Meshing Anxiety, Depression, Quality of Life, and Functionality in Chronic Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

2.2. Data Extraction

3. Results

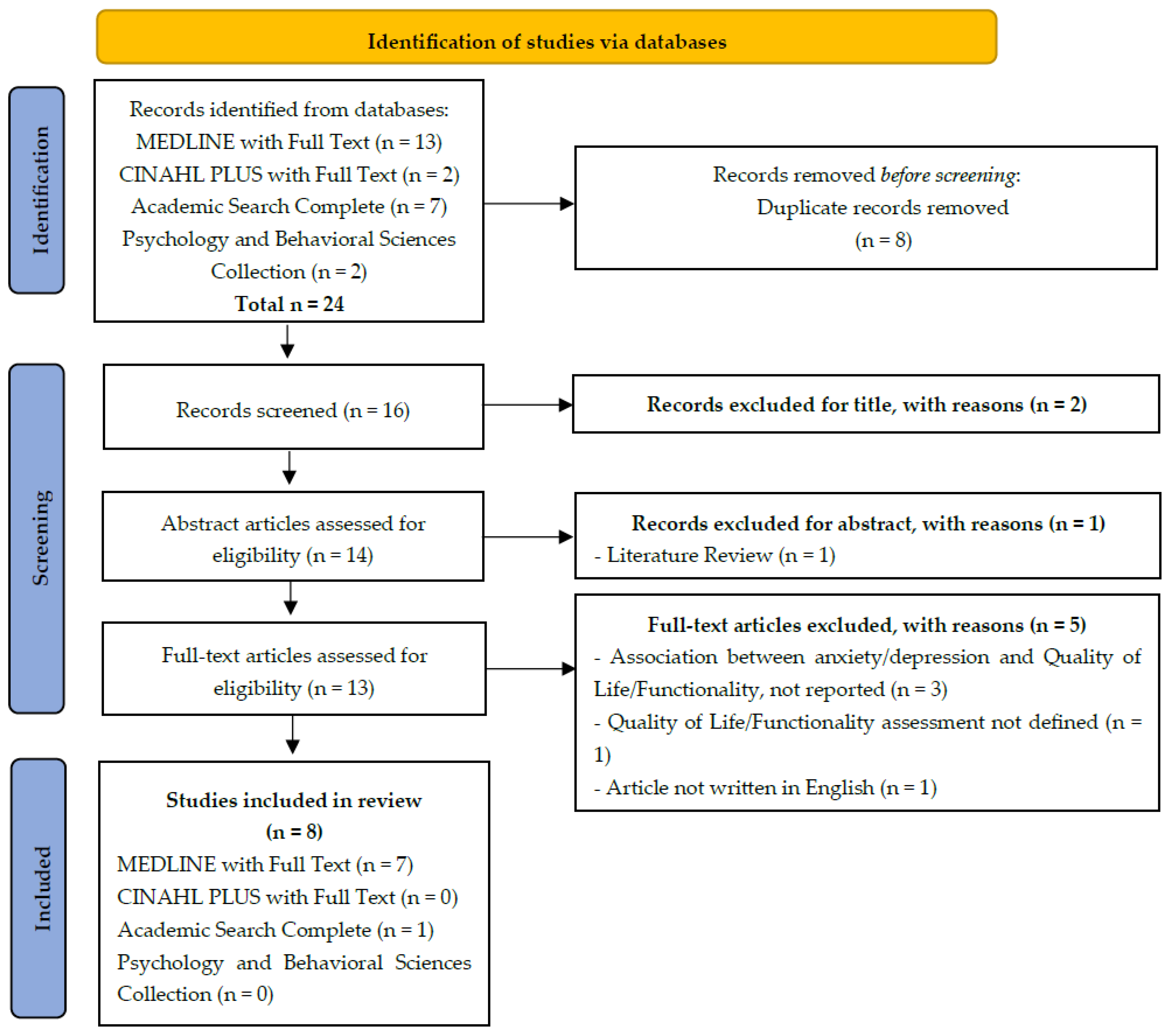

3.1. Literature Search

3.2. Study Characteristics

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wu, Y.; Wang, L.; Tao, M.; Cao, H.; Yuan, H.; Ye, M.; Chen, X.; Wang, K.; Zhu, C. Changing Trends in the Global Burden of Mental Disorders from 1990 to 2019 and Predicted Levels in 25 Years. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 2023, 32, e63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IHME. Global Burden of Disease with Major Processing by OurWorldinData. Anxiety Disorders. 2022. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/mental-health (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Tiller, J.W.G. Depression and Anxiety. Med. J. Aust. 2012, 1, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization International Classification of Diseases (11th Revision). Available online: https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/classification-of-diseases (accessed on 3 May 2023).

