Motivations for Use, User Experience and Quality of Reproductive Health Mobile Applications in a Pre-Menopausal User Base: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

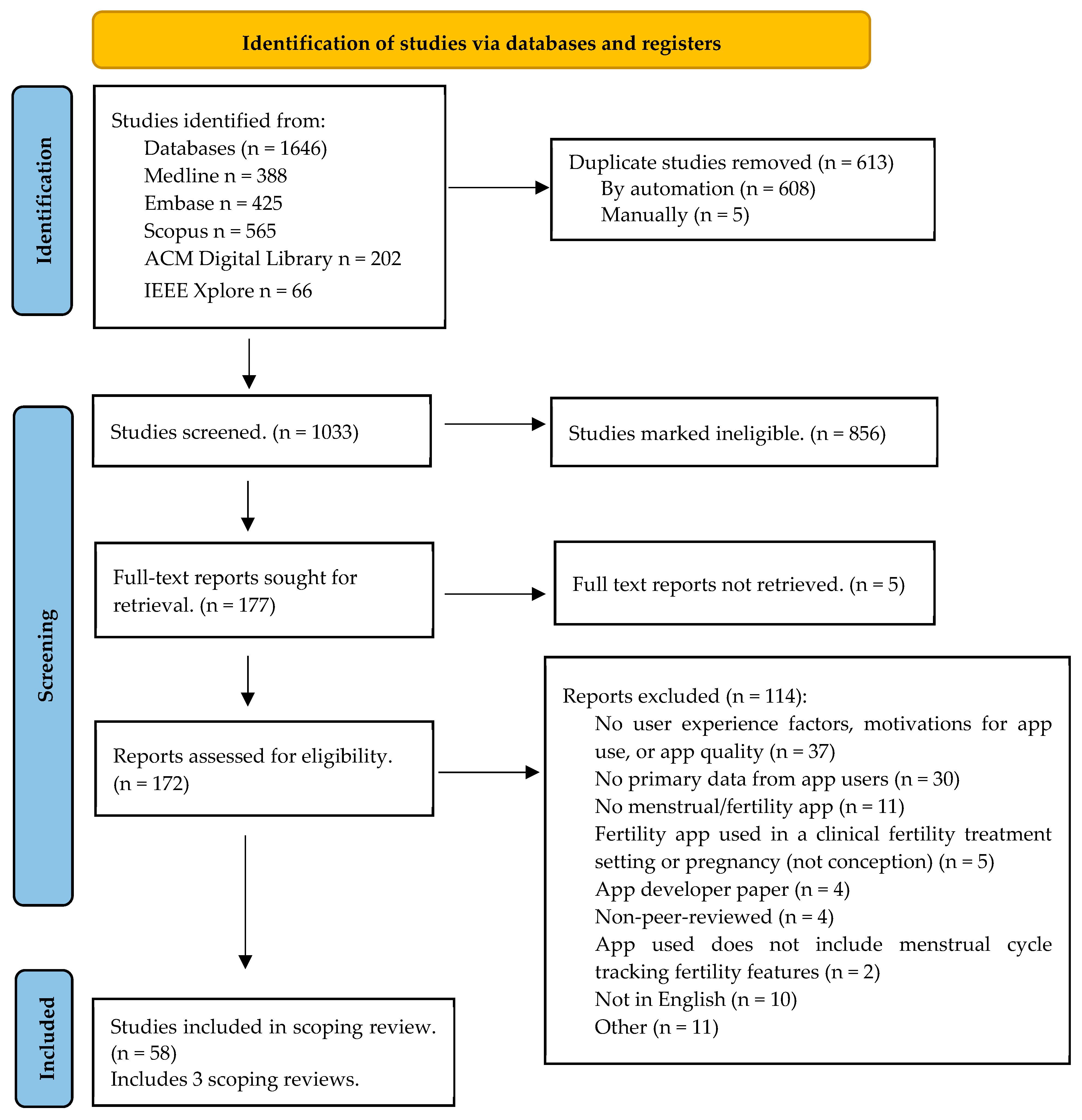

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.1.1. Preliminary Search

2.1.2. Types of Source

2.1.3. Study/Source of Evidence Selection

2.1.4. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.1.5. Charting the Data: Extraction and Presentation

