A Community Advisory Board’s Role in Disseminating Tai Chi Prime in African American and Latinx Communities: A Pragmatic Application of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Community Advisory Boards

1.2. Applying CBPR to Inclusive Tai Chi Prime in Communities of Color

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sample

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. CAB Formation and Research Context

3.1.1. CFIR Domain 1: Individuals

- Construct 1: CAB Members Characteristics

- Construct 2: CAB Members’ Roles

3.1.2. CFIR Domain 2: Innovation

- Construct 1: Innovation Evidence-Based

- Construct 2: Innovation Adaptability

“Tai chi came from a different culture as well…So, that kind of gets you over that hurdle right at the get go because it’s [tai chi] always been trying to bridge the cultural gap.”—CAB 8.

3.2. CAB Process

3.2.1. CFIR Domain 3: Outer Setting

- Construct 1: Partnerships and Connections

“…we often host two interns in the first semester of the [university] school year. This year, the two assigned students did an amazing job just laying the landscape for places to share literature about tai chi. They did some mapping to see where senior housing is or was located and identified laundromats and grocery stores that those individuals may use as good marketing places for tai chi, so that was really good work done internally by those team members.”—CAB 3.

“We are also currently seeking funding from some of our already established funders whose values and missions align with the work of the Tai Chi Prime program.”—CAB 4.

- Construct 2: Financing

3.2.2. CFIR Domain 4: Inner Setting(s)

- Construct 1: Communication

“Block personal/agency calendars to secure regular attendance of AB1. PI to release meeting agenda out to the team 7–10 days prior to the next meeting.”—ABM #0 (kick-off meeting) by Study PI.

- Construct 2: Available Resources

“CORE has a room with mirrors and AV availability if we need to Zoom to virtual participants (although in-person training is preferred). Space needs: 6’ × 6’ per person = 36 sq ft/person. A 1000–1500 sq ft space could allow for 27–41 persons.”—ABM #1—July 2022.

