6-Minute Walk Test: Exploring Factors Influencing Perceived Intensity in Older Patients Undergoing Cardiac Rehabilitation—A Qualitative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria of the Patients

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria of the Therapists

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Description of the Study Process

2.5. Coding Process

3. Results

3.1. Results of the Physiotherapists

“But it just doesn’t match what we expect through the test. So, I already find that somebody can recognize that the patient is actually not exerting to a high degree. And often, when I get a three or a four, I think: Yes, you look like that (...). But it doesn’t correspond to what we would like.”(Female, 31 years; 6 years of experience.)

3.2. Results of the Patients

3.3. Results of Open Coding of Both Groups

3.4. Summary of the Conceptual Categories

3.5. Physical Limitations

3.6. Fears

“Well, I wouldn’t have dared to set the tempo in such a way I would have been capable for fear of burning muscles.”(No. 1; 80 years old, male, after bypass operation (BO).)

3.7. Instruction

“You have to get mentally into that scale first.”(No. 2, 66 years old, male, after percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty.)

3.8. Test Conditions

“But I know that the test is not for me, it’s for you or your work and it can be very helpful. Right? But for me personally, it doesn’t matter, does it?”(No. 8.)

“(...) when I do this exercise [the 6-MWT], I know now that I have to make an effort to get there and to get an effect then. But in everyday life, I don’t think so.”(No. 1.)

“Yes, but I don’t really ask myself that. The work, does it bother me now or not. I just have to get it done.”(No. 1.)

3.9. Self-Image at Retirement Age in Coronary Heart Disease

“So, I think what changes the most [with age] is the serenity, just not getting excited so quickly, letting it be what it is. I don’t think it was like that in the younger years, but now it’s serenity, enjoying. Yeah, I think that’s changing—to be satisfied. You’ve had life for the most part; now there’s the beauty to come (...)”(No. 7, 67 years old, male, after BO.)

“So, with Nordic walking, initially I could always keep up with all the participants. And then, lately, I noticed that I was struggling uphill. And then I started to fall behind. Maybe I could have tried harder, but it was also something indeterminate, wasn’t it? And then I didn’t totally push the envelope either, did I?”(No. 1.)

“Normally, the effort should be at most moderately difficult. You should also be able to enjoy it. That’s actually the goal. Good on foot, not too heavy, enjoy and still do something for your health.”(No. 6, 75 years old, male, after BO.)

“So, when I’m really at the limit, then I say six or five, (...) it’s [the] maximum, (...) a limit has been reached, so I really can’t go any further. But (...), that’s not absolute, so in the past, I might have been able to do a lot more and now it’s just within the framework, the limit, right?”(No. 2.)

