proceedings of the Korean Forest Recreation Society Conference, Seogwipo, Republic of Korea, 23–26 November 2011; pp. 87–90. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.H.; Jeong, D.W.; Park, B.J. Classification of domestic forest therapy programs. J. Korean Inst. For. Recreat. 2019, 23, 43–58. [Google Scholar]

- Jeon, J.-Y.; Kang, S.-N.; Kim, J.-G.; Yeon, P.-S. Analysis of types of domestic forest therapy programs for improving depression. J. Korean For. Rec. Sci. 2022, 26, 99–115. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins, E.R. Constructive and unconstructive repetitive thought. Psychol. Bull. 2008, 134, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolen-Hoeksema, S. The role of rumination in depressive disorders and mixed anxiety/depressive symptoms. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2000, 109, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.; Kang, S.; Paek, K.; Lee, N.; Min, G.; Seo, Y.; Park, S.; Park, S.; Choi, H.; Choi, S. Analysis of program activities to develop forest therapy programs for improving mental health: Focusing on cases in Republic of Korea. Healthcare 2025, 13, 760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Therapy Activities | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Purpose-driven activities | Discovering my values | Analyzing the problem | Noticing stress |

| Awakening the five senses | Identifying and planning solutions | Expressing stress | |

| Noticing emotions | Implementing and evaluating solutions | Cognitive restructuring and awareness | |

| Expressing emotions | Enhancing social skills | Identifying strengths and weaknesses | |

| Recalling the past | Setting my dreams and goals | Noticing the present | |

| Noticing thoughts | Finding ways to cope and manage stress | Finding happiness | |

| Self-exploration activities | |||

| Practical activities | Assigning tasks | Ice-breaking | Brain stimulation exercise |

| Setting rules | Role play | Forest experiences | |

| Play | Yoga | Insect-mediated activities | |

| Tea ceremony | Cooking activities | Animal-assisted activities | |

| Expressing through movement | Laughter activities | Creative activities | |

| Massage | Music activities | Hydrotherapy activities | |

| Crafting | Self-introduction | Forest walking | |

| Meditation | Playing with natural objects | Forest Literature activities | |

| Literature activities | Dancing | Forest workout | |

| Art activities | Breathing Techniques | Storytelling | |

| Naming (assigning nicknames) | Wrapping up an activity | Video media activity | |

| Stretching | Indoor Gardening | Exercise | |

| Physical relaxation | Outdoor Gardening | Therapy equipment experience | |

| Mind-body training exercise | |||

| Activity Type | Therapy Activities | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Introductory-stage activities | Ice-breaking | Self-introduction | Naming (assigning nicknames) |

| Setting rules | |||

| Sensory stimulation and mind-body relaxation activities | Meditation | Breathing Techniques | Physical relaxation |

| Mind-body training exercise | Stretching | Massage | |

| Tea ceremony | Awakening the five senses | ||

| Self-understanding and problem-solving activities | Discovering my values | Setting my dreams and goals | Noticing stress |

| Noticing emotions | Noticing thoughts | Expressing stress | |

| Expressing emotions | Noticing the present | Analyzing the problem | |

| Recalling the past | Finding happiness | Identifying and planning solutions | |

| Self-exploration activities | Cognitive restructuring and awareness | Implementing and evaluating solutions | |

| Identifying strengths and weaknesses | Finding ways to cope and manage stress | ||

| Social skills and relationship-building activities | Enhancing social skills | Role play | Play |

| Expressing through movement | |||

| Physical activity and exercise | Exercise | Dancing | Yoga |

| Brain stimulation exercise | Forest workout | ||

| Arts and creative activities | Art activities | Crafting | Literature activities |

| Cooking activities | Video media activity | Creative activities | |

| Laughter activities | Music activities | Storytelling | |

| Nature-based activities | Forest experiences | Indoor Gardening | Hydrotherapy activities |

| Forest walking | Outdoor Gardening | Playing with natural objects | |

| Forest literature activities | Animal-assisted activities | Insect-mediated activities | |

| Therapy equipment experience | |||

| Activity wrap-up and real-life linkage activities | Assigning tasks | Wrapping up an activity | |

| Survey Contents |

|---|

(1) Selection and typology of forest therapy activities for patients with depression

