Patient Perspectives on Healthcare Utilization During the COVID-19 Pandemic in People with Multiple Sclerosis—A Longitudinal Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Recruitment and Survey Periods

2.2. The Survey Design

2.3. Statistical Methods

3. Results

3.1. Participants

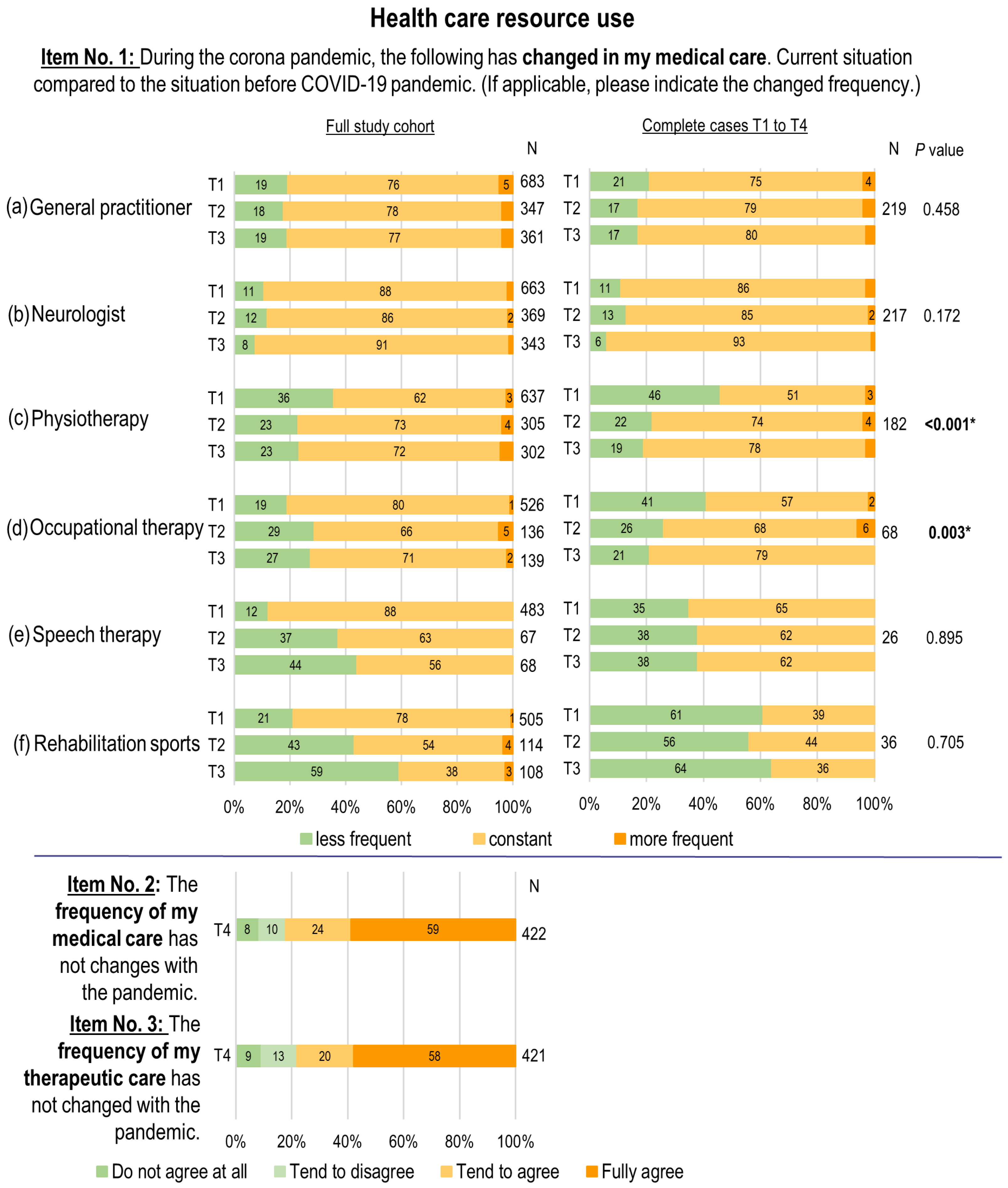

3.2. Healthcare Resource Use

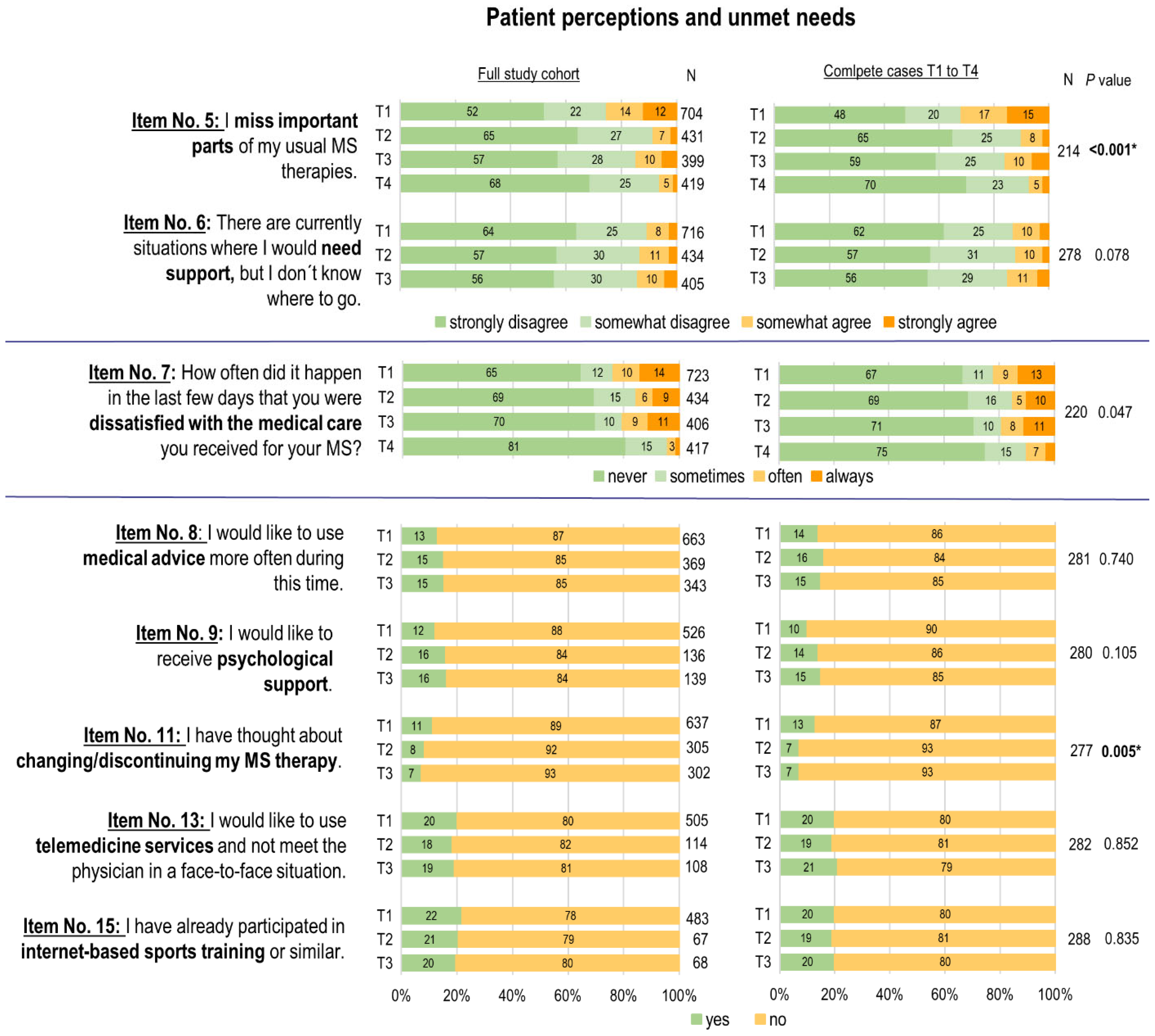

3.3. Patient Perceptions and Unmet Needs

3.4. Evaluation of Influencing Factors in Relation to Four Key Items at T1 in April 2020

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Domains | No. | Item | Survey Periods (T) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

| Healthcare resource use | 1 | During the corona pandemic (current situation), the following has changed in my medical care. (If applicable, please indicate the changed frequency). Compared to before the pandemic, visits are less frequent/same/more frequent: (a) general practitioner, (b) neurologist, (c) physical therapy, (d) occupational therapy, (e) speech therapy, (f) rehabilitation sports. | x | x | x | |