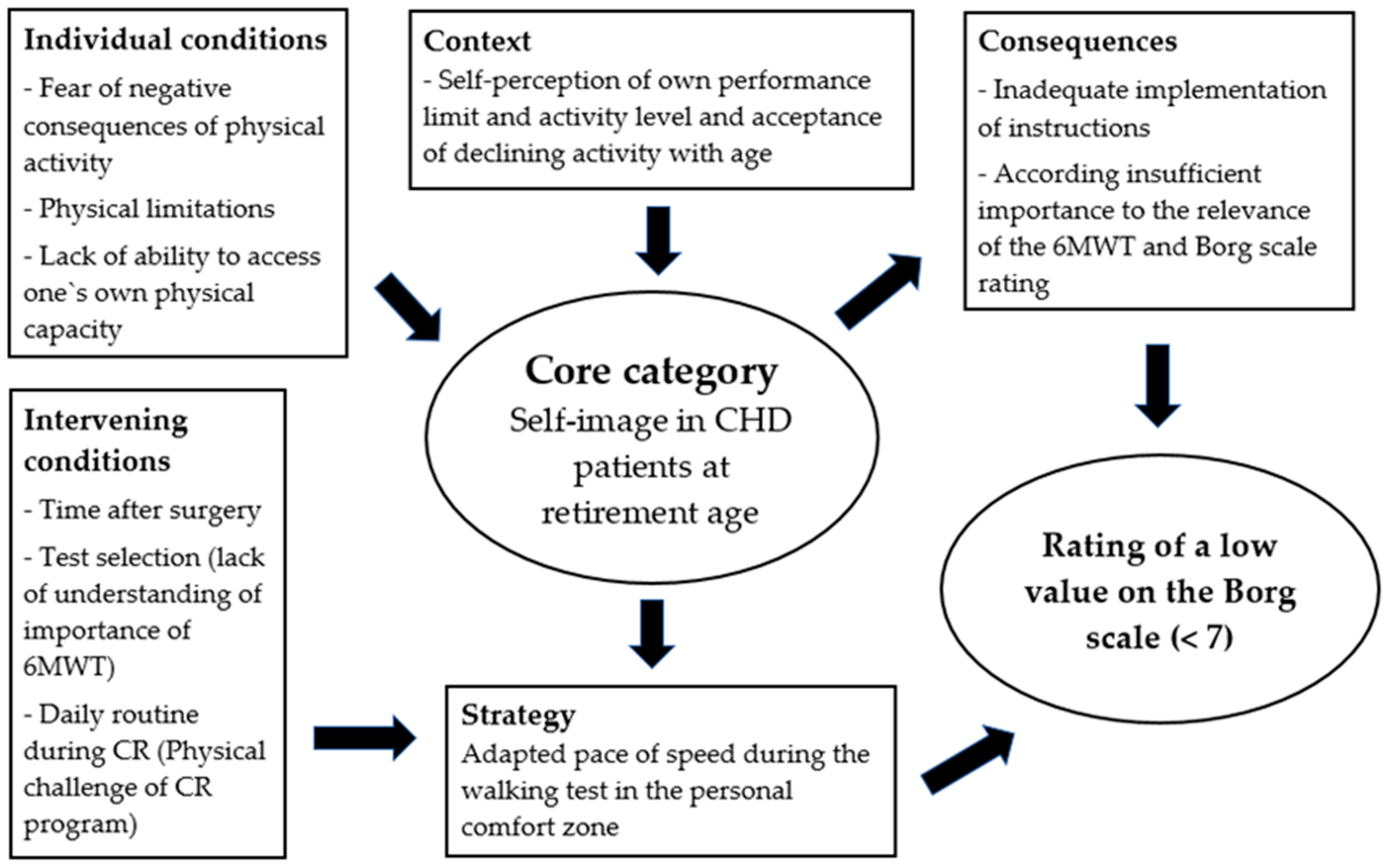

3.10. Axial and Selective Coding

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Results of the Questionnaire of the Patients

- Instruction and Understanding

- Honesty

- Four patients reported that they were unable to reliably assess themselves in terms of indicating exercise intensity, e.g., due to their “heart surgery” and in terms of “relation” (i.e., to their previous activity level; question 4).

- Perception

- One patient stated that effort was difficult to assess after “surgery”. Five patients perceived exertion concerning breathing, three related it to heartbeat, and others associated exertion with activities when “walking” or “riding a seated bicycle”. Another patient perceived fatigue (question 5—free text).

- Self-Assessment of Physical Activity

- When asked whether they had pushed themselves to the limit before the cardiac event, the patients rated themselves on a scale of 0 to 10 with values between 2 and 10 ( = 6.2; 0 = rather no; 10 = rather yes). After the acute event of heart disease, this assessment was significantly lower in five subjects than before the event ( = 5.2; minimum: 0; maximum: 10; question 6).

- Security

- The feeling of being safe during the 6-MWT was reported differently by the patients on a scale of 0 to 10, and the mean value was = 7.5 (minimum: 0; maximum: 10; question 7). In three patients, the value was less than five.

- Physical Performance Limit

- The patients were able to indicate in free text what would generally prevent them from reaching their performance limits. For example, they named physical symptoms, such as “tiredness”, “pain”, “shortness of breath”, “dizziness”, or “the ability to walk”, as well as “their current state of health” (question 8).

