Abstract

Background/Objectives: Cervical cancer is the second most common gynecological cancer worldwide, preventable through screening initiatives and vaccinations against its causative agent, anogenital human papillomavirus (HPV). This study aimed at measuring the coverage and uptake of the national HPV vaccination program launched in 2023 and implemented throughout Poland. Methods: This cross-sectional, observational study analyzed population data of adolescents in 11–13-year-old groups vaccinated in individual voivodeships (provinces) of Poland as provided by the National Health Fund and the Central Statistical Office. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Results: The rate of HPV vaccination participation under the population program was 8.67%. In the analyzed age groups, in both sexes, no statistically significant correlation was observed between the population size at a given age and population coverage or participation in HPV vaccination. However, a positive relationship in vaccination coverage was observed in individuals previously vaccinated with one dose in subsequent age groups, indicating a continued willingness to receive vaccination with further doses. No statistically significant difference in population coverage changes across voivodeships was found between the number of doses within the urban population share vs. rural population share. Conclusions: Our results show that, at 1.5 years of implementation of the national HPV vaccination program, the coverage and uptake of the program is considerably insufficient. The intensive corrective actions indicated are required to pave this program forward towards optimum results.

1. Introduction

Vaccinations serve as a source of long-term protection and prevention against various diseases. The significance of vaccination in the robust eradication of infectious agents is considered a paradigm shift, saving millions of lives worldwide [1,2].

Cervical cancer is the fourth most common gynecological cancer in women worldwide, with approximately 600,000 new cases and 350,000 deaths reported globally in year 2022 [3,4]. The major causative agent for cervical cancer (approximately 80% of the cases) is attributed to human papillomavirus (HPV). Moreover, this virus has also been associated with benign genital warts, and vulvar, vaginal, anal, penile, and laryngeal cancers. Fortunately, robust screening and vaccination initiatives against both low-risk (LR) and high-risk (HR) HPV virus strains have proved to serve as robust preventive measures, helping to reduce the burden of cervical as well as its associated cancers globally [5,6,7]. Among the high-risk (HR) HPV types, HPV-16 and -18 are considered highly carcinogenic due to their expression of oncoproteins E6 and E7. These viral oncoproteins initiate uncontrolled cell cycle progression via the disruption of signaling pathways associated with p53 and pRB tumor suppressor proteins. Persistent HR HPV infection with overexpression of E6 and E7 initially leads to precancerous changes in the cervical epithelium, known as cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN), that further progress to invasive cervical cancer, ultimately spreading to the uterus, bladder, rectum, and pelvic lymph nodes [8].

Regardless of an individual’s HPV test result (positive or negative), or history of cervical conization, vaccination against HPV has been reported to increase the local immune response against the virus, thus preventing disease recurrence by eradicating viral replication [9]. Worldwide, HPV eradication through vaccinations has clearly demonstrated an advantage via cancer risk reduction, consequently leading to a reduction in treatment and hospital-associated burden on both the government and the affected individuals [10,11].

According to the Catalan Institute of Oncology/International Agency for Research on Cancer (ICO/IARC) data, Poland has reported that approximately 3.4% of cervical infection cases in women are associated with HPV-16 and/or HPV-18. On the other hand, 88.1% of reported invasive cervical cancers have been attributed to HPV-16 or -18 strains, indicating the high risk associated with the respective HPV types [12].

In 2020, the WHO adopted the 90–70–90 target for 2030 that aims to reduce the incidence of HPV-associated cervical cancers. The target is geared towards the following goals: 90% of girls to be fully vaccinated with the HPV vaccine by the age of 15, 70% of women screened using a high-performance test by the age of 35, and again by the age of 45, and lastly, 90% of women with pre-cancerous lesions treated and 90% of women with invasive cancer managed with minimally invasive interventions [13]. According to this WHO strategy, a two-dose HPV vaccination has been recommended if the first dose is administered under 15 years of age. Several countries have already adopted this strategy in the context of compliance and cost reduction [14,15]. In recent years, however, sentiment around population-based HPV vaccination has cooled somewhat. In Japan, HPV vaccination has been suspended in recent years due to adverse events (such as cerebral vasculitis), which in turn has caused a decline in HPV vaccination coverage in other countries participating in the WHO program [16]. It is worth noting, that WHO, along with non-WHO institutions (like The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation), fight for enhancing attitudes around HPV vaccines. There have also been studies suggesting that vaccination with a single dose of the vaccine may be sufficient [17].

