Determinants of Patients’ Perception of Primary Healthcare Quality: Empirical Analysis in the Brazilian Health System

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Datasets

2.3. Variables

- Individual characteristics: sex (binary: male, female), age (continuous: years), skin color/ethnicity (categorical: black, brown, indigenous, white, and yellow), educational attainment (continuous: years of education), occupational status (binary: unemployed and employed), health status (binary: regular or less and good or very good), diagnosis of multimorbidity (binary: no and yes), health issue severity (binary: no and yes), health insurance ownership (binary: no and yes);

- Household characteristics: household residents (discrete: individuals living in the household), household income per capita in adult equivalents (continuous: dollars in 2022 purchase power parity, PPP), area of residence (binary: rural, and urban);

- Health service characteristics: type of healthcare facility (binary: public, and private), source of healthcare financing (categorical: health insurance, out of pocket, and SUS), healthcare effectiveness (proportion of healthcare visits required to solve health issues during the last two weeks);

- Policy-level characteristics: adherence to the PMAQ-AB (binary: low and high adherence to the payment for performance program);

- Control variables: state (categorical: 26 states and the federal capital), year of the survey.

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Limitations and Contributions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Marginal Predictions—PHC Quality | 1998 | 2003 | 2008 | 2013 | 2019 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex—Female | Margin | 0.978 | 0.978 | 0.973 | 0.985 | 0.964 |

| SE | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.002 | |

| Sex—Male | Margin | 0.981 | 0.981 | 0.973 | 0.988 | 0.978 |

| SE | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 | |

| Pairwise comparison | Contrast | −0.003 | −0.003 | 0.000 | −0.003 | −0.014 * |

| SE | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.003 | |

| Good health status | Margin | 0.984 | 0.985 | 0.982 | 0.994 | 0.985 |

| SE | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | |

| Less than good health status | Margin | 0.974 | 0.972 | 0.962 | 0.960 | 0.920 |

| SE | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.004 | 0.005 | |

| Pairwise comparison | Contrast | 0.108 * | 0.012 * | 0.020 * | 0.035 * | 0.065 * |

| SE | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.004 | 0.005 | |

| Multimorbidity diagnosis—Yes | Margin | 0.976 | 0.975 | 0.965 | 0.990 | 0.977 |

| SE | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.002 | |

| Multimorbidity diagnosis—No | Margin | 0.982 | 0.981 | 0.977 | 0.976 | 0.949 |

| SE | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.004 | |

| Pairwise comparison | Contrast | −0.006 ‡ | −0.006 ‡ | −0.012 * | 0.015 * | 0.028 * |

| SE | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.004 | |

| Health issue severity—High | Margin | 0.966 | 0.990 | 0.992 | 0.998 | 0.990 |

| SE | 0.015 | 0.006 | 0.005 | 0.002 | 0.005 | |

| Health issue severity—Low | Margin | 0.979 | 0.978 | 0.972 | 0.986 | 0.972 |

| SE | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.002 | |

| Pairwise comparison | Contrast | −0.013 | 0.012 | 0.021 * | 0.012 * | 0.018 ‡ |

| SE | 0.015 | 0.006 | 0.005 | 0.002 | 0.006 | |

| Rural area | Margin | 0.981 | 0.986 | 0.979 | 0.986 | 0.968 |

| SE | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.332 | 0.004 | |

| Urban area | Margin | 0.979 | 0.978 | 0.972 | 0.986 | 0.969 |

| SE | 0.002 | 0.106 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.002 | |

