Shared Decision-Making on Life-Sustaining Treatment: A Survey of Current Barriers in Practice Among Clinicians Across China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Survey Instrument

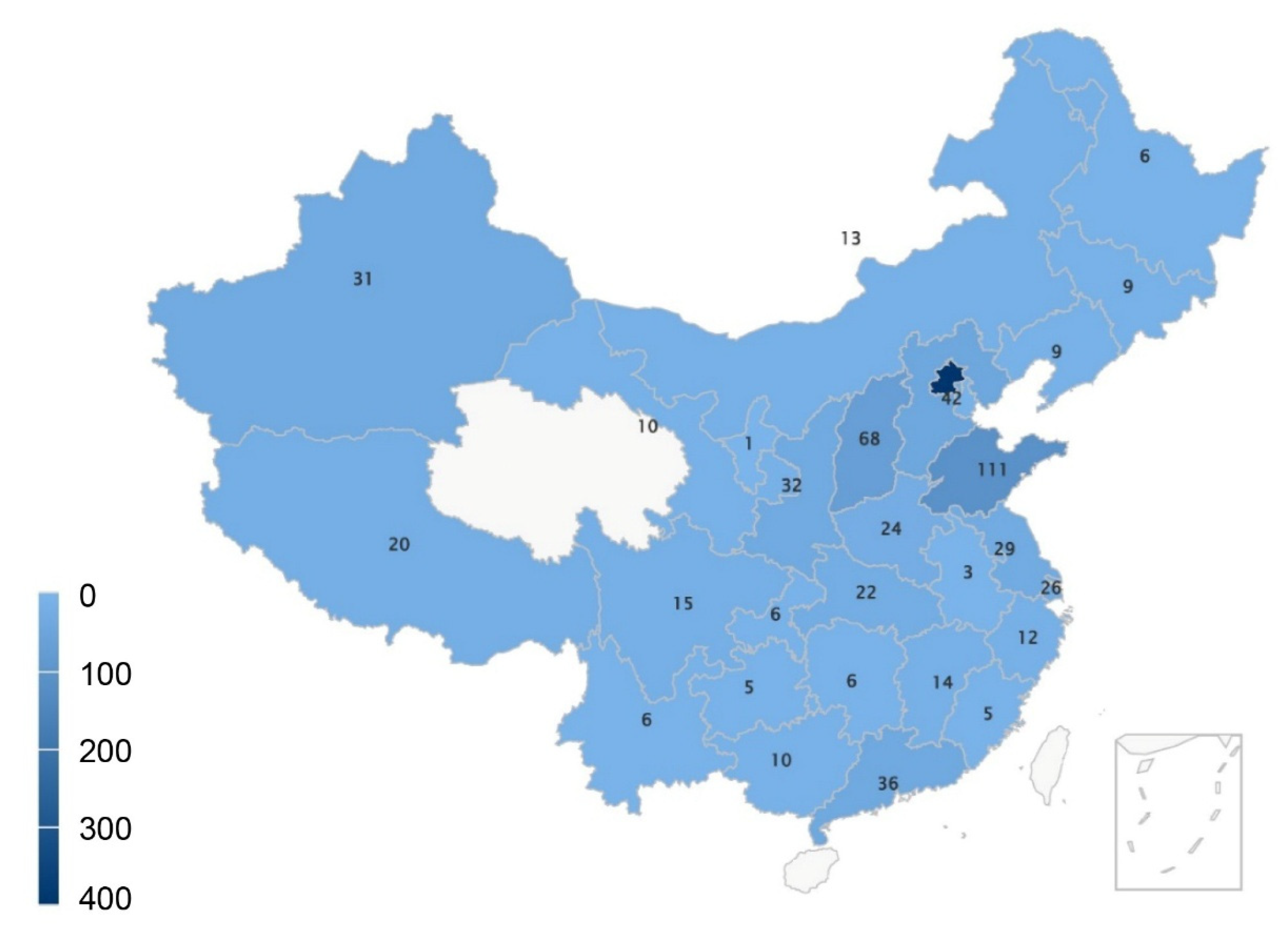

2.2. Study Setting and Population

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.4. Ethical Approval

3. Results

3.1. Participant Demographic Characteristics

3.2. Main Barriers of Decision-Making Conversation

3.3. Decision-Making Model and Patient Values Expression

3.4. Decisional Abilities of Patients/Families

3.5. Features of Communication Patterns

3.5.1. Prognosis Evaluation and Disclosure

3.5.2. Objectiveness of Risk–Benefit Interpretations

3.5.3. Time and Opportunity of the Conversation

3.6. Exploratory Factor Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Physician Population

4.2. Patient Value Inadequately Expressed

4.3. Gap Between Patient/Family Comprehension and Disease Complexity

4.4. Physician Efforts and Discrepancies

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AD | advanced directives |

| CFI | comparative fit index |

| CPR | cardiopulmonary resuscitation |

| GOC | goals-of-care |

| ICU | intensive care unit |

| IHCA | in-hospital cardiac arrest |

| IQR | interquartile range |

| LST | life-sustaining treatment |

| NFI | normed fit index |

| RMSEA | root mean square error of approximation |

| ROSC | return of spontaneous circulation |

| SDM | shared decision-making |

| SEM | structural equation model |

| SRMR | SRMR, standardized root mean square residual |

| TLI | Tucker–Lewis index |

| WLSMV | weighted least squares means and variance |

References

- Légaré, F.; O’Connor, A.C.; Graham, I.; Saucier, D.; Côté, L.; Cauchon, M.; Paré, L. Supporting patients facing difficult health care decisions: Use of the Ottawa Decision Support Framework. Can. Fam. Physician 2006, 52, 476–477. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Miller, M.E.; Siegler, M.; Angelos, P. Ethical Issues in Surgical Innovation. World J. Surg. 2014, 38, 1638–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Probst, M.A.; Kanzaria, H.K.; Frosch, D.L.; Hess, E.P.; Winkel, G.; Ngai, K.M.; Richardson, L.D. Perceived Appropriateness of Shared Decision-making in the Emergency Department: A Survey Study. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2016, 23, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, M.; Georgiou, A.; Dahm, M.R.; Li, J.; Thomas, J. Shared Decision-Making in Emergency Departments: Context Sensitivity Through Divergent Discourses. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2019, 265, 128–133. [Google Scholar]

