Dental Service Provision and Oral Health Conditions of Children Aged 0–12 Years, Northern Thailand: Transferring of Sub-District Health Promotion Hospitals Policy Era

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Methodology

2.2. Population and Sample

2.3. Research Instruments

2.4. Data Source and Data Collection Process

- -

- Oral health examination (Procedure code: 2330011)/Diagnosis code: Z01.2

- -

- Topical fluoride application (procedure codes: 2377020, 2377021)/diagnosis codes: K02.0 (initial caries) and K03.8 (other specified diseases of the hard tissues of teeth)

- -

- Pit and fissure sealant application on permanent teeth (procedure codes: 2387030, 238703A, 238703B, 238703C, 238703D, 238703E, 238703F, 238703G, 238703H)/diagnosis codes: K02.0 (initial caries) and K02.3 (arrested dental caries)

2.5. Data Analysis

- 1.

- Analysis of dental services and oral health conditions

- 2.

- Comparison of dental services and oral health conditions between transferred and non-transferred SHPHs. Trends were visualized using graphs. Statistical analysis included the Chi-square test and unpaired t-test to identify differences between the groups.

2.6. Research Ethics

3. Results

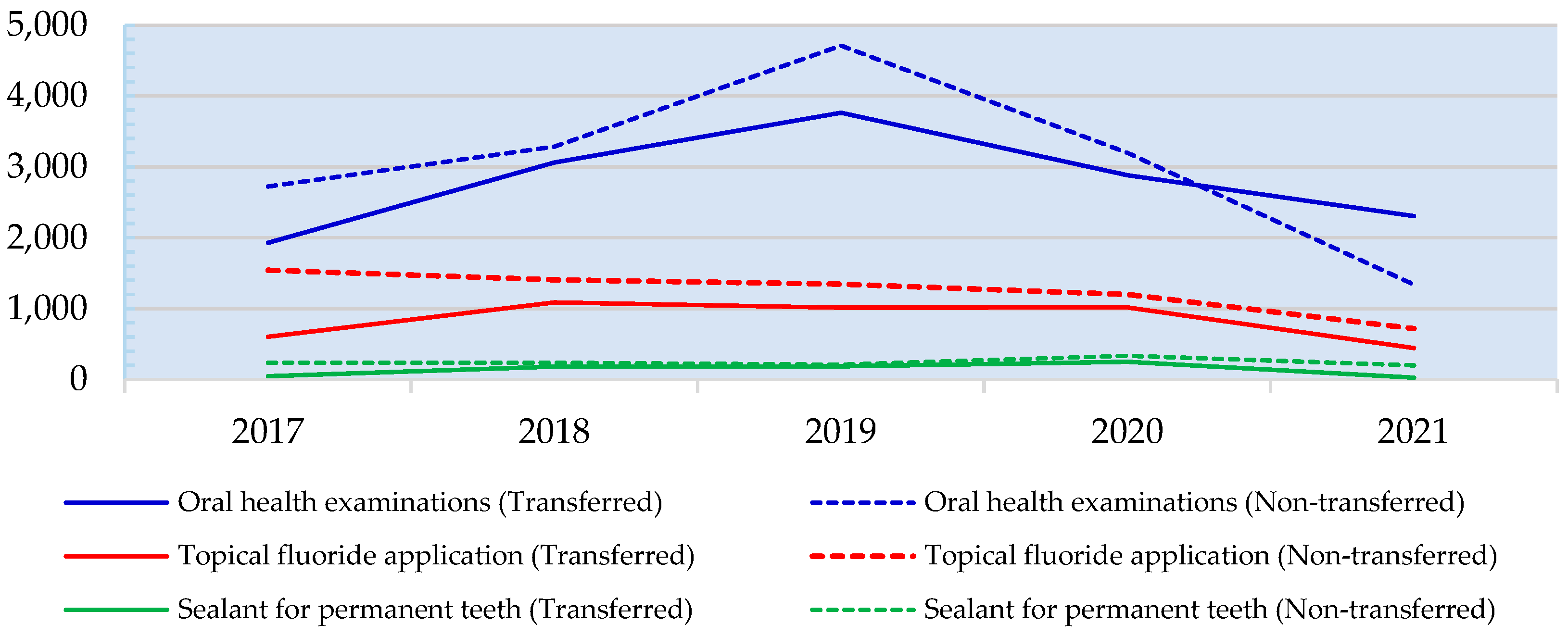