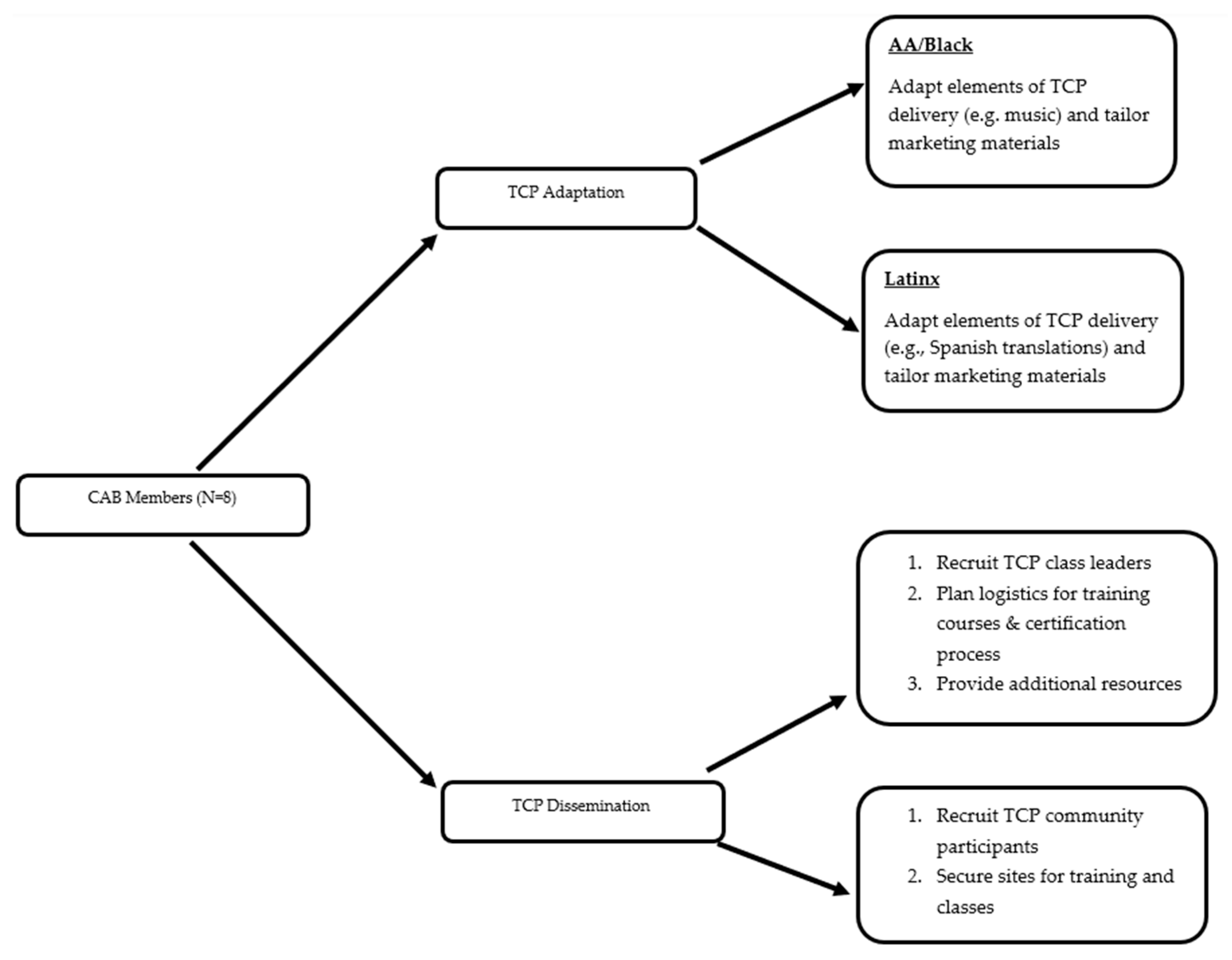

3.3. CAB Outcomes

3.3.1. CFIR Domain 5: Implementation Process

- Construct 1: Adaptation of Tai Chi Prime delivery

“We needed a promotional video to help us with this messaging, to give us more of a visual. We were able to take some of the [existing] templates and change out some pictures to be a little more local to the communities that were being presented…I thought that was wonderful.”—CAB 3.

“…when it comes to Tai Chi, there are certain terminologies that have to be changed to represent what Tai Chi principles are. So, you can’t be literal with some of the translations. That is one constraint when it comes to translation. The second constraint is we’re trying to appeal to the Spanish community, and the language is a little different. So, if they tried to translate it for Spanish people from Spain, it wouldn’t connect with people who are more Central American …We have a different type of linguistics and language. So, I thank God for [other group members], because they’re very good at that. We’ve had many discussions on how to change different things, in different contexts of the text.”—CAB 7.

“I think our advantage is that [the other team members] are fairly new to the country, so they’re more connected to the Spanish communities. They haven’t lived in America for too long, and I have been living away from South America for over 20 years. So, I sometimes feel like I’m forgetting my Spanish and the culture, but they are more connected to the culture than I am…they know not just slang words, but more colloquial types of communication in Spanish. And because the majority of Spanish speaking people here in Wisconsin are from Mexico, I think it comes in handy for sure.”—CAB 7.

“Marketing materials were provided in Spanish, so it was very helpful just to have something as a guide, and now they have handouts in Spanish…I think it provides a lot of comfort to the instructors knowing that they have resources that they can provide their students.”—CAB 1.

“The AA/Black Tai Chi Prime team is interested in a brief video to sell the nuances of the TCP program to their communities… [The AA/Black Tai Chi Prime team] is looking for a 1 to 2-min video with a voice over specific to the AA/Black community with tai chi demonstration including modifications going on in the background.”—ABM #12—June 2023.