Furthermore, clinical trials, large-scale studies, and real-world data have documented that the effectiveness of the HPV vaccine, with one or more doses administered, ranges from 83.0% to 96.1%. On the other hand, an approximate 90% reduction in type 6, 11, 16, and 18 HPV infections and a nearly 90% reduction in cervical cancer incidence among girls vaccinated before the age of 17 have been reported in several countries that adopted the WHO recommendations on vaccination strategy [18,19]. Similarly, the quadrivalent HPV vaccine has been reported to effectively prevent high-grade cervical lesions, supporting its role in preventing invasive cervical cancer [19,20,21].

In Poland, population-based HPV vaccination was launched as a national immunization program in June 2023 with the Cervarix® (quadrivalent anti-HPV vaccine, GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals S.A., Rixensart, Belgium) and Gardasil 9® (nine-valent anti-HPV vaccine, Merck Sharp & Dohme B.V., Haarlem, The Netherlands) vaccines available free of cost to the public [22,23]. At the end of August 2023, a total of 83,782 teenagers were vaccinated (65% girls, 35% boys, with an age bracket of 12–13 years) within the free HPV vaccination program. The vaccination share was at 9.8%, which was considered low [24]. According to Eurostat, administrative data from cervical screening programs available for 20 European Union (EU) countries, cervical cancer screening percentage has ranged from 78.8% in Sweden to 4.5% in Romania. Poland ranked in the second position from the very end in this statistic, only surpassing Romania with a 10.9% screening rate [25].

Keeping in perspective the low coverage rates in Poland, observed in August 2023, this study aimed to measure the range and effectiveness of the national HPV vaccination program nearly 1.5 year after its implementation in Poland. Moreover, the study analyzes correlations between the HPV vaccine doses administered and factors, including population size, population shares (urban/rural) coverages, regional variations, and temporal changes associated with the immunization program. The study will provide insight into the low immunization rates, and suggest solutions for both Poland as well as for other countries that have not implemented nationwide vaccination programs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This observational, cross-sectional study analyzed population-based data on the national HPV vaccination program, collected through the National Health Fund (NFZ) and Central Statistical Office (GUS). The data comprised HPV vaccinations (Cervarix® or Gardasil-9®) administered from 2023 to October 2024 in 16 voivodeships (provinces) and the entire country to adolescents in three age groups (11, 12, and 13 years old). The English names of Polish local government units, called voivodeships, are provided in the manuscript, in accordance with the guidelines of the Commission for the Standardization of Geographical Names Outside the Republic of Poland.

Both the NFZ and GUS granted the authors’ request to share the data in accordance with the principles of access to public information. The data obtained was compared with the public state website—report on vaccinations against human papillomavirus (HPV) available at https://ezdrowie.gov.pl/portal/home/badania-i-dane/raport-o-szczepieniach-przeciwko-wirusowi-brodawczaka-ludzkiego-hpv (accessed on 4 August 2025).

HPV vaccination programs in Poland administer a two-dose regimen as part of the vaccination initiative. For the study, a vaccinated individual was considered a patient in a given age group who received at least one dose of HPV vaccination exclusively as part of the program and reported it in their vaccination record (based on the International Classification of Medical Procedures (ICD-9)—code 99.559).

2.2. Statistical Analysis

The statistical significance for all the tests was set at α = 0.05, corresponding to a 5% probability of type I error (false positivity). No data transformations were applied, as variables were continuous and within plausible ranges. Normality was assessed using a Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Since several variables did not meet the assumption of normality, nonparametric methods were applied: Spearman’s rank correlation to assess associations between variables, while group differences were examined using the Kruskal–Wallis test.

3. Results

The results obtained from the analysis were divided into five sections, presented below.

3.1. Relationship Between the Number of Vaccinations and Population Share, and Relationship Between the Number of Vaccinations and Urban Population Shares

At the end of the observation period (October 2024), the level of participation in HPV vaccination, under the population program, was observed to be 8.67%, which is slightly lower than the overall coverage of HPV vaccination in Poland reported by state authorities (9.09%). This result indicates that, regardless of age or the source of financing for the vaccination, inclination for receiving HPV vaccinations remains similar in the Polish society. Poland is divided into sixteen administrative units called voivodships. The level of participation in HPV in voivodships varied from 5.48% to 11.48% (Figure 1).

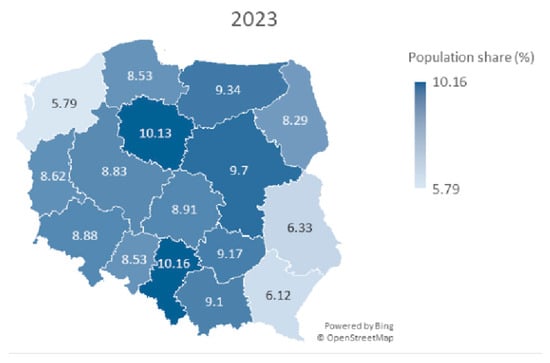

Figure 1.

