Post-COVID-19 Syndrome as Described by Patients: A Qualitative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

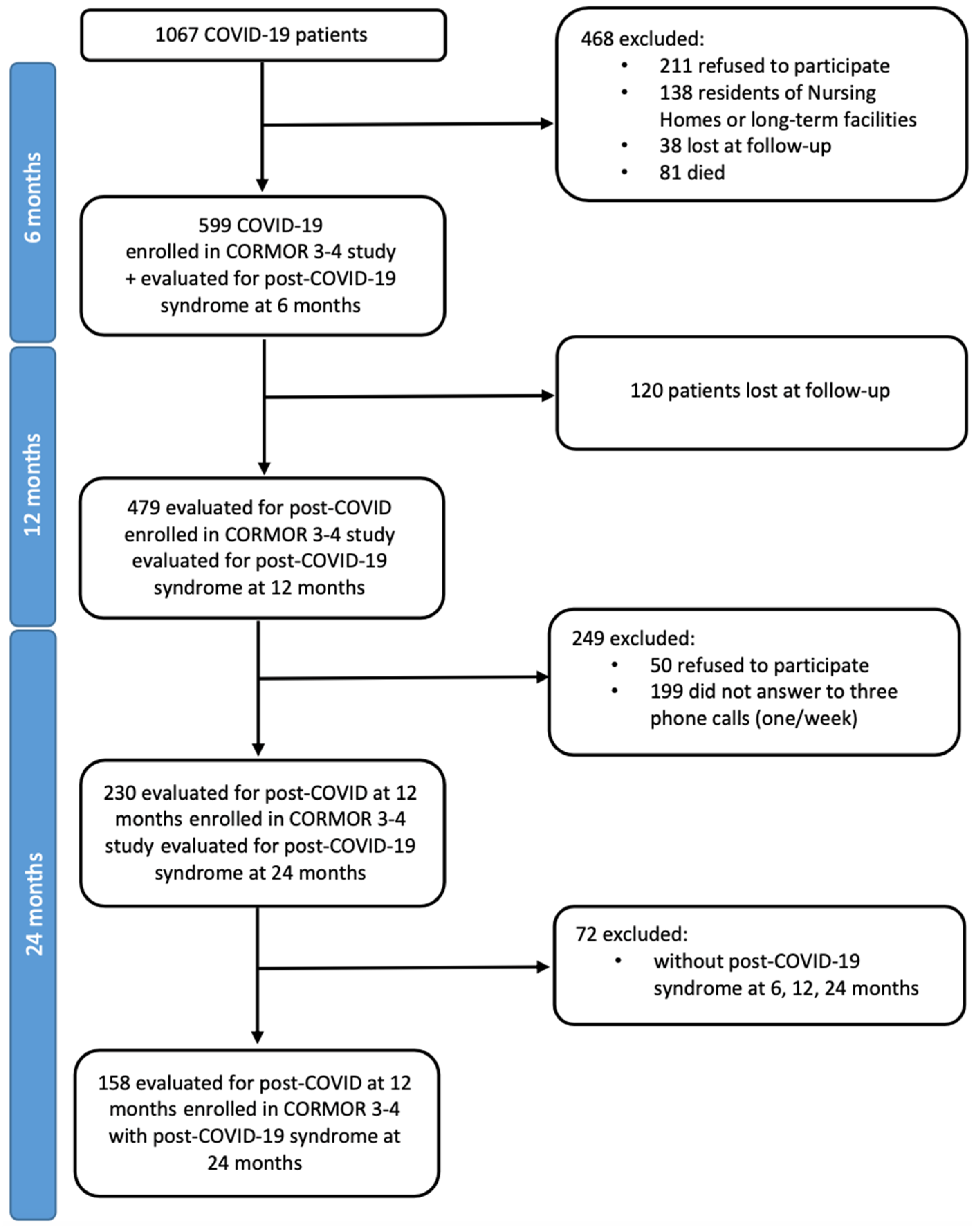

2.2. Setting and Participants

2.3. Data Collection Methods and Instruments

2.4. Data Collection Process and Rigor

2.5. Data Analysis

2.6. Ethical Issues

3. Results

3.1. Patients’ Characteristics

3.2. Post-COVID-19 Syndrome According to Patients’ Knowledge and Perception

3.3. Post-COVID-19 Syndrome as Described by Patients

3.3.1. Experiencing Interrelated Physical and Psychological Symptoms

3.3.2. Fighting like Warriors for a Long Time

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ARDS | Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| CORMOR | CORonavirus MOnitoRing |

