Correlation of Eye Diseases with Odontogenic Foci of Infection: A Case Report Using Infrared Thermography as a Diagnostic Adjunct

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Case Presentation

2.1. Interview

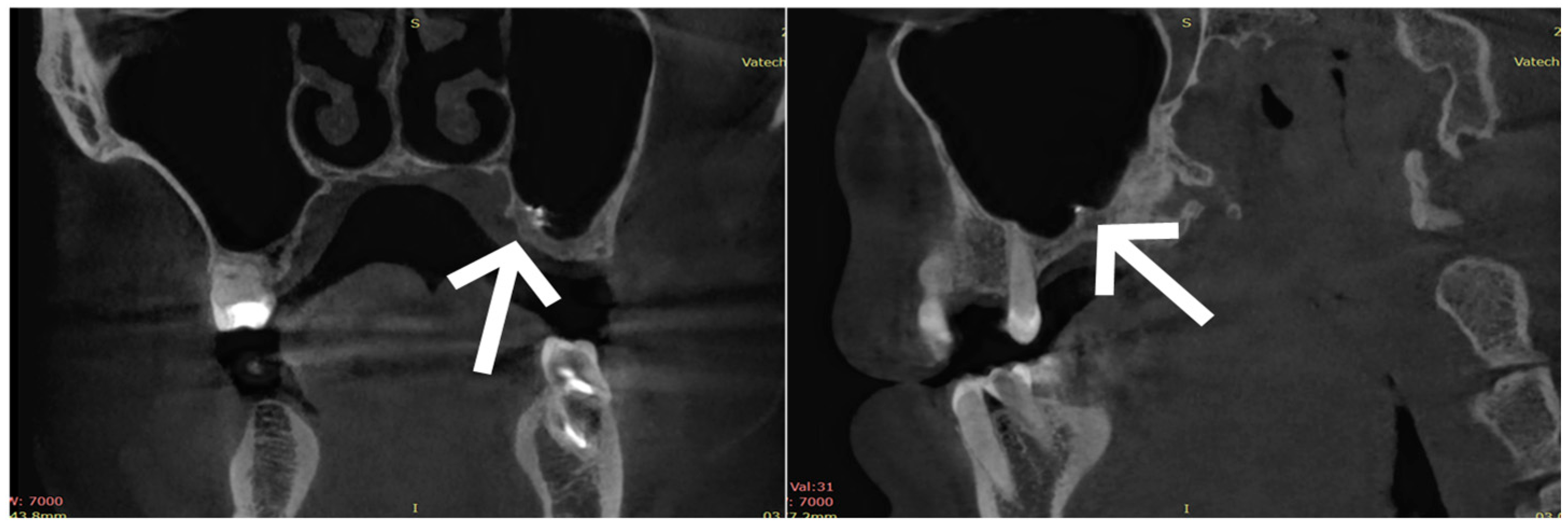

2.2. Dental Diagnostic Examination

2.3. Treatment

2.4. Outcome and Follow-Up

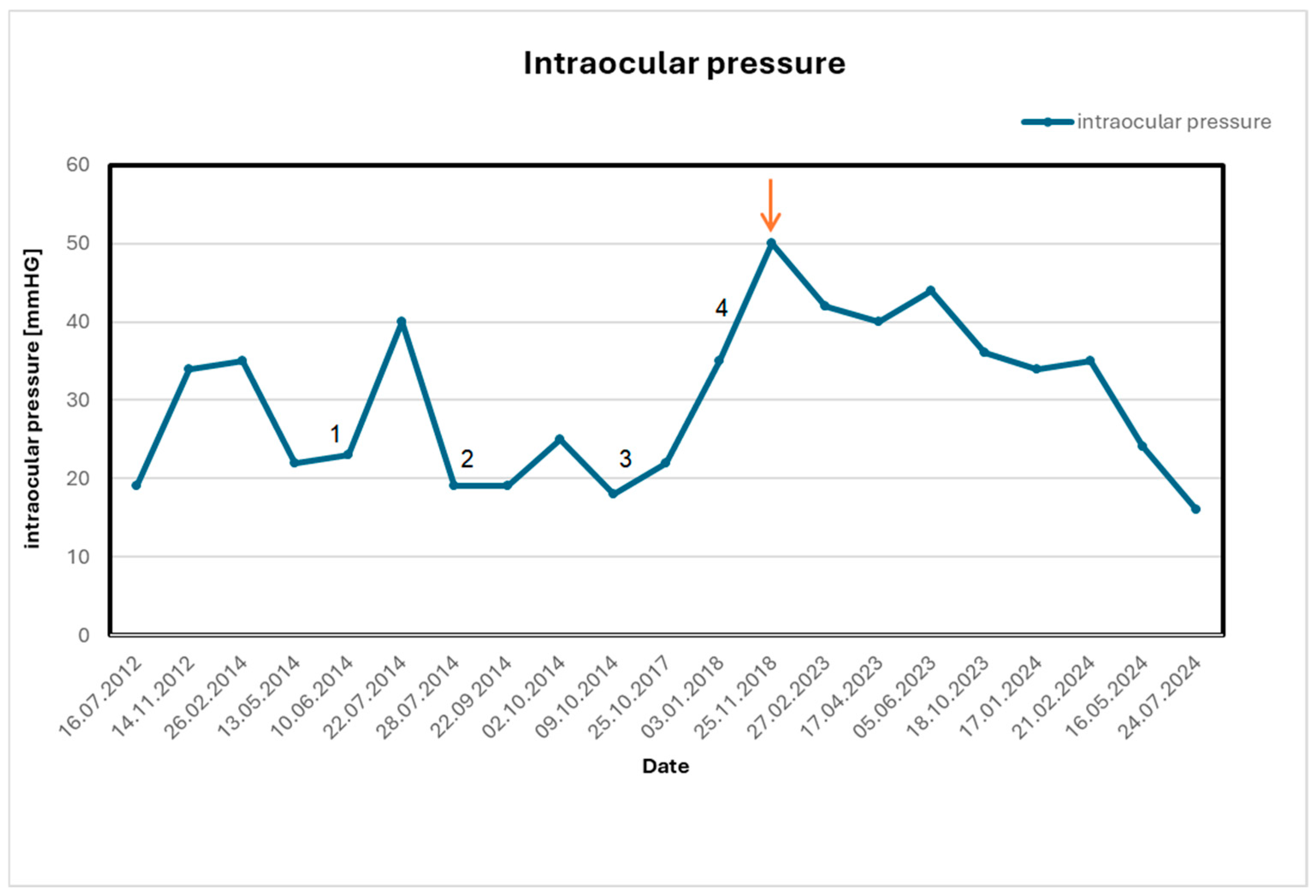

2.5. Ophthalmological Results and Long-Term Follow-Up

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Niedzielska, I.; Wziątek-Kuczmik, D. Wpływ zębopochodnych ognisk infekcji na choroby innych narządów—Przegląd piśmiennictwa (The impact of dental foci of infection on diseases of other organs—A review of the literature). Chir. Pol. 2007, 9, 92–96. [Google Scholar]

- Wapniarska, K.; Zielińska, R. Współczesne poglądy na ogniska zakażenia w jamie ustnej jako źródło chorób ogólnoustrojowych (Contemporary views on foci of infection in the oral cavity as a source of systemic diseases). Mag. Stomatol. 2015, 25, 89–96. [Google Scholar]

- Piekoszewska-Ziętek, P.; Turska-Szybka, A.; Olczak-Kowalczyk, D. Infekcje zębopochodne—Przegląd piśmiennictwa (Dental infections—A review of the literature). Nowa Stomatol. 2016, 21, 120–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weise, H.; Naros, A.; Weise, C.; Reinert, S.; Hoefert, S. Severe odontogenic infections with septic progress—A constant and increasing challenge: A retrospective analysis. BMC Oral Health 2019, 19, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nashawi, F.E.; Alkheder, A.; Shasho, H.O.; Abdullah, L.; Mohsen, A.B.A. An unusual route of odontogenic infection from the mandible to the orbit through the facial spaces, resulting in blindness: A rare case report. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2023, 2023, rjad457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammer, K.; Ring, F. The Thermal Human Body: A Practical Guide to Thermal Imaging, 1st ed.; Jenny Stanford Publishing: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahiri, B.B.; Bagavathiappan, S.; Jayakumar, T.; Philip, J. Medical applications of infrared thermography: A review. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2012, 55, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CareQuest Institute for Oral Health. Medical-Dental Integration. Available online: https://www.carequest.org/topics/medical-dental-integration (accessed on 24 November 2024).

