Stress as a Risk Factor for Informal Caregiver Burden

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Risk Factors of the Caregiver Burden

1.2. Other Socio-Demographic Variables Influencing Caregiving Status

1.3. The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instrument

2.3. Procedure

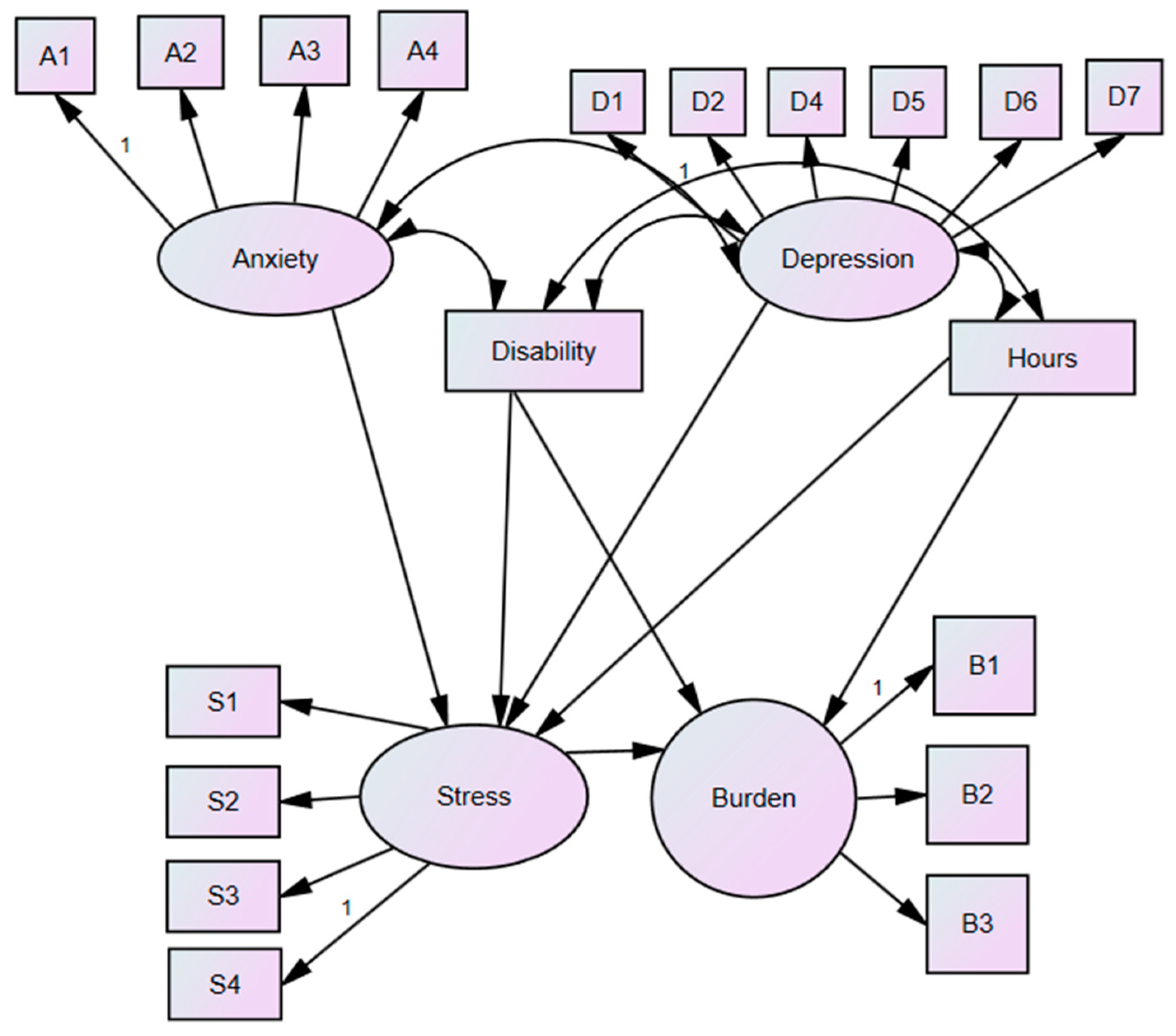

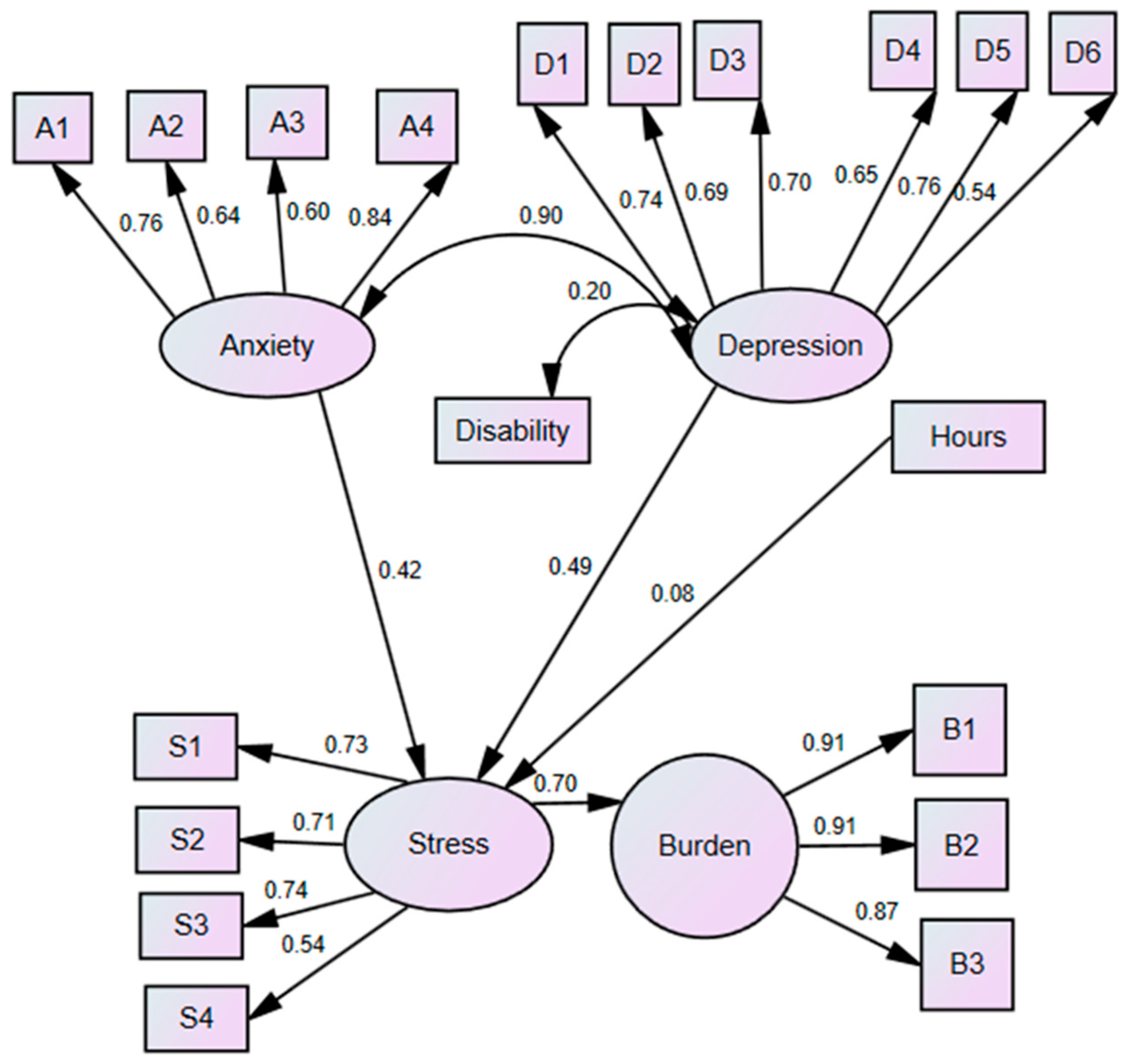

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics of the Risk Variables Measured in Caregivers

3.2. Correlations Among Variables

3.3. Model SEM

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations and Future Directions

4.2. Practical Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Sone, T.; Nakaya, N.; Tomata, Y.; Nakaya, K.; Hoshi, M.; Tsuji, I. Spouse’s functional disability and mortality: The Ohsaki Cohort 2006 Study. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2019, 19, 774–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. (n.d.). Caregiver. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Kim, B.; Wister, A.; O’dea, E.; Mitchell, B.A.; Li, L.; Kadowaki, L. Roles and experiences of informal caregivers of older adults in community and healthcare system navigation: A scoping review. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e077641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del-Pino-Casado, R.; Priego-Cubero, E.; López-Martínez, C.; Orgeta, V. Subjective caregiver burden and anxiety in informal caregivers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0247143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobinac, A.; van Exel, N.J.; Rutten, F.F.; Brouwer, W.B. Caring for and caring about: Disentangling the caregiver effect and the family effect. J. Health Econ. 2010, 29, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzahrani, M.; Alfahaid, F.; Almansour, M.; Alghamdi, T.; Ansari, T.; Sami, W.; Otaibi, T.; Humayn, A.; Enezi, M. Prevalence of generalized anxiety disorder and major depression in health-care givers of disabled patients in Majmaah and Shaqra cities, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Health Sci. 2017, 11, 9–13. [Google Scholar]

