Analysis of Program Activities to Develop Forest Therapy Programs for Improving Mental Health: Focusing on Cases in Republic of Korea

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Program Search

2.2.1. Research Literature

2.2.2. Program Casebook

2.2.3. Forest Field Program

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Data Extraction

3. Results

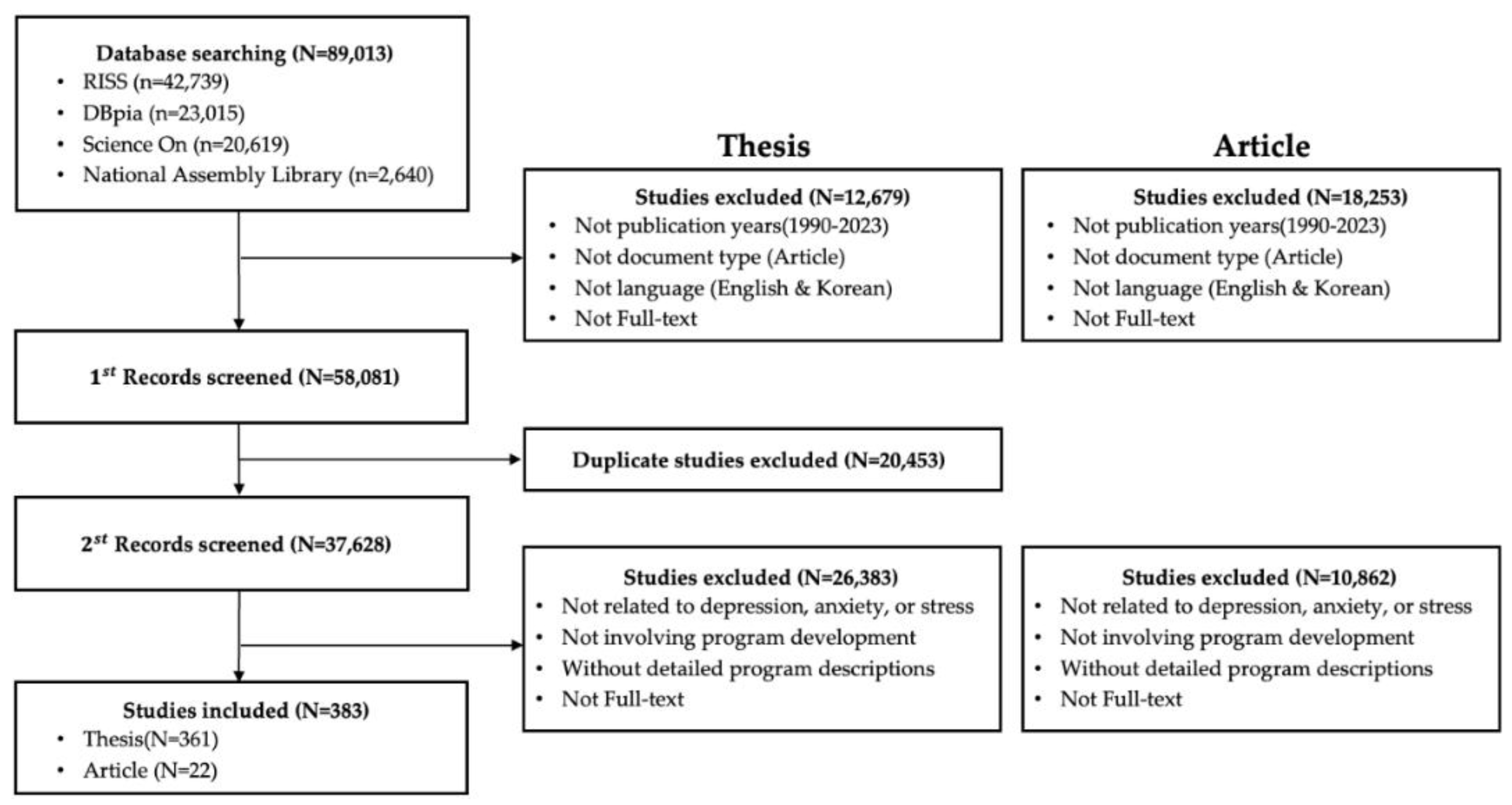

3.1. Search Results

Literature Search

3.2. Program General Characteristics

3.3. Formal Characteristics of Programs

3.4. Program Activity Content

3.4.1. Purpose-Driven Activities

3.4.2. Practical Activities

3.5. Forest Environment Characteristics

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Category | Keywords |

|---|---|

| Intervention | “forest*” OR “forest exposure” OR “forest bathing” OR “forest healing” OR “forest therap*” OR “shinrin-yoku” OR “urban forest*” OR “green space” OR “greenspace” OR “urban green*” OR “green exercise” OR “tree*” OR “garden*” OR “park” OR “parks” OR “landscape*” OR “horticulture*” OR “horticultural*” OR “wood*” OR “natural environment*” OR “green infrastructure*” OR “greenness” OR “nature-based” OR “outdoor*” OR “recreation” OR “forest experience” OR “forest activity” OR “forest adventure” OR “nature” OR “natural activity” OR “forest walking” OR “Hospitals” OR “Centers” OR “Therap*” OR “Treatment” OR “Mentali*” OR “art therap*” OR “experiment” OR “service” OR “hydro therapy” OR “training” OR “Exercise” OR “Recovery” OR “intervention” |

| Intervention | “program” |

| Effects | “depress*” OR “depression” OR “depressive disorder” OR “anxiety*” OR “anxiety disorder” OR “Hamilton Rating Scale s for Depression” OR “Hamilton Depression Rating Scale” OR “Beck Depression Inventory” OR “Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale” OR “Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale” OR “ZungSelf-Rating Depression Scale” OR “Stress” OR “cortisol” OR “stress response index” OR “mental health” |

| Effects | “Effect” OR “Development” OR “Impact” |

| Category | Keywords |

|---|---|

| Intervention | “숲” OR “산림” OR “자연” OR “산림치유” OR “도시숲” OR “치유” OR “체험” OR “숲놀이” OR “삼림욕” OR “테라피” OR “활동” OR “경험” OR “요법” OR “산림운동” OR “숲치유” OR “산림교육” OR “경관” OR “산림휴양” OR “센터” OR “치료 “ OR “환자” OR “중재” OR “비약물적중재” OR “원예” OR “치유정원” OR “식물재배” OR “개입” OR “미술치료” OR “상 담” OR “음악치료” OR “이야기치료” OR “처치” OR “행동” OR “집단프로그램” OR “사업” OR “서비스” OR “심리” OR “ 자조모임” OR “지역사회통합돌봄” OR “신체활동” OR “재활운동” |

| Intervention | “프로그램” |

| Effects | “우울” OR “불안” OR “스트레스” OR “질환자” OR “정신보건” OR “정신건강” |

| Effects | “영향” OR “효과” OR “개발” |

References