“A rich discussion ensued about adaptations that may be needed for the African American community. CAB 5 stated that their tai chi practice group that has been meeting on Tuesdays and Friday nights explored using music (Miles Davis jazz) when doing basic moves training as a way of forming a cultural connection specific to the African American/black community.”—ABM #7—January 2023

“Music is a wonderful cultural adaptation that the Tai Chi Prime team feels both communities can readily explore and use with a few stipulations: (1) Don’t use music early in tai chi training as it can create cognitive (mental) overload when first learning the kinesthetic (movement) demands of tai chi; (2) it is best if used in summative sessions of silent guided Basic Moves or Form practice sessions, (3) Avoid music with any strong rhythm that might turn tai chi into a dance! Finally, CAB 8 brought up the issue of music rights which limits the ability of using musical recordings in public spaces.”—ABM #8—January 2023.

“Normally, people take a written exam and you just send them a PDF and they’re on their own to figure out how to fill it out and what to do, and so what we made was an adaptation. We took each question and put it on a single page and then said first you outline, then you describe, then you say in your own words, you know, summarize. So, the written exams were designed to help people have the language they need when they teach. We templated all those questions for them and gave them a couple of examples from the ROM [Tai Chi Health’s Range of Motion] dance, and then I gave them answers. This way, they would understand what we were looking for… we had no idea of the diversity of people we were attracting to train and where they were, from a comfort level, in dealing with written tests, and some of these folks were educated. They have master’s and bachelor’s degrees, but if they are older, they are out of school for years, right? So, we wanted to make that adaptation to help them feel comfortable doing written tests.”—PI.

3.3.2. Construct 2: Dissemination of Tai Chi Prime

“We supported in helping to identify community participants and facilitated the information through our network for community health workers… We had monthly check-ins with our workforce of community health workers to let them know about those opportunities, and we spoke at some churches that were being considered as host sites.”—CAB 3.

3.3.3. Construct 3: Reflection and Evaluation

4. Discussion

4.1. CAB Formation and Research Context: Individual Characteristics and Innovation Attributes

4.2. CAB Processes: Communication, Resources, and External Partnerships

4.3. CAB Outcomes: Adaptation and Dissemination

4.4. Extending CFIR for Community-Engaged Implementation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CBPR | Community-Based Participatory Research |

| CAB | Community Advisory Board |

| TCP | Tai Chi Prime |

| CFIR | Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research |

Appendix A

| PARTNER ORGANIZATIONS | ORGANIZATION DESCRIPTION | INDIVIDUALS NOMINATED TO SERVE ON CAB |

|---|---|---|

| CORE EL CENTRO | A Milwaukee-based non-profit organization that provides affordable natural healing and wellness services such as acupuncture, yoga, dance, cooking and herbalism workshops to people with little to no healthcare access. Classes are offered in English and Spanish. | Two individuals (one Executive Director and one staff health navigator) who also enrolled in the Tai Chi Prime leader training |

| UNITE WI | A non-profit that primarily serves the Milwaukee AA/Black community. The organization connects Community Health Workers (CHW) to people needing well-being programs, healthcare services, and social services. | One Executive Director |

| WALNUT WAY | Non-profit catering primarily to AA/Black and low-income families in Milwaukee. The organization offers various activities and programs to support community development, including wellness programs. | Two (one Grant Manager and one yoga instructor/Tai Chi Prime leader training candidate) |

| TAI CHI HEALTH | Purveyor of Tai Chi Prime. The organization offers several tai chi programs through its network of certified Yang-style trainers. Since its inception almost 50 years ago, the organization has trained over 10,000 students, including physical and occupational therapists. | Two (one Executive Director and one Spanish-speaking tai chi instructor) |

| ENHANCING BALANCE | Milwaukee-based tai chi and Tai Chi Prime instructor. Senior master trainer certified to train and assess fidelity of TCP leaders. | One Tai Chi Prime Master Trainer |

Appendix B

- Introduction

- Please introduce yourself and your role in your organization.

- Please describe your role in this project.

- Can you share details about your qualifications, training, and experience in teaching Tai Chi?

- What inspired you to introduce Tai Chi Prime to African American and Latinx communities?

- How did you get community buy-in for this project?

- What strategies did you employ to promote the training courses and generate interest in the community?