| HCW | Healthcare Worker |

| PHEIC | Public Health Emergency of International Concern |

| P | Patient’s anonymous identifier number |

| PhD | Doctor of Philosophy |

| RN | Registered Nurse |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Severe Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 |

| SRQR | Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- World Health Organization. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pandemic. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/emergencies/situations/covid-19 (accessed on 3 January 2025).

- Harris, E. WHO Declares End of COVID-19 Global Health Emergency. JAMA 2023, 329, 1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maqbool, A.; Khan, N.Z. Analyzing barriers for implementation of public health and social measures to prevent the transmission of COVID-19 disease using DEMATEL method. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2020, 14, 887–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. COVID-19 Vaccines; World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/covid-19-vaccines (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Funada, S.; Yoshioka, T.; Luo, Y.; Iwama, T.; Mori, C.; Yamada, N.; Yoshida, H.; Katanoda, K.; Furukawa, T.A. Global Trends in Highly Cited Studies in COVID-19 Research. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2332802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivan, M.; Ormerod, M.; Maini, R. Does timely vaccination help prevent post-viral conditions? BMJ 2023, 383, p2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, J.D.; Shen, Q.; Cintron, S.A.; Hiebert, J.B. Post-COVID-19 Syndrome. Nurs. Res. 2022, 71, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Knight, M.; A’Court, C.; Buxton, M.; Husain, L. Management of post-acute COVID-19 in primary care. BMJ 2020, 370, m3026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menges, D.; Ballouz, T.; Anagnostopoulos, A.; Aschmann, H.E.; Domenghino, A.; Fehr, J.S.; Puhan, M.A. Burden of post-COVID-19 syndrome and implications for healthcare service planning: A population-based cohort study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0254523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peghin, M.; De Martino, M.; Palese, A.; Chiappinotto, S.; Fonda, F.; Gerussi, V.; Sartor, A.; Curcio, F.; Grossi, P.A.; Isola, M.; et al. Post-COVID-19 Syndrome 2 Years After the First Wave: The Role of Humoral Response, Vaccination and Reinfection. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2023, 10, ofad364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palese, A.; Visintini, E.; Bressan, V.; Fonda, F.; Chiappinotto, S.; Grassetti, L.; Peghin, M.; Tascini, C.; Balestrieri, M.; Colizzi, M. Using Metaphors to Understand Suffering in COVID-19 Survivors: A Two Time-Point Observational Follow-Up Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostowlansky, T.; Rota, A. Emic and etic. In The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Anthropology; Stein, F., Lazar, S., Candea, M., Diemberger, H., Robbins, J., Sanchez, A., Stasch, R., Eds.; University of Cambridge: Cambridge, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Berner-Rodoreda, A.; Baum, N.; Wachinger, J.; Zangerl, K.; Hoegl, H.; Bärnighausen, T. Taking emic and etic to the family level: Interlinking parents’ and children’s COVID-19 views and experiences in Germany. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caimmi, P.P.; Capponi, A.; Leigheb, F.; Occo, F.D.; Sacco, R.; Minola, M.; Kapetanakis, E.I. The Hard Lessons Learned by the COVID-19 Epidemic in Italy: Rethinking the Role of the National Health Care Service? J. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2021, 11, 266–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charalampous, P.; GBD 2021 Demographics Collaborators. Global age-sex-specific mortality, life expectancy, and population estimates in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1950–2021, and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic: A comprehensive demographic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2024, 403, 1989–2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigorè, M.; Steccanella, A.; Maffoni, M.; Torlaschi, V.; Gorini, A.; La Rovere, M.T.; Maestri, R.; Bussotti, M.; Masnaghetti, S.; Fanfulla, F.; et al. Patients’ Clinical and Psychological Status in Different COVID-19 Waves in Italy: A Quanti-Qualitative Study. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretti, C.; Collaro, C.; Terzoni, C.; Colucci, G.; Copelli, M.; Sarli, L.; Artioli, G. Dealing with uncertainty. A qualitative study on the illness’ experience in patients with Long-COVID in Italy. Acta Biomed. 2022, 93, e2022349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandelowski, M. What’s in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Res. Nurs. Health 2010, 33, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villamin, P.; Lopez, V.; Thapa, D.K.; Cleary, M. A Worked Example of Qualitative Descriptive Design: A Step-by-Step Guide for Novice and Early Career Researchers. J. Adv. Nurs. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graneheim, U.H.; Lundman, B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ. Today 2004, 24, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vears, D.F.; Gillam, L. Inductive content analysis: A guide for beginning qualitative researchers. Focus Health Prof. Educ. Multi-Prof. J. 2022, 23, 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingsley, C.; Patel, S. Patient-reported outcome measures and patient-reported experience measures. BJA Educ. 2017, 17, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubrium, A.; Gubrium, E. Narrative complexity in the time of COVID-19. Lancet 2021, 397, 2244–2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, B.C.; Harris, I.B.; Beckman, T.J.; Reed, D.A.; Cook, D.A. Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Acad. Med. 2014, 89, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Living Guidance for Clinical Management of COVID-19: Living Guidance; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. EUSurvey v. 1.5.2.9. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eusurvey/home/welcome (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Hannah, D.R.; Lautsch, B.A. Counting in Qualitative Research: Why to Conduct it, When to Avoid it, and When to Closet it. J. Manag. Inq. 2011, 20, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahry, N.R.; Ling, J.; Robbins, L.B. Mental health and lifestyle behavior changes during COVID-19 among families living in poverty: A descriptive phenomenological study. J. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2024, 37, e12447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, N.; Bryant-Lukosius, D.; DiCenso, A.; Blythe, J.; Neville, A.J. The use of triangulation in qualitative research. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2014, 41, 545–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flick, U. (Ed.) Revitalising Triangulation for Designing Multi-Perspective Qualitative Research. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research Design; SAGE: London, UK, 2022; Chapter 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Haupert, S.R.; Zimmermann, L.; Shi, X.; Fritsche, L.G.; Mukherjee, B. Global Prevalence of Post-Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Condition or Long COVID: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 226, 1593–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayoubkhani, D.; Munro, M. Prevalence of Ongoing Symptoms Following Coronavirus (COVID-19) Infection in the UK: 6 May 2022; Office for National Statistics: London, UK, 2022; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, E.; Poole, R. Living with COVID-19 Second Review: A Dynamic Review of the Evidence Around Ongoing COVID-19 (Often Called Long Covid). NIHR Evidence Collection. 2021. Available online: https://evidence.nihr.ac.uk/collection/living-with-covid19-second-review/ (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Bai, F.; Tomasoni, D.; Falcinella, C.; Barbanotti, D.; Castoldi, R.; Mulè, G.; Augello, M.; Mondatore, D.; Allegrini, M.; Cona, A.; et al. Female gender is associated with long COVID syndrome: A prospective cohort study. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2022, 28, 611.e9–611.e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, F.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, X.; Cen, Y.; Wang, B.; Zhao, S.; Zhou, Y.; Hu, B.; Wang, M.; et al. Symptoms and Health Outcomes Among Survivors of COVID-19 Infection 1 Year After Discharge From Hospitals in Wuhan, China. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2127403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perlis, R.H.; Green, J.; Santillana, M.; Lazer, D.; Ognyanova, K.; Simonson, M.; Baum, M.A.; Quintana, A.; Chwe, H.; Druckman, J.; et al. Persistence of symptoms up to 10 months following acute COVID-19 illness. medRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desgranges, F.; Tadini, E.; Munting, A.; Regina, J.; Filippidis, P.; Viala, B.; Karachalias, E.; Suttels, V.; Haefliger, D.; Kampouri, E.; et al. Post-COVID-19 Syndrome in Outpatients: A Cohort Study. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2022, 37, 1943–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, S.; Haldar, S.N.; Soneja, M.; Mundadan, N.G.; Garg, P.; Mittal, A.; Desai, D.; Trilangi, P.K.; Chakraborty, S.; Begam, N.N.; et al. Post COVID-19 sequelae: A prospective observational study from Northern India. Drug Discov. Ther. 2021, 15, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalbandian, A.; Sehgal, K.; Gupta, A.; Madhavan, M.V.; McGroder, C.; Stevens, J.S.; Cook, J.R.; Nordvig, A.S.; Shalev, D.; Sehrawat, T.S.; et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 601–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, Q.; Xu, M.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xu, Y.; Dong, W. Clinical sequelae of COVID-19 survivors in Wuhan, China: A single-centre longitudinal study. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2021, 27, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halpin, S.J.; McIvor, C.; Whyatt, G.; Adams, A.; Harvey, O.; McLean, L.; Walshaw, C.; Kemp, S.; Corrado, J.; Singh, R.; et al. Postdischarge symptoms and rehabilitation needs in survivors of COVID-19 infection: A cross-sectional evaluation. J. Med. Virol. 2021, 93, 1013–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudre, C.H.; Murray, B.; Varsavsky, T.; Graham, M.S.; Penfold, R.S.; Bowyer, R.C.; Pujol, J.C.; Klaser, K.; Antonelli, M.; Canas, L.S.; et al. Attributes and predictors of long COVID. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 626–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, H.E.; Assaf, G.S.; McCorkell, L.; Wei, H.; Low, R.J.; Re’em, Y.; Redfield, S.; Austin, J.P.; Akrami, A. Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact. EClinicalMedicine 2021, 38, 101019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Leon, S.; Wegman-Ostrosky, T.; Perelman, C.; Sepulveda, R.; Rebolledo, P.A.; Cuapio, A.; Villapol, S. More than 50 long-term effects of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 16144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaf, G.; Davis, H.; McCorkell, L.; Wei, H.; O’Neil, B.; Akrami, A.; Low, R.; Mercier, J.; Adetutu, A. COVID-19 Prolonged Symptoms Survey—Analysis Report. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Long, C.P. About Long COVID Physio. Available online: https://longcovid.physio/about (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- World Physiotherapy. World Physiotherapy Response to COVID-19 Briefing Paper 9. Safe Rehabilitation Approaches for People Living with Long COVID: Physical Activity and Exercise; World Physiotherapy: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Palese, A.; Peghin, M.; Bressan, V.; Venturini, M.; Gerussi, V.; Bontempo, G.; Graziano, E.; Visintini, E.; Tascini, C. One Word to Describe My Experience as a COVID-19 Survivor Six Months after Its Onset: Findings of a Qualitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COVID-19 Open Access, P. Living Evidence on COVID-19. Available online: https://ispmbern.github.io/covid-19/living-review/ (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Aiyegbusi, O.L.; Hughes, S.E.; Turner, G.; Rivera, S.C.; McMullan, C.; Chandan, J.S.; Haroon, S.; Price, G.; Davies, E.H.; Nirantharakumar, K.; et al. Symptoms, complications and management of long COVID: A review. J. R. Soc. Med. 2021, 114, 428–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brehon, K.; Miciak, M.; Hung, P.; Chen, S.P.; Perreault, K.; Hudon, A.; Wieler, M.; Hunter, S.; Hoddinott, L.; Hall, M.; et al. “None of us are lying”: An interpretive description of the search for legitimacy and the journey to access quality health services by individuals living with Long COVID. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasselin, J.; Lekander, M.; Benson, S.; Schedlowski, M.; Engler, H. Sick for science: Experimental endotoxemia as a translational tool to develop and test new therapies for inflammation-associated depression. Mol. Psychiatry 2021, 26, 3672–3683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennessy, M.B.; Deak, T.; Schiml, P.A. Sociality and sickness: Have cytokines evolved to serve social functions beyond times of pathogen exposure? Brain Behav. Immun. 