| Pairwise comparison | Contrast | 0.002 | 0.008 ‡ | 0.007 § | 0.000 | −0.001 |

| SE | 0.004 | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.004 | |

References

- Bitton, A.; Ratcliffe, H.L.; Veillard, J.H.; Kress, D.H.; Barkley, S.; Kimball, M.; Secci, F.; Wong, E.; Basu, L.; Taylor, C.; et al. Primary health care as a foundation for strengthening health systems in low- and middle-income countries. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2017, 32, 566–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendes, E.V. Health care networks. Cienc. Saude Coletiva 2010, 15, 2297–2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos, R.T.O.; Ferrer, A.L.; Gama, C.A.P.; Campos, G.W.S.; Trapé, T.L.; Dantas, D.V. Assessment of quality of access in primary care in a large Brazilian city in the perspective of users. Saude Debate 2014, 38, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aday, L.A.; Andersen, R. A framework for the study of access to medical care. Health Serv. Res. 1974, 9, 208–220. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1071804/ (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- Fournier, J.; Heale, R.; Rietze, L. I can’t wait: Advanced access decreases wait times in primary healthcare. Healthc. Q. 2012, 15, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paula, C.C.; Silva, C.B.; Tassinari, T.T.; Padoin, S.M.M. Factors that affect first contact access in the primary health care: Integrative review. Rev. Pesq. Cuid. Fund. Online 2016, 8, 4056–4078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Britnell, M. Search of the Perfect Health System; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2015; 247p. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, G.; Sarti, F.M.; Ferreira, F.F.; Diaz, M.D.M.; Campino, A.C.C. Analysis of the evolution and determinants of income-related inequalities in the Brazilian health system, 1998–2008. Rev. Panam. De Salud Pública 2013, 33, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil. Política Nacional de Atenção Básica; Ministério da Saúde: Brasília, Brazil, 2012; Available online: http://189.28.128.100/dab/docs/publicacoes/geral/pnab.pdf (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Brasil. Portaria n°. 2.436, de 22 de Setembro de 2017; Ministério da Saúde: Brasília, Brazil, 2017. Available online: http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/gm/2017/prt2436_22_09_2017.html (accessed on 5 February 2020).