3. Results

3.1. Reproductive Health Apps

Reproductive Health App Recruitment and Demographics

3.2. Themes

3.2.1. Motivations for App Use

Apps as a Non-Hormonal Alternative

3.2.2. User Experience: Strengths

Cycle Management

Educational Tool

3.2.3. User Experience: Limitations

3.3. App Quality and Features

3.3.1. Limited Regulation of Apps

3.3.2. Incorrect Predictions

3.3.3. Design Limitations

4. Discussion

4.1. Motivations for App Use

4.1.1. User Experience: Management, Education, Empowerment

4.1.2. App Limitations

4.1.3. Diversity Issues

4.1.4. Role of Healthcare Professionals

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Database Search Strategy

| # | Searches | Results |

| 1 | Fertility/or Menstrual Cycle/ | 57,848 |

| 2 | (menstru* or “period track*” or fertility).kf,tw. | 158,304 |

| 3 | 1 or 2 | 177,575 |

| 4 | Smartphone/ or Mobile Applications/ | 58,337 |

| 5 | (tracker* or tracking or app or apps).kf,tw. | 156,438 |

| 6 | 4 or 5 | 165,751 |

| 7 | 3 and 6 | 543 |

| 8 | limit 7 to animals | 84 |

| 9 | 7 not 8 | 459 |

| 10 | limit 9 to yr = “2010–Current” | 388 |

| # | Searches | Results |

| 1 | female fertility/or menstrual cycle/ | 53,990 |

| 2 | (menstru* or “period track*” or fertility).kf,tw. | 193,189 |

| 3 | 1 or 2 | 210,381 |

| 4 | mobile phone/or smartphone/or mobile application/ | 60,818 |

| 5 | (tracker* or tracking or app or apps).kf,tw. | 216,193 |

| 6 | 4 or 5 | 259,941 |

| 7 | 3 and 6 | 1106 |

| 8 | limit 7 to embase | 538 |

| 9 | limit 8 to yr = “2010–Current” | 461 |

| 10 | limit 9 to animals | 36 |

| 11 | 9 not 10 | 425 |

- Scopus: searched 25 April 2023(TITLE-ABS-KEY (menstru* OR “period track*” OR fertility) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (tracker* OR tracking OR app OR apps)) AND PUBYEAR > 2009 AND PUBYEAR < 2024 AND (LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE, “ar”) OR LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE, “cp”)) AND (EXCLUDE (EXACTKEYWORD, “animals”))Results: 565ACM Digital Library: searched 25 April 2023AllField:(menstru* or “period track*” or fertility) AND All Field:(tracker* or tracking or app or apps); Applied filters: 2010–2023Results: 1367IEEE Xplore: searched 26 April 2023(“All Metadata”:menstru* OR “All Metadata”:”period tracker” OR “All Metadata”:”period trackers” OR “All Metadata”:”period tracking” OR “All Metadata”:fertility) AND (“All Metadata”:tracker* OR “All Metadata”:tracking OR “All Metadata”:app OR “All Metadata”:apps)Date limit: 2010–2023Results: 66

References

- Market.Us. GlobeNewswire Newsroom. mHealth Market is Projected to Reach USD 187.7 Billion by 2033|Supported by an Impressive CAGR of 11.5%. 2024. Available online: https://www.globenewswire.com/en/news-release/2024/01/24/2815055/0/en/mHealth-Market-is-Projected-to-Reach-USD-187-7-Billion-by-2033-Supported-by-an-Impressive-CAGR-of-11-5.html (accessed on 23 September 2024).