3.1. Comparison of Dental Services for Children Aged 0–12 Years

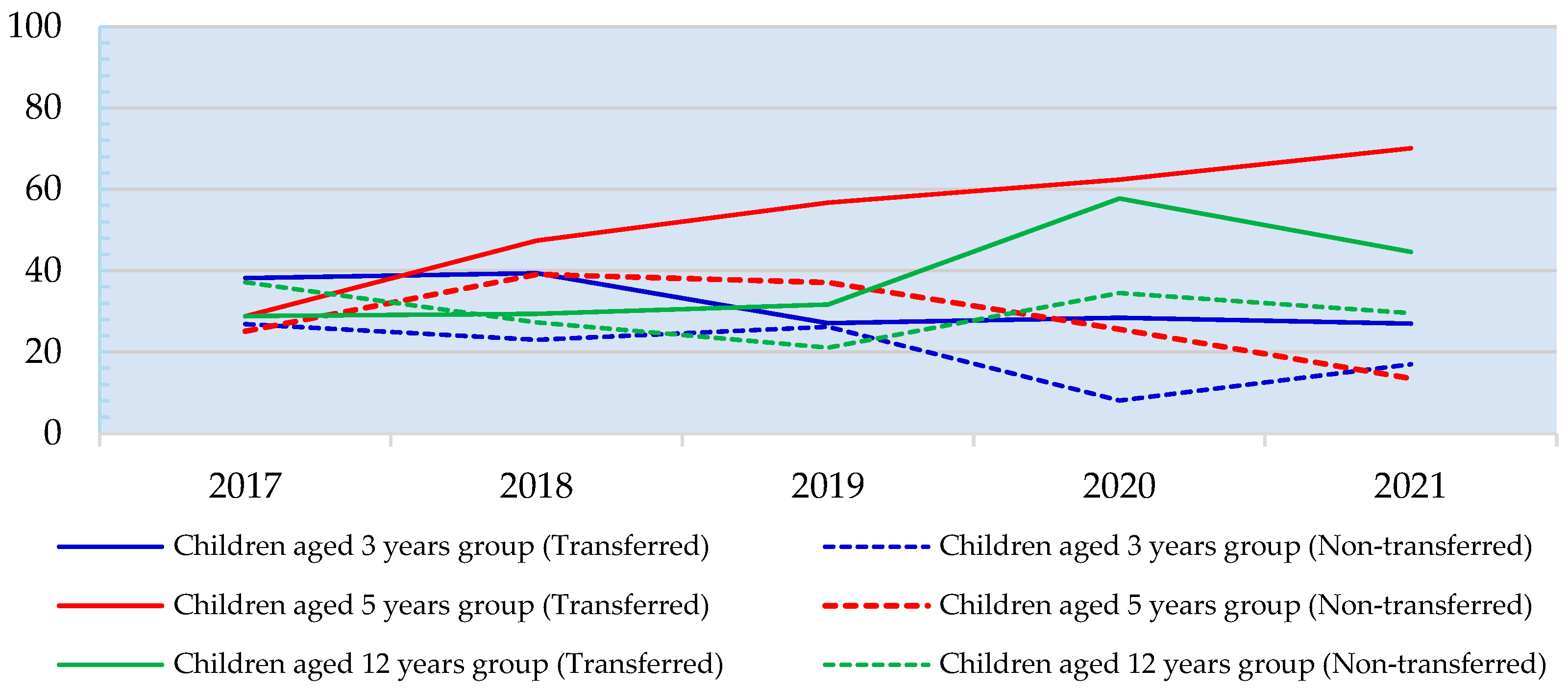

3.2. Comparison of Oral Health Conditions for Children Aged 0–12 Years

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AAPC | Average annual percent change |

| APC | Age-period-cohort |

| ASIR | Age-standardized incidence rate |

| CUP | Contracting unit for primary care |

| EAPC | Estimated annual percent change |

| HPH | Health-promoting hospital |

| IOC | Index of item objective congruence |

| LAO | Local administrative organization |

| MOPH | Ministry of Public Health |

| PAO | Provincial administrative organization |

| PCU | Primary care unit |

| SHPH | Sub-district health promotion hospital |

| STATA | A multicore version of the STATA software |

References

- Office of the Decentralization to the Local Government Organization Committee. Guidelines for Transferring Missions of the Chaloem Phrakiat 60th Anniversary Nawaminthrachini Health Station and Subdistrict Health Promoting Hospital to the Provincial Administrative Organization; The Prime Minister’s Office: Bangkok, Thailand, 2021. (In Thai)

- Primary Health Care System Support Division. Primary Health Care Service Quality Standards Manual 2023; Ministry of Public Health: Nonthaburi, Thailand, 2022.

