Indigenous Epistemological Frameworks and Evidence-Informed Approaches to Consciousness and Body Representations in Osteopathic Care: A Call for Academic Engagement

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Results

3.1. Body Representations in Manual Therapy

3.1.1. Integrating Physical and Non-Physical Dimensions into Body Representations

3.1.2. Western Biomedical Construction of Mind–Body Duality

3.1.3. Indigenous Healing Traditions: A Lived Bodily Experience Beyond Intellectual Processes

3.1.4. Reintegrating Indigenous Perspectives: The (R)evolution of Osteopathy Toward a Holistic Understanding of Body and Health

3.2. Insights from the Neuroscience of the Self: Integrating Non-Physical Body Dimensions and Cross-Cultural Influences in Osteopathic Care

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Degenhardt, B.; van Dun, P.L.S.; Jacobson, E.; Fritz, S.; Mettler, P.; Kettner, N.; Franklin, G.; Hensel, K.; Lesondak, D.; Consorti, G.; et al. Profession-based manual therapy nomenclature: Exploring history, limitations, and opportunities. J. Man. Manip. Ther. 2024, 32, 96–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, J.K.; Young, K.J. Vitalism in contemporary chiropractic: A help or a hinderance? Chiropr. Man. Ther. 2020, 28, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Draper-Rodi, J.; Newell, D.; Barbe, M.F.; Bialosky, J. Integrated manual therapies: IASP taskforce viewpoint. Pain Rep. 2024, 9, e1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coulter, I.; Snider, P.; Neil, A. Vitalism—A Worldview revisited: A critique of vitalism and its implications for Integrative Medicine. Integr. Med. 2019, 18, 60–73. [Google Scholar]

- Saad, M.; de Medeiros, R.; Mosini, A.C. Are We Ready for a True Biopsychosocial-Spiritual Model? The Many Meanings of “Spiritual”. Medicines 2017, 4, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, R.L. A landscape of consciousness: Toward a taxonomy of explanations and implications. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2024, 190, 28–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zegarra-Parodi, R.; D’Alessandro, G.; Baroni, F.; Swidrovich, J.; Mehl-Madrona, L.; Gordon, T.; Ciullo, L.; Castel, E.; Lunghi, C. Epistemological Flexibility in Person-Centered Care: The Cynefin Framework for (Re)Integrating Indigenous Body Representations in Manual Therapy. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osteopathic International Alliance Website. The OIA Global Report: Review of Osteopathic Medicine and Osteopathy 2020. Available online: https://oialliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/OIA_Report_2020_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- Zegarra-Parodi, R.; Draper-Rodi, J.; Haxton, J.; Cerritelli, F. The Native American Heritage of the Body-Mind-Spirit Paradigm in Osteopathic Principles and Practices. Int. J. Osteopath. Med. 2019, 33–34, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rountree, J.; Smith, A. Strength-based well-being indicators for Indigenous children and families: A literature review of Indigenous communities’ identified well-being indicators. Am. Indian Alsk. Nativ. Ment. Health Res. 2016, 23, 206–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mühlenpfordt, I.; Blakeslee, S.B.; Everding, J.; Cramer, H.; Seifert, G.; Stritter, W. Touching body, soul, and spirit? Understanding external applications from integrative medicine: A mixed methods systematic review. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 960960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, O.P.; MacMillan, A. What’s wrong with osteopathy? Int. J. Osteopath. Med. 2023, 48, 100659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, O.P.; Martini, C. Pseudoscience: A skeleton in osteopathy’s closet? Int. J. Osteopath. Med. 2024, 52, 100716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zegarra-Parodi, R.; Baroni, F.; Lunghi, C.; Dupuis, D. Historical Osteopathic Principles and Practices in Contemporary Care: An Anthropological Perspective to Foster Evidence-Informed and Culturally Sensitive Patient-Centered Care: A Commentary. Healthcare 2023, 11, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyreman, S. An anthropo-ecological narrative. In Textbook of Osteopathic Medicine; Mayer, J., Standen, C., Eds.; Elsevier: Berlin, Germany, 2018; pp. 159–165. [Google Scholar]