- Teh, C.K.; Ngo, C.W.; Vellasamy, R.; Suresh, K. Depression, anxiety and stress among undergraduate students: A cross-sectional study. Open J. Epidemiol. 2015, 5, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Depressive Disorder (Depression). Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression (accessed on 31 March 2023).

- Ministry of Health and Welfare. The 2nd Basic Plan for Mental Health and Welfare (2021–2025); Ministry of Health and Welfare: Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yeon, P.; Jeon, J.; Jung, M.; Min, G.; Kim, G.; Han, K.; Shin, M.; Jo, S.; Kim, J.; Shin, W. Effect of forest therapy on depression and anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorman, J.M. Comorbid depression and anxiety spectrum disorders. Depress. Anxiety 1996, 4, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, A.J.; Leonard, H.; Swedo, S.E. Current knowledge of medications for the treatment of childhood anxiety disorders. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1995, 34, 976–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center for Mental Health. Korean Mental Health Information Portal. Available online: https://www.mentalhealth.go.kr/portal/disease/diseaseDetail.do?dissId=31&srCodeNm=불면장애 (accessed on 8 May 2020).

- National Center for Mental Health. Korean Mental Health Information Portal. Available online: https://www.mentalhealth.go.kr/portal/disease/diseaseDetail.do?dissId=30&srCodeNm=스트레스 (accessed on 1 June 2020).

- Kim, I.; Lee, J.; Park, S. The relationship between stress, inflammation, and depression. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsuddin, K.; Fadzil, F.; Ismail, W.S.W.; Shah, S.A.; Omar, K.; Muhammad, N.A.; Jaffar, A.; Ismail, A.; Mahadevan, R. Correlates of depression, anxiety and stress among Malaysian university students. Asian J. Psychiatry 2013, 6, 318–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammen, C. Stress and depression. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 1, 293–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Sun, W.; Sun, X.; Sun, J.; Yang, D.; Jia, B.; Yuan, B. Effects of mindfulness meditation on anxiety, depression, stress, and mindfulness in nursing students: A meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front. Nurs. 2020, 7, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komariah, M.; Ibrahim, K.; Pahria, T.; Rahayuwati, L.; Somantri, I. Effect of mindfulness breathing meditation on depression, anxiety, and stress: A randomized controlled trial among university students. Healthcare 2022, 10, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, S.A.; Cunningham, K.; Bloch, R.M. Depression and anxiety disorders: Benefits of exercise, yoga, and meditation. Am. Fam. Physician 2019, 99, 620–627. [Google Scholar]