- 7.

- How did you tailor your recruitment efforts to appeal to a diverse range of participants with varying levels of familiarity with Tai Chi?

- 8.

- What qualifications or criteria did you use to select trainees for the leader pathway training?

- 9.

- Can you share any anecdotes or stories that highlight your experience planning and implementing this program?

- 10.

- How have you encouraged ongoing participation and engagement in the leader pathway training program

- 11.

- Have you observed any particular challenges or barriers to participant retention? If yes, how will you address these issues in the future? If not, why do you think that is?

- 12.

- How did you determine the appropriate class duration and frequency for optimal learning and practice?

- 13.

- What considerations were made in selecting the class location and setting?

- 14.

- As part of the advisory board, what kinds of cultural adaptations did your group make to make it more comfortable for the AA/Latinx community.

- 15.

- For master trainer: Can you provide insights into how you manage class size and ensure individual attention and guidance for participants?

- 16.

- What strategies or modifications did you make during the training to meet the needs of the participants?

- 17.

- What are your future plans for TCP?

- 18.

- What do you need from the research team to support your efforts to get more funding from govt or policy change?

- 19.

- What measures are in place to support trainers in offering tai chi prime to their communities in the future?

- 20.

- What advice would you give to others considering implementing a falls-prevention program such as Tai Chi Prime in African American/Black and Latinx communities?