(2) Evaluation items and precautions for selecting forest therapy activity types

|

| Survey Contents |

|---|

| (1) Selection and typology of forest therapy activities for patients with depression ① Type appropriateness (O/X response) - Were the 45 therapy activities appropriately classified into the 8 activity types? ② Activity appropriateness (5-point Likert scale) - Is it appropriate to offer the 45 therapy activities as part of a patient-tailored forest therapy program? ③ Must-include activities (5-point Likert scale) - When composing the program, is it appropriate to include ‘introductory-stage activities’ and ‘activity wrap-up and real-life linkage activities’ as mandatory components? (2) Evaluation items and precautions for selecting forest therapy activity types ① Appropriateness of the selection questions for activity types (5-point Likert scale) - Are the content and wording of the diagnostic assessment items for selecting forest therapy activity types appropriate? ② Importance of precautions for composing and implementing forest therapy programs for patients (5-point Likert scale) - Are these necessary items as precautions to consider when composing and implementing forest therapy programs? |

| No. | Field | Gender | Affiliation & Position | Experience (Years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Forest therapy | Female | Director, Research Institute under the Korea Forest Service | 26 |

| 2 | Female | Senior Researcher, Research Institute under the Korea Forest Service | 18 | |

| 3 | Male | Head, Public Institution under the Korea Forest Service | 16 | |

| 4 | Female | Team Leader, Public Institution under the Korea Forest Service | 9 | |

| 5 | Female | Team Leader, Public Institution under the Korea Forest Service | 13 | |

| 6 | Male | Director, National Healing Forest under the Korea Forest Service | 15 | |

| 7 | Female | Ph.D., National Recreational Forest under the Korea Forest Service | 13 | |

| 8 | Male | Professor, Department of Forest Environmental Resources, University | 21 | |

| 9 | Female | Associate Professor, Department of Forest Science, University | 21 | |

| 10 | Male | Assistant Professor, Department of Environmental & Forest Sciences, University | 15 | |

| 11 | Psychiatry | Male | Director, Department of Psychiatry, D Hospital | 9 |

| 12 | Male | Director, Department of Psychiatry, S Hospital | 8 | |

| 13 | Male | Director, Department of Psychiatry, O Hospital | 6 | |

| 14 | Male | Director, Department of Psychiatry, Y Hospital | 10 | |

| 15 | Male | Director, Department of Psychiatry, G Hospital | 3 | |

| 16 | Male | Director, Department of Psychiatry, M Hospital | 25 | |

| 17 | Male | Director, Department of Psychiatry, H Hospital | 12 | |

| 18 | Male | Director, Department of Psychiatry, H Hospital | 8 | |

| 19 | Male | Director, Department of Psychiatry, S Hospital | 8 | |

| 20 | Male | Director, Department of Psychiatry, M Hospital | 12 |

| Type | Sub-Activity | Mean | CVR | Type | Sub-Activity | Mean | CVR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Introductory-stage activities | Ice-breaking | 4.29 | 0.65 | Social skills and relationship-building activities | Enhancing social skills | 4.31 | 0.65 |

| Self-introduction | 4.35 | 0.53 | Expressing through movement | 3.76 | 0.18 | ||

| Naming(assigning nicknames) | 4.00 | 0.29 | Role play | 3.71 | 0.06 | ||

| Setting rules | 4.59 | 0.76 | Play | 4.12 | 0.65 | ||

| Sensory stimulation and mind-body relaxation activities | Meditation | 4.76 | 1.00 | Physical activity and exercise | Exercise | 4.24 | 0.65 |