- Lemay, V.; Hoolahan, J.; Buchanan, A. Impact of a yoga and meditation intervention on students’ stress and anxiety levels. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2019, 83, 7001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salmon, P. Effects of physical exercise on anxiety, depression, and sensitivity to stress: A unifying theory. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2001, 21, 33–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carek, P.J.; Laibstain, S.E.; Carek, S.M. Exercise for the treatment of depression and anxiety. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 2011, 41, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bentley, T.G.; D’Andrea-Penna, G.; Rakic, M.; Arce, N.; LaFaille, M.; Berman, R.; Cooley, K.; Sprimont, P. Breathing practices for stress and anxiety reduction: Conceptual framework of implementation guidelines based on a systematic review of the published literature. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korea Forest Service. Forestry Culture and Recreation Act, Article 2, Paragraph 4. Available online: https://elaw.klri.re.kr/kor_service/lawView.do?hseq=27993&lang=ENG (accessed on 20 June 2023).

- Jeong, J.H.; Kim, K.W.; Moon, C.Y.; Kim, J.J.; Kim, T.I. A Study on the Integration Plan of National Welfare System through Forest Welfare Services: Focusing on the Concept Derivation of Forest Welfare. J. Korean For. Rec. Sci. 2016, 20, 43–55. [Google Scholar]

- Chae, Y.R.; Kim, J.H.; Kang, H.W. A review of forest healing therapy applied to Korean adults. J. Korean Biol. Nurs. Sci. 2018, 20, 89–101. [Google Scholar]

- Song, J.H.; Shin, W.S.; Yeon, P.S.; Kim, Y.S.; Cho, Y.M.; Kim, J.Y.; Son, S.A.; Shin, K.H. Effects of forest healing camps on the psychological stability of youth victims of school violence. J. Korean For. Soc. 2012, 16, 109–115. [Google Scholar]