- Mehl-Madrona, L.; Conte, J.A.; Mainguy, B. Indigenous roots of osteopathy. AlterNative 2023, 19, 923–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berterö, C. Guidelines for Writing a Commentary. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2016, 11, 31390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jodelet, D. Les Représentations Sociales, 7th ed.; Presses Universitaires de France: Paris, France, 2003; pp. 45–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, Y. A New Perspective on Human Rights in the Use of Physical Restraint on Psychiatric Patients-Based on Merleau-Ponty’s Phenomenology of the Body. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyselo, M. The body social: An enactive approach to the self. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masi, M. An evidence-based critical review of the mind-brain identity theory. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1150605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinman, A.; Eisenberg, L.; Good, B. Culture, illness, and care: Clinical lessons from anthropologic and cross-cultural research. Ann. Intern. Med. 1978, 88, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorian, L.; Garfinkel, P.E. Culture and body image in Western society. Eat. Weight Disord. 2002, 7, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Rosa, W. Exploring the Global Applicability of Holistic Nursing. J. Holist. Nurs. 2017, 35, 7–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahnisch, F.W.; Verhoef, M. The flexner report of 1910 and its impact on complementary and alternative medicine and psychiatry in north america in the 20th century. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2012, 2012, 647896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheper-Hughes, N.; Lock, M.M. The Mindful Body: A Prolegomenon to Future Work in Medical Anthropology. Med. Anthropol. Q. 1987, 1, 6–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Breton, D. L’adieu au Corps; Editions Métaillé: Paris, France, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Engel, G.L. The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science 1977, 196, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO Website. Indigenous Peoples. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/indigenous-peoples (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Nixon, S.A. The coin model of privilege and critical allyship: Implications for health. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmermann, C.; Roseman, L.; Williams, L.; Erritzoe, D.; Martial, C.; Cassol, H.; Laureys, S.; Nutt, D.; Carhart-Harris, R. DMT Models the Near-Death Experience. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frecska, E.; Luna, L.E. Neuro-ontological interpretation of spiritual experiences. Neuropsychopharmacol. Hung. 2006, 8, 143–153. [Google Scholar]

- van Elk, M.; Aleman, A. Brain mechanisms in religion and spirituality: An integrative predictive processing framework. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2017, 73, 359–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, F.J.; D’Alonzo, G.E., Jr.; Glover, J.C.; Korr, I.M.; Osborn, G.G.; Patterson, M.M.; Seffinger, M.A.; Taylor, T.E.; Willard, F. Proposed tenets of osteopathic medicine and principles for patient care. J. Am. Osteopath. Assoc. 2002, 102, 63–65. [Google Scholar]

- Groenevelt, I.; Slatman, J. On the Affectivity of Touch: Enacting Bodies in Dutch Osteopathy. Med. Anthr. 2024, 43, 641–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struthers, R.; Eschiti, V.S.; Patchell, B. Traditional indigenous healing: Part I. Complement. Ther. Nurs. Midwifery 2004, 10, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tozzi, P. Does fascia hold memories? J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2014, 18, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liem, T.; Lunghi, C. Reconceptualizing Principles and Models in Osteopathic Care: A Clinical Application of the Integral Theory. Altern. Ther. Health Med. 2023, 29, 192–200. [Google Scholar]

- Lunghi, C.; Consorti, G.; Tramontano, M.; Esteves, J.E.; Cerritelli, F. Perspectives on tissue adaptation related to allostatic load: Scoping review and integrative hypothesis with a focus on osteopathic palpation. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2020, 24, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gélinas, C.; Bouchard, Y. An Epistemological Frameworkfor Indigenous Knowledge. Rev. Humanid. Valpso. 2015, 4, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerritelli, F.; Esteves, J.E. An Enactive–Ecological Model to Guide Patient-Centered Osteopathic Care. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Testa, M.; Rossettini, G. Enhance placebo, avoid nocebo: How contextual factors affect physiotherapy outcomes. Man. Ther. 2016, 24, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moerman, D.E. Meaning, Medicine, and the Placebo Effect; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002; Volume 28, p. 25. [Google Scholar]