- König, H.; König, H.H.; Konnopka, A. The Excess Costs of Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Epidemiol Psychiatr. Sci. 2019, 29, e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konnopka, A.; König, H. Economic Burden of Anxiety Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Pharmacoeconomics 2020, 38, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, Y.; Gong, Y.; Tong, X.; Sun, H.; Cong, Y.; Dong, X.; Wang, Y.; Xu, X.; Yin, X.; Deng, J.; et al. Depression and the Risk of Coronary Heart Disease: A Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. BMC Psychiatry 2014, 14, 12888–13014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tully, P.J.; Harrison, N.J.; Cheung, P.; Cosh, S. Anxiety and Cardiovascular Disease Risk: A Review. Curr Cardiol Rep 2016, 18, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. DSM-5-TR; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrinho, C. Relação Entre Ansiedade, Depressão, Qualidade de Vida e Satisfação Profissional Nos Funcionários Não-Docentes Da Universidade Da Beira Interior. Master’s Thesis, University of Beira Interior, Covilhã, Portugal, 4 July 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Freidl, M.; Wegerer, M.; Litvan, Z.; König, D.; Alexandrowicz, R.W.; Portela-Millinger, F.; Gruber, M. Determinants of Quality of Life Improvements in Anxiety and Depressive Disorders—A Longitudinal Study of Inpatient Psychotherapy. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 937194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. How to Use the ICF―A Practical Manual for Using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF); WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fillenbaum, G.G. The Wellbeing of the Elderly: Approaches to Multidimensional Assessment; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1984; Volume 85, pp. 1–99. [Google Scholar]

- McKnight, P.E.; Monfort, S.S.; Kashdan, T.B.; Blalock, D.V.; Calton, J.M. Anxiety Symptoms and Functional Impairment: A Systematic Review of the Correlation between the Two Measures. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2016, 45, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer-Helmich, L.; Haro, J.M.; Jönsson, B.; Melac, A.T.; Di Nicola, S.; Chollet, J.; Milea, D.; Rive, B.; Saragoussi, D. Functional Impairment in Patients with Major Depressive Disorder: The 2-Year PERFORM Study. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2018, 14, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKnight, P.E.; Kashdan, T.B. The Importance of Functional Impairment to Mental Health Outcomes: A Case for Reassessing Our Goals in Depression Treatment Research. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2009, 29, 243–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Group Whoqol. Development of the WHOQOL: Rationale and Current Status. Int. J. Ment. Health 1994, 23, 24–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canavarro, M.C.; Pereira, M.; Moreira, H.; Paredes, T. Qualidade de Vida e Saíde: Aplicações WHOQOL. Qualidade de Vida Na Perspectiva Da Organização Mundial de Saúde (OMS). Alicerces 2010, 5, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hohls, J.K.; König, H.H.; Quirke, E.; Hajek, A. Anxiety, Depression and Quality of Life—A Systematic Review of Evidence from Longitudinal Observational Studies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Loux, T.; Huang, X.; Feng, X. The Relationship between Chronic Diseases and Mental Health: A Cross-Sectional Study. Ment. Health Prev. 2023, 32, 200307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shantz, E.; Elliott, S.J. Chronic Disease. In International Encyclopedia of Human Geography, 2nd ed.; Audrey, K., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 187–191. [Google Scholar]

- IHME. Global Burden of Disease with Major Processing by OurWorldinData. Cancers. 2022. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/burden-of-disease (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Al Qadire, M.; ALHosni, F.; Al-Daken, L.; Aljezawi, M.; Al Omari, O.; Khalaf, A. Quality of Life and Its Predictors among Patients with Selected Chronic Diseases. Nurs. Forum 2023, 2023, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadakkiniath, I.J. Prevalence and Correlates of Stress, Anxiety, and Depression in Patients with Chronic Diseases: A Cross-Sectional Study. Middle East Curr. Psychiatry 2023, 30, 66. [Google Scholar]