- Cashin, C.; Ankhbayar, B.; Phuong, H.T.; Jamsran, G.; Nazad, O.; Phuong, N.K. Assessing Health Provider Payment Systems: A Practical Guide for Countries Moving Toward UHC; Joint Learning Network for Universal Health Coverage: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Odoch, W.D.; Senkubuge, F.; Hongoro, C. How has sustainable development goals declaration influenced health financing reforms for universal health coverage at the country level? A scoping review of literature. Glob. Health 2021, 17, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, A.; Kwon, S.; Cowley, P. Health Financing Reforms for Moving towards Universal Health Coverage in the Western Pacific Region. Health Syst. Reform 2019, 5, 32–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Techaatik, S.; Nakham, P. Studying and Monitoring the Development of the Transfer System of Public Health Centers to Local Government Organizations. J. Health Syst. Res. 2009, 3, 113–130. (In Thai) [Google Scholar]

- Srisasalux, J.; Vichathai, C.; Kaewvichian, R. Experience with Health Decentralization: The Health Center Transfer Model. J. Health Syst. Res. 2009, 3, 16–34. (In Thai) [Google Scholar]

- Sri-ngernyuang, L.; Siriwan, P.; Vongjinda, S.; Chuenchom, S. Health Center Devolution: Lesson Learned and Policy Recomendations; Health Systems Research Institute (HSRI): Nonthaburi, Thailand, 2012. (In Thai) [Google Scholar]

- Kulthanmanusorn, A.; Saengruang, N.; Wanwong, Y.; Kosiyaporn, H.; Witthayapipopsakul, W.; Srisasalux, J.; Putthasri, W.; Patcharanarumol, W. Evaluation of the Devolved Health Centers: Synthesis Lesson Learnt from 51 Health Centers and Policy Options; Health Systems Research Institute: Nonthaburi, Thailand, 2018. (In Thai) [Google Scholar]

- Chiangchaisakulthai, K.; Wongsin, U.; Tisayathikom, K.; Suppradist, W.; Samiphuk, N. Unit Cost of Services in Primary Care Cluster. J. Health Syst. Res. 2019, 13, 175–187. (In Thai) [Google Scholar]

- Local Government Promotion Office Uthai Thani Province. Obstacles after transferring missions of the Chaloem Phrakiat 60th Anniversary Nawaminthrachini Health Station and Subdistrict Health Promoting Hospital to the Provincial Administrative Organization. Local Government Promotion Office Uthai Thani Province; 2023. Available online: https://www.uthailocal.go.th/dnm_file/govdoc_stj/153400402_center.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2023).

- Fuengkhajorn, A.; Singweratham, N.; Siewchaisakul, P.; Wungrath, J. Comparison of Access to Dental Services and Oral Health Status among Children Aged 0–12 years between Tumbon Health Promoting Hospital with and without Transferred to the Local Administrative Organization in the Northern Region of Thailand. South. Coll. Netw. J. Nurs. Public Health 2024, 11, e268398. (In Thai) [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health. Report on the Results of the 8th National Oral Health Survey, Thailand 2017; Ministry of Public Health: Nonthaburi, Thailand, 2018.

- Health Data Center. Information to Respond to the Service Plan in the Oral Health; Ministry of Public Health: Nonthaburi, Thailand, 2023.