A map of Poland showing population share (%) of HPV vaccines among children aged 11–13 years for both sexes in particular voivodeships in year 2023.

Sperman’s correlation coefficient was used to check the level of association between the number of vaccinations and the percent of target population share in voivodeships. In 2023, the coefficient was rs = 0.606 (p = 0.013), and in 2024, rs = 0.406 (p = 0.119), indicating a statistically significant, positive correlation in 2023, but not in 2024. In 2023, the greater number of vaccinations was correlated with greater population share in the regions. In 2024, this effect decreased. Furthermore, it implies that higher doses do not necessarily correspond to higher vaccination coverage rates.

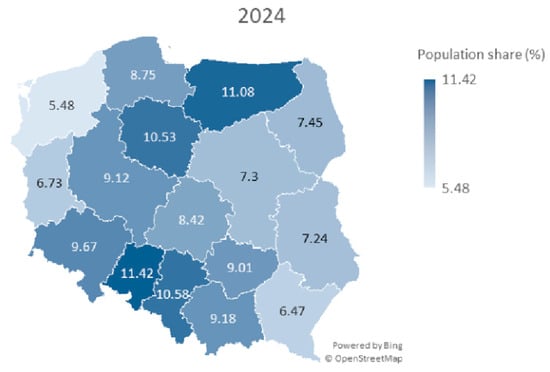

Further analysis considered the correlation between the number of vaccinations in 2023 and 2024 and urban shares for the regions. Spearman’s coefficient was rs = 0.06, p = 0.811, for urban population share. This does not allow us to reject the hypothesis about the lack of correlation between the number of vaccinations and the proportion of the urban population (Table 1). The map of Poland with marked voivodeships and % population coverage with HPV vaccination in selected periods of 2023 and 2024 is shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2. The map shows a pattern in which the eastern part of Poland has lower HPV vaccination coverage.

Table 1.

HPV vaccinations as part of a population program among children aged 11–13 years for both sexes by voivodeship in Poland, June–December 2023 to January–October 2024: population and urban/rural distribution.

Figure 2.

A map of Poland showing population share (%) of HPV vaccines among children aged 11–13 years for both sexes in particular voivodeships in year 2024.

3.2. Correlation Between Population Size and Population Percent Coverage in HPV-Vaccinated Individuals Across 16 Voivodeships in Poland for Three Distinct Age Groups (11–13 Years Old)

The data presented in Table 2 was used to calculate Spearman’s coefficients (and the corresponding t-test for these coefficients), as well as the Kruskal–Wallis test for the variable coverage change. The purpose of applying the Kruskal–Wallis test was to verify the hypothesis that the level of changes did not differ statistically across voivodeships.

Table 2.

Changes in HPV vaccination administration and population dynamics by voivodship and age group in Poland, years 2023–2024 (examined period).

In both 2023 and 2024, the correlation between the variable of interest and the 11-year-old age group was negative but not statistically significant (2023: r = −0.177, p = 0.513; 2024: r = −0.009, p = 0.974). Therefore, there is insufficient evidence to conclude the existence of a meaningful correlation. In both 2023 and 2024, the correlation between the variable of interest and the 12-year-old age group was weak and statistically non-significant (2023: r = 0.025, p = 0.927; 2024: r = 0.294, p = 0.268). Thus, there is no sufficient evidence to support the existence of a meaningful correlation. For the 13-year-old age group, correlations were r =0.233 (p = 0.387) in 2023 and r = 0.256 (p = 0.339) in 2024, indicating negligible, non-significant correlation, indicating no clear relationship between population size and vaccination coverage.

Comparison between both sexes in the age groups of 11, 12, and 13 years old showed no statistically significant correlation between the size of the population at a given age and population coverage/participation in HPV vaccination initiative.

3.3. Relationship Between Changes in Percentage Population and Changes in Population Percentage from 2023 to 2024 for the Same Age Groups

The relationship between population percent changes and population shares percent changes from 2023 to 2024 was assessed using Spearman’s correlation coefficients across the 16 voivodships, stratified by age (Table 2). For the 11-year-old age group, the correlation coefficient was r = 0.027 (p = 0.922), indicating a lack of statistically significant correlation. For the 12-year-old age group, the correlation coefficient was r = −0.358 (p = 0.173), showing no statistically significant correlation. For the 13-year-old age group, the correlation coefficient was r = −0.097 (p = 0.720), reflecting lack of significant correlation.

The flow of people previously vaccinated with one dose to subsequent age groups indicate a non-significant correlation in vaccination coverage, which may mean that a person vaccinated in the previous age group with one dose does not increase interest in starting vaccination of peers in subsequent age groups.