- Felipe, S.; Oliveira, C.; Silva, C.; Mendes, P.N.; Carvalho, K.M.; Lopes Silva-Júnior, F.; Figueiredo, M. Anxiety and depression in informal caregivers of dependent elderly people: An analytical study. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2020, 73 (Suppl. S1), e20190851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.G.; Song, S.W.; Kim, S.H.; Kang, Y.J.; Kim, Y.R.; Eun, Y. Fatigue and Mental Status of Caregivers of Severely Chronically Ill Patients. Pain Res. Manag. 2020, 2020, 6372857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polenick, C.A.; DePasquale, N. Predictors of Secondary Role Strains Among Spousal Caregivers of Older Adults with Functional Disability. Gerontologist 2019, 59, 486–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshammari, S.A.; Alzahrani, A.A.; Alabduljabbar, K.A.; Aldaghri, A.A.; Alhusainy, Y.A.; Khan, M.A.; Alshuwaier, R.A.; Kariz, I.N. The burden perceived by informal caregivers of the elderly in Saudi Arabia. J. Fam. Community Med. 2017, 24, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, C.M.; Maccauro, G.; Fulcheri, M. Psychological stress and cancer. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2011, 24, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unson, C.; Njoku, A.; Bernard, S.; Agbalenyo, M. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Chronic Stress among Male Caregivers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurtovenko, K.; Fladeboe, K.M.; Galtieri, L.R.; King, K.; Friedman, D.; Compas, B.; Breiger, D.; Lengua, L.; Keim, M.; Kawamura, J.; et al. Stress and psychological adjustment in caregivers of children with cancer. Health Psychol. 2021, 40, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cejalvo, E.; Martí-Vilar, M.; Merino-Soto, C.; Aguirre-Morales, M.T. Caregiving Role and Psychosocial and Individual Factors: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riffin, C.; Van Ness, P.H.; Wolff, J.L.; Fried, T. Multifactorial Examination of Caregiver Burden in a National Sample of Family and Unpaid Caregivers. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2019, 67, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güven Baysal, Ş.; Çorabay, S. Caregiver Burden and Depression in Parents of Children with Chronic Diseases. Turk. Arch. Pediatr. 2024, 59, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattos, M.K.; Bernacchi, V.; Shaffer, K.M.; Gallagher, V.; Seo, S.; Jepson, L.; Manning, C. Sleep and Caregiver Burden Among Caregivers of Persons Living with Dementia: A Scoping Review. Innov. Aging 2024, 8, igae005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCurley, J.L.; Funes, C.J.; Zale, E.L.; Lin, A.; Jacobo, M.; Jacobs, J.M.; Salgueiro, D.; Tehan, T.; Rosand, J.; Vranceanu, A.M. Preventing Chronic Emotional Distress in Stroke Survivors and Their Informal Caregivers. Neurocritical Care 2019, 30, 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobedo-Aedo, M.J. Anxiety, depression, and stress in informal caregivers: A longitudinal study. J. Aging Health 2025, 37, 45–60. [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart, M.; Sörensen, S. Differences between caregivers and non caregivers in psychological health and physical health: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Aging 2003, 18, 250–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovibond, P.F.; Lovibond, S.H. The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav. Res. Ther. 1995, 33, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiol-DeRoque, M.A.; Serrano-Ripoll, M.J.; Jiménez, R.; Zamanillo-Campos, R.; Yáñez-Juan, A.M.; Bennasar-Veny, M.; Leiva, A.; Gervilla, E.; García-Buades, M.E.; García-Toro, M.; et al. A Mobile Phone-Based Intervention to Reduce Mental Health Problems in Health Care Workers During the COVID-19 Pandemic (PsyCovidApp): Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2021, 9, e27039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gort, A.M.; March, J.; Gómez, X.; de Miguel, M.; Mazarico, S.; Ballesté, J. Escala de Zarit reducida en cuidados paliativos [Short Zarit scale in palliative care]. Med. Clin. 2005, 124, 651–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. Psychometric Theory, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Manzano, A. Introducción a los modelos de ecuaciones estructurales. Metodol. Investig. Salud Méd. 2018, 7, 67–72. [Google Scholar]

