Prospective Comparative Study of EMSella Therapy and Surgical Anterior Colporrhaphy for Urinary Incontinence: Outcomes and Efficacy

Abstract

1. Introduction

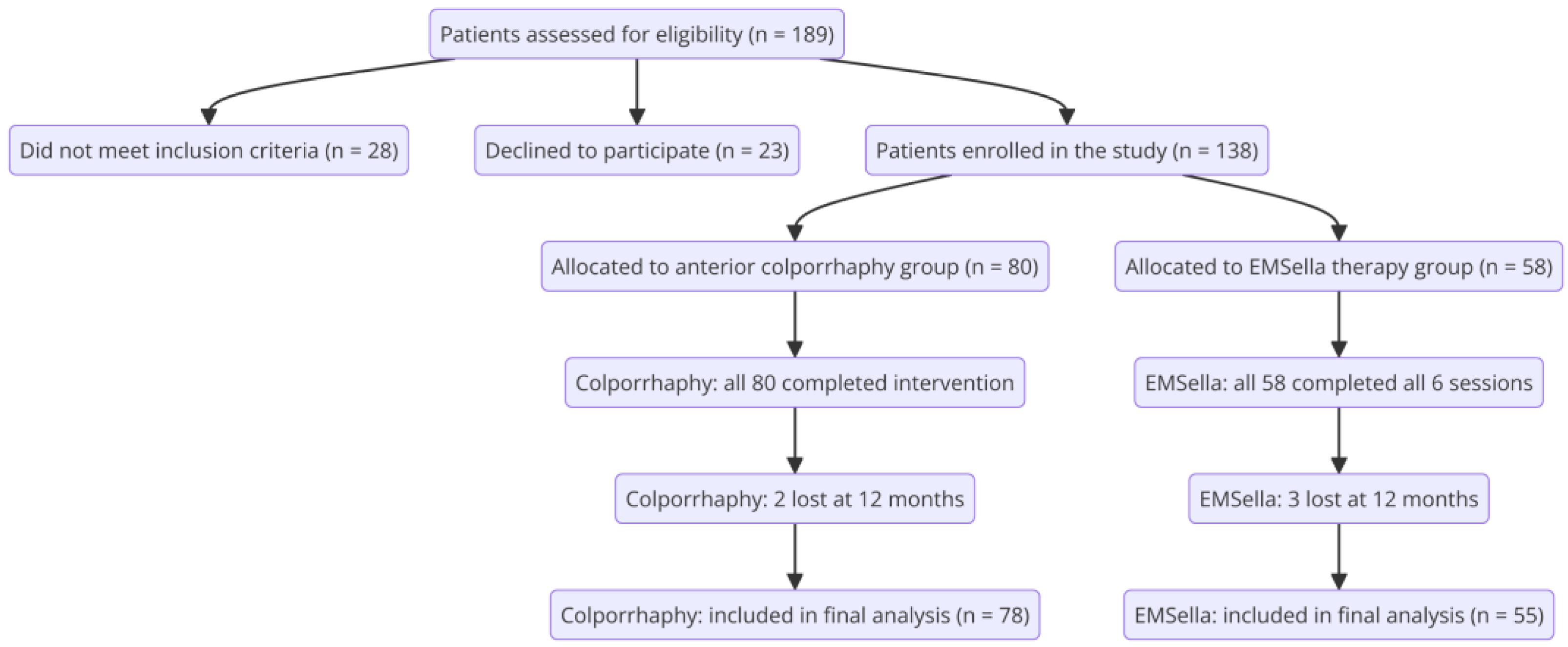

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patient Populations

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- Women aged 40–75 years diagnosed with symptomatic stage II cystocele, confirmed by POP-Q examination, and presenting with stress urinary incontinence (SUI), as determined by standardized urodynamic assessments, including uroflowmetry, cough stress test, and urethral pressure profilometry. Diagnosis of SUI was confirmed by the presence of involuntary urine leakage during increased intra-abdominal pressure in the absence of detrusor overactivity.

- Women in menopause.

