Knowledge, Perceptions, and Practices of Primary Care Physicians on HIV and PrEP: Challenges and Principles of PrEP Use

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

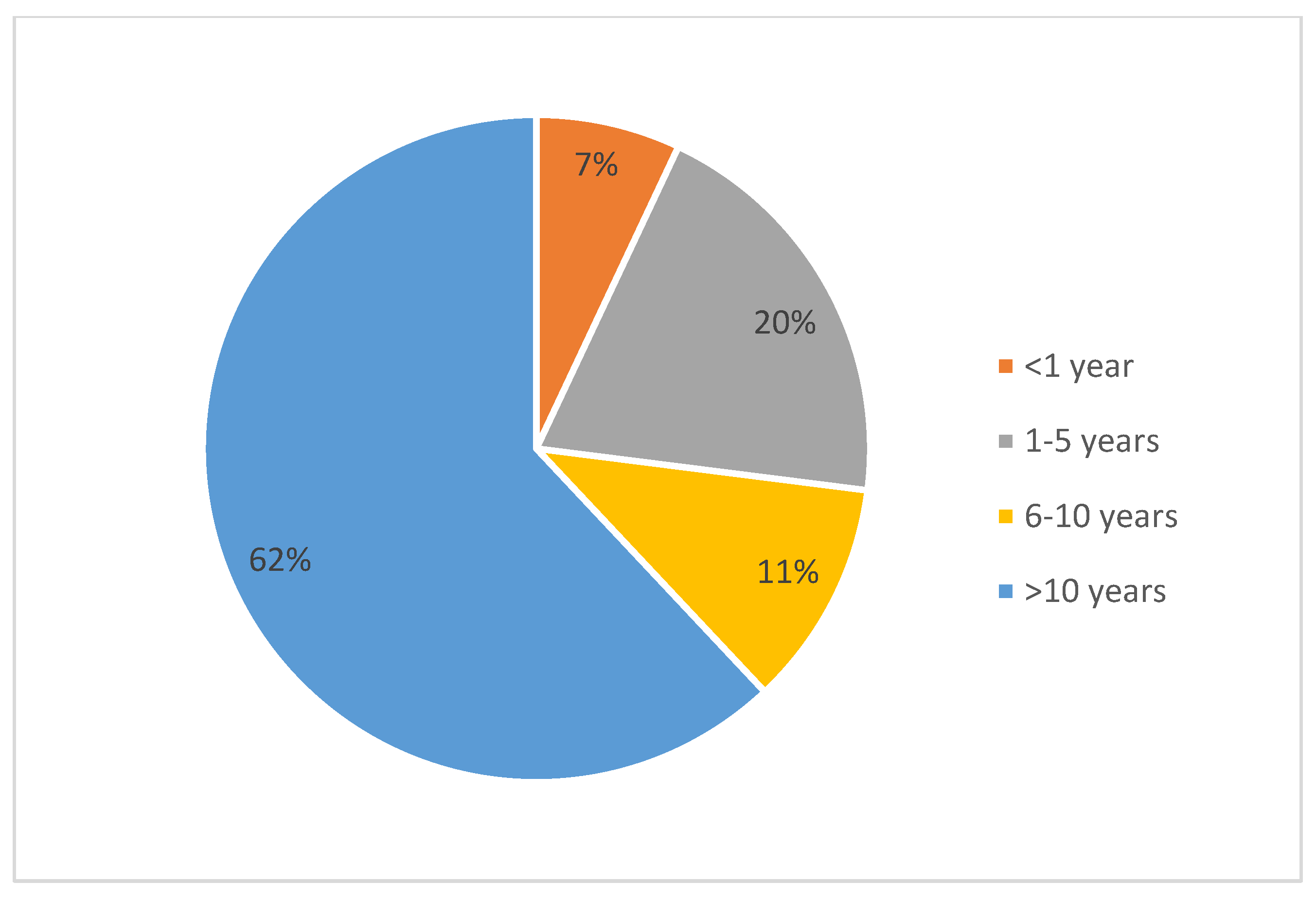

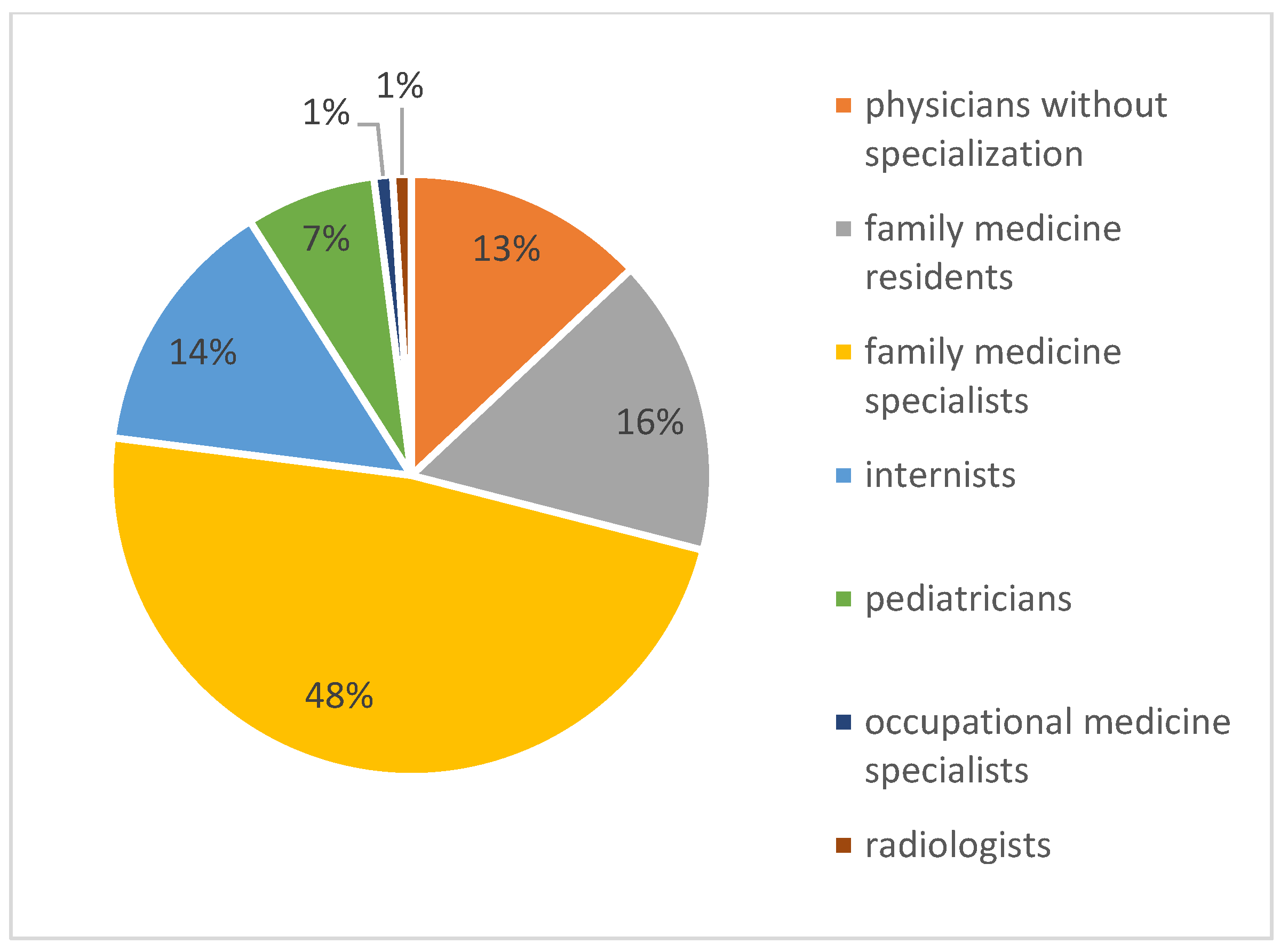

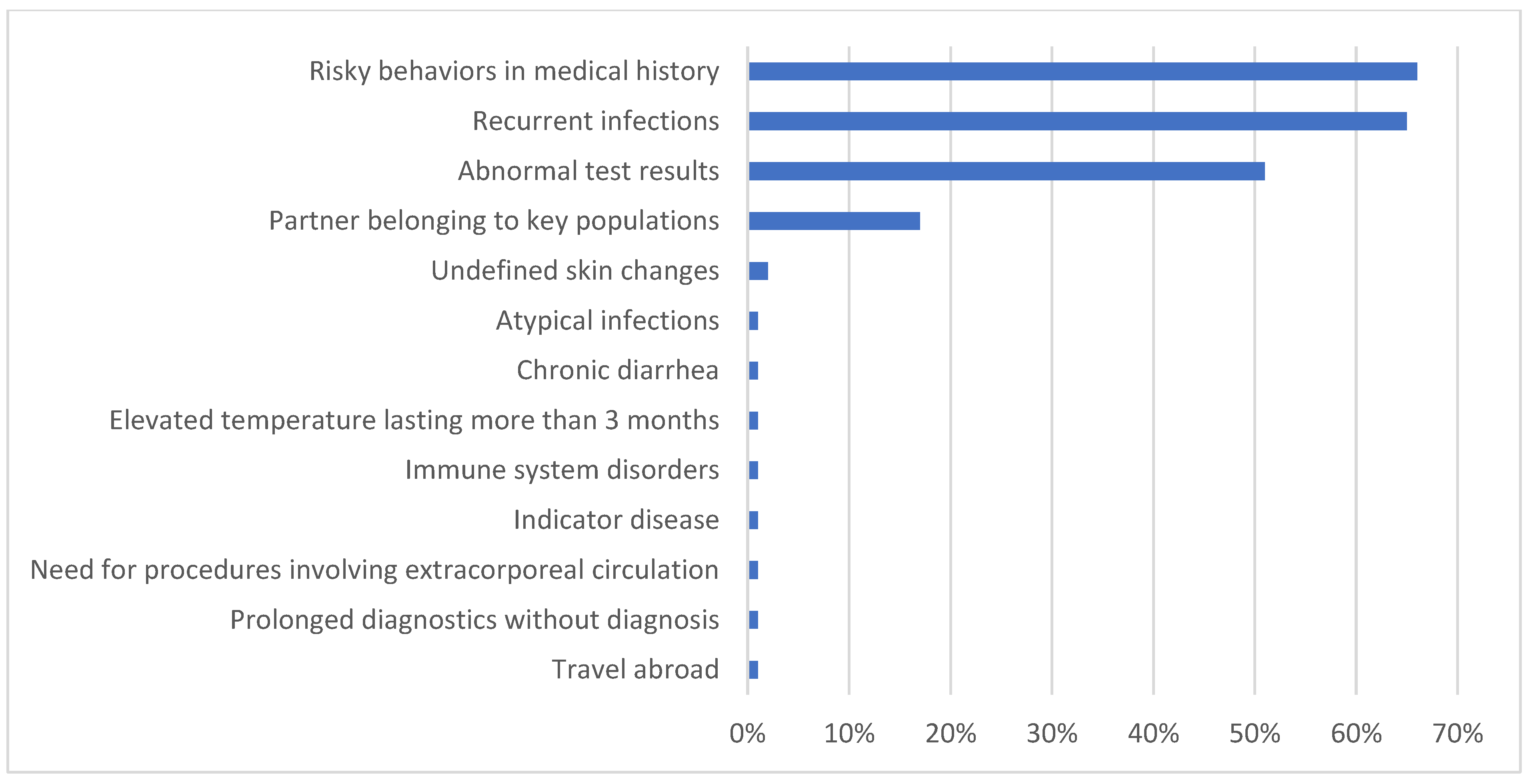

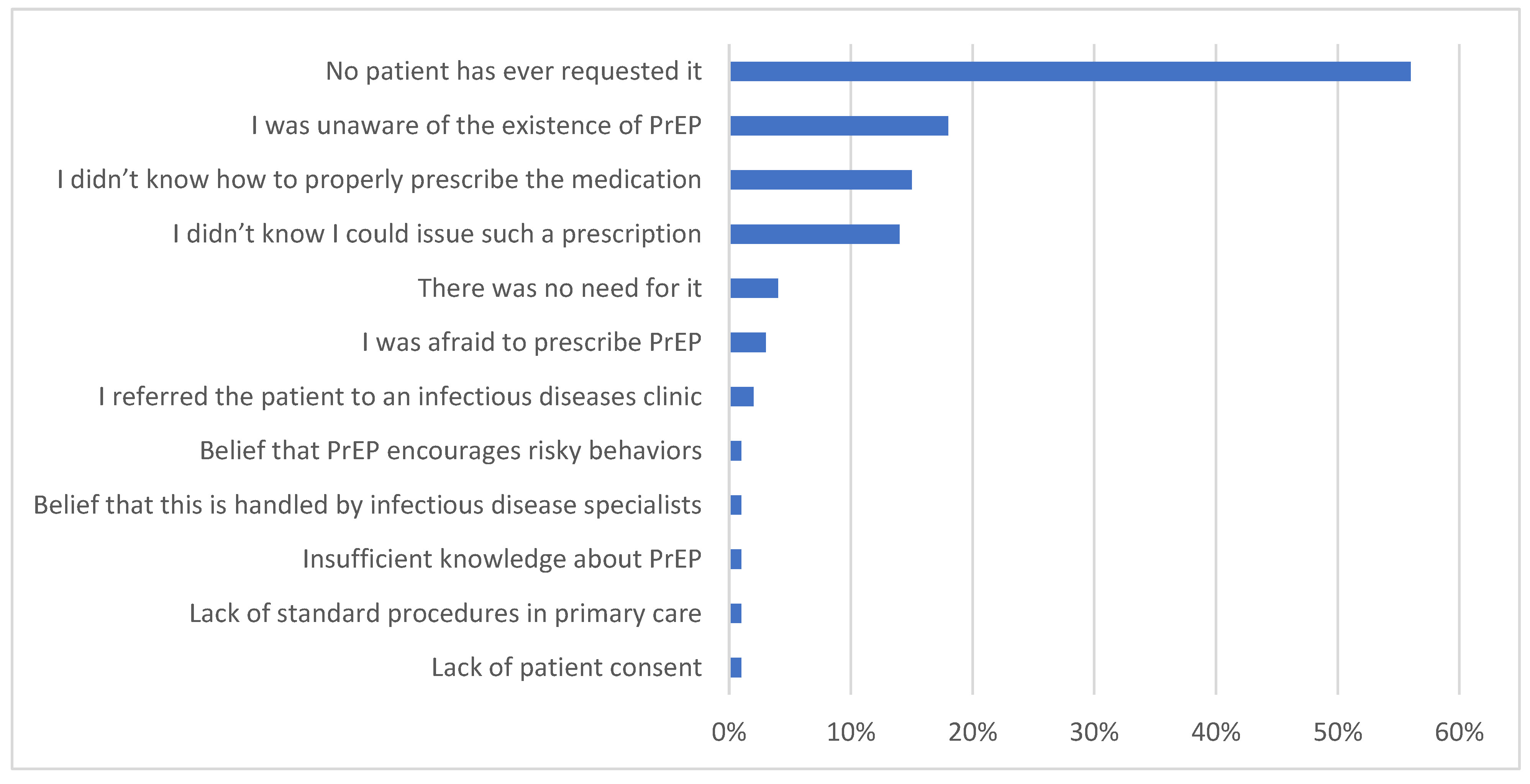

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Recommendations for Primary Care Physicians

6. Limitations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Departament Analiz i Innowacji. NFZ o Zdrowiu HIV AIDS; Departament Analiz i Innowacji: Warsaw, Poland, 2022; ISBN 978-83-956980-9-5. [Google Scholar]

