Recurrent Giant Ovarian Cysts in Biological Sisters: 2 Case Reports and Literature Review—Giant Ovarian Cysts in 2 Sisters

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Cases Presentation

2.1. Case 1

2.1.1. Clinical Presentation

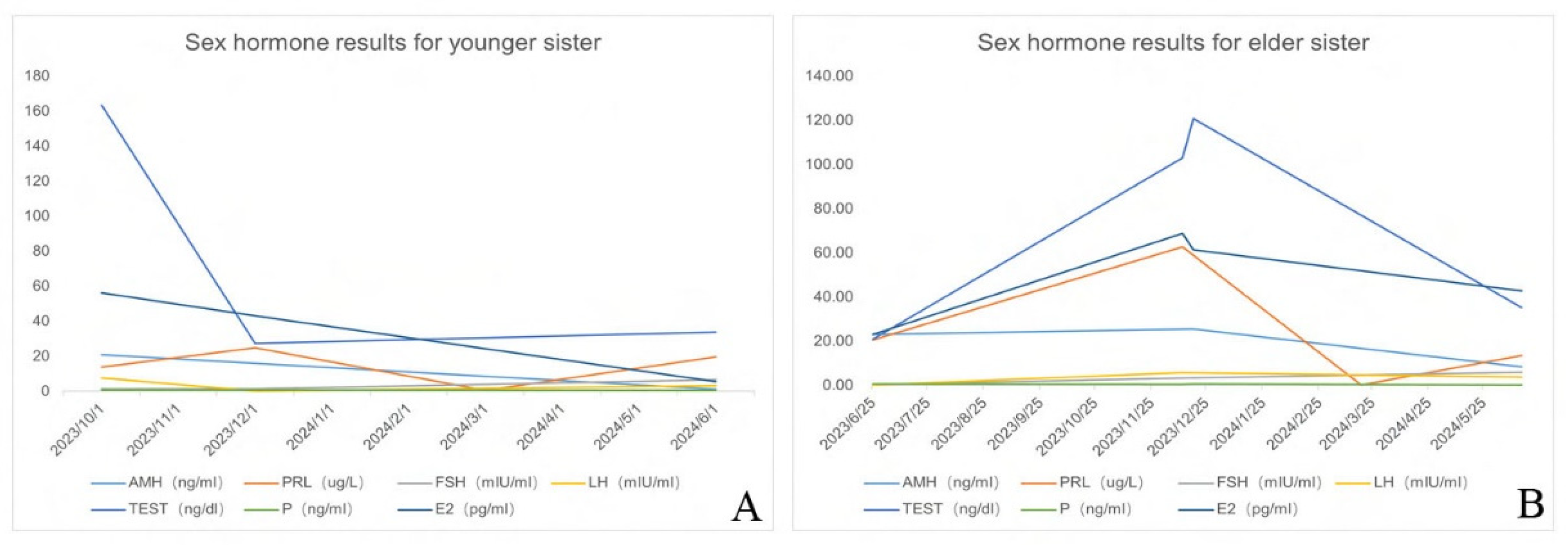

2.1.2. Diagnostic Workup

2.1.3. Treatment and Outcomes

2.2. Case 2

2.2.1. Clinical Presentation

2.2.2. Diagnostic Workup

2.2.3. Treatment and Outcomes

2.2.4. Follow-Up

3. Discussion

3.1. Case Analysis

3.2. Analysis of the Causes of Recurrent Ovarian Cysts

3.2.1. Cystic Granulosa Cell Tumors

3.2.2. Aromatase Deficiency (AD) and Ovarian Luteinized Cysts

3.2.3. Hyperprolactinemia and Polycystic Ovarian Changes

3.2.4. Pituitary Gonadotropinoma and Ovarian Hyperstimulation Syndrome

3.2.5. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS)