- As a restriction to reaching their own performance limit in the current situation, the patients listed, for example, keywords related to “heart rate” as well as “pain”, “operations”, “fear”, “restlessness”, and “an uncertainty due to illness” (question 9).

- Self-Assessment as a Sporty Person

- The answer to the question of to what extent the patients considered themselves to be a person who is active in sports on a scale of 0 to 10 was rated very differently, with a mean value of = 5.0 (minimum: 0; maximum: 8; question 10).

- Maximum Effort and Limits in Physical Activity

- As strong stressors before and after the acute phase of the heart disease, the patients named sports activities such as cycling or running, but also everyday activities such as climbing stairs and walking (question 11; only one respondent’s answer was inconclusive, as she entered a value instead of an activity).

- When asked how long it had been since they had exerted themselves to the maximum during an activity, four subjects stated that it had been longer than a year ago, and three of the patients wrote that it had been several years ago. Three patients answered that it had been a few weeks ago (question 12).

- Patients cited the following as reasons for not being able to continue to exert themselves in the test: “previous traffic accident”, “no need”, physical symptoms, such as “breathing” and “weakness”, but also “insecurity” and “age” (question 13).

Appendix B

| Main Category | Definition | 1. Subcategory | Definition | 2. Subcategory | Definition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-image at retirement age in CHD | The idea that patients with CHD have of themselves is based on self-image, which controls thinking, feeling, and behavior | Self-perception of own performance limit and activity level | Assessment of the current activity level is related to the experience of the previous activity level and performance (current due to illness or months and/or years ago) | In the well-being area | Offers security and feels comfortable, e.g., breaks set by yourself |

| # An acceptance (or lack thereof) of declining activity in old age | The limits of physical activity are (not) accepted | ||||

| Influenced by a lack of ability to assess one’s capacity | The patients express that they have difficulty assessing their capacity | ||||

| Evaluation of self-perception not comprehensible by therapists | Patients give a different assessment of self-perception—different from the assessment of others | ||||

| Indication of a low value on the Borg Scale, below seven | Patients state that they cannot/do not want to burden themselves any further | ||||

| Due to the influence of the outside | Patients are influenced by their social environment or do not like to show up in public when they walk slower or need aid | ||||

| Physical limitations | Physical limitations that the patient perceives | Due to the effects of CHD, including the consequences of surgery | Signs and symptoms of coronary artery disease and/or sequelae of surgery | ||

| Due to an age-related, decreasing fitness level | Reduction of muscle strength, endurance, and balance | ||||

| By secondary diagnoses | Diagnoses other than coronary artery disease that relate to exercise capacity | ||||

| Through the physical sensation of stress | Loads that arise physiologically | ||||

| * Through hygiene regulations | Patients must wear face masks due to COVID-19 regulation | ||||

| Fears | Any possible negative events, dangers, or negative feelings that could result from the test and lead to the patient’s restraint | Insecurity | Patients experience feelings of insecurity because they are not able to adequately process or interpret the current (disease) situation | ||

| Anxiety | Patients perceive stress as threatening | ||||

| Instruction | Give instructions on the walking test and the effort scale | Receptivity | Ability to cognitively absorb information | ||

| Implement instructions | The ability of the patients to implement the instructions adequately | # Influenced by unclear or misunderstood physician guidelines | Load specifications or restrictions are not communicated or included | ||

| Influences the classification of the speed during the walking test | Assumption of how the instruction is translated into a self-selected speed | ||||

| * Interaction: therapist–patient | Statements about the interaction between the therapist and patient during the test | ||||

| Lack of instruction in the test itself | The patient is not sufficiently informed about the test | ||||

| Timing of the instruction for the load intensity | Instruction of the Borg Scale before the test | ||||

| Test conditions | All organizational, content-related, spatial, and personal aspects necessary for the implementation of the 6-MWT and application of the Borg Scale | ||||

| (A) Organizational | Query timing | When is the load intensity inquired? | |||

| Daily schedule | Time of the test and general load during the day | ||||

| * Adherence to the dates | “Slow” and indecisive patients go beyond the scheduled test appointment time | ||||