- Pichon, A.; Jackman, K.B.; Winkler, I.T.; Bobel, C.; Elhadad, N. The messiness of the menstruator: Assessing personas and functionalities of menstrual tracking apps. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. JAMIA 2022, 29, 385–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rshoud, F.; Qudsi, A.; Naffa, F.W.; Al Omari, B.; AlFalah, A.G. The Use and Efficacy of Mobile Fertility-tracking Applications as a Method of Contraception: A Survey. Curr. Obstet. Gynecol. Rep. 2021, 10, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnan, T.; Coull, B.A.; Jukic, A.M.; Mahalingaiah, S. The real-world applications of the symptom tracking functionality available to menstrual health tracking apps. Curr. Opin.Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 2021, 28, 574–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eschler, J.; Menking, A.; Fox, S.; Backonja, U. Defining Menstrual Literacy With the Aim of Evaluating Mobile Menstrual Tracking Applications. Comput. Inform. Nurs. CIN 2019, 37, 638–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epstein, D.A.; Lee, N.B.; Kang, J.H.; Agapie, E.; Schroeder, J.; Pina, L.R.; Fogarty, J.; Kientz, J.A.; Munson, S. Examining Menstrual Tracking to Inform the Design of Personal Informatics Tools. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems CHI Conference, Denver, CO, USA, 6–11 May 2017; Volume 2017, pp. 6876–6888. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, J.; Romo-Aviles, N. “A good little tool to get to know yourself a bit better”: A qualitative study on users’ experiences of app-supported menstrual tracking in Europe. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karasneh, R.A.; Al-Azzam, S.I.; Alzoubi, K.H.; Muflih, S.M.; Hawamdeh, S.S. Smartphone Applications for Period Tracking: Rating and Behavioral Change among Women Users. Obstet. Gynecol. Int. 2020, 2020, 2192387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncalves, A.S.S.; Prado, D.S.; Silva, L.M. Frequency and experience in the use of menstrual cycle monitoring applications by Brazilian women. Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care 2021, 26, 291–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Druce, K.L.; Dixon, W.G.; McBeth, J. Maximizing Engagement in Mobile Health Studies. Rheum. Dis. Clin. North Am. 2019, 45, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schantz, J.S.; Fernandez, C.S.P.; Anne Marie, Z.J. Menstrual Cycle Tracking Applications and the Potential for Epidemiological Research: A Comprehensive Review of the Literature. Curr. Epidemiol. Rep. 2021, 8, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.; Torous, J. The Potential of Object-Relations Theory for Improving Engagement With Health Apps. JAMA 2019, 322, 2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalampalikis, A.; Chatziioannou, S.S.; Protopapas, A.; Gerakini, A.M.; Michala, L. mHealth and its application in menstrual related issues: A systematic review. Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care 2022, 27, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zwingerman, R.; Chaikof, M.; Jones, C. A Critical Appraisal of Fertility and Menstrual Tracking Apps for the iPhone. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. JOGC 2020, 42, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broad, A.; Biswakarma, R.; Harper, J.C. A survey of women’s experiences of using period tracker applications: Attitudes, ovulation prediction and how the accuracy of the app in predicting period start dates affects their feelings and behaviours. Women’s Health 2022, 18, 17455057221095246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, S.; Lee, J.; An, D.; Woo, H. Menstrual Tracking Mobile App Review by Consumers and Health Care Providers: Quality Evaluations Study. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2023, 11, e40921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Munn, Z.; Tricco, A.C.; Khalil, H.; Munn, Z. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2020; pp. 406–451. [Google Scholar]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMAScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earle, S.; Marston, H.R.; Hadley, R.; Banks, D. Use of menstruation and fertility app trackers: A scoping review of the evidence. BMJ Sex. Reprod. Health 2021, 47, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvergne, A.; Vlajic Wheeler, M.; Hogqvist Tabor, V. Do sexually transmitted infections exacerbate negative premenstrual symptoms? Insights from digital health. Evol. Med. Public Health 2018, 2018, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andelsman, V. Materializing. MedieKultur 2021, 37, 54–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, K.; Burford, O.; Emmerton, L. Mobile Health Apps to Facilitate Self-Care: A Qualitative Study of User Experiences. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0156164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglund Scherwitzl, E.; Gemzell Danielsson, K.; Sellberg, J.A.; Scherwitzl, R. Fertility awareness-based mobile application for contraception. Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care 2016, 21, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blair, D.L.; Morgan, H.M.; McLernon, D.J. Women’s perspectives on smartphone apps for fertility tracking and predicting conception: A mixed methods study. Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care 2021, 26, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradley, D.; Landau, E.; Jesani, N.; Mowry, B.; Chui, K.; Baron, A.; Wolfberg, A. Time to conception and the menstrual cycle: An observational study of fertility app users who conceived. Hum. Fertil. 2021, 24, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bull, J.; Rowland, S.; Lundberg, O.; Berglund-Scherwitzl, E.; Gemzell-Danielsson, K.; Trussell, J.; Scherwitzl, R. Typical use effectiveness of Natural Cycles: Postmarket surveillance study investigating the impact of previous contraceptive choice on the risk of unintended pregnancy. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e026474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa Figueiredo, M.; Huynh, T.; Takei, A.; Epstein, D.A.; Chen, Y. Goals, life events, and transitions: Examining fertility apps for holistic health tracking. JAMIA Open 2021, 4, ooab013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Cunha Pereira, P.; Monteiro, I.; Bahamondes, L. Natural contraception apps knowledge among Brazilian women and Obstetrics and Gynaecology residents. Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care 2022, 27, 289–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietrich, J.E.; Yee, D.L.; Santos, X.M.; Bercaw-Pratt, J.L.; Kurkowski, J.; Soni, H.; Lee-Kim, Y.J.; Shah, M.D.; Mahoney, D.; Srivaths, L.V. Assessment of an Electronic Intervention in Young Women with Heavy Menstrual Bleeding. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2017, 30, 243–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudouet, L. Digitised fertility: The use of fertility awareness apps as a form of contraception in the United Kingdom. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2022, 5, 100261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, M.C.; Caldeira, C.; Eikey, E.; Mazmanian, M.; Chen, Y. Engaging with health data: The interplay between self-tracking activities and emotions in fertility struggles. In Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 12–13 December 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, E.A.; Roman, S.D.; McLaughlin, E.A.; Beckett, E.L.; Sutherland, J.M. The association between reproductive health smartphone applications and fertility knowledge of Australian women. BMC Women’s Health 2020, 20, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, E.A.; Peters, A.E.; Roman, S.D.; McLaughlin, E.A.; Beckett, E.L.; Sutherland, J.M. A scoping review of the information provided by fertility smartphone applications. Hum. Fertil. 2022, 25, 625–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, S.E.; Menking, A.; Eschler, J.; Backonja, U. Multiples over models: Interrogating the past and collectively reimagining the future of menstrual sensemaking. ACM Trans. Comput.-Hum. Interact. 2020, 27, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, R.S.; Shawe, J.; Tilouche, N.; Earle, S.; Grenfell, P. (Not) talking about fertility: The role of digital technologies and health services in helping plan pregnancy. A qualitative study. BMJ Sex. Reprod. Health 2022, 48, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambier-Ross, K.; McLernon, D.J.; Morgan, H.M. A mixed methods exploratory study of women’s relationships with and uses of fertility tracking apps. Digit. Health 2018, 4, 2055207618785077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gazibara, T.; Cakic, J.; Cakic, M.; Grgurevic, A.; Pekmezovic, T. High School Girls and Smartphone Applications to Track Menstrual Cycle. Cent. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2020, 16, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grenfell, P.; Tilouche, N.; Shawe, J.; French, R.S. Fertility and digital technology: Narratives of using smartphone app “Natural Cycles” while trying to conceive. Sociol. Health Illn. 2021, 43, 116–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haile, L.T.; Fultz, H.M.; Simmons, R.G.; Shelus, V. Market-testing a smartphone application for family planning: Assessing potential of the CycleBeads app in seven countries through digital monitoring. mHealth 2018, 4, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamper, J. ‘Catching Ovulation’: Exploring Women’s Use of Fertility Tracking Apps as a Reproductive Technology. Body Soc. 2020, 26, 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohmann-Marriott, B. Periods as powerful data: User understandings of menstrual app data and information. New Media Soc. 2021, 25, 3028–3046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohmann-Marriott, B.; Starling, L. “What if it’s wrong?” Ovulation and fertility understanding of menstrual app users. In SSM—Qualitative Research in Health; University of Otago: Dunedin, New Zealand, 2022; Volume 2, p. 100057. [Google Scholar]