- Sudhipngpracha, T.; Chotsetakij, W.; Phuripongthanawat, P.; Kittayasophon, U.; Satthatham, N.; Onphothong, Y. Policy Analysis and Policy Design for the Transfer of Sudistrict Health Promotion Hospitals to Provincial Administrative Organizations (PAOs); Health Systems Research Institute (HSRI): Nonthaburi, Thailand, 2021. (In Thai) [Google Scholar]

- Singweratham, N.; Phodah, T.; Techakehakij, W.; Bunpean, A.; Siechaisakul, P.; Nuwsuwan; Siewchaisakul, P.; Sansrisawad, A.; Praesi, S. A comparison of the unit costs of Health care services provided with and without being transferred to the local administrative organization of the Tambon Health Promoting Hospitals. Princes Naradhiwas Univ. J. 2023, 15, 251–264. (In Thai) [Google Scholar]

- The Dental Council of Thailand. Dental Profession Act 1994; The Dental Council of Thailand: Nonthaburi, Thailand, 2021. (In Thai)

- Singweratham, N.; Phodah, T.; Techakehakij, W.; Wongyai, T.; Bunpean, A.; Siechaisakul, P. A Comparison of Budget Allocation of the National Health Security Fund Between the Contraction Unit for Primary Care and the Tambon Health Promoting Hospital with and Without Being Transferred to the Local Administrative Organization for Policy Recommendation; Health Systems Research: Nonthaburi, Thailand, 2023. (In Thai) [Google Scholar]

- Kazeminia, M.; Abdi, A.; Shohaimi, S.; Jalali, R.; Vaisi-Raygani, A.; Salari, N.; Mohammadi, M. Dental caries in primary and permanent teeth in children’s worldwide, 1995 to 2019: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Head Face Med. 2020, 16, 22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Khemwuttipong, A.; Pantumanee, V.; Sangwong, P.; Narin, K. Oral health status of children aged 3–12 years in Trang province: Comparing before, during and after fluoridated milk project in 2014, 2017 and 2020. Thai Dent. Public Health J. 2022, 27, 14–27. [Google Scholar]

| Province | Transfer status | Setting | Size | Population in the Area of Responsibility (People) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kamphaeng Phet | Transferred | SHPH A | S | 2632 |

| Non-transferred | SHPH B | S | 2482 | |

| Chiang Rai | Transferred | SHPH C | M | 3816 |

| Non-transferred | SHPH D | M | 5410 | |

| Chiang Mai | Transferred | SHPH E | M | 6753 |

| Non-transferred | SHPH F | M | 7518 | |

| Tak | Transferred | SHPH G | M | 4545 |

| Non-transferred | SHPH H | M | 4781 | |

| Nan | Transferred | SHPH I | M | 3861 |

| Non-transferred | SHPH J | M | 3842 | |

| Phitsanulok | Transferred | SHPH K | L | 10,146 |

| Non-transferred | SHPH L | L | 13,802 |

| General Context | Status | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transferred SHPH Group (Mean, SD) | Non-Transferred SHPH Group (Mean, SD) | ||

| Distance from network hospital (kilometers) | 10.6 ± 4.7 | 10.1 ± 4.7 | 0.871 # |

| Population in the responsible area (people) | 5320.0 ± 2604.5 | 5320.0 ± 2604.5 | 0.632 # |

| Schools in the responsible area (institutions) | 3.5 ± 1.0 | 3.0 ± 1.1 | 0.438 # |

| Child Development Centers in the responsible area (centers) | 1.3 ± 1.2 | 1.8 ± 1.8 | 0.484 # |

| Positions of Dental Health Personnel (persons) | Number (%) | Number (%) | 1.000 ## |

| Dental Public Health Practitioner | 2 (33.3%) | 1 (16.7%) | |

| Senior Dental Public Health Practitioner | 4 (66.7%) | 4 (66.6%) | |

| Public Health Academic Officer | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (16.7%) | |

| Dental Services | SHPH Status | Number of People Receiving Dental Services by Year (Persons) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | Mean | ||

| Oral health examinations for children aged 0–12 years | Transferred | 1929 | 3061 | 3765 | 2881 | 2306 | 2788.4 |

| Non-transferred | 2722 | 3284 | 4711 | 3197 | 1341 | 3051.0 | |

| Provision of topical fluoride application services for children aged 0-5 years | Transferred | 601 | 1088 | 1014 | 1015 | 446 | 832.8 |

| Non-transferred | 1543 | 1405 | 1346 | 1201 | 720 | 1243.0 | |

| Sealant for permanent teeth for children aged 6 years | Transferred | 46 | 181 | 186 | 252 | 28 | 138.6 |