| Time after surgery | An earlier or later date for scheduling the walking test after surgery | ||||

| (B) Content | * Learning effect | Improvement through repetition | |||

| Test selection | The test is not suitable for the subjects | ||||

| Meaning of the test | The 6-MWT has relevance for patients | ||||

| The low importance of the Borg Scale | Use of the Borg Scale in everyday life is low | ||||

| Influenced by the importance of the load intensity | The patients do not rate the intensity as important for their everyday life | ||||

| (C) Spatial | Surroundings | Interference from facilities or persons presents other than the therapist in charge | |||

| (D) Under medication | Test under medication | Medications that alter the capacity | |||

| * Expectations of the therapists | Evaluation of the patients’ assessments of the intensity of the load |

References

- Pollentier, B.; Irons, S.L.; Benedetto, C.M.; Dibenedetto, A.-M.; Loton, D.; Seyler, R.D.; Tych, M.; Newton, R.A. Examination of the Six Minute Walk Test to Determine Functional Capacity in People with Chronic Heart Failure: A Systematic Review. Cardiopulm. Phys. Ther. J. 2010, 21, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiorina, C.; Vizzardi, E.; Lorusso, R.; Maggio, M.; De Cicco, G.; Nodari, S.; Faggiano, P.; Dei Cas, L. The 6-Min Walking Test Early after Cardiac Surgery. Reference Values and the Effects of Rehabilitation Programme. Eur. J. Cardio-Thorac. Surg. 2007, 32, 724–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ATS Committee on Proficiency Standards for Clinical Pulmonary Function Laboratories. ATS Statement: Guidelines for the Six-Minute Walk Test. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2002, 166, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingle, L.; Shelton, R.J.; Rigby, A.S.; Nabb, S.; Clark, A.L.; Cleland, J.G.F. The Reproducibility and Sensitivity of the 6-Min Walk Test in Elderly Patients with Chronic Heart Failure. Eur. Heart J. 2005, 26, 1742–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdanyar, A.; Aziz, M.M.; Enright, P.L.; Edmundowicz, D.; Boudreau, R.; Sutton-Tyrell, K.; Kuller, L.; Newman, A.B. Association Between 6-Minute Walk Test and All-Cause Mortality, Coronary Heart Disease–Specific Mortality, and Incident Coronary Heart Disease. J. Aging Health 2014, 26, 583–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borg, G. The Borg CR Scales Folder; Borg Perception: Hasselby, Sweden, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Borg, G. Borg’s Perceived Exertion and Pain Scales; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 1998; ISBN 978-0-88011-623-7. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, D.; Stevens, A.; Eijnde, B.O.; Dendale, P. Endurance Exercise Intensity Determination in the Rehabilitation of Coronary Artery Disease Patients: A Critical Re-Appraisal of Current Evidence. Sports Med. 2012, 42, 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.J.; Fan, X.; Moe, S.T. Criterion-Related Validity of the Borg Ratings of Perceived Exertion Scale in Healthy Individuals: A Meta-Analysis. J. Sports Sci. 2002, 20, 873–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bar-Or, O. AGE-RELATED CHANGES IN EXERCISE PERCEPTION. In Physical Work and Effort; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1977; pp. 255–266. ISBN 978-0-08-021373-6. [Google Scholar]