- Brasil. Saúde Mais Perto de Você—Acesso e Qualidade: Programa Nacional de Melhoria do Acesso e da Qualidade da Atenção Básica (PMAQ); Ministério da Saúde: Brasília, Brazil, 2014; 62p. Available online: https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/acesso_qualidade_programa_melhoria_pmaq.pdf (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Santos, A.F.; Sobrinho, D.F.; Araujo, L.L.; Procópio, C.S.D.; Lopes, E.A.S.; Lima, A.M.L.D.; Reis, C.M.R.; Abreu, D.M.X.; Jorge, A.O.; Matta-Machado, A.T. Incorporation of Information and Communication Technologies and quality of primary healthcare in Brazil. Cad. Saude Publica 2017, 33, e00172815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doubova, S.V.; Guanais, F.C.; Pérez-Cuevas, R.; Canning, D.; Macinko, J.; Reich, M.R. Attributes of patient-centered primary care associated with the public perception of good healthcare quality in Brazil, Colombia, Mexico and El Salvador. Health Policy Plan. 2016, 31, 834–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protasio, A.P.L.; Gomes, L.B.; Machado, L.S.; Valença, A.M.G. User satisfaction with primary health care by region in Brazil: 1st. cycle of external evaluation from PMAQ-AB. Cienc. Saude Coletiva 2017, 22, 1829–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurgel, G.D., Jr.; Kristensen, S.R.; Silva, E.N.; Gomes, L.B.; Barreto, J.O.M.; Kovacs, R.J.; Sampaio, J.; Bezerra, A.F.B.; Brito e Silva, K.S.; Shimizu, H.E.; et al. Pay-for-performance for primary health care in Brazil: A comparison with England’s Quality Outcomes Framework and lessons for the future. Health Policy 2023, 128, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, N.R.; Silva, P.R.F.; Jatobá, A. Performance assessment of primary health care: Balance and perspective for the ‘Previne Brasil’ program. Saude Debate 2022, 46, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assis, M.M.A.; Jesus, W.L.A. Access to health services: Approaches, concepts, policies and analysis model. Cienc. Saude Coletiva 2012, 17, 2865–2875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trad, L.A.B.; Bastos, A.C.S.; Santana, E.M.; Nunes, M.O. Ethnography study about user satisfaction of Family Health Program in Bahia. Cienc. Saude Coletiva 2002, 7, 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harzheim, E.; Duncan, B.B.; Stein, A.T.; Cunha, C.R.H.; Gonçalves, M.R.; Trindade, T.G.; Oliveira, M.M.C.; Pinto, M.E.B. Quality and effectiveness of different approaches to primary care delivery in Brazil. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2006, 6, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macinko, J.; Almeida, C.; Sá, P.K. A rapid assessment methodology for the evaluation of primary care organization and performance in Brazil. Health Policy Plan 2007, 22, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago, R.F.; Mendes, A.C.G.; Miranda, G.M.D.; Duarte, P.O.; Furtado, B.M.A.S.M.; Souza, W.V. Quality of care in the family healthcare units in the city of Recife: User perception. Cienc. Saude Coletiva 2013, 18, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paula, W.K.A.S.; Samico, I.C.; Caminha, M.F.C.; Batista Filho, M.; Silva, S.L. Primary health care assessment from the users’ perspectives: A systematic review. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2016, 50, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facchini, L.A.; Tomasi, E.; Dilélio, A.S. Quality of primary health care in Brazil: Advances, challenges and perspectives. Saude Debate 2018, 42, 208–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, L.A.; Scatena, J.H. The evaluation of primary health care in Brazil: An analysis of the scientific production between 2007 and 2017. Saude Soc. 2019, 28, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekhon, M.; Cartwright, M.; Francis, J.J. Acceptability of healthcare interventions: An overview of reviews and development of a theoretical framework. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houghton, N.; Bascolo, E.; del Riego, A. Monitoring access barriers to health services in the Americas: A mapping of household surveys. Pan Am. J. Public Health 2020, 44, e96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilger, J.; Pletscher, M.; Müller, T. Separating the wheat from the chaff: How to measure hospital quality in routine data? Health Serv. Res. 2024, 59, e14282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, M.-J.; Ahmed, S.; Lorenzetti, D.; Jolley, R.J.; Manalili, K.; Zelinsky, S.; Quan, H.; Lu, M. Measuring patient-centred system performance: A scoping review of patient-centred care quality indicators. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e023596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munar, W.; Snilstveit, B.; Aranda, L.E.; Biswas, N.; Baffour, T.; Stevenson, J. Evidence gap map of performance measurement and management in primary healthcare systems in low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Glob. Health 2019, 4 (Suppl. S8), e001451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyai, R.; Upadhyai, N.; Jain, A.K.; Roy, H.; Pant, V. Health care service quality: A journey so far. Benchmarking 2020, 27, 1893–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, D.C.; Vieira, I.; Pedro, M.I.; Caldas, P.; Varela, M. Patient satisfaction with healthcare services and the techniques used for its assessment: A systematic literature review and a bibliometric analysis. Healthcare 2023, 11, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dover, D.C.; Belon, A.P. The health equity measurement framework: A comprehensive model to measure social inequities in health. Int. J. Equity Health 2019, 18, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cookson, R.; Doran, T.; Asaria, M.; Gupta, I.; Mujica, F.P. The inverse care law re-examined: A global perspective. Lancet 2021, 397, 828–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawshaw, P.; Gray, J.; Haighton, C.; Lloyd, S. Health inequalities and health-related economic inactivity: Why good work needs good health. Public Health Pract. 2024, 8, 100555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donabedian, A. Quality assessment and monitoring. Eval. Health Prof. 1983, 6, 363–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donabedian, A. Evaluating the quality of medical care. Milbank Q. 2005, 83, 691–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endeshaw, B. Healthcare service quality measurement models: A review. J. Health Res. 2021, 35, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization/Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development/World Bank. Delivering Quality Health Services: A Global Imperative for Universal Health Coverage; World Health Organization, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, and World Bank: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241513906 (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Gulliford, M. Access to healthcare. In Healthcare Public Health: Improving Health Services Through Population Science; Gulliford, M., Jessop, E., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020; pp. 69–81. [Google Scholar]