- Baroni, F.; Ruffini, N.; D’Alessandro, G.; Consorti, G.; Lunghi, C. The role of touch in osteopathic practice: A narrative review and integrative hypothesis. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2021, 42, 101277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.A.; Cheong, J.H.; Jolly, E.; Elhence, H.; Wager, T.D.; Chang, L.J. Socially transmitted placebo effects. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2019, 3, 1295–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuscano, S.C.; Haxton, J.; Ciardo, A.; Ciullo, L.; Zegarra-Parodi, R. The Revisions of the First Autobiography of AT Still, the Founder of Osteopathy, as a Step towards Integration in the American Healthcare System: A Comparative and Historiographic Review. Healthcare 2024, 12, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrigoni, A.; Rossettini, G.; Palese, A.; Thacker, M.; Esteves, J.E. Exploring the role of therapeutic alliance and biobehavioural synchrony in musculoskeletal care: Insights from a qualitative study. Musculoskelet. Sci. Pract. 2024, 73, 103164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) Website. Introduction to Neural Basis of Mind-Body Pain Therapies Video. Available online: https://www.nccih.nih.gov/training/videolectures/11/1 (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Ninot, G.; Descamps, É.; Achalid, G.; Poisbeau, P.; Falissard, B. Cadre standardisé d’évaluation des interventions non médicamenteuses: Intérêts pour la masso-kinésithérapie. Kinesitherap 2024, 24, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerritelli, F.; Chiacchiaretta, P.; Gambi, F.; Perrucci, M.G.; Barassi, G.; Visciano, C.; Bellomo, R.G.; Saggini, R.; Ferretti, A. Effect of manual approaches with osteopathic modality on brain correlates of interoception: An fMRI study. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 3214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerritelli, F.; Chiacchiaretta, P.; Gambi, F.; Ferretti, A. Effect of Continuous Touch on Brain Functional Connectivity Is Modified by the Operator’s Tactile Attention. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, D. Reflecting on new models for osteopathy: It’s time for change. Int. J. Osteopath. Med. 2018, 31, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahlgren, E.; Nima, A.A.; Archer, T.; Garcia, D. Person-centered osteopathic practice: Patients’ personality (body, mind, and soul) and health (ill-being and well-being). PeerJ 2015, 3, e1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, R.T.H.; Sing, C.Y.; Wong, V.P.Y. Addressing holistic health and work empowerment through a body-mind-spirit intervention program among helping professionals in continuous education: A pilot study. Soc. Work Health Care 2016, 55, 779–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zegarra-Parodi, R.; Esteves, J.E.; Lunghi, C.; Baroni, F.; Draper-Rodi, J.; Cerritelli, F. The legacy and implications of the body-mind-spirit osteopathic tenet: A discussion paper evaluating its clinical relevance in contemporary osteopathic care. Int. J. Osteopath. Med. 2021, 41, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunghi, C.; Baroni, F. Cynefin Framework for Evidence-Informed Clinical Reasoning and Decision-Making. J. Am. Osteopath. Assoc. 2019, 119, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Level | Indigenous Narratives and Body Representations | Western Biomedical- Focused Perspectives |

|---|---|---|

| Personal Level | Emphasis on subjective experience, self-awareness, and personal growth | Focus on individual biology and physiology (e.g., genetic makeup, physical health) |

| Explores questions of identity, personal history, emotions, values, and purpose | Investigates the brain-body connection, mental health, and individual behavior | |

| Importance of emotions and internal states in shaping one’s interaction with the world | Psychological and neurological factors are viewed as separate from spiritual or emotional aspects | |

| Collective Level | Shared cultural values, roles, and group identity are central | Focus on social biology, social behaviors, and collective systems (e.g., group dynamics, norms) |

| Interactions within communities shape identity and the experience of owning a body | Emphasis on societal structures and cultural influences on individual behavior | |

| Highlights collective rituals, traditions, and intergenerational knowledge | Less emphasis on ritualistic or spiritual practices; more focus on social norms and group behaviors | |