3.4. Analysis of Regional Variations in HPV Vaccination Coverage Changes for the 13-Year-Old Age Group in Poland, 2023–2024

This sub-analysis aimed to determine whether the increase in HPV vaccine doses administered and the population coverage percent change for the 13-year-old age group are equal in proportion across 16 voivodeships in Poland from 2023 to 2024. The average percentage change for Poland in this age group was 37.9% (from 9.7% coverage in 2023 to 13.4% coverage in 2024).

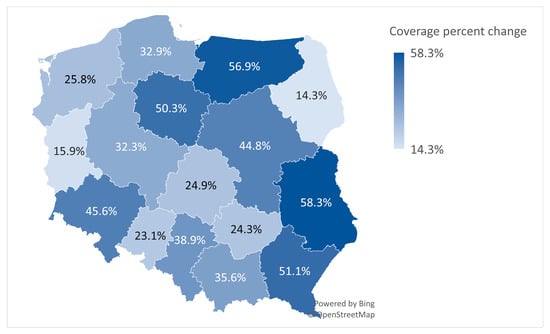

The Lubelskie voivodeship had the greatest increase in population HPV vaccination coverage percent change, with 58.3%, reflecting the largest relative increase in vaccination coverage. The voivodeship with the most diminished (lowest) change was Podlaskie (14.3%), indicating the smallest relative increase in HPV vaccination coverage. Other notable changes include the Warminsko-Mazurskie voivodeship, located in the North-East of Poland (56.9%), which was the second-highest, and Podkarpackie, situated in the South-East (51.1%), the third-highest, while Lubuskie (15.9%) and Opolskie (23.1%) were among the lowest (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The population coverage percent change for the 13-year-old age group.

Analysis with a Kruskal–Wallis test yielded a test statistic of H = 15.0 (df =15, p = 0.45), providing evidence that the population percentage changes do not differ across voivodships (p > 0.05). Given the small sample size (n = 16) and single observation per voivodship, the test’s power is limited and is statistically insignificant.

3.5. Comparison of HPV Vaccination Doses and Coverage by Sex and Age Groups in Poland, 2023–2024

Overall, the findings reveal modest vaccination coverage rates (a maximum of 16.6% in the group of 13-year-old females in 2024), as well as temporal variations between the 2023 and 2024. Females consistently exhibited higher coverage compared to males across all strata. Age-related patterns suggest that coverage tends to increase with advancing age within each year.

Sex gaps persisted (female-to-male ratios 1.35–2.1-fold), and were widest at age 12 in 2023 (15.74% vs. 8.18%) and age 13 in 2024 (16.60% vs. 10.32%), which is attributable to female-centric perceptions of HPV risks despite guidelines for gender-neutral vaccination to mitigate diverse cancers (Table 3).

Table 3.

Summary of product settlement patterns among children aged 11–13 years, stratified by year, age, and sex, for 2023 and 2024.

4. Discussion

This study presents an analysis of the participation of children aged 11–13 in the free-of-charge, nationwide HPV vaccination program in Poland over 1.5 years following its introduction, using data from the NHF-CSO (since June 2023). This is the first assessment of the performance of the vaccination program in Poland. The estimated global vaccination rate coverage of the HPV vaccine remains low (12%). In the World Health Organization (WHO) European Region, the prevalence is approximately 31%. For the “EU-15” countries (this refers to the 15 European Union member states that existed before the major enlargements in 2004), it is correspondingly higher, e.g., Belgium—90%, Great Britain—85%, Denmark—80%, Sweden—80% [26,27]. However, there are developing countries in the world, such as most Arab countries, where public awareness of HPV and vaccination is insufficient and there are no widespread HPV vaccination programs [28,29].

The study demonstrated that there is no evidence that larger populations are associated with higher population coverage with the HPV vaccine. Voivodeships with low population growth or decline tend to experience fewer negative changes in population structure. This suggests that demographic stability can significantly limit the decline in HPV vaccination rates. Voivodeships experiencing population growth or slight decline are more likely to experience milder demographic changes, which may help maintain higher vaccination rates or slow down their decline.

Innovative strategies, such as integrating adolescent HPV vaccination with cervical cancer screening in women aged 30–45, may be beneficial to increase the/vaccination rate and accelerate HPV elimination in Poland. Improving vaccination rates among children and adolescents requires not only easy systemic vaccine access, but it also needs to address parents’ concerns about the safety and effectiveness of the HPV vaccines [26]. An unwillingness to recommend HPV vaccines [30] as well as a dangerous vaccine hesitancy trend have been observed among medical professionals [31,32]. More intensive communication strategies, including school-based education, are necessary to improve parents’ state of knowledge about diseases associated with HPV and promote vaccination decision-making in adolescents. Parental education is another proven factor influencing willingness to vaccinate a child against HPV. The higher the parents’ education level, the larger the vaccination supporters’ group. Improved declared parental knowledge about the risk of HPV infection was found to be associated with greater trust in the physicians and higher willingness to vaccinate the child against HPV [33,34].