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Watkins, J.C.; Young, R.H. Follicle Cysts of the Ovary: A Report of 30 Cases of a Common Benign Lesion Emphasizing its Unusual Clinical and Pathologic Aspects. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. Off. J. Int. Soc. Gynecol. Pathol. 2021, 40, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mobeen, S.; Apostol, R. Ovarian Cyst. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi, T.; Ogawa, Y.; Ito, K.; Watanabe, M.; Tominaga, T. Follicle-stimulating hormone-secreting pituitary adenoma manifesting as recurrent ovarian cysts in a young woman--latent risk of unidentified ovarian hyperstimulation: A case report. BMC Res. Notes 2013, 6, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhary, H.; Patel, J.; Jain, N.K.; Joshi, R. The role of polymorphism in various potential genes on polycystic ovary syndrome susceptibility and pathogenesis. J. Ovarian Res. 2021, 14, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vambergue, A.; Lautier, C.; Valat, A.S.; Cortet-Rudelli, C.; Grigorescu, F.; Dewailly, D. Follow-up study of two sisters with type A syndrome of severe insulin resistance gives a new insight into PCOS pathogenesis in relation to puberty and pregnancy outcome: A case report. Hum. Reprod. 2006, 21, 1274–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedenk, J.; Vrtačnik-Bokal, E.; Virant-Klun, I. The role of anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) in ovarian disease and infertility. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2020, 37, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Ledesma, L.; Díaz Ramos, J.A.; Trujillo Hernández, A. Polycystic ovary syndrome induced by exposure to testosterone propionate and effects of sympathectomy on the persistence of the syndrome. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2017, 15, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, W.-W.; Huang, C.-C.; Chen, Y.-R.; Yu, D.-Q.; Jin, M.; Feng, C. The effect of medication on serum anti-müllerian hormone (AMH) levels in women of reproductive age: A meta-analysis. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2022, 22, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, Y.; Eijkemans, M.J.C.; Coelingh Bennink, H.J.T.; Blankenstein, M.A.; Fauser, B.C.J.M. The effect of combined oral contraception on testosterone levels in healthy women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum. Reprod. Update 2014, 20, 76–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyraz, B.; Watkins, J.C.; Soubeyran, I.; Bonhomme, B.; Croce, S.; Oliva, E.; Young, R.H. Cystic Granulosa Cell Tumors of the Ovary: An Analysis of 80 Cases of an Often Diagnostically Challenging Entity. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2022, 146, 1450–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulun, S.E. Aromatase and estrogen receptor α deficiency. Fertil. Steril. 2014, 101, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Tian, Q. Diagnostic challenges and management advances in cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase deficiency, a rare form of congenital adrenal hyperplasia, with 46, XX karyotype. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1226387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unsal, V. Aromatase Deficiency BT—Genetic Syndromes: A Comprehensive Reference Guide. In Genetic Syndromes; Rezaei, N., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.A.; Sharma, R.; Ata, F.; Khalil, S.K.; Aldien, A.S.; Hasnain, M.; Sadiq, A.; Bilal, A.B.I.; Mirza, W. Systematic review of the association between thyroid disorders and hyperprolactinemia. Thyroid. Res. 2025, 18, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baranowski, E.; Högler, W. An unusual presentation of acquired hypothyroidism: The Van Wyk-Grumbach syndrome. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2012, 166, 537–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastnak, L.; Herman, R.; Ferjan, S.; Janež, A.; Jensterle, M. Prolactin in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Metabolic Effects and Therapeutic Prospects. Life 2023, 13, 2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halupczok, J.; Kluba-Szyszka, A.; Bidzińska-Speichert, B.; Knychalski, B. Ovarian Hyperstimulation Caused by Gonadotroph Pituitary Adenoma--Review. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. Off. Organ Wroclaw Med. Univ. 2015, 24, 695–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capatina, C.; Hanzu, F.A.; Hinojosa-Amaya, J.M.; Fleseriu, M. Medical treatment of functional pituitary adenomas, trials and tribulations. J. Neurooncol. 2024, 168, 197–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, R.; DePetrillo, A.D.; Thomas, G. Clinical review of adult granulosa cell tumors of the ovary. Gynecol. Oncol. 1995, 56, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salenave, S.; Gatta, B.; Pecheur, S.; San-Galli, F.; Visot, A.; Lasjaunias, P.; Roger, P.; Berge, J.; Young, J.; Tabarin, A.; et al. Pituitary Magnetic Resonance Imaging Findings Do Not Influence Surgical Outcome in Adrenocorticotropin-Secreting Microadenomas. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2004, 89, 3371–3376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntali, G.; Capatina, C. Updating the Landscape for Functioning Gonadotroph Tumors. Medicina 2022, 58, 1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, K.L.; DuBose, L.E. The role of androgens in microvascular endothelial dysfunction in polycystic ovary syndrome: Does size matter? J. Physiol. 2019, 597, 2829–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teede, H.J.; Tay, C.T.; Laven, J.; Dokras, A.; Moran, L.J.; Piltonen, T.T.; Costello, M.F.; Boivin, J.; Redman, L.M.; Boyle, J.A.; et al. Recommendations from the 2023 International Evidence-based Guideline for the Assessment and Management of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2023, 120, 767–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacob, S.L.; Field, H.P.; Calder, N.; Picton, H.M.; Balen, A.H.; Barth, J.H. Anti-Müllerian hormone reflects the severity of polycystic ovary syndrome. Clin. Endocrinol. 2017, 86, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhide, P.; Homburg, R. Anti-Müllerian hormone and polycystic ovary syndrome. Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2016, 37, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pea, J.; Bryan, J.; Wan, C.; Oldfield, A.L.; Ganga, K.; Carter, F.E.; Johnson, L.M.; Lujan, M.E. Ultrasonographic criteria in the diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome: A systematic review and diagnostic meta-analysis. Hum. Reprod. Update 2024, 30, 109–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Wattar, B.H.; Fisher, M.; Bevington, L.; Talaulikar, V.; Davies, M.; Conway, G.; Yasmin, E. Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Diagnosis and Management of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Quality Assessment Study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 106, 2436–2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/polycystic-ovary-syndrome (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Jahanfar, S.; Eden, J.A.; Warren, P.; Seppälä, M.; Nguyen, T.V. A twin study of polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil. Steril. 1995, 63, 478–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legro, R.S.; Bentley-Lewis, R.; Driscoll, D.; Wang, S.C.; Dunaif, A. Insulin resistance in the sisters of women with polycystic ovary syndrome: Association with hyperandrogenemia rather than menstrual irregularity. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2002, 87, 2128–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Alfonso, J.C.; Hernández Martín, S.; Ayuso González, L.; Pérez Martínez, A. An Adolescent with a Giant Ovarian Cyst and Hyperandrogenism: Case Report. Case Rep. Endocrinol. 2025, 2025, 6652681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Maurya, R.; Sen, G.; Srivastava, H. Atypical Presentation of a Giant Hemorrhagic Ovarian Cyst. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. India. 2022, 72 (Suppl. 2), 435–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malini, N.A.; Roy George, K. Evaluation of different ranges of LH:FSH ratios in polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS)—Clinical based case control study. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2018, 260, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoudi, Z.; Araghi, F.; Vahedi, M.; Mokhtari, N.; Gheisari, M. Prolactin Level in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS): An approach to the diagnosis and management. Acta Biomed. 2021, 92, e2021291. [Google Scholar]