- Hemodynamic stability and controlled comorbidities.

- Written informed consent for participation in the study and completion of post-intervention questionnaires.

- The ICIQ-UI score confirmed the presence of urinary incontinence symptoms.

- Availability for post-intervention follow-up at 6 months and 1 year.

- Absence of prior surgical interventions on the pelvic floor.

- Patients treated according to standardized protocols for EMSella or anterior colporrhaphy.

- Accurate completion of clinical and follow-up records.

- A maximum of two vaginal deliveries.

- Patients with documented active infections (e.g., urinary tract or vaginal infections).

- Recent use (within the past 6 months) of antibiotics, probiotics, or other therapies influencing the microbiota.

- Pregnancy or breastfeeding.

- Undergoing hormonal therapy.

- Untreated endocrine disorders.

- Patients with documented hormonal imbalances.

- Patients with confirmed diagnoses of neurological disorders.

- History of spinal cord injuries affecting urinary function.

- Urinary incontinence associated with diabetic neuropathy.

- Patients with a BMI > 30 (obesity).

- Women engaging in high-impact sports.

- Active smokers or those with a long-term history of smoking.

- Women undergoing pharmacological treatments associated with urinary incontinence (e.g., diuretics, sedatives).

- Individuals with genetic conditions affecting urinary control.

- Women with documented diagnoses of connective tissue disorders with a genetic basis.

- Patients with documented anxiety or depression disorders.

- Women reporting significant stress as a trigger for symptoms.

- Urinary incontinence associated with psychosomatic disorders.

- Patients with urge urinary incontinence (UUI), mixed urinary incontinence (MUI), neurogenic bladder, or severe pelvic floor dysfunction requiring immediate surgical intervention.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.4. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abu-Huwaij, R.; Al-Shalabi, R.; Alkhader, E.; Almasri, F.N. Urinary Incontinence and Quality of Life in Women of Central Jordan: A Cross-Sectional Study. Clin. Pract. 2024, 14, 1921–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zargham, M.; Alizadeh, F.; Moayednia, A.; Haghdani, S.; Nouri-Mahdavi, K. The role of pelvic organs prolapse in the etiology of urinary incontinence in women. Adv. Biomed. Res. 2013, 2, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chung, S.H.; Kim, W.B. Various Approaches and Treatments for Pelvic Organ Prolapse in Women. J. Menopausal Med. 2018, 24, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kwon, B.E.; Kim, G.Y.; Son, Y.J. Pathophysiology of stress urinary incontinence: A review of the literature. Int. Neurourol. J. 2020, 24, 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, P.D.; Amrute, K.V.; Badlani, G.H. Pelvic organ prolapse and stress urinary incontinence: Role of urethral support. Am. J. Obs. Gynecol. 2022, 226, e1–e175. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A.L.; Patel, D.V.; DeLancey, J.O. The impact of detrusor overactivity on quality of life in women with urinary incontinence. J. Urol. 2021, 206, 1116–1123. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Ren, L.; Liu, X.; Liu, J.; Ling, Q. Underactive Bladder and Detrusor Underactivity: New Advances and Prospectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 15517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tarcan, T.; Mangir, N. Evaluation and management of bladder outlet obstruction in women. Curr. Urol. Rep. 2022, 23, 45–56. [Google Scholar]