In the studied group of adolescents, a lower percentage of vaccinations was represented by the male gender. Unfortunately, the social norms perpetuated over several years, vaccine myths [35], and national policy contributed to the fact that the HPV vaccine is still considered a “feminine” vaccine, associated mainly with girls and women [36]. Daley et al. pointed out that the feminization of the HPV vaccine may negatively impact HPV-related health prophylaxis [37]. Men are also at risk of HPV-related neoplasms; however, this threat is poorly understood among Polish men. A comprehensive educational effort should be implemented to raise awareness among boys and their parents (particularly fathers), to reinforce the belief that HPV vaccination affects them in equal measure to the vaccination of girls and women [38]. Another group that should be the target of educational programs about the risks and routes of HPV infection are the LGBTQ+ community. Adopting a gender-neutral approach to HPV vaccination will reduce the number of HPV infections and diseases transmitted among the population, combat disinformation and fake news, and minimize vaccine-related stigma and promote gender equality [39].

Some studies demonstrate that rural areas are significantly more susceptible to exclusion from healthcare, including vaccinations. This is due to limited access to healthcare services, higher costs associated with traveling to the nearest medical facility, and awareness issues [40]. Despite these obvious arguments, HPV vaccination rates in rural areas may not be significantly lower. In our study, we did not find a significantly higher share of HPV vaccinations in voivodeships with a larger share of urban areas. A survey by Sikora et al. of teens from urban and rural areas in the United States found that rural girls had lower rates of complete HPV vaccination than their urban counterparts [41]. However, reports from 2023 from Vietnam suggest that the overall vaccination rate was 4%, with urban women having a higher rate of 4.9% compared to rural women at 3.1% [42].

Standardized rates of cervical cancer morbidity in Poland (Incidence rates—ESP2013) indicate that, in 2021, the highest incidence was observed in the following voivodeships: Swietokrzyskie (13.3), Warminsko-Mazurskie (12.8), and Pomorskie (12.5). The lowest incidence was observed in the following voivodeships: Podkarpackie (7.7), Malopolskie (8.2), and Lubelskie (8.3). The average for Poland was 10.4 [43].

Interestingly, the Pomorskie Voivodeship has one of the highest HPV vaccination rates for the entire population (within the population program, and outside the program—private funding, for all age groups and genders) at 19.12%, with a national average of 15.92%. Meanwhile, the Podkarpackie Voivodeship, with one of the lowest cervical cancer incidence rates, had the lowest population vaccination rate at 9.8%, using the same criteria.

Further research could focus on patterns of sexual behavior or the incidence of other HPV-related cancers in these voivodeships.

We demonstrated a lower level of coverage with HPV vaccination during the observation period in the eastern regions of Poland, which fits into the broader context of the propensity to vaccinate in Poland. In eastern Poland, the average percentage of children up to 3 years of age who are not vaccinated at all according to the mandatory vaccination schedule is significantly higher, and amounts to 2.12%, with the average in Poland being 1.5% [44].

Despite the efforts and financial outlays on HPV vaccination, the first results of the implementation should be considered far from satisfactory. It is striking that subsequent countries, including Poland, launching vaccination programs do not focus on proven criteria responsible for the success of implementation: awareness and positive attitude of parents towards the HPV vaccination program, mobilization of healthcare professionals, and coordinated strategy [33,45,46].

To improve the effectiveness of national HPV vaccination programs, it seems appropriate to highlight the following recommendations:

- (a)

- Patient interest in publicly funded HPV vaccinations is low in countries without long-standing vaccination awareness. Urgent, widespread outreach efforts should be initiated using social media and involving influencers.

- (b)

- It is expected that vaccination success will not be achieved without the involvement of medical professionals. Training programs for doctors and nurses are needed to develop them as ambassadors for HPV vaccination. Given the shortage of medical staff, an additional financial bonus program “for success” seems essential.

- (c)

- Decision-makers should develop a program to achieve the assumed goal of population coverage with HPV vaccination at three levels: strategic—responsible for creating the mission and vision for the entire process; management—accountable for human resources, IT support, communication model, and corrective actions; and operational—day-to-day implementation of the process.