- Santana, I.R.; Mason, A.; Gutacker, N.; Kasteridis, P.; Santos, R.; Rice, N. Need, demand, supply in health care: Working definitions, and their implications for defining access. Health Econ. Policy Law 2023, 18, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhal, A.; Sharma, A. Exploring patient’s experiential values and its impact on service quality assessment by Indian consumers in public health institution: A qualitative study. J. Public Aff. 2022, 22 (Suppl. S1), e2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooney, G.H. Equity in healthcare: Confronting the confusion. Eff. Health Care 1983, 1, 179–185. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10310519/ (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- Penchansky, R.; Thomas, J.W. The concept of access: Definition and relationship to consumer satisfaction. Med. Care 1981, 19, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). The World Health Report 2000. Health Systems: Improving Performance; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/924156198X (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Gulliford, M.; Figueroa-Munoz, J.; Morgan, M.; Gibson, D.H.B.; Beech, R.; Hudson, M. What does ‘access to health care’ mean? J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2002, 7, 186–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, A.; Mossialos, E. Equity of access to health care: Outlining the foundations for action. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2004, 58, 655–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, O. Access to healthcare in developing countries: Breaking down demand side barriers. Cad. Saude Publica 2007, 23, 2820–2834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savedoff, W.D. A Moving Target: Universal Access to Healthcare Services in Latin America and the Caribbean; Working Paper #667; Inter-American Development Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levesque, J.-F.; Harris, M.F.; Russell, G. Patient-centred access to health care: Conceptualising access at the interface of health systems and populations. Int. J. Equity Health 2013, 12, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brizan, S.; Martin, R.; Martin, C.; La Foucade, A.; Sarti, F.M.; McLean, R. An empirically validated framework for measuring patient’s acceptability of health care in Multi-Island Micro States. Health Policy Plan. 2023, 38, 464–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siméant, S. Problem-solving capacity for meeting health care demands at the primary level in Chile, 1981. Bol. Oficina Sanit Panam. 1984, 97, 125–141. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6238603/ (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- Turrini, R.N.T.; Lebrão, M.L.; Cesar, C.L.G. Case-resolving capacity of health care services according to a household survey: Users’ perceptions. Cad. Saude Publica 2008, 24, 663–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jindal, M.; Chaiyachati, K.H.; Fung, V.; Manson, S.M.; Mortensen, K. Eliminating health care inequities through strengthening access to care. Health Serv. Res. 2023, 58 (Suppl. S3), 300–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, D.; Rouleau, K.; Winkelmann, J.; Kringos, D.; Jakab, M.; Khalid, F. (Eds.) Implementing the Primary Health Care Approach: A Primer; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240090583 (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Solar, O.; Irwin, A. A Conceptual Framework for Action on the Social Determinants of Health; Social Determinants of Health Discussion Paper 2 (Policy and Practice); WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241500852 (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Arghittu, A.; Castiglia, P.; Dettori, M. Family medicine and primary healthcare: The past, present and future. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deaton, A. The Analysis of Household Surveys; John Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. World Development Indicators—PPP Conversion Factor; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; Available online: https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators# (accessed on 14 October 2024).