- Ghetti, C.; Gregory, W.T.; Clark, A.L. Anatomical and functional factors in female urinary incontinence: A comprehensive review. Obs. Gynecol. Surv. 2021, 76, 231–242. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, P.C.; Tsui, W.L.; Ding, D.C. Comparison of the surgical outcomes between paravaginal repair and anterior colporrhaphy: A retrospective case-control study. Tzu Chi Med. J. 2024, 36, 412–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Iyer, S.; Seitz, M.; Tran, A.; Reis, R.S.; Botros, C.; Lozo, S.; Botros, S.; Sand, P.; Tomezsko, J.; Wang, C.; et al. Anterior Colporrhaphy With and Without Dermal Allograft: A Randomized Control Trial With Long-Term Follow-Up. Female Pelvic Med. Reconstr. Surg. 2019, 25, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo, T.S.; Pue, L.B.; Tan, Y.L.; Wu, P.Y. Long-term outcomes of synthetic transobturator nonabsorbable anterior mesh versus anterior colporrhaphy in symptomatic, advanced pelvic organ prolapse surgery. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2014, 25, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukanović, D.; Kunič, T.; Batkoska, M.; Matjašič, M.; Barbič, M. Effectiveness of Magnetic Stimulation in the Treatment of Urinary Incontinence: A Systematic Review and Results of Our Study. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 5210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sammer, M.; Porcari, J.P.; Phillips, S.A.; Foster, C. Noninvasive High-Intensity Focused Electromagnetic Therapy in the Treatment of Female Urinary Incontinence: A Systematic Review. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2025, 44, 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Long, C.Y.; Lin, K.L.; Yeh, J.L.; Feng, C.W.; Loo, Z.X. Effect of High-Intensity Focused Electromagnetic Technology in the Treatment of Female Stress Urinary Incontinence. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Alinsod, R. Safety and Efficacy of a Non-Invasive High-Intensity Focused Electromagnetic Field (HIFEM) Device for Treatment of Urinary Incontinence and Enhancement of Quality of Life. Lasers Surg. Med. 2019, 51, 760–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silantyeva, E.; Zarkovic, D.; Astafeva, E.; Soldatskaia, R.; Orazov, M.; Belkovskaya, M.; Kurtser, M.; Academician of the Russian Academy of Sciences. A Comparative Study on the Effects of High-Intensity Focused Electromagnetic Technology and Electrostimulation for the Treatment of Pelvic Floor Muscles and Urinary Incontinence in Parous Women: Analysis of Posttreatment Data. Female Pelvic Med. Reconstr. Surg. 2021, 27, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shabataev, V.; Saadat, S.H.; Elterman, D.S. Management of erectile dysfunction and LUTS/incontinence: The two most common, long-term side effects of prostate cancer treatment. Can. J. Urol. 2020, 27 (Suppl. S1), 17–24. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Halpern-Elenskaia, K.; Umek, W.; Bodner-Adler, B.; Hanzal, E. Anterior colporrhaphy: A standard operation? Systematic review of the technical aspects of a common procedure in randomized controlled trials. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2018, 29, 781–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Elena, S.; Dragana, Z.; Ramina, S.; Evgeniia, A.; Orazov, M. Electromyographic Evaluation of the Pelvic Muscles Activity After High-Intensity Focused Electromagnetic Procedure and Electrical Stimulation in Women With Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. Sex. Med. 2020, 8, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Persu, C.; Chapple, C.R.; Cauni, V.; Gutue, S.; Geavlete, P. Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification System (POP-Q)—A new era in pelvic prolapse staging. J. Med. Life 2011, 4, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Spencer, J.; Hadden, K.; Brown, H.; Oliphant, S.S. Considering Low Health Literacy: How Do the Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory-Short Form 20 and Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire-Short Form 7 Measure Up? Female Pelvic Med. Reconstr. Surg. 2019, 25, 145–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Barber, M.D.; Walters, M.D.; Bump, R.C. Short forms of two condition-specific quality-of-life questionnaires for women with pelvic floor disorders (PFDI-20 and PFIQ-7). Am. J. Obs. Gynecol. 2005, 193, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garratt, A.M.; Helgeland, J.; Gulbrandsen, P. Five-point scales outperform 10-point scales in a randomized comparison of item scaling for the Patient Experiences Questionnaire. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011, 64, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripperda, C.M.; Kowalski, J.T.; Balgobin, S.; Wai, C.Y. Long-term follow-up of native tissue anterior vaginal wall repair. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2020, 31, 2061–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svabik, K.; Martan, A.; Masata, J.; Hubka, P.; Haakova, L. Anterior Colporrhaphy and Paravaginal Repair for Anterior Vaginal Wall Prolapse: A Review. Medicina 2024, 60, 1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutman, R.E.; Maher, C. Vaginal and laparoscopic surgery for pelvic organ prolapse. Clin. Obs. Gynecol. 2022, 65, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, T.S.; Pue, L.B.; Hung, T.H.; Wu, P.Y.; Tan, Y.L. Long-term outcome of native tissue reconstructive vaginal surgery for advanced pelvic organ prolapse at 86 months: Hysterectomy versus hysteropexy. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2015, 41, 1099–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fehring, V.; Weber-Amann, J.; Flisser, A.J. Ten-year follow-up of native tissue prolapse repair: Success rates and patient satisfaction. Life 2024, 14, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Your Pelvic Floor. Anterior Vaginal Repair—Success Rates. International Urogynecological Association (IUGA), 2023. Available online: https://www.yourpelvicfloor.org/conditions/anterior-vaginal-repair (accessed on 11 December 2024).