5. Conclusions

These preliminary results indicate that, after the first 1.5 years of implementing the national HPV vaccination program, its impact is insufficient. Although this is a step in the right direction, the results so far are not promising. The program requires intensive corrective actions. Our research may be valuable for decision-makers in conducting more informative, widely accessible campaigns promoting HPV vaccines—in traditional and social media, where young people are particularly active. Another group that requires a refresher on HPV is physicians. They play a key role in encouraging vaccination, as they encounter patients and their parents during medical visits. The analysis of the initial implementation results we presented may serve as a guide for other countries planning to launch HPV vaccination programs and prevent the same early mistakes from being made in the future. The direction we have presented seems promising, especially in the context of creating a model for an HPV vaccination program that will be resistant to the limitations identified in our study.

6. Study Limitations

The main limitation of this study is the short period spent on the observation and monitoring of vaccinations since the official free-of-charge HPV vaccination program was applied in Poland. The study only considers administered doses of HPV vaccines, not the number of individuals who are completely vaccinated, which, in turn, drives to generalizations and insufficient precision in drawing conclusions based on publicly available data. We were interested in a targeted study at the national level to provide a detailed and independent assessment of immunization uptake based on the available data; however, the study lacks a report on the interest in HPV immunization, as well as data on the implementation of the HPV vaccination program at the national level. We also did not analyze a larger population than just 11–13-year-olds. However, the 11–13-year-old population may be more aware than younger groups and more decisive, being the target population for immunization programs. Further research will focus on the direct causes of low vaccine uptake among the 11–13-year-old population, given the current widespread access to vaccines in Poland.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.P.; methodology, P.P.; data collection, P.P., data analysis, P.P. and M.Ś.; investigation, P.P. and M.Ś.; resources, P.P. and M.Ś.; writing—original draft preparation, P.P., M.Ś., A.R., Y.S., O.M., O.P.-D., and M.D.; writing—review and editing, P.P., M.Ś., O.M., and S.R.K.; visualization, P.P., A.M., and Z.A.; supervision, D.G.W.; project administration, P.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This observational, cross-sectional study used anonymized, secondary population-based data obtained from the National Health Fund (NFZ) and Central Statistical Office (GUS) under public information access principles. No identifiable individual data was included, and no direct contact with participants occurred; thus, formal ethical approval and informed consent were not required.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was waived as the study used publicly available, anonymized secondary data without direct interaction with human subjects.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available as public information at the National Health Fund and the Central Statistical Office, and additionally at https://ezdrowie.gov.pl/portal/home/badania-i-dane/raport-o-szczepieniach-przeciwko-wirusowi-brodawczaka-ludzkiego-hpv (accessed on 4 August 2025).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ewa Wycinka for her assistance in editing the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| HPV | Human papillomavirus |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| HR HPV | High-risk human papillomavirus |

| LR HPV | Low-risk human papillomavirus |

| E6, E7 | Oncoproteins of HPV |

| p53 | Cellular tumor antigen 53; tumor suppressor protein |

| pRB | Retinoblastoma protein; tumor suppressor protein |

| CIN | Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia |

| IARC | International Agency for Research on Cancer |

| EU | European Union |

| NHF | National Health Fund |

| CSO | Central Statistical Office |

| LGBTQ+ | Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer/Questioning, other sexual orientations |