- Hohmann-Marriott, B.E.; Williams, T.A.; Girling, J.E. The role of menstrual apps in healthcare: Provider and patient perspectives. N. Z. Med. J. 2023, 136, 42–53. [Google Scholar]

- Homewood, S.; Karlsson, A.; Vallgårda, A. Removal as a Method: A fourth wave HCI approach to understanding the experience of self-tracking. In Proceedings of the 2020 ACM Designing Interactive Systems Conference, Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 6–10 July 2020; pp. 1779–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, A.E.; Vesely, S.K.; Haamid, F.; Christian-Rancy, M.; O’Brien, S.H. Mobile Application vs Paper Pictorial Blood Assessment Chart to Track Menses in Young Women: A Randomized Cross-over Design. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2018, 31, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josephy, T.; Sanan, S.; Thayer, E.; Godfrey, E. Comparison of Paper Diaries, Text Messages and Smartphone App to Track Bleeding and Other Symptoms for Contraceptive Studies. Matern. Child Health J. 2022, 26, 1211–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jukic, A.M.Z.; Jahnke, H.R.; MacNell, N.; Bradley, D.; Malloy, S.M.; Baird, D.D. Feasibility of leveraging menstrual cycle tracking apps for preconception research recruitment. Front. Reprod. Health 2022, 4, 981878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Kim, J. Can menstrual health apps selected based on users’ needs change health-related factors? A double-blind randomized controlled trial. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. JAMIA 2019, 26, 655–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lee, M.A. Validation and usability study of the framework for a user needs-centered mHealth app selection. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2022, 167, 104877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemoine, M.E.; O’Connell, S.B.L.; Grunberg, P.H.; Gagne, K.; Ells, C.; Zelkowitz, P. Information needs of people seeking fertility services in Canada: A mixed methods analysis. Health Psychol. Behav. Med. 2021, 9, 104–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, J. “It’s your period and therefore it has to be pink, and you are a girl”: Users’ experiences of (de-)gendered menstrual app design. In Proceedings of the 4th Conference on Gender & IT—GenderIT ’18, Heilbronn, Germany, 14–15 May 2018; ACM Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 63–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKrill, K.; Groom, K.M.; Petrie, K.J. The effect of symptom-tracking apps on symptom reporting. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2020, 25, 1074–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, A.; Padmakumar, K.; Krishna, S.R. Menstrual Tracking Apps in India: User Perceptions, Attitudes, and Implications. Indian J. Mark. 2023, 53, 8–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özçelik, E.; Uzuner, A.; Karahan, O.; Atıcı, E.; Özendi, Y. Standard days method: Comparison of CycleBeads and Smartphone app. Int. Med. 2020, 2, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponzo, S.; Wickham, A.; Bamford, R.; Radovic, T.; Zhaunova, L.; Peven, K.; Klepchukova, A.; Payne, J.L. Menstrual cycle-associated symptoms and workplace productivity in US employees: A cross-sectional survey of users of the Flo mobile phone app. Digit. Health 2022, 8, 20552076221145852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richman, A.R.; Webb, M.C.; Brinkley, J.; Martin, R.J. Sexual behaviour and interest in using a sexual health mobile app to help improve and manage college students’ sexual health. Sex Educ. 2014, 14, 310–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, S.; Paskova, K. A post-phenomenological analysis of using menstruation tracking apps for the management of premenstrual syndrome. Digit. Health 2022, 8, 20552076221144199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, I.; Ogundiran, O.; Cheong, Y. Digital support tools for fertility patients—A narrative systematic review. Hum. Fertil. 2021, 26, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shelus, V.; Ashcroft, N.; Burgess, S.; Giuffrida, M.; Jennings, V. Preventing Pregnancy in Kenya Through Distribution and Use of the CycleBeads Mobile Application. Int. Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health 2017, 43, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, M.; Kanaoka, H. Effectiveness of mobile application for menstrual management of working women in Japan: Randomized controlled trial and medical economic evaluation. J. Med. Econ. 2018, 21, 1131–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparidaens, E.M.; Logger, J.G.M.; Nelen, W.L.D.M.; Braat, D.D.M.; Fleischer, K.; Hermens, R.P.M. Web-based Guidance for Assisted Reproductive Technology With an Online App (myFertiCare): Quantitative Evaluation With the HOT-fit Framework. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e38535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanford, J.B.; Willis, S.K.; Hatch, E.E.; Rothman, K.J.; Wise, L.A. Fecundability in relation to use of mobile computing apps to track the menstrual cycle. Hum. Reprod. 2020, 35, 2245–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starling, M.S.; Kandel, Z.; Haile, L.; Simmons, R.G. User profile and preferences in fertility apps for preventing pregnancy: An exploratory pilot study. mHealth 2018, 4, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symul, L.; Wac, K.; Hillard, P.; Salathe, M. Assessment of menstrual health status and evolution through mobile apps for fertility awareness. NPJ Digit. Med. 2019, 2, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuli, A.; Singh, S.; Narula, R.; Kumar, N.; Singh, P. Rethinking Menstrual Trackers Towards Period-Positive Ecologies. In Proceedings of the 2022 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, New Orleans, LA, USA, 30 April–5 May 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokomizo, R.; Nakamura, A.; Sato, M.; Nasu, R.; Hine, M.; Urayama, K.Y.; Kishi, H.; Sago, H.; Okamoto, A.; Umezawa, A. Smartphone application improves fertility treatment-related literacy in a large-scale virtual randomized controlled trial in Japan. NPJ Digit. Med. 2021, 4, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zampino, L. Self-tracking Technologies and the Menstrual Cycle: Embodiment and Engagement with Lay and Expert Knowledge. Tecnoscienza 2019, 10, 31–52. [Google Scholar]