- Verhaak, P.F.M.; Heijmans, M.J.W.M.; Peters, L.; Rijken, M. Chronic Disease and Mental Disorder. Soc. Sci. Med. 2005, 60, 789–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choo, C.C.; Chew, P.K.H.; Ho, C.S.; Ho, R.C. Quality of Life in Patients with a Major Mental Disorder in Singapore. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. BMJ 2009, 339, 332–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI). Checklist for Analytical Cross Sectional Studies; JBI: Adelaide, SA, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nogueira, I.C.; Araújo, A.S.; Morano, M.T.; Cavalcante, A.G.; de Bruin, P.F.; Paddison, J.S.; da Silva, G.P.; Barros Pereira, E.D. Assessment of Fatigue Using the Identity-Consequence Fatigue Scale in Patients with Lung Cancer. J. Bras. De Pneumol. 2017, 43, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiesa Fuxench, Z.C.; Block, J.K.; Boguniewicz, M.; Boyle, J.; Fonacier, L.; Gelfand, J.M.; Grayson, M.H.; Margolis, D.J.; Mitchell, L.; Silverberg, J.I.; et al. Atopic Dermatitis in America Study: A Cross-Sectional Study Examining the Prevalence and Disease Burden of Atopic Dermatitis in the US Adult Population. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2019, 139, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Amore, C.; O’Hoski, S.; Griffith, L.E.; Richardson, J.; Goldstein, R.S.; Beauchamp, M.K. Factors Associated with Participation in Life Situations in People with COPD. Chron. Respir. Dis. 2022, 19, 14799731221079305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colombino, I.C.F.; Sarri, A.J.; Castro, I.Q.; Paiva, C.E.; da Costa Vieira, R.A. Factors Associated with Return to Work in Breast Cancer Survivors Treated at the Public Cancer Hospital in Brazil. Support. Care Cancer 2020, 28, 4445–4458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aktar, B.; Balci, B.; Colakoglu, D. Physical Activity in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease: A Holistic Approach Based on the ICF Model. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2020, 198, 106132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bejer, A.; Ćwirlej-Sozańska, A.; Wiśniowska-Szurlej, A.; Wilmowska-Pietruszyńska, A.; Spalek, R.; de Sire, A.; Sozański, B. Psychometric Properties of the Polish Version of the 36-Item WHODAS 2.0 in Patients with Hip and Knee Osteoarthritis. Qual. Life Res. 2021, 30, 2415–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, C.L.; Udy, A.A.; Bailey, M.; Barrett, J.; Bellomo, R.; Bucknall, T.; Gabbe, B.J.; Higgins, A.M.; Iwashyna, T.J.; Hunt-Smith, J.; et al. The Impact of Disability in Survivors of Critical Illness. Intensive Care Med. 2017, 43, 992–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koirala, R.; Iyer Søegaard, E.G.; Kan, Z.; Ojha, S.P.; Hauff, E.; Thapa, S.B. Exploring Complex PTSD in Patients Visiting a Psychiatric Outpatient Clinic in Kathmandu, Nepal. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2021, 143, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Ozaki, F.; Rodrigo Valentin de Souza, Â.; umberto Castro Lima Filho, H.; Maria Cruz Santos, A.; Mota Lopes, J.; Guimarães Bastos, C.; Marcelino Siquara, G. Efeito Das Relações Familiares e Do Humor Na Qualidade de Vida de Pacientes Com Epilepsia. Rev. Neuropsicol. Latinoam. 2022, 4, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjelland, I.; Dahl, A.A.; Haug, T.; Neckelmann, D. The Validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale an Updated Literature Review. J. Psychosom. Res. 2002, 52, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altemus, M.; Sarvaiya, N.; Neill Epperson, C. Sex Differences in Anxiety and Depression Clinical Perspectives. Front. Neuroendocr. 2014, 35, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubecka, B.; Lubecki, M.; Kasperczyk, J.; Jo’sko-Ochojska, J.J.; Pudlo, R.; Rodero-Cosano, M.L.; Salinas-Perez, J.A.; Conejo-Cerón, S.; Bagheri, N.; Castelpietra, G. Risk Modifying Factors of Anxiety and Depressive Disorders, Using the Example of a Population Study in the Zywiec District. Public Health 2021, 18, 10248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, G.; Xie, F.; Li, S.; Ding, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, H. The Relationship between Perceived Social Support with Anxiety, Depression, and Insomnia among Chinese College Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Mediating Role of Self-Control. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 994376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy-Byrne, P.; Afari, N.; Ashton, S.; Fischer, M.; Goldberg, J.; Buchwald, D. Chronic Fatigue and Anxiety/Depression: A Twin Study. Br. J. Psychiatry 2002, 180, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Bobo, W.V.; Grossardt, B.R.; Virani, S.; St Sauver, J.L.; Boyd, C.M.; Rocca, W.A. Association of Depression and Anxiety with the Accumulation of Chronic Conditions. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, E229817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Guan, H.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Rui, M.; Ma, A. Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients with Different Diseases Measured With the EQ-5D-5L: A Systematic Review. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 675523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Code | Ref. | Quest * | Primary Disease | Anxiety/Depression Instrument | Quality of Life Instrument | Functionality Instrument | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | ||||||