- Cabral, L.L.; Lopes, P.B.; Wolf, R.; Stefanello, J.M.F.; Pereira, G. A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW OF CROSS-CULTURAL ADAPTATION AND VALIDATION OF BORG’S RATING OF PERCEIVED EXERTION SCALE. J. Phys. Educ. 2017, 28, e2853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano-Maldonado, A.; Romero, L.; Femia, P.; Roero, C.; Ruiz, J.; Gutierrez, A. A Learning Protocol Improves the Validity of the Borg 6–20 RPE Scale During Indoor Cycling. Int. J. Sports Med. 2013, 35, 379–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julius, L.M.; Brach, J.S.; Wert, D.M.; VanSwearingen, J.M. Perceived Effort of Walking: Relationship with Gait, Physical Function and Activity, Fear of Falling, and Confidence in Walking in Older Adults with Mobility Limitations. Phys. Ther. 2012, 92, 1268–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sager, M.A.; Dunham, N.C.; Schwantes, A.; Mecum, L.; Halverson, K.; Harlowe, D. Measurement of Activities of Daily Living in Hospitalized Elderly: A Comparison of Self-Report and Performance-Based Methods. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1992, 40, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coull, A.; Pugh, G. Maintaining Physical Activity Following Myocardial Infarction: A Qualitative Study. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2021, 21, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, G. Anstrengungsempfinden und Körperliche Aktivität. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2004, 101, A-1016. [Google Scholar]

- Shea, M.G.; Farris, S.G.; Hutchinson, J.; Headley, S.; Schilling, P.; Pack, Q.R. Effects of Exercise Testing and Cardiac Rehabilitation in Patients with Coronary Heart Disease on Fear and Self-Efficacy of Exercise: A Pilot Study. Int.J. Behav. Med. 2024, 31, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myers, J. Applications of Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing in the Management of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Disease. Int. J. Sports Med. 2005, 26, S49–S55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abreu, A.; Frederix, I.; Dendale, P.; Janssen, A.; Doherty, P.; Piepoli, M.F.; Völler, H.; Davos, C.H.; the Secondary Prevention and Rehabilitation Section of EAPC Reviewers: Ambrosetti Marco. Standardization and Quality Improvement of Secondary Prevention through Cardiovascular Rehabilitation Programmes in Europe: The Avenue towards EAPC Accreditation Programme: A Position Statement of the Secondary Prevention and Rehabilitation Section of the European Association of Preventive Cardiology (EAPC). Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2021, 28, 496–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, J.M.; Strauss, A.L. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications, Inc.: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-1-4129-0643-2. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, H.; Sun, C.; Sun, B.; Chen, X.; Tan, Z. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Relationship between Actual Exercise Intensity and Rating of Perceived Exertion in the Overweight and Obese Population. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, A.E.; Spruit, M.A.; Troosters, T.; Puhan, M.A.; Pepin, V.; Saey, D.; McCormack, M.C.; Carlin, B.W.; Sciurba, F.C.; Pitta, F.; et al. An Official European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society Technical Standard: Field Walking Tests in Chronic Respiratory Disease. Eur. Respir. J. 2014, 44, 1428–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dresing, T.; Pehl, T. Praxisbuch Interview, Transkription & Analyse: Anleitungen und Regelsysteme für qualitativ Forschende; 8. Auflage; Eigenverlag: Marburg, Germany, 2018; ISBN 978-3-8185-0489-2. [Google Scholar]

- Strübing, J. Qualitative Sozialforschung: Eine Komprimierte Einführung; 2., überarbeitete und erweiterte Auflage; De Gruyter Oldenbourg: Berlin, Germany; Boston, MA, USA, 2018; ISBN 978-3-11-052991-3. [Google Scholar]