- Chun, M.H.; Chang, M.C.; Lee, S. The effects of forest therapy on depression and anxiety in patients with chronic stroke. Int. J. Neurosci. 2017, 127, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.; Choi, H.; Bang, K.; Kim, S.; Song, M.; Lee, B. Effects of forest therapy on depressive symptoms among adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Feng, L.; Duan, W. The impact of forest therapy programs on stress reduction: A systematic review from 2009–2018. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 14, 1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.H. Analysis of preferences for program development in forest healing programs. J. Korean Environ. Ecol. 2016, 30, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, Y.R.; Lee, S.H. A systematic literature review on forest healing programs for adult patients. J. Korean Biol. Nurs. Sci. 2020, 22, 189–201. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.H.; Chun, S.M.; Kim, S.K. A meta-analysis of the effects of group therapy programs for reducing depression. Dev. Disabil. Res. 2014, 18, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Peral, P.; Conejo-Ceron, S.; Rubio-Valera, M.; Fernandez, A.; Navas-Campana, D.; Rodriguez-Morejon, A.; Motrico, E.; Rigabert, A.; de Dios Luna, J.; Martin-Perez, C. Effectiveness of psychological and/or educational interventions in the prevention of anxiety: A systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. JAMA Psychiatry 2017, 74, 1021–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, Y.S. The Effects of a Positive Psychology Program on Depression, Self-Esteem, and Hope in Adults with Depression. Master’s Thesis, Jeju National University, Jeju, Republic of Korea, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sung, M.H. The Effects of a Positive Psychology Therapy Program on Depression, Self-Esteem, and School Adjustment of Elementary School Students with Depressive Tendencies. Master’s Thesis, Kyungsung University, Busan, Republic of Korea, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.H. The Effects of Group Art Therapy on Depression in Elderly Attending Daycare Centers. Master’s Thesis, Dongguk University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, O.K. The Effects of Participation in an Art Therapy Program on Depression and Happiness in Elderly Residents of Nursing Homes. Master’s Thesis, Kyung Hee University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, E.K. The Effects of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy on Depression and Suicidal Ideation in Adolescents. Master’s Thesis, Kangwon National University, Chuncheon, Republic of Korea, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, N.S. The Effects of a Cognitive-Behavioral Group Counseling Program on Body Image, Self-Esteem, and Depression of Obese Female High School Students. Master’s Thesis, Kookmin University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.J. The Effects of an Acceptance and Commitment Therapy Program on Depression, Job Burnout, and Self-Efficacy of Mobile Phone Salespersons. Master’s Thesis, Kyungsung University, Busan, Republic of Korea, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.Y. Development and Effects of an Acceptance and Commitment Therapy-Based Group Art Program for Elderly with Depressive Tendency. Ph.D. Thesis, Daegu Catholic University, Gyeongsan, Republic of Korea, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.M. The Effects of Positive Psychology Therapy on Optimism, Stress, and Psychological Well-Being of Depressive Middle School Students. Master’s Thesis, Kyungsung University, Busan, Republic of Korea, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, E.J. The Effects of Positive Psychology Group Counseling on School Adaptation Stress Reduction in Newly Admitted Elementary School Students. Master’s Thesis, Daegu National University of Education, Daegu, Republic of Korea, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, E.J. A Study on the Effects of a Bibliotherapy Program on Stress Reduction in the Elderly. Ph.D. Thesis, Sangmyung University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Shim, H.M. The Effects of a Group Bibliotherapy Program on Stress Levels, Somatic Symptoms, and Empathy in Gifted Children. Master’s Thesis, Myongji University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, J.H. The Effects of a Mindfulness Program on Self-Esteem and Stress in Children. Master’s Thesis, Jinju National University of Education, Jinju, Republic of Korea, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, H.M. The Effects of a Mindfulness Meditation Program on Stress Responses and Power of Psychiatric Inpatients. Master’s Thesis, Eulji University, Daejeon, Republic of Korea, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, K.S. The Effects of a Yoga Activity Program on Stress and Self-Concept of Preschool Children. Master’s Thesis, Gwangju University, Gwangju, Republic of Korea, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.O. The Effects of a Yoga Meditation Program on Stress Responses in Middle-Aged Women. Master’s Thesis, Jeju National University, Jeju, Republic of Korea, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, U.H. The Effects of an Art Therapy Program on Maladaptive Behaviors of Preschool Children. Master’s Thesis, Myongji University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, K.H. The Effects of a Mandala Group Art Therapy Program on Aggression and Anxiety of Elementary School Students. Master’s Thesis, Kyungsung University, Busan, Republic of Korea, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, M.J. The Effects of Group Counseling Integrating Meditation Training and Self-Growth Program on Self-Esteem, Self-Control, and Anxiety of Institutionalized Adolescents. Master’s Thesis, Jeonju University, Jeonju, Republic of Korea, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, Y.J. The Effects of Group Play Therapy Using Meditation on Anxiety and Self-Regulation Ability of Preschool Children. Master’s Thesis, Dongguk University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Koo, J.S. The Effects of a Self-Awareness-Centered Bibliotherapy Program on Anxiety and Aggression in Low-Income Adolescents. Master’s Thesis, Kyungpook National University, Daegu, Republic of Korea, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Schreiner, I.; Malcolm, J.P. The benefits of mindfulness meditation: Changes in emotional states of depression, anxiety, and stress. Behav. Chang. 2008, 25, 156–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breedvelt, J.J.; Amanvermez, Y.; Harrer, M.; Karyotaki, E.; Gilbody, S.; Bockting, C.L.; Cuijpers, P.; Ebert, D.D. The effects of meditation, yoga, and mindfulness on depression, anxiety, and stress in tertiary education students: A meta-analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y.S.; Kim, H.C.; Lee, C.J.; Jang, N.C.; Son, B.K. A Study of Effects of Sallimyok (Forest Therapy)-Based Mental Health Program on Depression and Psychological Stability. J. Korean Soc. Sch. Community Health Educ. 2014, 15, 55–65. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.G. The Effects of Forest Healing Programs on Physical and Mental Health and Life Satisfaction in Middle-Aged Women. Ph.D. Dissertation, Keimyung University, Daegu, Republic of Korea, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, J.Y. The Effects of Forest Healing on Stress, Fatigue, and Depression in Middle-Aged Women. Master’s Thesis, Wonkwang Digital University, Iksan, Republic of Korea, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.Y. Development and Effectiveness Verification of a Nature-Friendly Stress Management Program for University Students. Master’s Thesis, Daegu University, Gyeongsan, Republic of Korea, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.G. The Effectiveness of Self-Directed Forest Healing Programs. Ph.D. Dissertation, Chungbuk National University, Cheongju, Republic of Korea, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.J. The Effect of Forest Experience Activities on Daily Stress in 2-Year-Old Children. Master’s Thesis, Kongju National University, Gongju, Republic of Korea, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Y. The Effects of Forest Experience Activities on Stress and Aggression in Young Children. Master’s Thesis, Hansei University Graduate School of Social Welfare, Gunpo, Republic of Korea, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, K.A. The Effects of Forest Play Activities on Reducing Daily Stress in Young Children. Master’s Thesis, Seoul National University of Education Graduate School, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, J.S. The Effects of Forest Play Activities on Stress and Emotional Intelligence in Young Children. Master’s Thesis, Konkuk University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, S.A. The Effects of Nature Meditation Activities on Emotional Intelligence and Daily Stress in Young Children. Master’s Thesis, Dongguk University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, M.H. Changes in Sociality and Depression of Elementary School Students through School Forest Experience Activities during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Master’s Thesis, Chungnam National University Graduate School, Daejeon, Republic of Korea, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich, R.S.; Simons, R.F.; Losito, B.D.; Fiorito, E.; Miles, M.A.; Zelson, M. Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 1991, 11, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoltz, J.; Schaffer, C. Salutogenic affordances and sustainability: Multiple benefits with edible forest gardens in urban green spaces. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Field | Issuing Institution | Casebooks Title |