- Kozieł, A.; Cieślik, A.; Janek, Ł.; Szymczak, A.; Domański, I.; Knysz, B.; Szetela, B. Changes in the HIV Epidemic in Lower Silesia, Poland, Between 2010 and 2020: The Characteristics of the Key Populations. Viruses 2024, 16, 1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antinori, A.; Coenen, T.; Costagiola, D.; Dedes, N.; Ellefson, M.; Gatell, J.; Girardi, E.; Johnson, M.; Kirk, O.; Lundgren, J.; et al. Late Presentation of HIV Infection: A Consensus Definition. HIV Med. 2011, 12, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz-Pinto, I.; Gorgulho, A.; Esteves, C.; Guimarães, M.; Castro, V.; Carrodeguas, A.; Medina, D. Increasing HIV Early Diagnosis by Implementing an Automated Screening Strategy in Emergency Departments. HIV Med. 2022, 23, 1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boffin, N.; Moreels, S.; Deblonde, J.; Van Casteren, V. Four Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs) in Belgian General Practice: First Results (2013–2014) of a Nationwide Continuing Surveillance Study. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e012118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kall, M.M.; Smith, R.D.; Delpech, V.C. Late HIV Diagnosis in Europe: A Call for Increased Testing and Awareness Among General Practitioners. Eur. J. Gen. Pract. 2012, 18, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leber, W.; Anderson, J.; Griffiths, C. HIV Testing in Europe: How Can Primary Care Contribute? Sex. Transm. Infect. 2015, 91, 464–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R. Time to Improve HIV Testing and Recording of HIV Diagnosis in UK Primary Care. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2009, 85, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bergen, J.E.A.M. Commentary on: Late HIV Diagnoses in Europe: A Call for Increased Testing and Awareness Among General Practitioners. Eur. J. Gen. Pract. 2012, 18, 133–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gbadamosi, S.O.; Trepka, M.J.; Dawit, R.; Jebai, R.; Sheehan, D.M. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis to Estimate the Time from HIV Infection to Diagnosis for People with HIV. AIDS Rev. 2022, 24, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, F.M.; Johnson, A.M.; Nazroo, J.; Ainsworth, J.; Anderson, J.; Fakoya, A.; Fakoya, I.; Hughes, A.; Jungmann, E.; Sadiq, S.T.; et al. Missed Opportunities for Earlier HIV Diagnosis within Primary and Secondary Healthcare Settings in the UK. AIDS 2008, 22, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champenois, K.; Cousien, A.; Cuzin, L.; Le Vu, S.; Deuffic-Burban, S.; Lanoy, E.; Lacombe, K.; Patey, O.; Béchu, P.; Calvez, M.; et al. Missed Opportunities for HIV Testing in Newly-HIV-Diagnosed Patients, a Cross Sectional Study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2013, 13, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szetela, B. Ulotka Dotycząca Profilaktyki Przedekspozycyjnej (Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis—PrEP); Krajowe Centrum Ds. AIDS: Warszawa, Poland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Preventing HIV with PrEP|HIV|CDC. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/prevention/prep.html (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis to Prevent HIV Among MSM in Europe. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/news-events/pre-exposure-prophylaxis-prevent-hiv-among-msm-europe (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Global HIV Programme. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/global-hiv-hepatitis-and-stis-programmes/hiv/prevention/pre-exposure-prophylaxis (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Global HIV, Hepatitis and STIs Programmes. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/global-hiv-hepatitis-and-stis-programmes/strategies/global-health-sector-strategies (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Global State of PrEP. Available online: https://www.who.int/groups/global-prep-network/global-state-of-prep (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Sammons, M.K.; Gaskins, M.; Kutscha, F.; Nast, A.; Werner, R.N. HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP): Knowledge, Attitudes and Counseling Practices among Physicians in Germany—A Cross-Sectional Survey. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0250895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, R.; Schmidt, A.J.; Pharris, A.; Azad, Y.; Brown, A.E.; Weatherburn, P.; Hickson, F.; Delpech, V.; Noori, T.; Bani, R.; et al. Estimating the “PrEP Gap”: How Implementation and Access to PrEP Differ between Countries in Europe and Central Asia in 2019. Eurosurveillance 2019, 24, 1900598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogowska-Szadkowska, D.; Chlabicz, S. Does the Poor HIV/AIDS Knowledge among Medical Students May Contribute to Late Diagnosis? Przegl. Epidemiol. 2010, 64, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rogowska-Szadkowska, D.; Strumiło, J.; Chlabicz, S. Knowledge of Family Medicine Trainers Concerning HIV/AIDS—Pilot Study. Przegl. Epidemiol. 2017, 71, 629–637. [Google Scholar]