- Medrano, L.A.; Muñoz-Navarro, R. Aproximación conceptual y práctica a los Modelos de Ecuaciones Estructurales. Rev. Digit. Investig. Docencia Univ. 2017, 11, 219–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cut-off criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criterio versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H.W.; Hau, K.-T.; Wen, Z. In search of golden rules: Comment on hypothesis-testing approaches to setting cutoff values for fit indexes and dangers in overgeneralizing Hu and Bentler’s (1999) findings. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 2004, 11, 320–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, L.M.; Wilson, S.J.; Madison, A.A.; Prakash, R.S.; Burd, C.E.; Rosko, A.E.; Kiecolt-Glaser, J.K. Understanding the health effects of caregiving stress: New directions in molecular aging. Ageing Res. Rev. 2023, 92, 102096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, B.; Schulz, R. Family caregivers’ strains: Comparative analysis of cancer caregiving with dementia, diabetes, and frail elderly caregiving. J. Aging Health 2020, 32, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losada, A.; Márquez-González, M.; Romero-Moreno, R.; López, J. Development and validation of the Experiential Avoidance in Caregiving Questionnaire (EACQ). Aging Ment. Health 2014, 18, 897–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baishya, J. Caregiver Burden and Stress in Caregivers of Stroke Survivors: Relevant but Neglected. Ann. Indian Acad. Neurol. 2024, 27, 7–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.J.; Kim, Y.; Shamburek, R.; Ross, A.; Yang, L.; Bevans, M.F. Caregiving stress and burden associated with cardiometabolic risk in family caregivers of individuals with cancer. Stress 2022, 25, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelman, R.D.; Tmanova, L.L.; Delgado, D.; Dion, S.; Lachs, M.S. Caregiver burden: A clinical review. JAMA 2014, 311, 1052–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Heffernan, C.; Tan, J. Caregiver burden: A concept analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Sci. 2020, 7, 438–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gérain, P.; Zech, E. Informal Caregiver Burnout? Development of a Theoretical Framework to Understand the Impact of Caregiving. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A.; Lemieux, C.; Kim, Y.K.; Ainsworth, L.; Bardales, R.; Trahan, J.; Wilks, S. Loneliness, Anxiety and Depression Among Caregivers of Persons with Dementia: Mediating Effect Of Self-Efficacy. Innov. Aging 2023, 7 (Suppl. S1), 1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, N.E.; Hoben, M.; Amuah, J.E.; Hogan, D.B.; Baumbusch, J.; Gruneir, A.; Chamberlain, S.A.; Griffith, L.E.; McGrail, K.M.; Corbett, K.; et al. Prevalence and correlates of anxiety and depression in caregivers to assisted living residents during COVID-19: A cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Alberca, J.M.; Lara, J.P.; Berthier, M.L. Anxiety and depression in caregivers of patients with dementia: A longitudinal study. Aging Ment. Health 2021, 25, 1123–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acoba, E.F. Social support and mental health: The mediating role of perceived stress. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1330720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southwick, S.M.; Bonanno, G.A.; Masten, A.S.; Panter-Brick, C.; Yehuda, R. Resilience definitions, theory, and challenges: Interdisciplinary perspectives. Eur. J. Psychotr. 2014, 5, 25338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 3rd ed.; The Guildford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Boomsma, A.; Hoogland, J.J. The robustness of LISREL modeling revisited. In Structural Equation Modeling: Present and Future; En, R., Cudeck, R., Toit, S.D., Sörbom, D., Eds.; Scientific Software International: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 2011; pp. 139–168. [Google Scholar]