- Melbourne Bladder Clinic. Cystocele Repair—Long-Term Outcomes. Bladder Clinic Australia, 2023. Available online: https://bladderclinic.com.au/procedures/female-pelvic-medicine/cystocele-repair (accessed on 13 December 2024).

- Taylor, C.; Berkowitz, C.; Shull, B. Long-term outcomes of anterior colporrhaphy with pubovaginal sling reinforcement for high-grade cystocele. J. Pelvic Med. Surg. 2021, 27, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zyczynski, H.M.; Carey, M.P.; Smith, A.R.; Gauld, J.M.; Robinson, D.; Sikirica, V.; Reisenauer, C.; Slack, M. Prosima Study Investigators. One-year clinical outcomes after prolapse surgery with nonanchored mesh and vaginal support device. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 203, 587.e1–587.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vergeldt, T.F.; Weemhoff, M.; IntHout, J.; Kluivers, K.B. Risk factors for pelvic organ prolapse and its recurrence: A systematic review. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2015, 26, 1559–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diez-Itza, I.; Aizpitarte, I.; Becerro, A.; Arrue, M.; Murgiondo, A.; Sarasqueta, C. Recurrence risk is associated with preoperatively advanced prolapse stage and levator ani muscle defects. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2017, 28, 931–937. [Google Scholar]

- Lallemant, M.; Clermont-Hama, Y.; Giraudet, G.; Rubod, C.; Delplanque, S.; Kerbage, Y.; Cosson, M. Long-Term Outcomes after Pelvic Organ Prolapse Repair in Young Women. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nüssler, E.; Granåsen, G.; Bixo, M.; Löfgren, M. Long-term outcome after routine surgery for pelvic organ prolapse-A national register-based cohort study. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2022, 33, 1863–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pfirrmann, D.; Gesslein, M.; Schile, S.; Sigl, P.; Kiechle, M.; Reisenauer, C. Noninvasive high-intensity focused electromagnetic therapy in the treatment of urinary incontinence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2023, 42, 275–285. [Google Scholar]

- Radzimińska, A.; Strączyńska, A.; Weber-Rajek, M.; Styczyńska, H.; Strojek, K.; Piekorz, Z. The impact of pelvic floor muscle training on the quality of life of women with urinary incontinence: A systematic literature review. Clin. Interv. Aging 2018, 13, 957–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davila, G.W. Nonsurgical outpatient therapies for the management of female stress urinary incontinence: Long-term effectiveness and durability. Adv. Urol. 2011, 2011, 176498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Barber, M.D.; Brubaker, L.; Burgio, K.L.; Richter, H.E.; Nygaard, I.; Weidner, A.C.; Menefee, S.A.; Lukacz, E.S.; Norton, P.; Schaffer, J.; et al. Comparison of 2 transvaginal surgical approaches and perioperative behavioral therapy for apical vaginal prolapse: The OPTIMAL randomized trial. JAMA 2014, 311, 1023–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, S.; Elsayed, M.; Tharwat, M.; Awad, S.; Abdelwahab, M.; El-Hefnawy, A.S. Evaluation of possible side effects in the treatment of urinary incontinence with magnetic stimulation: A prospective, uncontrolled clinical trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wihersaari, O.; Mentula, M.; Kuismanen, K.; Rahkola-Soisalo, P.; Härkki, P. Sexual activity and dyspareunia after pelvic organ prolapse surgery: A 5-year follow-up study. Eur. Urol. Open Sci. 2022, 44, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, H.; Akınsal, E.C.; Sönmez, G.; Baydilli, N.; Demirci, D. Is the High-Intensity Focused Electromagnetic Energy an Effective Treatment for Urinary Incontinence in Women? Ther. Clin. Risk. Manag. 2024, 20, 811–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Characteristics | EMSella Therapy (n = 55) | Anterior Colporrhaphy (n = 78) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (years) | 49.5 ± 6.9 | 51.2 ± 7.0 | 0.167 |