- Berglund Scherwitzl, E.; Lundberg, O.; Kopp Kallner, H.; Gemzell Danielsson, K.; Trussell, J.; Scherwitzl, R. Perfect-use and typical-use Pearl Index of a contraceptive mobile app. Contraception 2017, 96, 420–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- About Clue. Available online: https://helloclue.com/about-clue (accessed on 23 September 2024).

- Natural Cycles. FAQs|How Much Does Natural Cycles Cost & More. 2020. Available online: https://www.naturalcycles.com/ca/faqs (accessed on 23 September 2024).

- Henrich, J.; Heine, S.J.; Norenzayan, A. The weirdest people in the world? Behav. Brain Sci. 2010, 33, 61–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armour, M.; Hyman, M.S.; Al-Dabbas, M.; Parry, K.; Ferfolja, T.; Curry, C.; MacMillan, F.; Smith, C.A.; Holmes, K. Menstrual Health Literacy and Management Strategies in Young Women in Australia: A National Online Survey of Young Women Aged 13-25 Years. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2021, 34, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, K.; Curry, C.; Sherry; Ferfolja, T.; Parry, K.; Smith, C.; Hyman, M.; Armour, M. Adolescent Menstrual Health Literacy in Low, Middle and High-Income Countries: A Narrative Review. IJERPH 2021, 18, 2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretschneider, R.A. A goal- and context-driven approach in mobile period tracking applications. In International Conference on Universal Access in Human-Computer Interaction; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moglia, M.L.; Nguyen, H.V.; Chyjek, K.; Chen, K.T.; Castaño, P.M. Evaluation of Smartphone Menstrual Cycle Tracking Applications Using an Adapted APPLICATIONS Scoring System. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 127, 1153–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, R.; Gurtin, Z.B.; Harper, J.C. Do fertility tracking applications offer women useful information about their fertile window? Reprod. BioMed. Online 2021, 42, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setton, R.; Tierney, C.; Tsai, T. The Accuracy of Web Sites and Cellular Phone Applications in Predicting the Fertile Window. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 128, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, A.; Watch out, Ladies: Your Period-Tracking APP Could Be Leaking Personal Data. Washington Post. 3 August 2016. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-switch/wp/2016/08/03/how-your-period-tracking-app-could-leak-your-most-intimate-information/ (accessed on 23 September 2024).

- Consumer Reports. Glow Pregnancy App Exposed Women to Privacy Threats, Consumer Reports Finds. 2020. Available online: https://www.consumerreports.org/electronics-computers/mobile-security-software/glow-pregnancy-app-exposed-women-to-privacy-threats-a1100919965/ (accessed on 23 September 2024).

- Research, Z.M.; Zion Market Research. Period Tracker Apps Market Size, Share, Growth, Demand, Trend Analysis 2024–2032. Available online: https://www.zionmarketresearch.com/report/period-tracker-apps-market?trk=article-ssr-frontend-pulse_little-text-block (accessed on 23 September 2024).

- Singh, J.; Sillerud, B.; Singh, A. Artificial intelligence, chatbots and ChatGPT in healthcare—Narrative review of historical evolution, current application, and change management approach to increase adoption. J. Med. Artif. Intell. 2023, 6, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, D. Future of Healthcare with Wearables for mHealth Apps. Appinventiv. 2017. Available online: https://appinventiv.com/blog/wearable-technology-in-healthcare/ (accessed on 23 September 2024).

- Kang, H.S.; Exworthy, M. Wearing the Future—Wearables to Empower Users to Take Greater Responsibility for Their Health and Care: Scoping Review. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2022, 10, e35684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahni, N.; Stein, G.; Zemmel, R.; Cutler, D.M. The Potential Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Healthcare Spending; Working Paper Series; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023; Available online: https://www.nber.org/papers/w30857 (accessed on 23 September 2024).

- WHO. Statement on Menstrual Health and Rights. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/22-06-2022-who-statement-on-menstrual-health-and-rights (accessed on 23 September 2024).

- Business of Apps. Flo Revenue and Usage Statistics. 2024. Available online: https://www.businessofapps.com/data/flo-statistics/ (accessed on 23 September 2024).

- Wise, L.A.; Rothman, K.J.; Mikkelsen, E.M.; Stanford, J.B.; Wesselink, A.K.; McKinnon, C.; Gruschow, S.M.; Horgan, C.E.; Wiley, A.S.; Hahn, K.A.; et al. Design and Conduct of an Internet-Based Preconception Cohort Study in North America: Pregnancy Study Online. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 2015, 29, 360–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B.C. Supreme Court Certifies Class Action for Period Tracker app|Vancouver Sun. Available online: https://vancouversun.com/news/local-news/b-c-supreme-court-certifies-class-action-lawsuit-for-period-tracker-app-with-a-million-canadian-users (accessed on 23 September 2024).