| Transpersonal Level | Connection to spiritual, cosmic, or transcendent dimensions of existence | Typically, minimal focus on transcendent or spiritual aspects of the body |

| Interconnectedness with all living beings, the environment, and the universe | Focus on the material world, often ignoring spiritual/existential dimensions | |

| Exploration of universal principles, collective unconscious, and spiritual experiences | Biological determinism and empirical science often exclude spiritual/existential perspectives |

| Key Concepts of the Scientific Method Applied to Healthcare | |

|---|---|

| Intellectual Humility | Recognizing and integrating diverse worldviews to enhance understanding and collaboration |

| Science as a Bridge | Utilizing scientific methods to connect known and unknown perspectives effectively |

| Epistemological Flexibility | Acknowledging diverse worldviews and selecting the most suitable epistemological framework to support patients’ sense-making |

| Theories on Consciousness [6] | |

| Nonmaterialistic Worldviews | Materialistic Worldviews |

| Brain as a receptor of consciousness | Brain as an emitter of consciousness |

| Body as a vehicle for experience (“human being”) | Body as a mechanical system (“human doing”) |

| The Influence of the Flexner Report on Osteopathic Education [46] | |

| Nonmaterialistic Worldviews | Materialistic Worldviews |

| Non-physical components of the body (emotions, existential dimension) considered pseudoscience | Only physical components of the body considered worthy of investigation |

| Therapeutic framework built around the patient experience (illness model) | Therapeutic framework built around observed biological components (disease model) |

| Incorporating Indigenous epistemological frameworks in osteopathic care (the body–mind–spirit tenet) | Therapeutic framework built around observed biological components (disease model) |