2014, 37, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceban, F.; Ling, S.; Lui, L.M.W.; Lee, Y.; Gill, H.; Teopiz, K.M.; Rodrigues, N.B.; Subramaniapillai, M.; Di Vincenzo, J.D.; Cao, B.; et al. Fatigue and cognitive impairment in Post-COVID-19 Syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav. Immun. 2022, 101, 93–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton, C.W.; Downs, C.A.; Hughes, T.; Lambert, N.; Abrahim, H.L.; Herrera, M.G.; Huang, Y.; Rahmani, A.; Lee, J.A.; Chakraborty, R.; et al. A novel conceptual model of trauma-informed care for patients with post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 illness (PASC). J. Adv. Nurs. 2022, 78, 3618–3628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macpherson, K.; Cooper, K.; Harbour, J.; Mahal, D.; Miller, C.; Nairn, M. Experiences of living with long COVID and of accessing healthcare services: A qualitative systematic review. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e050979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Sivan, M.; Perlowski, A.; Nikolich, J. Long COVID: A clinical update. Lancet 2024, 404, 707–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCorkell, L.; Peluso, M.J. Long COVID research risks losing momentum—We need a moonshot. Nature 2023, 622, 457–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pigaiani, Y.; Zoccante, L.; Zocca, A.; Arzenton, A.; Menegolli, M.; Fadel, S.; Ruggeri, M.; Colizzi, M. Adolescent Lifestyle Behaviors, Coping Strategies and Subjective Wellbeing during the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Online Student Survey. Healthcare 2020, 8, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortoletto, R.; Di Gennaro, G.; Antolini, G.; Mondini, F.; Passarella, L.; Rizzo, V.; Silvestri, M.; Darra, F.; Zoccante, L.; Colizzi, M. Sociodemographic and clinical changes in pediatric in-patient admissions for mental health emergencies during the COVID-19 pandemic: March 2020 to June 2021. Psychiatry Res. Commun. 2022, 2, 100023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nersesjan, V.; Christensen, R.H.B.; Kondziella, D.; Benros, M.E. COVID-19 and Risk for Mental Disorders Among Adults in Denmark. JAMA Psychiatry 2023, 80, 778–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpert, O.; Begun, L.; Garren, P.; Solhkhah, R. Cytokine storm induced new onset depression in patients with COVID-19. A new look into the association between depression and cytokines-two case reports. Brain Behav. Immun. Health 2020, 9, 100173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, R.C.; Sharma, V.K.; Tan, B.Y.Q.; Ng, A.Y.Y.; Lui, Y.S.; Husain, S.F.; Ho, C.S.; Tran, B.X.; Pham, Q.H.; McIntyre, R.S.; et al. Comparison of Brain Activation Patterns during Olfactory Stimuli between Recovered COVID-19 Patients and Healthy Controls: A Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS) Study. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. A Clinical Case Definition of Post COVID-19 Condition by a Delphi Consensus. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Post_COVID-19_condition-Clinical_case_definition-2021.1 (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- World Health Organization. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19): Post COVID-19 Condition. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/coronavirus-disease-(covid-19)-post-covid-19-condition (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- World Health Organization Europe. Post COVID-19 Condition (Long COVID). Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/news-room/fact-sheets/item/post-covid-19-condition (accessed on 14 January 2025).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Research Action Plan on Long COVID. Available online: https://www.covid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/National-Research-Action-Plan-on-Long-COVID-08012022.pdf (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- National Health Service. Long-term Effects of COVID-19 (Long COVID). Available online: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/covid-19/long-term-effects-of-covid-19-long-covid/ (accessed on 14 January 2025).