| 2 | The frequency of my medical care (general practitioner, neurologist) has not changed with the pandemic. | x | ||||

| 3 | The frequency of my therapeutic care (physiotherapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy, rehabilitation sports) has not changed with the pandemic. | x | ||||

| 4 | How often in the last three days have you been dissatisfied with your therapeutic care (physiotherapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy, rehabilitation sports)? | x | ||||

| Perception and unmet needs | 5 | I miss important parts of my usual MS therapies. | x | x | x | x |

| 6 | There are currently situations where I would need support, but I do not know where to go. | x | x | x | ||

| 7 | How often did it happen in the last few days that you were dissatisfied with the medical care you received for your MS? | x | x | x | x | |

| 8 | I would like to use medical advice more often during this time. | x | x | x | ||

| 9 | I would like to receive psychological support. | x | x | x | ||

| 10 | I have received or am receiving psychological support. | x | ||||

| 11 | I have thought about changing/discontinuing my MS therapy. | x | x | x | ||

| 12 | I stopped/changed my MS therapy because of the coronavirus. | x | ||||

| 13 | I would like to use telemedicine services and not meet the physician in a face-to-face situation. | x | x | x | ||

| 14 | I have been using telemedicine services so that I do not have to meet my physician in a face-to-face situation. | x | ||||

| 15 | I have already participated in internet-based sports training or similar. | x | x | x | ||

References

- Prosperini, L.; Arrambide, G.; Celius, E.G.; Goletti, D.; Killestein, J.; Kos, D.; Lavorgna, L.; Louapre, C.; Sormani, M.P.; Stastna, D.; et al. COVID-19 and Multiple Sclerosis: Challenges and Lessons for Patient Care. Lancet Reg. Health–Eur. 2024, 44, 100979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabresi, P.A. Diagnosis and Management of Multiple Sclerosis. Am. Fam. Physician 2004, 70, 1935–1944. [Google Scholar]

- The Multiple Sclerosis International Federation Atlas of MS 3rd Edition: Mapping Multiple Sclerosis around the World. Available online: https://www.msif.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Atlas-3rd-Edition-Epidemiology-report-EN-updated-30-9-20.pdf (accessed on 6 November 2024).