- Tominski, D.; Katchanov, J.; Driesch, D.; Daley, M.B.; Liedtke, A.; Schneider, A.; Slevogt, H.; Arastéh, K.; Stocker, H. The Late-Presenting HIV-Infected Patient 30 Years after the Introduction of HIV Testing: Spectrum of Opportunistic Diseases and Missed Opportunities for Early Diagnosis. HIV Med. 2017, 18, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deblonde, J.; Van Beckhoven, D.; Loos, J.; Boffin, N.; Sasse, A.; Nöstlinger, C.; Supervie, V. HIV Testing within General Practices in Europe: A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayment, M.; Thornton, A.; Mandalia, S.; Elam, G.; Atkins, M.; Jones, R.; Nardone, A.; Roberts, P.; Tenant-Flowers, M.; Anderson, J.; et al. HIV Testing in Non-Traditional Settings--the HINTS Study: A Multi-Centre Observational Study of Feasibility and Acceptability. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e39530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chipidza, F.E.; Wallwork, R.S.; Stern, T.A. Impact of the Doctor-Patient Relationship. Prim. Care Companion CNS Disord. 2015, 17, 27354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabety, A. The Value of Relationships in Healthcare. J. Public Econ. 2023, 225, 104927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, K.E.; Hemmige, V.; Kallen, M.A.; Street, R.L.; Giordano, T.P.; Arya, M. Whether Patients Want It or Not, Physician Recommendations Will Convince Them to Accept HIV Testing. J. Int. Assoc. Provid. AIDS Care 2018, 17, 2325957417752258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- KFF. Survey of Americans on HIV/AIDS 2012; KFF: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, E.K.; Thorpe, L.; Myers, J.E.; Nash, D. Healthcare-Related Correlates of Recent HIV Testing in New York City. Prev. Med. 2012, 54, 440–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Sadler, K.E.; Low, N.; Mercer, C.H.; Sutcliffe, L.J.; Islam, M.A.; Shafi, S.; Brook, G.M.; Maguire, H.; Horner, P.J.; Cassell, J.A. Testing for Sexually Transmitted Infections in General Practice: Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Biagio, A.; Riccardi, N.; Signori, A.; Maserati, R.; Nozza, S.; Gori, A.; Bonora, S.; Borderi, M.; Ripamonti, D.; Rossi, M.C.; et al. PrEP in Italy: The Time May Be Ripe but Who’s Paying the Bill? A Nationwide Survey on Physicians’ Attitudes towards Using Antiretrovirals to Prevent HIV Infection. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0181433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, J.L.; Petroll, A.E. Factors Related to Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Prescription by U.S. Primary Care Physicians. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2017, 52, e165–e172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuamah Eshun, S.; Mwinilanaa Tampah-Naah, A.; Udor, R.; Addae, D. Awareness and Willingness to Use Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) and Post-Exposure Prophylaxis (PEP) among Sexually Active Adults in Ghana. HIV AIDS Rev. 2023, 22, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czy Lekarz Rodzinny Może Przepisać PrEP? Available online: https://podyplomie.pl/hiv/posts/1264.czy-lekarz-rodzinny-moze-przepisac-prep (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Czy Lekarz Rodzinny Może Przepisywać PrEP Czy Lepiej Jest Kierować Pacjenta Do Ośrodka Specjalistycznego?—Wywiady—AIDS—Medycyna Praktyczna Dla Lekarzy. Available online: https://www.mp.pl/aids/wywiady/247318,czy-lekarz-rodzinny-moze-przepisywac-prep-czy-lepiej-jest-kierowac-pacjenta-do-osrodka-specjalistycznego (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Agencja Oceny Technologii Medycznych i Taryfikacji. Leczenie Antyretrowirusowe Osób Żyjących z Wirusem HIV; Agencja Oceny Technologii Medycznych i Taryfikacji: Warszawa, Poland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jarrín, I.; Rava, M.; Del Romero Raposo, J.; Rivero, A.; Del Romero Guerrero, J.; De Lagarde, M.; Sanz, J.M.; Navarro, G.; Dalmau, D.; Blanco, J.R.; et al. Life Expectancy of People with HIV on Antiretroviral Therapy in Spain. AIDS 2024, 38, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trickey, A.; Sabin, C.A.; Burkholder, G.; Crane, H.; d’Arminio Monforte, A.; Egger, M.; Gill, M.J.; Grabar, S.; Guest, J.L.; Jarrin, I.; et al. Life Expectancy after 2015 of Adults with HIV on Long-Term Antiretroviral Therapy in Europe and North America: A Collaborative Analysis of Cohort Studies. Lancet HIV 2023, 10, e295–e307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piotr, G. (Ed.) Interna Szczeklika 2022; Medycyna Praktyczna: Kraków, Poland, 2022; ISBN 978-83-7430-669-0. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A.; Chidambaram, Y.; Dhas, C.J.; Abilash, N.; Alagesan, M. Clinical Profile and Outcomes Analysis of HIV Infection. HIV AIDS Rev. 2024, 23, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, S.; Farahani, A.; Zebardast, A.; Dowran, R.; Zandi, M.; Rafat, Z.; Sasani, E.; Zarandi, B.; Taha, M.; Fallahy, P.; et al. Human Immunodeficiency Virus and Candida Albicans Co-Infection in Iran: A Systematic Review. HIV AIDS Rev. 2023, 22, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuttikul, C.; Thanawuth, N.; Rojpibulsatit, M.; Pattharachayakul, S. Time to Antiretroviral Therapy Initiation in HIV-Positive Patients with Opportunistic Infections/AIDS-Defining Illness in Southern Thailand: A Prospective Cohort Study. HIV AIDS Rev. 2024, 23, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, B.R. Acute and Recent HIV Infection. Available online: https://www.hiv.uw.edu/go/screening-diagnosis/acute-recent-early-hiv/core-concept/all#page-title (accessed on 28 December 2023).