| Breathing Techniques | 4.88 | 1.00 | Dancing | 3.82 | 0.29 | ||

| Physical relaxation | 4.71 | 1.00 | Yoga | 4.00 | 0.41 | ||

| Mind-body training exercise | 3.82 | 0.29 | Brain stimulation exercise | 3.59 | 0.18 | ||

| Stretching | 4.59 | 0.88 | Forest workout | 4.35 | 0.53 | ||

| Massage | 3.65 | 0.06 | Arts and creative activities | Art activities | 4.06 | 0.53 | |

| Tea ceremony | 3.82 | 0.41 | Crafting | 4.00 | 0.53 | ||

| Awakening the five senses | 4.12 | 0.41 | Literature activities | 4.00 | 0.53 | ||

| Self-understanding and problem-solving activities | Discovering my values | 4.29 | 0.76 | Video media activity | 3.71 | 0.18 | |

| Noticing emotions | 4.47 | 0.76 | Music activities | 3.88 | 0.41 | ||

| Expressing emotions | 4.29 | 0.76 | Laughter activities | 4.00 | 0.53 | ||

| Recalling the past | 3.82 | 0.29 | Creative activities | 3.82 | 0.41 | ||

| Setting my dreams and goals | 4.00 | 0.41 | Cooking activities | 3.94 | 0.41 | ||

| Self-exploration activities | 4.24 | 0.76 | Storytelling | 3.88 | 0.41 | ||

| Noticing thoughts | 4.35 | 0.65 | Nature-based activities | Forest experiences | 4.65 | 0.76 | |

| Noticing the present | 4.24 | 0.65 | Forest walking | 4.76 | 0.88 | ||

| Finding happiness | 4.24 | 0.65 | Forest literature activities | 3.76 | 0.41 | ||

| Identifying strengths and weaknesses | 4.06 | 0.53 | Indoor Gardening | 3.82 | 0.41 | ||

| Noticing stress | 4.18 | 0.88 | Outdoor Gardening | 4.00 | 0.65 | ||

| Expressing stress | 4.06 | 0.65 | Therapy equipment experience | 3.47 | 0.06 | ||

| Finding ways to cope and manage stress | 4.41 | 0.88 | Hydrotherapy activities | 4.18 | 0.53 | ||

| Cognitive restructuring and awareness | 4.41 | 0.76 | Playing with natural objects | 4.12 | 0.65 | ||

| Expressing stress | 4.18 | 0.65 | Insect-mediated activities | 3.47 | 0.18 | ||

| Identifying and planning solutions | 4.29 | 0.65 | Animal-assisted activities | 3.59 | 0.06 | ||

| Implementing and evaluating solutions | 4.29 | 0.65 | Activity wrap-up and real-life linkage activities | Wrapping up an activity | 4.59 | 0.76 | |

| Assigning tasks | 4.24 | 0.41 |

| Activity Type | Diagnostic Question | Mean | CVR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensory stimulation and mind–body relaxation activities | Is there a need for activities that focus the patient’s attention on the senses and stabilize the body and mind? | 4.35 | 0.76 |

| Self-understanding and problem-solving activities | Is there a need for activities that help the patient develop an integrated self-understanding and problem-solving skills? | 4.53 | 0.88 |

| Social skills and relationship-building activities | Is there a need for activities that enhance social skills for forming and improving relationships with others? | 4.29 | 0.76 |

| Physical activity and exercise | Is there a need for activities that enable the patient to feel physical vitality? | 4.59 | 1.00 |

| Arts and creative activities | Is there a need for arts and creative activities that allow the patient to express themselves freely? | 4.12 | 0.65 |

| Nature-based activities | Is there a need for activities that explore and utilize elements of nature? | 4.18 | 0.65 |

| Activity wrap-up and real-life linkage activities | Is there a need for activities that support practice in daily life to sustain program effects? | 4.29 | 0.65 |