- Wallin, M.T.; Culpepper, W.J.; Nichols, E.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Gebrehiwot, T.T.; Hay, S.I.; Khalil, I.A.; Krohn, K.J.; Liang, X.; Naghavi, M.; et al. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Multiple Sclerosis 1990–2016: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. Neurol. 2019, 18, 269–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.H.; Goverover, Y.; Botticello, A.; DeLuca, J.; Genova, H.M. Healthcare Disruptions and Use of Telehealth Services Among People with Multiple Sclerosis During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2022, 103, 1379–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbadessa, G.; Lavorgna, L.; Trojsi, F.; Coppola, C.; Bonavita, S. Understanding and Managing the Impact of the Covid-19 Pandemic and Lockdown on Patients with Multiple Sclerosis. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2021, 21, 731–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moss, B.P.; Mahajan, K.R.; Bermel, R.A.; Hellisz, K.; Hua, L.H.; Hudec, T.; Husak, S.; McGinley, M.P.; Ontaneda, D.; Wang, Z.; et al. Multiple Sclerosis Management during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Mult. Scler. J. 2020, 26, 1163–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abasıyanık, Z.; Kurt, M.; Kahraman, T. COVID-19 and Physical Activity Behaviour in People with Neurological Diseases: A Systematic Review. J. Dev. Phys. Disabil. 2022, 34, 987–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenk, J.; Voigt, I.; Inojosa, H.; Schlieter, H.; Ziemssen, T. Building Digital Patient Pathways for the Management and Treatment of Multiple Sclerosis. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1356436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orschiedt, J.; Jacyshyn-Owen, E.; Kahn, M.; Jansen, S.; Joschko, N.; Eberl, M.; Schneeweiss, S.; Friedrich, B.; Ziemssen, T. The Influence of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Prescription of Multiple Sclerosis Medication in Germany. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 158, 114129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voigt, I.; Inojosa, H.; Wenk, J.; Akgün, K.; Ziemssen, T. Building a Monitoring Matrix for the Management of Multiple Sclerosis. Autoimmun. Rev. 2023, 22, 103358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portaccio, E.; Fonderico, M.; Hemmer, B.; Derfuss, T.; Stankoff, B.; Selmaj, K.; Tintore, M.; Amato, M.P. Impact of COVID-19 on Multiple Sclerosis Care and Management: Results from the European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis Survey. Mult. Scler. J. 2022, 28, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manacorda, T.; Bandiera, P.; Terzuoli, F.; Ponzio, M.; Brichetto, G.; Zaratin, P.; Bezzini, D.; Battaglia, M.A. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Persons with Multiple Sclerosis: Early Findings from a Survey on Disruptions in Care and Self-Reported Outcomes. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2021, 26, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altieri, M.; Capuano, R.; Bisecco, A.; D’Ambrosio, A.; Risi, M.; Cavalla, P.; Vercellino, M.; Annovazzi, P.; Zaffaroni, M.; De Stefano, N.; et al. Quality of Care Provided by Multiple Sclerosis Centers during Covid-19 Pandemic: Results of an Italian Multicenter Patient-Centered Survey. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2023, 77, 104870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogel, A.C.; Schmidt, H.; Loud, S.; McBurney, R.; Mateen, F.J. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Health Care of >1000 People Living with Multiple Sclerosis: A Cross-Sectional Study. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2020, 46, 102512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Learmonth, Y.C.; Bhoyroo, R.; Gibbs, L.; Kermode, A.; Walker, D.; Marck, C.H. Multiple Sclerosis and COVID-19: Health and Healthcare Access, Health Information and Consumer Co-Created Strategies for Future Access at Times of Crisis. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2024, 87, 105691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colais, P.; Cascini, S.; Balducci, M.; Agabiti, N.; Davoli, M.; Fusco, D.; Calandrini, E.; Bargagli, A.M. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Access to Healthcare Services amongst Patients with Multiple Sclerosis in the Lazio Region, Italy. Eur. J. Neurol. 2021, 28, 3403–3410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolksdorf, K.; Loenenbach, A.; Buda, S. Dritte Aktualisierung Der “Retrospektiven Phaseneinteilung Der COVID-19-Pandemie in Deutschland”. Epidemiol. Bull. 2022, 38, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herz, A. Soziale Kontakte Und Corona. Universität Hildesheim. Institut Für Sozial- Und Organisationspädagogik. Available online: https://www.uni-hildesheim.de/fb1/institute/institut-fuer-sozial-und-organisationspaedagogik/forschung/laufende-projekte/soziale-kontakte-corona/ (accessed on 9 December 2024).

- Mangiapane, S.; Kretschmann, J.; Czihal, T.; Von Stillfried, D. Veränderung Der Vertragsärztlichen Leistungsinanspruchnahme Während Der COVID-Krise. Tabellarischer Trendreport Bis Zum 1. Halbjahr 2022. Available online: https://www.zi.de/fileadmin/Downloads/Service/Publikationen/Trendreport_7_Leistungsinanspruchnahme_COVID_2022-12-08.pdf (accessed on 6 November 2024).