- Enright, P.L.; McBurnie, M.A.; Bittner, V.; Tracy, R.P.; McNamara, R.; Arnold, A.; Newman, A.B.; Cardiovascular Health Study. The 6-Min Walk Test: A Quick Measure of Functional Status in Elderly Adults. Chest 2003, 123, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inbar, O.; Oren, A.; Scheinowitz, M.; Rotstein, A.; Dlin, R.; Casaburi, R. Normal Cardiopulmonary Responses during Incremental Exercise in 20- to 70-Yr-Old Men. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1994, 26, 538–546. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, B.R.; Slade, M.D.; Kasl, S.V. Longitudinal Benefit of Positive Self-Perceptions of Aging on Functional Health. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2002, 57, P409–P417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wurm, S.; Warner, L.M.; Ziegelmann, J.P.; Wolff, J.K.; Schüz, B. How Do Negative Self-Perceptions of Aging Become a Self-Fulfilling Prophecy? Psychol. Aging 2013, 28, 1088–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velaithan, V.; Tan, M.-M.; Yu, T.-F.; Liem, A.; Teh, P.-L.; Su, T.T. The Association of Self-Perception of Aging and Quality of Life in Older Adults: A Systematic Review. Gerontologist 2024, 64, gnad041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukase, Y.; Murayama, N.; Tagaya, H. The Role of Psychological Autonomy in the Acceptance of Ageing among Community-dwelling Elderly. Psychogeriatrics 2018, 18, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tovel, H.; Carmel, S.; Raveis, V.H. Relationships Among Self-Perception of Aging, Physical Functioning, and Self-Efficacy in Late Life. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2019, 74, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, F.C.; Al-Ansari, S.S.; Biddle, S.; Borodulin, K.; Buman, M.P.; Cardon, G.; Carty, C.; Chaput, J.-P.; Chastin, S.; Chou, R.; et al. World Health Organization 2020 Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 1451–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, G.; Barker, A.L.; Talevski, J.; Ackerman, I.; Ayton, D.R.; Reid, C.; Evans, S.M.; Stoelwinder, J.U.; McNeil, J.J. Do Patients Have a Say? A Narrative Review of the Development of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures Used in Elective Procedures for Coronary Revascularisation. Qual. Life Res. 2018, 27, 1369–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormack, C.; Cullivan, S.; Kehoe, B.; McCaffrey, N.; Gaine, S.; McCullagh, B.; Moyna, N.M.; Hardcastle, S.J. “It Is the Fear of Exercise That Stops Me”—Attitudes and Dimensions Influencing Physical Activity in Pulmonary Hypertension Patients. Pulm. Circ. 2021, 11, 20458940211056509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muotri, R.; Bernik, M.; Lotufo-Neto, F. Misinterpretation of the Borg’s Rating of Perceived Exertion Scale by Patients with Panic Disorder during Ergospirometry Challenge. BMJ Open Sport. Exerc. Med. 2017, 3, e000164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, S.T.; Murphy, B.M.; Rogerson, M.; Grande, M.L.; Hester, R.; Jackson, A.C. Conceptualizing Fear of Progression in Cardiac Patients: Advancing Our Understanding of the Psychological Impact of Cardiac Illness. Heart Mind 2024, 8, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.J.; Morgan, M.D.; Scott, S.; Walters, D.; Hardman, A.E. Development of a Shuttle Walking Test of Disability in Patients with Chronic Airways Obstruction. Thorax 1992, 47, 1019–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, D.J.; Watts, K.; Rankin, S.; Wong, P.; O’Driscoll, J.G. A Comparison of the Shuttle and 6 Minute Walking Tests with Measured Peak Oxygen Consumption in Patients with Heart Failure. J. Sci. Med. Sport. 2001, 4, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raisi, A.; Zerbini, V.; Myers, J.; Piva, T.; Campo, G.; Mazzoni, G.; Grazzi, G.; Mandini, S. A Novel Motivational Approach in the Management of Older Patients With Cardiovascular Disease. J. Cardiopulm. Rehabil. Prev. 2023, 43, 309–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinsen, E.W. Physical Activity in the Prevention and Treatment of Anxiety and Depression. Nord. J. Psychiatry 2008, 62, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Wal, M.H.L.; van Veldhuisen, D.J.; Veeger, N.J.G.M.; Rutten, F.H.; Jaarsma, T. Compliance with Non-Pharmacological Recommendations and Outcome in Heart Failure Patients. Eur. Heart J. 2010, 31, 1486–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbiellini Amidei, C.; Trevisan, C.; Dotto, M.; Ferroni, E.; Noale, M.; Maggi, S.; Corti, M.C.; Baggio, G.; Fedeli, U.; Sergi, G. Association of Physical Activity Trajectories with Major Cardiovascular Diseases in Elderly People. Heart 2022, 108, 360–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, E.A.; Lord, L.M.; Asongwed, E.; Jackson, P.; Johnson-Largent, T.; Jean Baptiste, A.M.; Harris, B.M.; Jeffery, T. Perceptions, Opinions, Beliefs, and Attitudes About Physical Activity and Exercise in Urban-Community-Residing Older Adults. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2020, 11, 215013272092413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchard, D.R.; Langlois, M.-F.; Boisvert-Vigneault, K.; Farand, P.; Paulin, M.; Baillargeon, J.-P. Pilot Study: Can Older Inactive Adults Learn How to Reach the Required Intensity of Physical Activity Guideline? Clin. Interv. Aging 2013, 8, 501–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paula Born, L.; Luana Loss, C.; Robert, J.R.; Andrea Holtz, F.; Gleber, P. A Systematic Review of Validity and Reliability of Perceived Exertion Xcales to Older Adults. Rev. Psicol. Deporte (J. Sport Psychol.) 2021, 29, 74–89. [Google Scholar]