- Lima, J.G.; Giovanella, L.; Fausto, M.C.R.; Bousquat, A.; Silva, E.V. Essential attributes of primary health care: National results of PMAQ-AB. Saude Debate 2018, 42, 52–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, L.B.; Mota, M.V.; Porto, M.M.A.; Fernandes, C.S.G.V.; Santos, E.T.; Oliveira, J.P.M.; Mota, T.C.; Porto, A.L.S.; Alencar, M.N.A. Assessment of the quality of primary health care in Fortaleza, Brazil, from the perspective of adult service users in 2019. Cienc Saude Coletiva 2021, 26, 2083–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maun, A.; Wessman, C.; Sundvall, P.D.; Thorn, J.; Björkelund, C. Is the quality of primary healthcare services influenced by the healthcare centre’s type of ownership? An observational study of patient perceived quality, prescription rates and follow-up routines in privately and publicly owned primary care centres. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2015, 15, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shayo, E.H.; Senkoro, K.P.; Momburi, R.; Olsen, Ø.E.; Byskov, J.; Makundi, E.A.; Kamuzora, P.; Mboera, L.E.G. Access and utilisation of healthcare services in rural Tanzania: A comparison of public and non-public facilities using quality, equity, and trust dimensions. Glob. Public Health 2016, 11, 407–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, T.; Eriksson, N.; Müllern, T. Patients’ perceptions of quality in Swedish primary care—a study of differences between private and public ownership. J. Health Organ. Manag. 2021, 35, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, S.Y.S.; Kung, K.; Griffiths, S.M.; Carthy, T.; Wong, M.C.S.; Lo, S.V.; Chung, V.C.H.; Goggins, W.B.; Starfield, B. Comparison of primary care experiences among adults in general outpatient clinics and private general practice clinics in Hong Kong. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pullicino, G.; Sciortino, P.; Calleja, N.; Schäfer, W.; Boerma, W.; Groenewegen, P. Comparison of patients’ experiences in public and private primary care clinics in Malta. Eur. J. Public Health 2015, 25, 399–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, K.O.C.S.; Ribeiro, C.J.N.; Santos, J.Y.S.; Araújo, D.C.; Peixoto, M.V.S.; Fracolli, L.A.; Santos, A.D. Access, scope and resoluteness of primary health care in northeastern Brazil. Acta Paul. Enferm. 2022, 35, eAPE01076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A.W.D.; Mello, E.C.A.; Candeia, R.M.S.; Silva, G.; Gomes, L.B.; Sampaio, J. Performance payment to the Primary Care Teams: Analysis from the PMAQ-AB cycles. Saude Debate 2021, 45, 1060–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, R.; Barreto, J.O.M.; Silva, E.N.; Borghi, J.; Kristensen, S.R.; Costa, D.R.T.; Gomes, L.B.; Gurgel, G.D., Jr.; Sampaio, J.; Powell-Jackson, T. Socioeconomic inequalities in the quality of primary care under Brazil’s national pay-for-performance programme: A longitudinal study of family health teams. Lancet Glob. Health 2021, 9, e331–e339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodrich, G.W.; Lazenby, J.M. Elements of patient satisfaction: An integrative review. Nurs. Open 2023, 10, 1258–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellón, J.Á.; Lardelli, P.; Luna, J.D.D.; Delgado, A. Validity of self reported utilisation of primary health care services in an urban population in Spain. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2000, 54, 544–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jatrana, S.; Crampton, P. Do financial barriers to access to primary health care increase the risk of poor health? Longitudinal evidence from New Zealand. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 288, 113255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | N | Frequency | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | ||||

| Sex | 136,441 | 90,893 | 66.62 | 0 | 1 |

| Age ‡ | 136,429 | 45.67 | 17.41 | 18 | 108 |

| Skin color/ethnicity | |||||

| Black | 136,431 | 11,235 | 8.23 | 0 | 1 |

| Brown | 136,431 | 56,065 | 41.09 | 0 | 1 |

| Indigenous | 136,431 | 624 | 0.46 | 0 | 1 |

| White | 136,431 | 67,710 | 49.63 | 0 | 1 |

| Yellow | 136,431 | 797 | 0.58 | 0 | 1 |

| Educational attainment ‡ | 129,609 | 8.69 | 5.14 | 0 | 18 |

| Occupational status | 134,189 | 71,578 | 53.34 | 0 | 1 |

| Household residents ‡ | 167,624 | 3.12 | 1.92 | 1 | 25 |

| Household income per capita in PPP ‡ | 164,935 | 805.03 | 1573.73 | 0.00 | 129,358.70 |

| Health insurance ownership | 136,402 | 50,557 | 37.06 | 0 | 1 |

| Good health status | 167,624 | 113,939 | 67.97 | 0 | 1 |

| Multimorbidity | 167,624 | 96,668 | 57.67 | 0 | 1 |

| Type of healthcare facility | |||||

| Public | 127,536 | 66,731 | 52.32 | 0 | 1 |

| Private | 127,536 | 60,522 | 47.45 | 0 | 1 |

| Healthcare financing | |||||

| Health insurance | 127,536 | 38,517 | 30.20 | 0 | 1 |

| Out of pocket | 127,536 | 26,315 | 20.63 | 0 | 1 |

| SUS | 127,536 | 62,704 | 49.52 | 0 | 1 |

| Perception of good healthcare quality | 167,624 | 164,193 | 97.95 | 0 | 1 |

| Healthcare effectiveness ‡ | 131,372 | 96.93 | 7.74 | 7.14 | 100.00 |

| Health issue severity | 128,212 | 1199 | 0.94 | 0 | 1 |

| Adherence to PMAQ-AB | 167,624 | 66,381 | 39.60 | 0 | 1 |

| Area | 167,624 | 23,699 | 14.14 | 0 | 1 |

| Characteristics | 1998 | 2003 | 2008 | 2013 | 2019 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||||