- Inojosa, H.; Schriefer, D.; Atta, Y.; Dillenseger, A.; Proschmann, U.; Schleußner, K.; Woopen, C.; Ziemssen, T.; Akgün, K. Insights from Real-World Practice: The Dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 Infections and Vaccinations in a Large German Multiple Sclerosis Cohort. Vaccines 2024, 12, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voigt, I.; Inojosa, H.; Dillenseger, A.; Haase, R.; Akgün, K.; Ziemssen, T. Digital Twins for Multiple Sclerosis. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 669811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krett, J.D.; Salter, A.; Newsome, S.D. Era of COVID-19 in Multiple Sclerosis Care. Neurol. Clin. 2024, 42, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, V.; Roos, I.; Monif, M.; Malpas, C.B.; Malpas, C.; Roberts, S.; Roberts, S.; Marriott, M.; Marriott, M.; Buzzard, K.; et al. Impact of Telehealth on Health Care in a Multiple Sclerosis Outpatient Clinic during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2022, 63, 103913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donzé, C.; Massot, C.; Kwiatkowski, A.; Guenot, M.; Hautecoeur, P. CONFISEP: Impact of the Covid-19 Pandemic Lockdown on Patients with Multiple Sclerosis in the North of France. Rev. Neurol. 2022, 178, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moumdjian, L.; Smedal, T.; Arntzen, E.C.; van der Linden, M.L.; Learmonth, Y.; Pedullà, L.; Tacchino, A.; Novotna, K.; Kalron, A.; Yazgan, Y.Z.; et al. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Physical Activity and Associated Technology Use in Persons with Multiple Sclerosis: An International RIMS-SIG Mobility Survey Study. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2022, 103, 2009–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonsdottir, J.; Santoyo-Medina, C.; Kahraman, T.; Kalron, A.; Rasova, K.; Moumdjian, L.; Coote, S.; Tacchino, A.; Grange, E.; Smedal, T.; et al. Changes in Physiotherapy Services and Use of Technology for People with Multiple Sclerosis during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2023, 71, 104520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahraman, T.; Rasova, K.; Jonsdottir, J.; Medina, C.S.; Kos, D.; Coote, S.; Tacchino, A.; Smedal, T.; Arntzen, E.C.; Quinn, G.; et al. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Physical Therapy Practice for People with Multiple Sclerosis: A Multicenter Survey Study of the RIMS Network. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2022, 62, 103799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, B.; Fong, K.N.K.; Meena, S.K.; Prasad, P.; Tong, R.K.Y. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic Lockdown on Occupational Therapy Practice and Use of Telerehabilitation—A Cross Sectional Study. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2021, 25, 3614–3622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goverover, Y.; Chen, M.H.; Botticello, A.; Voelbel, G.T.; Kim, G.; DeLuca, J.; Genova, H.M. Relationships between Changes in Daily Occupations and Health-Related Quality of Life in Persons with Multiple Sclerosis during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2022, 57, 103339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddi, S.; Giné-Vázquez, I.; Bailon, R.; Matcham, F.; Lamers, F.; Kontaxis, S.; Laporta, E.; Garcia, E.; Arranz, B.; Dalla Costa, G.; et al. Biopsychosocial Response to the COVID-19 Lockdown in People with Major Depressive Disorder and Multiple Sclerosis. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 7163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Tella, S.; Pagliari, C.; Blasi, V.; Mendozzi, L.; Rovaris, M.; Baglio, F. Integrated Telerehabilitation Approach in Multiple Sclerosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Telemed. Telecare 2020, 26, 385–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matysiak, M.; Siger, M.; Walczak, A.; Ciach, A.; Jonakowski, M.; Stasiołek, M. The Influence of COVID-19 Pandemic Lockdown on the Physical Activity of People with Multiple Sclerosis. The Role of Online Training. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2022, 63, 103843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altieri, M.; Capuano, R.; Bisecco, A.; D’Ambrosio, A.; Buonanno, D.; Tedeschi, G.; Santangelo, G.; Gallo, A. The Psychological Impact of Covid-19 Pandemic on People with Multiple Sclerosis: A Meta-Analysis. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2022, 61, 103774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarghami, A.; Hussain, M.A.; Campbell, J.A.; Ezegbe, C.; van der Mei, I.; Taylor, B.V.; Claflin, S.B. Psychological Impacts of COVID-19 Pandemic on Individuals Living with Multiple Sclerosis: A Rapid Systematic Review. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2022, 59, 103562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dillenseger, A.; Weidemann, M.L.; Trentzsch, K.; Inojosa, H.; Haase, R.; Schriefer, D.; Voigt, I.; Scholz, M.; Akgün, K.; Ziemssen, T. Digital Biomarkers in Multiple Sclerosis. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Participants 1st Survey (T1) | Participants 2nd Survey (T2) | Participants 3rd Survey (T3) | Participants 4th Survey (T4) | Complete Cases T1 to T4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n/nall | 750/946 | 441/946 | 411/946 | 422/946 | 240/946 |

| Response rate; % | 79.3 | 46.6 | 43.4 | 44.6 | 25.3 |

| Age; years, mean (SD) | 47.00 (13.05) | 49.01 (13.71) | 49.58 (13.32) | 49.53 (13.18) | 51.43 (13.42) |