- Hogan, T.M.; Richmond, N.L.; Carpenter, C.R.; Biese, K.; Hwang, U.; Shah, M.N.; Escobedo, M.; Berman, A.; Broder, J.S.; Platts-Mills, T.F. Shared Decision Making to Improve the Emergency Care of Older Adults: A Research Agenda. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2016, 23, 1386–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probst, M.A.; Kanzaria, H.K.; Schoenfeld, E.M.; Menchine, M.D.; Breslin, M.; Walsh, C.; Melnick, E.R.; Hess, E.P. Shared Decisionmaking in the Emergency Department: A Guiding Framework for Clinicians. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2017, 70, 688–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenfeld, E.M.; Probst, M.A.; Quigley, D.D.; St Marie, P.; Nayyar, N.; Sabbagh, S.H.; Beckford, T.; Kanzaria, H.K. Does Shared Decision Making Actually Occur in the Emergency Department- Looking at It from the Patients’ Perspective. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2019, 26, 1369–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouchi, K.; George, N.; Schuur, J.D.; Aaronson, E.L.; Lindvall, C.; Bernstein, E.; Sudore, R.L.; Schonberg, M.A.; Block, S.D.; Tulsky, J.A. Goals-of-Care Conversations for Older Adults With Serious Illness in the Emergency Department: Challenges and Opportunities. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2019, 74, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanzaria, H.K.; Chen, E.H. Shared Decision Making for the Emergency Provider: Engaging Patients When Seconds Count. MedEdPORTAL 2020, 16, 10936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babitsch, B.; Braun, T.; Borde, T.; David, M. Doctor’s perception of doctor-patient relationships in emergency departments: What roles do gender and ethnicity play? BMC Health Serv. Res. 2008, 8, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spatz, E.S.; Krumholz, H.M.; Moulton, B.W. The New Era of Informed Consent: Getting to a Reasonable-Patient Standard Through Shared Decision Making. JAMA 2016, 315, 2063–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stretti, F.; Klinzing, S.; Ehlers, U.; Steiger, P.; Schuepbach, R.; Krones, T.; Brandi, G. Low Level of Vegetative State After Traumatic Brain Injury in a Swiss Academic Hospital. Anesth. Analg. 2018, 127, 698–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoenfeld, E.M.; Kanzaria, H.K.; Quigley, D.D.; Marie, P.S.; Nayyar, N.; Sabbagh, S.H.; Gress, K.L.; Probst, M.A. Patient Preferences Regarding Shared Decision Making in the Emergency Department: Findings From a Multisite Survey. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2018, 25, 1118–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flynn, D.; Knoedler, M.A.; Hess, E.P.; Murad, M.H.; Erwin, P.J.; Montori, V.M.; Thomson, R.G. Engaging patients in health care decisions in the emergency department through shared decision-making: A systematic review. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2012, 19, 959–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noseworthy, P.A.; Brito, J.P.; Kunneman, M.; Hargraves, I.G.; Zeballos-Palacios, C.; Montori, V.M.; Ting, H.H. Shared decision-making in atrial fibrillation: Navigating complex issues in partnership with the patient. J. Interv. Card. Electrophysiol. 2019, 56, 159–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sypher, B.; Hall, R.T.; Rosencrance, G. Autonomy, informed consent and advance directives: A study of physician attitudes. West Va. Med. J. 2005, 101, 131–133. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce, C.R.; Bibler, T.; Childress, A.M.; Stephens, A.L.; Pena, A.M.; Allen, N.G. Navigating Ethical Conflicts Between Advance Directives and Surrogate Decision-Makers’ Interpretations of Patient Wishes. Chest 2016, 149, 562–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The State Council of the People’s Republic of China. Civil Code of the People’s Republic of China. Available online: http://english.www.gov.cn/archive/lawsregulations/202012/31/content_WS5fedad98c6d0f72576943005.html (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- Bernacki, R.E.; Block, S.D.; American College of Physicians High Value Care Task Force. Communication about serious illness care goals: A review and synthesis of best practices. JAMA Intern. Med. 2014, 174, 1994–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouchi, K.; Knabben, V.; Rivera-Reyes, L.; Ganta, N.; Gelfman, L.P.; Sudore, R.; Hwang, U. Preparing Older Adults with Serious Illness to Formulate Their Goals for Medical Care in the Emergency Department. J. Palliat. Med. 2017, 20, 404–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, N.; Bernacki, R.E. Goals of Care Conversations in Serious Illness: A Practical Guide. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 104, 375–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gips, A.; Daubman, B.-R.; Petrillo, L.A.; Bowman, J.; Ouchi, K.; Traeger, L.; Jackson, V.; Grudzen, C.; Ritchie, C.S.; Aaronson, E.L. Palliative care in the emergency department: A qualitative study exploring barriers, facilitators, desired clinician qualities, and future directions. Palliat. Support. Care 2022, 20, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, N.R.; Kryworuchko, J.; Hunold, K.M.; Ouchi, K.; Berman, A.; Wright, R.; Grudzen, C.R.; Kovalerchik, O.; LeFebvre, E.M.; Lindor, R.A.; et al. Shared Decision Making to Support the Provision of Palliative and End-of-Life Care in the Emergency Department: A Consensus Statement and Research Agenda. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2016, 23, 1394–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlin, A. Goals of Care and End of Life in the ICU. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2017, 97, 1275–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, N.; Detering, K.M.; Low, T.; Nolte, L.; Fraser, S.; Sellars, M. Doctors’ perspectives on adhering to advance care directives when making medical decisions for patients: An Australian interview study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e032638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanzaria, H.K.; Brook, R.H.; Probst, M.A.; Harris, D.; Berry, S.H.; Hoffman, J.R. Emergency physician perceptions of shared decision-making. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2015, 22, 399–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baxter, R.; Pusa, S.; Andersson, S.; Fromme, E.K.; Paladino, J.; Sandgren, A. Core elements of serious illness conversations: An integrative systematic review. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2023, 14, e2268–e2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatcher, L. A Step-by-Step Approach to Using the SAS® System for Factor Analysis and Structural Equation Modeling; SAS Institute, Inc.: Cary, NC, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Sprung, C.L.; Truog, R.D.; Curtis, J.R.; Joynt, G.M.; Baras, M.; Michalsen, A.; Briegel, J.; Kesecioglu, J.; Efferen, L.; De Robertis, E.; et al. Seeking worldwide professional consensus on the principles of end-of-life care for the critically Ill. The Consensus for Worldwide End-of-Life Practice for Patients in Intensive Care Units (WELPICUS) Study. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2014, 190, 855–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, M.B.; Rao, N. Disclosure and Truth in Physician–Patient Communication An Exploratory Analysis in Argentina, Brazil, India and the United States. J. Creat. Commun. 2016, 2, 279–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probst, M.A.; Noseworthy, P.A.; Brito, J.P.; Hess, E.P. Shared Decision-Making as the Future of Emergency Cardiology. Can. J. Cardiol. 2018, 34, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegler, M. The progression of medicine. From physician paternalism to patient autonomy to bureaucratic parsimony. Arch. Intern. Med. 1985, 145, 713–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teno, J.M.; Gruneir, A.; Schwartz, Z.; Nanda, A.; Wetle, T. Association between advance directives and quality of end-of-life care: A national study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2007, 55, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graber, A.; April, C.; April, M.D. Proxy Consent by a Physician When a Patient’s Capacity Is Equivocal: Respecting a Patient’s Autonomy by Overriding the Patient’s Ostensible Treatment Preferences. J. Clin. Ethics 2018, 29, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouchi, K.; Lawton, A.J.; Bowman, J.; Bernacki, R.; George, N. Managing Code Status Conversations for Seriously Ill Older Adults in Respiratory Failure. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2020, 76, 751–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anselm, A.H.; Palda, V.; Guest, C.B.; McLean, R.F.; Vachon, M.L.; Kelner, M.; Lam-McCulloch, J. Barriers to communication regarding end-of-life care: Perspectives of care providers. J. Crit. Care 2005, 20, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ip, M.; Gilligan, T.; Koenig, B.; Raffin, T.A. Ethical decision-making in critical care in Hong Kong. Crit. Care Med. 1998, 26, 447–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schillinger, D.; Duran, N.D.; McNamara, D.S.; Crossley, S.A.; Balyan, R.; Karter, A.J. Precision communication: Physicians’ linguistic adaptation to patients’ health literacy. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabj2836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandolin, N.S.; Huang, W.; Beckett, L.; Wintemute, G. Perspectives of emergency department attendees on outcomes of resuscitation efforts: Origins and impact on cardiopulmonary resuscitation preference. Emerg. Med. J. 2020, 37, 611–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beil, M.; van Heerden, P.V.; Joynt, G.M.; Lapinsky, S.; Flaatten, H.; Guidet, B.; de Lange, D.; Leaver, S.; Jung, C.; Forte, D.N.; et al. Limiting life-sustaining treatment for very old ICU patients: Cultural challenges and diverse practices. Ann. Intensive Care 2023, 13, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouchi, K.; Jambaulikar, G.D.; Hohmann, S.; George, N.R.; Aaronson, E.L.; Sudore, R.; Schonberg, M.A.; Tulsky, J.A.; Schuur, J.D.; Pallin, D.J. Prognosis After Emergency Department Intubation to Inform Shared Decision-Making. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2018, 66, 1377–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouchi, K.; Bello, J.L.; Moseley, E.; Lindvall, C. Long-Term Prognosis of Older Adults Who Survive Emergency Mechanical Ventilation. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2020, 60, 1019–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, M.; Doherty, C.P.; Naci, L. Using Neuroimaging to Detect Covert Awareness and Determine Prognosis of Comatose Patients: Informing Surrogate Decision Makers of Individual Patient Results. Semin. Neurol. 2018, 38, 555–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myers, J.; Cosby, R.; Gzik, D.; Harle, I.; Harrold, D.; Incardona, N.; Walton, T. Provider Tools for Advance Care Planning and Goals of Care Discussions: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care. 2018, 35, 1123–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oczkowski, S.J.W.; Chung, H.-O.; Hanvey, L.; Mbuagbaw, L.; You, J.J. Communication tools for end-of-life decision-making in the intensive care unit: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Care 2016, 20, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chary, A.; Joshi, C.; Castilla-Ojo, N.; Santangelo, I.; Ouchi, K.; Naik, A.D.; Carpenter, C.R.; Liu, S.W.; Kennedy, M.; Joshi, C.S.; et al. Emergency Clinicians’ Perceptions of Communication Tools to Establish the Mental Baseline of Older Adults: A Qualitative Study. Cureus 2021, 13, e20616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.C.; Han, M.; Ko, G.-J.; Yang, J.W.; Kwon, S.H.; Chung, S.; Hong, Y.A.; Hyun, Y.Y.; Cho, J.-H.; Yoo, K.D.; et al. Effect of shared decision-making education on physicians’ perceptions and practices of end-of-life care in Korea. Kidney Res. Clin. Pract. 2022, 41, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J. Literature review: Decision-making regarding slow resuscitation. J. Clin. Nurs. 2007, 16, 1989–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piscitello, G.M.; Kapania, E.M.; Kanelidis, A.; Siegler, M.; Parker, W.F. The Use of Slow Codes and Medically Futile Codes in Practice. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2021, 62, 326–335.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | N of Physicians (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex, female | 481 (57.7) |