References

- Explaining How Vaccines Work. Vaccines & Immunizations. CDC [Internet]. 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/basics/explaining-how-vaccines-work.html (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Kisling, L.A.; Das, J.M. Prevention Strategies; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023; Updated 1 August 2023. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537222/ (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Cervical Cancer. WHO. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cervical-cancer (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michels, K.B.; zur Hausen, H. HPV vaccine for all. Lancet 2009, 374, 268–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forhan, S.E.; Gottlieb, S.L.; Sternberg, M.R.; Xu, F.; Datta, S.D.; McQuillan, G.M.; Berman, S.M.; Markowitz, L.E. Prevalence of sexually transmitted infections among female adolescents aged 14 to 19 in the United States. Pediatrics 2009, 124, 1505–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sanjosé, S.; Brotons, M.; Pavón, M.A. The natural history of human papillomavirus infection. Best. Pr. Res. Clin. Obs. Gynaecol. 2018, 47, 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, L.; Majerciak, V.; Zheng, Z.M. HPV16 and HPV18 Genome Structure, Expression, and Post-Transcriptional Regulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4943, Erratum in Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7903. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23147903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jentschke, M.; Kampers, J.; Becker, J.; Sibbertsen, P.; Hillemanns, P. Prophylactic HPV vaccination after conization: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccine 2020, 38, 6402–6409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruski, D.; Millert-Kalińska, S.; Łagiedo, M.; Sikora, J.; Jach, R.; Przybylski, M. Effect of HPV Vaccination on Virus Disappearance in Cervical Samples of a Cohort of HPV-Positive Polish Patients. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 7592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Śniadecki, M.; Guani, B.; Jaworek, P.; Klasa-Mazurkiewicz, D.; Mahiou, K.; Mosakowska, K.; Buda, A.; Poniewierza, P.; Piątek, O.; Crestani, A.; et al. Tertiary prevention strategies for micrometastatic lymph node cervical cancer: A systematic review and a prototype of an adapted model of care. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2024, 197, 104329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Human Papillomavirus and Related Cancers, Fact Sheet. 2023. Available online: https://hpvcentre.net/statistics/reports/POL_FS.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Fashedemi, O.; Ozoemena, O.C.; Peteni, S.; Haruna, A.B.; Shai, L.J.J.; Chen, A.; Rawson, F.J.; Cruickshank, M.E.; Grant, D.M.; Ola, O.; et al. Advances in human papillomavirus detection for cervical cancer screening and diagnosis: Challenges of conventional methods and opportunities for emergent tools. Anal. Methods 2025, 17, 1428–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murewanhema, G.; Moyo, E.; Dzobo, M.; Mandishora-Dube, R.S.; Dzinamarira, T. Human papilloma virus vaccination in the resource-limited settings of sub-Saharan Africa: Challenges and recommendations. Vaccine X 2024, 20, 100549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutz, J.M.; Rausche, P.; Gheit, T.; Puradiredja, D.I.; Fusco, D. Barriers and facilitators of HPV vaccination in sub-saharan Africa: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, H.J.; Wilson, R.; Hanley, S.; Parys, A.; Paterson, P. Tracking the global spread of vaccine sentiment: Global response to Japan’s suspension of HPV vaccination recommendations. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2014, 10, 2543–2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnabas, R.V.; Brown, E.R.; Onono, M.; Bukusi, E.A.; Njoroge, B.; Winer, R.L.; Donnell, D.; Galloway, D.; Cherne, S.; Heller, K.; et al. Effectiveness of single-dose HPV vaccination among adolescent girls and young women in Kenya (KEN SHE study): Randomized controlled trial protocol. Trials 2021, 22, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudo, R.; Yamaguchi, M.; Peteni, S.; Adachi, S.; Ueda, Y.; Miyagi, E.; Hara, M.; Hanley, S.J.B.; Enomoto, T. Bivalent Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Effectiveness in a Japanese Population: High Vaccine-Type-Specific Effectiveness and Evidence of Cross-Protection. J. Infect. Dis. 2019, 219, 382–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukács, A.; Máté, Z.; Farkas, N.; Mikó, A.; Tenk, J.; Hegyi, P.; Németh, B.; Czumbel, L.M.; Wuttapon, S.; Kiss, I.; et al. The quadrivalent HPV vaccine is protective against genital warts: A meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, J.; Ploner, A.; Elfström, K.M.; Wang, J.; Roth, A.; Fang, F.; Sundström, K.; Dillner, J.; Sparén, P. HPV Vaccination and the Risk of Invasive Cervical Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1340–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kjaer, S.K.; Dehlendorff, C.; Belmonte, F.; Baandrup, L. Real-World Effectiveness of Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Against Cervical Cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2021, 113, 1329–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polish Ministry of Health. Recommendations of the Minister of Health Regarding the Implementation of Vaccinations Against Human Papillomavirus (HPV) as Part of the Universal Vaccination Program. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/attachment/a7795344-3096-464e-8a22-beea93d06a75 (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Michalek, I.M.; Koczkodaj, P.; Didkowska, J. National launch of human papillomavirus (HPV) immunization program in Poland, 2023. Vaccine X 2024, 17, 100436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institute of Public Health - National Institute of Hygiene. What Does the Implementation of the HPV Vaccination Program Look Like After 2.5 Months of Its Implementation? Available online: https://szczepienia.pzh.gov.pl/jak-wyglada-realizacja-programu-szczepien-przeciw-hpv-po-25-miesiacach-jego-realizacji/ (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Cancer Screening Statistics. Eurostat [Internet]. 