| Body mass index (BMI) | 25.1 ± 3.8 | 24.4 ± 4.0 | 0.312 |

| PFDI-20 score (pre-treatment) | 79.2 ± 13.1 | 80.5 ± 12.9 | 0.570 |

| Chronic constipation (%) | 12 (21.81%) | 16 (20.51%) | 0.761 |

| Severity of incontinence (ICIQ-UI, mean score) | 13.4 ± 3.3 | 13.7 ± 3.4 | 0.612 |

| Symptom duration (years) | 3.8 ± 1.9 | 4.0 ± 2.0 | 0.563 |

| Objective Parameter | EMSella Therapy (n = 55) | Anterior Colporrhaphy (n = 78) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Prolapse Reduction (POP-Q) | |||

| Post-treatment improvement | To stage 1 or better: 35 (63.63%) | To stage 0: 69 (88.46%) | <0.001 * |

| No improvement | 20 (36.36%) | 9 (11.53%) | <0.001 * |

| 2. Bladder Function (Urodynamic Tests) | |||

| Post-treatment normalization | 55% (30/55) | 56 (71.78%) | 0.044 * |

| Residual dysfunction post-treatment | 45% (25/55) | 22 (28.20%) | 0.041 * |

| 3. Prolapse Recurrence | |||

| Recurrence at 6 months | 10 (18.18%) | 7 (8.97%) | 0.094 |

| Recurrence at 1 year | 17 (30.90%) | 11 (14.10) | 0.032 * |

| Parameter | MSella Therapy (n = 55) | Anterior Colporrhaphy (n = 78) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prolapse Reduction (POP-Q Staging) | |||

| Post-treatment stage 0 (no prolapse) | 18 (32.72%) | 66 (84.61%) | <0.001 * |

| Post-treatment stage 1 | 24 (43.63%) | 10 (12.82%) | 0.002 * |

| No improvement (stage ≥ 2) | 13 (23.63%) | 2 (2.56%) | <0.001 * |

| Urodynamic Test Results | |||

| Maximum urethral closure pressure (cmH2O) | 38.5 ± 7.2 | 42.8 ± 6.5 | 0.021 * |

| Post-void residual volume (mL) | 62.4 ± 14.3 | 8.1 ± 11.8 | 0.017 * |

| Bladder compliance (mL/cmH2O) | 2.7 ± 5.1 | 7.3 ± 4.8 | 0.039 * |

| Detrusor overactivity (%) | 16 (29.09%) | 12 (15.38%) | 0.044 * |

| Urinary incontinence severity | |||

| Q-UI Score (pre-treatment) | 13.4 ± 3.3 | 13.7 ± 3.4 | 0.612 |

| ICIQ-UI Score (post-treatment) | 8.2 ± 2.5 | 5.1 ± 2.1 | <0.001 * |

| Normalized Bladder Function (%) | 30 (54.54%) | 56 (71.79%) | 0.044 * |

| Subjective Parameter | EMSella Therapy (n = 55) | Anterior Colporrhaphy (n = 78) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Quality of Life (QoL) | |||