|---|---|---|

| Forestry | Korea Forest Welfare Institute |

|

| Healthcare | National Center for Mental Health |

|

| Therapeutic farming | National Institute of Agricultural Sciences |

|

| National Institute of Horticultural and Herbal Science |

|

| Characteristics | Category | Criteria | Frequency (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Korean | International | |||

| Year | Research literature | 1990~1999 | 4 (1.0) | 1 (5.0) |

| 2000~2004 | 21 (5.5) | - | ||

| 2005~2009 | 64 (16.7) | - | ||

| 2010~2014 | 121 (31.6) | 1 (5.0) | ||

| 2015~2019 | 108 (28.2) | 8 (40.0) | ||

| 2020~2023 | 65 (17.0) | 10 (50.0) | ||

| Program casebook and field programs | 2010~2014 | 1 (1.6) | - | |

| 2015~2019 | 17 (26.6) | |||

| 2020~2023 | 41 (64.1) | |||

| 2024 | 5 (7.8) | |||

| Discipline | Research literature | Psychology | 252 (65.8) | 6 (30.0) |

| Public health, healthcare, and nursing | 31 (8.1) | 10 (50.0) | ||

| Exercise and rehabilitation | 30 (7.8) | 3 (15.0) | ||

| Social welfare | 30 (7.8) | - | ||

| Horticulture and Therapeutic Farming | 24 (6.3) | 1 (5.0) | ||

| Forestry | 16 (4.2) | - | ||

| Program casebook and field programs | Healthcare | 15 (23.4) | - | |

| Therapeutic farming | 15 (23.4) | |||

| Forestry | 34 (53.1) | |||

| Mental disorder | Research literature | Depression | 152 (39.7) | 3 (15.0) |

| Anxiety | 34 (8.9) | 2 (10.0) | ||

| Stress | 119 (31.1) | 7 (35.0) | ||

| Depression, anxiety | 37 (9.7) | 2 (10.0) | ||

| Depression, stress | 31 (8.1) | 3 (15.0) | ||

| Anxiety, stress | 5 (1.3) | - | ||

| Depression, anxiety, and stress | 5 (1.3) | 3 (15.0) | ||

| Program casebook and field programs | Depression | 2 (3.1) | - | |

| Anxiety | - | |||

| Stress | 37 (57.8) | |||

| Depression, anxiety | 4 (6.3) | |||

| Depression, stress | 10 (15.6) | |||

| Anxiety, stress | 1 (1.6) | |||

| Depression, anxiety, and stress | 10 (15.6) | |||

| Characteristics | Category | Criteria | Frequency (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Korean | International | |||