| 3BR2017 | [29] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Lung cancer | HADS | SF-36 | 6MWD |

| 4US2019 | [30] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Atopic dermatitis | HADS | HRQoL; DLQI | - |

| 9CA2022 | [31] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | HADS | - | 6MWD; SPPB; LLDI |

| 10BR2020 | [32] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Breast cancer | HADS | EORTC QLQ- BR23 | SPADI |

| 11TR2020 | [33] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Parkinson’s disease | BDI; BAI | PDQ-8 | MDS-UPDRS; SWA; 6MWT; TUG; YAHR; FIS |

| 12PL2021 | [34] | Y | U | Y | Y | U | U | Y | Y | Hip and knee osteoarthritis | HADS | SF-36 2.0 | WHODAS 2.0 |

| 13AU2017 | [35] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Critical illness | HADS | EQ5D-5L | WHODAS 2.0 + 3.0 |

| 5NEP2021 | [36] | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Post-traumatic stress disorder | CIDI 2.1 | WHOQOL-BREF | - |

| % | 100 | 88.89 | 100 | 100 | 77.78 | 77.78 | 100 | 100 | |||||

| # | 9 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 7 | 7 | 9 | 9 | |||||

| Code | Ref. | Primary Disease | Anxiety and Depression Values by Groups | Quality of Life Values by Groups | Functionality Values by Groups |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3BR2017 | [29] | Lung cancer [LC] + Chronic heart disease [CHD] | Lung cancer: - HADS-A: 5 (3–8) - HADS-D: 4.5 (2.0–7.0) Values are expressed as median (interquartile range). - No results were presented for control group | Lung cancer: - SF-36 MCSb: 47.7 (13.3) - SF-36 PCSb: 45.6 (8.4) Values are expressed as mean (SD) - Fatigue experiences: r = −0.55; p < 0.01 - Fatigue impacts: r = −0.48; p ≤ 0.01 - No results were presented for control group | - Anxiety fatigue experiences: r = 0.43; p ≤ 0.01 - Depression fatigue experiences: r = 0.60; p ≤ 0.01 - Anxiety fatigue impacts: r = 0.62; p ≤ 0.01 - Depression fatigue impacts: r = 0.63; p ≤ 0.01 |

| 4US2019 | [30] | Atopic dermatitis [AD] | - HADS-A total score: 7.03 (4.80) - HADS-D total score: 5.83 (4.54) Values are expressed as mean (SD) - Clear or Mild AD HADS-A total score: 6.09 (4.22) - Moderate AD HADS-A total score: 8.22 (4.81) - Severe AD HADS-A total score: 10.45 (5.22) Values are expressed as mean (SD) - Clear or mild AD HADS-D total score: 4.86 (3.99) - Moderate AD HADS-D total score: 6.7 (4.33) - Severe AD HADS-D total score: 8.11 (3.84) Values are expressed as mean (SD) - HADS-A control group total score: 4.73 (3.98) - HADS-D control group total score: 3.62 (3.61) Values are expressed as mean (SD) | - DLQI total score: 4.71 (6.44) - Clear or mild AD DLQI total score: 2.04 (2.79) - Moderate AD DLQI total score: 5.87 (6.26) - Severe AD DLQI total score: 11.44 (8.48) - DLQI control group total score: 0.97 (2.12) Values are expressed as mean (SD) | Ø |

| 9CA2022 | [31] | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD] | - Every 1-point increase on the HADS was associated with a 0.27 decrease in the participation score - Every 1-point increase in the psychological distress outcome (HADS) resulted in a 0.15 decrease in participation frequency. - No control group | Ø | - One-m increase in 6MWT distance, participation frequency score increased by 0.03 points - One-m increase in 6MWT distance, participation frequency score increased by 0.04 points - No control group |