- CLOSING QUESTION

References

- Belone, L.; Tosa, J.; Shendo, K.; Toya, A.; Straits, K.; Tafoya, G.; Rae, R.; Noyes, E.; Bird, D.; Wallerstein, N. Community-based participatory research for cocreating interventions with Native communities: A partnership between the University of New Mexico and the Pueblo of Jemez. In Evidence-Based Psychological Practice with Ethnic Minorities: Culturally Informed Research and Clinical Strategies; Zane, N., Bernal, G., Leong, F.T.L., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; pp. 199–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, S.E.; Clifasefi, S.L.; Stanton, J.; E Straits, K.J.; Gil-Kashiwabara, E.; Espinosa, P.R.; Nicasio, A.V.; Andrasik, M.P.; Hawes, S.M.; A Miller, K.; et al. Community-based participatory research (CBPR): Towards equitable involvement of community in psychology research. Am. Psychol. 2018, 73, 884–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, L.; Sullivan, C.; Joosten, Y.; Lipham, L.; Adams, S.; Coleman, P.; Carpenter, R.; Hargreaves, M. Advancing Community-Engaged Research through Partnership Development: Overcoming Challenges Voiced by Community-Academic Partners. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. 2020, 14, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langdon, S.E.; Golden, S.L.; Arnold, E.M.; Maynor, R.F.; Bryant, A.; Freeman, V.K.; Bell, R.A. Lessons Learned From a Community-Based Participatory Research Mental Health Promotion Program for American Indian Youth. Health Promot. Pract. 2016, 17, 457–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, C.M.; Bridges, K.M.; Ellerbeck, E.F.; Ablah, E.; Greiner, K.A.; Chen, Y.; Collie-Akers, V.; Ramírez, M.; LeMaster, J.W.; Sykes, K.; et al. Communities organizing to promote equity: Engaging local communities in public health responses to health inequities exacerbated by COVID-19-protocol paper. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1369777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeill, L.H.; Reitzel, L.R.; Escoto, K.H.; Roberson, C.L.; Nguyen, N.; Vidrine, J.I.; Strong, L.L.; Wetter, D.W. Engaging Black Churches to Address Cancer Health Disparities: Project CHURCH. Front. Public Health 2018, 6, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiyanbola, O.O.; Kaiser, B.L.; Thomas, G.R.; Tarfa, A. Preliminary engagement of a patient advisory board of African American community members with type 2 diabetes in a peer-led medication adherence intervention. Res. Involv. Engagem. 2021, 7, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barwise, A.K.; Egginton, J.; Pacheco-Spann, L.; Clift, K.; Albertie, M.; Johnson, M.; Batbold, S.; Phelan, S.; Allyse, M. Community engaged research to measure the impact of COVID-19 on vulnerable community member’s well-being and health: A mixed methods approach. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 2023, 135, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallerstein, N.; Duran, B. Community-based participatory research contributions to intervention research: The intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. Am. J. Public Health 2010, 100, S40–S46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safo, S.; Cunningham, C.; Beckman, A.; Haughton, L.; Starrels, J.L. “A place at the table”: A qualitative analysis of community board members’ experiences with academic HIV/AIDS research. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2016, 16, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang Yan, C.; Haque, S.; Chassler, D.; Lobb, R.; Battaglia, T.; Sprague Martinez, L. “It has to be designed in a way that really challenges people’s assumptions”: Preparing scholars to build equitable community research partnerships. J. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2021, 5, e182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallerstein, N.; Muhammad, M.; Sanchez-Youngman, S.; Espinosa, P.R.; Avila, M.; Baker, E.A.; Barnett, S.; Belone, L.; Golub, M.; Lucero, J.; et al. Power Dynamics in Community-Based Participatory Research: A Multiple-Case Study Analysis of Partnering Contexts, Histories, and Practices. Health Educ. Behav. 2019, 46, 19S–32S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salsberg, J.; Parry, D.; Pluye, P.; Macridis, S.; Herbert, C.P.; Macaulay, A.C. Successful strategies to engage research partners for translating evidence into action in community health: A critical review. J. Environ. Public Health 2015, 2015, 191856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, S.D.; Andrews, J.O.; Magwood, G.S.; Jenkins, C.; Cox, M.J.; Williamson, D.C. Community advisory boards in community-based participatory research: A synthesis of best processes. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2011, 8, A70. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, G.; Kettaneh, H.; Knox, B.; Purkey, E.; Chan-Nguyen, S.; Jenkins, M.; Bayoumi, I. Engaging people with lived experiences on community advisory boards in community-based participatory research: A scoping review protocol. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e078479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyons, M.J.; Fernandez Poole, S.; Brownson, R.C.; Lyn, R. Place Is Power: Investing in Communities as a Systemic Leverage Point to Reduce Breast Cancer Disparities by Race. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockman, T.A.; Balls-Berry, J.E.; West, I.W.; Valdez-Soto, M.; Albertie, M.L.; Stephenson, N.A.; Omar, F.M.; Moore, M.; Alemán, M.; Berry, P.A.; et al. Researchers’ experiences working with community advisory boards: How community member feedback impacted the research. J. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2021, 5, e117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domecq, J.P.; Prutsky, G.; Elraiyah, T.; Wang, Z.; Nabhan, M.; Shippee, N.; Brito, J.P.; Boehmer, K.; Hasan, R.; Firwana, B.; et al. Patient engagement in research: A systematic review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Council on Aging. Evidence-Based Program: Tai Chi Prime. 27 November 2023. Available online: https://www.ncoa.org/article/evidence-based-program-tai-chi-prime/ (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Yu, T.; Hallisy, K. Tai Chi Fundamentals® Adapted Program with Optional Side Support, Walker Support, and Seated Versions; Uncharted Country Publishing: Arroyo Seco, NM, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chewning, B.; Hallisy, K.M.; Mahoney, J.E.; Wilson, D.; Sangasubana, N.; Gangnon, R. Disseminating Tai Chi in the Community: Promoting Home Practice and Improving Balance. Gerontologist 2020, 60, 765–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, J.E.; Pinzon, M.M.; Myers, S.; Renken, J.; Eggert, E.; Palmer, W. The Community-Academic Aging Research Network: A Pipeline for Dissemination. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2020, 68, 1325–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleinheksel, A.J.; Rockich-Winston, N.; Tawfik, H.; Wyatt, T.R. Demystifying Content Analysis. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2020, 84, 7113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindgren, B.-M.; Lundman, B.; Graneheim, U.H. Abstraction and interpretation during the qualitative content analysis process. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2020, 108, 103632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhakal, K. NVivo. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. 2022, 110, 270–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaismoradi, M.; Turunen, H.; Bondas, T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs. Health Sci. 2013, 15, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breimaier, H.E.; Heckemann, B.; Halfens, R.J.; Lohrmann, C. The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR): A useful theoretical framework for guiding and evaluating a guideline implementation process in a hospital-based nursing practice. BMC Nurs. 2015, 14, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, M.A.; Kelley, C.; Yankey, N.; Birken, S.A.; Abadie, B.; Damschroder, L. A systematic review of the use of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. Implement. Sci. 2016, 11, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, A.; Kajamaa, A.; Johnston, J. How to … be reflexive when conducting qualitative research. Clin. Teach. 2020, 17, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmos-Vega, F.M.; Stalmeijer, R.E.; Varpio, L.; Kahlke, R. A practical guide to reflexivity in qualitative research: AMEE Guide No. 149. Med. Teach. 2022, 45, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, C.; Janes, G.; Williams, J. Identity, positionality and reflexivity: Relevance and application to research paramedics. Br. Paramed. J. 2022, 7, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, J.L.; Adkins, D.; Chauvin, S. A Review of the Quality Indicators of Rigor in Qualitative Research. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2020, 84, 7120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salihu, E.Y.; Hallisy, K.; Baidoo, S.; Malta, J.S.; Ferrill, C.; Melgoza, F.; Sandretto, R.; Culotti, P.C.; Chewning, B. Feasibility and Acceptability of a “Train the Leader” Model for Disseminating Tai Chi Prime with Fidelity in African American/Black and Latinx Communities: A Pilot Mixed-Methods Implementation Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Key, K.D.; Furr-Holden, D.; Lewis, E.Y.; Cunningham, R.; Zimmerman, M.A.; Johnson-Lawrence, V.; Selig, S. The Continuum of Community Engagement in Research: A Roadmap for Understanding and Assessing Progress. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. 2019, 13, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, A.A.; Peña, M.K.S.; Cardona, J.A.D.; Marín, S.M.G.; Londoño, G.C.; Vargas, C.E. Social Participation in Health: A Community-Based Participatory Research Approach to Capacity Building in Two Colombian Communities. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. 