| Male * | 32.41 | 32.44 | 35.34 | 33.23 | 34.61 | 33.82 |

| Female * | 67.59 | 67.56 | 64.66 | 66.77 | 65.39 | 66.18 |

| Age ‡ | 43.63 | 44.65 | 45.70 | 47.98 | 49.55 | 46.90 |

| 0.34 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.24 | 0.19 | 0.10 | |

| Skin color/ethnicity | ||||||

| Black * | 5.81 | 6.26 | 7.46 | 8.57 | 10.94 | 8.32 |

| Brown * | 31.33 | 34.14 | 38.02 | 37.47 | 39.41 | 36.84 |

| Indigenous * | 0.27 | 0.20 | 0.36 | 0.49 | 0.48 | 0.39 |

| White * | 61.97 | 58.98 | 53.53 | 52.47 | 48.21 | 53.68 |

| Yellow * | 0.62 | 0.42 | 0.64 | 1.00 | 0.95 | 0.77 |

| Educational attainment ‡ | 7.42 | 7.85 | 8.54 | 9.26 | 10.06 | 8.89 |

| 0.24 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.03 | |

| Occupational status | ||||||

| Employed * | 53.13 | 52.72 | 56.79 | 51.67 | 50.79 | 52.81 |

| Unemployed * | 46.87 | 47.28 | 43.21 | 48.33 | 49.21 | 47.19 |

| Household residents ‡ | 3.99 | 3.75 | 3.55 | 3.29 | 3.06 | 3.44 |

| 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | |

| Household income per capita ‡ | 933.89 | 795.36 | 925.92 | 1174.43 | 1277.08 | 1065.46 |

| 84.14 | 13.44 | 13.61 | 41.98 | 26.53 | 15.32 | |

| Area | ||||||

| Urban * | 86.66 | 88.73 | 88.26 | 88.76 | 88.84 | 88.42 |

| Rural * | 13.34 | 11.27 | 11.74 | 11.24 | 11.16 | 11.58 |

| Region | ||||||

| North * | 4.00 | 4.30 | 5.24 | 5.00 | 5.84 | 5.05 |

| Northeast * | 21.13 | 22.45 | 22.48 | 21.72 | 23.20 | 22.35 |

| Southeast * | 49.58 | 48.26 | 47.98 | 48.17 | 47.84 | 48.23 |

| South * | 18.81 | 18.52 | 17.61 | 18.61 | 16.37 | 17.77 |

| Middle West * | 6.48 | 6.47 | 6.69 | 6.52 | 6.75 | 6.61 |

| Characteristics | 1998 | 2003 | 2008 | 2013 | 2019 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good health status * | 52.18 | 53.43 | 52.37 | 75.95 | 75.22 | 64.40 |

| Multimorbidity * | 38.77 | 36.36 | 36.49 | 70.32 | 70.04 | 54.02 |

| Health insurance ownership * | 41.25 | 38.67 | 37.42 | 37.35 | 38.65 | 38.44 |

| Type of healthcare facility | ||||||

| Public * | 46.47 | 52.01 | 51.70 | 56.52 | 49.84 | 51.70 |

| Private * | 53.19 | 47.80 | 48.15 | 43.28 | 49.98 | 48.10 |

| Unknown * | 0.34 | 0.19 | 0.15 | 0.20 | 0.18 | 0.20 |

| Healthcare funding | ||||||

| Health insurance * | 32.04 | 30.75 | 28.98 | 31.05 | 33.48 | 31.33 |

| Out of pocket * | 20.39 | 18.89 | 22.98 | 17.70 | 22.47 | 20.60 |

| SUS * | 40.35 | 48.99 | 49.77 | 55.56 | 48.93 | 49.52 |

| Perception of good healthcare quality * | 97.93 | 97.89 | 97.27 | 98.59 | 96.88 | 97.63 |