- Lupton, D. Quantified sex: A critical analysis of sexual and reproductive self-tracking using apps. Cult. Health Sex. 2015, 17, 440–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tylstedt, B.; Normark, M.; Eklund, L. Reimagining the cycle: Interaction in self-tracking period apps and menstrual empowerment. Front. Comput. Sci. 2023, 5, 1166210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|

| Menstrual cycle and fertility tracking apps | App developer paper |

| Menstruating pre-menopausal females | Does not include primary data from app users |

| Fertility app used in a clinical fertility treatment setting or pregnancy (not conception) | |

| Menopausal population or app | |

| No mention of user experience factors, motivations for app use, or app quality | |

| App used does not include menstrual cycle tracking/fertility features | |

| No menstrual/fertility app | |

| Non-peer-reviewed (i.e., conference proceedings other than computing conferences) | |

| Not in English | |

| Older than 2010 | |

| Other |

| Author (Year) | Country | Study Aims | App/Tech |

|---|---|---|---|

| Al-Rshoud (2021) [3] | Jordan | Examined the efficacy of fertility tracking mobile apps as a natural method of contraception. | Unspecified Fertility Awareness Method (FAM) Apps/Fertility Tracking Mobile Applications |

| Alvergne (2018) [21] | US, UK, Canada, Australia | Explored whether STIs lead to side effects in the days preceding menstruation and assessed digital health research capacity. | Clue |

| Andelsman (2021) [22] | Denmark, Netherlands | Investigated how menstrual cycles materialized within the contextual use of app-assisted period tracking. | Clue, My Calendar, Monthly Cycles, Period Tracker, Flo, Natural Cycles, FitrWoman |

| Anderson (2016) [23] | Australia | Conducted a qualitative analysis of users’ experiences with mobile health apps, their perceived advantages, and proposed recommendations for app enhancements. | Menstrual cycle monitoring (4 types, unspecified) |

| Berglund Scherwitzl (2016) [24] | Sweden | Presented a mobile application (Natural Cycles), outlined its core features and functions, and evaluated its contraceptive effectiveness. | Natural Cycles |

| Berglund Scherwitzl (2017) [23] | Sweden | Calculated the application’s perfect-use efficacy to re-examine its typical-use efficacy and failure rate method. | Natural Cycles |

| Blair (2021) [25] | UK | Investigated women’s use of FTA, their understanding of conception, and the demand for and acceptability of a potential natural conception prediction app. | Ovia Fertility, Glow, Flo, Maya, Ava |

| Bradley (2021) [26] | USA | Assessed the relationship between cycle length and variability and the time to conception using a mobile app. | Ovia Fertility |

| Broad (2022) [15] | UK | Described women’s real-life experiences with period tracker apps, their perceptions of the app and its ovulation information, and how the app’s accuracy in predicting period start dates influenced their feelings and behaviors. | Unspecified Period Tracker Apps |

| Bull (2019) [27] | Sweden | Examined the link between prior contraceptive choices and the app’s effectiveness, as well as the population-level effect of Natural Cycles on unintended pregnancy rates. | Natural Cycles |

| Costa Figueiredo (2021) [28] | USA | Examined the design of consumer-facing fertility apps to understand how they assisted menstruating individuals in achieving diverse fertility-related goals. | A total of 16 apps from Apple and 15 from Google |

| da Cunha Pereira (2022) [29] | Brazil | Evaluated the knowledge and interest of two groups—women and OBGYN residents—regarding natural contraception and smartphone applications. | Unspecified fertility awareness method smartphone apps |

| Dietrich (2017) [30] | USA | A digital strategy was implemented to improve patient adherence to medications and appointments while delivering educational outreach to individuals with heavy menstrual bleeding and bleeding disorders. | iPeriod application |

| Dudouet (2021) [31] | UK | Aimed to investigate personal experiences with using an app for contraception. | Natural Cycles, Kindara, Glow, Clue and Flow. |

| Earle * (2021) [19] | UK | Examined existing knowledge of the use of menstruation and fertility tracking apps. | Menstruation and fertility app trackers |

| Epstein (2017) [6] | USA | Provided insights into why and how women track their menstrual cycles, highlighted design challenges and concerns in digital tools, and offered guidance while challenging assumptions in the design of personal informatics tools. | Selected the 12 most reviewed apps. |

| Figueiredo (2018) [32] | USA | Explored self-tracking and emotions related to fertility, highlighting its highly personalized nature and the complexity of this health concern with limited personal control. | Fertility tracking apps |

| Ford (2020) [33] | Australia | Identified differences in fertility knowledge associated with the use of female reproductive health apps. | Reproductive health apps |

| Ford (2022) [34] | Australia | Reviewed peer-reviewed literature on fertility-based reproductive health apps and examined the information the apps provide. | Fertility apps |

| Fox (2020) [35] | USA | Explored efforts to revisit and reimagine menstrual tracking technology, focusing on mobile apps designed to document and quantify menstrual cycle data. | Period tracking technology/mobile applications |

| French (2022) [36] | UK | Investigated how women and their partners navigate (pre)conception healthcare and the role of Natural Cycles fertility awareness technology in this process. | Natural Cycles |