2022, 16, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadler, L.S.; Larson, J.; Bouregy, S.; LaPaglia, D.; Bridger, L.; McCaslin, C.; Rockwell, S. Community-university partnerships in community-based research. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. 2012, 6, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, K.A.; Goodman, L.A.; Vainer, E.S.; Heimel, D.; Barkai, R.; Collins-Gousby, D. “No Sacred Cows or Bulls”: The Story of the Domestic Violence Program Evaluation and Research Collaborative (DVPERC). J. Fam. Violence 2018, 33, 537–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paskett, E.D.; Reeves, K.W.; McLaughlin, J.M.; Katz, M.L.; McAlearney, A.S.; Ruffin, M.T.; Halbert, C.H.; Merete, C.; Davis, F.; Gehlert, S. Recruitment of minority and underserved populations in the United States: The Centers for Population Health and Health Disparities experience. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2008, 29, 847–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitt-Glover, M.C.; Borden, S.L.; Alexander, D.S.; Kennedy, B.M.; Goldmon, M.V. Recruiting African American Churches to Participate in Research: The Learning and Developing Individual Exercise Skills for a Better Life Study. Health Promot. Pract. 2016, 17, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Clark, J.K.; Schmiesing, R.; Kaiser, M.L.; Reece, J.; Park, S. Perspectives of community members on community-based participatory research: A systematic literature review. J. Urban Aff. 2024, 47, 2916–2935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Liu, Y.; Peng, C.; Shen, T.; Du, B.; Yi, L. Physical and psychological impacts of Tai Chi on college students and the determination of optimal dose: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur. J. Integr. Med. 2025, 76, 102450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Zhou, B.; Wen, Z.; Zhang, Y. From healing and martial roots to global health practice: Reimagining Tai Chi (Taijiquan) in the modern public fitness movement. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1677470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fehlberg, Z.; Klaic, M.; Croy, S.; Best, S. Narrowing the health equity gap. How can implementation science proactively facilitate the cultural adaptation of public health innovations? Verringerung der Ungleichheit in der Gesundheitsversorgung. Wie kann die Implementierungswissenschaft die kulturelle Anpassung von Innovationen im Bereich der öffentlichen Gesundheit proaktiv erleichtern? Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2025, 68, 809–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrieta, J.; Wuerth, M.; Aoun, M.; Bemme, D.; D’SOuza, N.; Gumbonzvanda, N.; Esponda, G.M.; Roberts, T.; Yoder-Maina, A.; Zamora, E.; et al. Equitable and sustainable funding for community-based organisations in global mental health. Lancet Glob. Health 2023, 11, e327–e328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodward, E.N.; Matthieu, M.M.; Uchendu, U.S.; Rogal, S.; Kirchner, J.E. The health equity implementation framework: Proposal and preliminary study of hepatitis C virus treatment. Implement. Sci. 2019, 14, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safaeinili, N.; Brown-Johnson, C.; Shaw, J.G.; Mahoney, M.; Winget, M. CFIR simplified: Pragmatic application of and adaptations to the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) for evaluation of a patient-centered care transformation within a learning health system. Learn. Health Syst. 2019, 4, e10201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, M.; Wilhelm, A.; Ortega, L.E.; Pergament, S.; Bates, N.; Cunningham, B. Applying a Race(ism)-Conscious Adaptation of the CFIR Framework to Understand Implementation of a School-Based Equity-Oriented Intervention. Ethn. Dis. 2021, 31, 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faissner, M.; Braun, E.; Efkemann, S.A.; Gaillard, A.-S.; Haferkemper, I.; Hempeler, C.; Heuer, I.; Lux, U.; Potthoff, S.; Scholten, M.; et al. Establishing a peer advisory board in a mental health ethics research group—Challenges, benefits, facilitators and lessons learned. Front. Psychiatry 2025, 16, 1516996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reardon, C.M.; Damschroder, L.J.; Ashcraft, L.E.; Kerins, C.; Bachrach, R.L.; Nevedal, A.L.; Domlyn, A.M.; Dodge, J.; Chinman, M.; Rogal, S. The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) User Guide: A five-step guide for conducting implementation research using the framework. Implement. Sci. 2025, 20, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damschroder, L.J.; Reardon, C.M.; Widerquist, M.A.O.; Lowery, J. The updated Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research based on user feedback. Implement. Sci. 2022, 17, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Project Stage | CFIR Domains | Subdomains/Constructs | Themes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cab Formation and Research Context | Individuals | CAB Members’ Characteristics | CAB Members’ organizations are embedded and respected in the communities they serve |