| Healthcare effectiveness ‡ | 96.15 | 96.20 | 96.37 | 99.50 | 97.94 | 97.43 |

| 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.04 | |

| Health issue severity * | 0.67 | 0.80 | 0.86 | 0.47 | 1.83 | 0.99 |

| Marginal Predictions—PHC Quality | 1998 | 2003 | 2008 | 2013 | 2019 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public sector funding | Margin | 0.965 | 0.963 | 0.954 | 0.981 | 0.948 |

| SE | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.003 | |

| Private sector funding | Margin | 0.988 | 0.993 | 0.989 | 0.993 | 0.995 |

| SE | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | |

| Pairwise comparison | Contrast | −0.023 * | −0.030 * | −0.035 * | −0.012 * | −0.047 * |

| SE | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.003 | |

| Public facility | Margin | 0.964 | 0.963 | 0.954 | 0.981 | 0.948 |

| SE | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.003 | |

| Private facility | Margin | 0.992 | 0.994 | 0.990 | 0.992 | 0.995 |

| SE | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | |

| Pairwise comparison | Contrast | −0.028 * | −0.031 * | −0.036 * | −0.011 * | −0.047 * |

| SE | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.003 | |

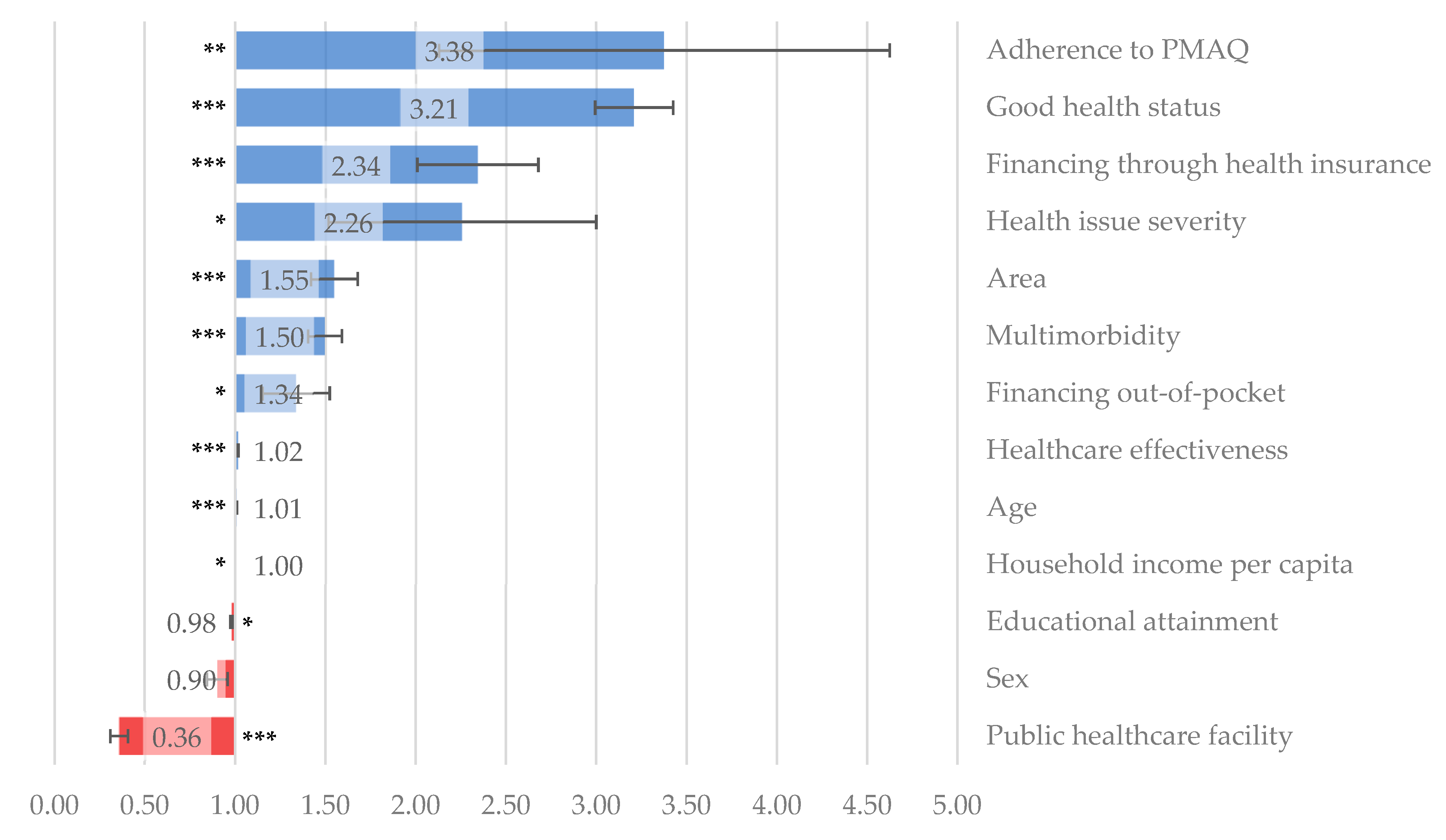

| Perception of Good Healthcare Quality | OR | SE | Sig. | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthcare effectiveness | (%) | 1.017 | 0.002 | *** | 1.013; 1.021 |

| Adherence to PMAQ-AB | (yes = 1) | 3.376 | 1.249 | ** | 1.635; 6.971 |

| Sex | (fem = 1) | 0.901 | 0.058 | 0.794; 1.022 | |

| Age | (years) | 1.008 | 0.002 | *** | 1.004; 1.012 |

| Educational attainment | (years) | 0.981 | 0.008 | * | 0.965; 0.997 |

| Good health status | (yes = 1) | 3.209 | 0.216 | *** | 2.813; 3.661 |

| Multimorbidity | (yes = 1) | 1.497 | 0.094 | *** | 1.323; 1.694 |

| Health issue severity | (yes = 1) | 2.258 | 0.742 | * | 1.185; 4.301 |