| Gambier-Ross (2018) [37] | UK (Scotland) | Examined women’s use of and interactions with FTAs to inform the design and development of the next generation of these tools. | Fertility Tracking Apps (FTA) Clue was most popular (12%) |

| Gazibara (2020) [38] | Serbia | Investigated the prevalence of menstrual cycle tracking app use among high school girls and identified factors associated with their usage. | Menstrual cycle tracking apps |

| Goncalves (2021) [9] | Brazil | Assessed the frequency and experiences of app usage among Brazilian women. | The most used apps were Flo (31.1%), My Calendar (25.8%) and Clue (24.9%). |

| Grenfell (2021) [39] | UK | Investigated the role of Natural Cycles in users’ and their partners’ (pre-)conception practices and experiences. | Natural Cycles |

| Haile (2018) [40] | African countries, India, Jordan | Conducted market tests of the CycleBeads app across seven countries. | CycleBeads app |

| Hamper (2020) [41] | UK | Examined women’s use of fertility apps during attempts to conceive and investigated how technological practices influence the understanding of bodies as reproductive. | Fertility tracking applications/fertility apps |

| Hohmann-Marriott (2021) [42] | New Zealand | Investigated app users’ experiences and perceptions, emphasizing menstrual app data within the contexts of menstrual health and digital health. | Menstrual-cycle-tracking apps: 22 were using general predictive apps and 3 had apps applying Fertility Awareness Based Methods. |

| Hohmann-Marriott (2022) [43] | New Zealand | Examined how app users who are not trying to conceive interpreted and utilized information from menstrual apps. | General purpose menstrual apps. Clue is most popular. Flo, Period Tracker, iHealth, Period Diary, My Calendar, and Eve. FABM apps: Ovagraph, My NFP, and Kindara. |

| Hohmann-Marriott (2023) [44] | New Zealand | Aimed to understand the role of menstrual tracking apps in addressing menstrual disorders and diseases in New Zealand by consulting expert stakeholders, including healthcare providers, app users, and patients. | Flo, Clue, Period Tracker, My Calendar, Period Diary, Balance, Apple Health, Fitbit, Lily, Ava, Daysy, Kindara |

| Homewood (2020) [45] | Denmark | Examined how data continues to influence individuals after they stop self-tracking and explored the ways this information manifests within lived experiences. | Clue |

| Jacobson (2018) [46] | USA | Compared patient satisfaction and compliance between mobile app reporting and paper reporting among menstruating adolescent girls. | PBAC diary in mobile app format |

| Josephy (2022) [47] | USA | Assessed the completeness and timeliness of data gathered through apps, text messages, and paper diaries. | Clue |

| Jukic (2023) [48] | USA | Analyzed the characteristics of users of a menstrual cycle tracking app among participants in an online research study. | Ovia Fertility |

| Karasneh * (2020) [8] | Jordan | Conducted a systematic review to identify period tracking smartphone apps and evaluate their composition, quality, and effectiveness. | 49 available English language and free-to-download apps were included on period tracking |

| Ko (2023) [16] | Korea | Reviewed existing menstrual apps, focusing on their primary content and quality as evaluated by healthcare providers and consumers. | 34 apps identified with the keywords “period” and “menstrual cycle” in English and Korean |

| Lee (2019) [49] | Korea | Investigated whether menstrual health mobile apps can be chosen based on users’ needs to influence health-related factors. | 2 unspecified apps |

| Lee (2022) [50] | Korea, USA | Focused on refining and enhancing MASUN 1.0 while evaluating the feasibility and usability of the updated version, MASUN 2.0. | 5 menstrual apps |

| Lemoine (2021) [51] | Canada | Identified the information needs of individuals seeking fertility services, analyzed the relationships between meeting these needs, psychological outcomes, and demographics, and discussed the implications for readability standards. | Infotility (informational web-based app) |

| Levy (2018) [52] | Austria, Spain | Explored users’ experiences with and reactions to gendered design in app-supported menstrual tracking. | Unspecified menstrual apps |

| Levy (2019) [7] | Austria, Spain, Italy | Investigated how period-tracking apps contribute to user empowerment and enhance menstrual health literacy. | App-supported menstrual tracking |

| MacKrill (2020) [53] | New Zealand | Examined the impact of a menstrual-monitoring app with a symptom tracker on symptom reporting. | Flo, Next Period |

| Nair (2023) [54] | India | Explored young women’s knowledge, attitudes, and practices concerning the use of mobile applications for menstrual tracking. | 42.5% used some kind of health-tracking mobile app. Users of the MTA Flo had the highest representation (30.7%). The sample also had users of the Indian MTAMaya (17.9%) |

| Ozcelik (2020) [55] | Turkey | Compared effectiveness, satisfaction, and continuation rates between the traditional CycleBeads method and its smartphone application counterpart. | CycleBeads App |

| Ponzo (2022) [56] | UK | Assessed the impact of menstrual cycle-related disturbances on work productivity among Flo app users. | Flo Health App |

| Richman (2014) [57] | USA | Evaluated college students’ (1) sexual health behaviors, (2) mobile technology usage, and (3) interest in a mobile health app for improving and managing sexual health. | Not specified |

| Riley (2022) [58] | New Zealand | Aimed to expand the MTA study both empirically and theoretically by analyzing the experiences of five users managing PMS with MTA. | Clue, Flo |

| Robertson (2021) [59] | UK | Reviewed and summarized all digital support tools developed to date for fertility patients. | 46 digital support tools for fertility patients |