| Pre-existing relationship between CAB members’ organizations | |||

| CAB Members Roles | CAB members ensured cultural fit of the program | ||

| CAB members supported program logistics and program delivery | |||

| Innovation | Evidence-Base | Existing evidence supporting Tai Chi Prime as a fall prevention program and potential for other health benefits | |

| Adaptability | TCP’s history reflects its adaptability for different cultural contexts | ||

| Cab Process | Outer Setting | Partnerships and Connections | Leveraging partnerships and resources from other institutions |

| Financing | Navigating Funding Constraints Through Collaborative Problem-Solving | ||

| Inner Setting | Communication | Monthly CAB meetings to ensure consistent communication | |

| Available Resources | Leveraging organization resources to support program delivery | ||

| Cab Outcomes | Implementation | Adaptation of TCP delivery | General tailoring of marketing materials to meet communities’ needs |

| Adaptation of TCP delivery for Latinx community | |||

| Adaptation of TCP delivery for AA/Black community | |||

| Adaptations made to the TCP leader certification process | |||

| Dissemination of TCP | Recruitment of TCP class leaders | ||

| Recruitment of community TCP participants | |||

| Reflection and Evaluation | Facilitators of CAB engagement:

| ||

Barriers to CAB engagement

| |||

| TCP = Tai Chi Prime | |||

| Themes | Subthemes | Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Facilitators of CAB Engagement | Acknowledgement of CAB members’ expertise and co-ownership of project | “If you’re working with these organizations, you have to involve them when you’re writing the grant. You have to really listen carefully, [and] take what they’re willing to teach you. You just have to be humble [and] recognize how little you know.”—Co-PI “…as a community partner, there is just this unconscious inferiority because it’s academia and community-based partners. I think that’s really important when the researchers make all parties at the table feel really comfortable with their role, with their capacity, with what they bring to the table…that’s really important. I think that was demonstrated here.”—CAB 3 |

| Prioritization of community needs alongside research needs | “I thought this was an amazing team and leadership…it was great opportunity to work and from beginning to end see how we were able to talk about what the community needs were, what the program needs were and blending that well.”—CAB 1 | |

| Provision of additional resources to support program post-study completion | “We have funds left in the [grant] to help support the advancement of teaching skills among the new Tai Chi Prime leaders. We agreed to $30 per session going forward.”—ABM #21,March 2024 “We (researchers) encourage our Milwaukee Community Partner leaders, and the Tai Chi Prime leader representatives to reach out for grant writing assistance.”—ABM #22,April 2024 | |

| Barriers to CAB Engagement | Insufficient funds to support all aspects of the project | “[The research team] has discussed a few places where we could trim some budget, but this might take some creativity from all of us.”—ABM #0 (kick-off meeting)—June 2022 |

| Initial reluctance by community members while recruiting trainees and community participants | “There are misunderstandings about Eastern medicine in some communities, particularly in Christian-based communities. Some of the older generations may not be so familiar, so they don’t quite understand what the movements represent.”—CAB 3 | |

| Extra workload navigating payment for different entities and individuals | “[PI] has had some difficulty in getting all the paperwork filed related to the various payee components of the grant. Extra PO work had to be done because some groups on this team are being paid more than $5000 given their roles and this required extra justifications.” ABM #5,November 2022 | |

| Limited resources in community-based organizations | “If we had more capacity, we would call people [to remind them of class] if we could, but we don’t.”—CAB 1 “As a community-based, organic, small emerging organization, it’s been a little bit of a learning curve for us trying to manage all of the responsibilities of the day-to-day operations while also managing turnover. I speak to that because it is impeding our ability to have consistent invoicing for the project.”—CAB 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Salihu, E.Y.; Hallisy, K.; Malta, J.S.; Joseph, D.T.; Ferrill, C.; Culotti, P.C.; Juarez, R.H.; Chewning, B. A Community Advisory Board’s Role in Disseminating Tai Chi Prime in African American and Latinx Communities: A Pragmatic Application of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. Healthcare 2025, 13, 3307. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243307

Salihu EY, Hallisy K, Malta JS, Joseph DT, Ferrill C, Culotti PC, Juarez RH, Chewning B. A Community Advisory Board’s Role in Disseminating Tai Chi Prime in African American and Latinx Communities: A Pragmatic Application of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. Healthcare. 2025; 13(24):3307. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243307

Chicago/Turabian StyleSalihu, Ejura Yetunde, Kristine Hallisy, Jéssica S. Malta, Deborah Tolani Joseph, Cheryl Ferrill, Patricia Corrigan Culotti, Rebeca Heaton Juarez, and Betty Chewning. 2025. "A Community Advisory Board’s Role in Disseminating Tai Chi Prime in African American and Latinx Communities: A Pragmatic Application of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research" Healthcare 13, no. 24: 3307. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243307

APA StyleSalihu, E. Y., Hallisy, K., Malta, J. S., Joseph, D. T., Ferrill, C., Culotti, P. C., Juarez, R. H., & Chewning, B. (2025). A Community Advisory Board’s Role in Disseminating Tai Chi Prime in African American and Latinx Communities: A Pragmatic Application of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. Healthcare, 13(24), 3307. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243307