- Roth, D.L.; Fredman, L.; Haley, W.E. Informal caregiving and its impact on health: A reappraisal from population-based studies. Gerontologist 2015, 55, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esparza-Reig, J. La conducta prosocial como factor protector de los problemas de adicción al juego en universitarios. Rev. Digit. Investig. Docencia Univ. 2020, 14, e1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobb, S. Social support as a moderator of life stress. Psychosom. Med. 1976, 38, 300–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 202 | 58.7 |

| Male | 142 | 41.3 |

| Hours of care | ||

| 1–56 h | 298 | 86.6 |

| 57–112 h | 15 | 4.4 |

| 113–168 h | 31 | 9 |

| Level of disability | ||

| Low disability | 60 | 17.4 |

| Moderate disability | 175 | 50.9 |

| Severe disability | 109 | 31.7 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Caucasian | 312 | 90.7 |

| Other | 15 | 4.4 |

| Prefer nor to answer | 17 | 4.9 |

| Education Level | ||

| No studies | 10 | 2.9 |

| Primary studies | 61 | 17.7 |

| Secondary studies | 131 | 38.1 |

| University studies | 109 | 31.7 |

| Post-university studies (Master’s, PhD, etc.) | 26 | 7.6 |

| Prefer not to answer | 7 | 2.0 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 59 | 17.2 |

| Married | 186 | 54.1 |

| In relationship | 64 | 18.6 |

| Separated/Divorced | 27 | 7.8 |

| Widowed | 3 | 0.8 |

| Prefer not to answer | 5 | 1.5 |

| Variable | M | SD | Min. | Max. | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | 5.25 | 3.67 | 0 | 20 | 0.644 | 0.129 |

| Depression | 5.67 | 4.04 | 0 | 21 | 0.754 | 0.149 |

| Stress | 8.05 | 3.72 | 0 | 20 | 0.413 | 0.194 |

| Subjective Burden (ZBI-7) | 19.14 | 6.57 | 2 | 35 | 0.161 | −0.309 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Stress | r | - | |||||

| p-value | - | ||||||

| N | - | ||||||

| 2. Depression | r | 0.713 ** | - | ||||

| p-value | 0.000 | - | |||||

| N | 344 | - | |||||

| 3. Anxiety | r | 0.733 ** | 0.760 ** | - | |||

| p-value | 0.000 | 0.000 | - | ||||

| N | 344 | 344 | - | ||||

| 4. Burden (ZBI-7) | r | 0.636 ** | 0.550 ** | 0.542 ** | - | ||

| p-value | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | - | |||

| N | 344 | 344 | 344 | - | |||

| 5. Level of disability | r | 0.203 ** | 0.174 ** | 0.120 * | 0.232 ** | - | |

| p-value | 0.001 | 0.005 | 0.039 | 0.000 | - | ||

| N | 343 | 343 | 343 | 343 | - | ||

| 6. Hours of care | r | 0.164 ** | 0.091 | 0.090 | 0.156 ** | 0.114 ** | - |

| p-value | 0.005 | 0.131 | 0.136 | 0.005 | 0.035 | - | |

| N | 344 | 344 | 344 | 344 | 343 | - |

| Variable | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | ||

| A1 | 0.546 | 0.228 |

| A2 | 1.023 | 0.680 |

| A3 | 0.825 | 0.206 |

| A4 | 0.770 | −0.0051 |

| Depression | ||

| D1 | 0.617 | 0.333 |

| D2 | 1.049 | 0.681 |

| D3 | 0.847 | 0.179 |

| D4 | 1.208 | 0.681 |

| D5 | 0.515 | −0.035 |

| D6 | 0.809 | 0.004 |

| D7 | 0.609 | 0.224 |

| Stress | ||

| S1 | 0.506 | 0.098 |

| S2 | 0.414 | 0.145 |

| S3 | 0.515 | 0.359 |

| S4 | 0.653 | 0.511 |

| Burden | ||

| B1 | 0.039 | −0.227 |

| B2 | 0.194 | −0.473 |

| B3 | 0.302 | −0.599 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cejalvo, E.; Martí-Vilar, M.; Gisbert-Pérez, J.; Badenes-Ribera, L. Stress as a Risk Factor for Informal Caregiver Burden. Healthcare 2025, 13, 731. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070731

Cejalvo E, Martí-Vilar M, Gisbert-Pérez J, Badenes-Ribera L. Stress as a Risk Factor for Informal Caregiver Burden. Healthcare. 2025; 13(7):731. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070731

Chicago/Turabian StyleCejalvo, Elena, Manuel Martí-Vilar, Júlia Gisbert-Pérez, and Laura Badenes-Ribera. 2025. "Stress as a Risk Factor for Informal Caregiver Burden" Healthcare 13, no. 7: 731. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070731

APA StyleCejalvo, E., Martí-Vilar, M., Gisbert-Pérez, J., & Badenes-Ribera, L. (2025). Stress as a Risk Factor for Informal Caregiver Burden. Healthcare, 13(7), 731. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070731