| Expert Opinions on Precautions for Composing and Implementing Programs |

|---|

|

| Item | Expert Comments |

|---|---|

| Type appropriateness |

|

| Activity appropriateness |

|

| Appropriateness of selection questions for activity types |

|

| Item | Changes |

|---|---|

| Activity types |

|

| Sub-activities |

|

| Selection questions for activity types |

|

| Type | Sub-Activity | Mean | CVR | Type | Sub-Activity | Mean | CVR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-understanding and problem-solving activities | Discovering my values | 4.24 | 0.76 | Play activities | Play | 3.94 | 0.41 |

| Noticing emotions | 4.65 | 0.88 | Play with natural objects | 4.12 | 0.65 | ||

| Expressing emotions | 4.24 | 0.65 | Physical activity and exercise | Exercise | 4.29 | 0.53 | |

| Setting my dreams and goals | 3.88 | 0.29 | Yoga | 4.00 | 0.53 | ||

| Self-exploration activities | 4.29 | 0.65 | Forest exercise | 4.59 | 0.88 | ||

| Noticing thoughts | 4.53 | 0.88 | Forest walking | 4.76 | 0.88 | ||

| Noticing the present | 4.18 | 0.65 | Arts and creative activities | Art activities | 4.35 | 0.65 | |

| Finding happiness | 3.94 | 0.53 | Literature activities | 4.12 | 0.29 | ||

| Identifying strengths and weaknesses | 3.76 | 0.29 | Forest literature activities | 3.59 | −0.06 | ||

| Noticing stress | 4.59 | 1.00 | Music activities | 4.12 | 0.41 | ||

| Expressing stress | 4.24 | 0.65 | Laughter activities | 3.82 | 0.06 | ||

| Finding ways to cope and manage stress | 4.18 | 0.65 | Cooking activities | 4.06 | 0.29 | ||

| Cognitive restructuring and awareness | 3.94 | 0.18 | Storytelling | 4.12 | 0.41 | ||

| Problem analysis | 4.06 | 0.53 | Activities mediated by natural elements | Forest experience | 4.53 | 0.76 | |

| Identifying and planning solutions | 4.12 | 0.29 | Indoor plant-use activities | 4.00 | 0.53 | ||

| Implementing and evaluating solutions | 3.94 | 0.18 | Outdoor plant-use activities | 4.47 | 0.76 | ||

| Enhancing social skills | 4.12 | 0.53 | Hydrotherapy activities | 4.29 | 0.65 | ||

| Introductory-stage activities | Ice-breaking | 4.35 | 0.76 | Activity wrap-up and real-life linkage activities | Concluding activities | 4.65 | 0.88 |

| Self-introduction | 4.47 | 0.88 | Assigning practice tasks | 4.00 | 0.41 | ||

| Setting rules | 4.35 | 0.76 | |||||

| Sensory stimulation and mind-body relaxation activities | Meditation | 4.65 | 0.88 | ||||

| Breathing Techniques | 4.47 | 0.88 | |||||

| Physical relaxation | 4.76 | 1.00 | |||||

| Stretching | 4.59 | 1.00 | |||||

| Tea ceremony | 4.00 | 0.41 | |||||

| Awakening the five senses | 4.41 | 0.76 | |||||

| Activity Type | Mean | CVR |

|---|---|---|

| Introductory-stage activities | 3.94 | 0.41 |

| Activity wrap-up and real-life linkage activities | 4.12 | 0.65 |

| Activity Type | Diagnostic Question | Mean | CVR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensory stimulation and mind–body relaxation activities | Is there a need for activities that focus the patient’s attention on the senses and stabilize the body and mind? | 4.65 | 1.00 |

| Self-understanding and problem-solving activities | Is there a need for activities that help the patient understand themselves and others and develop problem-solving skills? | 4.18 | 0.65 |

| Play activities | Is there a need for activities that allow the patient to actively release tension and experience enjoyment? | 4.29 | 0.77 |