| Non-transferred | 236 | 235 | 208 | 336 | 199 | 242.8 | |

| Oral Health Conditions by Children Age | SHPH Status | Year | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | Mean | ||

| Prevalence of dental caries (%) | |||||||

| 3 years # | Transferred | 38.2 | 39.4 | 27.1 | 28.4 | 27.0 | 31.3 |

| Non-transferred | 26.9 | 23.0 | 26.2 | 8.1 | 17.0 | 22.2 | |

| 5 years # | Transferred | 28.8 | 47.4 | 56.7 | 62.4 | 70.1 | 51.2 |

| Non-transferred | 25.1 | 39.1 | 37.1 | 25.6 | 13.5 | 30.7 | |

| 12 years ## | Transferred | 28.9 | 29.4 | 31.7 | 57.8 | 44.6 | 37.1 |

| Non-transferred | 37.2 | 27.3 | 21.1 | 34.5 | 29.6 | 30.0 | |

| The average number of decayed, filled, or extracted teeth (teeth per person) | |||||||

| 3 years # | Transferred | 2.1 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.5 | 1.4 |

| Non-transferred | 0.7 | 0.8 | 1.3 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.9 | |

| 5 years # | Transferred | 1.4 | 2.5 | 2.4 | 3.6 | 3.9 | 2.6 |

| Non-transferred | 1.9 | 3.2 | 2.3 | 1.9 | 1.3 | 2.3 | |

| 12 years ## | Transferred | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 1.6 | 1.1 | 1.0 |

| Non-transferred | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 1.1 | 0.4 | 0.7 | |

| Oral Health Conditions | Status | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Transferred Group | Non-Transferred Group | ||

| Prevalence of dental caries | Number (%) | Number (%) | p-Value |

| Children aged 3 years | <0.001 # | ||

| Number of people with detected dental caries | 188 (31.3%) | 187 (22.2%) | |

| Number of people without dental caries | 412 (68.7%) | 655 (77.8%) | |

| Children aged 5 years | <0.001 # | ||

| Number of children with detected dental caries | 283 (51.2%) | 219 (30.7%) | |

| Number of children without dental caries | 270 (48.8%) | 495 (69.3%) | |

| Children aged 12 years | 0.009 # | ||

| Number of children with detected dental caries | 208 (37.1%) | 204 (30.0%) | |

| Number of children without dental caries | 353 (62.9%) | 475 (70.0%) | |

| The average number of decayed, filled, or extracted teeth (teeth per person) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | diffmean ## (95% CI) |

| Children aged 3 years (primary teeth/baby teeth) | 1.4 (2.3) | 0.9 (1.9) | 0.5 (0.3 to 0.7) |

| Children aged 5 years (primary teeth/baby teeth) | 2.6 (2.8) | 2.3 (4.0) | 0.3 (−0.1 to 0.7) |

| Children aged 12 years (permanent teeth/adult teeth) | 1.0 (1.4) | 0.7 (1.5) | 0.3 (0.1 to 0.5) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Singweratham, N.; Fuengkhajorn, A.; Wungrath, J.; Siewchaisakul, P. Dental Service Provision and Oral Health Conditions of Children Aged 0–12 Years, Northern Thailand: Transferring of Sub-District Health Promotion Hospitals Policy Era. Healthcare 2025, 13, 874. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13080874

Singweratham N, Fuengkhajorn A, Wungrath J, Siewchaisakul P. Dental Service Provision and Oral Health Conditions of Children Aged 0–12 Years, Northern Thailand: Transferring of Sub-District Health Promotion Hospitals Policy Era. Healthcare. 2025; 13(8):874. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13080874

Chicago/Turabian StyleSingweratham, Noppcha, Anon Fuengkhajorn, Jukkrit Wungrath, and Pallop Siewchaisakul. 2025. "Dental Service Provision and Oral Health Conditions of Children Aged 0–12 Years, Northern Thailand: Transferring of Sub-District Health Promotion Hospitals Policy Era" Healthcare 13, no. 8: 874. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13080874

APA StyleSingweratham, N., Fuengkhajorn, A., Wungrath, J., & Siewchaisakul, P. (2025). Dental Service Provision and Oral Health Conditions of Children Aged 0–12 Years, Northern Thailand: Transferring of Sub-District Health Promotion Hospitals Policy Era. Healthcare, 13(8), 874. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13080874