| 10BR2020 | [32] | Breast cancer | - HADS-A total: 9.84 (5.03) - HADS-D total: 7.68 (3.29) Values are expressed as mean (SD) HADS-A NRTW: 11.37 (4.91) - HADS-D NRTW: 8.70 (3.00) - HADS-A RTW: 8.69 (4.82) - HADS-D RTW: 6.91 (3.31) Values are expressed as mean (SD) - No control group | - Only presents results for each domain and not the total value of the instrument - No control group | - SPADI—incapacity total: 31.99 (26.12) - SPADI—pain total: 41.88 (31.55) - SPADI—incapacity NRTW: 42.53 (27.51) - SPADI—pain NRTW: 52.51 (32.86) - SPADI—incapacity RTW: 24.05 (22.03) - SPADI—pain RTW: 23.87 (28.14) Values are expressed as mean (SD) - No control group |

| 12PL2021 | [34] | Hip and knee osteoarthritis [HKOA] | - HADS-A: 7.09 (3.60) - HADS-D: 6.04 (4.04) Values are expressed as mean (SD) - No control group | - Only presents results for each domain and not the total value of the instrument - No control group | - WHODAS 2.0 total: 38.33 (17.28) Values are expressed as mean (SD) - Every 1-point increase in the HADS-A resulted in a 0.475 increase in WHODAS 2.0 total score - every 1-point increase in the HADS-D resulted in a 0.536 increase in WHODAS 2.0 total score |

| 13AU2017 | [35] | Critical illness | - No control group | None or mild disability: - EQ5D-5L utility score: 0.77 (0.26) Moderate or severe disability - EQ5D-5L utility score: 0.50 (0.26) Values are expressed as mean (SD) | None or mild disability: - HADS-A: 3.50 (3.10) - HADS-D: 2.90 (2.80) Moderate or severe disability - HADS-A: 7.30 (4.70) - HADS-D: 7.00 (4.00) Values are expressed as mean (SD) |

| 11TR2020 | [33] | Parkinson’s disease [PD] | - BAI sedentary PD: 9.28 (8.73) - BDI sedentary PD: 12.32 (9.41) - BAI non-sedentary PD: 7.60 (10.05) - BDI non-sedentary PD: 11.31 (6.66) Values are expressed as mean (SD) p-value not significant - No control group | - PDQ-8 sedentary PD: 20.50 (19.51) - PDQ-8 non-sedentary PD: 15.89 (14.97) Values are expressed as mean (SD) p-value not significant - No control group | - MDS-UPDRS p-value not significant - SWA WA- step width (cm) WA- step length (cm) p-value not significant for both - WA- walking speed (cm/s). Sedentary PD: 49.84 (17.57) - WA- Walking speed (cm/s). Non-sedentary PD: 62.20 (12.52) - 6MWT sedentary PD: 387.02 (85.16) - 6MWT non-sedentary PD: 445.78 (70.83) - TUG sedentary PD: 9.62 (2.76) - TUG non-sedentary PD: 7.78 (1.20) Values are expressed as mean (SD) - YAHR p-value not significant - FIS p-value not significant - No control group |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pedro Costa, A.; da Silva Brito, I.; Mestre, T.D.; Matos Pires, A.; José Lopes, M. Meshing Anxiety, Depression, Quality of Life, and Functionality in Chronic Disease. Healthcare 2025, 13, 539. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13050539

Pedro Costa A, da Silva Brito I, Mestre TD, Matos Pires A, José Lopes M. Meshing Anxiety, Depression, Quality of Life, and Functionality in Chronic Disease. Healthcare. 2025; 13(5):539. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13050539

Chicago/Turabian StylePedro Costa, Ana, Irma da Silva Brito, Teresa Dionísio Mestre, Ana Matos Pires, and Manuel José Lopes. 2025. "Meshing Anxiety, Depression, Quality of Life, and Functionality in Chronic Disease" Healthcare 13, no. 5: 539. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13050539

APA StylePedro Costa, A., da Silva Brito, I., Mestre, T. D., Matos Pires, A., & José Lopes, M. (2025). Meshing Anxiety, Depression, Quality of Life, and Functionality in Chronic Disease. Healthcare, 13(5), 539. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13050539