2024. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Cancer_screening_statistics (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Nowakowski, A.; Prusaczyk, A.; Szenborn, L.; Ludwikowska, K.; Paradowska-Stankiewicz, I.; Machalek, D.A.; Baay, M.; Burdier, F.R.; Waheed, D.E.; Vorsters, A. The HPV prevention and control program in Poland: Progress and the way forward. Acta. Dermatovenerol. Alp. Pannonica Adriat. 2024, 33, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borowska, M.; Koczkodaj, P.; Mańczuk, M. HPV vaccination coverage in the European Region. Nowotw. J. Oncol. 2024, 74, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsous, M.M.; Ali, A.A.; Al-Azzam, S.I.; Abdel Jalil, M.H.; Al-Obaidi, H.J.; Al-Abbadi, E.I.; Hussain, Z.K.; Jirjees, F.J. Knowledge and awareness about human papillomavirus infection and its vaccination among women in Arab communities. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bencherit, D.; Kidar, R.; Otmani, S.; Sallam, M.; Samara, K.; Barqawi, H.J.; Lounis, M. Knowledge and Awareness of Algerian Students about Cervical Cancer, HPV and HPV Vaccines: A Cross-Sectional Study. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sypień, P.; Marek, W.; Zielonka, T.M. Awareness and Attitude of Polish Gynecologists and General Practitioners towards Human Papillomavirus Vaccinations. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, M.; Coppeta, L.; Olesen, O.F. Vaccine Hesitancy among Healthcare Workers in Europe: A Systematic Review. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaghan, T.; Washburn, D.; Goidel, K.; Nuzhath, T.; Spiegelman, A.; Scobee, J.; Moghtaderi, A.; Motta, M. Imperfect messengers? An analysis of vaccine confidence among primary care physicians. Vaccine 2022, 40, 2588–2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, C.; Stoney, T.; Hutton, H.; Parrella, A.; Kang, M.; Macartney, K.; Leask, J.; McCaffery, K.; Zimet, G.; Brotherton, J.M.; et al. School-based HPV vaccination positively impacts parents’ attitudes toward adolescent vaccination. Vaccine 2021, 39, 4190–4198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobierajski, T.; Małecka, I.; Augustynowicz, E. Feminized vaccine? Parents’ attitudes toward HPV vaccination of adolescents in Poland: A representative study. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2023, 19, 2186105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taumberger, N.; Joura, E.A.; Arbyn, M.; Kyrgiou, M.; Sehouli, J.; Gultekin, M. Myths and fake messages about human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination: Answers from the ESGO Prevention Committee. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2022, 32, 1316–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, K.A.; Vivian, E.; Loux, T.M.; Arnold, L.D. Factors Associated With Parents’ Intent to Vaccinate Adolescents for Human Papillomavirus: Findings From the 2014 National Immunization Survey-Teen. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2017, 14, E45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daley, E.M.; Vamos, C.A.; Thompson, E.L.; Zimet, G.D.; Rosberger, Z.; Merrell, L.; Kline, N.S. The feminization of HPV: How science, politics, economics and gender norms shaped U.S. HPV vaccine implementation. Papillomavirus Res. 2017, 3, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reszka, K.; Moskal, Ł.; Remiorz, A.; Walas, A.; Szewczyk, K.; Staszek-Szewczyk, U. Should men be exempted from vaccination against human papillomavirus? Health disparities regarding HPV: The example of sexual minorities in Poland. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2021, 62, E386–E391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dykens, J.A.; Peterson, C.E.; Holt, H.K.; Harper, D.M. Gender neutral HPV vaccination programs: Reconsidering policies to expand cancer prevention globally. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1067299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, H.M.; Vanderpool, R.C.; Pilar, M.; Zubizarreta, M.; Stradtman, L.R. A narrative review of HPV vaccination interventions in rural U.S. communities. Prev. Med. 2021, 145, 106407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swiecki-Sikora, A.L.; Henry, K.A.; Kepka, D. HPV Vaccination Coverage Among US Teens Across the Rural-Urban Continuum. J. Rural. Health 2019, 35, 506–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, N.T.; Phan, T.N.T.; Pham, T.T.; Le, T.T.; Le, H.M.; Nguyen, D.T.; Lam, A.N.; Pham, T.T.; Le, H.T.; Dang, N.B.; et al. Urban-rural disparities in acceptance of human papillomavirus vaccination among women in Can Tho, Vietnam. Ann. Ig. Med. Prev. Comunità 2023, 35, 641–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didkowska, J.; Barańska, K.; Miklewska, M.J.; Wojciechowska, U. Cancer incidence and mortality in Poland in 2023. Nowotw. J. Oncol. 2024, 74, 75–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaccinations in Poland in 2024. Available online: https://wwwold.pzh.gov.pl/oldpage/epimeld/2024/Sz_2024.pdf (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Efua Sackey, M.; Markey, K.; Grealish, A. Healthcare professional’s promotional strategies in improving Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination uptake in adolescents: A systematic review. Vaccine 2022, 40, 2656–2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aggarwal, S.; Agarwal, P.; Gupta, N. A comprehensive narrative review of challenges and facilitators in the implementation of various HPV vaccination program worldwide. Cancer Med. 2024, 13, e6862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).