- Recommendations of an Expert Group Appointed by the Polish Gynaecological Society on Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV. Ginekol. Pol. 2009, 80, 390–394.

- Parczewski, M.; Witak-Jędra, M.; Aksak-Wąs, B.; Ciechanowski, P. ZASADY OPIEKI NAD OSOBAMI ŻYJĄCYMI Z HIV; Zalecenia PTN AIDS: Warszawa, Poland, 2024; ISBN 978-83-67471-26-8. [Google Scholar]

- Murchu, E.O.; Marshall, L.; Teljeur, C.; Harrington, P.; Hayes, C.; Moran, P.; Ryan, M. Oral Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) to Prevent HIV: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Clinical Effectiveness, Safety, Adherence and Risk Compensation in All Populations. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e048478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unigwe, I.F.; Goodin, A.; Lo-Ciganic, W.H.; Cook, R.L.; Janelle, J.; Park, H. Trajectories of Adherence to Oral Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis and Risks of HIV and Sexually Transmitted Infections. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2024, 11, ofae569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

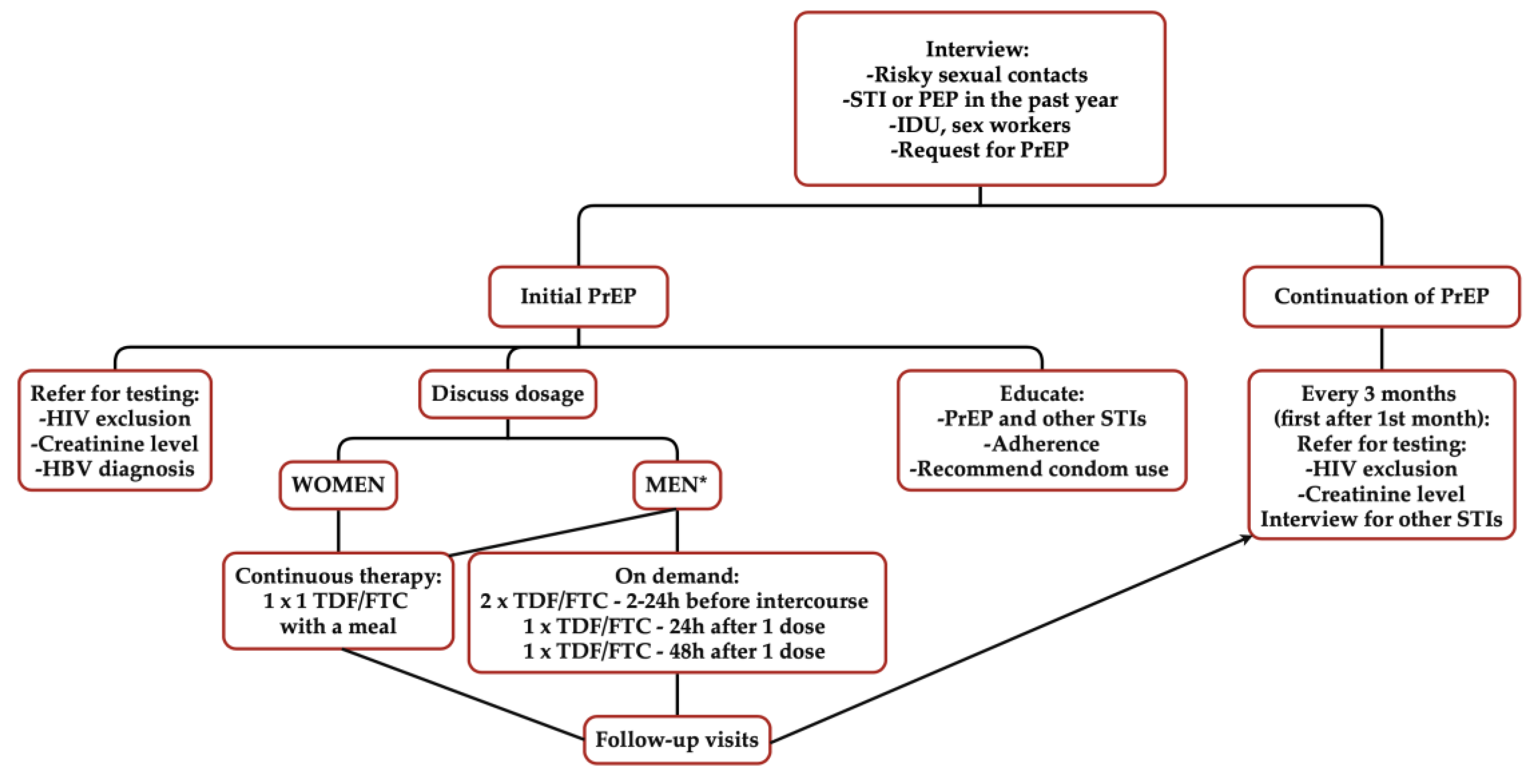

| Before Prescribing PrEP: | During PrEP Use (1-Month Follow-Up, Subsequent Visits Every 3 Months): |

|---|---|

The following should be applied:

| The following should be applied:

|

Additionally, it is recommended to pursue the following:

| |

| During each visit, it is recommended to provide education, emphasise the importance of condom use, and stress adherence. | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kozieł, A.; Domański, I.; Kuderska, N.; Szetela, B.; Szymczak, A.; Knysz, B. Knowledge, Perceptions, and Practices of Primary Care Physicians on HIV and PrEP: Challenges and Principles of PrEP Use. Healthcare 2025, 13, 854. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13080854

Kozieł A, Domański I, Kuderska N, Szetela B, Szymczak A, Knysz B. Knowledge, Perceptions, and Practices of Primary Care Physicians on HIV and PrEP: Challenges and Principles of PrEP Use. Healthcare. 2025; 13(8):854. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13080854

Chicago/Turabian StyleKozieł, Aleksandra, Igor Domański, Natalia Kuderska, Bartosz Szetela, Aleksandra Szymczak, and Brygida Knysz. 2025. "Knowledge, Perceptions, and Practices of Primary Care Physicians on HIV and PrEP: Challenges and Principles of PrEP Use" Healthcare 13, no. 8: 854. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13080854

APA StyleKozieł, A., Domański, I., Kuderska, N., Szetela, B., Szymczak, A., & Knysz, B. (2025). Knowledge, Perceptions, and Practices of Primary Care Physicians on HIV and PrEP: Challenges and Principles of PrEP Use. Healthcare, 13(8), 854. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13080854