| Baseline PFDI-20 score | 79.2 ± 13.1 | 80.5 ± 12.9 | 0.570 |

| Post-treatment PFDI-20 score | 50.7 ± 10.5 | 40.4 ± 11.2 | <0.001 * |

| Change in PFDI-20 score (absolute) | 28.5 ± 10.2 | 40.1 ± 12.5 | <0.001 * |

| Baseline PFIQ-7 score | 75.8 ± 14.3 | 77.2 ± 13.7 | 0.569 |

| Post-treatment PFIQ-7 score | 52.1 ± 11.0 | 41.3 ± 10.7 | <0.001 * |

| Change in PFIQ-7 score (absolute) | 23.7 ± 9.8 | 35.9 ± 11.5 | <0.001 * |

| 2. Patient Satisfaction | |||

| Overall satisfaction (Likert scale 1–5) | 4.1 ± 0.7 | 4.5 ± 0.5 | 0.002 * |

| Patients “very satisfied” (score 4–5) | 45 (81.81%) | 71 (91.02%) | 0.091 |

| Preference for the same treatment (%) | 41 (74.54%) | 69 (88.46%) | 0.043 * |

| Complication/Adverse Effect | EMSella Therapy (n = 55) | Anterior Colporrhaphy (n = 78) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Overall rate of adverse effects (%) | 8 (14.54%) | 27 (34.61%) | 0.011 ** |

| 2. Specific Complications | |||

| Temporary irritation (%) * | 5 (9.09%) | 4 (5.12%) | 0.341 |

| Infections (e.g., UTI, vaginal) (%) | 2 (3.63%) | 11 (14.10%) | 0.025 ** |

| Dyspareunia (%) | 0 (0%) | 11 (14.10%) | <0.001 ** |

| Parameter | EMSella Therapy (n = 55) | Anterior Colporrhaphy (n = 78) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Time to Resume Daily Activities | |||

| <1 week (%) | 50 (90.90%) | 9 (11.53%) | <0.001 |

| 1–2 weeks (%) | 5 (9.09%) | 18 (23.09%) | <0.001 |

| >2 weeks (%) | 0 (0%) | 51 (65.38%) | <0.001 |

| Mean recovery time (days) | 2.3 ± 1.1 | 18.7 ± 6.5 | <0.001 |

| 2. Impact on Social and Professional Life | |||

| Temporary disruption of social activities (%) | 8 (14.54%) | 30 (38.46%) | 0.002 |

| Temporary inability to work (%) | 4 (7.27%) | 63 (80.76%) | <0.001 |

| Patient-reported comfort (Likert scale 1–5) | 4.6 ± 0.4 | 3.8 ± 0.7 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sacarin, G.; Abu-Awwad, A.; Razvan, N.; Craina, M.; Prodan, M.; Timircan, M.-O.; Betea, R.; Dinu, A.; Abu-Awwad, S.-A. Prospective Comparative Study of EMSella Therapy and Surgical Anterior Colporrhaphy for Urinary Incontinence: Outcomes and Efficacy. Healthcare 2025, 13, 864. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13080864

Sacarin G, Abu-Awwad A, Razvan N, Craina M, Prodan M, Timircan M-O, Betea R, Dinu A, Abu-Awwad S-A. Prospective Comparative Study of EMSella Therapy and Surgical Anterior Colporrhaphy for Urinary Incontinence: Outcomes and Efficacy. Healthcare. 2025; 13(8):864. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13080864

Chicago/Turabian StyleSacarin, Geanina, Ahmed Abu-Awwad, Nitu Razvan, Marius Craina, Mihaela Prodan, Madalina-Otilia Timircan, Razvan Betea, Anca Dinu, and Simona-Alina Abu-Awwad. 2025. "Prospective Comparative Study of EMSella Therapy and Surgical Anterior Colporrhaphy for Urinary Incontinence: Outcomes and Efficacy" Healthcare 13, no. 8: 864. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13080864

APA StyleSacarin, G., Abu-Awwad, A., Razvan, N., Craina, M., Prodan, M., Timircan, M.-O., Betea, R., Dinu, A., & Abu-Awwad, S.-A. (2025). Prospective Comparative Study of EMSella Therapy and Surgical Anterior Colporrhaphy for Urinary Incontinence: Outcomes and Efficacy. Healthcare, 13(8), 864. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13080864