| Physical activity and exercise | Is there a need for activities that enable the patient to feel physical vitality? | 4.41 | 0.88 |

| Arts and creative activities | Is there a need for arts and creative activities that allow the patient to express themselves freely? | 4.29 | 0.77 |

| Activities mediated by natural elements | Is there a need for activities that explore and use elements of nature? | 4.41 | 0.65 |

| Activity wrap-up and real-life linkage activities | Is there a need for activities that help patients practice in daily life to sustain the program’s benefits? | 4.35 | 0.77 |

| No. | Precaution Content | Mean | CVR |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | The patient may be at risk of allergic reactions during forest activities. (Type of allergy: ________) | 4.65 | 0.88 |

| 2 | The patient has uncomfortable body areas or medical conditions that make certain activities impossible. (Specify: ________) | 4.76 | 1.00 |

| 3 | The patient feels discomfort when sensory stimulation becomes excessive. | 4.18 | 0.65 |

| 4 | The patient feels uncomfortable with physical contact with others. | 4.47 | 0.88 |

| 5 | The patient has fears related to specific persons (e.g., gender, age). (Characteristics of the person: ________) | 4.12 | 0.65 |

| 6 | The patient fears cues that may evoke particular events or memories. (Matters to be avoided: ________) | 4.24 | 0.65 |

| 7 | The patient feels anxiety when engaging in activities that deeply explore their inner self. | 3.88 | 0.41 |

| 8 | The patient feels burdened expressing thoughts and emotions in front of others. | 4.25 | 0.65 |

| 9 | The patient feels uncomfortable engaging in activities in open spaces where they feel observed by others. | 4.00 | 0.65 |

| 10 | The patient feels anxiety in specific places (e.g., near bodies of water, dark spaces, enclosed spaces). (Specify: ________) | 4.35 | 0.88 |

| Item | Expert Comments |

|---|---|

| Type appropriateness |

|

| Activity appropriateness |

|

| Appropriateness of selection questions for activity types |

|

| Importance of precautions |

|

| Item | Changes |

|---|---|

| Activity types |

|

| Sub-activities |

|

| Selection questions for activity types |

|

| Precautions |

|

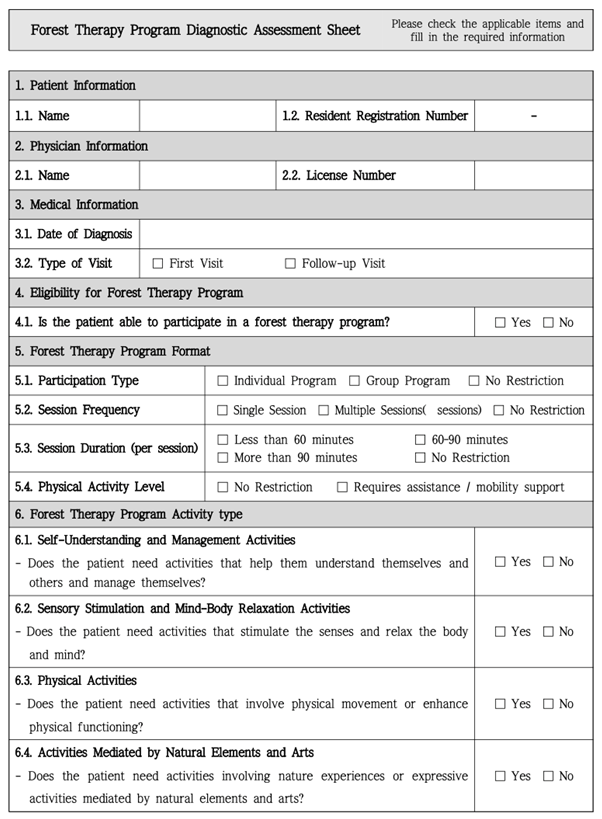

| Activity Type | Content (Selection Questions and Therapy Activities) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Purpose-Based Activities | Self-Understanding and Management Activities | Selection Question: Does the patient need activities that help them understand themselves and others and manage themselves? | ☐Yes ☐No |