| Schantz * (2021) [11] | USA | Reviewed and synthesized literature on MCTAs regarding their applicability in epidemiologic research. | Menstrual Cycle Tracking Apps (MCTA) |

| Shelus (2017) [60] | Kenya | Evaluated whether the app attracted new family planning users, examined user experiences, and analyzed how these experiences differed based on the channel through which women discovered the app. | CycleBeads app |

| Song (2018) [61] | Japan | Examined the effectiveness of a mobile application in mitigating mental and physical disorders and reducing labor productivity loss caused by menstruation-related symptoms among working women in Japan. | Karada-no-kimochi |

| Sparidaens (2023) [62] | Netherlands | Assessed the implementation of the myFertiCare app and its impact on couples’ knowledge of fertility treatment, perceived treatment burden, and experience of patient-centered care. | Online myFertiCare app |

| Stanford (2020) [63] | Canada, USA | Evaluated the use of mobile computing apps to estimate their impact on fecundability within an internet-based volunteer group of couples attempting to conceive. | Clue, Fertility Friend, Flo, Glow, Kindara, My Days, Ovia, Period Tracker |

| Starling (2018) [64] | USA | Identified women using or intending to use fertility apps for pregnancy prevention and examined their preferences and perceptions regarding app usage. | Period Tracker, Fertility Calendar, Fertility Friend, Natural Cycles, Ovia, Ovuline, Glow, Dot, Pink Pad Pro, OvaGraph, Kindara, iCycleBeads, Conceivable, Clue, 2DayMethod, and unnamed others |

| Symul (2019) [65] | 150 countries (mostly Europe and Americas) | Characterized users and their tracking behaviors, providing an overview of the observations logged in the apps, and developed a statistical framework for estimating ovulation time based on self-reported data. | Sympto and Kindara, Methods |

| Tuli (2022) [66] | India | (1) Investigated how individuals at various stages of their menstrual journeys engage in tracking and the factors influencing their choices. (2) Examined how tracking practices evolve during the transition from menarche to menopause, reflecting different life decisions. (3) Explored experiences with and aspirations for digital menstrual trackers. | Digital menstrual trackers |

| Yokomizo (2021) [67] | Japan | Examined the potential of high-quality fertility treatment information to improve fertility treatment literacy within a large Japanese population. | Luna |

| Zampino (2019) [68] | Italy | Investigated how individuals engage with self-tracking technologies, reshaping the interaction between expert and lay knowledge. | Self-tracking technologies, apps to manage menstrual periods |

| Author(s) (Year) | Unique Term |

|---|---|

| Al-Rshoud (2021) [3] |

|

| Andelsman (2021) [22] |

|

| Anderson (2016) [23] |

|

| Berglund Scherwitzl (2016, 2017) [24,69] |

|

| Blair (2021), [25] Gambier-Ross (2018) [37] |

|

| Blair (2021) [25] |

|

| Bradley (2021), [26] Jacobson (2018) [46] |

|

| Broad (2022) [15] |

|

| Costa Figueiredo (2021) [28] |

|

| Dietrich (2017) [30] |

|

| Epstein (2017) [6] |

|

| Figueiredo (2018), [32] Homewood (2020) [45] |

|

| Ford (2020) [33] |

|

| Ford (2022) [34] |

|

| Fox (2020) [35] |

|

| French (2022) [36] |

|

| Gazibara (2020) [38] |

|

| Hamper (2020) [41] |

|

| Hohmann-Marriott (2021), (2022), (2023), [42,43,44] Ko (2023) [16] |

|

| Karasneh (2020) [8] |

|

| Lee (2019) [49] |

|

| Levy (2018) [52] |

|

| Levy (2019) [7] |

|

| MacKrill (2020) [53] |

|

| Ozcelik (2020) [55] |

|

| Richman (2014) [57] |

|

| Riley (2022) [58] |

|

| Robertson (2021) [59] |

|

| Schantz (2021) [11] |

|

| Song (2018) [61] |

|

| Stanford (2020) [63] |

|

| Starling (2018) [64] |

|

| Tuli (2022) [66] |

|

| Zampino (2019) [68] |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kazakoff, A.; Doroshuk, M.L.; Ganshorn, H.; Doyle-Baker, P.K. Motivations for Use, User Experience and Quality of Reproductive Health Mobile Applications in a Pre-Menopausal User Base: A Scoping Review. Healthcare 2025, 13, 877. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13080877

Kazakoff A, Doroshuk ML, Ganshorn H, Doyle-Baker PK. Motivations for Use, User Experience and Quality of Reproductive Health Mobile Applications in a Pre-Menopausal User Base: A Scoping Review. Healthcare. 2025; 13(8):877. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13080877

Chicago/Turabian StyleKazakoff, Alissa, Marissa L. Doroshuk, Heather Ganshorn, and Patricia K. Doyle-Baker. 2025. "Motivations for Use, User Experience and Quality of Reproductive Health Mobile Applications in a Pre-Menopausal User Base: A Scoping Review" Healthcare 13, no. 8: 877. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13080877

APA StyleKazakoff, A., Doroshuk, M. L., Ganshorn, H., & Doyle-Baker, P. K. (2025). Motivations for Use, User Experience and Quality of Reproductive Health Mobile Applications in a Pre-Menopausal User Base: A Scoping Review. Healthcare, 13(8), 877. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13080877