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. COVID-19 Rapid Guideline: Managing the Long-Term Effects of COVID-19. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng188/chapter/1-Identification (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- Onder, G.; Floridia, M.; Giuliano, M.; Lo Noce, C.; Tiple, D.; Bertinato, L.; Mariniello, R.; Laganà, M.G.; Della Vecchia, A.; Gianferro, R.; et al. Indicazioni ad Interim sui Principi di Gestione del Long-COVID; Istituto Superiore di Sanità: Roma, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

| Patients’ Characteristics | Responded to Follow-Up at 24 Months N = 230 | Patients Who Experienced Post-COVID-19 Syndrome N = 158 |

|---|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) | ||

| Female | 123 (53.5) | 94 (59.5) |

| Male | 107 (46.5) | 64 (40.5) |

| Age group, n (%) | ||

| 18–40 | 44 (19.1) | 22 (13.9) |

| 41–60 | 99 (43.0) | 76 (48.1) |

| >60 | 87 (37.8) | 60 (38.0) |

| Ethnicity, n/N (%) | ||

| Native Italian | 206/217 (94.9) | 145/152 (95.4) |

| European | 11/217 (5.1) | 7/152 (4.6) |

| Smoking habit, n/N (%) | ||

| Non-smoker | 144/228 (63.2) | 102/157 (65.0) |

| Smoker | 28/268 (12.3) | 17/157 (10.8) |

| Ex-smoker | 56/268 (24.6) | 38/157 (24.2) |

| Alcohol habit, n/N (%) | ||

| Non-drinker | 109/227 (48.0) | 81/156 (51.9) |

| Drinker | 116/227 (51.1) | 74/156 (47.4) |

| Alcohol use disorder | 2/227 (0.9) | 1/156 (0.6) |

| Work, n/N (%) | ||

| HCWs | 47 (22.5) | 29/146 (19.9) |

| Work in contact with public | 37 (17.7) | 26/146 (17.8) |

| Work not in contact with the public | 65 (31.1) | 43/146 (29.5) |

| Retired | 35 (16.8) | 24/146 (16.4) |

| Other | 23 (12.0) | 24/146 (16.4) |

| Co-morbidities, number, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 107 (46.5) | 64 (40.5) |

| 1 | 66 (28.7) | 49 (31.0) |

| 2 | 32 (13.9) | 25 (15.8) |

| 3 | 16 (7.0) | 12 (7.6) |

| ≥4 | 9 (3.9) | 8 (5.1) |

| Co-morbidities, n/N (%) | ||

| Hypertension | 47/226 (20.8) | 35/156 (22.4) |

| Obesity | 29 (12.6) | 20 (12.7) |

| Diabetes | 15/229 (6.6) | 9 (5.7) |

| Chronic respiratory disease | 8/229 (3.5) | 8 (5.1) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 4/225 (1.8) | 2 (1.3) |

| Liver disease | 7/229 (3.1) | 7 (4.4) |

| Psychiatric disorders | 3 (1.3) | 2 (1.3) |

| Renal impairment | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Under chronic medication, n/N (%) | ||

| Yes | 105/227 (46.3) | 78/157 (49.7) |

| No | 122/227 (53.7) | 79/157 (50.3) |

| Acute COVID-19 severity, n/N (%) | ||

| Asymptomatic | 17/229 (7.4) | 5 (3.2) |

| Mild | 155/229 (67.7) | 110 (69.6) |

| Moderate, Severe and critical | 57/229 (24.9) | 43 (27.2) |

| Symptoms at onset, number, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 27 (11.7) | 9 (5.7) |

| 1 | 35 (15.2) | 17 (10.8) |

| 2 | 49 (21.3) | 29 (18.3) |

| 3 | 31 (13.5) | 24 (15.2) |

| 4 | 43 (18.7) | 36 (22.8) |

| ≥5 | 43 (19.6) | 43 (27.2) |

| Management at the onset, n (%) | ||

| Outpatients | 164 (71.3) | 106 (67.1) |

| Inpatients | ||

| Ward | 54 (23.5) | 44 (27.8) |

| ICU | 12 (5.2) | 8 (5.1) |

| Length of in-hospital stay, days, median (IQR) | 7 (4–10) | 7 (4–9) |

| Post-COVID-19 syndrome 6 months, n (%) | 104 (45.2) | 104 (65.8) |

| Post-COVID-19 syndrome 12 months, n (%) | 114 (49.6) | 114 (72.2) |

| At least one post-COVID-19 symptom at 24 months, n (%) | 83 (36.1) | 83 (52.5) |

| Number of post-COVID-19 symptoms at 24 months, median (IQR) | 3 (2–4) | 3 (2–4) |

| Patients without post-COVID-19 syndrome at 6, 12, 24 months, n/N (%) | 72/230 (31.3) |