- Preda, M.A.; Sarafoleanu, C.; Mușat, G.; Preda, A.-A.; Lupoi, D.; Barac, R.; Pop, M. Management of oculo-orbital complications of odontogenic sinusitis in adults. Rom. J. Ophthalmol. 2024, 68, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.H.; Kim, J.; Kang, M.G.; Lee, D.H.; Chin, H.S.; Jang, T.Y.; Kim, N.R. Optic nerve changes in chronic sinusitis patients: Correlation with disease severity and relevant sinus location. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0199875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nien, C.-W.; Lee, C.-Y.; Wu, P.-H.; Chen, H.-C.; Chi, J.C.-Y.; Sun, C.-C.; Huang, J.-Y.; Lin, H.-Y.; Yang, S.-F. The development of optic neuropathy after chronic rhinosinusitis: A population-based cohort study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0220286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yevchev, F.D.; Yepisheva, S.M.; Diachkova, Z.E.; Tereshchenko, A.A. Optic neuritis as a complication of inflammatory pathology of the paranasal sinuses. Arch. Ukr. Ophthalmol. 2025, 13, 129–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, L.E.; Margo, C.E.; Roetzheim, R.G. Uveitis: The collaborative diagnostic evaluation. Am. Fam. Physician 2014, 90, 711–716. [Google Scholar]

- Barisani-Asenbauer, T.; Maca, S.M.; Mejdoubi, L.; Emminger, W.; Machold, K.; Auer, H. Uveitis—A rare disease often associated with systemic diseases and infections: A systematic review of 2619 patients. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2012, 7, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saccà, S.C.; Bagnis, A.; Traverso, C.E. Bilateral Acute Anterior Uveitis from Sinusitis Complicated by Optic Disc Oedema in a Child: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2017, 3, 015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Low, T.H.; Seah, J.J.; Subramaniam, S.; Thirunavukarasu, V.; Ng, C.L. Bleach-induced chemical sinusitis and orbital cellulitis following root canal treatment. Sinusitis 2023, 7, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.C.; Zhao, C.; Wu, K.Y.; Marchand, M. Ophthalmic complications after dental procedures: Scoping review. Diseases 2025, 13, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sève, P.; Cacoub, P.; Bodaghi, B.; Trad, S.; Sellam, J.; Bellocq, D.; Bielefeld, P.; Sène, D.; Kaplanski, G.; Monnet, D.; et al. Uveitis: Diagnostic work-up. A literature review and recommendations from an expert committee. Autoimmun. Rev. 2017, 16, 1254–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernard, A.; Seve, P.; Abukhashabh, A.; Roure-Sobas, C.; Boibieux, A.; Denis, P.; Broussolle, C.; Mathis, T.; Kodjikian, L. Lyme-associated uveitis: Clinical spectrum and review of literature. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 30, 874–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lippert, J.; Falgiani, M.; Ganti, L. Posner–Schlossman syndrome. Cureus 2020, 12, e6584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, K.; Konana, V.K.; Ganesh, S.K.; Patnaik, G.; Chan, N.S.W.; Chee, S.P.; Sobolewska, B.; Zierhut, M. Viral anterior uveitis. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 68, 1764–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laboratory Testing for Uveitis: Making Smart Decisions. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Available online: https://www.aao.org (accessed on 11 October 2023).