| Range | 19–85 | 19–85 | 19–85 | 19–85 | 19–85 |

| Female; % | 74.4 | 77.3 | 76.4 | 76.5 | 79.6 |

| Place of Residence; % | |||||

| urban District | 44.7 | 44.7 | 43.8 | 43.4 | 41.3 |

| rural District | 55.3 | 55.3 | 56.2 | 56.6 | 58.8 |

| EDSS; median (IQR) | 2.5 (1.5–4.5) | 3.0 (1.5–5.0) | 3.0 (2.0–5.0) | 3.0 (1.5–5.0) | 3.0 (2.0–5.5) |

| Disease duration; years, median (IQR) | 10 (5–16) | 10 (5–16) | 11 (5–17) | 10 (5–16) | 12 (5–17.75) |

| Current immunotherapy; % | 76.1 | 72.1 | 72.0 | 72.2 | 69.6 |

| MS subtypes; % | |||||

| RRMS | 81.5 | 79.4 | 79.6 | 80.1 | 80.4 |

| SPMS | 8.8 | 10.4 | 10.5 | 10.0 | 11.3 |

| PPMS | 8.9 | 9.3 | 9.0 | 9.5 | 7.9 |

| CIS | 0.8 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| Variable | Visits Neurologist Item No. 1b | Visits Physiotherapist Item No. 1c | Online Sports Item No. 15 | Telemedicine Preference Item No. 13 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Age | ||||||||

| young (18–34) | 1 | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | 1 | |

| middle-aged (35–65) | 1.67 | 0.82–3.38 | 1.47 | 0.98–2.20 | 3.28 * | 2.23–4.83 | 1.13 | 0.72–1.75 |

| old (>65) | 3.37 * | 1.31–8.65 | 1.15 | 0.58–2.28 | 7.21 * | 2.74–18.96 | 0.87 | 0.40–1.90 |

| Disability (EDSS-Score) | ||||||||

| low (0–3.5) | 1 | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | 1 | |

| middle (4–6) | 1.05 | 0.53–2.10 | 1.23 | 0.80–1.88 | 1.95 * | 1.18–3.32 | 0.76 | 0.45–1.29 |

| high (6.5–9) | 1.45 | 0.67–3.18 | 1.49 | 0.90–2.47 | 5.62 * | 2.22–14.27 | 1.66 | 0.95–2.87 |

| Gender | ||||||||

| male | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | |

| female | 0.85 | 0.49–1.48 | 1.56 * | 1.06–2.30 | 0.65 | 0.42–1.01 | 0.80 | 0.53–1.20 |

| Residence | ||||||||

| urban districts | 1 | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | 1 | - |

| rural districts | 1.42 | 0.85–2.36 | 0.82 | 0.59–1.14 | 1.76 * | 1.23–2.50 | 0.53 * | 0.36–0.76 |

| Immune therapy | ||||||||

| none | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | |

| yes | 0.48 * | 0.28–0.82 | 0.80 | 0.55–1.17 | 0.72 | 0.46–1.13 | 0.80 | 0.50–1.15 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stölzer-Hutsch, H.; Schriefer, D.; Kugler, J.; Ziemssen, T. Patient Perspectives on Healthcare Utilization During the COVID-19 Pandemic in People with Multiple Sclerosis—A Longitudinal Analysis. Healthcare 2025, 13, 646. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13060646

Stölzer-Hutsch H, Schriefer D, Kugler J, Ziemssen T. Patient Perspectives on Healthcare Utilization During the COVID-19 Pandemic in People with Multiple Sclerosis—A Longitudinal Analysis. Healthcare. 2025; 13(6):646. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13060646

Chicago/Turabian StyleStölzer-Hutsch, Heidi, Dirk Schriefer, Joachim Kugler, and Tjalf Ziemssen. 2025. "Patient Perspectives on Healthcare Utilization During the COVID-19 Pandemic in People with Multiple Sclerosis—A Longitudinal Analysis" Healthcare 13, no. 6: 646. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13060646

APA StyleStölzer-Hutsch, H., Schriefer, D., Kugler, J., & Ziemssen, T. (2025). Patient Perspectives on Healthcare Utilization During the COVID-19 Pandemic in People with Multiple Sclerosis—A Longitudinal Analysis. Healthcare, 13(6), 646. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13060646