| Age | Research literature | Infants and toddlers | 11 (2.9) | - |

| Children and adolescents | 164 (42.8) | 3 (15.0) | ||

| Young adults | 34 (8.9) | 5 (25.0) | ||

| Middle-aged adults | 49 (12.8) | 6 (30.0) | ||

| Older adults | 66 (17.2) | 1 (5.0) | ||

| Middle-aged to older adults | 19 (5) | 1 (5.0) | ||

| Young adults to middle-aged adults | 23 (6) | 1 (5.0) | ||

| Young adults to older adults | 7 (1.8) | 2 (10.0) | ||

| Not presented | 10 (2.6) | 1 (5.0) | ||

| Program casebook and field programs | Infants and toddlers | - | - | |

| Children and adolescents | 9 (14.1) | |||

| Young adults | 2 (3.1) | |||

| Middle-aged adults | 2 (3.1) | |||

| Older adults | 5 (7.8) | |||

| Infants and toddlers to children and adolescents | 1 (1.6) | |||

| Young adults to older adults | 20 (31.3) | |||

| Middle-aged to older adults | 1 (1.6) | |||

| All ages | 3 (4.70) | |||

| Not presented | 21 (32.8) | |||

| Gender | Research literature | Mixed | 236 (61.6) | 14 (70.0) |

| Male | 15 (3.9) | - | ||

| Female | 103 (26.9) | 4 (20.0) | ||

| Not presented | 29 (7.6) | 2 (10) | ||

| Program casebook and field programs | Mixed | 11 (17.2) | - | |

| Male | - | |||

| Female | - | |||

| Not presented | 53 (82.8) | |||

| Sessions | Research literature | <5 sessions | 12 (3.1) | 1 (5.0) |

| 5–10 sessions | 164 (42.8) | 11 (55.0) | ||

| 11–20 sessions | 186 (48.7) | 1 (5.0) | ||

| 21–30 sessions | 9 (2.3) | 3 (15.0) | ||

| ≥31 sessions | 5 (1.3) | 3 (15.0) | ||

| Not presented | 7 (1.8) | 1 (5.0) | ||

| Program casebook and field programs | <5 sessions | 42 (65.6) | - | |

| 5–10 sessions | 16 (25.0) | |||

| 11–20 sessions | 4 (6.3) | |||

| 21–30 sessions | - | |||

| ≥31 sessions | - | |||

| Not presented | 2 (3.1) | |||

| Duration (minutes) | Research literature | <30 | 5 (1.3) | 2 (10.0) |

| 30–59 | 107 (27.9) | 4 (20.0) | ||

| 60–89 | 127 (33.2) | 4 (20.0) | ||

| 90–119 | 96 (25.1) | 1 (5.0) | ||

| 120–179 | 28 (7.3) | 3 (15.0) | ||

| ≥180 | 6 (1.6) | 1 (5.0) | ||

| Not presented | 14 (3.6) | 5 (25.0) | ||

| Program casebook and field programs | <30 | 1 (1.6) | - | |

| 30–59 | 5 (7.8) | |||

| 60–89 | 3 (4.7) | |||

| 90–119 | 3 (4.7) | |||

| 120–179 | 17 (26.6) | |||

| ≥180 | 25 (39.1) | |||

| Not presented | 10 (15.6) | |||

| No. | Program Areas | Research Literature | Casebooks and Field Programs | Total | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name of Activity | Psychology | Healthcare and Nursing | Exercise and Rehabilitation | Social Welfare | Horticulture Therapeutic Farming | Forestry | Healthcare and Nursing | Therapeutic Farming | Forestry | |||

| 1 | Recognize value | 13 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 13 | |

| 2 | Recognizing senses | 11 | 1 | 8 | 6 | 1 | 21 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 58 | |

| 3 | Recognizing emotions | 66 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 94 | |

| 4 | Expressing emotions | 16 | 2 | 2 | 24 | 3 | 4 | 1 | - | 3 | 55 | |

| 5 | Recalling the past | 29 | 8 | 1 | 15 | 6 | - | 3 | - | 5 | 67 | |

| 6 | Finding your dream | 34 | 6 | - | 11 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 61 | |

| 7 | Recognizing myself | 97 | 5 | 8 | 20 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 147 | |

| 8 | Analyzing the problem | 19 | 5 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 24 | |

| 9 | Identifying and planning solutions | 16 | 2 | 1 | 2 | - | - | - | - | 1 | 22 | |

| 10 | Implementing and evaluating solutions | 110 | 9 | 8 | 9 | 2 | 3 | 8 | - | 2 | 151 | |

| 11 | Enhancing social skills | 65 | 10 | 9 | 23 | 1 | 15 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 130 | |

| 12 | Recognizing thoughts | 13 | 3 | 2 | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | - | - | 21 | |

| 13 | Finding ways to cope and manage stress | 5 | 3 | - | 2 | - | - | 8 | - | - | 18 | |

| 14 | Recognizing stress | 12 | 1 | 1 | 3 | - | 3 | - | 2 | 1 | 23 | |

| 15 | Expressing stress | 9 | - | 6 | 9 | - | 7 | - | - | 5 | 36 | |

| 16 | Cognitive restructuring and awareness | 9 | 1 | - | 3 | - | - | - | - | - | 13 | |