- Sijssens, K.M.; Rijkers, G.T.; Rothova, A.; Stilma, J.S.; de Boer, J.H. Distinct Cytokine Patterns in the Aqueous Humor of Children, Adolescents and Adults with Uveitis. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2008, 16, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlosser, R.J.; Gage, S.E.; Kohli, P.; Soler, Z.M. Burden of illness: A systematic review of depression in chronic rhinosinusitis. Am. J. Rhinol. Allergy 2016, 30, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Liu, L.; Wang, Y.; Hu, K.; Ma, B.; Chi, J. Prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Otolaryngol.–Head Neck Surg. 2023, 168, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naletilić, N.; Pondeljak, N.; Lugović-Mihić, L.; Trkulja, V.; Kalogjera, L. Association between symptom severity and intensity of acute psychological distress in newly diagnosed patients with chronic rhinitis and chronic rhinosinusitis. Acta Clin. Croat. 2023, 62, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Ko, I.; Kim, M.S.; Yu, M.S.; Cho, B.J.; Kim, D.K. Association of chronic rhinosinusitis with depression and anxiety in a nationwide insurance population. JAMA Otolaryngol.–Head Neck Surg. 2019, 145, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chudecka, M.; Lubkowska, A. The use of thermal imaging to evaluate body temperature changes of athletes during training and a study on the impact of physiological and morphological factors on skin temperature. Hum. Mov. 2012, 13, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakhunde, M.B.; Gotarkar, S.; Choudhari, S.G. Thermography as a breast cancer screening technique: A review article. Cureus 2022, 14, e31251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philip, J.; Bagavathiappan, S.; Saravanan, T.; Jayakumar, T.; Raj, B.; Karunanithi, R.; Panicker, T.; Korath, M.P.; Jagadeesan, K. Infrared thermal imaging for detection of peripheral vascular disorders. J. Med. Phys. 2009, 34, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wziątek-Kuczmik, D.; Niedzielska, I.; Mrowiec, A.; Bałamut, K.; Handzel, M.; Szurko, A. Is thermal imaging a helpful tool in diagnosis of asymptomatic odontogenic infection foci? A pilot study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mrowiec, A.; Świątkowski, A.; Wolnica, K.; Cholewka, A.; Niedzielska, I.; Wziątek-Kuczmik, D. The use of thermovision in the detection of asymptomatic facial inflammation—Pilot study. Pol. J. Med. Phys. Eng. 2024, 30, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedzielska, I.; Pawelec, S.; Puszczewicz, Z. The employment of thermographic examinations in the diagnostics of diseases of the paranasal sinuses. Dentomaxillofac. Radiol. 2017, 46, 20160367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Measurement | Maxillary Sinus | Average Temperature [°C] at 30 s |

|---|---|---|

| The first measurement | Left maxillary sinus | 36.1 |

| Right maxillary sinus | 35 | |

| Difference average temperaturę | 1.1 | |

| The second measurement | Left maxillary sinus | 35.2 |

| Right maxillary sinus | 35 | |

| Difference average temperature | 0.2 | |

| The third measurement | Left maxillary sinus | 34.3 |

| Right maxillary sinus | 34.3 | |

| Difference average temperature | 0 | |

| The fourth measurement | Left maxillary sinus | 32.5 |

| Right maxillary sinus | 32.4 | |

| Difference average temperature | 0.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wziątek-Kuczmik, D.; Mrowiec, A.; Lorenc, A.; Kamiński, M.; Niedzielska, I.; Mrukwa-Kominek, E.; Cholewka, A. Correlation of Eye Diseases with Odontogenic Foci of Infection: A Case Report Using Infrared Thermography as a Diagnostic Adjunct. Healthcare 2025, 13, 3283. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243283

Wziątek-Kuczmik D, Mrowiec A, Lorenc A, Kamiński M, Niedzielska I, Mrukwa-Kominek E, Cholewka A. Correlation of Eye Diseases with Odontogenic Foci of Infection: A Case Report Using Infrared Thermography as a Diagnostic Adjunct. Healthcare. 2025; 13(24):3283. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243283

Chicago/Turabian StyleWziątek-Kuczmik, Daria, Aleksandra Mrowiec, Anna Lorenc, Maciej Kamiński, Iwona Niedzielska, Ewa Mrukwa-Kominek, and Armand Cholewka. 2025. "Correlation of Eye Diseases with Odontogenic Foci of Infection: A Case Report Using Infrared Thermography as a Diagnostic Adjunct" Healthcare 13, no. 24: 3283. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243283

APA StyleWziątek-Kuczmik, D., Mrowiec, A., Lorenc, A., Kamiński, M., Niedzielska, I., Mrukwa-Kominek, E., & Cholewka, A. (2025). Correlation of Eye Diseases with Odontogenic Foci of Infection: A Case Report Using Infrared Thermography as a Diagnostic Adjunct. Healthcare, 13(24), 3283. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243283