| Education background, doctor’s degree in medicine | 557 (66.8) |

| Years of medical practice | |

| <10 years | 453 (54.3) |

| 10–20 years | 259 (31.1) |

| >20 years | 122 (14.6) |

| Title | |

| Senior | 228 (27.3) |

| Median | 325 (39.0) |

| Junior | 281 (33.7) |

| Hospital level, Tertiary hospital | 696 (83.5) |

| Specialty | |

| Emergency medicine | 264 (31.7) |

| Internal medicine | 198 (23.7) |

| Surgery | 101 (12.1) |

| Intensive medicine | 90 (10.8) |

| Cardiology | 77 (9.2) |

| Work time per week | |

| 40~50 h | 336 (40.3) |

| 50~60 h | 286 (34.3) |

| >60 h | 212 (25.4) |

| Performing CPR | |

| Often | 364 (43.6) |

| Sometimes | 272 (32.6) |

| Occasionally | 184 (22.1) |

| Never | 14 (1.7) |

| Performing CPR during past month | |

| ≥5 times | 96 (11.5) |

| 2~4 times | 204 (24.5) |

| ≤1 time | 534 (24.8) |

| Previous doctor–patient communication training | 622 (74.6) |

| Main Barrier to Doctor–Patient Conversations | N of Physician (%) |

|---|---|

| Patient/family member over-expectations of disease prognosis | 778 (93.3) |

| Patient/family member lack of medical knowledge | 716 (85.9) |

| Patient/family member’s negative emotional status | 574 (68.8) |

| Neglected patient autonomy | 429 (51.4) |

| Lack of time due to physician workload | 359 (43.0) |

| Lack of communication skills of healthcare professionals | 310 (37.2) |

| Insufficient physician ability to cope with difficult situations | 203 (24.3) |

| Decision Category | Excellent | Good | Moderate | Insufficient | Extremely Insufficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decisional ability, n (%) | 73 (8.8) | 303 (36.3) | 362 (43.4) | 86 (10.3%) | 10 (1.2%) |

| Understanding of the necessity and urgency of LST, n (%) | 82 (9.8) | 279 (33.5) | 366 (43.9%) | 91 (10.9%) | 16 (1.9%) |

| Comprehension of risk and prognosis of patients receive LST, n (%) | 45 (5.4) | 154 (18.5) | 428 (51.3%) | 173 (20.7%) | 34 (4.1%) |

| Usually | Sometimes | Occasionally | Rarely | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concordant with physician judgment, n (%) | 577 (69.2) | 197 (23.6) | 52 (6.2) | 8 (1.0) |

| Stick to decisions, n (%) | 399 (47.8) | 266 (31.9%) | 158 (18.9%) | 11 (1.3%) |

| Decision Category | Usually | Sometimes | Occasionally | Never |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Review the patient’s comorbidities and daily living status, n (%) | 558 (66.9) | 185 (22.2) | 74 (8.9) | 17 (2.0) |

| Explain the main issue and general prognosis, n (%) | 758 (90.9) | 57 (5.8) | 16 (1.9) | 3 (0.4) |

| Used tools (e.g., web videos, pictures), n (%) | 88 (10.6) | 196 (23.5) | 246 (29.5) | 304 (36.5) |

| Mentioned alternatives to LST, n (%) | 580 (69.5) | 163 (19.5) | 74 (8.9) | 17 (2.0) |

| Mentioned the consequences of forgoing LST, n (%) | 640 (76.7) | 139 (16.7) | 38 (4.6) | 17 (2.0) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, S.; Ma, Q. Shared Decision-Making on Life-Sustaining Treatment: A Survey of Current Barriers in Practice Among Clinicians Across China. Healthcare 2025, 13, 547. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13050547

Liang Y, Zhang H, Li S, Ma Q. Shared Decision-Making on Life-Sustaining Treatment: A Survey of Current Barriers in Practice Among Clinicians Across China. Healthcare. 2025; 13(5):547. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13050547

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiang, Yang, Hua Zhang, Shu Li, and Qingbian Ma. 2025. "Shared Decision-Making on Life-Sustaining Treatment: A Survey of Current Barriers in Practice Among Clinicians Across China" Healthcare 13, no. 5: 547. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13050547

APA StyleLiang, Y., Zhang, H., Li, S., & Ma, Q. (2025). Shared Decision-Making on Life-Sustaining Treatment: A Survey of Current Barriers in Practice Among Clinicians Across China. Healthcare, 13(5), 547. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13050547