| 17 | Identifying strengths and weaknesses | 39 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | 2 | 52 | |

| 18 | Becoming aware of the present | 9 | 1 | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | 12 | |

| 19 | Finding happiness | 17 | 6 | - | 4 | - | - | 1 | - | - | 28 | |

| Total | 589 | 68 | 56 | 143 | 22 | 64 | 39 | 11 | 33 | 1025 | ||

| Rank | Research Literature | Casebooks and Field Programs | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychology | Healthcare and Nursing | Exercise and Rehabilitation | Social Welfare | Horticulture Therapeutic Farming | Forestry | Healthcare and Nursing | Therapeutic Farming | Forestry | |

| 1 | Implementing and evaluating solutions | Enhancing social skills | Enhancing social skills | Expressing emotion | Recalling the past | Recognizing senses | Implementing and evaluating solutions and finding ways to cope with and manage stress | Enhancing social skills | Recalling the past, recognizing myself, expressing stress |

| 2 | Recognizing myself | Implementing and evaluating solutions | Recognizing senses, Recognizing myself, finding your dream | Enhancing social skills | Finding your dream | Enhancing social skills | Recognizing senses, Recognizing myself, recognizing stress | ||

| 3 | Recognize emotions | Recalling the past | Recognizing myself | Expressing emotions | Expressing stress | Recognizing senses, recognizing myself | |||

| 4 | Enhancing social skills | Find your dream, Finding happiness | Recalling the past | Recognizing senses, recognizing myself, implementing and evaluating solutions | Expressing emotions, recognizing myself | Recognizing senses | |||

| 5 | Strengths and weaknesses Identifying strengths and weaknesses | Recognizing emotions, expressing stress | Finding your dream | Recognizing emotions, recalling the past, enhancing social skills | Recognizing emotions, finding your dream | Expressing emotions, finding your dream | |||

| No. | Program Areas | Research Literature | Casebooks and Field Programs | Total | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name of Activity | Psychology | Healthcare and Nursing | Exercise and Rehabilitation | Social Welfare | Horticulture Therapeutic Farming | Forestry | Healthcare and Nursing | Therapeutic Farming | Forestry | |||

| 1 | Assigning tasks | 9 | - | 4 | - | 2 | - | - | - | - | 15 | |

| 2 | Setting rules | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | - | - | - | - | 10 | |

| 3 | Playing | 52 | 19 | 9 | 40 | - | - | 2 | - | - | 122 | |

| 4 | Tea ceremony | 15 | - | - | 8 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 34 | |

| 5 | Behavior Expressions | 9 | - | - | 5 | - | 4 | - | - | - | 18 | |

| 6 | Massage | 2 | 5 | - | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 21 | |

| 7 | Crafts | 14 | 3 | - | 14 | 29 | 10 | 7 | 10 | 3 | 90 | |

| 8 | Meditation | 53 | 34 | 13 | 6 | - | 7 | 1 | 2 | 22 | 138 | |

| 9 | Literary activities | 17 | - | - | 7 | - | - | - | 2 | 2 | 28 | |

| 10 | Art activities | 63 | 21 | 5 | 20 | 3 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 132 | |

| 11 | Creating nicknames | 9 | 1 | - | 3 | 2 | 1 | - | 1 | - | 17 | |

| 12 | Stretching | 5 | 1 | 3 | 1 | - | 1 | - | 2 | 8 | 21 | |

| 13 | Body relaxation | 7 | 8 | 5 | 2 | - | - | 7 | 1 | 1 | 31 | |

| 14 | Mind-body workouts | 3 | 6 | 9 | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | 19 | |

| 15 | Ice-breaker | 34 | 3 | 6 | 4 | - | - | 1 | - | 2 | 50 | |

| 16 | Role play | 4 | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | - | 6 | |

| 17 | Yoga | 10 | 7 | 8 | 3 | - | 1 | - | - | 2 | 31 | |

| 18 | Cooking | 7 | 1 | - | 2 | 11 | 2 | 3 | 11 | 1 | 38 | |

| 19 | Laughter activities | 22 | 34 | - | 11 | - | - | - | - | 2 | 69 | |

| 20 | Music activities | 42 | 19 | 7 | 9 | - | - | - | - | 1 | 78 | |

| 21 | Self-introduction | 18 | 5 | 3 | 9 | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | 37 | |