| Public healthcare facility | (yes = 1) | 0.358 | 0.048 | *** | 0.275; 0.467 |

| Healthcare financed through health insurance | (yes = 1) | 2.344 | 0.335 | *** | 1.772; 3.102 |

| Healthcare financed out of pocket | (yes = 1) | 1.337 | 0.186 | * | 1.018; 1.757 |

| Household income per capita | (yes = 1) | 1.000 | 0.000 | * | 1.000; 1.000 |

| Area | (rural = 1) | 1.549 | 0.130 | *** | 1.314; 1.826 |

| Area under ROC curve | 0.7694 | ||||

| (95% CI) | (0.7614; 0.7774) | ||||

| Hosmer–Lemeshow χ2 | 1564.48 | ||||

| Prob > χ2 | 0.1133 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Antiga, M.L.d.O.C.; Freitas, B.L.; Brizan-St. Martin, R.; La Foucade, A.; Sarti, F.M. Determinants of Patients’ Perception of Primary Healthcare Quality: Empirical Analysis in the Brazilian Health System. Healthcare 2025, 13, 857. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13080857

Antiga MLdOC, Freitas BL, Brizan-St. Martin R, La Foucade A, Sarti FM. Determinants of Patients’ Perception of Primary Healthcare Quality: Empirical Analysis in the Brazilian Health System. Healthcare. 2025; 13(8):857. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13080857

Chicago/Turabian StyleAntiga, Maria Luisa de Oliveira Collino, Bruna Leão Freitas, Roxanne Brizan-St. Martin, Althea La Foucade, and Flavia Mori Sarti. 2025. "Determinants of Patients’ Perception of Primary Healthcare Quality: Empirical Analysis in the Brazilian Health System" Healthcare 13, no. 8: 857. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13080857

APA StyleAntiga, M. L. d. O. C., Freitas, B. L., Brizan-St. Martin, R., La Foucade, A., & Sarti, F. M. (2025). Determinants of Patients’ Perception of Primary Healthcare Quality: Empirical Analysis in the Brazilian Health System. Healthcare, 13(8), 857. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13080857