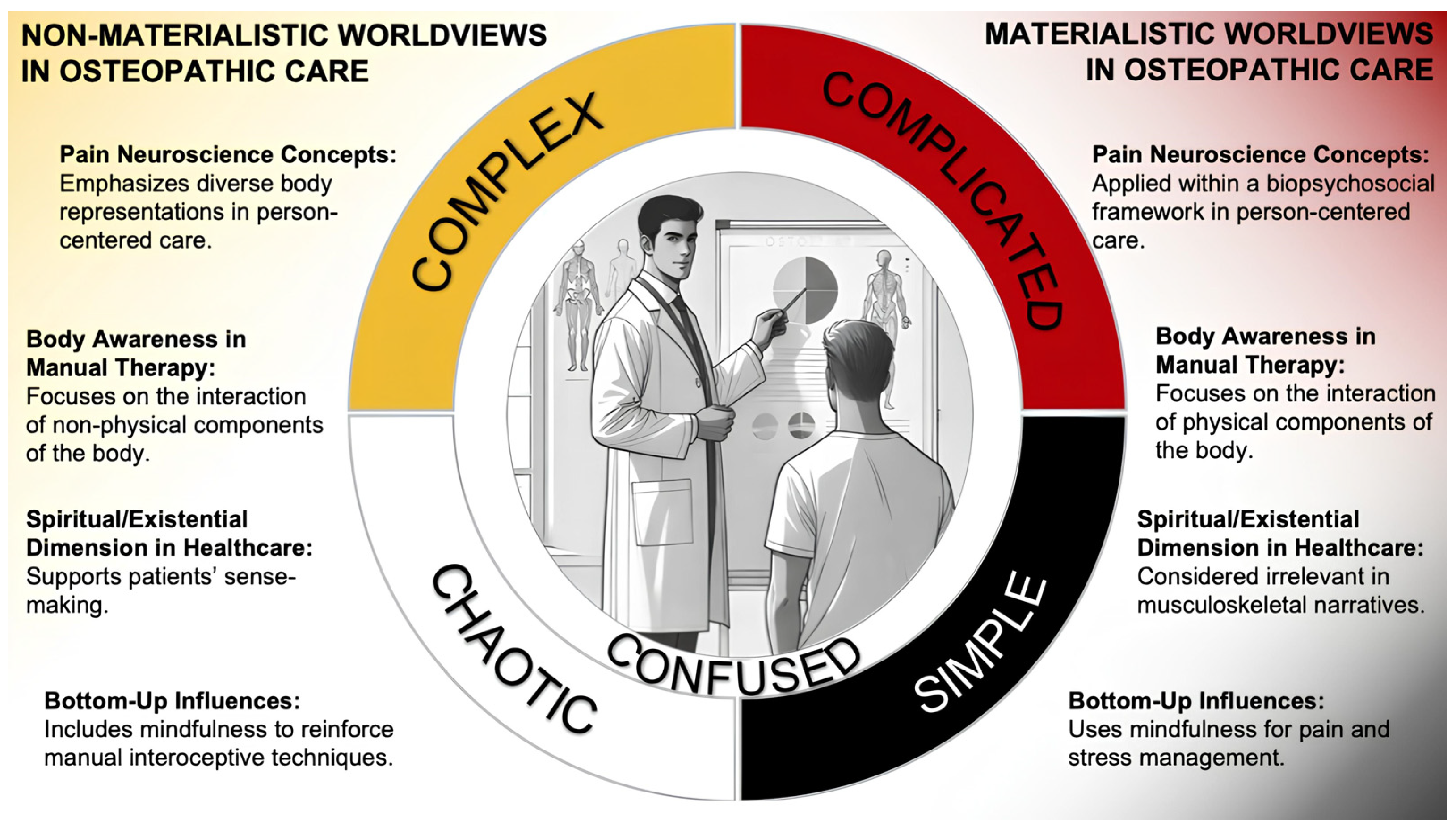

| The Cynefin Framework to Guide Culturally Sensitive and Person-Centered Osteopathic Care [7,56] | |

| Nonmaterialistic Worldviews | Materialistic Worldviews |

| Pain neuroscience concepts consider the diversity of body representations in person-centered care | Pain neuroscience concepts applied within a biopsychosocial framework in person-centered care |

| Body awareness in manual therapy focuses on the interaction of non-physical components of the body | Body awareness in manual therapy focuses on the interaction of physical components of the body |

| The spiritual/existential dimension in healthcare might be included in the narrative to support patients’ sense-making | The spiritual/existential dimension in healthcare is considered not relevant for a musculoskeletal-focused narrative |

| Bottom-up influences might include mindfulness approaches to reinforce manual interoceptive techniques | Bottom-up influences might include mindfulness approaches for pain management and stress reduction |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zegarra-Parodi, R.; Loum, T.; D’Alessandro, G.; Baroni, F.; Zweedijk, R.; Schillinger, S.; Conte, J.; Mehl-Madrona, L.; Lunghi, C. Indigenous Epistemological Frameworks and Evidence-Informed Approaches to Consciousness and Body Representations in Osteopathic Care: A Call for Academic Engagement. Healthcare 2025, 13, 586. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13060586

Zegarra-Parodi R, Loum T, D’Alessandro G, Baroni F, Zweedijk R, Schillinger S, Conte J, Mehl-Madrona L, Lunghi C. Indigenous Epistemological Frameworks and Evidence-Informed Approaches to Consciousness and Body Representations in Osteopathic Care: A Call for Academic Engagement. Healthcare. 2025; 13(6):586. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13060586

Chicago/Turabian StyleZegarra-Parodi, Rafael, Thioro Loum, Giandomenico D’Alessandro, Francesca Baroni, René Zweedijk, Stéphan Schillinger, Josie Conte, Lewis Mehl-Madrona, and Christian Lunghi. 2025. "Indigenous Epistemological Frameworks and Evidence-Informed Approaches to Consciousness and Body Representations in Osteopathic Care: A Call for Academic Engagement" Healthcare 13, no. 6: 586. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13060586

APA StyleZegarra-Parodi, R., Loum, T., D’Alessandro, G., Baroni, F., Zweedijk, R., Schillinger, S., Conte, J., Mehl-Madrona, L., & Lunghi, C. (2025). Indigenous Epistemological Frameworks and Evidence-Informed Approaches to Consciousness and Body Representations in Osteopathic Care: A Call for Academic Engagement. Healthcare, 13(6), 586. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13060586