| 22 | Playing with nature | 2 | - | - | - | - | 19 | - | - | 4 | 25 | |

| 23 | Dancing | 9 | 1 | 39 | 5 | - | - | - | - | - | 54 | |

| 24 | Breathing Techniques | 2 | 2 | 4 | 6 | - | 3 | 3 | - | 7 | 27 | |

| 25 | Wrapping up an activity | 24 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | 39 | |

| 26 | Indoor Gardening | 8 | 5 | - | 8 | 30 | - | 2 | 11 | - | 64 | |

| 27 | Outdoor garden | 12 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 10 | - | 22 | |

| 28 | Brain Stimulation exercise | 1 | 3 | 9 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 13 | |

| 29 | Forest Experiences | 4 | 1 | - | - | 3 | 35 | - | 2 | 11 | 56 | |

| 30 | Insect-mediated activities | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | 6 | - | 7 | |

| 31 | Animal-mediated activities | - | - | - | - | - | 2 | - | 3 | - | 5 | |

| 32 | Creative activities | 11 | 1 | 2 | 9 | - | 5 | 1 | - | - | 29 | |

| 33 | Hydrotherapy | - | - | - | - | 2 | 2 | - | 1 | 5 | 10 | |

| 34 | Forest Walking | - | - | - | - | 1 | 8 | - | 2 | 14 | 25 | |

| 35 | Forest writing | - | - | - | - | - | 3 | - | - | 8 | 11 | |

| 36 | Forest Workout | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 16 | 16 | |

| 37 | Storytelling | - | - | - | - | - | 6 | 1 | - | 2 | 9 | |

| 38 | Video Media Activity | - | 5 | - | - | 1 | - | 2 | - | 1 | 9 | |

| 39 | Exercise | - | 10 | 24 | - | - | 1 | - | - | 4 | 39 | |

| 40 | Healing Equipment Experience | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 3 | 3 | |

| Total | 472 | 199 | 156 | 182 | 92 | 124 | 37 | 72 | 134 | 1468 | ||

| Rank | Research Literature | Casebooks and Field Programs | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychology | Healthcare and Nursing | Exercise and Rehabilitation | Social Welfare | Horticulture Therapeutic Farming | Forestry | Healthcare and Nursing | Therapeutic Farming | Forestry | |

| 1 | Art activities | Meditation, laughter activities | Dancing | Playing | Indoor Gardening | Forest Experiences | Crafts, physical relaxation | Cooking Activities, Indoor Gardens | Meditation |

| 2 | Meditation | Exercise | Art activities | Crafts | Playing with nature | Forest Workout | |||

| 3 | Playing | Art activities | Meditation | Crafts | Cooking activities | Crafts | Art activities | Crafts, outdoor gardening | Forest Walking |

| 4 | Music activities | Play, music, and activities | Play, mind-body workout, brain-activating exercise | Laughter activities | Tea ceremonies, art activities, and forest experiences | Art activities, forest walks | Cooking Activities, Breathing Techniques | Forest Experiences | |

| 5 | Icebreaking | Music, Introduce Yourself, Create | Insect-borne activity | Stretching, Forest writing | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, G.; Kang, S.; Paek, K.; Lee, N.; Min, G.; Seo, Y.; Park, S.; Park, S.; Choi, H.; Choi, S.; et al. Analysis of Program Activities to Develop Forest Therapy Programs for Improving Mental Health: Focusing on Cases in Republic of Korea. Healthcare 2025, 13, 760. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070760

Kim G, Kang S, Paek K, Lee N, Min G, Seo Y, Park S, Park S, Choi H, Choi S, et al. Analysis of Program Activities to Develop Forest Therapy Programs for Improving Mental Health: Focusing on Cases in Republic of Korea. Healthcare. 2025; 13(7):760. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070760

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Gayeon, Sinae Kang, Kyungsook Paek, Neeeun Lee, Gyeongmin Min, Youngeun Seo, Sooil Park, Seyeon Park, Hyoju Choi, Saeyeon Choi, and et al. 2025. "Analysis of Program Activities to Develop Forest Therapy Programs for Improving Mental Health: Focusing on Cases in Republic of Korea" Healthcare 13, no. 7: 760. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070760

APA StyleKim, G., Kang, S., Paek, K., Lee, N., Min, G., Seo, Y., Park, S., Park, S., Choi, H., Choi, S., & Yeon, P. (2025). Analysis of Program Activities to Develop Forest Therapy Programs for Improving Mental Health: Focusing on Cases in Republic of Korea. Healthcare, 13(7), 760. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070760