Transitional Care Interventions in Improving Patient and Caregiver Outcomes After Discharge: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

Aim

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

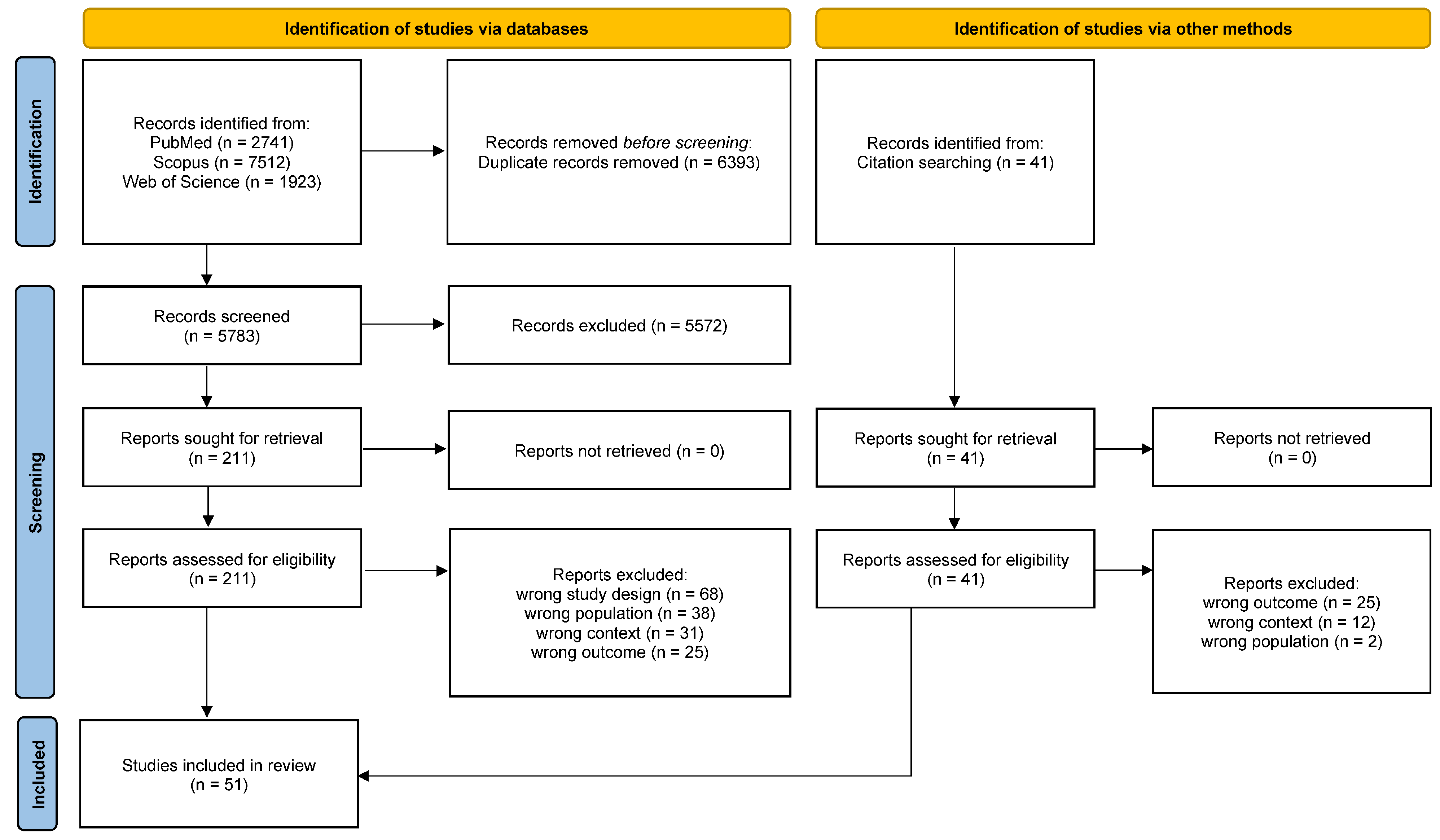

2.2. Screening and Selection Process

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Data Synthesis

2.5. Search Results

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Studies

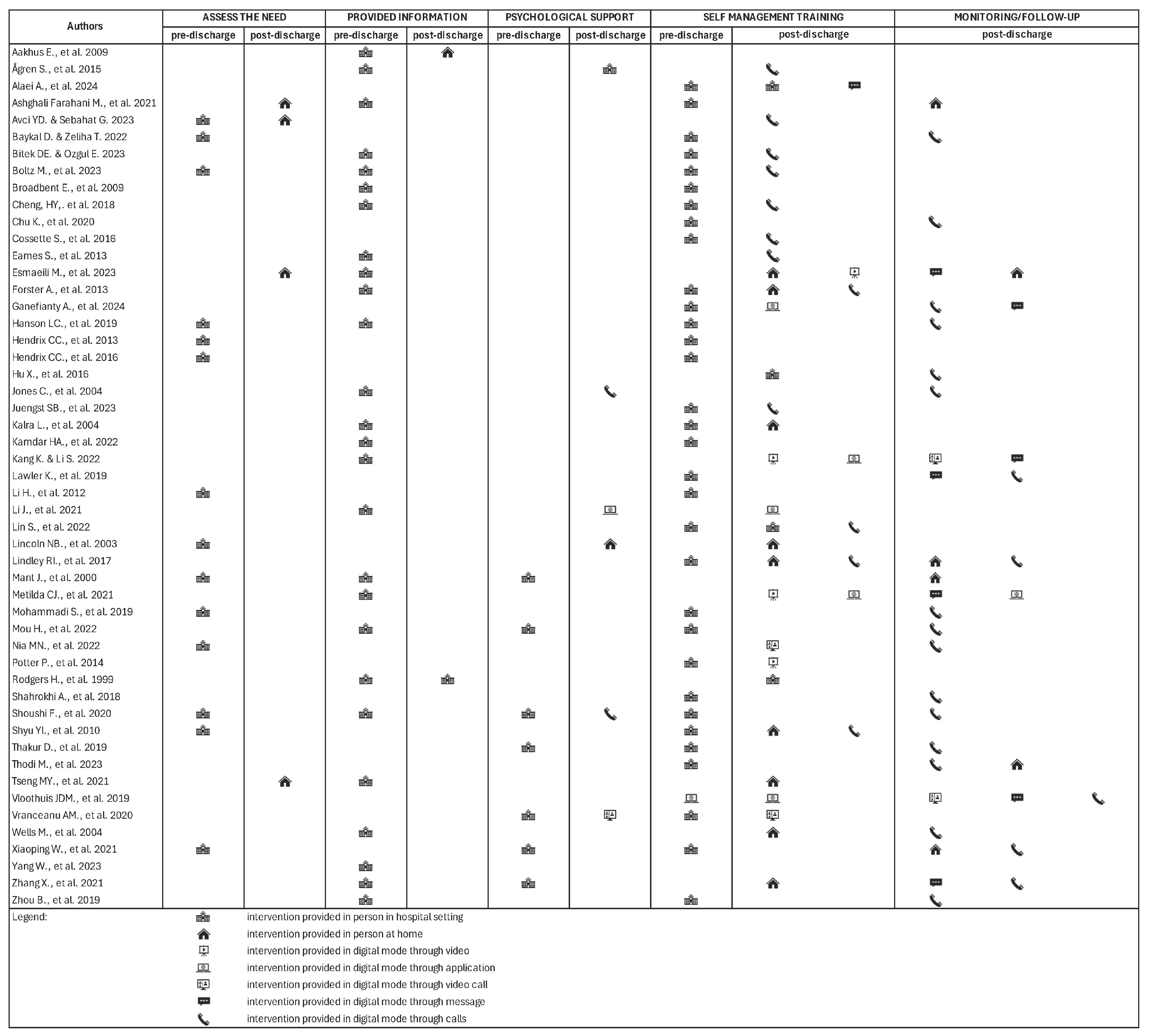

3.2. Transitional Care Interventions

3.2.1. Needs Assessment

3.2.2. Providing Information

3.2.3. Psychological Support

3.2.4. Self-Management Training

3.2.5. Monitoring and Follow-Up

3.3. Roles in Transitional Care Interventions

3.4. Outcomes of Transitional Care Interventions

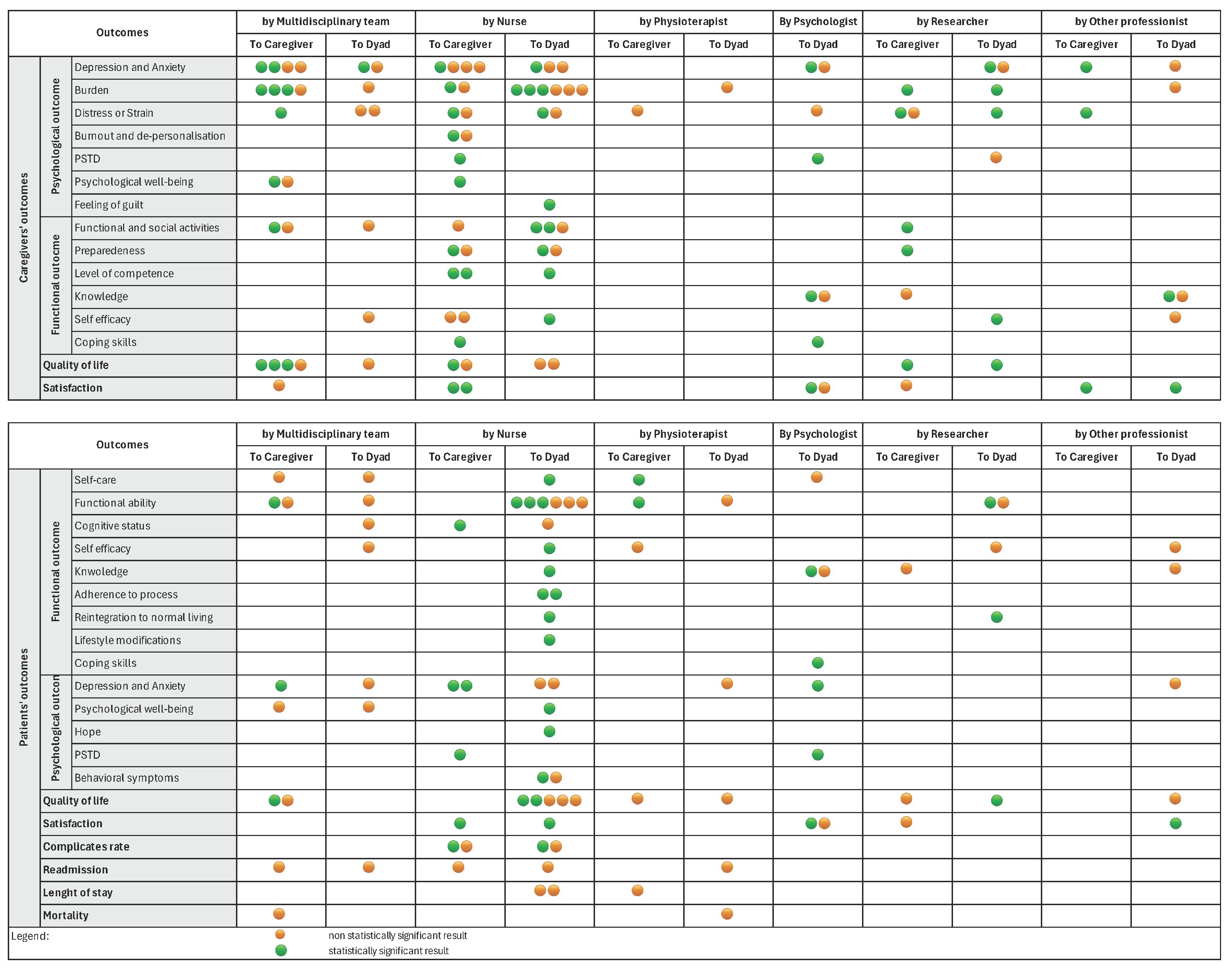

3.4.1. Caregivers’ Outcomes

3.4.2. Patients’ Outcomes

3.4.3. Follow-Up

4. Discussion

4.1. Transitional Care Interventions and the Caregivers’ Involvement

4.2. Outcomes of Transitional Care Interventions

5. Strengths and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Multimorbidity: Technical Series on Safer Primary Care; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Holland, D.E.; Harris, M.R. Discharge planning, transitional care, coordination of care, and continuity of care: Clarifying concepts and terms from the hospital perspective. Home Health Care Serv. Q. 2007, 26, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coleman, E.A.; Parry, C.; Chalmers, S.; Min, S.J. The Care Transitions Intervention: Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1822–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Earl, T.; Katapodis, N.; Schneiderman, S. Making Healthcare Safer III: A Critical Analysis of Existing and Emerging Patient Safety Practices; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD, USA, 2020; Report No.: 20-0029-EF. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Graham, C.L.; Ivey, S.L.; Neuhauser, L. From hospital to home: Assessing the transitional care needs of vulnerable seniors. Gerontologist 2009, 49, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, J.; Hutchinson, A.M.; Brown, R. Quality care outcomes following transitional care interventions for older people from hospital to home: A systematic review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, A.D.; Popalisky, J.; Simon, T.D. The effectiveness of family-centered transition processes from hospital settings to home: A review of the literature. Hosp. Pediatr. 2015, 5, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiaoping, W.; Yueying, G.; Jin, L.; Xiyan, T.; Qian, L.; Danping, G. Effects of care transitions intervention mode on the benefit-finding in caregivers for patients with acute cerebral infarction. Signa Vitae 2021, 17, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Xiao, L.D.; Chamberlain, D.; Ullah, S.; Wang, Y.; Shen, Y.; Chen, Z.; Wu, M. Nurse-led health coaching program to improve hospital-to-home transitional care for stroke survivors: A randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ. Couns. 