- Eston, R.; Connolly, D. The Use of Ratings of Perceived Exertion for Exercise Prescription in Patients Receiving Beta-Blocker Therapy. Sports Med. 1996, 21, 176–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morishita, S.; Tsubaki, A.; Nakamura, M.; Nashimoto, S.; Fu, J.B.; Onishi, H. Rating of Perceived Exertion on Resistance Training in Elderly Subjects. Expert. Rev. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2019, 17, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, C.G.; Nielsen, C.V.; Lynggaard, V.; Zwisler, A.D.; Maribo, T. Cardiac Rehabilitation: Pedagogical Education Strategies Have Positive Effect on Long-Term Patient-Reported Outcomes. Health Educ. Res. 2023, 38, 597–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Measurement |

|---|---|

| N (male) | 10 (6) |

| Mean age, years (range) | 74.5/(67–82) |

| Mean BMI, kg/m2 (range) | 23/(18–29) |

| Time to the acute event, days in preceding hospital, mean (range) | 11.5 (8–20) |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 4 |

| NSTEMI | 1 |

| STEMI | 3 |

| Condition after reanimation | 1 |

| Degree of coronary heart disease | |

| 2-vessel disease, n | 6 |

| 3-vessel disease, n | 4 |

| Intervention | |

| PTCA with stent | 4 |

| Coronary bypass graft surgery | 5 |

| Comorbidities | |

| Heart failure | 1 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 4 |

| Arterial hypertension | 5 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 4 |

| Patients with betablockers | 10 |

| Civil status | |

| Living in partnership | 5 |

| Living alone | 5 |

| Variable | Measurement |

|---|---|

| Mean distance, m (range) | 401 (168–553) |

| Percentage of predicted value, m (range) | 80 (37–101) |

| Difference between heart rate before/after test, median (minimum/maximum) | 15/(1–35) |

| Percentage of predicted value, heart rate (range) | 65 (41–72) |

| Value of perceived exertion (score 0–10) | |

| Value | Number |

| 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 1 |

| 3 | 1 |

| 4 | 3 |

| 5 | 4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Büsching, G.; Schmid, J.-P. 6-Minute Walk Test: Exploring Factors Influencing Perceived Intensity in Older Patients Undergoing Cardiac Rehabilitation—A Qualitative Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 735. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070735

Büsching G, Schmid J-P. 6-Minute Walk Test: Exploring Factors Influencing Perceived Intensity in Older Patients Undergoing Cardiac Rehabilitation—A Qualitative Study. Healthcare. 2025; 13(7):735. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070735

Chicago/Turabian StyleBüsching, Gilbert, and Jean-Paul Schmid. 2025. "6-Minute Walk Test: Exploring Factors Influencing Perceived Intensity in Older Patients Undergoing Cardiac Rehabilitation—A Qualitative Study" Healthcare 13, no. 7: 735. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070735

APA StyleBüsching, G., & Schmid, J.-P. (2025). 6-Minute Walk Test: Exploring Factors Influencing Perceived Intensity in Older Patients Undergoing Cardiac Rehabilitation—A Qualitative Study. Healthcare, 13(7), 735. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070735