| At 24 Months After the COVID-19 Onset | N = 158 |

|---|---|

| Do you know what is the post-COVID-19 syndrome?, n (%) | |

| Yes | 75 (47.5) |

| No | 46 (29.1) |

| Maybe/uncertain | 37 (23.4) |

| What is the source of your knowledge regarding the syndrome?, n/N (%) | |

| General Practitioner | 30/156 (19.2) |

| Specialized Physician | 12/156 (7.7) |

| Internet | 44/156 (28.2) |

| Media (television, newspapers) | 45/156 (28.9) |

| Other | 25/156 (16.0) |

| Do you think you suffer from this syndrome at 24 months?, n (%) | |

| Yes | 46 (29.1) |

| No | 69 (43.7) |

| Maybe/uncertain | 43 (27.2) |

| Theme | Category | N = 136 (100%) |

|---|---|---|

| Codes | ||

| Experiencing interrelated physical and psychological symptoms | Physical manifestations: struggling between pain and fatigue | 77 (56.6) |

| Fatigue | 41 (53.2) | |

| Pain | 11 (14.3) | |

| Dyspnea | 9 (11.7) | |

| Alteration of the senses | 4 (5.2) | |

| Faintness | 2 (2.6) | |

| Heart disease | 2 (2.6) | |

| Intestinal disorder | 1 (1.3) | |

| Flu | 1 (1.3) | |

| Weakness | 1 (1.3) | |

| Lack of appetite | 1 (1.3) | |

| Hypoesthesia | 1 (1.3) | |

| Sore throat | 1 (1.3) | |

| Cough | 1 (1.3) | |

| Weight loss | 1 (1.3) | |

| Emotional storm | 30 (22.1) | |

| Fear | 5 (16.7) | |

| Anxiety | 4 (13.3) | |

| Depression | 4 (13.3) | |

| Stress | 3 (10.0) | |

| Nuisance | 2 (6.7) | |

| Insomnia | 2 (6.7) | |

| Burden | 2 (6.7) | |

| Trauma | 1 (3.3) | |

| Sadness | 1 (3.3) | |

| Melancholy | 1 (3.3) | |

| Lack of desire | 1 (3.3) | |

| Exhaustion | 1 (3.3) | |

| Concerns | 1 (3.3) | |

| Irritability | 1 (3.3) | |

| Being apathy | 1 (3.3) | |

| Like a fog in my brain | 10 (7.4) | |

| Memory loss | 5 (50.0) | |

| Feeling mental fatigue | 2 (20.0) | |

| Being in a mental fog | 2 (20.0) | |

| Losing concentration | 1 (10.0) | |

| Fighting like warriors for a long time | It left something in me | 18 (13.2) |

| Long-term consequences | 13 (72.2) | |

| I am not as before | 3 (16.7) | |

| Impact | 2 (11.1) | |

| Experiencing something new | 16 (11.8) | |

| An endless story | 27 (19.9) | |

| Persistent symptoms | 22 (81.5) | |

| Debilitating syndrome | 4 (14.8) | |

| Intermittent symptoms | 1 (3.7) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fonda, F.; Chiappinotto, S.; Visintini, E.; D’Elia, D.; Ngwache, T.; Peghin, M.; Tascini, C.; Balestrieri, M.; Colizzi, M.; Palese, A. Post-COVID-19 Syndrome as Described by Patients: A Qualitative Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 757. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070757

Fonda F, Chiappinotto S, Visintini E, D’Elia D, Ngwache T, Peghin M, Tascini C, Balestrieri M, Colizzi M, Palese A. Post-COVID-19 Syndrome as Described by Patients: A Qualitative Study. Healthcare. 2025; 13(7):757. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070757

Chicago/Turabian StyleFonda, Federico, Stefania Chiappinotto, Erica Visintini, Denise D’Elia, Terence Ngwache, Maddalena Peghin, Carlo Tascini, Matteo Balestrieri, Marco Colizzi, and Alvisa Palese. 2025. "Post-COVID-19 Syndrome as Described by Patients: A Qualitative Study" Healthcare 13, no. 7: 757. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070757

APA StyleFonda, F., Chiappinotto, S., Visintini, E., D’Elia, D., Ngwache, T., Peghin, M., Tascini, C., Balestrieri, M., Colizzi, M., & Palese, A. (2025). Post-COVID-19 Syndrome as Described by Patients: A Qualitative Study. Healthcare, 13(7), 757. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070757