2022, 105, 917–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avci, D.Y.; Gözüm, S. Effects of Transitional Care Model-Based Interventions for Stroke Patients and Caregivers on Caregivers’ Competence and Patient Outcomes: Randomized Controlled Trial. Comput. Inform. Nurs. 2023, 41, 805–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morkisch, N.; Upegui-Arango, L.D.; Cardona, M.I.; Van den Heuvel, D.; Rimmele, M.; Sieber, C.C.; Freiberger, E. Components of the transitional care model to reduce readmission in geriatric patients: A systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebzeit, D.; Rutkowski, R.; Arbaje, A.I.; Fields, B.; Werner, N.E. A scoping review of interventions for older adults transitioning from hospital to home. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2021, 69, 2950–2962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prvu Bettger, J.; Alexander, K.P.; Dolor, R.J.; Olson, D.M.; Kendrick, A.S.; Wing, L.; Duncan, P.W. Transitional care after hospitalization for acute stroke or myocardial infarction: A systematic review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2012, 157, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vedel, I.; Khanassov, V. Transitional care for patients with congestive heart failure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Fam. Med. 2015, 13, 562–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chartrand, J.; Shea, B.; Hutton, B.; Dingwall, O.; Kakkar, A.; Chartrand, M.; Poulin, A.; Backman, C. Patient- and family-centred care transition interventions for adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2023, 35, mzad102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saunders, S.; Killackey, T.; Kurahashi, A.; Walsh, C.; Wentlandt, K.; Lovrics, E.; Scott, M.; Mahtani, R.; Bernstein, M.; Howard, M.; et al. Palliative care transitions from acute care to community-based care: A systematic review. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2019, 58, 721–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.O.; Pearson, M.; Pfeiffer, K.; Crotty, M.; Lamb, S.E. Caregiver interventions for adults discharged from the hospital: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2019, 67, 1960–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyesanya, T.O.; Loflin, C.; Byom, L.; Harris, G.; Daly, K.; Rink, L.; Bettger, J.P. Transitions of care interventions to improve quality of life among patients hospitalized with acute conditions: A systematic literature review. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2021, 19, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dy, S.M.; Apostol, C.; Martinez, K.A.; Aslakson, R.A. Continuity, coordination, and transitions of care for patients with serious and advanced illness: A systematic review of interventions. J. Palliat. Med. 2013, 16, 436–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dijk, M.; Vreven, J.; Deschodt, M.; Verheyden, G.; Tournoy, J.; Flamaing, J. Can in-hospital or post-discharge caregiver involvement increase functional performance of older patients? A systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariza-Vega, P.; Ortiz-Piña, M.; Kristensen, M.T.; Castellote-Caballero, Y.; Jiménez-Moleón, J.J. High perceived caregiver burden for relatives of patients following hip fracture surgery. Disabil. Rehabil. 2019, 41, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitlin, L.N.; Wolff, J. Family involvement in care transitions of older adults: What do we know and where do we go from here? Annu. Rev. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2012, 31, 31–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirschman, K.B.; Shaid, E.; McCauley, K.; Pauly, M.V.; Naylor, M.D. Continuity of care: The transitional care model. Online J. Issues Nurs. 2015, 20, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nia, M.N.; Mohajer, S.; Bagheri, N.; Sarboozi-hoseinabadi, T. The effects of family-centered empowerment model on depression, anxiety, and stress of the family caregivers of patients with COVID-19: A randomized clinical trial. BMC Prim. Care 2022, 23, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendrix, C.C.; Landerman, R.; Abernethy, A.P. Effects of an individualized caregiver training intervention on self-efficacy of cancer caregivers. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2013, 35, 590–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrix, C.C.; Bailey, D.E.; Steinhauser, K.E.; Olsen, M.K.; Stechuchak, K.M.; Lowman, S.G.; Schwartz, A.J.; Riedel, R.F.; Keefe, F.J.; Porter, L.S.; et al. Effects of enhanced caregiver training program on cancer caregiver’s self-efficacy, preparedness, and psychological well-being. Support. Care Cancer 2016, 24, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, S.; Zabolypour, S.; Ghaffari, F.; Arazi, T. The effect of family-oriented discharge program on the level of preparedness for caregiving and stress experienced by the family of stroke survivors. Iran. Rehabil. J. 2019, 17, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Lin, J.L.; Gao, R.; Chen, N.; Huang, G.F.; Wang, L.; Gao, H.; Zhuo, H.Z.; Chen, L.Q.; Chen, X.H.; et al. Application of the hospital-family holistic care model in caregivers of patients with permanent enterostomy: A randomized controlled trial. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021, 77, 2033–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.; Skirrow, P.; Griffiths, R.D.; Humphris, G.; Ingleby, S.; Eddleston, J.; Waldmann, C.; Gager, M. Post-traumatic stress disorder-related symptoms in relatives of patients following intensive care. Intensive Care Med. 2004, 30, 456–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ågren, S.; Strömberg, A.; Jaarsma, T.; Luttik, M.L. Caregiving tasks and caregiver burden; effects of a psycho-educational intervention in partners of patients with post-operative heart failure. Heart Lung 2015, 44, 270–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadbent, E.; Ellis, C.J.; Thomas, J.; Gamble, G.; Petrie, K.J. Can an illness perception intervention reduce illness anxiety in spouses of myocardial infarction patients? A randomized controlled trial. J. Psychosom. Res. 2009, 67, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Powers, B.A.; Melnyk, B.M.; McCann, R.; Koulouglioti, C.; Anson, E.; Smith, J.A.; Xia, Y.; Glose, S.; Tu, X. Randomized controlled trial of CARE: An intervention to improve outcomes of hospitalized elders and family caregivers. Res. Nurs. Health 2012, 35, 533–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, B.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Li, X.; Anderson, C.S.; Xie, B.; Wang, N.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, X.; Bettger, J.P.; et al. Caregiver-delivered stroke rehabilitation in rural China: The RECOVER randomized controlled trial. Stroke 2019, 50, 1825–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Li, Q.P.; Yang, B.H. Participatory continuous nursing using the WeChat platform for patients with spinal cord injuries. J. Int. Med. Res. 2021, 49, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boltz, M.; Mogle, J.; Kuzmik, A.; Belue, R.; Leslie, D.; Galvin, J.E.; Resnick, B. Testing an intervention to improve posthospital outcomes in persons living with dementia and their family care partners. Innov. Aging 2023, 7, igad083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juengst, S.B.; Wright, B.; Driver, S.; Calhoun, S.; Muir, A.; Dart, G.; Goldin, Y.; Lengenfelder, J.; Bell, K. Multisite randomized feasibility study of problem-solving training for care partners of adults with traumatic brain injury during inpatient rehabilitation. NeuroRehabilitation 2023, 52, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamdar, H.A.; Gianchandani, S.; Strohm, T.; Yadav, K.; Chou, C.Z.; Reed, L.; Norton, K.; Hinduja, A. Collaborative integration of palliative care in critically ill stroke patients in the neurocritical care unit: A single center pilot study. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2022, 31, 106586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Dolansky, M.A.; Su, Y.; Hu, X.; Qu, M.; Zhou, L. Effect of a multidisciplinary supportive program for family caregivers of patients with heart failure on caregiver burden, quality of life, and depression: A randomized controlled study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2016, 62, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aakhus, E.; Engedal, K.; Aspelund, T.; Selbaek, G. Single session educational program for caregivers of psychogeriatric inpatients: Results from a randomized controlled pilot study. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2009, 24, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forster, A.; Dickerson, J.; Young, J.; Patel, A.; Kalra, L.; Nixon, J.; Smithard, D.; Knapp, M.; Holloway, I.; Anwar, S.; et al. A cluster randomized controlled trial and economic evaluation of a structured training program for caregivers of inpatients after stroke: The TRACS trial. Health Technol. Assess. 2013, 17, 1–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shyu, Y.I.L.; Kuo, L.M.; Chen, M.C.; Chen, S.T. A clinical trial of an individualized intervention program for family caregivers of older stroke victims in Taiwan. J. Clin. Nurs. 2010, 19, 1675–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mant, J.; Carter, J.; Wade, D.T.; Winner, S. Family support for stroke: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2020, 356, 808–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lincoln, N.B.; Francis, V.M.; Lilley, S.A.; Sharma, J.C.; Summerfield, M. Evaluation of a stroke family support organizer: A randomized controlled trial. Stroke 2003, 34, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanson, L.C.; Kistler, C.E.; Lavin, K.; Gabriel, S.L.; Ernecoff, N.C.; Lin, F.-C.; Sachs, G.A.; Mitchell, S.L. Triggered palliative care for late-stage dementia: A pilot randomized trial. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2019, 57, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoushi, F.; Janati, Y.; Mousavinasab, N.; Kamali, M.; Shafipour, V. The impact of family support program on depression, anxiety, stress, and satisfaction in the family members of open-heart surgery patients. J. Nurs. Midwifery Sci. 2020, 7, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baykal, D.; Tülek, Z. The effect of discharge training on quality of life, self-efficacy, and reintegration to normal living in stroke patients and their informal caregivers: A randomized controlled trial. Neurol. Asia 2022, 27, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashghali Farahani, M.; Najafi Ghezeljeh, T.; Haghani, S.; Alazmani-Noodeh, F. The effect of a supportive home care program on caregiver burden with stroke patients in Iran: An experimental study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, M.-Y.; Yang, C.-T.; Liang, J.; Huang, H.