- Oguz, S.H.; Yildiz, B.O. An Update on Contraception in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 36, 296–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ESHRE Capri Workshop Group. Ovarian and endometrial function during hormonal contraception. Hum. Reprod. 2001, 16, 1527–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Case 1 (Younger Sister) | Case 2 (Elder Sister) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 16 | 19 |

| BMI | 22.86 kg/m2 | 22.49 kg/m2 |

| Hyperandrogenism signs | Distended abdomen, dense pubic hair and a thickened clitoris | Facial acne, dense body hair, Adam’s apple-like prominence, distended, abdomen, dense pubic hair and enlarged clitoris |

| Imaging findings | Large ovarian cystic mass with a maximum diameter of about 35 cm | Large ovarian cystic mass with a maximum diameter of 43 cm |

| Ovarian tumor markers | Normal | Normal |

| Pelvic laparotomy findings | Large cyst in the right ovary and an 8 cm cyst in the left ovary | Large cyst in the right ovary and a smaller 11 cm cyst in the left ovary |

| Pathological diagnoses | Right ovarian serous cystadenoma and a left ovarian follicular cyst | Right ovarian follicular cyst and a left ovarian mature teratoma |

| Hormonal anomalies | Increased AMH, testosterone, and prolactin Decreased LH and FSH | Increased AMH and testosterone Decreased LH and FSH |

| Recurrence of the ovarian cysts after surgery | Yes | Yes |

| Sustained response to contraceptives | Yes | Yes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, S.; Zeng, Q.; Hu, L.; Zeng, B.; Wu, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhou, M.; Gan, X. Recurrent Giant Ovarian Cysts in Biological Sisters: 2 Case Reports and Literature Review—Giant Ovarian Cysts in 2 Sisters. Healthcare 2025, 13, 656. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13060656

Liu S, Zeng Q, Hu L, Zeng B, Wu Y, Wang C, Zhou M, Gan X. Recurrent Giant Ovarian Cysts in Biological Sisters: 2 Case Reports and Literature Review—Giant Ovarian Cysts in 2 Sisters. Healthcare. 2025; 13(6):656. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13060656

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Shuaibin, Qianru Zeng, Lina Hu, Biao Zeng, Yi Wu, Chenxi Wang, Min Zhou, and Xiaoling Gan. 2025. "Recurrent Giant Ovarian Cysts in Biological Sisters: 2 Case Reports and Literature Review—Giant Ovarian Cysts in 2 Sisters" Healthcare 13, no. 6: 656. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13060656

APA StyleLiu, S., Zeng, Q., Hu, L., Zeng, B., Wu, Y., Wang, C., Zhou, M., & Gan, X. (2025). Recurrent Giant Ovarian Cysts in Biological Sisters: 2 Case Reports and Literature Review—Giant Ovarian Cysts in 2 Sisters. Healthcare, 13(6), 656. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13060656