| • Self-exploration activities • Emotion-exploration activities • Thought-awareness activities • Present-moment awareness activities • Happiness-exploration activities • Problem-analysis activities • Stress-management activities • Social-skills enhancement activities | |||

| Utilization-Based Activities | Introductory-Stage Activities (Essential Components) | No selection question (mandatory program components) | |

| • Self-introduction • Ice-breaking • Setting rules | |||

| Sensory Stimulation and Mind–Body Relaxation Activities | Selection Question: Does the patient need activities that stimulate the senses and relax the body and mind? | ☐Yes ☐No | |

| • Awakening the five senses • Stretching • Physical relaxation activities • Breathing techniques • Meditation | |||

| Physical Activities | Selection Question: Does the patient need activities that involve physical movement or enhance physical functioning? | ☐Yes ☐No | |

| • Forest walking • Physical-function enhancement exercise • Yoga | |||

| Activities Mediated by Natural Elements and Arts | Selection Question: Does the patient need activities involving nature experiences or expressive activities mediated by natural elements and arts? | ☐Yes ☐No | |

| • Forest experience • Water-use activities • Play with natural objects • Indoor plant-care activities • Outdoor plant-care activities • Art activities | |||

| Closing-Stage Activities (Essential Components) | No selection question (mandatory program components) | ||

| • Closing activities | |||

| Category | Content | |

|---|---|---|

| Physical-condition related Precaution | The patient may be at risk of allergic reactions during forest activities. | ☐Yes ☐No |

| Certain activities may be unsuitable if the patient has discomfort or a medical condition in a specific body area. | ☐Yes ☐No | |

| The patient may feel discomfort if sensory stimulation is excessive or overwhelming. | ☐Yes ☐No | |

| Psychological-condition related Precaution | The patient feels discomfort with physical contact from others. | ☐Yes ☐No |

| The patient experiences fear or discomfort toward specific individuals (e.g., gender, age group). | ☐Yes ☐No | |

| The patient experiences fear regarding situations or activities that evoke certain past events or memories. | ☐Yes ☐No | |

| The patient feels burdened when expressing thoughts or emotions in front of others. | ☐Yes ☐No | |

| Location-related Precaution | The patient feels discomfort engaging in activities conducted in enclosed spaces perceived as confining. | ☐Yes ☐No |

| The patient feels anxiety in certain locations (e.g., near water, dark spaces, narrow spaces, or enclosed areas). | ☐Yes ☐No | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kim, G.; Kang, S.; Paek, K.; Seo, Y.; Choi, H.; Park, S.; Yeon, P. Composition of Diagnostic Assessment Sheet Items for Developing a Personalized Forest Therapy Program for Patients with Depression: Application of the Delphi Technique. Healthcare 2026, 14, 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010116

Kim G, Kang S, Paek K, Seo Y, Choi H, Park S, Yeon P. Composition of Diagnostic Assessment Sheet Items for Developing a Personalized Forest Therapy Program for Patients with Depression: Application of the Delphi Technique. Healthcare. 2026; 14(1):116. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010116

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Gayeon, Sinae Kang, Kyungsook Paek, Youngeun Seo, Hyoju Choi, Seyeon Park, and Pyeongsik Yeon. 2026. "Composition of Diagnostic Assessment Sheet Items for Developing a Personalized Forest Therapy Program for Patients with Depression: Application of the Delphi Technique" Healthcare 14, no. 1: 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010116

APA StyleKim, G., Kang, S., Paek, K., Seo, Y., Choi, H., Park, S., & Yeon, P. (2026). Composition of Diagnostic Assessment Sheet Items for Developing a Personalized Forest Therapy Program for Patients with Depression: Application of the Delphi Technique. Healthcare, 14(1), 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010116

_MD__MPH_PhD.png)