-L.; Kuo, L.-M.; Wu, C.-C.; Cheng, H.-S.; Chen, C.-Y.; Hsu, Y.-H.; Lee, P.-C.; et al. A family care model for older persons with hip fracture and cognitive impairment: A randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2021, 120, 103995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeili, M.; Dehghan Nayeri, N.; Bahramnezhad, F.; Fattah Ghazi, S.; Asgari, P. Effectiveness of a supportive program on caregiver burden of families caring for patients on invasive mechanical ventilation at home: An experimental study. Creat. Nurs. 2023, 29, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitek, D.E.; Erol, O. The effect of discharge training and telephone counseling service on patients’ functional status and caregiver burden after stroke: A randomized controlled trial. Neurol. Asia 2023, 28, 583–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, H.; Atkinson, C.; Bond, S.; Suddes, M.; Dobson, R.; Curless, R. Randomized controlled trial of a comprehensive stroke education program for patients and caregivers. Stroke 1999, 30, 2585–2591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.Y.; Chair, S.Y.; Chau, P.C. Effectiveness of a strength-oriented psychoeducation on caregiving competence, problem-solving abilities, psychosocial outcomes, and physical health among family caregivers of stroke survivors: A randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2018, 87, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakur, D.; Dhandapani, M.; Ghai, S.; Mohanty, M.; Dhandapani, S. Intracranial tumors: A nurse-led intervention for educating and supporting patients and their caregivers. Clin. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2019, 23, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vranceanu, A.-M.; Bannon, S.; Mace, R.; Lester, E.; Meyers, E.; Gates, M.; Popok, P.; Lin, A.; Salgueiro, D.; Tehan, T.; et al. Feasibility and efficacy of a resiliency intervention for the prevention of chronic emotional distress among survivor-caregiver dyads admitted to the neuroscience intensive care unit: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2020807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, M.; Harrow, A.; Donnan, P.; Davey, P.; Devereux, S.; Little, G.; McKenna, E.; Wood, R.; Chen, R.; Thompson, A. Patient, carer, and health service outcomes of nurse-led early discharge after breast cancer surgery: A randomized controlled trial. Br. J. Cancer 2004, 91, 651–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ganefianty, A.; Songwathana, P.; Damkliang, J.; Imron, A.; Latour, J.M. A Mobile Health Transitional Care Intervention Delivered by Nurses Improves Postdischarge Outcomes of Caregivers of Patients with Traumatic Brain Injury: A Randomized Controlled Trial. World Neurosurg. 2024, 184, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eames, S.; Hoffmann, T.; Worrall, L.; Read, S.; Wong, A. Randomized controlled trial of an education and support package for stroke patients and their carers. BMJ Open 2013, 3, e002538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vloothuis, J.D.M.; Mulder, M.; Nijland, R.H.M.; Goedhart, Q.S.; Konijnenbelt, M.; Mulder, H.; Hertogh, C.M.P.M.; van Tulder, M.; van Wegen, E.E.H.; Kwakkel, G. Caregiver-mediated exercises with e-health support for early supported discharge after stroke (CARE4STROKE): A randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE. 2019, 14, e0214241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindley, R.I.; Anderson, C.S.; Billot, L.; Forster, A.; Hackett, M.L.; Harvey, L.A.; Jan, S.; Li, Q.; Liu, H.; Langhorne, P.; et al. Family-led rehabilitation after stroke in India (ATTEND): A randomized controlled trial. Lancet 2017, 390, 588–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thodi, M.; Bistola, V.; Lambrinou, E.; Keramida, K.; Nikolopoulos, P.; Parissis, J.; Farmakis, D.; Filippatos, G. A randomized trial of a nurse-led educational intervention in patients with heart failure and their caregivers: Impact on caregiver outcomes. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2023, 22, 709–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahrokhi, A.; Azimian, J.; Amouzegar, A.; Oveisi, S. The Effect of Telenursing on Referral Rates of Patients with Head Trauma and Their Family’s Satisfaction after Discharge. J. Trauma Nurs. 2018, 25, 248–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, K.; Li, S. A WeChat-based caregiver education program improves satisfaction of stroke patients and caregivers, also alleviates poststroke cognitive impairment and depression: A randomized controlled study. Medicine 2022, 101, e29603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cossette, S.; Belaid, H.; Heppell, S.; Mailhot, T.; Guertin, M.C. Feasibility and acceptability of a nursing intervention with family caregiver on self-care among heart failure patients: A randomized pilot trial. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2016, 2, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, K.; Bu, X.; Sun, Z.; Wang, Y.; Feng, W.; Xiao, L.; Jiang, F.; Tang, X. Feasibility of a nurse-trained, family member-delivered rehabilitation model for disabled stroke patients in rural Chongqing, China. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2020, 29, 105382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alaei, A.; Babaei, S.; Farzi, S.; Hadian, Z. Effect of a supportive-educational program, based on COPE model, on quality of life and caregiver burden of family caregivers of heart failure patients: A randomized clinical trial study. BMC Nurs. 2024, 23, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, H.; Lam, S.K.K.; Chien, W.T. Effects of a family-focused dyadic psychoeducational intervention for stroke survivors and their family caregivers: A pilot study. BMC Nurs. 2022, 21, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, M.; Guest, C. Application of a multidimensional caregiver burden inventory. Gerontologist 1989, 29, 798–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmståhl, S.; Malmberg, B.; Annerstedt, L. Caregiver’s burden of patients 3 years after stroke assessed by a novel caregiver burden scale. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1996, 77, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, P.; Pion, S.; Klinkenberg, D.; Kuhrik, M.; Kuhrik, N. An instructional DVD fall-prevention program for patients with cancer and family caregivers. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2014, 41, 486–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalra, L.; Evans, A.; Perez, I.; Melbourn, A.; Patel, A.; Knapp, M.; Donaldson, N. Training carers of stroke patients: Randomized controlled trial. BMJ 2004, 328, 1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Téllez, A.; González-García, A.; Martín-Salvador, A.; Gázquez-López, M.; Martínez-García, E.; García-García, I. Humanization of nursing care: A systematic review. Front. Med. 2024, 26, 1446701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, E.H.; Austin, B.T.; Davis, C.; Hindmarsh, M.; Schaefer, J.; Bonomi, A. Improving chronic illness care: Translating evidence into action. Health Aff. 2001, 20, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marini, G.; Longhini, J.; Ambrosi, E.; Canzan, F.; Konradsen, H.; Kabir, Z.N. Transitional Care Interventions in Improving Patient and Caregiver Outcomes After Discharge: A Scoping Review. Healthcare 2025, 13, 312. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13030312

Marini G, Longhini J, Ambrosi E, Canzan F, Konradsen H, Kabir ZN. Transitional Care Interventions in Improving Patient and Caregiver Outcomes After Discharge: A Scoping Review. Healthcare. 2025; 13(3):312. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13030312

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarini, Giulia, Jessica Longhini, Elisa Ambrosi, Federica Canzan, Hanne Konradsen, and Zarina Nahar Kabir. 2025. "Transitional Care Interventions in Improving Patient and Caregiver Outcomes After Discharge: A Scoping Review" Healthcare 13, no. 3: 312. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13030312

APA StyleMarini, G., Longhini, J., Ambrosi, E., Canzan, F., Konradsen, H., & Kabir, Z. N. (2025). Transitional Care Interventions in Improving Patient and Caregiver Outcomes After Discharge: A Scoping Review. Healthcare, 13(3), 312. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13030312